Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is an advanced MR technique that describes the movement of water molecules by using two metrics, mean diffusivity (MD), and fractional anisotropy (FA), which represent the magnitude and directionality of water diffusion, respectively. We hypothesize that alterations in these values within the tissue surrounding brain tumors reflect combinations of increased water content and tumor infiltration and that these changes can be used to differentiate high-grade gliomas from metastatic lesions.

METHODS: DTI was performed in 12 patients with high-grade gliomas and in 12 with metastatic lesions. DTI measurements were obtained from regions of interest (ROIs) placed on normal-appearing white matter and on the vasogenic edema, the T2 signal intensity abnormality surrounding each tumor.

RESULTS: The peritumoral region of both gliomas and metastatic tumors displayed significant increases in MD (P < .005) and significant decreases in FA (P < .005) when compared with those of normal-appearing white matter. Furthermore, the peritumoral MD of metastatic lesions measured significantly greater than that of gliomas (P < .005). Peritumoral FA measurements, on the other hand, showed no such discrepancy.

CONCLUSION: When compared with an internal control, diffusion metrics are clearly altered within the vasogenic edema surrounding both high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors, reflecting increased extracellular water. Although peritumoral MD can be used to distinguish high-grade gliomas from metastatic tumors, peritumoral FA demonstrated no statistically significant difference. The FA changes surrounding gliomas, therefore, can be attributed not only to increased water content, but also to tumor infiltration.

MR diffusion tensors are constructed from diffusion measurements obtained in non-collinear directions and converted into symmetric 3 × 3 matrices that describe the trajectory field of moving water molecules in three-dimensional space. A tensor matrix can be converted into three differential equations, which, when solved, yield an eigenvector that reflects the aggregate magnitude and direction of diffusion in three-dimensional space. Using this eigenvector, we calculate the mean diffusivity (MD), which serves as our measure of magnitude. Various methods and formulae have been developed to quantify directionality. In this study, we use fractional anisotropy (FA), a root-mean-square formula that yields values between 0 (perfectly isotropic diffusion) and 1 (the hypothetical case of a long cylinder one water molecule thick) (1).

High-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors often contain signal intensity heterogeneity secondary to necrosis and susceptibility artifact. Because of this heterogeneity, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics obtained from within the tumor can be imprecise or inaccurate. Fortunately, most of these cases display some degree of surrounding T2 signal intensity abnormality, traditionally termed vasogenic edema. Analysis of these peritumoral regions may prove to be more robust than analysis of the lesion itself. Added benefits of studying peritumoral changes include the ability to take measurements in the setting of postoperative recurrence and in the setting of treatment response. In one study, for example, peritumoral DTI measurements were used to follow the extent of vasogenic edema in brain tumor patients who had undergone dexamethasone treatment (2). We hypothesize that 1) both high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors alter the MD and FA in the peritumoral region, as compared with those of normal-appearing contralateral white matter, and 2) high-grade gliomas elicit greater FA changes as a result of tumor infiltration. It should be noted, therefore, that what we call the peritumoral region may, in fact, contain clusters of malignant cells that are neither prominent enough to show nor vascular enough to enhance on T1- or T2-weighted images.

