Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Evaluation of images of perineural tumor spread in patients with head and neck malignancies is essential for planning treatment and determining the patient’s prognosis. Although the communications between the facial and trigeminal nerves are not widely known, they may provide a route for tumor growth. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the course of the auriculotemporal nerve, as well as the clinical and imaging findings that suggest involvement of the communication between the facial nerve and the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve.

METHODS: Images in 15 patients with clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve were reviewed. Involvement of the main trunk of the facial nerve, auriculotemporal nerve, V3, trigeminal cistern, and ganglion and adjacent anatomic structures were noted in each patient.

RESULTS: The course of the auriculotemporal nerve was described in detail. More than 50% of patients with perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve had clinical signs of auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction, including periauricular pain and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction or tenderness. Images in 13 of 15 patients with such tumor spread demonstrated findings of tumor growth along V3..

CONCLUSION: Knowledge of the course of the auriculotemporal nerve is critical in evaluating images for findings of tumor spread along this nerve. Periauricular pain, TMJ dysfunction or tenderness, and imaging signs of V3 involvement are important indicators of potential involvement of the auriculotemporal nerve.

Infiltrating carcinomas of the head and neck region may disseminate along nerves and lead to a circumstance that may create a poor prognosis and require aggressive treatment (1). Perineural tumor spread may cause local and referred pain or dysesthesias that can appear before or when the primary tumor is discovered or years after initial therapy. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the minor and major salivary glands is well known for its tendency to cause perineural tumor growth at presentation. However, in the large percentage of patients with perineural tumor spread in the head and neck region, it arises from primary squamous cell carcinomas of cutaneous origin. The facial nerve and the maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3) divisions of the trigeminal nerve are the nerves most commonly affected by perineural tumor growth (2). The appearance of perineural tumor spread, including thickening and abnormal enhancement or both along the main branches of these nerves, foraminal widening, and erosions or obliteration or both of the perineural fat pads, has been well described in the radiologic literature (2–4).

Recent publications (5–8) emphasize the perineural dissemination of tumor along preexistent communications between the facial and trigeminal nerves. Despite the presence of multiple potential anatomic communications between these two nerves, only perineural tumor spread along the greater superficial petrosal nerve, as well as the vidian nerve, and tumor growth into the pterygopalatine fossa have been reported so far.

This study focused on the auriculotemporal nerve as a possible route of perineural dissemination between the facial nerve and V3. Usually, the auriculotemporal nerve is not visualized on cross-sectional images. Lack of knowledge of its existence and course may prevent the detection of possible perineural tumor growth at a potentially curable stage. The anatomy of the auriculotemporal nerve was reviewed, and multiple examples of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve were assessed on cross-sectional images.

Methods

Since 1986, 13 patients with clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve were examined at our institution, and the cross-sectional images obtained at outside institutions in two additional patients were assessed. Therefore, our patients included 14 men and one woman. Their age range was 33–79 years, and their mean age was 61.5 years. Eleven of the 15 patients underwent CT and MR imaging, one underwent only MR imaging, and three underwent only CT. All studies, but one CT study, were performed after the administration of contrast material. Five of the 15 patients had a parotid gland tumor with the following pathologic types: adenoid cystic carcinomas (n = 2), adenocarcinoma (n = 1), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 1), and metastatic undifferentiated carcinoma of unknown primary site combined with lymphoma (n = 1). Of the remaining 10 patients, seven had metastatic squamous cell carcinoma caused by primary skin cancer in the head and neck region, one had a malignant schwannoma, one had a neurofibroma, and one had a tumor of unknown pathologic origin.

Two radiologists (A.A.M., I.M.S.) evaluated the images, focusing on the following: 1) involvement of the main trunk of the facial nerve; 2) involvement of the auriculotemporal nerve; 3) involvement of the trigeminal nerve (the involved division of the trigeminal nerve was recorded); 4) skull base erosion; 5) intracranial extension, including extension to the trigeminal cistern rootlets and trigeminal ganglion; and 6) involvement of other anatomic structures, such as the middle meningeal artery in the infratemporal fossa (medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, mandibular ramus, fat pad medial to the mandibular ramus, fat pad between the pterygoid muscles).

