Abstract

Summary: In this report, we describe an unusual case of chondrosarcoma that involved the entire bimaxillary and nasal skeleton. The pathogenesis, correlation of histopathology with radiology, and management of chondrosarcoma are reviewed.

Chondrosarcoma is an uncommon malignant neoplasm of cartilaginous origin; fewer than 10% of all cases of chondrosarcoma occur in the craniofacial region (1), making craniofacial chondrosarcoma a rare disease entity. Chondrosarcoma of the craniofacial region may arise from any bone, cartilaginous, or soft-tissue structures but most commonly involves the mandible, maxilla, or cervical vertebrae (2). In this report, we present a case of chondrosarcoma, probably originating in the nasal septum, with bilateral extension into the ethmoid sinuses as well as the right and left maxillary sinuses. Although unusual in its extensive local involvement, the case is illustrative in its clinical, radiologic, and histologic presentation.

Case Report

A 32-year-old homeless man with a history of alcohol and drug abuse was seen at an outside hospital for symptoms related to depression. He reported a 3–4-year history of nasal congestion. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The results of a physical examination were notable for a tissue mass obstructing both nostrils. The patient’s sense of smell was also diminished bilaterally. MR imaging and CT scanning were performed to assess the nasal mass. MR imaging showed a heterogeneously enhancing mass centered at the nasal septum, extending into the ethmoid sinuses, both the right and left maxilla, and the maxillary sinuses bilaterally. Erosion into multiple sinus walls as well as the right orbital floor was present. The mass also extended inferiorly, causing bowing of the right hard palate (Fig 1A–C). The tumor did not erode into the cribriform plate, as evidenced by the bone window coronal CT scan (Fig 1D and E). Areas of curvilinear calcifications and ossifications were noted within the mass. Biopsy of the mass showed histologic findings consistent with chondrosarcoma. The patient underwent resection of right and left maxillary sinuses, the nasal bones, and the ethmoid sinuses.

Fig 1.

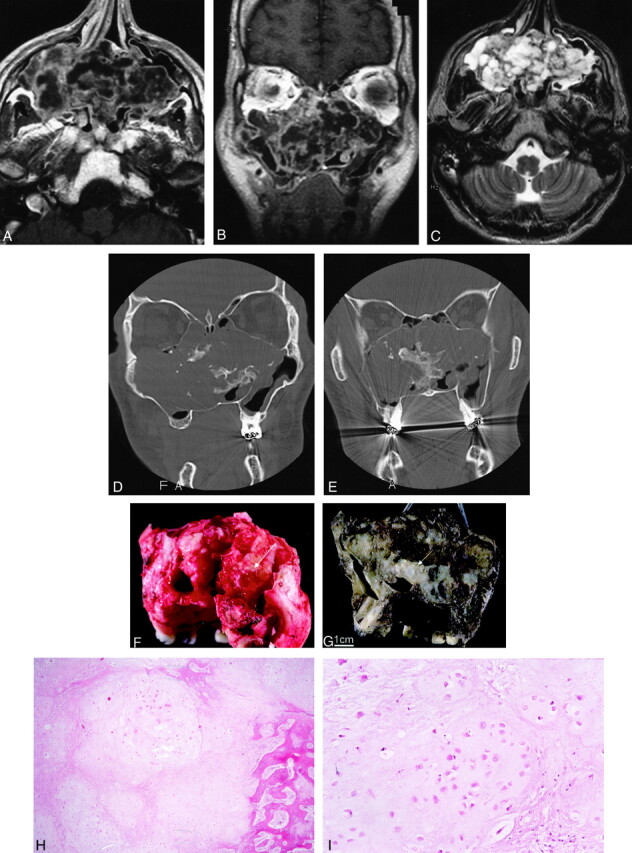

Images from the case of a 32-year-old man with chondrosarcoma involving bilateral ethmoid and maxillary sinuses.

A and B, Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images (600/15/2 [TR/TE/NEX]; section thickness, 5 mm) show a large, heterogeneously enhancing mass centered at the nasal septum, involving the ethmoid sinuses and maxillary sinuses.← The mass extends into the inferior right orbit without infiltration of the rectus muscles or intraconal structures. No evidence of dural enhancement to suggest intracranial extension is present.

C, Axial T2-weighted MR image (4000/102/2; section thickness, 5 mm) shows a heterogeneous mass, as seen before, with low-signal-intensity septation.

