Abstract

Background:

The lack of success of standard therapies for medulloblastoma has highlighted the need to plan a new therapeutic approach. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the novel treatment strategies based on the molecular characterization and risk categories of the medulloblastoma, also focusing on up-to-date relevant clinical trials and the challenges in translating tailored approaches into clinical practice.

Methods:

An online search of the literature was carried out on the PubMed/MEDLINE and ClinicalTrials.gov websites about molecular classification of medulloblastomas, ongoing clinical trials and new treatment strategies. Only articles in the English language and published in the last five years were selected. The research was refined based on the best match and relevance.

Results:

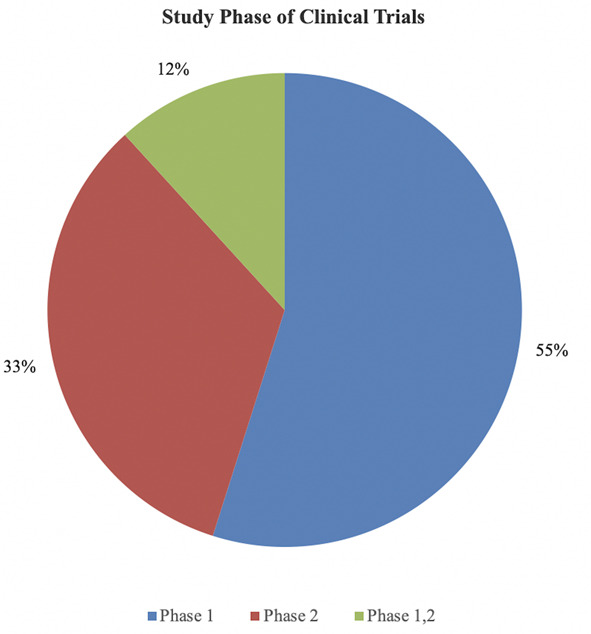

A total 58 articles and 51 clinical trials were analyzed. Trials were of phase I, II, and I/II in 55%, 33% and 12% of the cases, respectively. Target and adoptive immunotherapies were the treatment strategies for newly diagnosed and recurrent medulloblastoma in 71% and 29% of the cases, respectively.

Conclusion:

Efforts are focused on the fine-tuning of target therapies and immunotherapies, including agents directed to specific pathways, engineered T-cells and oncoviruses. The blood-brain barrier, chemoresistance, the tumor microenvironment and cancer stem cells are the main translational challenges to be overcome in order to optimize medulloblastoma treatment, reduce the long-term morbidity and increase the overall survival. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Adoptive Immunotherapies, Medulloblastoma, Sonic Hedgehog Medulloblastoma, Target Therapy, Wingless Medulloblastoma

Background

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant pediatric tumor, accounting for 15-20% of childhood brain neoplasms.1 MB usually occurs in the posterior fossa and has a high risk for early leptomeningeal spread at first diagnosis.

Current multimodal therapies, including surgery and radiochemotherapy, lengthens the long-term survival to 60-80%, but 33% of children diagnosed die in five years, the median survival for recurrent MBs being less than twelve months. Treatment also leads to severe and debilitating long-term complications.2-5

The persistence of high mortality rates and severe side effects of standard treatments has highlighted the need for more effective and sophisticated therapeutic strategies.

Advanced molecular research and whole-genome sequence analysis in many neurological and neurooncological pediatric central nervous system (CNS) pathologies6-9 has made it possible to deepen the understanding of the heterogeneity and genome make-ups of MBs, resulting in the novel classification underpinned on different molecular features.10-15

The subgroups have substantial biological differences, express specific markers of prognosis leading to a more accurate risk stratification, and underly distinct deregulated signaling pathways, exploitable as potential therapeutic targets.4, 16-18

Breakthroughs of risk-adapted interventions based on molecular characteristics, including target agents, immunotherapies and stem-cell strategies, have made it possible to plan an effective personalized approach and have reduced long-term morbidity.

In this article, we outline the molecular landscape of MB subtypes, along with prognostic markers, and examine the ongoing transition toward the innovative molecularly targeted strategies; focusing on the therapeutic options currently available, most relevant clinical trials, and future challenges in the management of newly diagnosed and recurrent MBs.

Methods

An online search of the literature was conducted on the PubMed/MEDLINE (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) platform and the ClinicalTrials.gov website (https://clinicaltrials.gov). For the PubMed/MEDLINE search the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) database has been used and the terms “Target Therapy”, “Molecular Classification”, “Adoptive Immunotherapy”, “Cell-Based Therapy”, “Stem Cell Therapy” and “Tailored Therapy” have been chosen; combined with the following keywords: “Pediatric Brain Tumors”, “Pediatric Central Nervous System tumors”, “Brain tumors in childhood” and “Medulloblastoma”.

Only articles in English or translated into English, published in the last five years, and concerning neuro-oncology were selected and then sorted based on the best match and relevance.

On the ClinicalTrials.gov website, the search terms were “Medulloblastoma”, “Pediatric Malignant Brain Tumor”, “Pediatric Brain Cancer” and “Pediatric central nervous system Neoplasms”. No restrictions for drug name, study phase and recruitment status country have been applied.

A descriptive analysis has been reported about the most relevant studies of the overall research.

Results

1 Molecular classification of MBs

Based on histopathological characteristics, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified MBs in classic, desmoplastic-nodular, with extensive nodularity, anaplastic, and large cell types.19

Several cytogenetic studies and the increased understanding of the pathophysiology of several CNS pediatric pathologies 20-22 and, within this context, the biological heterogeneity of MBs have been translated into classification refinements.

The four subtypes, based on genome sequencing, DNA analysis and phenotypic profiles, are as it follows: wingless (WNT), sonic hedgehog (SHH), Group 3 and Group 4.16, 23-25

This novel molecular subgrouping has potential prognostic implications, so the current risk stratification divides the MBs in “low”, “standard”, “high”, and “very high risk”, based on age, presence of metastases, histologic phenotype, prognostic molecular markers, and especially, molecular subtype.16-18 Table 1 and 2 report the molecular and prognostic classification of medulloblastoma (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

| Molecular Subtype | WNT | SHH | Group 3 | Group 4 |

| Proportion of MBs | 10-15% | 25% | 25% | 35% |

| Age Distribution | 10-12 years old | Bimodal, < 5-> 16 years old | < 3 years old | Children |

| Male/Female Ratio | 1:1 | 1:1 | 2:1 | 3:1 |

| Location | Midline, Fourth Ventricle | Cerebellar Hemispheres, Vermis | Midline, Fourth Ventricle | Midline, Fourth Ventricle |

| Histology | Classic, rarely LCA | DN, Classic, LCA | Classic, rarely LCA | Classic, rarely LCA |

| Metastasis | 5-10% | 15-20% | 45% | 30-40% |

| Recurrence | Rare | Local | Metastatic | Metastatic |

| Driver Genes |

|

|

|

|

| Chromosome Aberration | Monosomy 6 (> 80%) | Loss 9q (PTCH1 locus) | Isochromosome 17q | Isochromosome 17q |

| MYC status | + | + | +++ | - |

| 5-year Survival | > 90% | 70% | 40-60% | 75% |

DN: Desmoplastic-Nodular; LCA: Large Cell/Anaplastic; SHH: sonic hedgehog; WNT: wingless

Table 2.

