Abstract

SUMMARY: We present a patient with a new intracranial mass lesion that was initially interpreted as a metastasis on conventional anatomic MR imaging. On dynamic, contrast-enhanced, susceptibility-weighted perfusion MR imaging, however, there were regional hemodynamic differences within the lesion. Image-guided open biopsy targeting these regions uncovered a collision tumor between a typical meningioma and a metastatic breast carcinoma. In cases where conventional anatomic MR imaging is ambiguous, physiology-based neuroimaging methods provide complementary physiologic information useful for discriminating between histologically unique tissue types.

The ability to discriminate between histologically unique tissue types remains a significant challenge for neuroradiologists. Although conventional anatomic MR imaging provides excellent soft-tissue resolution, many intracranial pathologies share similar MR features, making a definitive diagnosis difficult.1 To overcome this lack of specificity, physiology-based neuroimaging methods have emerged that reflect the in vivo physiologic parameters, which may allow for better differentiation.

Intracranial collision tumors provide a rare opportunity to demonstrate the complementary role of anatomic and physiologic MR imaging, because these lesions involve the juxtaposition of 2 unique tumor types within a single mass lesion. On conventional MR imaging, collision tumors are often misinterpreted for metastases or primary neoplasms.2–5 By using physiology-based neuroimaging methods, it may be possible to differentiate each tumor type by their distinct biologic properties. In this report, we present the dynamic, contrast-enhanced, susceptibility-weighted perfusion MR imaging (pMRI) findings for an intracranial collision tumor between a typical meningioma and a metastatic breast carcinoma.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a 2-week history of worsening headaches with intermittent episodes of nausea and vomiting. Her medical history was significant for a breast carcinoma treated by lumpectomy and radiation therapy 10 years earlier. A year before her current admission, the patient developed recurrence in her mediastinum that was treated by chemotherapy for presumed breast carcinoma metastasis. There was no other history of malignancy or metastasis to the brain documented.

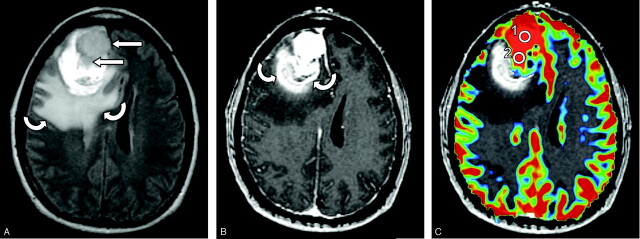

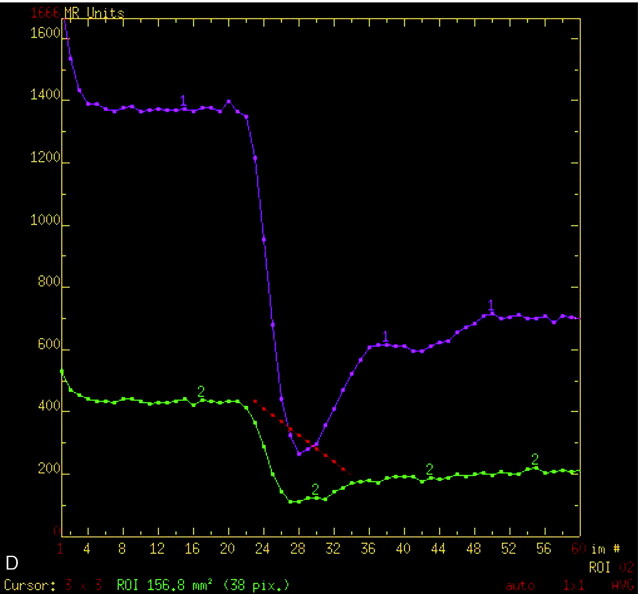

On conventional MR imaging, a right frontal bilobed mass was seen intimately related to the adjacent paramedian and anterior frontal dura with moderate amounts of surrounding edema (Fig 1A). An area of T1 shortening was noted in the posterior rim that was suggestive for blood products. On postcontrast spoiled gradient-recalled (SPGR) T1-weighted images (Fig 1B), the lesion demonstrated uniform contrast enhancement. Perfusion MR color maps were overlaid on to the corresponding postcontrast images (Fig 1C) and showed increased relative cerebral blood volumes (rCBVs) within the enhancing lesion. Two regions of interest, each measuring 5 mm in diameter, were defined on the anterior and posterior lobes of the lesion (Fig 1C) and the T2* susceptibility signal intensity-time curves were determined (Fig 1D). The anterior region of interest showed a greater maximum signal intensity drop and greater signal intensity recovery compared with the posterior region of interest, which suggests that the anterior component was more vascular and less permeable than the posterior component of the mass, respectively.

Fig 1.

Images of a 56-year-old woman with a history of breast carcinoma presenting with 2 weeks of headache, nausea, and vomiting. Image-guided open biopsy demonstrated a collision tumor between a typical meningioma and metastatic breast carcinoma.

A, Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (10,000/148/2,200 milliseconds [TR/TE/TI]) image. A heterogeneously intense, right anterior frontal bilobed mass (straight arrows) is seen with surrounding edema and hemorrhage (curved arrows).

B, Axial postcontrast spoiled gradient-recalled (SPGR; 34/8) T1-weighted image. The mass demonstrates uniform contrast enhancement with a posterior rim of hemorrhage (curved arrows).