Perineural tumor spread was defined as enlargement or abnormal enhancement of the evaluated nerves or obliteration of the perineural fat pad or both. The imaging findings were correlated with clinical symptoms, particularly the presence of facial nerve palsy, numbness in the trigeminal nerve distribution, and symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction, which occurred subsequently. Additionally, failure to observe such spread on these images at the time of original interpretation was noted, and the resultant delay in treatment was recorded (in terms of months).

Results

The cross-sectional images in 14 of 15 patients depicted definitive signs of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve. In the remaining subject, perineural tumor growth along the lateral aspect of the auriculotemporal nerve was suggested on CT scans.

Surgically and Pathologically Proven Cases

Positive findings of perineural tumor spread at pathologic analysis.—

In seven of the 15 patients, the radiographically diagnosed perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve was confirmed at surgery. Four of these seven patients (patients 1–3 and 5 in Table 1) had symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve involvement including otalgia (one patient) and periauricular pain (three patients). The remaining three (patients 4, 6, and 7 in Table 1) were asymptomatic in this regard.

TABLE 1:

Patients with pathologically proven perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve

| Patient No. | Diagnosis | Cranial Nerve Palsy | Symptoms | Involvement |

Additional Imaging Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial Nerve Main Trunk | Auriculotemporal Nerve | Cranial Nerve V | Skull Base | Intracranial | |||||

| 1 | Poorly differentiated adenoid cystic carcinoma | VII palsy at presentation, V3 palsy 10 mo later | Otalgia | Yes | Yes | Suspected | No | No | None |

| 2 | Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma | VII palsy at presentation | Face swelling, preauricular pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | None |

| 3 | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | VII palsy for 2 y, pain in V3 distribution for 1 y | Periauricular pain for 1 y | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | None |

| 4 | Unknown | Right VII palsy at presentation | Preauricular swelling | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Involvement of infratemporal fossa |

| 5 | Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma | VII palsy at presentation | Preauricular pain and swelling | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, 16 mo after initial diagnosis | Yes, 16 mo after initial diagnosis | Involvement of infratemporal fossa |

| 6 | Malignant schwannoma | VII palsy at presentation, V2 palsy for 16 y | Intermittent diplopia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Involvement of V2 |

| 7 | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | VII palsy at presentation | Mass posterior to left jaw | No | Yes | No | No | No | None |

In five of these seven patients, definite extension of the tumor along V3 was seen on cross-sectional images. In one of these five patients (patient 6 in Table 1), the trigeminal ganglion and cistern, as well as V2, also were involved.

In one other patient (patient 1 in Table 1), V3 had subtle enhancement on images; therefore, tumor growth along this branch was suspected. Since the patient had clinical signs of cranial nerve palsy involving V3, this finding was thought to be true. The patient was treated with external radiation therapy after surgical resection. This patient did not have cross-sectional findings of intracranial involvement, skull base erosion, or involvement of other anatomic structures at the time of diagnosis; such findings did develop during the year for which follow-up studies were available.

The remaining patient (patient 7 in Table 1) did not have symptoms related to the auriculotemporal or trigeminal nerve. The cross-sectional studies indicated the presence of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve that originated from a mass in the deep lobe of the parotid gland and revealed no signs of involvement of V3 or the main trunk of the facial nerve, of skull base erosion, of intracranial invasion, or of involvement of other adjacent anatomic structures (Fig 1). This patient underwent complete surgical resection of the tumor, and the pathologic evaluation revealed mucoepidermoid carcinoma, with signs of perineural invasion along the auriculotemporal nerve. This patient also underwent postsurgical radiation therapy to the surgical bed and ipsilateral neck. At the last follow-up, performed 35 months after parotidectomy, the patient was alive and did not have signs of disease.

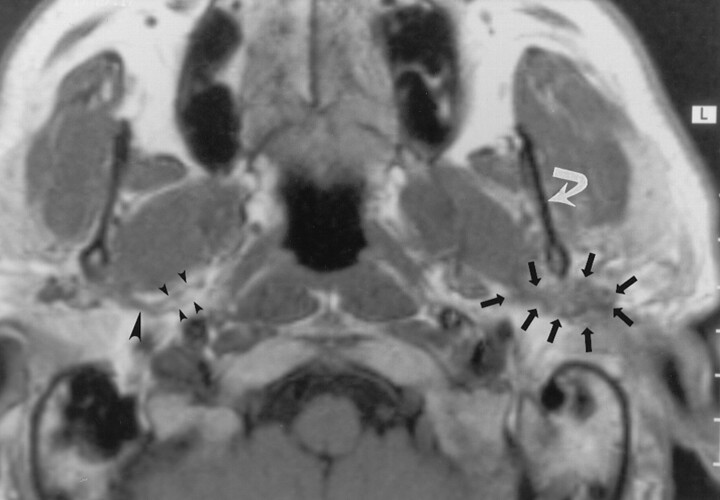

Fig 1.