D and E, Bone window coronal CT scans show a large lobulated mass with a calcified and chondroid matrix extending into the maxillary and the ethmoid sinuses. There is destruction of the sinus wall and the right orbital floor. D shows that the mass extends inferiorly, causing bowing of the right side of the hard palate. E demonstrates that the mass does not extend intracranially because no evidence of erosion into the cribriform plate is visible. Image in E is more posterior than image in D.

F, Bilateral maxillectomy specimen shows a tan-pink, lobulated tumor mass (6 × 4 × 4 cm) that fills the bilateral maxillary sinuses and is present at the superior (orbital) and posterior margins (arrow, not a final surgical margin). The tumor was hard to waxy, with numerous calcifications.

G, Bilateral maxillectomy specimen after decalcification shows tumor in the right maxillary sinus, extending across the nasal cavity (arrow) and into the left maxillary sinus.

H, At low power, the tumor is composed of lobules of pale-staining chondroid matrix. Infiltration of the bone is seen at the right side of the field (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification ×200).

I, At higher power, the tumor resembles normal cartilage. Chondrocytes reside within lacunae in a pale-staining amorphous matrix. Compared with benign cartilage or enchondroma, however, the tumor is more cellular. Cell nuclei tend to be larger and more irregular, and binucleation within a single lacuna is more common.

After bilateral maxillectomy, the resection specimen showed a large tan-pink lobulated tumor mass (6 × 4 × 4 cm) filling the bilateral maxillary sinuses. The tumor was hard, with numerous calcifications. After decalcification, the specimen was sagittally sectioned to reveal tumor destruction of the medial maxillary walls and extension across the nasal cavity to both maxillary sinuses. Tumor was present extensively at the posterior margin and was focally invading the floor of the right orbit (Fig 1F and G). Additional resection was performed to achieve clean margins.

Microscopic examination revealed that the tumor was composed of lobules of pale-staining chondroid matrix that both infiltrated the preexisting bone and focally caused bone destruction. The chondrocytes resided within lacunae in the matrix. Compared with benign cartilage or enchondromas, the nuclei seen here were larger and more irregular. Binucleation within a single lacuna was also more common, and the overall cellularity was higher (Fig 1H and I). This tumor was designated low to intermediate grade.

Discussion

Chondrosarcomas are a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors derived from a cartilaginous origin. Although most chondrosarcoma tumors arise from cartilaginous or bone structures, they may also develop in soft tissues, in which cartilage is normally not found (3). It is unclear whether the latter tumors develop from mesenchymal differentiation or ectopic chondroid precursor cells. They account for approximately 11–25% of all primary sarcoma tumors of the bone and are most commonly found in the long bones and the pelvis. Less than 10% of all cases of chondrosarcoma involve the craniofacial region, accounting for <2% of all head and neck tumors (3).

The presenting symptom of the case discussed herein was characteristic of craniofacial chondrosarcoma. This type of tumor is most commonly a painless mass that progresses to symptomatic complaints, such as impaired vision, nasal obstruction, and dental abnormalities. In rarer instances, it may also present with swelling of the cheek, headaches, dysphagia, and sensory alterations in the neck, shoulder, and arm (2).

In part due to the rarity of chondrosarcomas, their epidemiologic risk factors remain poorly defined. The male-female ratio is approximately 1.2:1 (2). Most chondrosarcoma tumors occur in patients younger than 40 years. They have been reported to develop in association with malignant conditions, such as osteosarcoma, melanoma, fibrosarcoma, and leukemia, as well as benign conditions, such as Paget disease and fibrous dysplasia (1–3). Additionally, data derived from the National Cancer Database show a slightly higher prevalence of head and neck chondrosarcoma tumors in patients of lower income (3). The presented case had no significant medical history but is the case of a 32-year-old homeless man.

Recent studies suggest that the pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma may involve mutational inactivation of previously identified tumor suppressor genes. Mutational inactivation of the p16, Rb, and p53 tumor suppressor genes in chondrosarcoma samples has been reported (4–6). Moreover, p53 inactivation is associated with higher grade tumors as well as poorer prognosis (6). Because both chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma are associated with Rb and p53 mutations (6, 7), the association between these two diseases may reflect common mutational events. Loss of heterozygosity in other DNA regions bearing putative tumor suppressor genes has also been implicated in chondrosarcoma pathogenesis (8).

