Abstract

A core curriculum is an essential step in development knowledge, competences and abilities and it defines educational content for the specialized area of practice in such a way that it can be delivered to new professional job. The Health City Manager core curriculum defines the strategic aspects of action to improve health in cities through a holistic approach, with regard to the individual, and a multi-sectoral approach, with regard to health promotion policies within the urban context. The Health City Manager core curriculum recognizes that the concept of health is an essential element for the well-being of a society, and this concept does not merely refer to physical survival or to the absence of disease, but includes psychological aspects, natural, environmental, climatic and housing conditions, working, economic, social and cultural life - as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). The Health City Manager core curriculum considers health not as an “individual good” but as a “common good” that calls all citizens to ethics and to the observance of the rules of civil coexistence, to virtuous behaviours based on mutual respect. The common good is therefore an objective to be pursued by both citizens and mayors and local administrators who must act as guarantors of equitable health ensuring, that the health of the community is considered as an investment and not just as a cost. The role of cities in health promotion in the coming decades will be magnified by the phenomenon of urbanization with a concentration of 70% of the global population on its territory.

Keywords: urban health, public health, Health City Manager, core curriculum

Introduction

The concept of health is essential to the well-being of a society. This concept, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), relates not merely to physical survival or the absence of disease, but includes psychological factors, natural, environmental, climate and housing conditions and working, economic, social and cultural life. Cities play an important role in health promotion owing to the phenomenon of urbanisation, with 70% of the world’s population living in urban areas.

The EU Committee of the Regions during its 123rd plenary session, 11-12 May 2017, approved the own-initiative Opinion “Health in cities: the common good”. The Opinion calls for more effective and responsive multilevel governance to improve health policy and design a fair, shared, harmonious urban system and suggest evaluating the benefits of establishing the post of a healthy city manager and it suggested that cities which do not yet have such a service should evaluate the potential benefits and costs of establishing the post of a HEALTH CITY MANAGER, who would interpret the needs expressed by the city and guide the improvement process in synergy with local authorities by aligning their policies and ensuring their implementation.

In December 2017, Italian Minister of Health and President of Italian Municipalities Association (ANCI) during the G7 side event signed the Urban Health Roma Declaration. The declaration has underlined the necessity of a strong alliance between Municipalities, Universities, Health Centres, Research Centres, Industry and Professionals to study and monitor the determinants of citizens’ health at an urban level and it suggested in the same time the creation of a HEALTH CITY MANAGER figure, able to guide the process of health improvement in urban areas in synergy with local and sanitary administrations.

Health City Institute, in partnership with EUPHA-Urban Health and WFPHA, has developed a core curriculum to define the HEALTH CITY MANAGER knowledge, competences and ability.

Learning degree and professional profile

The HEALTH CITY MANAGER must have acquired transversal and interdisciplinary knowledge in:

- promotion of health and well-being, prevention through the adoption of correct lifestyles of communicable and non-communicable diseases typical of urban areas, in synergy and collaboration with the Authorities responsible for Public Health and Prevention, as well as the Health Professions of the territory;

- assessment of the social and psychological impact of urban life on the quality of life of the citizen with specific attention to situations of greater fragility and to the weak categories of the population in order to achieve improvement;

- city architecture, urban planning and territorial planning, both in terms of the functionality of the city areas and the activation and coordination of participation processes, together with the ability to read, integrate and coordinate the plans aimed at governing the territory and transforming urban contexts;

- capacity for political-administrative dialogue at the various institutional levels, in respect of mutual prerogatives, and interaction with the informal / horizontal levels for the management of the city;

- management of relations for the finalization and measurement of public policies implemented according to adequate timelines and criteria for the replicability and scalability of the project.

The Health City Manager gains professional skills in public health management, sociology and psycho-sociology of communities, urban architecture and control in reducing social and health inequalities.

Duration of the course is determined in University Educational Credits (CFU): each CFU corresponds to 25 hours of student learning. Being a highly theoretical learning, each CFU corresponds to 8 hours of lectures and 17 hours of individual study. The duration of the course will be 80 hours of frontal teaching for a total of 250 hours of student learning and 10 CFU.

