Abstract

Background:

The tailored targeting of specific oncogenes represents a new frontier in the treatment of high-grade glioma in the pursuit of innovative and personalized approaches. The present study consists in a wide-ranging overview of the target therapies and related translational challenges in neuro-oncology.

Methods:

A review of the literature on PubMed/MEDLINE on recent advances concerning the target therapies for treatment of central nervous system malignancies was carried out. In the Medical Subject Headings, the terms “Target Therapy”, “Target drug” and “Tailored Therapy” were combined with the terms “High-grade gliomas”, “Malignant brain tumor” and “Glioblastoma”. Articles published in the last five years were further sorted, based on the best match and relevance. The ClinicalTrials.gov website was used as a source of the main trials, where the search terms were “Central Nervous System Tumor”, “Malignant Brain Tumor”, “Brain Cancer”, “Brain Neoplasms” and “High-grade gliomas”.

Results:

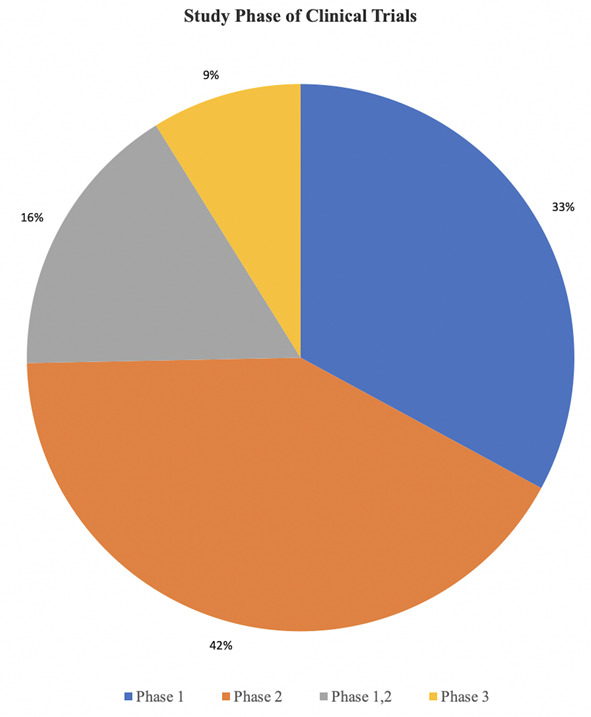

A total of 137 relevant articles and 79 trials were selected. Target therapies entailed inhibitors of tyrosine kinases, PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, farnesyl transferase enzymes, p53 and pRB proteins, isocitrate dehydrogenases, histone deacetylases, integrins and proteasome complexes. The clinical trials mostly involved combined approaches. They were phase I, II, I/II and III in 33%, 42%, 16%, and 9% of the cases, respectively.

Conclusion:

Tyrosine kinase and angiogenesis inhibitors, in combination with standard of care, have shown most evidence of the effectiveness in glioblastoma. Resistance remains an issue. A deeper understanding of the molecular pathways involved in gliomagenesis is the key aspect on which the translational research is focusing, in order to optimize the target therapies of newly diagnosed and recurrent brain gliomas. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Malignant Brain Tumors, Neuro-Oncology, Target Therapy, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Background

High-grade gliomas, with glioblastoma (GBM) being the progenitor, are the most lethal primary brain tumors of all because of the certainty of recurrence and mortality.1-4 As a matter of fact, the median overall survival is no longer than 15 months, despite current multimodality treatment including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.5, 6

The significant resistance of GBM to therapy is related to the heterogeneous genetic landscape of the tumor. High-grade gliomas harbor recurrent molecular abnormalities which are involved in the maintenance of the cell’s cycle and growth, the tumor microenvironment, pathological angiogenesis, DNA repair and apoptosis.7-10

Advances in genetics and the studies of epigenetics in many pathologies affecting the central nervous system (CNS) have allowed the molecular characterization, as well as the identification of the anomalies in the cellular signaling pathways11-14. The same insights have been of utmost importance also in neuro-oncological field, GBM first, where they led to a better understanding of tumor progression and cancer drug escape.15-20 A deeper understanding of the malignant GBM phenotype has recently improved the knowledge about the biology of cancer, which is the starting point for identifying specific biomarkers and for developing new agents for targeting specific steps in the transduction pathways of glioma cells.21 Novel tailored therapies include drugs aimed at counteracting the effects of the neoplastic genetic deregulation, pathological angiogenesis and growth factor receptors; the latter with their downstream signaling pathways.

An overview of the target therapeutic strategies and challenges in developing effective agents is reported as follows.

Methods

The search of the literature was performed on the PubMed/MEDLINE (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) search engine, with combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and text words, and on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (https://clinicaltrials.gov). The MeSH terms “Target Therapy”, “Target drug” and “Tailored Therapy” were combined with the MeSH terms “High-grade gliomas”, “Malignant brain tumor” and “Glioblastoma”. In addition to original articles, our research involved reviews and editorials. The sorting of articles was carried out focusing on the most relevant studies chosen according to titles and abstracts.

On the ClinicalTrials.gov database the texts words “Central Nervous System Tumor”, “Malignant Brain Tumor”, “Brain Cancer”, “High-grade gliomas” and “Brain Tumor” were used for the field “condition/disease”. Only trials regarding target therapies, without restrictions for localization, study phase and recruitment status were selected. Filtering included articles published in the last five years, in English or translated into English. A descriptive analysis was provided.

Results

1. Volume of the Literature

The search retrieved a total of 178 articles and 148 clinical trials. After the implementation of the exclusion criteria and removal of duplicates, 137 articles and 79 randomized and non-randomized clinical trials were collected.

About the clinical trials, 33% were phase I, 42% phase II, 16% phase I/II and 9% phase III (Graph 1). Table 1 summarizes the most relevant clinical trials on target therapies for high-grade gliomas (Table 1).

Graph 1.

Pie graph showing the distribution of the selected clinical trials according to the study phase.

Table 1.

Clinical Trials on Target Therapies for High-Grade Gliomas.

| # | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Conditions | # of Patients Enrollment | Interventions | Study Phase | Status | Locations |

| 1 | NCT00025675 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 105 | Gefitinib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 2 | NCT00016991 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 53 | Gefitinib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 3 | NCT00238797 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 36 | Gefitinib | 2 | Completed | SW |

| 4 | NCT00027625 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | n/a | Gefitinib, Temozolomide | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 5 | NCT00418327 | Malignant Brain Tumor | 48 | Erlotinib | 1 | Completed | FR |

| 6 | NCT00301418 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 11 | Erlotinib | 1, 2 | Completed | USA |

| Anaplastic Astrocytoma | |||||||

| 7 | NCT00086879 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 110 | Carmustine, Erlotinib, Temozolomide | 2 | Completed | BE, FR, IT, NL, UK |

| 8 | NCT01591577 | Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme | 50 | Lapatinib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 9 | NCT00099060 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 24 | Lapatinib | 1, 2 | Completed | CN |

| 10 | NCT02423525 | Brain Cancer | 24 | Afatinib | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 11 | NCT00977431 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 36 | Afatinib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1 | Completed | UK |