Prognostic Classification for Medulloblastoma82

| Risk Categories | Molecular Profile | 5-year overall survival |

| Low Risk | Non-metastatic WNT-MBs | >90% |

| Localized Group 4-MBs, with loss of chromosome 11 and gain of chromosome 17 | ||

| Standard Risk | Non-metastatic SHH-MBs without p53 mutation | 76-90% |

| Group 3 non-MYC amplified | ||

| Group 4 without p53 mutation and loss of chromosome 11 | ||

| High Risk | Metastatic SHH-MBs MYC amplified | 50-75% |

| Metastatic Group 4 | ||

| Very High Risk | Metastatic Group 3 | < 50% |

| SHH-MBs MYC amplified with p53 mutation |

MBs: Medulloblastomas; SHH: Sonic Hedgehog; WNT: Wingless

1.1 WNT-MBs

WNT proteins play a central role in cell growth, proliferation, motility and homeostasis. The pathway is triggered by β-catenin protein and various kinases as transduction enhancers.

In 85-90% of the cases, the WNT-MB subgroup harbors a point mutation in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene which renders the β-catenin resistant to degradation and leads to an upregulation of the WNT pathway.18, 26-29

In 70-80% of the cases, the monosomy/diploidy of chromosome 6 and the overexpression of MYC e MYCN proteins, markers of worse prognosis, results in the activation of the WNT signalings.30, 31

Less frequent driving genetic alterations concern the DDX3X, SMARCA4 and p53 genes, with a frequency of 50%, 26% and 13%, respectively.32

WNT-MBs are the least common, accounting for 10%, with a peak incidence in 10-12 years, and almost equal male/female ratio.32 More than 90% have a classic histology, location in the midline of the fourth ventricle and relatively rare metastasis (5-10%)33.

This group has the better prognosis, with more than 90% of 5-year event-free survival.33

1.2 SHH-MBs

The hedgehog (HH) signaling pathway is involved in the proliferation of neuronal precursor cells and is fundamental for tissue maintenance and regeneration.

HH ligands bind the receptor protein patched homolog 1 (PTCH1) and activate the intracellular cascade of smoothened (SMO) proteins.

Among mammalian homologs of the hedgehog, the aberrant upregulation of the SHH signaling pathway promotes tumor formation in about 30% of MBs.18, 23, 24, 34

The typical activating mutations for the SHH subtype include the TERT in 83%, PTCH1 in almost 45%, the modulator suppressor of fused homolog (SUFU) in 10%, and SMO in 9% of the cases.35-37

In the SHH signaling pathway, SMO activates the downstream target gene FOXM1, a GLI transcription factor, which activates genes for mitosis, including PLK1 and MYCN.

The expression at a high level of FOXM1/PLK1, MYCN and GLI 1 and 2 are also prognostic markers and potential therapeutic targets.29, 38, 39

Other molecular characterizations typical of SHH-MBs are in genes coding for ErbB family proteins, such as EGFR and ERBB3, deregulation of the p53 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and the deletion of chromosome 9q (PTCH1 locus), which modifies the transcription of CDKN2A/2B, known as tumor suppressor factors.

In many cases, these mutations suggest the concomitant presence of a hereditary genetic disease such as Gorlin syndrome, associated with mutations affecting the PTCH1 and SUFU genes. The SHH subgroup, 25% of all cases, has a bimodal age distribution, less than 3 and more than 16 years, with equivalent sex ratio and the majority has nodular/desmoplastic histology.16, 40 They are frequently located in cerebellar hemispheres and vermis, and metastasis are not common.16, 34

SHH-MBs have an intermediate prognosis with 5-year overall survival of 70% after standard treatment.16

1.3 Group 3

Group 3 MBs represent 25% of all cases and are mostly characterized by amplification of various proto-oncogenes: GFI1/GFI1B (30%), MYC (16.7%), PVT1 (12%), SMARCA4 (11%) and OTX2 (10%).18

Additionally, fibroblast growth factor, tyrosine kinase receptors, and their consequent downstream signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK, are frequently deregulated. Isochromosome 17q is present in 25% of SHH cases and among those with MYC amplification (10%-17%), are strong indicators of poor prognosis.

Group 3 is limited to children (3-5 years old), with male predominance and classic, anaplastic or large-cell histology.18

This is the group with the worst prognosis, as metastases are present in 45% of the cases.16, 23

1.4 Group 4

Group 4 is the most common, accounting for 35% of MBs, with no age prevalence and high male predominance. Isochromosome 17q occurs in 80% of the cases and the mutation of the KDM6A gene is frequently detached (13%).41 The KDM6A encodes for a histone demethylase enzyme and is located on the X-chromosome, explaining the male predominance of Group 4.

Additionally, MYCN, cyclin dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) and NOTCH1, 2, 3 are commonly amplified. The expression of the NOTCH network is directly linked to therapy resistance, because it regulates the tumor’s immune response and maintains the tumor microenvironment. The overexpression of cytokine receptors and their downstream signaling, such as the JAK-STAT pathway, estrogen-related receptor γ, and Fc receptors are found in this varied genomic landscape, not yet fully explored.

However, this subtype has an intermediate prognosis, like the SHH-MBs. However, leptomeningeal spread occurs more frequently (30-40%).16, 18, 23

2 Target Therapy

2.1 HH inhibitors

The most investigated target approach concerns the inhibitors of the HH pathway and the first one discovered was cyclopamine. It binds the transmembrane domain of SMO and definitively suppresses the growth and proliferation of the tumor’s cells.16, 42

Although having excellent premises, cyclopamine did not show efficacy when applied in vivo, but led to the development of many molecules with the same drug-like properties. They were vismodegib, saridegib, sonidegib and erismodegib, all having improved pharmacokinetics and lower toxicities.43, 44 Vismodagib, an SMO antagonist, was approved by the FDA and tested in some phase I and II clinical trials. Many of these are ongoing and are evaluating the efficacy of vismodegib combined with standard chemotherapy in children and adults diagnosed with recurrent or refractory MBs (#NCT01601184, #NCT01878617). A phase II study on vismodegib, conducted in 2005, enrolled 43 patients (12 affected by SHH-MBs) and showed a 6-month progression-free survival in 41% of the SHH patients (#NCT01239316).

Sonidegib and ZSP1602, orally bioavailable drugs inhibiting the SMO pathway, are under clinical evaluation.

2.2 Bromodomain inhibitors (BET)

A recent therapeutic strategy involves the bromodomain proteins, which bind histones and modulate gene transcription. BET inhibitors, such as JQ1 and BMS-986158, have been tested in many clinical trials in order to evaluate their safety and tolerability profiles45 (#NCT03936465). In the BET family, the BRD4 protein is being evaluated as potential therapeutics target against advanced MYC-amplified MBs.46, 47

2.3 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

Tyrosine kinases enzymes catalyze the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on specific receptors, activating the intracellular transduction pathways. TKIs target oncogene growth factor receptors, including the epidermal growth factor (EGFR), the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR), the fibroblast growth factor (FGFR) and the hepatocyte growth factor (HGFR) receptors, which are involved in the cell’s maintenance, differentiation and metastasis.

MB TKIs therapy involves imatinib, gefitinib, lapatinib, dasatinib, sorafenib, sunitinib and erlotinib.

Imatinib, a PDGFR blocker, prevents the migration and invasion of MB cells; it has been investigated in several clinical trials, showing good ability for overcoming the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

Erlotinib has been proved in two clinical trials, combined with chemoradiotherapy, especially for recurrent MBs (#NCT00077454, #NCT00360854).