The radiologic appearance of the case presented herein is highly suggestive of chondrosarcoma. On CT scans, chondrosarcoma appears as a lobulated mass containing an irregular chondroid matrix with bone invasion and destruction. The signal density of the chondroid matrix is lower than that of the bone matrix, although regions of bone density may be observed because of localized ossification. With T1-weighted imaging, the administration of contrast material results in curvilinear septa enhancement of the fibrovascular tissues within chondrosarcoma tumors. The nonenhanced areas consist mostly of cartilages, mucoid tissues, or necrosis. The chondroid matrix is bright on T2-weighted images because of higher water content, whereas the ossified regions appear dark (9).

The extent of tumor spread in this patient is unusual. The symmetric appearance of the tumor centering on the septal region suggests nasal septum as the site of origin. Although metastatic chondrosarcoma is a formal possibility, it is unlikely considering the location of the presenting tumor and the absence of other symptoms and physical findings in the patient. Squamous cell carcinoma can also occur in this region, although it is not known to contain calcified or ossified components. Because of the extensive sensory innervation of the nasal cavity, most septal tumors are detected before such widespread involvement. The extent of local spread in this patient is likely secondary to neglect.

Delineation of chondrosarcoma boundary relative to normal tissue can be achieved with >98% accuracy when combining CT and MR imaging modalities (10). Although MR imaging offers better soft-tissue visualization, thereby allowing differentiation of tumor from surrounding tissues or edema, CT is superior in revealing bone erosion, particularly in the region of the cribriform plate, orbit, pterygopalatine fossae, and infratemporal fossae. Intracranial extension can also be detected as dural enhancement subsequent to the administration of contrast material. Additionally, MR imaging is the best modality for monitoring tumor recurrence (10). Most cases of chondrosarcoma are hypovascular and do not require delineation of vascular anatomy by angiography (11). Distant metastasis is rare in association with chondrosarcoma and most often involves the lung (2). Therefore, bone scans play limited roles in the management of chondrosarcoma.

Surgery is the mainstay treatment for patients with chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Because chondrosarcoma generally does not show mitotic activity, grading is based on cellularity and nuclear enlargement and irregularity with scores of 1, 2, and 3 (low, intermediate, and high grades, respectively). The prognosis is generally good for low and intermediate grade chondrosarcoma (12). Tumor involvement at the resection margin is the only other poor prognostic sign (2). The overall 5-year disease-free survival for low-grade chondrosarcoma after complete resection ranges between 54–77% (1–3). The most common cause of death is recurrence with local invasion of the skull base (2). Regarding the prognostic factors, the chondrosarcoma presented herein was designated low to intermediate grade and was completely resected. The patient’s prognosis is, therefore, excellent. The patient has been free of disease for the last 3 years and continues to undergo close follow-up examination.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Foundation for Surgical Research and Education.

References

- 1.Gadwal SR, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gannon FH, Thompson LD. Primary chondrosarcoma of the head and neck in pediatric patients: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with a review of the literature. Cancer 2000;88:2181–2188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruark DS, Schlehaider UK, Shah JP. Chondrosarcomas of the head and neck. World J Surg 1992;16:1010–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch BB, Karnell LH, Hoffman HT, et al. National cancer database report on chondrosarcoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2000;22:408–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asp J, Sangiorgi L, Inerot SE, et al. Changes in p16 gene but not the p53 gene in human chondrosarcoma tissues. Int J Cancer 2000;85:782–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenberg MB, Woloschak M, Sen C, Wolfe D. Loss of heterozygosity in the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor in skull base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. Surg Neurol 1997;47:160–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshiro Y, Chaturvedi V, Hayden D, et al. Altered p53 is associated with aggressive behavior of chondrosarcoma: a long term follow-up study. Cancer 1998;83:2324–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs N, Winkler K. Osteosarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol 1993;5:667–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bovee JV, Cleton-Jansen AM, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn NJ, et al. Loss of heterozygosity and DNA ploidy point to a diverging genetic mechanism in the origin of peripheral and central chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1999;26:237–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geirnaerdt MJ, Bloem JL, Eulderink F, Hogendoorn PC, Taminiau AH. Cartilaginous tumors: correlation of gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging and histopathologic findings. Radiology 1993;186:813–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd G, Lund, VJ, Howard D, Savy, L. Optimum imaging for sinonasal malignancy. J Laryngol Otol 2000;114:988–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korten AG, ter Berg HJ, Spincemaille GH, van der Laan RT, Van de Wel AM. Intracranial chondrosarcoma: review of the literature and report of 15 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:88–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pritchard DJ, Lunke RJ, Taylor WF, Dahlin DC, Medley BE. Chondrosarcoma: a cliniopathologic and statistical analysis. Cancer 1980;45:149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]