| 12 | NCT01520870 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 49 | Dacomitinib | 2 | Completed | ES |

| Brain Tumor, Recurrent | |||||||

| 13 | NCT01112527 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 58 | Dacomitinib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 14 | NCT00463073 | Malignant Gliomas | 32 | Cetuximab, Bevacizumab, Irinotecan | 2 | Completed | DK |

| 15 | NCT01800695 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 202 | Depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) , Temozolomide, Whole Brain Radiation | 1 | Completed | AU |

| 16 | NCT02573324 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 691 | Depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) , Temozolomide | 3 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| 17 | NCT04083976 | Advanced Solid Tumor | 280 | Erdafitinib | 2 | Recruiting | USA |

| 18 | NCT00049127 | Recurrent Adult Brain Neoplasm | 64 | Imatinib | 1, 2 | Completed | USA |

| 19 | NCT00613054 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 27 | Imatinib, Hydroxyurea | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 20 | NCT01331291 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 36 | Bosutinib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 21 | NCT00601614 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 119 | Temozolomide, Vandetanib | 1.2 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 22 | NCT00427440 | Advanced Malignant Glioma | 61 | AMG 102 | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 23 | NCT01632228 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 135 | Onartuzumab, Bevacizumab | 2 | Completed | CN, FR, DE, IT, ES, SW, UK , USA |

| 24 | NCT01113398 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 36 | AMG 102, Bevacizumab | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 25 | NCT01632228 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 135 | Bevacizumab, Onartuzumab | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 26 | NCT00606879 | Advanced Cancer | 46 | SGX523 | 1 | Terminated | USA |

| 27 | NCT00607399 | Advanced Cancer | 46 | SGX523 | 1 | Terminated | USA |

| 28 | NCT00784914 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 12 | Temsirolimus | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 29 | NCT00016328 | Adult Glioblastoma Multiforme | 33 | Temsirolimus | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Recurrent Adult Brain Tumor | |||||||

| 30 | NCT00047073 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 13 | Sirolimus, Surgery | 1, 2 | Completed | USA |

| 31 | NCT00672243 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 32 | Erlotinib, Sirolimus | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 32 | NCT00553150 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 122 | Everolimus, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1.2 | Completed | USA |

| 33 | NCT00085566 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 61 | Everolimus, Gefitinib | 1.2 | Completed | USA |

| Prostate Cancer | |||||||

| 34 | NCT01339052 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 65 | Buparlisib, Surgery | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 35 | NCT01473901 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 38 | Buparlisib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 36 | NCT01349660 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 88 | Buparlisib, Bevacizumab | 1, 2 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| 37 | NCT00590954 | Malignant Gliomas | 32 | Perifosine | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Brain Cancer | |||||||

| 38 | NCT00005859 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 136 | Tipifarnib | 1.2 | Completed | USA |

| 39 | NCT00049387 | Adult Giant Cell Glioblastoma | 19 | Tipifarnib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1 | Completed | USA |

| Adult Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 40 | NCT00015899 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 53 | Lonafarnib | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 41 | NCT00038493 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 23 | Temozolomide, Lonafarnib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 42 | NCT01748149 | Pediatric BRAFV600E-mutant Gliomas | 40 | Vemurafenib | 1 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| 43 | NCT02345824 | Glioblastoma | 3 | Ribociclib | 1 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| Glioma | |||||||

| 44 | NCT02896335 | Metastatic Malignant Brain Tumors | 30 | Palbociclib | 2 | Recruiting | USA |

| 45 | NCT03834740 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 24 | Ribociclib, Everolimus | 1 | Recruiting | USA |

| Brain Gliomas | |||||||

| 46 | NCT03224104 | Astrocytoma, Grade III | 81 | Zotiraciclib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1 | Recruiting | SW |

| Glioblastoma | |||||||

| 47 | NCT02942264 | Brain Tumors | 152 | Zotiraciclib, Temozolomide | 1, 2 | Recruiting | USA |

| Astrocytoma, Astroglioma | |||||||

| Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 48 | NCT02073994 | Cholangiocarcinoma | 170 | Ivosidenib | 1 | Active, not recruiting | USA, FR |

| Chondrosarcoma | |||||||

| Glioma | |||||||

| Other Advanced Solid Tumors | |||||||

| 49 | NCT02481154 | Glioma | 150 | Vorasidenib | 1 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| 50 | NCT00884741 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 637 | Bevacizumab, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 3 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Supratentorial Glioblastoma | |||||||

| 51 | NCT00731731 | Adult Glioblastoma | 125 | Temozolomide, Vorinostat | 1, 2 | Active, not recruiting | USA |

| 52 | NCT00128700 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 20 | Temozolomide, Vatalanib, Radiotherapy | 1, 2 | Completed | BE, DE, IT, NL, SW |

| 53 | NCT00108056 | Glioma | 26 | Enzastaurin | 1 | Terminated | USA |

| 54 | NCT00190723 | Malignant Glioma | 120 | Enzastaurin | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 55 | NCT00503724 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 32 | Enzastaurin | 1 | Completed | USA |

| Neuroblastoma | |||||||

| 56 | NCT00006247 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 33 | Semaxanib | 1 | Terminated | USA |

| 57 | NCT01229644 | Glioma | 10 | Crenolanib | 2 | Terminated | USA |

| 58 | NCT01393912 | Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | 55 | Crenolanib | 1 | Completed | USA |

| Progressive or Refractory High-Grade Glioma | |||||||

| 59 | NCT00305656 | Adult Giant Cell Glioblastoma | 31 | Cediranib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Adult Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Recurrent Adult Brain Tumor | |||||||

| 60 | NCT00326664 | Recurrent Glioblastoma | 55 | Cediranib | 1 | Completed | USA |

| 61 | NCT00503204 | Brain Tumor | 20 | Cediranib, Lomustine | 1 | Completed | USA, UK |

| 62 | NCT00704288 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 222 | Cabozantinib | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 63 | NCT00960492 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 26 | Cabozantinib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 64 | NCT00337207 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 55 | Bevacizumab | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 65 | NCT01740258 | Malignant Glioma | 69 | Bevacizumab, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Grade IV Malignant Glioma | |||||||

| Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 66 | NCT00271609 | Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas | 88 | Bevacizumab | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Malignant Gliomas | |||||||

| 67 | NCT01290939 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 433 | Bevacizumab, Lomustine | 3 | Unknown | USA |

| Cognition Disorders | |||||||

| Disability Evaluation | |||||||

| 68 | NCT01860638 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 296 | Bevacizumab, Lomustine | 2 | Completed | AU |

| 69 | NCT00884741 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 637 | Bevacizumab, Chemiotherapy, Radiotherapy | 3 | Completed | USA |

| GliosarcomaSupratentorial | |||||||

| 70 | NCT00943826 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 921 | Bevacizumab, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 3 | Completed | USA |

| 71 | NCT00895180 | Adult Glioblastoma Multiforme | 80 | Olaratumab, Ramucirumab | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 72 | NCT00369590 | Adult Anaplastic Astrocytoma | 58 | Aflibercept | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Adult Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma | |||||||

| Adult Giant Cell Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Recurrent Adult Brain Tumor | |||||||

