Abstract

Human rabies disease is caused by Rabies Lyssavirus, a virus belonging to Rhabdoviridae family. The more frequent means of contagion is through bites of infected mammals (especially dogs, but also bats, skunks, foxes, raccoons and wolves) which, lacerating the skin, directly inoculate virus-laden saliva into the underlying tissues. Immediately after inoculation, the Rabies virus enters neural axons and migrates along peripheral nerves towards the central nervous system, where it preferentially localizes and injuries neurons of brainstem, thalamus, basal ganglia and spinal cord. After an initial prodromic period, the infection evolves towards two distinct clinical entities, encompassing encephalitic (i.e., “furious”; ~70-80% of cases) and paralytic (i.e., “dumb”; ~20-30% of cases) rabies disease. The former subtype is characterized by fever, hyperactivity, hydrophobia, hypersalivation, deteriorated consciousness, phobic or inspiratory spasms, autonomic stimulation, irritability, up to aggressive behaviours. The current worldwide incidence and mortality of rabies disease are estimated at 0.175×100,000 and 0.153×100,000, respectively. The incidence is higher in Africa and South-East Asia, nearly double in men than in women, with a higher peak in childhood. Mortality remains as high as ~90%. Since patients with encephalitic rabies remind the traditional image of “Zombies”, we need to think out-of-the-box, in that apocalyptic epidemics of mutated Rabies virus may be seen as an imaginable menace for mankind. This would be theoretically possible by either natural or artificial virus engineering, producing viral strains characterized by facilitated human-to-human transmission, faster incubation, enhanced neurotoxicity and predisposition towards developing highly aggressive behaviours. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: rabies virus, rabies disease, epidemiology, zombie

The Rabies virus

Rabies disease is mostly sustained in humans by Rabies Lyssavirus, a virus belonging to the large family of Rhabdoviridae, comprised within the Mononegavirale order (1). It is conventionally assumed that the original virus shall have evolved in Old World bats, which then shifted to carnivores and spread globally, more or less resambling what has more recently happened with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus is characterized by a bullet-shaped structure, sizing approximately 75×200 nm, and is substantially divided in two parts, encompassing a structural (i.e., the viral envelope) and a functional (i.e., the ribonucleoprotein; RNP) unit. The ~12 kd RNA of the virus contains five major genes, encoding five corresponding viral proteins (1). Briefly, (i) the N gene encodes the nucleoprotein encapsulating both viral and unsegmented negative-stranded RNA, (ii) the P gene encodes a phosphoprotein involved in transcription and replication activities, as well as in mediating interplay with cellular proteins during neural transportation (see below), (iii) the M gene encodes a matrix protein, (iv) the G gene encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein, which mediates binding during initial infection and seems to be the major antigenic domain responsible for generation of neutralizing antibodies and, finally, (v) the L gene encodes a RNA polymerase (1). The viral capsid is typically surrounded by host cell-originating plasma membrane, strictly interacting with the matrix protein and the transmembrane glycoprotein. Overall, Rabies viruses are divided into two major phylogroups, accounting for a total number of up to 14 different genotypes (2). Among these, genotype 1 seems to be the most prevalent, and also that causing the largest number of human infections (3).

Physiopathology of Rabies virus infection

Although all the precise mechanisms involved in the physiopathology of Rabies virus infection have not been thoughtfully discovered and defined so far, several important aspects can be summarized. The more frequent means of Rabies virus transmission in humans is through bites of infected mammals which, lacerating the skin, directly inoculate virus-laden saliva into underlying tissues. Dogs are the most frequent vehicles of infection in poor countries, whilst virus inoculation by other mammals such as bats, skunks, foxes, raccoons and even wolves has been reported in developed countries (4). The risk of virus inoculation through bites is highly variable (i.e., between 5-80%), depending on bite severity, animal species, virus concentration, amount of saliva inoculation and so forth, but remains consistently higher than after simple scratchs (i.e., 0.1-1.0%) (1). In particular, a recent study reported that the risk of virus inoculation by animal bite exposure is the highest for skunks, followed by bats, cats and dogs (5). In general, bites involving the face, neck or hands expose the patient to the highest risk of contagion, especially when the lesion is accompanied by profuse bleeding (1). Since Rabies virus is actively present in many human biological fluids, especially cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), saliva, urine and tears, as well as at the nape of neck containing hair follicles (6), an accidental and involuntary human-to-human transmission is theoretically possible (7,8), as also revealed by publication of a number of paradigmatic case reports (9-12). Nonetheless, cases of rabies contamination through direct contact with blood of infected humans have not been described so far, whereby the virus seems to follow a prevalent intra-neuronal localization, and a clear viraemia is hence probably absent in mammals (13). Moreover, the Rabies virus can be very rapidly inactivated by sunlight (i.e., ultraviolet rays) and heat exposure, so that its chances of survival outside the host are extremely limited. It seems reasonable to conclude that the cumulative risk of human-to-human infection appears definitely low, except in the case of direct inoculation of human saliva (e.g., through voluntary or involuntary bite) of infected individuals (13).

