Abstract

One week after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak a global health emergency we conducted a survey to explore knowledge and attitudes on 2019-nCoV, recently renamed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in a large cohort of hospital staff. A representative sample of 2,046 hospital staff of a large university hospital in northern Italy (54% healthcare workers and 46% administrative staff, overall response rate: 25%) was administered an online questionnaire: overall there is good knowledge on 2019-nCoV control measures. The mean of correct answers for questions on general aspects of 2019-nCoV epidemic was 71.6% for HCWs and 61.2% for non-HCWs. The mean of correct answers for questions on 2019-nCoV patient management was 57.8% among HCWs. Nevertheless, on recommended precautions, also among healthcare workers there is still much to do in order to promote effective control measures and correct preventive behaviours at the individual level.

Keywords: 2019-novel coronavirus, COVID-19, healthcare workers, knowledge and attitudes, infection control and prevention measures, emergency preparedness

Background

The very first news about the emergence of a novel coronavirus, firstly named 2019-nCoV and then renamed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (1), in Hubei province, China, dated back to mid-December 2019. Only during January 2020 global awareness of this potential challenge for public health raised. On January 30th, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (2).

Even the most developed economies and healthcare systems in the world could be in significant difficulty facing the same epidemic ongoing in China (3).

The WHO, Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) were quite soon involved in the surveillance of the 2019-nCoV spreading through careful epidemiological reports and worldwide situation updates (4). Nevertheless, to deal with this threat, national and international authorities started producing several recommendations on the most different aspects of this emergency, included risk assessment guidelines (5), travel advice (6), technical guidance (7), case definition and frequently asked questions (FAQs) (8,9).

In Italy, the Ministry of Health produced circular letters on case definition, patient management and travel restrictions (10,11). According to the Italian National Health System, these documents were adopted and published by the Regions, too.

However, as long as the situation evolved, extraordinary measures of public health were adopted by Chinese authorities with an unprecedented quarantine of wholes cities and provinces and millions of citizens involved. For instance, also the Italian government forbade direct flights from and to China (11). This administrative order was very contested but avoiding travelling in China is today the easiest way to prevent cases in other countries (6).

All these interventions, along with the extensive use of the internet and social networks, led to the massive engagement of public opinion. The participation of media to the distribution of information and updates on the evolving epidemiology and restrictions, but also on the virology, clinics and available treatments, was crucial. General population conscious involvement is quite a new element in the management of this type of events. Recently, WHO was forced to take steps in order to ensure that the coronavirus epidemic did not spark a dangerous social media “infodemic” fueled by false information (12).

In this context, healthcare workers (HCWs) and in general hospital and public services staff, even if not directly involved implementing control measures, are key target populations of health authorities recommendations on 2019-nCoV control (13,14), with particular reference to suspected case hospital management and infection control (IC) precautions in hospital and community settings.

Fully aware and well-trained HCWs and workers in public services are a unique resource to keep health systems active and tackle the potential epidemic (15,16). Most studies show that in everyday assistance HCWs do not often observe standard precautions such as hand washing or rubbing (17,18), that are the first-line measures to prevent the new epidemic, too.

As of today, no studies had yet assessed the general knowledge on this new pathogen and the awareness on case management and IC measures recommended during hospital care and everyday life.

Objective

Aim of the current study was to assess concern, general and specific knowledge (modes of transmission, clinical presentations, and IC precautions) and health-related knowledge (case management and treatment) among hospital staff of a large Italian teaching hospital on novel coronavirus 2019 in the very first phase of the world epidemic.

Specific objectives were to investigate differences in the knowledge of 2019-nCoV between HCWs and other workers.

Methods

San Raffaele Hospital (OSR) is a 2-site tertiary-care referral hospital in Milan, Lombardy, with more than 1,300-beds hosting a private University (Vita-Salute San Raffaele University) with a medical, nursing, public health and dental school, among others.

The Infection Control Unit, in collaboration with the School of Public Health, developed a 7-item ques- tionnaire on the 2019-nCoV, its transmission and prevention, as well as on perceived attitudes on the on- going epidemic (available as supplementary material in Appendix 1).

Along the lines of a previous Italian study on Zika virus (19), questions were developed ad hoc, starting from brainstorming ideas and selected publications from the leading international sources. Developers had been working on the matter from the very beginning of the emergency and were daily updated on the topic.

Five questions addressed all staff while two additional questions only addressed HCWs. In order to stratify responders by professional category (HCWs or not), we introduced Question 6, and we collected only surveys where the responder answered to it.