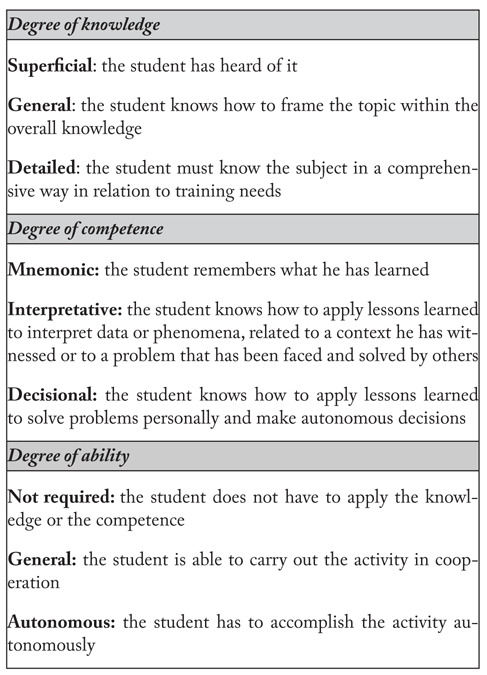

Degrees valid for access to the course are Master’s Degree (MD) achieved in the fields pursuant to Ministerial Decree 22 October 2004, No. 270; Master’s Degree (LS) obtained pursuant to Ministerial Decree of November 3rd 1999, n.109, to the previous equivalent; Diploma (DL) referred to the previous equivalent regulations; foreign equivalent qualifications equivalent. (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Learning degrees

Knowledge, competences and abilities of the Health City Manager

The following table 1 identifies ten priority objectives on Urban Health, the related activities and the knowledge, competences and abilities to be required to the Health City Manager.

Table 1.

Health city manager – core curriculum

| Objective | Activities | Knowledge | Competences | Abilities |

| 1. Health and urban public policies: innovative models of governance, multilevel and multidisciplinary |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required |

|

General | Interpretative | General | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous | |

| 2. Literacy and accessibility to information and health education, including in schools |

|

General | Interpretative | General |

|

General | Decisional | Autonomous | |

|

Detailed | Interpretative | Not required – charged to the decision maker | |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required – charged to the decision maker | |

| 3. Healthy lifestyles in the workplace, in large communities and in families |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required – charged to the decision maker | |

| 4. Food and nutritional culture |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous | |

| 5. Access to sports and physical activity practices for all citizens |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

| 6. Urban transport oriented to slow and sustainable mobility and active transport according to a Walkable City model |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

| 7. Strategies for urban and architectural planning aimed at promoting and protecting health |

|

General | Interpretative | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

General | Interpretative | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Not required | |

| 8. Primary prevention and chronic diseases |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous | |

| 9. Social Inclusion |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required | |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required | |

|

General | Interpretative | Not required | |

| 10. Monitoring of health data |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker | |

|

Detailed | Decisional | Autonomous – interaction with political decision maker |

Conclusion

The function of Health City Manager is the product of a wider consideration process started by the Health City Institute think tank on the main issues of its surveys, namely health in cities and the impact of urbanization on health determinants.

What clearly emerges from this consideration is the need to adopt a new interpretation paradigm, which takes into account a multidisciplinary approach to this issue and the need to achieve a complete involvement at level of local institutions, represented by Administrations and Health Units. These institutions can have a faster and deeper impact on the quality and on the lifestyles of citizens through goal-oriented public policies. New welfare and care models should therefore be identified and promoted within the territorial administration culture.

All institutional and decision-making levels must develop a deeper awareness of the urgency required by the issue of health in urban areas. In order for this to happen, the Health City Institute, in cooperation with EUPHA-Urban Health and WFPHA, has identified in Health City Manager the most appropriate profile to guide cities towards a “Health City” model, contributing to increase the administrative skills of the Authorities and to develop innovative and inclusive solutions to meet the health and welfare requests by citizens.

It is a professional profile the establishment of which has been endorsed also at European level, also through the own-initiative opinion “Health in cities: common good” adopted by the EU Region Committee (May 2017) and the positive feedback by the European Health Commissioner on the occasion of the III Health City Forum of Rome (July 2018). The Health City Institute, together with the project partners EUPHA (European Union Public Health Association - Urban Public Health Section) and ANCI (National Association of Italian Municipalities), has, therefore, on the basis of this, designed the learning profile of the Health City Manager and created the relevant training course.

The aim is to train a professional in management skills in public health, in community sociology and psycho-sociology skills and in urban architecture skills as well as in skills to reduce social and health inequalities.