Immediately after inoculation, the virus enters neural axons of sensory and motor nerves with an endosomal transport pathway, and then migrates along peripheral nerves (through fast axonal transport system) towards the CNS, with a speed estimated at approximately 8-20 mm/day (4). According to this velocity of propagation, the incubation period of rabies disease depends on the site of inoculation, whereby in patients who have been infected at distant sites (i.e., arms or legs) the virus would need longer time to reach the CNS than in those bitten on face or neck. Although no clear receptor mechanism has been elucidated so far, it seems that nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAchR) and neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) may play a role in concentrating virus particles at the neuromuscular junction and providing a more efficient transportation within the intracellular space. Once the intact virions have reached the CNS (thus producing pathognomonic cytoplasmic inclusions, known as “Negri bodies”), viral replication starts by transcription of viral genome by P-L polymerase and further assembly of new viruses, especially in dorsal-root ganglia and anterior-horn cells. The virus then propagates throughout the CNS, principally through plasma-membrane budding, cell-to-cell direct infection or trans-synaptic dissemination, with preferential localization in brainstem, thalamus, basal ganglia and spinal cord (3). Importantly, major damages to the limbic system are those responsible for onsets of the typical emotional and motivational symptoms characterizing patients with viral encephalopathy (2). The cumulative neurotoxicity is perhaps the result of a combination of direct cell damage due to virus replication, as well as to development of immune response and autoimmune reactions against infected neurons. Importantly, the huge cytokines production that accompanies CNS infection generates a strong impact on hippocampus and other limbic-system functions, thus impairing electrical cortical activity, hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin metabolism (4). Later in the course of disease, Rabies virus returns to the periphery by means of intra-axonal transport, with enhanced tropism for salivary and lacrimal glands (14).

Pathology and clinics of Rabies virus infection

The so-called prodromal stage typically initiates when the virus propagates from peripheral nerves to dorsal-root ganglia (i.e., triggering neuropathic pain), up to the CNS. Along with prickling or itching sensation at the site of the original bite, the initial symptoms appear relatively non-specific, mimicking an influenza syndrome, and thus encompassing fever, general weakness and headache (1). After this initial period, whose length is somewhat variable (i.e., between 2-10 days), the infection can then evolve towards two distinct clinical entities, encompassing encephalitic (i.e., “furious”; ~70-80% of cases) and paralytic (i.e., “dumb”; ~20-30% of cases) rabies (4).

The former subtype (i.e., encephalitic) of rabies is also the most severe, whereby the vast majority of these patients die within 1 week of onset, and display fever, hyperactivity aggravated by thirst, fear, light, noise and other external stimuli. Within 24 hours from the onset of the first symptoms the patients also develop hydrophobia, hypersalivation, fluctuating consciousness, hallucinations, phobic or inspiratory spasms (often accompanied by fearful facial expressions), along with signs of autonomic stimulation. Importantly, the impaired serotonin neurotransmission due to injured brainstem cells is frequently accompanied by marked agitation and irritability, and can occasionally evolve toward aggressive behaviours (15). Throughout this period, patients shall be preferably isolated and sedated, to prevent that they may involuntarily injury, or even contaminate, relatives and/or the healthcare staff (16). The mental status varies, characterized by almost normal periods alternated with severe agitation or depression, up to consciousness deterioration and coma. Seizures are not very frequent, but can occasionally develop in pre-terminal stage. Hematemesis may be present in nearly half of the patients few hours before death, which can also occur for respiratory, cardiac and circulatory arrest during severe spasm episodes (4). Taken together, these signs and symptoms would contribute to associate a rabid patient with the traditional image of a “Zombie”, as originally depicted by George A. Romero in his notorious 1968 movie “The Night of the Living Dead” (17), where humans were transformed into aggressive, flesh-eating cannibals after being exposed to radiations of space probe which exploded in the atmosphere while coming back from Venus.