Axial nonenhanced T1-weighted MR image (700/10 [TR/TE]) obtained in a 50-year-old man with mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland, a mass posterior to the left mandible, and no symptoms of TMJ dysfunction or neurologic signs related to V3 or the facial nerve. The image demonstrates a soft-tissue mass (straight arrows) posterior to the left mandibular ramus (curved arrow) that extends along the expected course of the left auriculotemporal nerve. MR examination revealed no signs of V3 or facial nerve involvement. These findings were interpreted as suggesting isolated perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve; this was confirmed at pathologic examination. Note the normal appearance of the auriculotemporal nerve on the right side, with its two rootlets (small arrowheads) and trunk (large arrowhead).

Six of the seven patients (all but patient 7 in Table 1) had imaging findings of perineural tumor spread along the facial nerve main trunk. These were confirmed during surgery and pathologic analysis. In two patients, tumor also invaded the masticator space (patients 4 and 5 in Table 1) (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

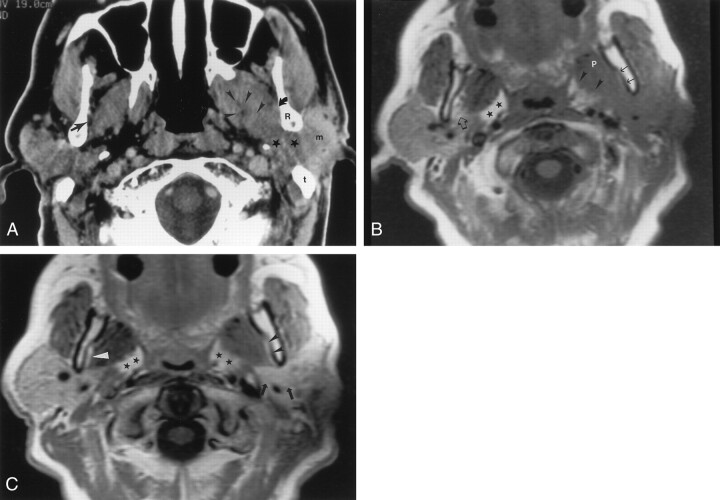

Axial images obtained in a 55-year-old man with squamous cell carcinoma of the left temporal region, who had pain and swelling in the preauricular region, as well as facial nerve weakness.

A, Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows an infiltrating mass (m) in the left parotid gland that extends medially (★) between the ramus of the mandible (R) and mastoid tip (t) into the parapharyngeal space, along the expected course of the auriculotemporal nerve. Note the asymmetry in the parapharyngeal fat plane when compared with the right side. The tumor extends within the parapharyngeal space (arrowheads) anteriorly and superiorly to involve V3 (not shown). In addition, the tumor extends along the medial margin of the mandibular ramus to infiltrate the masticator space (curved arrow). Note the preserved fat plane (straight arrow) on the right side. The scan does not show the degree of invasion of the lateral pteryoid muscle.

B, Nonenhanced T1-weighted MR image (500/11) shows the same findings as in A at a slightly lower level. Note the differences in signal intensity in the parapharyngeal fat planes (★). The left parapharyngeal fat plane has slightly lower signal intensity than that of the right; this is a sign of tumor involvement (arrowheads). The fat plane medial to the ramus of the mandible on the left is completely obliterated (solid arrows), compared with that of the right (open arrow); this is a sign of tumor extension into the masticator space. Also note the slightly increased signal intensity of the lateral pterygoid muscle (P), compared with that of the right; this is consistent with involvement by tumor.

C, Contrast-agent–enhanced T1-weighted MR image (500/11) obtained with same parameters and at the same level as in B shows no substantial asymmetry in the retromandibular regions (arrows) and parapharyngeal spaces (★). The fat plane medial to the ramus of the mandible (black arrowheads) seems to be intact, when compared with that on the right (white arrowhead). Without the nonenhanced T1-weighted MR images, the full extent of the tumor would have been undiagnosed.

