Abstract

The pandemic caused by SARS-CoV2 has stressed health care systems worldwide. The high volume of patients, combined with an increased need for intensive care and potential transmission, has forced reorganization of hospitals and care delivery models. In this article, are presented approaches to minimize risk to Otolaryngologists during their patients infected with COVID-19 care. We performed a narrative literature review among PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases, searching for studies on SARS-CoV2 and Risk Management. Standard operating procedures have been adapted both for facilities and for health care workers, including the development of well-defined and segregated patient care areas for treating those affected by COVID-19. Personal protective equipment (PPEs) availability and adequate healthcare providers training on their use should be ensured. Preventive measures are especially important in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, as the exposure to saliva suspensions, droplets and aerosols are increased in the upper aero-digestive tract routine examination. Morever, the frequent invasive procedures, such as laryngoscopy, intubation or tracheotomy placement and care, represent a high risk of contracting COVID-19. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: COVID-19, Risk Management, Personal protective equipment, SARS-CoV2, Head and Neck Surgery

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed us an unprecedented reflection and changing of hygienic habits and sanitation procedures, outside and inside the hospital. Italy has been one of the first countries to face this challenge.

Fatalities from patients who tested positive for COVID-19 in Italy are summarized in the following chart, based on data from the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS) (Table 1) (1).

An increased number of fatalities in a country is likely related to differences in the number of performed swab tests, the high number of older people (Italy is the second in the world after Japan), and high density of positive patients, with small areas experiencing larger clusters (as happened in Lombardia, in northern Italy).

Overall, about 40% of Italian doctors who died were family doctors, while 25% were specialists with a high risk of infection due to involvement of the respiratory tract and mucosa. The most involved specialities comprehend pneumology, anesthesiology, infectious disease, otolaryngology, ophthalmology and dentistry (1, 2). The transmission of SARS-CoV2 occurs through close contact (less than 2 meters) by exposure to droplets expelled by coughing, sneezing, or speaking. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) cannot penetrate the skin, but it can penetrate all exposed mucous membranes, including the eyes (3-5).

The experience gained during the pandemic provided evidence about risk management (6,7, 38). Anyway, no unique consensus for diagnostic and management has been internationally provided. This is reflected in the absence of unique and internationally approved indications for an oropharyngeal swab, the actual diagnostic gold standard. A European and Global vision is still lacking, and management is left to National Health Institutes or single Centers administration.

By considering the current epidemiological situation and infection trends, controlling the COVID-19 pandemic requires the adoption of precise risk management strategies aimed to reduce contamination between infected individuals and health workers (9).

Risk management

Proactive steps must be taken in anticipation of the trigger and adverse events, represented by a spread of contagion within the hospital among patients, health workers and caregivers (10).

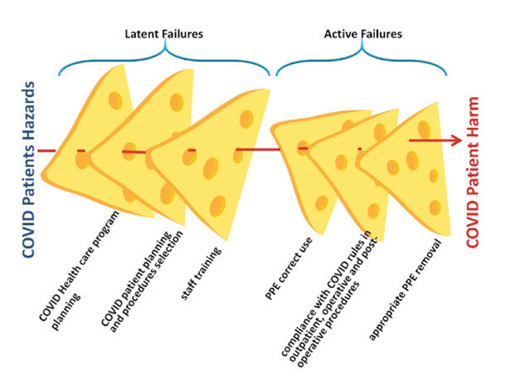

Risk management strategies should follow Reason’s “Swiss cheese model” (Fig. 1) to identify and correct systematic and procedural failures. Assessing these risks permits to recognize barriers, including the appropriate removal of PPE, which can prevent the occurrence of a triggered adverse event (11).

Figure 1.

Modification of Reason’s diagram according to the clinical risk of harm for COVID-19 patients and for contamination of healthcare staff, as obtained by sum of latent and active errors.