Methods

A two-tier case-selection process was implemented. First, consecutive brain tumor patients who underwent MR imaging with DTI were selected for region-of-interest (ROI) analysis if vasogenic edema was present. These cases were studied retrospectively (that is, without identifying the patients before MR imaging) but with blinding to regard to disease type. Secondly, cases were included in the study if the tumor was classified into one of two categories: 1) high-grade glioma, namely glioblastoma multiforme or anaplastic astrocytoma (AA), or 2) solitary intra-axial metastatic neoplasm. Therefore, tumors such as meningiomas and lymphomas were excluded. By using these criteria, 24 patients (12 women, 12 men; average age, 50.0 years ± 14.2; range, 28–77 years) were included in our study. Approval for these studies was obtained from the Board of Research Associates, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Studies were performed with a 1.5-T system (Magnetom Vision; Siemens, Iselin, NJ) by using a diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE/NEX, 4000/98/4; number of sections, seven; section thickness, 3.0 mm; section separation, 0.4 mm; matrix 128 × 128; FOV, 315 × 315 mm; and total imaging time,1 minute 44 seconds. A total of seven image sets were acquired: six with non-collinear diffusion-weighting gradients with a b value of 900 s/mm2 and one without diffusion weighting. The diffusion gradient directions (Gx, Gy, Gz) were as follows: (1, 1, 0), (0, 1, 1), (1, 0, 1), (−1,1,0), (0,−1,1), and (1,0,−1). The dual-echo DTI sequence was carefully designed to minimize eddy currents and geometric distortion. All raw data were transferred to a workstation (Sun SPARC station; Sun Microsystems, Palo Alto, CA) for analysis.

Voxel by voxel, the MD and FA were calculated by using the following standard algorithms:

|

1) |

and

|

2) |

where λn = the eigenvalues describing a diffusion tensor. For each section, these values are composed into MD and FA maps.

On T1- and T2-weighted images through the tumor, one author (S.L.) applied four circular ROIs to the peritumoral T2 signal intensity abnormality and four such ROIs within the corresponding contralateral normal-appearing white matter, under the guidance of a board-certified neuroradiologist (S.C.). The author placed these fixed 3.75-mm-diameter ROIs anteriorly, medially, posteriorly, and laterally—adjacent to the enhancing portion of the tumor—to obtain the most random sampling with consistency among all patients (Fig 1A and B). For the more cortically based tumors, inapplicable ROIs would be distributed evenly in the adjacent white matter. Placement of ROIs within gray matter structures was avoided because of the inherent DTI differences between white matter and gray matter (3).

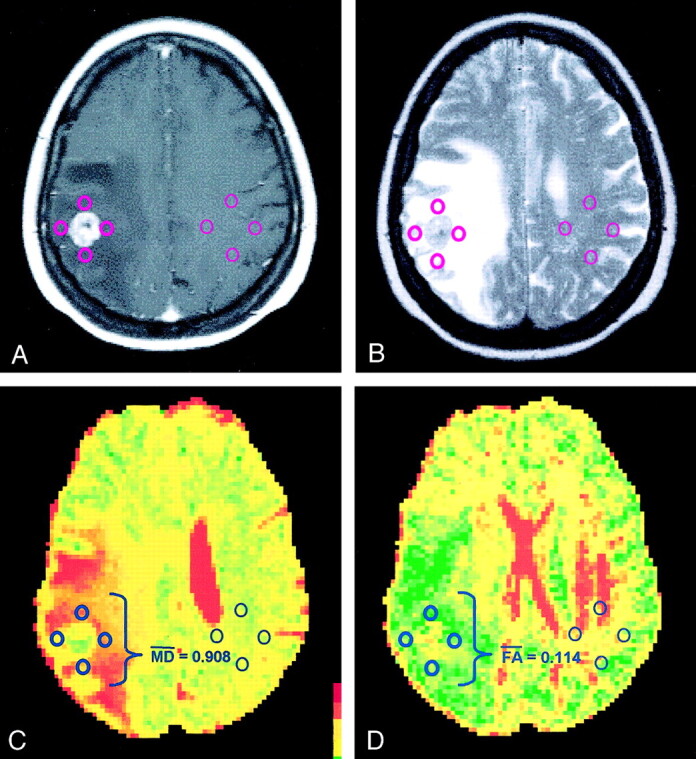

Fig 1.

Images in a patient with lung carcinoma.

A, Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image demonstrates an enhancing mass adjacent to the central sulcus on the right side.

B, ROIs are placed within the hyperintense vasogenic edema on this T2-weighted MR image and within the corresponding contralateral white matter.