A phase I study demonstrated the efficacy of savolitinib, inhibitor of HGFR, in primary brain tumors, including recurrent MBs (#NCT03598244).

Many phase II clinical trials are focusing on patients carrying FGFR mutations by administering erdafitinib, an oral pan-FGFR inhibitor with promising results (#NCT03210714).

2.4 PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway controls cell growth and dissemination. Target agents directed against PI3K have given satisfactory results.

The PI3K and mTOR signaling pathways inhibitors, such as fimepinostat (#NCT03893487) and samotolisib (#NCT03213678) are tested for pediatric CNS tumors.

Wojtalla et al. reported the antitumoral potential of combination therapy involving the humanized anti-IGF-1R antibody, R1507, with PIK75, a class IA PI3K inhibitor, in recurrent MBs and neuroblastomas.48

2.5 CDK4/CDK6/pRB inhibitors

The pRB plays a fundamental role in cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. The dysregulation of the pRB signaling pathways is found in many MBs, resulting in clonal cell expansion. The pRB inactivity is caused by the overexpression of CDK4/CDK6 suppressing agents.

The restoration of pRB activity is an effective rational strategy.

Novel agents directed against CDK4/CDK6, such as ribociclib and palbociclib, proved to have strong antitumor efficacy, also in combination with the SMO inhibitor, sonidegib (#NCT03434262).

Palbociclib is evaluated in a phase I clinical trial in combination with irinotecan and temozolomide for children with central nervous system (CNS) tumors (#NCT03709680).

Ribociclib and everolimus is tested in children affected by recurrent and refractory MBs (#NCT03387020).

2.6 MDM2/MDM4/p53 inhibitors

p53 is a fundamental protein regulating the cell cycle and inducing cell apoptosis. It is mutated in almost 40% of MBs, facilitating the proliferation and spread of the tumor. p53 dysregulation is found in the WNT and SHH groups, resulting in a 40% reduction of 5-year survival and is considered one of the leading causes of treatment failure. MDM2/4, which induce p53 degradation and negatively regulate its activity, are also promising therapeutic strategies.49

Nutlin-3 selectively binds MDM2, inhibiting p53 degradation. In 2012, Annette et al. proved in vitro and in vivo the antitumor activity of nutlin-3 against MBs.50

2.7 Chemokines inhibitors

Chemokines are pivotal in tumor growth and in sustaining the tumor-related microenvironment.

CXCL12 chemokine and its CXCR4 receptor are overexpressed in many CNS tumors, and significantly higher in MBs.

In 2012, Sengupta et al. demonstrated the presence of CXCR4 in WNT and SHH-MBs, but only SHH subtype harbors the CXCR4 overexpression.51

AMD3100 (Plerixafor), a CXCR4 antagonist, has been tested in one phase I/II clinical trial, combined with chemoradiotherapy, for several CNS tumors (#NCT01977677).

2.8 Anti-Angiogenesis agents

MBs are characterized by a thriving pathological angiogenesis and, consequently, potential downstream targets are the VEGF/VEGFR, copiously expressed in WNT and SHH-MBs. Anti-angiogenic therapies applied for MB involve bevacizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against VEGF-A, in combination with conventional chemotherapies52, 53 (#NCT00381797, #NCT01217437).

2.9 Topoisomerase inhibitors

Topoisomerase I and II are enzymes involved in DNA replication, cellular senescence and apoptosis. Irinotecan, topotecan and camptothecan are directed against these enzymes.

Topotecan and irinotecan have the same pharmacodynamics, but different pharmacokinetics; topotecan easily crosses the BBB, demonstrating, in many stand-alone clinical trials, (#NCT00112619, #NCT00005811) or also in combination with chemotherapy (#NCT02684071), increased survival.54-56

Indimitecan and Indotecan (LMP 400), both topoisomerase inhibitors, are still under evaluation.

3 Adoptive Immunotherapies

3.1 Checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs)

The success of CPIs to augment the immunological response against many solid tumors has generated interest in the applicability also for MBs, especially in the advanced stages.

Two anti-PD-1 agents, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are under evaluation for pediatric tumors. An ongoing phase I clinical trial is assessing the safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab in progressive and recurrent tumors, including MBs (#NCT02359565); another phase II trial is evaluating the efficacy of nivolumab in pediatric brain tumors (#NCT03173950).

The B7 homolog 3 (B7-H3), an antibody immune checkpoint inhibitor directed against T-cells, has been tested in a phase I trial in combination with radiotherapy, and for advanced metastatic MBs (#NCT00089245).

APX005M, an IgG monoclonal antibody directed at CD40, has been designed to stimulate the anti-tumor immune response. It has been tested in a phase I pediatric trial (#NCT03389802) in patients with recurrent and refractory primary malignant brain tumors and has also shown an excellent success rate in combination with nivolumab.

Indoleamine 2.3-dioxygenase (IDO) is an enzyme, overexpressed in many tumors, which regulates the tumor microenvironment and enhances immune escape decreasing T-reg activity. Indoximod, an IDO inhibitor, has been studied in two different phase I/ II pediatric trials with concomitant use of temozolomide (#NCT02502708, #NCT04049669).

3.2 Engineered CAR-T and NK cells

Engineered T-cells expressing artificial chimeric antigen receptors (CAR-T) are largely employed in neuro-oncology, posing challenges in finding tumor-associated antigens.

HER2 is usually overexpressed in MBs, and preclinical studies are testing the efficacy of HER2-CAR T-cells in mouse models54.

At the Seattle Children’s Hospital the BrainChild-01 phase I trial was conducted, which tested autologous CD4+/CD8+ T-cells lentivirally transduced to express HER2 and EGFRt (truncated form of EGFR) CARs, delivered by catheter in the tumor resection cavity or ventricular system, for recurrent or refractory HER2+ CNS tumors (#NCT03500991).

Another phase I trial proved the EGFR806 and EGFRt CAR T-cells for patients with recurrent/refractory EGFR+CNS tumors (#NCT03638167).

NK cells are fundamental in immune response, recognizing tumor cells without specific antigens. In an ongoing phase I clinical trial, propagated ex vivo with artificial antigen-presenting cells, NK cells have been administered directly into the ventricles in recurrent and refractory malignant posterior fossa tumors (#NCT02271711).

3.3 Oncolytic viruses

The main advantages of oncolytic viruses (OVs)-based immunotherapy consist in the selective replication within the tumor cells, inducing lysis of tumor cells and releasing neoantigens to the tumor microenvironment, thus activating the immune cascade.

For pediatric brain tumors, several types of OVs have been investigated.

Genetically engineered herpes simplex viruses (HSV), rRp450, G207 and M002 revealed antitumor activity and prolonged survival in mice xenografts of aggressive MBs cells.57

A recruiting phase I trial evaluated the engineered HSV G207 for children with refractory cerebellar brain tumors58 (#NCT03911388).

The measles virus expressing thyroidal sodium iodide symporter (MV-NIS) has been engineered in an ongoing phase I study testing its efficacy in pediatric recurrent MBs. MV-NIS is administered intrathecally59 (#NCT02962167).

The highly attenuated recombinant polio/rhinovirus (PVSRIPO) recognizes the CD155 receptor expressed in the MBs tumor cell microenvironment. It is used in a phase I pediatric trial, administered by the intracerebral catheter for WHO grade III and IV malignant brain tumors (#NCT03043391).