Latent errors depend on structural and management filter errors such as lack of strategic planning for the COVID-19 emergency, according to reorganization of logistics, activities and procedures and staff training on rules and the use of PPEs. Active errors are performed individually by the operator, i.e., incorrect use of the PPE devices and their removal not in accordance with the clean and the dirty identified paths, as well as incorrect compliance with the outpatient and surgical procedures rules that COVID-19 ENT patients impose and are described in this article.

Reorganization of hospitals and clinics is essential during the pandemic. In order to reduce interpersonal contacts, social distancing measures should be applied in ENT wards, including limitation of hospitalization to selected surgeries and urgencies, after assessing COVID-19 negativity with double negative RNA- PCR (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal) swab tests, and respecting the adequate measures of prevention in facilities (room ventilation, the distance between beds). The access to the ward should be limited to one caregiver only in case of minor or not self-sufficient patients. Moreover, telephone interviews should be preferred both with patients, whenever an immediate physical examination is not essential and with relatives of hospitalized patients (4, 10, 16, 17,18).

Moreover, health care staff should be aware of the correct use of PPEs as fundamental instruments to protect themselves and patients. They should be trained on the correct procedure, as described in WHO guidelines, to appropriately dress and, even more critical, remove PPEs without contamination in specific areas under the supervision of trained staff. Moreover, healthcare workers suspected to be exposed or infected will need to be quarantined and treated with established procedures.

Preventive and control measures are essential: maintaining good hand hygiene; avoiding contact with eyes, mouth, or nose; and above all, inside the hospital, the use of PPEs including gloves, medical masks, goggles/face shields and gowns in order to protect the health care team and the patients (4, 15).

During April, the stock of PPE, in particular masks and respirators, was often insufficient to meet the need because of the limited capacity of production and the massive demand due to misinformation and panic buying. Also, despite the pandemic spread and gravity seems to be much lower than the beginning, a new wave is expected starting from autumn 2020. That’s why it is mandatory to limit PPEs waste and improve the information about their correct use, in order to increase their availability (15).

Safety procedures in otolaryngology during the covid-19 pandemic: clinical setting

The pandemic of COVID-19 is heavily interfering with ordinary medical practices and surgeries.

Otolaryngology is one of the most affected specialities because routine examination and procedures place physicians close to patients’ upper respiratory tract. During the inspection of the oral cavity and the oropharynx, as well as in rhinoscopies, laryngoscopies and tracheostomy tube replacements, doctors and health workers are in direct contact with saliva and mucous suspensions. This is due to being only 20-30 cm far from the patient’s face, performing manoeuvres that potentially cause cough or sneeze as a physiological reflex (17-21). Besides, COVID-19 infections frequently present with respiratory symptoms involving the upper airway tract. Thus a swab test should be performed before ENT evaluation. In case of possible positive patients, the Italian Higher Institute of Health (ISS) recommends to the healthcare team to wear surgical masks, disposable gowns, gloves, and goggles; when performing aerosol-generating procedures. ISS recommends to use FFP2 (filtering facepiece) or FFP3, disposable and water-repellent gowns, gloves, and protective goggles (20).

Moreover, in order to reduce patient exposure to contamination, all non-urgent examinations should be postponed by telephone contact. Delayable evaluations include benign and chronic diseases, oncologic controls, pediatric evaluations, and in every case, the presence of new-onset symptoms should be excluded. (20-23) Patients should be informed on the need to access sanitary facilities by wearing a surgical mask (18).