The results are summarized in Table 1.

Negative findings of perineural tumor spread at pathologic evaluation.—

In the one patient with CT findings suggestive of tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve, no signs of perineural tumor spread along this nerve were seen during surgery or pathologic evaluation (Fig 3). The CT scan in this patient demonstrated a parotid gland tumor located predominantly in the superficial lobe of the parotid gland and extending to the region of the facial nerve main trunk and retromandibular area. No signs of involvement of the trigeminal nerve, skull base erosions, or invasion of the cavernous sinus were present. On the CT scan, distinction of the primary parotid tumor and possible additional tumor growth along a lateral portion of the auriculotemporal nerve was difficult. Therefore, MR imaging was recommended for further evaluation, but it was not performed. Clinically, this patient had subjective facial nerve weakness that could not be confirmed at physical examination. This patient also had no symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction. At the last follow-up examination performed 9 months after surgical resection and postsurgical radiation therapy to the parotid gland region and anterior neck, this patient was alive and free of disease. The finding was considered to be falsely positive.

Fig 3.

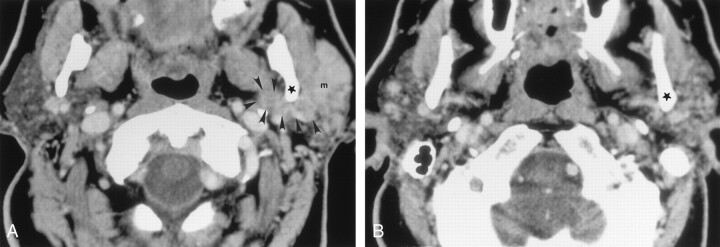

Axial contrast-agent–enhanced CT images obtained at two levels in a 77-year-old man with metastatic undifferentiated carcinoma and lymphoma who had a left facial mass and facial weakness.

A, Scan shows that a homogeneous soft-tissue mass (m), which extends medially (arrowheads) along the posterior margin of the ramus (★) of the mandible, almost completely replaces the left parotid gland. This finding was interpreted as suggesting perineural tumor spread along the facial nerve main trunk and auriculotemporal nerve. Pathologic findings, however, did not confirm this. Retrospective review of the CT scans revealed that the soft-tissue mass actually was lower than the expected course of the auriculotemporal nerve.

B, Scan illustrates the correct level of the auriculotemporal nerve. No abnormality in the retromandibular region is depicted at this level. ★ indicates the posterior margin of the mandibular ramus.

Surgically and Pathologically Unproven Cases

Seven of the 15 patients with cross-sectional findings of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve did not undergo surgical resection at all or underwent only resection of the parotid mass. Therefore, no pathologic analysis of the nerves was performed.

Five of these seven patients (patients 3–7 in Table 2) had symptoms related to the auriculotemporal nerve, including periauricular pain (four patients), ear discomfort (one patient), otalgia (one patient), or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) tenderness (one patient) or dysfunction (one patient). The remaining two patients (patients 1 and 2 in Table 2) were asymptomatic in this regard.

TABLE 2:

Patients perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve, as determined with imaging findings

| Patient No. | Diagnosis | Cranial Nerve Palsy | Symptoms | Involvement |

Additional Imaging Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial Nerve Main Trunk | Auriculotemporal Nerve | Cranial Nerve V | Skull Base | Intracranial | |||||

| 1 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | VII palsy at presentation | Facial weakness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Temporal bone along the facial canal | No | None |

| 2 | Squamous cell carcinoma | VII palsy at presentation, V3 3 mo later | Pretragal mass | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes, 7 m after initial diagnosis | None |

| 3 | Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma | Clinically suspected auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction, V3 palsy 10 mo later | Ear discomfort, TMJ tenderness | Yes | Yes | Yes | At the foramen spinosum and ovale | No | Spread along the middle meningeal artery |

| 4 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | VII and V palsy, clinically suspected auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction | Retromandibular and pretragal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | At the right foramen ovale | Yes, 14 mo after initial diagnosis | Involvement of infratemporal fossa |

| 5 | Neurofibroma | V3 palsy at presentation | Pain and mass in the right mandibular region | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | None |

| 6 | Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma | Bilateral V, right VI, and IX palsy | Ear pain, TMJ dysfunction | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Involvement of infratemporal fossa |

| 7 | Squamous cell carcinoma | VII palsy for 22 mo | Parotid pain and swelling, preauricular pain | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Involvement of V1 |