The survey was set up using SurveyMonkey® and online administered to all OSR staff through company email. The data collection lasted seventy-two hours between February 4th and 7th 2020.

Answers were collected on a voluntary basis and responses were anonymous. Hence, it was not considered necessary to seek ethical approval.

We report descriptive analysis of 2019-nCov knowledge and attitudes distribution in HCWs and other staff. Data were statistically analysed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results and Discussion

A total of 2,046 OSR staff answered the questionnaire (response rate 25%), including HCPs (physician, nurses, midwives, healthcare assistant, physiotherapists, respiratory technicians, X-ray technicians), administrative and technical staff, laboratory and research staff and they included employees, as well as medical residents and consultants.

We excluded 19 surveys on the basis of unanswered Question 6: therefore, 2,027 responses were analyzed.

Among the total number of 2,027 responders included, 1,102 declared themselves as HCWs or HCWs in training (54%), and 924 identified themselves as non-HCWs (46%).

Numbers and percentages of responses in each group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey (questions and possible answers) and relative results presented as total and divided for healthcare workers, also in training, and non-healthcare workers (numbers and percentages). Correct answers presented in bold.

| Questions | Possible answers | HCW response (%) | not-HCW response (%) | Total (%) | |

| 1 | Are you worried about novel coronavirus? | A lot | 73 (6.6) | 85 (9.2) | 158 (7.8) |

| Quite enough | 595 (54) | 457 (49.6) | 1052 (52) | ||

| Little | 379 (34.4) | 338 (36.7) | 717 (35.4) | ||

| Not at all | 54 (4.9) | 42 (4.6) | 96 (4.7) | ||

| 2 | What is the main mode of interhuman transmission of novel coronavirus? | Airborne | 278 (25.3) | 309 (33.5) | 587 (29) |

| Droplet spread | 785 (71.4) | 562 (61) | 1347 (66.6) | ||

| Direct contact | 37 (3.4) | 49 (5.3) | 86 (4.3) | ||

| It is not transmitted. | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| 3 | Which clinical forms are caused by novel coronavirus? | Asymptomatic form | 6 (0.5) | 8 (0.9) | 14 (0.7) |

| Flu-like form | 221 (20.1) | 285 (30.9) | 506 (25) | ||

| Severe pneumonia | 74 (6.7) | 125 (13.5) | 199 (9.8) | ||

| All the previous | 799 (72.6) | 505 (54.7) | 1304 (64.5) | ||

| 4 | Nowadays, in Italy, how can you protect yourself from novel coronavirus? | Avoiding crowded places | 455 (41.4) | 378 (41.2) | 833 (41.3) |

| Not travelling in China | 575 (52.3) | 461 (50.3) | 1036 (51.4) | ||

| Wearing always a surgical mask | 67 (6.1) | 69 (7.5) | 136 (6.7) | ||

| Not going to Chinese restaurant | 2 (0.2) | 9 (1) | 11 (0.5) | ||

| 5 | What should I do in common areas, if I have a cold or flu? | Coughing and sneezing covering nose and mouth (with a napkin or upper arm) | 68 (6.7) | 123 (14.2) | 191 (10.1) |

| Often washing hands | 27 (2.7) | 47 (5.4) | 74 (3.9) | ||

| Keeping distance from other people, if possible | 4 (0.4) | 15 (1.7) | 19 (1) | ||

| All the previous | 916 (90.2) | 683 (78.7) | 1599 (84.9) | ||

| 6 | Are you a healthcare worker, also in training? | Yes | 1102 (100) | 0 | 1102 (54.4) |

| No | 0 (0) | 924 (100) | 924 (45.6) | ||

| 7 | Which precautions are recommended by the Ministry of Health? | Standard precautions | 251 (24.1) | ||

| Airborne precautions | 337 (32.3 | ||||

| Contact precautions | 26 (2.5) | ||||

| Eye protection | 1 (0.1) | ||||

| All the previous | 427 (41) | ||||

| 8 | Which measure are available today against novel coronavirus? | Vaccine | 6 (0.6) | ||

| Specific therapy | 29 (2.8) | ||||

| Supportive therapy | 780 (74.5) | ||||

| All the previous | 6 (0.6) | ||||

| None of the previous | 226 (21.6) | ||||

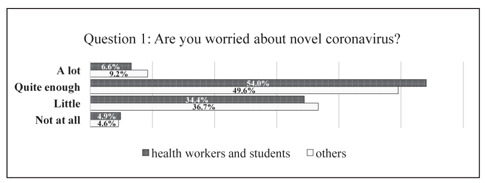

In terms of concern for the incoming pathogen, almost 60% of the responders showed quite enough or a lot worry about 2019-nCoV, as shown in Figure 1. There was little difference across the two groups: non-HCWs are slightly more concerned than the HCWs, probably because they are less well aware of the topic (16).