C, MD overlay map renders a mean MD of 0.908 × 10−3 mm2/s.

D, FA overlay map renders a mean FA of 0.114. The peritumoral DTI metrics are consistent with lung metastasis.

By using these ROIs in conjunction with the MD and FA maps (Fig 1C and D), the mean peritumoral MD and FA, as well as the mean MD and FA in normal-appearing white matter, were calculated for each patient. Statistical analysis consisted of unpaired Student t testing with statistical significance established at P < .005. The Pearson coefficient was applied as a measure of correlation, with R>0.80 established as a strong correlation.

Results

The 12 cases of high-grade gliomas were postoperatively classified into the following subtypes: nine cases of glioblastoma multiforme and three cases of anaplastic astrocytoma . The 12 metastatic brain lesions were determined to arise from the following primary sites: five lung carcinomas, two breast carcinomas, two melanomas, one testicular yolk sac tumor, one osteogenic sarcoma, and one undifferentiated sarcoma. These diagnoses, along with the mean values of FA and MD measured in normal-appearing white matter and the peritumoral regions of both patient groups, are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. As stated earlier, the term peritumoral applies to the region surrounding tumoral enhancement that may contain malignant cells.

TABLE 1:

Mean DTI metrics in patients with high-grade gliomas

| Patient | Diagnosis | Peritumoral Signal Abnormality |

Normal-Appearing White Matter |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (×10−3 mm2/s) | FA | MD (×10−3 mm2/s) | FA | ||

| 1 | Anaplastic astrocytoma | 0.602 | 0.240 | 0.387 | 0.529 |

| 2 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.586 | 0.207 | 0.428 | 0.390 |

| 3 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.764 | 0.183 | 0.403 | 0.421 |

| 4 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.789 | 0.178 | 0.361 | 0.486 |

| 5 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.460 | 0.279 | 0.375 | 0.501 |

| 6 | Anaplastic astrocytoma | 0.559 | 0.239 | 0.398 | 0.526 |

| 7 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.658 | 0.338 | 0.382 | 0.480 |

| 8 | Anaplastic astrocytoma | 0.725 | 0.190 | 0.398 | 0.395 |

| 9 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.716 | 0.206 | 0.373 | 0.420 |

| 10 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.450 | 0.248 | 0.376 | 0.362 |

| 11 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.559 | 0.373 | 0.548 | 0.688 |

| 12 | Glioblastoma multiforme | 0.603 | 0.301 | 0.391 | 0.400 |

TABLE 2:

Mean DTI metrics in patients with metastatic brain tumors

| Patient | Diagnosis | Peritumoral Signal Abnormality |

Normal-Appearing White Matter |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (×10−3 mm2/s) | FA | MD (×10−3 mm2/s) | FA | ||

| 1 | Breast carcinoma | 0.697 | 0.244 | 0.399 | 0.428 |

| 2 | Melanoma | 0.723 | 0.244 | 0.415 | 0.412 |

| 3 | Breast carcinoma | 0.838 | 0.149 | 0.436 | 0.653 |

| 4 | Testicular carcinoma | 0.811 | 0.194 | 0.410 | 0.471 |

| 5 | Breast carcinoma | 0.743 | 0.174 | 0.398 | 0.369 |

| 6 | Melanoma | 0.701 | 0.183 | 0.369 | 0.508 |

| 7 | Lung carcinoma | 0.908 | 0.114 | 0.381 | 0.338 |

| 8 | Lung carcinoma | 0.639 | 0.229 | 0.385 | 0.400 |

| 9 | Lung carcinoma | 0.789 | 0.168 | 0.376 | 0.428 |

| 10 | Osteosarcoma | 0.943 | 0.182 | 0.408 | 0.362 |

| 11 | Lung carcinoma | 1.002 | 0.157 | 0.407 | 0.356 |

| 12 | Undifferentiated sarcoma | 0.788 | 0.140 | 0.387 | 0.404 |

In both high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors, the values of normal-appearing white matter in the contralateral brain and those in the peritumoral abnormality were significantly different. Around gliomas, the average MD increased from 0.402 (in normal-appearing white matter) to 0.622 × 10−3 mm2/s (P < .005), while the FA decreased from 0.466 to 0.248 (P < .005). Around metastatic lesions, the average MD increased from 0.397 to 0.798 × 10−3 mm2/s (P < .005), while the FA decreased from 0.427 to 0.181 (P < .005).