Of the five patients with symptoms related to the auriculotemporal nerve, four (patients 3–6 in Table 2) had clinical signs of cranial nerve palsy involving V3 and imaging findings of perineural tumor growth along this branch. Three of these four patients also had further extension of the tumor, with involvement of the infratemporal fossa in one (patient 6 in Table 2), involvement of the masticator space in one (patient 4 in Table 2), and intracranial tumor growth along the middle meningeal artery in one (patient 3 in Table 2) (Fig 4). In the remaining patient (patient 7 in Table 2) of the five patients with symptoms related to the auriculotemporal nerve, the initial MR image revealed no signs suggestive of V3 involvement, but follow-up MR images obtained 12 months later showed clear evidence of V3 and cavernous sinus involvement (Fig 5).

Fig 4.

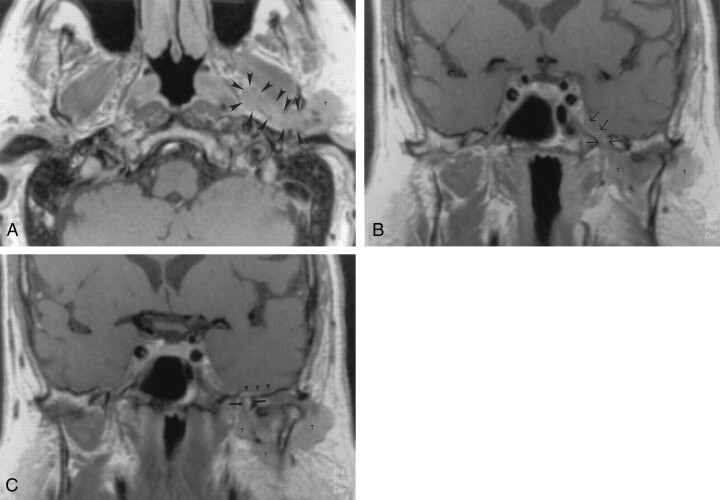

Contrast-agent–enhanced T1-weighted MR images (700/15) obtained in a 71-year-old man with skin cancer, who had TMJ tenderness and discomfort in the left ear. Symptoms related to V3 developed 8 months later.

A, Axial image shows a parotid gland mass (T) that extends medially along the expected course of the auriculotemporal nerve (arrowheads) into the parapharyngeal space.

B and C, Coronal images show the superior extension of the tumor along V3 (arrows in B) and middle meningeal artery (arrows in C) to involve the intracranial structures. Subtle dural enhancement is seen along the floor of the temporal fossa on the left (arrowheads in C). Note the normal appearance of V3 on the right. T indicates tumor. Image in C is slightly posterior to the image in B.

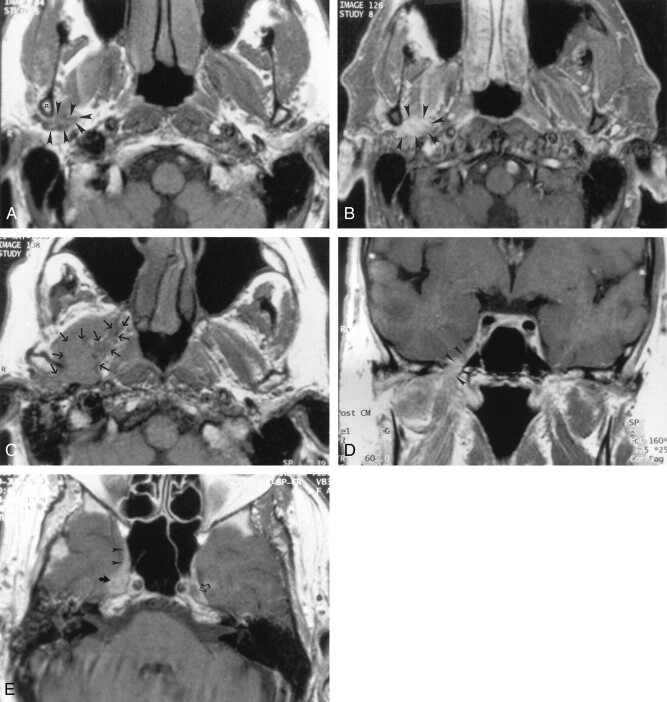

Fig 5.