The paralytic, and less frequent form of rabies, is mostly characterized by weakness due to peripheral nerve dysfunction attributable to the combined effect of an autoimmune reaction against the infected cells and activation of immune response against the viruses within the axons (4). Unlike the encephalitic subtype, where brain stem, cerebrum and limbic system are especially affected, this form mainly involves medulla and spinal cord (18). This mostly leads to appearance of symptoms like muscular paralysis and facial diparesis. The CNS involvement develops later in the course of disease, evolves towards coma and is then usually followed by death (4).

Epidemiology of rabies

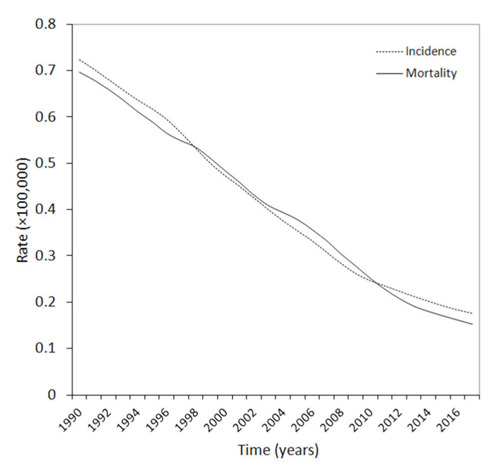

The most updated statistics on rabies epidemiology can be garnered from the database of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2017 (19), which is currently considered the most comprehensive worldwide repository of health-related information (20). The trends of incidence and mortality of this condition over the past 3 decades are reported in figure 1, which clearly shows that both these epidemiologic measures have considerably declined, by approximately 80%, between the years 1990-2017. In 2017 (i.e., the last accessible year in the GBD database), rabies disease has an estimated incidence and mortality of 0.175×100,000 and 0.153×100,000, respectively (i.e., ~13200 cases and ~11500 deaths around the world). Notably, the mortality rate has also contextually declined during the past 30 years, from 96% to 87%, thus mirroring the combination of improved diagnosis and better therapeutic care.

Figure 1.

Epidemiology of Rabies virus disease during the past three decades.

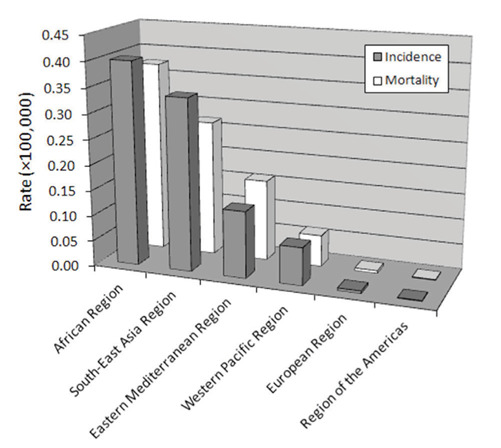

The geographic distribution of rabies disease in the year 2017 is shown in figure 2. The worldwide area with the highest incidence and mortality is Africa, followed by South-East Asia, Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific, whilst the values of both these epidemiologic measures is <0.01×100,000 in Europe and Americas. The highest burden of rabies disease cases described in Africa (i.e., 0.40×100,000) and South-East Asia (0.34×100,000) is clearly dependent on insufficient infrastructure for preventing, diagnosing and rapidly establishing post-exposure prophylaxis, as well as on ubiquity of wild and domestic animals, which enormously magnifies the risk of human contagion (2). Notably, the incidence of rabies disease in Romania (which is - incidentally - the ancestral vampires’ homeland) is over 2-fold higher than in the rest of Europe (i.e., 0.011×100,000 vs. 0.005×100,000). The distinctive geographical localization of rabies disease mirrors that of the socio demographic index (SDI), since the incidence in countries with low SDI (0.445×100,000) is nearly 4-fold higher than in medium SDI countries (0.102×100,000), being approximately 300-fold higher than in high SDI countries (0.002×100,000).