The MD of the signal intensity abnormality surrounding high-grade gliomas ranged from 0.450 × 10−3 mm2/s to 0.789 × 10−3 mm2/s, averaging (0.622 ± 0.111) × 10−3 mm2/s (mean ± SD). The MD of the vasogenic edema surrounding metastatic lesions ranged from 0.639 × 10−3 mm2/s to 1.002 × 10−3 mm2/s, averaging (0.798 ± 0.109) × 10−3 mm2/s. With an unpaired Student t test, the data between the peritumoral MD of high-grade gliomas and the metastatic tumors showed a statistically significant difference (P < .005).

The FA of the signal intensity abnormality surrounding high-grade gliomas ranged from 0.178 to 0.373, with a mean of 0.248 ± 0.063. The FA of the vasogenic edema surrounding metastatic lesions ranged from 0.114 to 0.244, with a mean of 0.181 ± 0.041. In contrast to the MD, the difference between the FA of the two categories did not show statistical significance.

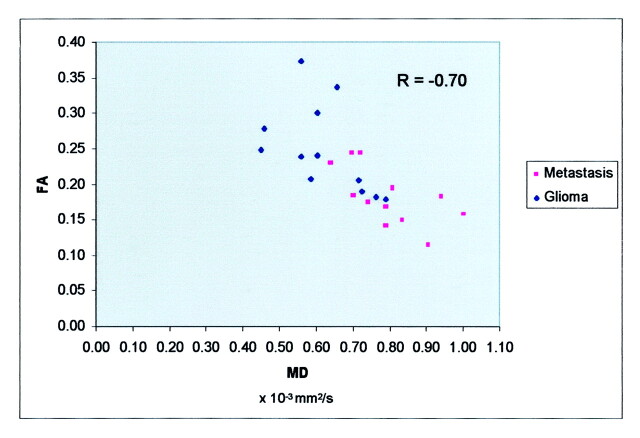

The data are displayed in a scatterplot (Fig 2). The Pearson correlation coefficient R was used to quantify the relationship of MD and FA; the two variables were not highly correlated (R = −0.70).

Fig 2.

Scatterplot of FA versus MD demonstrates lack of high correlation between the two variables (R = −0.70). The data in the metastasis group tend to lie within the higher range of MD, when compared with the data in the glioma group (P < .005). Along the FA axis, no such statistically significant discrepancy was observed.

Discussion

DTI has been used to describe normal brain tissue as well as various disease states. Decreases in diffusivity, thought to be associated with cell swelling and consequent reduction in extracellular space, are seen in acute infarction. Abscesses and epidermoid tumors also display diminished diffusivity, which theoretically occurs through the viscosity of their contents (4). Various intracranial tumors have also been evaluated by using conventional diffusion imaging (5, 6). With DTI, derangement of anisotropy has been described in stroke (7, 8), multiple sclerosis (9), and even schizophrenia (10). The anisotropy of various structural abnormalities has also been studied (11, 12).

On conventional MR images, high-grade gliomas and solitary metastatic brain tumors often display similar signal intensity characteristics and contrast enhancement patterns. Figure 3 demonstrates a left temporal tumor that was neither clearly high-grade glioma nor clearly metastasis. Most of these tumors are surrounded by a T2 signal intensity abnormality that has traditionally been termed vasogenic edema. By appearance alone, these peritumoral changes generally cannot be used to differentiate glioma from metastatic disease; however, because the vasogenic edema involves an increased water component (13), we used peritumoral DTI to study the molecular motion of the water.