MR images obtained in a 70-year-old man with skin cancer who had progressive right facial nerve weakness. Cross-sectional CT (not shown) and MR imaging were performed to evaluate the patient’s facial weakness and preauricular pain.

A, Axial nonenhanced T1-weighted image (600/14) shows a subtle area of soft tissue (arrowheads) posterior and medial to the ramus of the mandible (R) on the right side that is abnormal when compared with the left.

B, Gadolinium-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (500/14) obtained at the same level as in A shows marked enhancement of the area of abnormal soft tissue (arrowheads) in A. This finding was interpreted as normal at an outside institution.

C, Repeat nonenhanced T1-weighted image (600/14) obtained 12 months after the first MR examination shows the extensive progression of the tumor (arrows), with now obvious infiltration of the parapharyngeal space on the right.

D and E, Coronal (D) and axial (E) contrast-agent–enhanced T1-weighted images (600/14) show the growth of the tumor along V3 (arrowheads in D) into the Meckle cave (solid arrow in E) and cavernous sinus (arrowheads in E). Note the normal appearance of the Meckle cave on the left side (open arrow in E).

Both patients without symptoms related to the auriculotemporal nerve (patients 1 and 2 in Table 2) had imaging findings suggestive of V3 involvement. One had numbness in the V3 distribution (patient 2 in Table 2), and the trigeminal ganglion and cistern were invaded 7 months later. The other patient (patient 1 in Table 2) had no clinical signs of cranial nerve palsy of the trigeminal nerve and no imaging findings of skull base invasion, intracranial extension, or involvement of adjacent anatomic structures. This patient was lost to follow-up.

Five of the seven patients had imaging findings consistent with perineural tumor spread along the facial nerve main trunk. The results are summarized in Table 2.

The results presented herein showed similar distributions in the extent of the tumor and presenting symptoms in the group with pathologically proved findings and in the group with unproved findings. In both groups, more than 50% of patients (four of seven in the confirmed group and five of seven in unconfirmed group) had symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction, such as periauricular pain and TMJ dysfunction and/or tenderness. In both groups, all subjects but one had findings of tumor growth along V3. Also, involvement of the facial nerve main trunk in both groups was similar, with no cross-sectional findings of tumor spread in one subject in the pathologically confirmed group and in two in the unconfirmed group.

In four patients, the cross-sectional images initially were misinterpreted. All four patients came to our institution, but the imaging studies were performed at other clinical facilities. Three of patients underwent CT and MR imaging, and one underwent only MR imaging. In three of these patients, the extent of the disease was confirmed at surgery. In one patient, the delay in treatment was shorter than 2 months. In the other three patients, the delays were 4, 11, and 12 months (average, 8.7 months) (Fig 5).

Discussion

Anatomy

The auriculotemporal nerve is formed by two roots that arise from V3 below the skull base (Figs 6 and 7). At its origin, the auriculotemporal nerve extends in the plane between the lateral pterygoid muscle and the posterior fasciculi of the tensor veli palatini muscle within a vascular sheath of connective tissue. The upper nerve root usually is larger and lateral to the middle meningeal artery (Fig 6B). It courses posteroinferiorly, slightly below the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The lower root typically is smaller, medial to the middle meningeal artery, and laterally concave because of the indentation caused by the middle meningeal artery (Fig 6B). Posterior to the middle meningeal artery, the nerve roots coalesce to a short trunk that is usually in contact with the medial aspect of the TMJ (Figs 6 and 7). The auriculotemporal nerve then pierces the parotid fascia and enters the retromandibular region of the parotid gland. The auriculotemporal nerve typically lies parallel to the posterior border of the mandible and slightly superior to the bifurcation of the external carotid artery into the maxillary and superficial temporal arteries (9) (Fig 7). Within the parotid gland, it breaks up in a spray of branches that immediately and abruptly diverge (Fig 6). At dissection, the following branches are seen consistently (9): 1) Anterior and posterior communicating ramus with the facial nerve (Fig 6). These two communicating rami join the facial nerve within the parotid gland just posterior to the masseter muscle. They provide sensory fibers for the zygomatic, buccal, and mandibular divisions of the facial nerve to the skin (Fig 2 and 6). 2) Superior and inferior nerves to the external acoustic meatus. Those branches course between the bony and cartilaginous portions of the external auditory canal posteriorly and supply the skin of the external meatus and portions of the tympanic membrane (Fig 6A). 3) Anterior auricular nerve. This nerve branch supplies the skin of the anterior superior portion of the auricule (helix and tragus) (Fig 6A). 4) Superficial temporal ramus. This branch is the origin of multiple small twigs supplying the TMJ and capsule. The bulk of this branch, however, courses laterally and superiorly to supply the skin of the temporal region (Fig 6A).