Phase I of the PRiME clinical trial evaluates a two-component cytomegalovirus specific multi-epitope peptide vaccine (PEP-CMV), administered after temozolomide, in pediatric patients with recurrent MBs and high-grade gliomas (#NCT03299309).

4 Clinical Trials on MB Therapies

Out of 51 clinical trials, 55% were phase I, 33% phase II and 12% phase I/II (Graph 1). Target therapies and adoptive immunotherapies were tested in 71% and 29% of them, respectively (Graph 2). Table 3 summarizes the clinical trials on new therapeutic strategies for MBs (Table 3).

Graph 1.

Pie graph showing the distribution of the clinical trials according to the study phase.

Graph 2.

Pie graph showing the distribution of the clinical trials according to types of therapy.

Table 3.

Clinical trials on new therapeutic strategies for MBs

| # | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Title | Status | Study Phase | Conditions | Interventions | # of Patients Enrollment | Locations |

| 1 | NCT00822458 | GDC-0449 in Treating Young Patients With Medulloblastoma That is Recurrent or Did Not Respond to Previous Treatment | Completed | I | Recurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | Vismodegib | 34 | USA |

| 2 | NCT03434262 | SJDAWN: St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Phase 1 Study Evaluating Molecularly-Driven Doublet Therapies for Children and Young Adults With Recurrent Brain Tumors | Recruiting | I | Central Nervous System Tumors | Gemcitabina, Ribociclib, Sonidegib, Trametinib, Filgrastim | 108 | USA |

| 3 | NCT01878617 | A Clinical and Molecular Risk-Directed Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Medulloblastoma | Recruiting | II | Medulloblastoma | Vismodegib, Chemiotherapy, Radiation | 625 | USA |

| 4 | NCT01601184 | Study of Vismodegib in Combination With Temozolomide Versus Temozolomide Alone in Patients With Medulloblastomas With an Activation of the Sonic Hedgehog Pathway | Terminated | I, II | "MedulloblastomaActivation of the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Pathway" | Vismodegib, Temozolomide | 24 | UK, SW, IT, FR |

| 5 | NCT00939484 | Vismodegib in Treating Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Medulloblastoma | Completed | II | Adult Medulloblastoma | Vismodegib | 31 | USA |

| 6 | NCT01239316 | Vismodegib in Treating Younger Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Medulloblastoma | Completed | II | Recurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | Vismodegib | 12 | USA |

| 7 | NCT03734913 | A Phase 1 Study of ZSP1602 in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors | Recruiting | I | Basal Cell Carcinoma | ZSP1602 | 65 | CN |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma of Esophagogastric Junction | ||||||||

| Small Cell Lung Cancer | ||||||||

| Neuroendocrine Neoplasm | ||||||||

| Glioblastoma | ||||||||

| 8 | NCT01708174 | A Phase II Study of Oral LDE225 in Patients With Hedge-Hog (Hh)-Pathway Activated Relapsed Medulloblastoma (MB) | Completed | II | Medulloblastoma | Sonidegib, Temozolomide | 22 | USA |

| 9 | NCT01208831 | An East Asian Study of LDE225 (Sonidegib) | Completed | I | Advanced Solid Tumor Cancers | Sonidegib | 45 | TW |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Basal Cell Carcinoma | ||||||||

| 10 | NCT00880308 | Dose Finding and Safety of Oral LDE225 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors | Completed | I | S | Sonidegib | 103 | UK, ES |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Basal Cell Carcinoma | ||||||||

| 11 | NCT01125800 | A Phase I Dose Finding and Safety Study of Oral LDE225 in Children and a Phase II Portion to Assess Preliminary Efficacy in Recurrent or Refractory MB | Completed | I, II | Medulloblastoma | Sonidegib | 76 | USA |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||||||||

| Neuroblastoma | ||||||||

| Hepatoblastoma | ||||||||

| Glioma | ||||||||

| Astrocytoma | ||||||||

| 12 | NCT03936465 | Study of the Bromodomain (BRD) and Extra-Terminal Domain (BET) Inhibitor BMS-986158 in Pediatric Cancer | Recruiting | I | Solid Tumor, Childhood | BMS-986158 | 34 | USA |

| Lymphoma | ||||||||

| Brain Tumor, Pediatric | ||||||||

| 13 | NCT00095940 | Lapatinib in Treating Young Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Central Nervous System Tumors | Completed | I, II | Central Nervous System Tumors | Lapatinib, Surgery | 52 | USA |

| 14 | NCT00788125 | Dasatinib, Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, and Etoposide in Treating Young Patients With Metastatic or Recurrent Malignant Solid Tumors | Active, not recruiting | I, II | Central Nervous System Tumors | Carboplatin, Dasatinib, Etoposide, Ifosfamide | 143 | USA |

| 15 | NCT00077454 | Erlotinib and Temozolomide in Treating Young Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Solid Tumors | Completed | I | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Erlotinib, Temozolomide | 95 | USA |

| 16 | NCT00360854 | Erlotinib Alone or in Combination With Radiation Therapy in Treating Young Patients With Refractory or Relapsed Malignant Brain Tumors or Newly Diagnosed Brain Stem Glioma | Unknown | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | Erlotinib, Radiotherapy | 48 | UK, IE |

| 17 | NCT03598244 | Volitinib in Treating Participants With Recurrent or Refractory Primary CNS Tumors | Recruiting | I | Primary Central Nervous System Neoplasm | Savolitinib | 36 | USA |

| Recurrent/Refractory Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent/Refractory Malignant Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent/Refractory Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 18 | NCT03210714 | Erdafitinib in Treating Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Tumors, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, or Histiocytic Disorders With FGFR Mutations (A Pediatric MATCH Treatment Trial) | Recruiting | II | Advanced Malignant Solid Neoplasm | Erdafitinib | 49 | USA |

| Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | ||||||||

| Childhood Hematologic Neoplasms | ||||||||

| 19 | NCT03893487 | Fimepinostat in Treating Brain Tumors in Children and Young Adults | Recruiting | I | Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | Fimepinostat, Surgery | 30 | USA |

| Recurrent Anaplastic Astrocytoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Glioblastoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Malignant Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 20 | NCT03213678 | PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor LY3023414 in Treating Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Tumors, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, or Histiocytic Disorders With TSC or PI3K/MTOR Mutations (A Pediatric MATCH Treatment Trial) | Recruiting | II | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Samotolisib | 144 | USA |

| Childhood Hematologic Neoplasms | ||||||||

| 21 | NCT03155620 | Targeted Therapy Directed by Genetic Testing in Treating Pediatric Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Tumors, Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas, or Histiocytic Disorders (The Pediatric MATCH Screening Trial)” | Recruiting | II | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Ensartinib, Erdafitinib, Larotrectinib, Olaparib, Palbociclib, Samotolisib, Selpercatinib, Selumetinib Sulfate, Tazemetostat, Tipifarnib, Ulixertinib, Vemurafenib | 1500 | USA |

| Childhood Hematologic Neoplasms | ||||||||

| 22 | NCT03526250 | Palbociclib in Treating Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Rb Positive Advanced Solid Tumors, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, or Histiocytic Disorders With Activating Alterations in Cell Cycle Genes (A Pediatric MATCH Treatment Trial) | Recruiting | II | Advanced Malignant Solid Neoplasm | Palbociclib | 49 | USA |