Figure 1.

Answers for Question 1, presented as percentages and divided between healthcare workers, also in training, and non-healthcare workers

On the question relating to modes of transmission of 2019-nCoV, the latest pieces of evidence declared that droplets are involved in the virus spread (20,21), and most of the responders answered correctly. An important proportion (33.5%) of non-HCWs answered that 2019-nCoV has an airborne transmission: this can be explained with the non-medical preparation that did not allowed distinguish the subtle but relevant difference between airborne and droplets transmission. There was also significant variation in correct reply to the question between HCWs and non-HCWs: among the second ones 61% supposed a droplets transmission against the 71.4% of HCWs.

When asked about the clinical presentations of the new infection (22–24), there were essential elements of variation between the two groups: 72.6% of HCWs answered correctly to the question stressing the wide range of possible presentations of the epidemic. At the same time, non-HCWs focused on the flu-like form, that is one of the most common forms of frequent respiratory infections. Moreover, adding up those who answered “Flu-like form” and “Severe pneumonia”, a proportion of 34.8% responders excluded asymptomatic form of the infection (25), which could be quite a big problem in the containment of the epidemic.

On the question about personal protection from 2019-nCoV in everyday life in Italy (Question 4), most (more than 50%) of the responders in both groups answered adequately. It must be reported that in both groups the same quite high percentage of more than 41% suggested avoiding crowded places, that is nowadays a useless prevention measure in Italy (9). As a matter of fact, on the 7th February 2020, in Italy, 2019-nCoV transmission had not yet been confirmed, and there were only three confirmed cases of infection in travellers from China (26).

On the question about cough etiquette in common areas (Question 5), a very high percentage answered accurately in both groups, even if amongst HCWs there was a higher level of awareness of all the actions suggested (9,27).

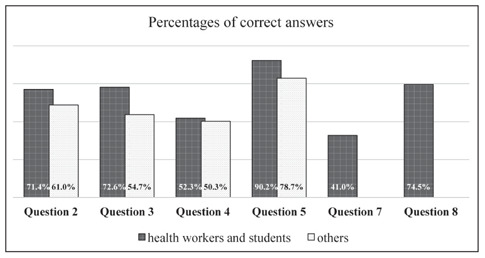

On these first five questions of the survey, there were uniform trends in the answers in the two groups. Generally, HCWs were more aware and answered correctly with higher percentages (mean of correct answers 71.6%) than non-HCWs (mean of correct answers 61.2%), as shown in Figure 2. Only in Question 4, there were tiny differences in the answers, maybe because of the relevant and frequent campaign on public media against fake news that reaches the public opinion with compelling messages (28).

Figure 2.

Percentages of correct answers for Questions 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8, divided between healthcare workers, also in training, and non-healthcare workers.

Only auto-declared HCWs answered to the last two questions.

On the question regarding IC precautions recommended by the Italian Ministry of Health (Question 7), only 41% answered properly. Most of the responders missed the recommendations to adopt simultaneously standard, contact and airborne precautions plus eye protection in the management of suspected and confirmed cases, as proposed by national and international authorities (29,30). Regarding the droplets transmission of 2019-nCoV (20), the surgical mask could be the appropriate protection needed, but Italian health authorities preferred to raise the level of prevention measures.

On the last question of the survey, on available treatments, a very high percentage of HCWs answered correctly (74.5%), that is that only supportive therapy is now available and vaccine or specific drugs are not at disposal today (30).

The last two questions showed that among HCWs there is a generally good knowledge on the topic and the specific measures of IC recommended by health authorities and by the Chief-medical Office of OSR.

We acknowledge our study bears several limitations, including the fact that the survey was relatively short, online administered and not previously validated. Moreover, the study design was cross-sectional, and answers were exclusively self-reported and suffered from social desirability bias and voluntary enrolment.