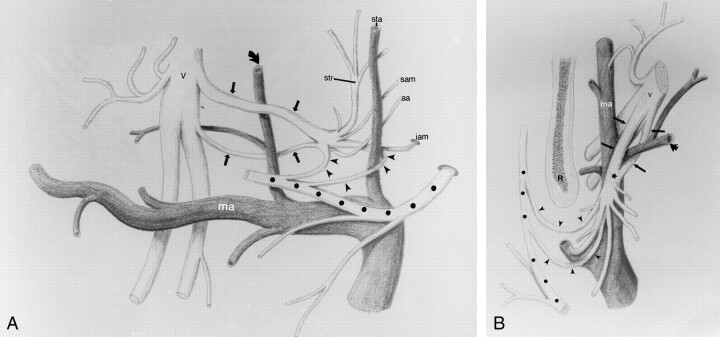

Fig 6.

Drawings depict the relationship between the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (V), auriculotemporal nerve, facial nerve, and the maxillary artery (ma) and its branches. The auriculotemporal nerve arises from V3 from two roots (thin arrows). The middle meningeal artery (thick arrow) courses between the two rootlets, which coalesce, just posterior to the artery, to form a short trunk (★ in B). The trunk forms multiple branches with the anterior and posterior communicating rami (arrowheads), joining the facial nerve (★) within the parotid gland.

A, Coronal projection. aa indicates the anterior auricular nerve; iam, inferior nerve to the external acoustic meatus; sam, superior nerve to the external acoustic meatus; sta, superficial temporal artery; and str, superficial temporal ramus.

B, Axial projection. R indicates the mandibular ramus.

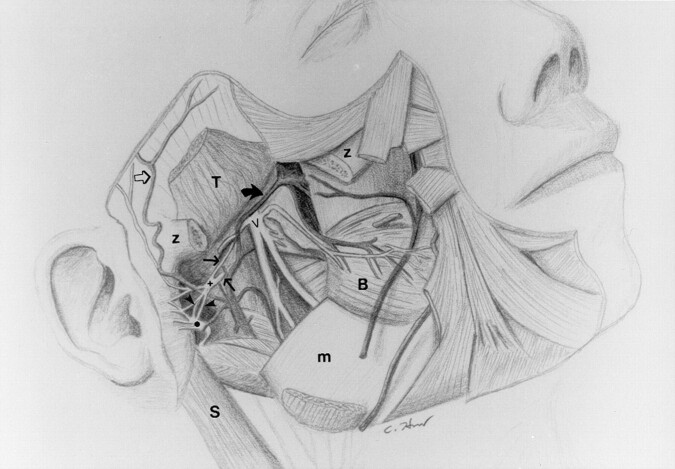

Fig 7.

Drawing illustrates the relationship between V3 (V), the auriculotemporal nerve, the facial nerve (•), and the maxillary artery (thick solid arrow) and its branches to the adjacent musculature and bony structures. Thin solid arrows indicate the roots of the auriculotemporal nerve; open arrow, superficial temporal artery; arrowheads, anterior and posterior communicating rami of the auriculotemporal nerve; B, buccinator muscle; m, mandible; S, sternocleidomastoid muscle; T, temporalis muscle; z, partially removed zygomatic arch; and +, trunk of the auriculotemporal nerve.

Summary of Results

Perineural tumor spread is a relatively frequent feature of adenoid cystic carcinoma or skin cancer in the head and neck region, which most commonly affects the facial nerve and V2, as well as V3 (2). In the past years, tumor growth along preexisting neural communications between the facial nerve and the trigeminal nerve have been described (5–7). The major known neural communications between these two nerves include the vidian nerve, greater superficial petrosal nerve, and auriculotemporal nerve.