| Childhood Neoplasms | ||||||||

| 23 | NCT03709680 | Study Of Palbociclib Combined With Chemotherapy In Pediatric Patients With Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors | Recruiting | I | Ewing Sarcoma | Palbociclib, Temozolomide, Irinotecan | 100 | USA |

| Rhabdoid Tumor, Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||||||||

| Neuroblastoma | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | ||||||||

| 24 | NCT02255461 | Palbociclib Isethionate in Treating Younger Patients With Recurrent, Progressive, or Refractory Central Nervous System Tumors | Terminated | I | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Palbociclib | 35 | USA |

| 25 | NCT03387020 | Ribociclib and Everolimus in Treating Children With Recurrent or Refractory Malignant Brain Tumors | Recruiting | I | Central Nervous System Embryonal Tumors | Ribociclib, Everolimus | 45 | USA |

| Malignant Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumor | ||||||||

| Recurrent Childhood Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent/Refractory Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 26 | NCT01977677 | Plerixafor After Radiation Therapy and Temozolomide in Treating Patients With Newly Diagnosed High Grade Glioma | Completed | I, II | Adult Ependymoblastoma | Temozolomide, Plerixafor, Radiotherapy | 30 | USA |

| Adult Giant Cell Glioblastoma | ||||||||

| Adult Glioma, Glioblastoma, Gliosarcoma | ||||||||

| Adult Pineoblastoma | ||||||||

| Adult Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Adult Supratentorial Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET) | ||||||||

| Adult Oligodendroglial Tumors | ||||||||

| 27 | NCT00381797 | Bevacizumab and Irinotecan in Treating Young Patients With Recurrent, Progressive, or Refractory Glioma, Medulloblastoma, Ependymoma, or Low Grade Glioma | Completed | II | Childhood Cerebral Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Bevacizumab, Fludeoxyglucose F-18, Irinotecan Hydrochloride | 97 | USA |

| Childhood Oligodendroglioma | ||||||||

| Childhood Spinal Cord Neoplasm | ||||||||

| Recurrent Childhood Brain Stem Glioma Recurrent Childhood EpendymomaRecurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Childhood Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 28 | NCT01217437 | Temozolomide and Irinotecan Hydrochloride With or Without Bevacizumab in Treating Young Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Medulloblastoma or CNS Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors | Active, not recruiting | II | Recurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | Bevacizumab, Temozolomide, Irinotecan Hydrochloride | 108 | USA |

| Recurrent Childhood Pineoblastoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Childhood Supratentorial Embryonal Tumor, Not Otherwise Specified | ||||||||

| 29 | NCT00601003 | Study of Nifurtimox to Treat Refractory or Relapsed Neuroblastoma or Medulloblastoma | Active, not recruiting | II | Neuroblastoma | Nifurtimox, Cyclophosphamide, Topotecan | 112 | USA |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 30 | NCT02684071 | Phase II Study of Intraventricular Methotrexate in Children With Recurrent or Progressive Malignant Brain Tumors" | Terminated | II | Recurrent Childhood Medulloblastoma | Intrathecal Methotrexate, Topotecan, Cyclophosphamide | 3 | USA |

| Recurrent Childhood Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Childhood Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumor | ||||||||

| Embryonal Tumors | ||||||||

| Metastatic Malignant Brain Neoplasm | ||||||||

| 31 | NCT00005811 | Topotecan Hydrochloride in Treating Children With Meningeal Cancer That Has Not Responded to Previous Treatment" | Completed | II | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Topotecan | 77 | USA |

| Childhood Hematologic Neoplasms | ||||||||

| 32 | NCT00112619 | Topotecan in Treating Young Patients With Neoplastic Meningitis Due to Leukemia, Lymphoma, or Solid Tumors | Terminated | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | Topotecan | 19 | USA |

| Primary Leukemia, Lymphoma | ||||||||

| Unspecified Childhood Solid Tumor | ||||||||

| 33 | NCT00404495 | Combination of Irinotecan and Temozolomide in Children With Brain Tumors. | Completed | II | Glioma | Irinotecan, Temozolomide | 83 | AU |

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 34 | NCT02095132 | Adavosertib and Irinotecan Hydrochloride in Treating Younger Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Solid Tumors | Recruiting | I, II | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Adavosertib, Irinotecan | 154 | USA |

| 35 | NCT00004078 | Irinotecan in Treating Children With Refractory Solid Tumors | Completed | II | Childhood Central Nervous System Tumors | Irinotecan | 181 | USA |

| 36 | NCT00138216 | Temozolomide, Vincristine, and Irinotecan in Treating Young Patients With Refractory Solid Tumors” | Completed | I | I Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | Irinotecan, Temozolomide, Vincristine | 42 | USA |

| Unspecified Childhood Solid Tumor, Protocol Specific | ||||||||

| 37 | NCT02359565 | Pembrolizumab in Treating Younger Patients With Recurrent, Progressive, or Refractory High-Grade Gliomas, Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas, Hypermutated Brain Tumors, Ependymoma or Medulloblastoma | Recruiting | I | Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency Syndrome | Pembrolizumab | 110 | USA |

| Lynch Syndrome | ||||||||

| Malignant Glioma | ||||||||

| Recurrent Brain Neoplasm | ||||||||

| Recurrent/Refractory Childhood Ependymoma and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Recurrent/Refractory Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 38 | NCT03173950 | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Nivolumab in People With Select Rare CNS Cancers | Recruiting | II | Medulloblastoma | Nivolumab | 180 | USA |

| Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Pineal RegionTumors | ||||||||

| Choroid Plexus Tumors | ||||||||

| Atypical/Malignant Meningioma | ||||||||

| 39 | NCT00089245 | Radiolabeled Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Treating Patients With Refractory, Recurrent, or Advanced CNS or Leptomeningeal Cancer | Unknown | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | Iodine I 131 monoclonal antibody 8H9 | 120 | USA |

| Sarcoma | ||||||||

| Neuroblastoma | ||||||||

| 40 | NCT03389802 | Phase I Study of APX005M in Pediatric CNS Tumors | Recruiting | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | APX005M | 45 | USA |

| 41 | NCT02502708 | Study of the IDO Pathway Inhibitor, Indoximod, and Temozolomide for Pediatric Patients With Progressive Primary Malignant Brain Tumors | Active, not recruiting | I | Glioma, Glioblastoma, Gliosarcoma | Indoximod, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy, Cyclophosphamide, Etoposide | 81 | USA |

| Malignant Brain Tumor | ||||||||

| Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | ||||||||

| Primary CNS Tumor | ||||||||

| 42 | NCT04049669 | Pediatric Trial of Indoximod With Chemotherapy and Radiation for Relapsed Brain Tumors or Newly Diagnosed DIPG" | Recruiting | II | Glioblastoma | Indoximod, Radiotherapy, Temozolomide, Cyclophosphamide, Etoposide, Lomustine | 140 | USA |

| Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | ||||||||

| 43 | NCT03500991 | HER2-specific CAR T Cell Locoregional Immunotherapy for HER2-positive Recurrent/Refractory Pediatric CNS Tumors | Recruiting | I | Central Nervous System Tumor, Pediatric | HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell | 36 | USA |

| 44 | NCT03638167 | EGFR806-specific CAR T Cell Locoregional Immunotherapy for EGFR-positive Recurrent or Refractory Pediatric CNS Tumors | Recruiting | I | Central Nervous System Tumor, Pediatric | EGFR806-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell | 36 | USA |