| 73 | NCT00093964 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 81 | Cilengitide | 2 | Completed | USA |

| 74 | NCT00085254 | Adult Giant Cell Glioblastoma | 112 | Cilengitide, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 1, 2 | Completed | USA |

| Adult Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| 75 | NCT00689221 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 545 | Cilengitide, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 3 | Completed | USA, DE |

| 76 | NCT00165477 | Glioblastoma Multiforme | 23 | Lenalidomide, Radiotherapy | 2 | Completed | USA |

| Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Malignant Gliomas | |||||||

| 77 | NCT03345095 | Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma | 750 | Marizomib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 3 | Recruiting | AU, BE |

| 78 | NCT00006773 | Adult Anaplastic Astrocytoma | 42 | Bortezomib | 1 | Terminated | USA |

| Adult Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma | |||||||

| Adult Giant Cell Glioblastom | |||||||

| Adult Glioblastoma | |||||||

| Adult Gliosarcoma | |||||||

| Recurrent Adult Brain Tumor | |||||||

| 79 | NCT00998010 | Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors | 25 | Bortezomib, Temozolomide, Radiotherapy | 2 | Completed | USA |

AU: Austria; BE: Belgium; CA: Canada; DE: Germany; DK: Denmark; ES: Spain; FR: France; IT: Italy; NL: Netherlands; SW: Switzerland; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America

2. Classification of The Target Therapies

The target therapies are mostly categorized according to the targets, which, in their turn, include molecular alterations and oncogenic signaling. The majority of approaches are directed against signaling pathways related to cell proliferation and glioma invasion, angiogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis.22-25 Table 2 reports the classification of the target therapies used for malignant brain tumors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of Target Therapies for Malignant Brain Tumors

| Target Therapy | ||

| Candidate Drugs | Target | Biological Role in GBM |

| TKIs | EGFRvIII | Proliferation, migration, invasion, and resistance to apoptosis |

| PDGFR | ||

| FGFR | ||

| HGFR | ||

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR Is | PI3K | Growth, metabolism, proliferation, migration |

| AKT | ||

| mTORC1 | ||

| FTIs | RAS/MAPK | Cell cycle maintenance and proliferation |

| BRAF V600E | ||

| p53Is | MDM2/MDM4 | Cell cycle progression and resistance to apoptosis |

| pRBIs | CDK4/CDK6 | |

| IDHIs | IDH1 | Metabolism, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis |

| HDACIs | Histones | Dysregulation DNA transcription, expansion of gene mutations |

| AIs | VEGF-A | Blood vessel formation, proliferation, therapeutic resistance |

| VEGFR1 | ||

| PKC | Tumor microenvironment maintenance | |

| IIs | Integrins | Cell adhesion, migration, metastasis |

| PIs | Proteasome complex | Homeostasis, growth and resistance to apoptosis |

AIs Angiogenesis Inhibitors, EGFR: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; FGFR: Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor FTIs: Farnesyl Transferase Inhibitors; HDACIs: Histone Deacetylases Inhibitors; HGFR: Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor; IDH1: Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1; IDHIs: Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors; IIs: Integrin Inhibitors; mTOR: Mammalian Target of Rapamycin; mTORC1: Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1; PDGFR: Platelet- Derived Growth Receptor; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate–3; PIs: Proteasome Inhibitors; PKC: Protein Kinase C; TKIs: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors; VEGF-A: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A; VEGFR1: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1

2.1. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Tyrosine kinase receptors consist in an extracellular ligand-binding and a transmembrane tyrosine kinase domain containing sites for autophosphorylation. Upon the binding of its ligand, the receptors undergo dimerization and phosphorylation of specific tyrosines, those become binding sites, recruit proteins and activate downstream intracellular pathways, ultimately resulting in tumor maintenance and proliferation.26-28 The most widely studied tyrosine kinase receptors are the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the platelet-derived growth receptor (PDGFR), the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) and the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR). All of them are constantly overexpressed or mutated in GBMs. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are molecules which bind the aforementioned receptors, blocking their downstream signals.

2.1.1 EGFR

The EGFR gene is amplified or overexpressed in 40% to 60% of the primary GBMs, whereas loss of exons 2 to 7 (EGFRvIII) is present in 40-50% of the cases.29-31

EGFRvIII mutation leads to a ligand-independent kinase activity and, accordingly, an EGFR-pathway overactivation, resulting in increased cell proliferation, invasiveness and resistance to chemotherapeutic agents.32, 33 Gefinitib (Iressa®) and erlotinib (Tarceva®) are approved TKIs directed against EGFRvIII. Three phase II clinical trials (#NCT00025675, #NCT00238797, #NCT00016991) highlighted the efficacy of gefinitib, pointing out a progression-free survival at 6 months (PFS-6) of 13%.34 Erlotinib lacked success as a monotherapy, but enhanced the efficacy of chemo-radiotherapy, especially if associated with temozolomide (TMZ) and carmustine at a dose of 150 or 300 mg/daily.35, 36 Similar results have been reported for lapatinib, afatinib and dacomitinib.37

In addition, two monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are under observation. Cetuximab, a chimeric murine-human IgG1 Mab that binds the extracellular EGFR domain inducing tumor apoptosis.38 As a monotherapy, it demonstrated a PFS-6 of 9.2% and an increased overall survival (OS) of 5 months. In combination with bevacizumab and irinotecan cetuximab, it showed a PFS-6 of 30% and a median OS of 7.2 months.39 ABT-414, an EGFR-directed MAb conjugated to an anti-microtubulin agent, had a PFS-6 of 28.3% in monotherapy or when combined with standard temozolomide chemoradiotherapy (#NCT02573324).40

2.1.2. PDGFR

PDGFR gene amplification is found in nearly 15% of GBMs, and the receptor’s overexpression, which leads to tumor growth and angiogenesis, is frequently associated with transition from low- to high-grade glioma.30 Imatinib is the most famous PDGFR inhibitor, used in many hematological tumors for its activity against the mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (c-KIT), and oncogene fusion protein BCR-ABL.

Many phase II clinical trials have proven that imatinib monotherapy failed to improve PFS-6 or OS in patients with GBM,41 but resulted in a good response in combination with hydroxyurea.42

Sorafenib, vandetanib, dasatinib and bosutinib are other PDGFR inhibitors. However, many clinical trials have failed to demonstrate the efficacy of dasatinib, both as monotherapy and combined with radiotherapy, TMZ and lomustine.43, 44

2.1.3. FGFR

Erdafitinib, a selective FGFR TKI, showed promising results in patients with GBM harboring oncogenic FGFR-TACC fusion.45, 46

2.1.4. HGFR/c-MET

HGFR, also known as c-Met, amplification/mutation has a role in promoting gliomagenesis and drug resistance.47, 48 Crizotinib, specifically designed against c-Met, has given some results in combination with dasatinib.49, 50 Analogous results have been reported for SGX52351, 52 (#NCT00606879, #NCT00607399). Conversely, onartuzumab and rilotumumab (AMG102) basically demonstrated no clinical benefits.53, 54 Two phase II clinical trials have been completed, one with AMG102 as monotherapy (#NCT00427440), and the other with AMG102 plus bevacizumab (#NCT01113398), both for patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas.