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of Rabies virus disease.

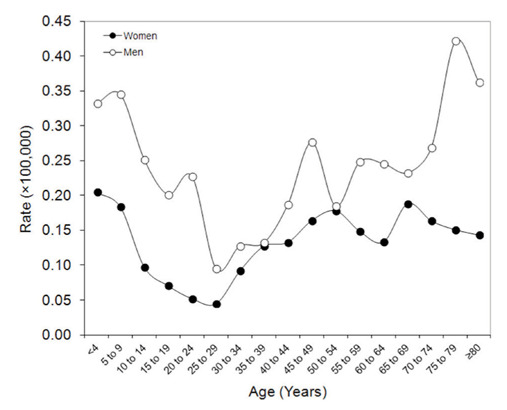

The age and sex distribution of rabies disease is then summarized in figure 3, showing that the overall incidence is nearly double in men than in women (i.e., 0.22×100,000 vs. 0.13×100,000). The epidemiology in men is characterized by an almost triphasic curve, with peaks of incidence in the childhood (i.e., between 0-14 years), in the middle age (i.e., between 40-54 years) and in the elderly (i.e., after 75 years of age), whilst the epidemiology in women seems more homogenous, with an initial peak in childhood, a further decline between 10-29 years and a final (virtually stable) increase throughout adulthood.

Figure 3.

Sex- and age-related epidemiology of Rabies virus disease.

Could Rabies virus become a “Zombie virus”?

The term “rabies” most likely derives from the old Indian root word “rabh”, which stands for “making violence” (21). It is hence not surprising that the most devastating phenotype of encephalitic (“furious”) rabies disease is that of an individual displaying hypersalivation, hydrophobia, paranoia, hyperactivity, hyperirritability and abnormal aggressiveness (4). Interesting evidence has recently been published by a team of scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (22), who demonstrated that a specific sequence within the Rabies virus glycoprotein, which has partial homology with snake toxins, is capable to inhibit the nAchR in the CNS, thus modifying animal behaviours and triggering high excitability and hostility.

The hypothesis of viral infection as primary cause of a “Zombie” transformation (i.e., “zombification”) is not new, since it has already been proposed in both the “Resident Evil” movie series and by “Walking Dead” comics, nearly 20 years ago (23). In the former case, the so-called “Tyrant Virus” (also known as “T-Virus”) was originally developed by the imaginary pharmaceutical company “Umbrella Corporation” in the late 1970s, with the primary scope of eradicating some genetic diseases. Nevertheless, the innate characteristics of the T-Virus persuaded some scientists to promote its conversion into a biological weapon, whereby the pathogen would have been capable to almost irreversibly damage the CSF (especially neurons in frontal lobe, somatosensory cortex and hypothalamus), thus generating a dramatic decline in intelligence and motor functions in the host, but preserving many elementary function, reducing pain responsiveness and amplifying psychotic rage, persistent hunger, and increased aggressiveness (i.e., “zombification”) (17).

Some intriguing cases of “pseudo-zombification” have also been reported in the scientific literature, mostly occurring in Haiti (where the original term “Zombie” was coined), as result of tetrodotoxin and/or Datura stramonium intake (24), or more recently in the US, after mass intoxication with synthetic cannabinoids such as AMB-FUBINACA (25). The risk of a “Zombie emergency” has also been seriously contemplated by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), issuing an official manual entitled “Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic” (26) (Fig. 5), which aims to prepare healthcare and civil resources to handle epidemic threats, among which Zombie infestation is perhaps the most paradigmatic example. This document has then been followed by another guide, endorsed by the US Government, and specifically called “Counter-Zombie Dominance” (27). This second document contains the thoughtful description of how a military strategy shall be established for defending the nation against an imaginable Zombie alert, thus encompassing detailed information on biological characteristics of “enemy force”, on available means for preventing pathogen transmission, as well as on conceivable strategies that shall be planned for preventing collapse of civilized society (27). Therefore, some discernible questions would follow. Specifically, how much human rabies disease overlaps with “zombification”? And, would it be possible that a mutated Rabies virus epidemics (or pandemic) will transform mankind into Zombies?

Figure 5.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) manual “Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic”.