| 45 | NCT02271711 | Expanded Natural Killer Cell Infusion in Treating Younger Patients With Recurrent/Refractory Brain Tumors | Active, not recruiting | I | Recurrent Medulloblastoma | Natural Killer Cell Therapy | 12 | USA |

| Recurrent Ependymoma | ||||||||

| 46 | NCT04270461 | NKG2D-based CAR T-cells Immunotherapy for Patient With r/r NKG2DL+ Solid Tumors | Not yet Recruiting | I | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | NKG2D-based CAR T-cells | 10 | China |

| Colon Cancer | ||||||||

| Glioblastoma | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| 47 | NCT04185038 | Study of B7-H3-Specific CAR T Cell Locoregional Immunotherapy for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma/Diffuse Midline Glioma and Recurrent or Refractory Pediatric Central Nervous System Tumors | Recruiting | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | SCRI-CARB7H3(s); B7H3-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell | 70 | USA |

| 48 | NCT03911388 | HSV G207 in Children With Recurrent or Refractory Cerebellar Brain Tumors | Recruiting | I | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | HSV G207 | 15 | USA |

| 49 | NCT02962167 | Modified Measles Virus (MV-NIS) for Children and Young Adults With Recurrent Medulloblastoma or Recurrent ATRT | Recruiting | I | Medulloblastoma, Childhood, Recurrent | Modified Measles Virus | 46 | USA |

| Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumor | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma Recurrent | ||||||||

| 50 | NCT03043391 | Phase 1b Study PVSRIPO for Recurrent Malignant Glioma in Children | Recruiting | I | Malignant Glioma, Glioblastoma, Gliosarcoma | Polio/Rhinovirus Recombinant (PVSRIPO) | 12 | USA |

| Anaplastic Astrocytoma, Oligoastrocytoma, Oligodendroglioma | ||||||||

| Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumor | ||||||||

| Medulloblastoma | ||||||||

| Ependymoma | ||||||||

| Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma | ||||||||

| Embryonal Tumor of Brain | ||||||||

| 51 | NCT03299309 | PEP-CMV in Recurrent MEdulloblastoma/Malignant Glioma | Recruiting | I | Recurrent Medulloblastoma | PEP-CMV | 30 | USA |

| Recurrent Brain Tumor | ||||||||

| Childhood Malignant Glioma |

AU: Australia; IE: Ireland; ES: Spain; CN: Cina; FR: France; IT: Italy; SW: Switzerland; TW: Taiwan; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America

Discussion

Despite the refinements in neurosurgical techniques, concerning both neuro-oncology and other fields, present standard of care for MBs, including maximal surgical resection followed by adjuvant radio and chemotherapy protocols, fails to recognize heterogeneity within MB subtypes, resulting in low efficacy, high recurrence rate and risk of long-term toxicity.60, 61

Challenges come from the need for distinguishing molecular subgroups and identifying patients for whom a personalized treatment approach would be recommended.

1 Molecular Subgroup-Based Tailored Strategies

1.1 WNT-MBs

WNT signaling was the first identified. However, no drugs directed against this pathway have been approved as an alternative to standard therapy.

Only two molecules have been tested, namely norcantharidin, which blocks the WNT pathway, and lithium chloride, which stabilizes β-catenin and reduces MB progression.62-65

The reason for the lack of success in inhibiting the WNT pathway lies in the fact that it seems to be involved in vascular dysfunction and BBB disrupting, therefore increasing the penetration of drugs. Further issues are the various developmental processes, including physiological tissue regeneration and bone growth.66, 67 As a matter of fact, inhibition would result not only in reduced chemosensitivity, but also would have long-term complications. No further targeted therapies have been developed, and clinical trials have focused especially on decreasing the doses of radio-chemotherapy for low- or standard-risk WNT-MBs (#NCT01878617, #NCT02724579).

1.2 SHH-MBs

Among the target therapies, agents directed against the SHH pathway gave the most promising results. Most SHH-MB patients harbor PTCH1 or SMO mutations. SMO inhibitors, primarily vismodegib, demonstrated their efficacy in several trials.68

Mutations of the SMO downstream pathway, such as SUFU or GLI1, make the SMO inhibitors ineffective. Several clinical trials increased the development of drugs directed against BET, SUFU, c-MET, CDK4/ 6 (ribociclib) and MET (foretinib) inhibitors, used in combination for overcoming therapeutic resistance.

In SMO-mutated MBs, PI3K signaling is usually increased, and the combined use of SHH-inhibitors with PI3K blockers also has a rationale.69, 70 Finally, planning tailored therapies, made with a combination of HH inhibitors and TKIs, proteasome and chemokine inhibitors, may present a future opportunity in the management of this tumor group.

1.3 Group 3

The dismal prognosis occurring in Group 3 MBs, made an urgent development of targeted therapies necessary.53 The increased expression level of the MYC gene, found in about 10-20 % of Group 3 patients, confers a very poor outcome. FDA approved pemetrexed and gemcitabine along with standard chemotherapy for this category.

Many clinical trials also demonstrated the efficacy of palbociclib, CDK4/6 inhibitor, PI3K inhibitor, BRD4 inhibitor and anti-vascularization therapies in monotherapy or in association with standard treatment for MBs of Group 3.

Alternative strategies, applicable to this subtype, include immunotherapies, mainly those that exploit engineered T and NK cells.

1.4 Group 4

The genomic heterogeneity of Group 4 is not clearly understood, and this constitutes the major limit in the development of target therapies.

It has been mainly immunotherapies, with CPIs, engineered T and NK cells and OVs that have been tested, with results that are still quite limited.

For those patients with relative activation of NOTCH signaling, a novel therapeutic opportunity is the administration of MK-0752 and RO4929097, both inhibitors of transcription of the NOTCH genes.71

2 Ongoing Challenges and Future Prospects

The main limitations in the development of an effective MB tailored approach are primarily the overcoming of the BBB, the tumor microenvironment and the tumor stem cell response.

The route of drug administration is still an issue in the management of these therapies.

In 2016, Phoenix et al. highlighted that the gene expression patterns applied to tumor subtypes determines the configuration of the BBB, which avoids drug penetration and reduces chemoresponsiveness.64 WBT-MBs seem to have a better prognosis because of the presence of fenestrated vessels facilitating the penetration of drugs.64

Concerning strategies aimed at overcoming the BBB, possible routes of administration are intrathecal, stereotactic or endoscopic. These routes make it possible to deliver drugs directly into the tumor cavity, and as for other neurological and neurosurgical pathologies, they have the advantage of minimal invasiveness.72, 73

A valuable alternative comes from nanotechnology, which uses polymeric nanomedicines that are able to easily cross the BBB.74, 75

In addition, several studies have highlighted the presence of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in malignant brain tumors, which have self-renewing capabilities. The high incidence of dissemination and recurrence associated with MB is mainly attributable to the presence of CSCs. They have been reported to also be responsible for therapeutic resistance.76, 77 A further ongoing therapeutic approach targets the MB-CSCs, with agents directed at targeting specific pathways, such as CD133, SHH, PI3K/AKT, Stat3, and NOTCH.78-80

Yu et al. tested the Seneca Valley virus-001 (SVV-001) which can infect and destroy the CSCs, express CD133, and results in increased survival.81

However, the current amount of knowledge on MB-CSCs is still not sufficient for bedside application.

Conclusion

Advanced genetic studies resulted in the identification of prognostic factors of MBs, which have been translated into a risk stratification and an updated classification. The new genetic subgrouping provides the possibility for refining MB treatment strategies and developing novel molecular-guided clinical interventions.