To this end, the methodology, which led to the development of the core curriculum of the Health City Manager, implied the participation of highly-skilled experts in each of the area of expertise and the sharing of a multidisciplinary approach which would enable to achieve a synthesis as satisfactory and comprehensive as possible.

As a matter of fact, the course is to be considered as a postgraduate course useful to develop a professional who can be part of the Mayor’ staff and to develop those skills and competencies which are however limited and functional to the goals in the remit as indicated in the programming document of the Municipal Administration with which the Health City Manager shall interface. The Health City Manager perfectly integrates with political and technical colleagues there may be in the PA staff since her/his primary task will be to calculate and describe the impact on health and wellbeing of citizens of each resolution, transversally, making it explicit (in writing) and clear to policy makers and field operators. Coordination and periodic alignment of actions put in place is a main goal to be achieved through meetings from large to small scale, including external opportunities of presenting them to the public in such a way that community understands and gains in awareness. Thanks to specific competences in project management for health, plans eventually adopted by Municipalities (i.e. SUMPs, Traffic Plans, Climate Neutral Plans, PEBAs - i.e. plans to eliminate architectural barriers, Urban Planning Strategies, AI applications or data sharing plans) converge in a common shared vision to build up a “health city”. The contribution and the value added provided by this figure can improve the relations and performance of local public administrations with the health units in the territory thereby reconciling and somehow overcoming the historically very deep separation in Italy between the social and the healthcare sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank ANCI (National Association of Italian Municipalities), Urban Public Health Section of the European Public Health Association (EUPHA), World Federation of Public Health Associations (WFPHA), CITIES CHANGING DIABETES for the support to the initiative.

Special thanks to the experts of the “Health City Manager working group”: Cristina Bargero (C14+), Giuliano Barigazzi (Bologna Municipality), Daniele Biagioni (Italian WHO Healthy Cities Network), Michele Carruba (University of Milan), Annamaria Colao (University of Naples), Alessandro Cosimi(C14+), Giuseppe Costa (University of Turin), Roberta Crialesi (ISTAT), Franco D’Amore (i-com), Stefano Da Empoli (i-com), Maria Luisa Di Pietro (University Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Rome), Francesco Dotta (University of Siena), Bernardino Fantini (University of Geneva) , Fabio Fava (University of Bologna), Furio Honsell (University of Udine), Renato Lauro (IBDO Foundation), Livio Luzi (University of Milan), Simona Frontoni (University of Roma Tor Vergata); Roberta Gaeta (Naples Municipality), Daniela Galeone (Italian Ministry of Health), Antonio Gaudioso (CittadinanzAttiva), Ezio Ghigo (University of Turin),Francesco Giorgino (University of Bari), Vito Lepore (IRES Puglia), Daria Maistri (Milan Municipality), Giulio Marchesini (University of Bologna),Eleonora Mazzoni (i-com), Antonio Nicolucci (CORESEARCH), Steffen Nielsen (Cities Changing Diabetes), Stefania Pascut (Udine Municipality), Uberto Pagotto (University of Bologna), Paolo Pandolfi (AUSL of Bologna), Roberto Pella (Parliamentary Intergroup for Quality of Life in the City), Gian Marco Revel (Politecnico University of Marche), Chiara Rossi (CORESEARCH), Daniela Sbrollini (Parliamentary Intergroup for Quality of Life in the City), Federico Serra (Cities Changing Diabetes), Gaetano Settimo (ISS), Roberta Siliquini (University of Turin), Angela Spinelli (ISS), Fabio Sturani (C14+), Angelo Tanese (ASL Roma1), Paolo Testa (ANCI), Simona Tondelli (University of Bologna), Ketty Vaccaro (CENSIS), Simone Valiante (C14+), Stefano Vella (University Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Rome) , Anne Marie Wolkmman (UCL), Francesco Zambon (WHO Europe), Maria Cristina Zambon (Bologna Municipality), Tobia Zevi (ISPI).