The first important aspect is defining the risk of human-to-human transmission, the mainstay of the imaginary Zombie contagion (28). It has been previously highlighted that bloodborne transmission is very unlikely for rabies disease, whereby viraemia does not seemingly occur with this type of infection. The survival of Rabies virus outside the host is also frankly poor, so that the most probable means of human-to-human transmission would need direct inoculation of the pathogen through bites from infected people (13). Rabies virus detection in saliva of infected humans has been reported as being the highest 2-3 days after the onset of symptoms, remains apparently stable for 2-7 days afterwards, and then apparently declines (29). Throughout the contagious window, it shall hence be assumed that patients with overt rabies disease would be so aggressive against their own kind to feel the uncontrollable instinct to bite them. Although there is only sporadic evidence of rabid patients biting other humans (e.g., a 41-year-old woman died of rabies disease after being bitten by her 5-year-old son, who in turn had developed the pathology after being bitten by a rabid dog) (9), this possibility cannot be straightforwardly excluded. The real incidence of human bites is largely underestimated due to under-reporting, and also because affected people tend to avoid medical care. Nevertheless, current evidence suggests that mammalian bites would account for almost 1% of all emergency department visits, up to 20% of which are attributable to human bites (i.e., 0.2% of all emergency department admission) (30). Therefore, the suggestion that extremely aggressive rabid patients would suffer from an incontrollable instinct to bite other humans, and thus transmitting the infection, remains actual. Interestingly, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC suggests that post-exposure prophylaxis shall be planned for all people with mucous membranes or non-intact skin exposure to potentially infectious body fluids from rabid patients (31), thus implicitly confirming that the risk of human-to-human transmission of rabies disease is not irrelevant.

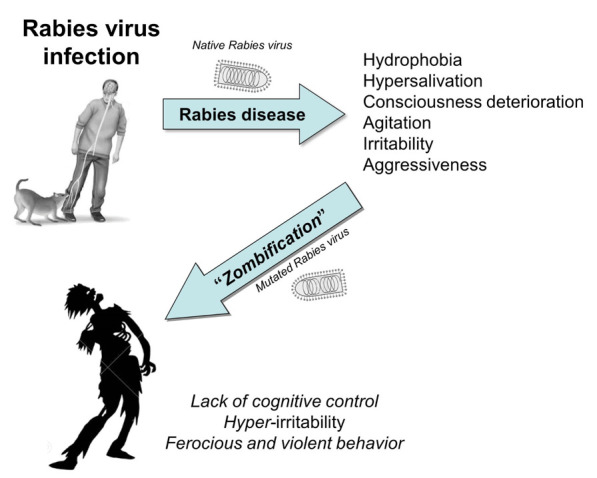

The comparison of the current image of a Zombie with that of a rabid patient is a second import aspect that needs to be accurately scrutinized. As already emphasized, conventional Zombies, as depicted in comics and movies (23), share some similar behaviours with patients infected by Rabies virus. Both undergo a variable degree of consciousness deterioration, which tends to be almost identical in the last stages of rabies disease. Both individuals display also fearful facial expressions, increased hyperirritability and aggressiveness, which can be both substantially accentuated by external stimuli (thirst, fear, light and noise) in rabid patients (Figure 4), and may ultimately evolve toward violent and ferocious behaviours.

Figure 4.

Clinical similarities between encephalic rabies disease and imaginary “zombification”.

That said, it is now widely acknowledged that many viruses are characterized by naturally occurring high mutation rates, which induce constant changes as reliable means for escaping host defences or facilitating their transmission to other susceptible hosts. Rabies virus makes no exception to this rule, as recently described by Wang et al (32), who found a vast array (up to 100) of antigenic variants of this pathogen in a wide range of animal hosts and geographic locations. Notably, even single amino acid mutations in the proteins of Rabies virus can considerably alter its biological characteristics, for example increasing its pathogenicity and viral spread in humans, thus making the mutated virus a tangible menace for the entire mankind (33). Beside the natural evolution of Rabies virus, an equal threat may come from the science of genetic engineering, which would reproduce the theatrical scenario depicted in the movies of the Resident Evil saga (23), and more recently advocated also for COVID-19. By means of genetic engineering, scientists have already developed innovative biological weapons, which would appear more powerful and destructive than their natural counterparts (34). The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, in China, is perhaps the most paradigmatic example (35), whereby many biological features of the pathogen have led some eminent scientists to conclude that the SARS virus might have been produced under laboratory conditions (36). Would a mutated Rabies virus, bearing one or more mutations such as those described by Hueffer et al (22), and hence characterized by facilitated human-to-human transmission, faster incubation, enhanced neurotoxicity and predisposing towards aggressive highly behaviours, become the most lethal biological agent that humans have ever faced?