Target agents directed against SHH, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and TKIs have been tested with favorable results, especially in SHH-MBs, whereas adoptive immunotherapies have been proposed for recurrent or refractory MBs.

The high genetic heterogeneity, especially of Group 3 and 4 MBs, the presence of CSCs and the BBB, are all responsible for chemoresistance.

Tailored therapies and combined chemotherapy approaches need to be further validated.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Giorgia Di Giusto, Engineer, for her invaluable technical support during data collection and analysis.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Smoll NR, Drummond KJ. The incidence of medulloblastomas and primitive neurectodermal tumours in adults and children. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(11):1541–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramaswamy V, Remke M, Bouffet E, et al. Risk stratification of childhood medulloblastoma in the molecular era: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):821–831. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1569-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1569-6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pui CH, Gajjar AJ, Kane JR, Qaddoumi IA, Pappo AS. Challenging issues in pediatric oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(9):540–549. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.95. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salloum R, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Late Morbidity and Mortality Among Medulloblastoma Survivors Diagnosed Across Three Decades: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(9):731–740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00969. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.00969 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ning MS, Perkins SM, Dewees T, Shinohara ET. Evidence of high mortality in long term survivors of childhood medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2015;122(2):321–327. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1712-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1712-y . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual-Castroviejo I, Lopez-Pereira P, Savasta S, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Lago CM, Cisternino M. Neurofibromatosis type 1 with external genitalia involvement presentation of 4 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(11):1998–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.01.074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.01.074 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savasta S, Chiapedi S, Perrini S, Tognato E, Corsano L, Chiara A. Pai syndrome: a further report of a case with bifid nose, lipoma, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24(6):773–776. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0613-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-008-0613-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salpietro V, Mankad K, Kinali M, et al. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension and the underlying endocrine-metabolic dysfunction: a pilot study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27(1-2):107–115. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0156. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2013-0156 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nosadini M, Granata T, Matricardi S, et al. Relapse risk factors in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(9):1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14267. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14267 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng CY, Shetty R, Sekhar LN. Microsurgical Resection of a Large Intraventricular Trigonal Tumor: 3-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;15(6):E92–E93. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy068. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy068 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palumbo P, Lombardi F, Siragusa G, et al. Involvement of NOS2 Activity on Human Glioma Cell Growth, Clonogenic Potential, and Neurosphere Generation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms19092801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19092801 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luzzi S, Crovace AM, Del Maestro M, et al. The cell-based approach in neurosurgery: ongoing trends and future perspectives. Heliyon. 2019;5(11):e02818. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02818 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luzzi S, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, et al. Anterolateral Approach for Retrostyloid Superior Parapharyngeal Space Schwannomas Involving the Jugular Foramen Area: A 20-Year Experience. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e40–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spena G, Roca E, Guerrini F, et al. Risk factors for intraoperative stimulation-related seizures during awake surgery: an analysis of 109 consecutive patients. J Neurooncol. 2019;145(2):295–300. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03295-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03295-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonosante A, Brandolini L, d’Angelo M, et al. Autocrine CXCL8-dependent invasiveness triggers modulation of actin cytoskeletal network and cell dynamics. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(2):1928–1951. doi: 10.18632/aging.102733. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102733 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(4):465–472. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Northcott PA, Buchhalter I, Morrissy AS, et al. The whole-genome landscape of medulloblastoma subtypes. Nature. 2017;547(7663):311–317. doi: 10.1038/nature22973. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22973 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northcott PA, Jones DT, Kool M, et al. Medulloblastomics: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(12):818–834. doi: 10.1038/nrc3410. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3410 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parisi P, Vanacore N, Belcastro V, et al. Clinical guidelines in pediatric headache: evaluation of quality using the AGREE II instrument. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:57. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-57 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foiadelli T, Piccorossi A, Sacchi L, et al. Clinical characteristics of headache in Italian adolescents aged 11-16 years: a cross-sectional questionnaire school-based study. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0486-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0486-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garone G, Reale A, Vanacore N, et al. Acute ataxia in paediatric emergency departments: a multicentre Italian study. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(8):768–774. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315487. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315487 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kool M, Korshunov A, Remke M, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis of transcriptome, genetic aberrations, and clinical data of WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(4):473–484. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0958-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-012-0958-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson MC, Fuller C, Hogg TL, et al. Genomics identifies medulloblastoma subgroups that are enriched for specific genetic alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(12):1924–1931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4974. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4974 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Witt H, et al. Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1408–1414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4324. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4324 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbertson RJ. Medulloblastoma: signalling a change in treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(4):209–218. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01424-X. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01424-X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DT, Jager N, Kool M, et al. Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488(7409):100–105. doi: 10.1038/nature11284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11284 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, et al. Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations. Nature. 2012;488(7409):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11329. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11329 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson G, Parker M, Kranenburg TA, et al. Novel mutations target distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488(7409):43–48. doi: 10.1038/nature11213. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11213 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Haas T, Hasselt N, Troost D, et al. Molecular risk stratification of medulloblastoma patients based on immunohistochemical analysis of MYC, LDHB, and CCNB1 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4154–4160. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4159. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4159 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park TS, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP, Becker LE. Medulloblastoma: clinical presentation and management. Experience at the hospital for sick children, toronto, 1950–1980. J Neurosurg. 1983;58(4):543–552. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.4.0543. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1983.58.4.0543 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gajjar AJ, Robinson GW. Medulloblastoma-translating discoveries from the bench to the bedside. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(12):714–722. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.181. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.181 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northcott PA, Shih DJ, Peacock J, et al. Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes. Nature. 2012;488(7409):49–56. doi: 10.1038/nature11327. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11327 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northcott PA, Hielscher T, Dubuc A, et al. Pediatric and adult sonic hedgehog medulloblastomas are clinically and molecularly distinct. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(2):231–240. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0846-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-011-0846-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kool M, Jones DT, Jager N, et al. Genome sequencing of SHH medulloblastoma predicts genotype-related response to smoothened inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.004 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallahan AR, Pritchard JI, Hansen S, et al. The SmoA1 mouse model reveals that notch signaling is critical for the growth and survival of sonic hedgehog-induced medulloblastomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64(21):7794–7800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1813. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1813 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayrault O, Zhao H, Zindy F, Qu C, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Atoh1 inhibits neuronal differentiation and collaborates with Gli1 to generate medulloblastoma-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5618–5627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3740. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3740 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellison DW, Dalton J, Kocak M, et al. Medulloblastoma: clinicopathological correlates of SHH, WNT, and non-SHH/WNT molecular subgroups. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(3):381–396. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0800-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-011-0800-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rausch T, Jones DT, Zapatka M, et al. Genome sequencing of pediatric medulloblastoma links catastrophic DNA rearrangements with TP53 mutations. Cell. 2012;148(1-2):59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.013 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson P, Tong Y, Robinson G, et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1095–1099. doi: 10.1038/nature09587. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09587 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skowron P, Ramaswamy V, Taylor MD. Genetic and molecular alterations across medulloblastoma subgroups. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015;93(10):1075–1084. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1333-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-015-1333-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar R, Liu APY, Northcott PA. Medulloblastoma genomics in the modern molecular era. Brain Pathol. 