2.2. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors

The Cancer Genome Atlas analysis highlighted the presence of PI3K/AKT/ mTOR signaling pathway dysregulation in 50-60% of GBMs.55, 56 The activation of phosphatidylinositol 4.5-bisphosphate-3 (PI3K) regulates the activity of many kinase proteins, such as AKT. It transduces the signals to many downstream intracellular effectors, like the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). A fundamental intracellular protein is mTOR, involved in cell growth signaling and tumorigenesis. It is composed of two subunits, mTORC1-2, with different roles, and mTORC1, particularly involved in the transition of the cell cycle from G1 to S. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved three mTORC1 inhibitors: sirolimus (Rapamycin, Rapamune®), everolimus® and temsirolimus®.

Temsirolimus has been evaluated in some significant clinical trials; one of these was a phase II study involving 65 patients with recurrent GBM. It demonstrated a radiographic improvement in 36% of the patients, a PFS-6 of 7.8% and median OS of 4.4 months.57

Sirolimus has been tested in combination with surgery (#NCT00047073), gefitinib in 34 recurrent glioma patients, and erlotinib (#NCT00672243), demonstrating moderate effectiveness.58

Everolimus was studied in combination with gefitinib (#NCT00085566), bevacizumab or chemioradiotherapy. A phase II clinical trial tested the combination of everolimus, TMZ and radiotherapy versus conventional standard of care (#NCT00553150).

However, mTOR inhibitors have not demonstrated significant clinical activity, if not in combination with other treatments. This is due to their selectivity for mTORC1 and not mTORC2, ensuring only a partial blocking of the mTOR function.

In fact, two novel ATP-competitive mTORC2 inhibitors (CC214-1 and CC214-2) are under investigation, in order to overcome the resistance of mTOR inhibitors.59

Other promising strategies involve the selective PI3K inhibitor, buparlisib, which has an antitumor activity, especially when associated with bevacizumab in patients with recurrent GBM.59

Perifosine is a novel selective AKT inhibitor, currently tested in some ongoing trials. A phase II study investigated perifosine as a monotherapy for recurrent malignant gliomas60 (#NCT00590954).

2.3. Farnesyl Transferase Inhibitors

Following the activation of TK receptors, the intracellular RAS protein family undergoes post-translational modifications and triggers multiple effector pathways, including the RAF and MAP kinases (MAPK) involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and survival.

However, translocation of RAS to the cell membrane requires a post-translational alteration catalyzed by the farnesyl transferase enzyme.30, 61

Farnesylation is the limiting step in RAS activities and the specific farnesyl transferase inhibitors (FTIs) lock all its functions upstream, and consequently the intracellular RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK pathway.62

Among these, tipifarnib (Zarnestra®), exhibited in a phase II trial, had modest efficacy as a monotherapy or after radiotherapy, in patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent malignant gliomas.63, 64

Lonafarnib, an FTI, was tested in a phase I clinical trial in combination with TMZ and radiotherapy, with promising results65 (#NCT00049387).

2.3.1. BRAF V600E

RAF kinases, also triggered by the RAS system, are involved in intracellular growth pathways and stimulation.

Several studies reported the presence of BRAF V600E mutation, especially in infant gliomas.66 Vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, is under investigation in a phase I ongoing trial, for children with recurrent BRAFV600E-Mutant gliomas67 (#NCT01748149).

2.4. MDM2/MDM4/p53 inhibitors

The dysregulation of p53 signaling pathways is found in more than 80% of high-grade gliomas. The p53 is fundamental in cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis; mutation results in clonal expansion of tumor cells and genetic instability.68, 69

In 20% of the patients, the p53 inactivity is due to the MDM2 or MDM4 overexpression. MDM2/MDM4 inactivates p53 and consequently leads to loss of cancer suppression.30, 70

Therefore, an effective strategy rationale is to restore the p53 activity, by molecules targeting MDM2 or MDM4. Preclinical studies demonstrated the successful suppression of GBM growth with several MDM2 inhibitors, including RG7112,71 RG7388 and AMG232 as well as many others in progress (#NCT03107780).

2.5. CDK4/CDK6/pRB inhibitors

The altered function of retinoblastoma protein (pRB) contributes to gliomagenesis in 78% of the cases and the overexpression of CDK4/CDK6 plays a fundamental role in the modulation of this pathway, involved in cell growth.72-74

Novel agents directed to CDK4 and CDK6 demonstrated strong antitumor efficacy in RB1-wild-type GBM, such as ribociclib and palbociclib.

Ribociclib was tested in a phase I trial for recurrent glioblastoma or anaplastic glioma75 (#NCT02345824); palbociclib was employed as a monotherapy for brain metastases76 (#NCT02896335).

Zotiraclib, a multi-CDK inhibitor, has been explored in clinical trials for newly diagnosed or recurrent gliomas (#NCT02942264, #NCT03224104).

2.6. Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 inhibitors

Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1) mutation is one of the most frequent abnormalities found in high-grade gliomas, and according to the World Health Organization, is a new classification of brain tumors also having predictive value of treatment response. This mutation consists in the gain-of-function with the production of D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which interferes with cellular metabolism 77, 78. Ivosidenib, an IDH1 inhibitor, is being evaluated in a phase I ongoing trial, as a monotherapy, for advanced solid tumors including IDH-mutated gliomas (#NCT02073994).

2.7. Histone deacetylases inhibitors

Histone deacetylases (HDAC) are enzymes involved in the regulation of histones, which are proteins that organize the DNA structure and regulate gene transcription.

HDAC inhibitors have an emerging role in the treatment of GBMs, potentially promoting the apoptosis of the cancer cells.79

Vorinostat, an oral quinolone HDAC inhibitor, is being studied in phase I/II clinical trials, as a monotherapy in recurrent GBM,80 and in combination with TMZ, showing good tolerance and giving promising results81 (#NCT00731731).

Panobinostat, Romidepsin and other HDAC inhibitors are still under evaluation.

2.8. Angiogenesis inhibitors

The tumor’s microenvironment, together with pathological angiogenesis and neovascularization, play a fundamental role in the development and progression of high-grade gliomas.

Acting as managers for the angiogenesis process, as well as for a wide range of CNS vascular pathologies, they are mainly vascular growth factors of all the vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and its receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, found on the glioma’s endothelial cells.82-85

Efforts to downregulate this pathway have been pursued through the development of agents directed to VEGF/VEGFR, which not only block neoangiogenesis, but also have an effect on the vascular phenotype.

The inhibition of VEGF signaling also changes the vessels’ diameter, permeability and tortuosity, decreasing tumor hypoxia and consequently disrupting the survival mechanism in glioma cells as well as increasing chemotherapy delivery and radiosensitivity.83-85

2.8.1. VEGFR

Several studies evaluated VEGFR inhibitors for patients with newly diagnosed, as well as recurrent GBM.

Vatalanib has been tested in phase I/II studies in combination with TMZ and radiotherapy (#NCT00128700). Cediranib demonstrated no clinical benefits in a phase II clinical trial as a monotherapy (#NCT00305656), yet there was greater benefit together with lomustine in a randomized phase III study86 (#NCT00503204).