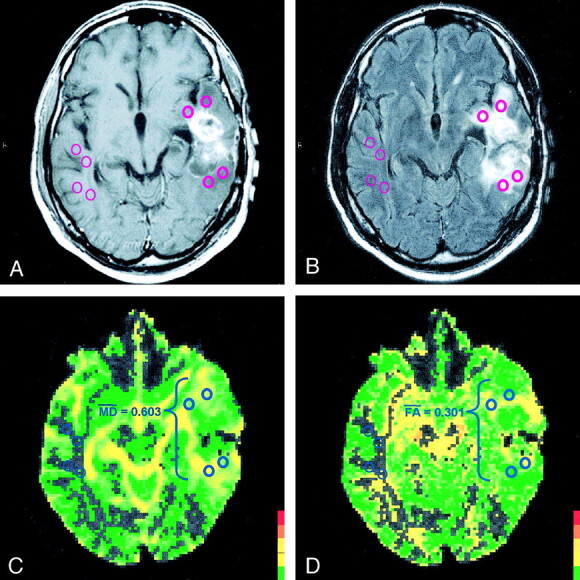

Fig 3.

Images in a patient with glioblastoma multiforme.

A, Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image demonstrates an enhancing mass in the left temporal lobe that is not clearly high-grade glioma nor clearly metastasis on this conventional MR image.

B, ROIs are placed within the hyperintense vasogenic edema on a T2-weighted MR image and within the corresponding contralateral white matter.

C, MD overlay map renders a mean MD of 0.603 × 10−3 mm2/s.

D, FA overlay map renders a mean FA of 0.301. The peritumoral DTI metrics are consistent with glioblastoma multiforme.

In this study, we confirmed our first hypothesis by showing statistically significant changes between the MD and FA values of normal-appearing white matter and those of the peritumoral T2 signal intensity abnormality. Surrounding both gliomas and metastatic lesions, there was an increase in MD and a decrease in FA, which are best explained by increased extracellular bulk water. The addition of free water to any tissue increases the amount of diffusion (ie, increases the MD) and causes more disorganized diffusion (ie, decreases the FA), similar to the values seen in water-laden ventricles.

Our second hypothesis involved the differentiation of high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors by using FA. We disproved our hypothesis by showing that the changes in peritumoral FA do not differ significantly between high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors. However, the peritumoral MD surrounding metastatic lesions proved to be significantly greater than that of surrounding high-grade gliomas. We believe that MD is primarily determined by increased extracellular water, and therefore, metastasis-related vasogenic edema reflects greater increased water content of the surrounding tissue. These results are displayed in two cases from our study (Figs 1, 3).

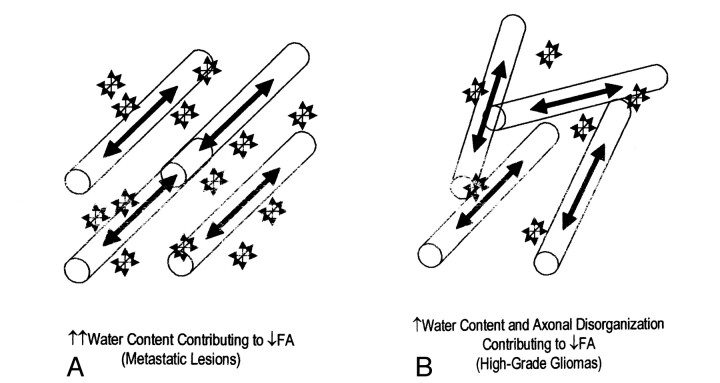

Because we know that both increased water content and tumor infiltration can lead to more disorganized diffusion, the decreased FA surrounding high-grade gliomas cannot be attributed solely to one or the other. In fact, a more accurate model of the vasogenic edema surrounding gliomas includes contributions from both of these processes (Fig 4). The glioma-related FA changes induced by both increased water content and tumor infiltration are comparable to the metastasis-related changes caused by the increased water content alone.