Among conceptual limitations, there was the imprecise classification of the subjects: Question 6 allowed to distinguish only between HCWs, also in training, and non-HCWs. Another one was the lack of a specific answer on the case definition of COVID-19. It would have been quite interesting testing awareness of this topic since this is the first issue in the Emergency Department that nurses and physicians are facing. The rigorous knowledge of clinical and epidemiological criteria should lead the case management.

However, we are among the first to explore hospital staff knowledge and attitudes on 2019-nCoV, reporting data from a large study population. In the context of the ongoing public health emergency, it is of utmost importance that hospital staff and HCWs are adequately trained and informed so as to behave at their best to control infection transmission (31,32). Our data can inform the planning, implementation and evaluation of ad hoc targeted preventive interventions, as well as stimulate similar research in other settings and over time.

Aknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Gorbalenya AE. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus – The species and its viruses, a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv. 2020 Feb 11; 2020.02.07.937862 [Google Scholar]

- 2.[Internet]. Ensuring an Infectious Disease Workforce: Education and Training Needs for the 21st Century: Workshop Summary 2006. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21850783 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiura Jung, Linton Kinoshita, Yang Hayashi, et al. The Extent of Transmission of Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, 2020. J Clin Med. 2020 Jan 24;9(2):330. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Situation reports [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7] Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. / [Google Scholar]

- 5.Current risk assessment on the novel coronavirus situation, 13 February 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14] Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/current-risk-assessment-novel-coronavirus-situation . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travel advice [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7] Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/travel-advice . [Google Scholar]

- 7. Technical guidance [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance . [Google Scholar]

- 8. Q&A on coronaviruses [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses . [Google Scholar]

- 9. FAQ - Infezione da coronavirus 2019-nCoV [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioFaqNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=228 . [Google Scholar]

- 10. Circolari e ordinanze [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/archivioNormativaNuovoCoronavirus.jsp . [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trova Norme & Concorsi - Normativa Sanitaria [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto?id=72991&completo=true . [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200202-sitrep-13-ncov-v3.pdf?sfvrsn=195f4010_6 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ippolito G, Puro V, Heptonstall J. Hospital preparedness to bioterrorism and other infectious disease emergencies. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2006;63:2213–22. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6309-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ensuring an Infectious Disease Workforce. National Academies Press; 2006. Ensuring an Infectious Disease Workforce. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agaba GO, Kyrychko YN, Blyuss KB. Mathematical model for the impact of awareness on the dynamics of infectious diseases. Math Biosci. 2017 Apr 1;286:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rai RK, Misra AK, Takeuchi Y. Modeling the impact of sanitation and awareness on the spread of infectious dis-eases. Math Biosci Eng. 2019;16(2):667–700. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2019032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parmeggiani C, Abbate R, Marinelli P, et al. Healthcare workers and health care-associated infections: Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in emergency departments in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010 Feb 23;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olalekan Adebimpe W, Adebimpe WO, Olalekan Adebim-pe W. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Use of Safety Precautions Among Health Care Workers in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital, 1 Year After the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic. Ann Glob Heal. 2017 Mar 8;82(5):897. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gianfredi V, Bragazzi NL, Nucci D, et al. Design and vali-dation of a self-administered questionnaire to assess knowl-edge, attitudes and behaviours about Zika virus infection among general population in Italy. A pilot study conducted among Italian residents in public health. Epidemiol Biostat Public Heal. 2017;14(4):e12662–1-e12662-8. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Transmission of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission . html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Cor-onavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 29 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;6736(20):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuk-Woo Chan J, Yuan S, Kok K-H, et al. A familial clus-ter of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavi-rus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Symptoms of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) | CDC [In-ternet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/symptoms.html . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 30 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Covid-19 - Situazione in Italia e nel mondo [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5338&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto . [Google Scholar]

- 27. Advice for public [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . [Google Scholar]

- 28. Risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) readiness and response to the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/risk-communication-and-community-engagement-readiness-and-initial-response-for-novel-coronaviruses-(-ncov) [Google Scholar]

- 29. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125 . [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patient management [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/patient-management . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gianfredi V, Grisci C, Nucci D, et al. Recenti Progressi in Medicina. Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore s.r.l. Communication in health. 2018;109:374–83. doi: 10.1701/2955.29706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gianfredi V, Nucci D, Salvatori T, Orlacchio F, Villarini M, Moretti M, et al. “PErCEIVE in Umbria”: evaluation of anti-influenza vaccination’s perception among Umbrian pharmacists. J Prev Med Hyg. 2018 Mar;59(1):E14–9. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.1.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]