Cabozantinib is a promising agent against VEGFR and MET signaling, evaluated in two phase II studies involving newly diagnosed (#NCT00960492) and recurrent GBM (#NCT00704288). Ramucirumab and icrucumab are new MAbs under evaluation, directed to VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-1, respectively.87

2.8.2. VEGF

The most relevant of the VEGF inhibitors is bevacizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A, which in 2009 received FDA-approval for the treatment of recurrent GBM, after the high radiographic response rates (ranging from 28% to 59%) achieved in two clinical trials.88, 89

The significant antitumor potential of bevacizumab has been proven in many studies, using it as a monotherapy or in combination with lomustine (#NCT01290939) and radiochemiotherapy.90, 91

Combinations of bevacizumab with the standard of care were examined in two phase III clinical trials, AVAglio92 (#NCT00943826) and RTOG- 082593 (#NCT00884741), and although both demonstrated encouraging results in PFS survival benefit, bevacizumab remains only an alternative treatment in the recurrent setting.

Another promising agent is aflibercept, known as VEGF-trap, a recombinant product fusion protein which has been studied in phase II trials with a PFS-6 of 7.7% and median OS of 3 months.94, 95

2.8.3. Protein kinase C

Protein kinase C (PKC) is implicated in activation of the angiogenesis process, cell proliferation and constitution of the microenvironment, therefore, it is a potentially attractive therapeutic target.

Enzastaurin, a potent PKC inhibitor, demonstrated in a phase I/II trial a 25% radiographic response and a PFS-6 of 7% in GBM.96

Tamoxifen, a modulator of the estrogen receptor, has been described as a PKC inhibitor and was tested in GBM therapy with a median OS of 9.7 months.97, 98

2.9. Integrin inhibitors

The integrins are transmembrane proteins which bind multiple extracellular ligands and mediate cell adhesion and migration. They are expressed at a high level in malignant glioma cells and play a central role in the angiogenesis, development, invasion and metastasis of the tumor.99, 100 Integrin inhibitors are being investigated as a means of reducing this mechanism.

Cilengitide, which competitively inhibits integrin ligand binding,101 has been evaluated in a phase I/II study stand-alone; 102 or in a phase III trial, associated to TMZ and radiotherapy, resulting in a good improvement of PFS-6103 (#NCT00689221).

Thalidomide and lenalidomide, which interfere with the expression of integrin receptors and have an antiangiogenic effect, are being studied for GBM therapy, with results that are still unsatisfactory.104-106

2.10. Proteasome inhibitors

Proteasomes are proteins with enzymatic activities involved in the regulation of homeostasis, cell growth and apoptosis.

Bortezomib (Velcade®), the most used proteasome inhibitor in the oncological field, has also been tested for GBM therapy in combination with chemioradiotherapy107 (#NCT00006773).

The pan-proteasome inhibitor, Marizomib, is currently undergoing phase III evaluation in newly diagnosed GBMs108 (#NCT03345095).

Discussion

The present literature review highlights the current role of a series of target therapies, especially tyrosine kinase and angiogenesis inhibitors, in the treatment of malignant CNS tumors.

Several steps forward have been done in the recent years toward a deep understanding of complex pathophysiologic pathways associated with a wide spectrum of neurological and neuro-oncological pathologies of adulthood and pediatric age. 109-111 Nevertheless, the lack of success of the standard of care and the still largely dismal prognosis of patients affected by high-grade gliomas dictate the urgent need of new and more effective therapeutic approaches.

In this scenario, the improved understanding of genome mutations underlying the GBM phenotype has led to greater insight into the biology of the tumor, at the same time providing the opportunity for designing novel and personalized treatment strategies.82, 112, 113

Data from the Cancer Genome Atlas project 55 revealed the complicated genetic profile of GBMs and recognized the core signaling and transduction pathways commonly involved in the growth, proliferation, angiogenesis and spreading of the tumor.114

A further tangible aspect of these advances is the latest World Health Organization’s classification of brain tumors, which integrates data from traditional histological analysis with biomolecular connotation obtained by specific genetic analysis and characterizations.115

Accordingly, the target therapies developed on the basis of the above have detected molecular abnormalities, and have made use of pharmacological agents tailored to specific mutations, specific to tumor subtypes.

Typical genetic alterations of GBMs are the overexpression of the tyrosine kinase receptors, especially the EGFR, PDGFR, FGFR and HGFR, dysregulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MAPK pathways, as well as p53 or pRB mutations.30, 116, 117

TKIs have long been investigated in several clinical trials with disappointing results. Despite the extreme specificity of these agents, they were not efficacious as a monotherapy, thus the current approach consists in the combination of multiple molecular agents within the same targets or between separate pathways.33, 118, 119

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and farnesyltransferase inhibitors show low tolerability and safe profiles during clinical studies, but have a synergistic effect only in combination with standard of care.58, 120

Likewise, agents directed at restoring p53 and pRB activity gave encouraging results in association with chemotherapy and whole brain radiotherapy.76, 121 The newly discovered alterations in metabolic pathways, including IDH1 and HDAC enzymes, seem to be up-and-coming targets. Currently, anti-angiogenetic drugs are among the most promising. They focused on the blocking of VEGF/VEGFR,122, 123 along with components of the tumor microenvironment, such as protein kinase C, integrins and proteasome complexes.89, 124, 125

Despite the rationale of the target therapies, the vast intratumoral heterogeneity and GBM cell plasticity have caused a rapid shift toward resistant tumor phenotypes, the latter responsible for the failure of the therapy.126-128

Additionally, the route of drug administration still presents a limitation for the efficacy of these therapies. Recent progress has been made through the use of stereotactic or endoscopic techniques for the intrathecal administration of pharmacological agents directly into the tumor site, also benefiting from the minimal invasiveness of these approaches, well evident also for other neurosurgical pathologies.129-131

Last but not least, the immunological tumor microenvironment, composed of glia cells and lymphocytes, consistently modulates tumor sensitivity to treatment.132-134

Conclusion

The improved knowledge of the biology of tumors has recently made it possible to transform the molecular alterations at the base of the high malignancy of GBM, into different treatment strategies.

Good results came from tyrosine kinase inhibitors, primarily erlotinib and gefinitinb. Similarly, PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors and p53 restoring agents proved their efficacy in several clinical trials. Bevacizumab, in association with TMZ and radiotherapy, has been approved for recurrent GBMs.

An in-depth identification of driver molecular alterations may make it possible to appropriately select those patients who are candidates for a target therapy.