Conclusions

The Rabies virus, like the vast majority of other pathological microorganisms, attempts to perpetuate itself with general and reservoir host-specific mechanisms, which ultimately confer a considerable epidemiological plasticity. The pace and phenotype of rabies infection are mostly written in the virus genome, whilst transmission is strongly favoured by aggressive behaviours (i.e., a biting inclination) of rabid hosts (37). Despite incidence and mortality of rabies disease have both markedly declined during the past three decades (Fig. 1), and irrespective of whether the genetic code of Rabies virus can be naturally (i.e., by ecological opportunities and viral adaptation) or artificially (i.e., by genetic engineering) modified, we need to think “out-of-the-box”, in that the generation of a “Zombie virus” cannot be firmly excluded according to the currently available biological evidence (38). Wavefront velocity of rabies disease propagation has been calculated in wild animals (e.g., foxes, skunks, raccoons and vampire bats) at around 10-40 km per year (37). However, in densely populated towns, where natural landscape barriers would be minimal, the human-to-human contagion may increase by several orders of magnitude, thus easily assuming apocalyptic proportions and creating a new generation of pseudo-human creatures, who have completely unleashed their already existing part of zombie within (39). In keeping with this conjecture, an interesting simulation of an imaginary Zombie outbreak reveals that most of the US population would turn into Zombies within one week from appearance of the first case, whilst only some remotes zones in Montana and Nevada would remain infestation-free one month afterwards (40).

In conclusion, what has become rather clear so far is that rabies disease is entirely preventable, while encephalomyelitis has never been described in people who had received pre-exposure vaccination or post-exposure booster (41). Therefore, although the transformation of Rabies virus into a “Zombie virus” will always remain a tangible threat surrounding human future (Fig. 1), further efforts shall be made for disseminating a culture of widespread knowledge, prevention and surveillance against this and other potentially devastating viruses (42).