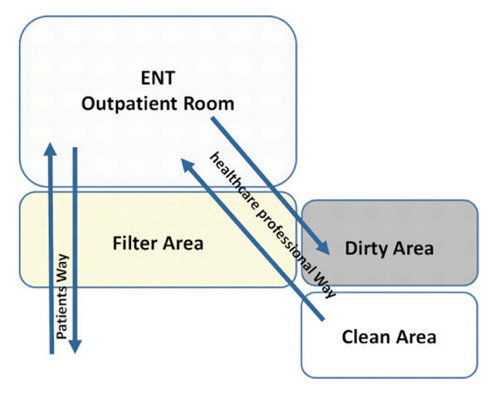

As the ENT evaluation creates aerosols from the respiratory secretion, the outpatient room should be considered a potentially contaminated area (19). Therefore, the outpatient room must be structurally isolated by creating controlled access for the user through a filter area where the patient will enter wearing a mask (20, 21). The healthcare team should dispose of a clean area, dedicated to PPE wearing, and a separated dirty area for safe removal and elimination of contaminated PPE as described in the model in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Basic model of the structural organization of the patients’ and health workers’ pathways in order to contain as much as possible the potential spread of the virus in ENT daily clinical practice during epidemic.

Safety procedures in otolaryngology during the covid-19 pandemic: operating room setting

As for medical examination, surgery experienced substantial changes, with drastic cuts of operating room activity. As remarked and described by Pearlman AN et al., protocols created during COVID-19 pandemic reflected a “safety first” philosophy (38). This was due to avoiding patient’s contamination entering the hospital for non-urgent procedures, and because of the use of operating room ventilators to support COVID-19 intubated patients in many hospitals (4, 13, 34). In Wuhan, the most affected medical personnel were anesthesiologists, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists because of the close contact between nasal, oropharyngeal cavities and the eyes (32). For these professionals, during surgical procedures, the risk of intraoperative transmission of COVID-19 is very high. For these reasons, a growing number of Universities and surgical associations created guidelines, suggesting only performing emergency surgeries or, at least, those that cannot be delayed, such as oncological surgeries (18, 21, 34).

In particular, endonasal endoscopic surgery and skull base surgery are considered to be high-risk procedures, since the use of debriders and drills within the nasal cavity produced aerosol droplets (30), as described in the Chinese experience (29). Many authors reported positive COVID-19 cases among surgeons and operating room team after an endoscopic nasal surgery (31). Also, pediatric surgery, except for emergent procedures, should be postponed, as the pediatric population can contract COVID-19 even if the great majority of children presents with mild or no symptoms (4).

The Italian Society of Otolaryngology (SIO), following the British ENT Association instructions, recommends the use of PPEs during COVID-19 patients’ surgery, i.e. double disposable and water-repellent gowns, double gloves, FFP3 or N99 type masks, or, if not available, FFP2 or N95, eye protection, surgical cap, and proper shoes/boots. As far as eye protection is concerned, in order to protect from conjunctival penetration, the use of a disposable respirator and safety goggles, or a full-face respirator is suggested. Safety goggles with a rubber air seal provide a tighter air barrier (27, 28). Before the operation, it is recommended to test for COVID-19 through an oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal swab twice (4 days before and 48 hours before surgery). If the test cannot be performed, the patient should be considered as positive. If the test is negative and the patient is asymptomatic, there is no particular instruction for the use of PPE, but the number of staff people and the length of surgery must be reduced. If the patient is positive, the surgery should be delayed, and the test should be repeated a few days later unless an emergent procedure is needed (33-35).

Special isolating zones are fundamental, and so is an isolated operating room. A hostile pressure transfer vehicle, or at least a unique passageway, should be used to move patients.

During intubation, an extra layer of gloves is necessary. When administering anaesthesia, it is preferable to do a rapid induction, moderate sedation and good muscle relaxant in order to avoid a choking cough. Strict monitoring should be performed throughout the entire operation (8).

Tracheostomy is classified as a high-risk procedure in COVID-19 patients since it is an aerosol-generating procedure: the need for tracheostomy must consider both benefits and risks for the patient and staff (25, 26, 36, 37). Different medical societies have created their own recommended procedures to guide medical staff and to minimize risks for the patient. It is fundamental to create a dedicated team, well-informed about the recommended techniques and ability to apply them to the workplace. The presence of two head and neck surgeons and one anesthesiologist (a COVID team) is mandatory (15, 24).

The following table (Table 2) sums up the instructions of two societies and offers a list of things to do during the days before surgery, during surgery, and after surgery.