The greatest challenge of the near future consists in overcoming the issue of escape of GBM that is present in all of these therapies.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Giorgia Di Giusto, Engineer, for her invaluable technical support during data collection and analysis.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Jiang T, Mao Y, Ma W, et al. CGCG clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult diffuse gliomas. Cancer Lett. 2016;375(2):263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricard D, Idbaih A, Ducray F, Lahutte M, Hoang-Xuan K, Delattre JY. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61346-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61346-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Glioblastoma: from molecular pathology to targeted treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130324. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130324 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16 Suppl 4:iv1–63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou223 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043330 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardee ME, Zagzag D. Mechanisms of glioma-associated neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(4):1126–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.030 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auffinger B, Spencer D, Pytel P, Ahmed AU, Lesniak MS. The role of glioma stem cells in chemotherapy resistance and glioblastoma multiforme recurrence. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(7):741–752. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1051968. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2015.1051968 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos A, Ding Z, Loftus JC, Tran NL. Molecular and Microenvironmental Determinants of Glioma Stem-Like Cell Survival and Invasion. Front Oncol. 2017;7:120. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00120 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prelaj A, Rebuzzi SE, Grassi M, et al. Multimodal treatment for local recurrent malignant gliomas: Resurgery and/or reirradiation followed by chemotherapy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;10(1):49–57. doi: 10.3892/mco.2018.1745. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2018.1745 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual-Castroviejo I, Lopez-Pereira P, Savasta S, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Lago CM, Cisternino M. Neurofibromatosis type 1 with external genitalia involvement presentation of 4 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(11):1998–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.01.074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.01.074 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savasta S, Chiapedi S, Perrini S, Tognato E, Corsano L, Chiara A. Pai syndrome: a further report of a case with bifid nose, lipoma, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24(6):773–776. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0613-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-008-0613-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salpietro V, Mankad K, Kinali M, et al. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension and the underlying endocrine-metabolic dysfunction: a pilot study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27(1-2):107–115. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0156. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2013-0156 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosadini M, Granata T, Matricardi S, et al. Relapse risk factors in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(9):1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14267. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14267 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng CY, Shetty R, Sekhar LN. Microsurgical Resection of a Large Intraventricular Trigonal Tumor: 3-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;15(6):E92–E93. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy068. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy068 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palumbo P, Lombardi F, Siragusa G, et al. Involvement of NOS2 Activity on Human Glioma Cell Growth, Clonogenic Potential, and Neurosphere Generation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms19092801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19092801 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luzzi S, Crovace AM, Del Maestro M, et al. The cell-based approach in neurosurgery: ongoing trends and future perspectives. Heliyon. 2019;5(11):e02818. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02818 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luzzi S, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, et al. Anterolateral Approach for Retrostyloid Superior Parapharyngeal Space Schwannomas Involving the Jugular Foramen Area: A 20-Year Experience. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e40–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spena G, Roca E, Guerrini F, et al. Risk factors for intraoperative stimulation-related seizures during awake surgery: an analysis of 109 consecutive patients. J Neurooncol. 2019;145(2):295–300. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03295-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03295-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonosante A, Brandolini L, d’Angelo M, et al. Autocrine CXCL8-dependent invasiveness triggers modulation of actin cytoskeletal network and cell dynamics. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(2):1928–1951. doi: 10.18632/aging.102733. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102733 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson JRD, Regad T. Targeting cellular pathways in glioblastoma multiforme. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17040. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.40 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164382 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(3):157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, et al. Molecular Profiling Reveals Biologically Discrete Subsets and Pathways of Progression in Diffuse Glioma. Cell. 2016;164(3):550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szopa W, Burley TA, Kramer-Marek G, Kaspera W. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Biomarkers in Glioblastoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8013575. doi: 10.1155/2017/8013575. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8013575 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakada M, Kita D, Teng L, et al. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases: Principles and Functions in Glioma Invasion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1202:151–178. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30651-9_8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30651-9_8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrasco-Garcia E, Saceda M, Martinez-Lacaci I. Role of receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligands in glioblastoma. Cells. 2014;3(2):199–235. doi: 10.3390/cells3020199. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells3020199 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang K, Huang R, Wu C, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase expression in high-grade gliomas before and after chemoradiotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(6):6509–6515. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.11017. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.11017 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelloski CE, Ballman KV, Furth AF, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III status defines clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2288–2294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0705. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0705 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan HK, Kaye AH, Luwor RB. The EGFRvIII variant in glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(6):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An Z, Aksoy O, Zheng T, Fan QW, Weiss WA. Epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma: signaling pathways and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2018;37(12):1561–1575. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0045-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-017-0045-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felsberg J, Hentschel B, Kaulich K, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Variant III (EGFRvIII) Positivity in EGFR-Amplified Glioblastomas: Prognostic Role and Comparison between Primary and Recurrent Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(22):6846–6855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0890. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0890 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich JN, Reardon DA, Peery T, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):133–142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raizer JJ, Abrey LE, Lassman AB, et al. A phase II trial of erlotinib in patients with recurrent malignant gliomas and nonprogressive glioblastoma multiforme postradiation therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(1):95–103. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop015. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nop015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Rampling R, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib versus temozolomide or carmustine in recurrent glioblastoma: EORTC brain tumor group study 26034. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1268–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5984. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5984 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reardon DA, Nabors LB, Mason WP, et al. Phase I/randomized phase II study of afatinib, an irreversible ErbB family blocker, with or without protracted temozolomide in adults with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(3):430–439. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou160. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou160 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukai J, Nishio K, Itakura T, Koizumi F. Antitumor activity of cetuximab against malignant glioma cells overexpressing EGFR deletion mutant variant III. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(10):2062–2069. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00945.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00945.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hasselbalch B, Eriksen JG, Broholm H, et al. Prospective evaluation of angiogenic, hypoxic and EGFR-related biomarkers in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme treated with cetuximab, bevacizumab and irinotecan. APMIS. 2010;118(8):585–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02631.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02631.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips AC, Boghaert ER, Vaidya KS, et al. ABT-414, an Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting a Tumor-Selective EGFR Epitope. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(4):661–669. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0901. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0901 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen PY, Yung WK, Lamborn KR, et al. Phase I/II study of imatinib mesylate for recurrent malignant gliomas: North American Brain Tumor Consortium Study 99–08. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(16):4899–4907. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0773. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0773 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reardon DA, Egorin MJ, Quinn JA, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate plus hydroxyurea in adults with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9359–9368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2185. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2185 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lassman AB, Pugh SL, Gilbert MR, et al. Phase 2 trial of dasatinib in target-selected patients with recurrent glioblastoma (RTOG 0627) Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(7):992–998. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov011. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov011 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galanis E, Anderson SK, Twohy EL, et al. A phase 1 and randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of bevacizumab plus dasatinib in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: Alliance/North Central Cancer Treatment Group N0872. Cancer. 2019;125(21):3790–3800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32340. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Stefano AL, Fucci A, Frattini V, et al. Detection, Characterization, and Inhibition of FGFR-TACC Fusions in IDH Wild-type Glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(14):3307–3317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2199. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2199 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh D, Chan JM, Zoppoli P, et al. Transforming fusions of FGFR and TACC genes in human glioblastoma. Science. 2012;337(6099):1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1220834. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1220834 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sierra JR, Tsao MS. c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3(1 Suppl):S21–35. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834011422557 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie Q, Bradley R, Kang L, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) autocrine activation predicts sensitivity to MET inhibition in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(2):570–575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119059109. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1119059109 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Broniscer A, Jia S, Mandrell B, et al. Phase 1 trial, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of dasatinib combined with crizotinib in children with recurrent or progressive high-grade and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(7):e27035. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27035. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27035 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chi AS, Batchelor TT, Kwak EL, et al. Rapid radiographic and clinical improvement after treatment of a MET-amplified recurrent glioblastoma with a mesenchymal-epithelial transition inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(3):e30–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4586. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4586 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchanan SG, Hendle J, Lee PS, et al. SGX523 is an exquisitely selective, ATP-competitive inhibitor of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase with antitumor activity in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(12):3181–3190. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0477. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0477 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guessous F, Zhang Y, diPierro C, et al. An orally bioavailable c-Met kinase inhibitor potently inhibits brain tumor malignancy and growth. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10(1):28–35. doi: 10.2174/1871520611009010028. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871520611009010028 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martens T, Schmidt NO, Eckerich C, et al. A novel one-armed anti-c-Met antibody inhibits glioblastoma growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):6144–6152. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1418. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1418 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchanan IM, Scott T, Tandle AT, et al. Radiosensitization of glioma cells by modulation of Met signalling with the hepatocyte growth factor neutralizing antibody, AMG102. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(9):1999–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01122.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01122.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07385 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polivka J, Jr, Janku F. Molecular targets for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142(2):164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wick W, Gorlia T, Bady P, et al. Phase II Study of Radiotherapy and Temsirolimus versus Radiochemotherapy with Temozolomide in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma without MGMT Promoter Hypermethylation (EORTC 26082) Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(19):4797–4806. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3153. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3153 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, et al. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23(4):357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gini B, Zanca C, Guo D, et al. The mTOR kinase inhibitors, CC214-1 and CC214-2, preferentially block the growth of EGFRvIII-activated glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(20):5722–5732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0527. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0527 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Momota H, Nerio E, Holland EC. Perifosine inhibits multiple signaling pathways in glial progenitors and cooperates with temozolomide to arrest cell proliferation in gliomas in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7429–7435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1042. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1042 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pandey V, Bhaskara VK, Babu PP. Implications of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in glioma. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(2):114–127. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23687. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23687 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sebti SM, Adjei AA. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Semin Oncol. 2004;31(1 Suppl 1):28–39. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.012. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cloughesy TF, Wen PY, Robins HI, et al. Phase II trial of tipifarnib in patients with recurrent malignant glioma either receiving or not receiving enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(22):3651–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2323. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2323 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lustig R, Mikkelsen T, Lesser G, et al. Phase II preradiation R115777 (tipifarnib) in newly diagnosed GBM with residual enhancing disease. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(6):1004–1009. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-070. https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2008-070 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chaponis D, Barnes JW, Dellagatta JL, et al. Lonafarnib (SCH66336) improves the activity of temozolomide and radiation for orthotopic malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2011;104(1):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0502-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-010-0502-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kleinschmidt-De Masters BK, Aisner DL, Birks DK, Foreman NK. Epithelioid GBMs show a high percentage of BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(5):685–698. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827f9c5e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827f9c5e . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):726–736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1502309 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vousden KH, Lane DP. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(4):275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2147 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duffy MJ, Synnott NC, McGowan PM, Crown J, O’Connor D, Gallagher WM. p53 as a target for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(10):1153–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.10.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.10.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reifenberger G, Liu L, Ichimura K, Schmidt EE, Collins VP. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM2 gene in a subset of human malignant gliomas without p53 mutations. Cancer Res. 1993;53(12):2736–2739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verreault M, Schmitt C, Goldwirt L, et al. Preclinical Efficacy of the MDM2 Inhibitor RG7112 in MDM2-Amplified and TP53 Wild-type Glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(5):1185–1196. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1015. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic alterations and signaling pathways in the evolution of gliomas. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(12):2235–2241. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01308.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01308.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wiedemeyer WR, Dunn IF, Quayle SN, et al. Pattern of retinoblastoma pathway inactivation dictates response to CDK4/6 inhibition in GBM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(25):11501–11506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001613107. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001613107 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barton KL, Misuraca K, Cordero F, et al. PD-0332991, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, significantly prolongs survival in a genetically engineered mouse model of brainstem glioma. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077639 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tien AC, Li J, Bao X, et al. A Phase 0 Trial of Ribociclib in Recurrent Glioblastoma Patients Incorporating a Tumor Pharmacodynamic-and Pharmacokinetic-Guided Expansion Cohort. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5777–5786. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0133. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0133 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taylor JW, Parikh M, Phillips JJ, et al. Phase-2 trial of palbociclib in adult patients with recurrent RB1-positive glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2018;140(2):477–483. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2977-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2977-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xia L, Wu B, Fu Z, et al. Prognostic role of IDH mutations in gliomas: a meta-analysis of 55 observational studies. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17354–17365. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4008. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4008 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Polivka J, Polivka J, Jr, Rohan V, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 mutations as prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma multiforme patients in West Bohemia. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:735659. doi: 10.1155/2014/735659. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/735659 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alvarez AA, Field M, Bushnev S, Longo MS, Sugaya K. The effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on glioblastoma-derived stem cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;55(1):7–20. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0329-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-014-0329-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Galanis E, Jaeckle KA, Maurer MJ, et al. Phase II trial of vorinostat in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a north central cancer treatment group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):2052–2058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.0694. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.0694 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee EQ, Puduvalli VK, Reid JM, et al. Phase I study of vorinostat in combination with temozolomide in patients with high-grade gliomas: North American Brain Tumor Consortium Study 04-03. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(21):6032–6039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1841. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1841 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamran N, Calinescu A, Candolfi M, et al. Recent advances and future of immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16(10):1245–1264. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2016.1212012. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2016.1212012 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):7843–7848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Popescu AM, Purcaru SO, Alexandru O, Dricu A. New perspectives in glioblastoma antiangiogenic therapy. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2016;20(2):109–118. doi: 10.5114/wo.2015.56122. https://doi.org/10.5114/wo.2015.56122 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jain RK, di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Loeffler JS, Sorensen AG, Batchelor TT. Angiogenesis in brain tumours. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(8):610–622. doi: 10.1038/nrn2175. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2175 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Batchelor TT, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, et al. Phase II study of cediranib, an oral pan-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2817–2823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3988. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3988 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hsu JY, Wakelee HA. Monoclonal antibodies targeting vascular endothelial growth factor: current status and future challenges in cancer therapy. BioDrugs. 2009;23(5):289–304. doi: 10.2165/11317600-000000000-00000. https://doi.org/10.2165/11317600-000000000-00000 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):740–745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taal W, Oosterkamp HM, Walenkamp AM, et al. Single-agent bevacizumab or lomustine versus a combination of bevacizumab plus lomustine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (BELOB trial): a randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):943–953. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70314-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70314-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and Bevacizumab in Progressive Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954–1963. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707358 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chinot OL, de La Motte Rouge T, Moore N, et al. AVAglio: Phase 3 trial of bevacizumab plus temozolomide and radiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Adv Ther. 2011;28(4):334–340. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0007-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-011-0007-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1308573 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Groot JF, Lamborn KR, Chang SM, et al. Phase II study of aflibercept in recurrent malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2689–2695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1636. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1636 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gomez-Manzano C, Holash J, Fueyo J, et al. VEGF Trap induces antiglioma effect at different stages of disease. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(6):940–945. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-061. https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2008-061 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kreisl TN, Kotliarova S, Butman JA. A phase I/II trial of enzastaurin in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(2):181–189. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop042. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nop042 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Baltuch GH, Couldwell WT, Villemure JG, Yong VW. Protein kinase C inhibitors suppress cell growth in established and low-passage glioma cell lines. A comparison between staurosporine and tamoxifen. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(3):495–501. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199309000-00021. discussion 501. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-199309000-00021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robins HI, Won M, Seiferheld WF, et al. Phase 2 trial of radiation plus high-dose tamoxifen for glioblastoma multiforme: RTOG protocol BR-0021. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8(1):47–52. doi: 10.1215/S1522851705000311. https://doi.org/10.1215/S1522851705000311 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tabatabai G, Tonn JC, Stupp R, Weller M. The role of integrins in glioma biology and anti-glioma therapies. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(23):2402–2410. doi: 10.2174/138161211797249189. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161211797249189 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Corsini NS, Martin-Villalba A. Integrin alpha 6: anchors away for glioma stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(5):403–404. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reardon DA, Nabors LB, Stupp R, Mikkelsen T. Cilengitide: an integrin-targeting arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide with promising activity for glioblastoma multiforme. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(8):1225–1235. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.8.1225. https://doi.org/10.1517/13543784.17.8.1225 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gilbert MR, Kuhn J, Lamborn KR, et al. Cilengitide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the results of NABTC 03-02, a phase II trial with measures of treatment delivery. J Neurooncol. 2012;106(1):147–153. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0650-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0650-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nabors LB, Fink KL, Mikkelsen T, et al. Two cilengitide regimens in combination with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma and unmethylated MGMT gene promoter: results of the open-label, controlled, randomized phase II CORE study. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(5):708–717. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou356. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou356 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fadul CE, Kingman LS, Meyer LP, et al. A phase II study of thalidomide and irinotecan for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2008;90(2):229–235. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9655-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-008-9655-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alexander BM, Wang M, Yung WK, et al. A phase II study of conventional radiation therapy and thalidomide for supratentorial, newly-diagnosed glioblastoma (RTOG 9806) J Neurooncol. 2013;111(1):33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0987-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-012-0987-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fine HA, Kim L, Albert PS, et al. A phase I trial of lenalidomide in patients with recurrent primary central nervous system tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):7101–7106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1546. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1546 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vlachostergios PJ, Hatzidaki E, Befani CD, Liakos P, Papandreou CN. Bortezomib overcomes MGMT-related resistance of glioblastoma cell lines to temozolomide in a schedule-dependent manner. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31(5):1169–1181. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9968-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-013-9968-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Potts BC, Albitar MX, Anderson KC, et al. Marizomib, a proteasome inhibitor for all seasons: preclinical profile and a framework for clinical trials. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11(3):254–284. doi: 10.2174/156800911794519716. https://doi.org/10.2174/156800911794519716 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Parisi P, Vanacore N, Belcastro V, et al. Clinical guidelines in pediatric headache: evaluation of quality using the AGREE II instrument. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:57. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-57 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Foiadelli T, Piccorossi A, Sacchi L, et al. Clinical characteristics of headache in Italian adolescents aged 11-16 years: a cross-sectional questionnaire school-based study. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0486-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0486-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garone G, Reale A, Vanacore N, et al. Acute ataxia in paediatric emergency departments: a multicentre Italian study. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(8):768–774. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315487. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315487 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Polivka J, Jr, Polivka J, Rohan V, Topolcan O, Ferda J. New molecularly targeted therapies for glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(7):2935–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen R, Cohen AL, Colman H. Targeted Therapeutics in Patients With High-Grade Gliomas: Past, Present, and Future. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17(8):42. doi: 10.1007/s11864-016-0418-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-016-0418-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555(7697):469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature26000. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature26000 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Le Rhun E, Preusser M, Roth P, et al. Molecular targeted therapy of glioblastoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;80:101896. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101896 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lassman AB, Rossi MR, Raizer JJ, et al. Molecular study of malignant gliomas treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: tissue analysis from North American Brain Tumor Consortium Trials 01-03 and 00-01. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(21):7841–7850. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0421. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0421 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.van den Bent MJ, Gao Y, Kerkhof M, et al. Changes in the EGFR amplification and EGFRvIII expression between paired primary and recurrent glioblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(7):935–941. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov013. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov013 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ma DJ, Galanis E, Anderson SK, et al. A phase II trial of everolimus, temozolomide, and radiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: NCCTG N057K. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(9):1261–1269. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou328. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou328 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wick W, Dettmer S, Berberich A, et al. N2M2 (NOA-20) phase I/II trial of molecularly matched targeted therapies plus radiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed non-MGMT hypermethylated glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(1):95–105. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy161. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noy161 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Anthony C, Mladkova-Suchy N, Adamson DC. The evolving role of antiangiogenic therapies in glioblastoma multiforme: current clinical significance and future potential. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(9):787–797. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1650019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2019.1650019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mastrella G, Hou M, Li M, et al. Targeting APLN/APLNR Improves Antiangiogenic Efficiency and Blunts Proinvasive Side Effects of VEGFA/VEGFR2 Blockade in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79(9):2298–2313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0881. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0881 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Roth P, Silginer M, Goodman SL, et al. Integrin control of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway in glioblastoma. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 2):564–576. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws351. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws351 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kong XT, Nguyen NT, Choi YJ, et al. Phase 2 Study of Bortezomib Combined With Temozolomide and Regional Radiation Therapy for Upfront Treatment of Patients With Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme: Safety and Efficacy Assessment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(5):1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.001 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E, et al. Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(19):1350–1354. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431901. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200011093431901 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Osuka S, Van Meir EG. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma: the way forward. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(2):415–426. doi: 10.1172/JCI89587. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI89587 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Noch EK, Ramakrishna R, Magge R. Challenges in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: Multisystem Mechanisms of Therapeutic Resistance. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Luzzi S, Zoia C, Rampini AD, et al. Lateral Transorbital Neuroendoscopic Approach for Intraconal Meningioma of the Orbital Apex: Technical Nuances and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.152 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Arnaout MM, Luzzi S, Galzio R, Aziz K. Supraorbital keyhole approach: Pure endoscopic and endoscope-assisted perspective. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;189:105623. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Millimaggi DF, Norcia VD, Luzzi S, Alfiero T, Galzio RJ, Ricci A. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion with Percutaneous Bilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation for Lumbosacral Spine Degenerative Diseases. A Retrospective Database of 40 Consecutive Cases and Literature Review. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28(3):454–461. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Da Ros M, De Gregorio V, Iorio AL, et al. Glioblastoma Chemoresistance: The Double Play by Microenvironment and Blood-Brain Barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10) doi: 10.3390/ijms19102879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19102879 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jia D, Li S, Li D, Xue H, Yang D, Liu Y. Mining TCGA database for genes of prognostic value in glioblastoma microenvironment. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10(4):592–605. doi: 10.18632/aging.101415. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101415 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]