Fig 4.

Schematics illustrate the factors behind the comparable change in peritumoral FA.

A, Water content and axonal disorganization contributing to decreased FA.

B, Water content contributing to decreased FA

Limitations of our study include a relatively small sample population, the retrospective approach to case selection, and the subjective placement of the ROIs. Indeed, selection of the ROI itself can affect the DTI metrics more than the vasogenic edema (3). There are even varying FA values among different white matter structures (14). In this study, we established guidelines to constrain the peritumoral ROIs to white matter. When obtaining the internal control, we sampled the contralateral white matter that corresponded most closely to the peritumoral ROIs.

Peritumoral DTI can be a powerful tool in the diagnostic and surgical management of high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors. Specifically, preoperative determination of high-grade glioma versus metastatic lesion can lead to differing radiographic management. In addition, the peritumoral region theoretically can be followed after gross total resection. Thus, peritumoral DTI also has the potential to become a useful tool in the monitoring of tumor recurrence and treatment response.

Conclusion

Using DTI, we have demonstrated that there are clear differences in the diffusion characteristics of the vasogenic edema surrounding brain tumors, when compared with those of normal-appearing white matter. In addition, peritumoral MD specifically may be useful in the preoperative discrimination of high-grade gliomas and metastatic tumors; however, the changes in FA showed no such statistical significance. The comparable decrease in FA for both disease processes is attributable to a large water influx surrounding metastatic tumors and contributions of both increased water content and tumor infiltration surrounding gliomas.

References

- 1.Alexander AL, Hasan K, Kindlmann G, et al. A geometric analysis of diffusion tensor measurements of the human brain. Magn Res in Med 2000;44:283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastin ME, Delgado M, Whittle IR, et al. The use of diffusion tensor imaging in quantifying the effect of dexamethasone on brain tumours. NeuroReport 1999;10:1385–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe O, Aoki S, Hayashi N, et al. Normal aging in the central nervous system: quantitative MR diffusion-tensor analysis. Neurobiol Aging 2002;23:433–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kono K, Inoue Y, Nakayama K, et al. The role of diffusion-weighted imaging in patients with brain tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1081–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krabbe K, Gideon P, Wagn P, et al. MR diffusion imaging of human intracranial tumours. Neurorad 1997;39:483–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugahara T, Korogi Y, Kochi M, et al. Usefulness of diffusion-weighted MRI with echo-planar technique in the evaluation of cellularity in gliomas. J Magn Res Imaging 1999;9:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowley HA, Grant E, Roberts TPL. Diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimag Clin N Am 1999;9:343–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werring DJ, Toosy AT, Clark CA, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging can detect and quantify corticospinal tract degeneration after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2000;69:269–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bammer R, Augustin M, Strasser-Fuchs S, et al. Magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging for characterizing diffuse and focal white matter abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Magn Res in Med 2000;44:583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foong J, Maier M, Clark CA, et al. Neuropathological abnormalities of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2000;68:242–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieshmann UC, Clark CA, Symms MR, et al. Reduced anisotropy of water diffusion in structural cerebral abnormalities demonstrated with diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Res Imaging 1999;17:1269–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wieshmann UC, Symms MR, Parker GJM, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging demonstrates deviation of fibres in normal appearing white matter adjacent to a brain tumour. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2000;68:501–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferszt R, Cervós-Navarro J. Brain edema: pathology, diagnosis, and therapy. New York: Raven Press;1980 [PubMed]

- 14.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan E, Hedehus M, et al. Age-related decline in brain white matter anisotropy measured with spatially corrected echo-planar diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Res in Med 2000;44:259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]