2019 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12804. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12804 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, et al. Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;25(10):2524–2533. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166. https://doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berman DM, Karhadkar SS, Hallahan AR, et al. Medulloblastoma growth inhibition by hedgehog pathway blockade. Science. 2002;297(5586):1559–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.1073733. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1073733 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menyhart O, Giangaspero F, Gyorffy B. Molecular markers and potential therapeutic targets in non-WNT/non-SHH (group 3 and group 4) medulloblastomas. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0712-y. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-019-0712-y . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman S, Sowa ME, Ottinger M, et al. The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(13):2641–2652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01341-10. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01341-10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKeown MR, Bradner JE. Therapeutic strategies to inhibit MYC. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014266. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a014266 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wojtalla A, Salm F, Christiansen DG, et al. Novel agents targeting the IGF-1R/PI3K pathway impair cell proliferation and survival in subsets of medulloblastoma and neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047109 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhukova N, Ramaswamy V, Remke M, et al. Subgroup-specific prognostic implications of TP53 mutation in medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2927–2935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5052. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5052 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunkele A, De Preter K, Heukamp L, et al. Pharmacological activation of the p53 pathway by nutlin-3 exerts anti-tumoral effects in medulloblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(7):859–869. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos115. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos115 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sengupta R, Dubuc A, Ward S, et al. CXCR4 activation defines a new subgroup of Sonic hedgehog-driven medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(1):122–132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1701. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1701 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguilera D, Mazewski C, Fangusaro J, et al. Response to bevacizumab, irinotecan, and temozolomide in children with relapsed medulloblastoma: a multi-institutional experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(4):589–596. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-2013-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-012-2013-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson EM, Keir ST, Venkatraman T, et al. The role of angiogenesis in Group 3 medulloblastoma pathogenesis and survival. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(9):1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox033. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox033 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nellan A, Rota C, Majzner R, et al. Durable regression of Medulloblastoma after regional and intravenous delivery of anti-HER2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. J Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0340-z. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-018-0340-z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saylors RL, 3rd, Stine KC, Sullivan J, et al. Cyclophosphamide plus topotecan in children with recurrent or refractory solid tumors: a Pediatric Oncology Group phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(15):3463–3469. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3463. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3463 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff JE, Westphal S, Molenkamp G, et al. Treatment of paediatric pontine glioma with oral trophosphamide and etoposide. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(9):945–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600552. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600552 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedman GK, Moore BP, Nan L, et al. Pediatric medulloblastoma xenografts including molecular subgroup 3 and CD133+ and CD15+ cells are sensitive to killing by oncolytic herpes simplex viruses. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(2):227–235. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov123. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov123 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Markert JM, Razdan SN, Kuo HC, et al. A phase 1 trial of oncolytic HSV-1, G207, given in combination with radiation for recurrent GBM demonstrates safety and radiographic responses. Mol Ther. 2014;22(5):1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.22. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2014.22 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutzen B, Bid HK, Houghton PJ, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with oncolytic measles viruses expressing the angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin and angiostatin. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-206. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-206 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luzzi S, Elia A, Del Maestro M, et al. Indication, Timing, and Surgical Treatment of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Systematic Review and Proposal of a Management Algorithm. World Neurosurg. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Millimaggi DF, Norcia VD, Luzzi S, Alfiero T, Galzio RJ, Ricci A. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion with Percutaneous Bilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation for Lumbosacral Spine Degenerative Diseases. A Retrospective Database of 40 Consecutive Cases and Literature Review. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28(3):454–461. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cimmino F, Scoppettuolo MN, Carotenuto M, et al. Norcantharidin impairs medulloblastoma growth by inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Neurooncol. 2012;106(1):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0645-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0645-y . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zinke J, Schneider FT, Harter PN, et al. beta-Catenin-Gli1 interaction regulates proliferation and tumor growth in medulloblastoma. Mol. Cancer. 2015;14:17. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0294-4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-015-0294-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phoenix TN, Patmore DM, Boop S, et al. Medulloblastoma Genotype Dictates Blood Brain Barrier Phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(4):508–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Houschyar KS, Tapking C, Borrelli MR, et al. Wnt Pathway in Bone Repair and Regeneration - What Do We Know So Far. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:170. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2018.00170 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galluzzi L, Spranger S, Fuchs E, Lopez-Soto A. WNT Signaling in Cancer Immunosurveillance. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(1):44–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.08.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2018.08.005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remke M, Hielscher T, Korshunov A, et al. FSTL5 is a marker of poor prognosis in non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(29):3852–3861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2798. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2798 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson GW, Orr BA, Wu G, et al. Vismodegib Exerts Targeted Efficacy Against Recurrent Sonic Hedgehog-Subgroup Medulloblastoma: Results From Phase II Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Studies PBTC-025B and PBTC-032. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2646–2654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.1591. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.1591 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yauch RL, Dijkgraaf GJ, Alicke B, et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 2009;326(5952):572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1179386 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Metcalfe C, Alicke B, Crow A, et al. PTEN loss mitigates the response of medulloblastoma to Hedgehog pathway inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013;73(23):7034–7042. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1222. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1222 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kahn SA, Wang X, Nitta RT, et al. Notch1 regulates the initiation of metastasis and self-renewal of Group 3 medulloblastoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4121. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06564-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06564-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luzzi S, Zoia C, Rampini AD, et al. Lateral Transorbital Neuroendoscopic Approach for Intraconal Meningioma of the Orbital Apex: Technical Nuances and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.152 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arnaout MM, Luzzi S, Galzio R, Aziz K. Supraorbital keyhole approach: Pure endoscopic and endoscope-assisted perspective. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;189:105623. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Catanzaro G, Curcio M, Cirillo G, et al. Albumin nanoparticles for glutathione-responsive release of cisplatin: New opportunities for medulloblastoma. Int J Pharm. 2017;517(1-2):168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.12.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.12.017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao H, Zhang S, Cao S, Yang Z, Pang Z, Jiang X. Angiopep-2 and activatable cell-penetrating peptide dual-functionalized nanoparticles for systemic glioma-targeting delivery. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(8):2755–2763. doi: 10.1021/mp500113p. https://doi.org/10.1021/mp500113p . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schuller U, Heine VM, Mao J, et al. Acquisition of granule neuron precursor identity is a critical determinant of progenitor cell competence to form Shh-induced medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang GH, Xu QF, Cui YH, Li N, Bian XW, Lv SQ. Medulloblastoma stem cells: Promising targets in medulloblastoma therapy. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(5):583–589. doi: 10.1111/cas.12925. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12925 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ehrhardt M, Craveiro RB, Holst MI, Pietsch T, Dilloo D. The PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 displays promising in vitro and in vivo efficacy for targeted medulloblastoma therapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6(2):802–813. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2742. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2742 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yoshida GJ, Saya H. Therapeutic strategies targeting cancer stem cells. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(1):5–11. doi: 10.1111/cas.12817. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12817 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Islam F, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AK. Translational potential of cancer stem cells: A review of the detection of cancer stem cells and their roles in cancer recurrence and cancer treatment. Exp Cell Res. 2015;335(1):135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.04.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.04.018 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu L, Baxter PA, Zhao X, et al. A single intravenous injection of oncolytic picornavirus SVV-001 eliminates medulloblastomas in primary tumor-based orthotopic xenograft mouse models. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(1):14–27. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq148. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noq148 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shih DJ, Northcott PA, Remke M, et al. Cytogenetic prognostication within medulloblastoma subgroups. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(9):886–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9539. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.50.9539 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]