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Consales CA, Bolzan VL. Rabies review: Immunopathology, clinical aspects and treatment. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2007;13:5–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis BM, Rall GF, Schnell MJ. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Rabies Virus (But Were Afraid to Ask) Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:451–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell MJ, McGettigan JP, Wirblich C, Papaneri A. The cell biology of rabies virus: using stealth to reach the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:51–61. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemachudha T, Laothamatas J, Rupprecht CE. Human rabies: a disease of complex neuropathogenetic mechanisms and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:101–9. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaidya SA, Manning SE, Dhankhar P, Meltzer MI, Rupprecht C, Hull HF, Fishbein DB. Estimating the risk of rabies transmission to humans in the U.S.: a Delphi analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:278. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wacharapluesadee S, Hemachudha T. Ante-and post-mortem diagnosis of rabies using nucleic acid-amplification tests. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:207–18. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helmick CG, Tauxe RV, Vernon AA. Is there a risk to contacts of patients with rabies? Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:511–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutta JK, Dutta TK, Das AK. Human rabies: modes of transmission. J Assoc Physicians India. 1992;40:322–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fekadu M, Endeshaw T, Alemu W, Bogale Y, Teshager T, Olson JG. Possible human-to-human transmission of rabies in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 1996;34:123–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolars JC. Should contacts of patients with rabies be advised to seek postexposure prophylaxis? A survey of tropical medicine experts. J Travel Med. 2003;10:52–4. doi: 10.2310/7060.2003.30597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu JY, Pan J, Lu YQ. A case report on indirect transmission of human rabies. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2015;16:969–70. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu XX, Zhu WY, Wu GZ. Rabies virus transmission via solid organs or tissue allotransplantation. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:82. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gongala G, Mudhusudanab SM, Sudarshanc MK, Mahendrad BJ, Hemachudhae T, Wildee H. What is the risk of rabies transmission from patients to health care staff? Asian Biomed. 2012;6:937–939. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mrak RE, Young L. Rabies encephalitis in humans: pathology, pathogenesis and pathophysiology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson AC. Diabolical effects of rabies encephalitis. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:8–13. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warrell M, Warrell DA, Tarantola A. The Imperative of Palliation in the Management of Rabies Encephalomyelitis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017 Oct 4;2(4):pii: E52. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2040052. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2040052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nugent C, Berdine G, Nugent K. The undead in culture and science. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2018;31:244–9. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2018.1441216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awasthi M, Parmar H, Patankar T, Castillo M. Imaging findings in rabies encephalitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:677–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2018 Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool . Last accessed, January 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont JR, Earle KM. Human rabies encephalitis. A study of forty-nine fatal cases with a review of the literature. Neurology. 1965;15:1023–34. doi: 10.1212/wnl.15.11.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hueffer K, Khatri S, Rideout S, Harris MB, Papke RL, Stokes C, Schulte MK. Rabies virus modifies host behaviour through a snake-toxin like region of its glycoprotein that inhibits neurotransmitter receptors in the CNS. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12818. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verran J, Reyes XA. Emerging Infectious Literatures and the Zombie. Condition. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1774–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littlewood R, Douyon C. Clinical findings in three cases of zombification. Lancet. 1997;350:1094–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams AJ, Banister SD, Irizarry L, Trecki J, Schwartz M, Gerona R. “Zombie” Outbreak Caused by the Synthetic Cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zombie Preparedness. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/zombie/index.htm . Last accessed, January 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Headquarters United States Strategic Command. Counter-Zombie Dominance. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170328232114/http://www.cubadebate.cu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/CONPLAN-8888.pdf . Last accessed, January 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sartin JS. Contagious Horror: Infectious Themes in Fiction and Film. Clin Med Res. 2019;17:41–46. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2019.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahadevan A, Suja MS, Mani RS, Shankar SK. Perspectives in Diagnosis and Treatment of Rabies Viral Encephalitis: Insights from Pathogenesis. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13:477–92. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothe K, Tsokos M, Handrick W. Animal and Human Bite Wounds. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:433–42. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manning SE, Rupprecht CE, Fishbein D, Hanlon CA, Lumlertdacha B, Guerra M, Meltzer MI, Dhankhar P, Vaidya SA, Jenkins SR, Sun B, Hull HF. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human rabies prevention--United States, 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Ma J, Nie J, Li J, Cao S, Wang L, Yu C, Huang W, Li Y, Yu Y, Liang M, Zirkle B, Chen XS, Li X, Kong W, Wang Y. Antigenic variations of recent street rabies virus. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8:1584–1592. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1683436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faber M, Faber ML, Papaneri A, Bette M, Weihe E, Dietzschold B, Schnell MJ. A single amino acid change in rabies virus glycoprotein increases virus spread and enhances virus pathogenicity. J Virol. 2005;79:14141–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14141-14148.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Aken J, Hammond E. Genetic engineering and biological weapons. New technologies, desires and threats from biological research. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(Spec No:S57):60. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Severe Acute Respiratory Sindrome (SARS): a new and intriguing diagnostic challenge. Biochim Clin. 2003;27:177–85. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulton F. Which bio-weapons might be used by terrorists against the United Kingdom? Med Confl Surviv. 2003;19:326–30. doi: 10.1080/13623690308409706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher CR, Streicker DG, Schnell MJ. The spread and evolution of rabies virus: conquering new frontiers. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:241–255. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Than K. “Zombie Virus” Possible via Rabies-Flu Hybrid? National Geographic. 2010 Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/10/1001027-rabies-influenza-zombie-virus-science/ : Last accessed, January 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koch C, Crick F. The zombie within. Nature. 2001;411:893. doi: 10.1038/35082161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alemi AA, Bierbaum M, Myers CR, Sethna JP. You can run, you can hide: The epidemiology and statistical mechanics of zombies. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2015;92:052801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.052801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warrell MJ. Developments in human rabies prophylaxis. Rev Sci Tech. 2018;37:629–647. doi: 10.20506/rst.37.2.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher CR, Schnell MJ. New developments in rabies vaccination. Rev Sci Tech. 2018;37:657–672. doi: 10.20506/rst.37.2.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]