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.WHO. Hidden Cities: Unmasking and overcoming health inequalities in urban settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health City Institute, Manifesto Health in the Cities common good. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Committee of Region, 123rd plenary session, Opinion, Health in cities: the common good; 11-12 May 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO, Copenhagen Consensus of Mayors. Healthier and happier cities for all; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5.G7 Side Event, Roma Urban Health Declaration; 11 December 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health City Institute, Creating the World of tomorrow,4th Health City Forum, Health City Manager: Core Competences In Urban Health Management, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision. Rep. Departments of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division, Mar. 2010 Web [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography. Rep. no. 43738. The World Bank, 2009. Web 8 Feb. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban World: Mapping the Economic Power of Cities. Rep. McKinsey Global Institute, Mar. 2011. Web. 8 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaeser Edward. “Cities: Engines of Innovation.” Scientific American, 17 Aug. 2011. Web 9 Feb. 2012. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0911-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaeser Edward. “Triumph of the City [Excerpt].” Scientific American, 17 Aug. 2011. Web 9 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacione M. Urban Geography: A Global Perspective. New York: Routledge; 2001. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Energy Outlook 2008. Rep. International Energy Agency, 2008. Web 9 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Outlook on the Global Agenda 2011. Rep. World Economic Forum, June 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global Risks 2012. Rep. World Economic Forum, June-July 2012. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satterhwaite David. Climate Change and Urbanization: Effects and Implications for Urban Governance. Rep. United Nations Secretariat: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 27 Dec. 2007. Web. 11 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matuschke Ira. Rapid Urbanization and Food Security: Using Food Density Maps to Identify Future Food Security Hotspots. Rep. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2009. Web. 11 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Technology Trends.” ABI Research. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill Dan. “The Adaptive City.” City of Sound, 7 Sep. 2008. Web 11 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaeser Edward L. “E-Ties That Bind.” Economix Blog. New York Times, 1 Mar. 2011. Web 11 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.“Check out Zynga’s Zany New Offices.” CNN Money. Cable News Network. Web. 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gansky Lisa. The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing. New York, NY: Portfolio Penguin; 2010. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 23.“Climate: C40 Cities’ Aggarwala Says Local Governments Can Lead the Way on Climate Action.” E&E TV, 27 July 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brockman John. “Why Cities Keep Growing, Corporations And People Always Die, And Life Gets Faster.” Edge: Conversations on the Edge of Human Knowledge. 23 May 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehrer Jonah. “A Physicist Solves the City.” New York Times, 17 Dec. 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.A Unified Theory of Urban Living. Rep. Macmillan Publishers Limited, 21 Oct. 2010. Web. 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.“Geoffrey B. West: Why Cities Keep on Growing, Corporations Always Die, and Life Gets Faster.” Seminars About Long-Term Thinking. The Long Now Foundation, July-Aug. 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guterl Fred. “Why Innovation Won’t Defuse the Population Bomb.” Scientific American, 31 Oct. 2011. Web 02 Mar. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Estries Michael. “Top Five Most Sustainable Cities in the World.” Ecomagination.com. 29 Nov. 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.“10 Best Cities for the Next Decade.” Kiplinger Personal Finance. July 2010. Web 02 Mar. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.“CFP: Intercity Networks and Urban Governance in Asia.” Center for Southeast and Asian Studies. 22 Aug. 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 32.“Joint Initiative on Urban Sustainability (JIUS).” Environmental Protection Agency. Web. 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clay Jason. “Precompetitive Behaviour: Defining the Boundaries.” The Guardian, 02 June 2011. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 34.“City Mayors: Eurocities Report on City Branding.” Eurocities. Web. 10 Feb. 2012. 31 Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. [New York] Random House, 1961 Print [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kermeliotis Teo. “Hacking the city for a greener future.” CNN Tech. Web 02 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.West Harry. “Why Don’t Regular Joes Care About Sustainability?” Co.Design. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.“Urbanization and Megacities in Emerging Economies.” GlobeScan/SustainAbility, 10 Feb. 2010. Web. 02 Mar. 2012. “Trendwatching.com’s February 2011 Trend Briefing Covering CITYSUMERS.” Trendwatching.com. Web 11 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 38.“Can Cities Build Local Developmental Strategies? Some Surprising Good News from Colombia.” From Poverty to Power by Duncan Green. Oxfam International. Web 10 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duranton Gilles, Diego Puga. Nursery Cities: Urban Diversity, Process Innovation, and the Life-cycle of Products. CEPR Discussion Paper 2376. American Economic Review. Feb. 2000. Web. 14 Feb. 2012 [Google Scholar]