Table 2.

How health care professionals need to plan and do before, during and after the tracheostomy in COVID-19 pandemic

| Planning (Week of Surgery) |

|

| Day of Surgery |

|

| During Surgery |

|

| After Surgery |

|

Conclusions

In the current pandemic, as well as in any other medical emergency, the most crucial goal is to reduce the spread of the virus, especially within hospitals, where every contact represents a risk for patients and staff. It is necessary to prevent transmission of the disease from patients to medical staff and also from medical staff to patients. In case of a new wave, prompt behaviour with correct precautions are mandatory. For these reasons, in these circumstances, limiting nonessential activities and surgeries is needed.

Hospitals must prevent the contamination of their medical staff and health care personnel in order to decrease connected clinical risks and the relative risk of contagion among the team of practitioners. If the contagion expands to the team and determines the reduction of their operation, sufficient health care for citizens is not guaranteed, also leading to high direct and indirect costs.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

Verification:

All authors have seen the manuscript and agree to the content and data. All the authors played a significant role in the paper.

Ethical Statement:

The article doesn’t contain the participation of any human being and animal.

References

- 1.Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Epidemia COVID-19. Aggiornamento nazionale 4 Settembre. 2020 Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federazione Nazionale degli Ordini dei Medici Chiurghi e degli Odontoiatri. Elenco dei Medici caduti nel corso dell’epidemia di Covid-1. Available at: https://portale.fnomceo.it/elenco-dei-medici-caduti-nel-corso-dellepidemia-di-covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS COVID-19 n. 2/2020Rev. Indicazioni ad interim per un utilizzo razionale delle protezioni per infezione da SARS-COV-2 nelle attività sanitarie e sociosanitarie (assistenza a soggetti affetti da COVID-19) nell’attuale scenario emergenziale SARS-COV-2. Aggiornato al 10 Maggio. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang D, Tou J, Wang J, et al. Prevention and control strategies for emergency, limited-term, and elective operations in pediatric surgery during the epidemic period of COVID-19. World Jnl Ped Surgery. 2020;3:e000122. doi: 10.1136/wjps-2020-000122. doi: 10.1136/ wjps-2020-000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maniaci A, Iannella G, Vicini C, et al. A Case of COVID-19 with Late-Onset Rash and Transient Loss of Taste and Smell in a 15-Year-Old Boy. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e925813. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925813. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McArthur L, Sakthivel D, Ataide R, Chan F, Richards JS, Narh CA. Review of Burden, Clinical Definitions, and Management of COVID-19 Cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(2):625–638. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0564. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasmi A, Noor S, Tippairote T, Dadar M, Menzel A, Bjørklund G. Individual risk management strategy and potential therapeutic options for the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108409. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108409. doi: 10.1016/j.clim2020.108409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement on the issuance of technical guidelines for the prevention and control of the new coronary virus infections in medical institutions (first edition) (in Chinese) Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202001/b91fdab7c304431eb082d67847d27e14.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ministero della salute, Protocollo per il monitoraggio degli eventi sentinella, available http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1783_allegato.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Home care for patients with COVID-19 presenting with mild symptoms and management of their contacts: interim guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.James Reason, The Human Contribution, 2010-Hirelia Srl, Milano, IT; Edizione italiana a cura di Hirelia Edizioni [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzenbach J. R, Smith D. K. The Wisdom of Teams, Harvard Business Review Press. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo WY, Yuan JP, Fu T, et al. Perioperative prevention and control strategies for surgical patients in the context of new coronavirus pneumonia (in Chinese) Chin J Dig Surg. 2020;19:E001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charles Vincent. Patient Safety. Springer-Verlag Italia. 2011 DOI 10.1007/978-88-470-1875-4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Helath Organization, Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages, Interim guidance 6 April 2020, WHO/2019-nCoV/IPC PPE_use/20202 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Infection prevention and control of epidemic-and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e Chirurgia Cervico Facciale, Accesso all’ambulatorio ORL in corso di pandemia da SARS-COV-2. available: https://www.sioechcf.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Accesso-allambulatorio-ORL-in-corso-di-pandemia-da-SARS-COV-2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Givi B, Schiff BA and, Chinn SB. “Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print March 31, 2020].”. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu K, Lai XQ, Liu Z. “Suggestions for prevention of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in otolaryngology head and neck surgery medical staff.”. Zhonghua er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi= Chinese journal of otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery. 2020;55:E001–E001. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-0860.2020.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, et al. Alterations in Smell or Taste in Mildly Symptomatic Outpatients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2089–2090. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Fabbris C, et al. Evolution of Altered Sense of Smell or Taste in Patients With Mildly Symptomatic COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(8):729–732. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1379. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Philips V, et al. Self-reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology. 2020 doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.185. 10.4193/Rhin20.185 doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Spinato G, et al. New onset of loss of smell or taste in household contacts of home-isolated SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(9):2637–2640. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06066-9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06066-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pichi B, Mazzola F, Bonsembiante A, et al. CORONA-steps for tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients: A staff-safe method for airway management. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104682. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104682. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tay JK, Khoo MLC, Loh WS. Surgical considerations for tracheostomy during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. :10. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ENTUK, Aerosol-generating procedures in ENT. available: https://www.entuk.org/sites/default/files/files/Aerosol-generating%20procedures%20in%20ENT_compressed.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e Chirurgia Cervico Facciale, La tracheostomia in pazienti affetti da COVID-19. available: https://www.sioechcf.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/La-tracheostomia-in-pazienti-affetti-da-COVID-19.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 28.ENTUK, COVID-19 Tracheostomy, Framework for open tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. available: https://www.entuk.org/sites/default/files/files/COVID%20tracheostomy%20guidance_compressed.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 29. China Newsweek.View.inews.qq.com/a/20200125A07TT200?uid=&devid=BDFE70CD-5BF1-4702-91B7-329F20A6E839&qimei=bdfe70cd-5bf1-4702-91b7-329f20a6E839. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Società italiana del basicranio, Chirurgia del basicranio durante l’emergenza COVID-19. available: https://societabasicranio.it/altreimg/SIB-raccomandazioni_covid-19.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.ENTUK, Nasal endoscopy and laryngoscopy examination of ENT patients. available: https://www.entuk.org/sites/default/files/files/Nasal%20endoscopy%20and%20laryngoscopy%20examination%20of%20ENT%20patients_compressed.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 32. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-17/europe-s-doctors-getting-sick-like-in-wuhan-chinesedoctorssay?fbclid=IwAR2ds9OWRxQuMHAuy5Gb7ltqUGMZNSojVNtFmq3zzcSLb_bO9aGYr7URxaI . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel ZM, Fernandez-Miranda J, Hwang PH, Nayak JV, Dodd R, Sajjadi H, Jackler RK. Letter: Precautions for Endoscopic Transnasal Skull Base Surgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(1):E66–E67. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa125. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e Chirurgia Cervico Facciale, Attività chirurgica ORL durante la pandemia da COVID-19. available: https://www.sioechcf.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Sala-operatoria-ORL-COVID.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 35.ENTUK, Guidance PPE for patients with emergency oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal conditions whose COVID Status is unknown. available: https://www.entuk.org/sites/default/files/files/BAOMS%20ENT%20COVID%20Advice%20Update%2025%20March%202019%20Final.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 36.Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment. Available at: https://esge.org/documents/Handbook_of_COVID-19_Prevention_and_Treatment.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan JYK, Wong EWY, Lam W. Practical Aspects of Otolaryngologic Clinical Services During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Epidemic: An Experience in Hong Kong. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(6):519–520. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0488. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearlman AN, Tabaee A, Sclafani AP, et al. Establishing an Office-Based Framework for Resuming Otolaryngology Care in Academic Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;194599820955178 doi: 10.1177/0194599820955178. doi: 10.1177/0194599820955178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]