Although only eight of the 15 patients in this study underwent pathologic analysis, the diagnosis of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve in the other seven patients seems to be a reasonable extension of the diagnostic experience, because every patient had symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction (two patients), further extension to involve V3 (two patients), or both (three patients). Only one false-positive diagnosis of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve was made; it was in a patient without symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction and without imaging findings of V3 involvement (Fig 3). A review of the CT scans in this patient, in which the reviewers had knowledge of the negative surgical and pathologic findings regarding perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve, revealed that the extension of the tumor was parallel to, but more cephalad than, the level of the auriculotemporal nerve itself (Fig 3). This example stresses an important point: the ability to identify perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve, and not only the extension of the tumor into the parotid gland in the retromandibular area, with a high degree of confidence is important. However, the level must also be identified, because the auriculotemporal nerve is located just above the point at which the external carotid artery branches into the maxillary and superficial temporal arteries. Retrospectively, this detail was overlooked because multiple CT scans were obtained between this bifurcation point of the external carotid artery and the level of medial tumor growth.

This summary of the results indicates that symptoms related to the ear and TMJ, as listed earlier, might be a sign of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve. Careful evaluation of the expected anatomic course of the auriculotemporal nerve, as described previously, is essential in making this diagnosis. Even in patients with such symptoms but without a known primary site, the course of the auriculotemporal nerve should be evaluated, because a skin lesion might have been resected in the recent or remote past, without pathologic evaluation of the tissue. However, lack of such symptoms does not necessarily exclude tumor growth along the auriculotemporal nerve.

Additional clues for diagnosing or suspecting perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve include cross-sectional findings of tumor spread along V3, either alone or in combination with facial nerve main trunk involvement. In our patient population, only one patient in the group with pathologically confirmed findings had isolated tumoral involvement of the auriculotemporal nerve (Fig 1).

Four of our patients were examined primarily at an outside institution. Review of the cross-sectional images at our facility revealed that they were misinterpreted, and diagnoses were delayed as long as 12 months. Three of these patients had symptoms related to auriculotemporal nerve dysfunction at the time of their presentation at the outside institution. All of the patients also had cross-sectional findings of V3 involvement that were not reported at the initial interpretation of the images.

To our knowledge, imaging of perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve has not been extensively described in the literature. Understanding of the regional anatomy of the auriculotemporal nerve, as well as of symptoms related to dysfunction of this nerve, is crucial in diagnosing perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve. Correct diagnosis is essential to planning treatment and accurately determining the prognosis.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the position and course of the auriculotemporal nerve is crucial in diagnosing perineural tumor spread along this branch in patients with known skin lesions or parotid gland tumors. Symptoms related to the ear or TMJ might be an important clinical clue to this diagnosis; however, lack of such symptoms does not exclude perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve. Involvement of V3 alone or in combination with the facial nerve main trunk, as well as extension into adjacent anatomic structures, might help in determining if tumor growth along the auriculotemporal nerve is present.

Footnotes

Presented at the ICHNR meeting 1994.

References

- 1.Williams LS, Mancuso AA, Mendehall WM. Perineural spread of cutaneous squamous and basal cell carcinoma: CT and MR detection and its impact on patient management and prognosis. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol Physics 2001;49:1061–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsberg LE. Imaging of perineural tumor spread in head and neck cancer. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 1999;20:175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtin HD, Wolfe P, Snyderman N. The facial nerve between the styloid foramen and the parotid: computed tomographic imaging. Radiology 1983;149:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldemeyer KS, Mathews VP, Righi PD, Smith RR. Imaging features and clinical significance of perineural spread or extension of head and neck tumors. Radiographics 1998;18:97–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg LE, DeMonte F, Gillenwater AM. Greater superficial petrosal nerve: anatomy and MR findings in perineural tumor spread. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:389–393 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandolfo I, Gaeta M, Blandino A, Salvi L, Longo M. Case report: MR imaging of perineural metastasis along the vidian nerve. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;13:498–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blandino A, Gaeta M, Minutoli F, Pandolfo I. CT and MR findings in neoplastic perineural spread along the vidian nerve. Eur Radiol 2000;10:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtin HD, Williams R, Johnson J. CT of perineural tumor extension: pterygopalatine fossa. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1984;5:731–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumel JJ, Vanderheiden JP, McElenney JE. The auriculotemporal nerve of man. Am J Anat 1971;130:431–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]