C, Perfusion MR color map overlaid onto the corresponding axial postcontrast section. Relative cerebral blood volume is increased within the bilobed enhancing lesion. Two regions of interest, labeled 1 and 2, are defined on the anterior and posterior lobes of the tumor.

D, T2* susceptibility signal intensity-time curves. The anterior (1) and posterior (2) lobes demonstrate differences in the degree of signal intensity drop and pattern of signal intensity recovery.

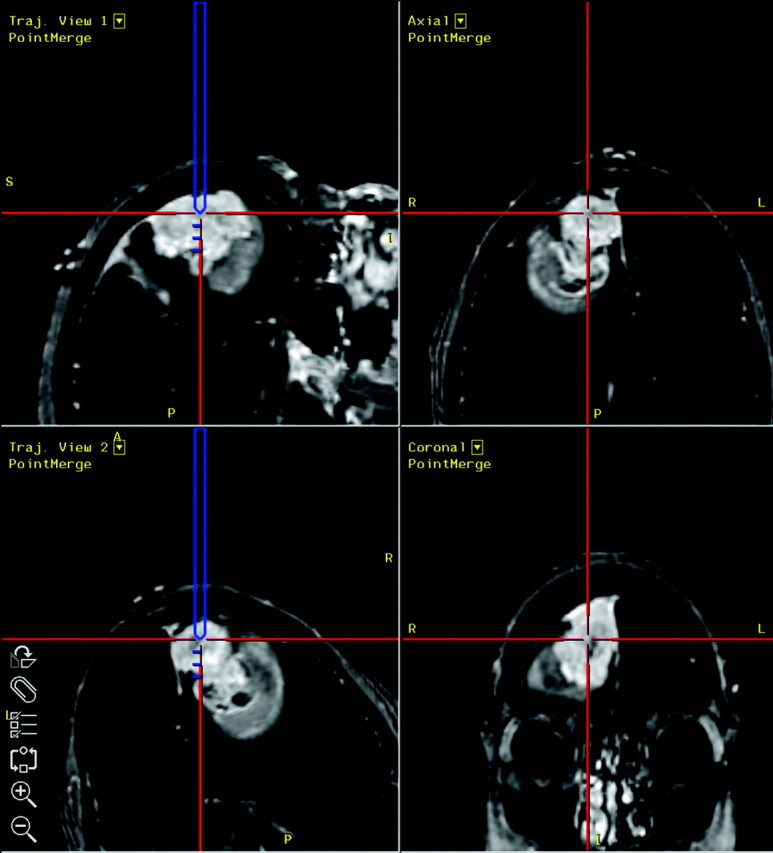

Before volumetric resection, an open biopsy targeting tissue corresponding to the anterior and posterior regions of interest (Fig 2) was performed with image guidance by using the StealthStation neuronavigation system (MedTronic SNT, Louisville, Colo). Following this, gross total resection was achieved with no complications and the patient recovered without incident.

Fig 2.

Intraoperative screen captures from the StealthStation neuronavigation system. The anterior lobe, corresponding to region of interest 1, is targeted for image-guided open biopsy.

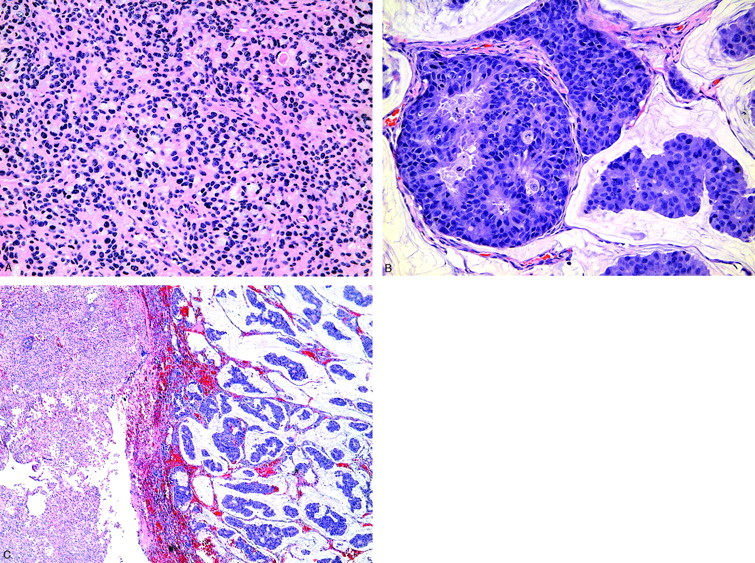

Histopathologic examination of the anterior biopsy was consistent for a typical meningioma (World Health Organization grade 1) composed of a monotonous population of meningothelial cells (Fig 3A). The posterior biopsy comprised pleomorphic tumor cells arranged in attenuated clusters floating in pools of extracellular mucin (Fig 3B) that were histologically identical to the patient’s prior breast carcinoma. Further sectioning revealed the interface between the 2 tumors, confirming the diagnosis of a collision tumor between a typical meningioma and a metastatic breast carcinoma (Fig 3C).

Fig 3.

Histopathologic sections from the anterior and posterior lobes corresponding to regions of interest 1 and 2, respectively.

A, Anterior biopsy shows hyperchromatic tumor cells arranged in sheets consistent for a typical meningioma (hematoxylin-eosin, magnification ×200).

B, Posterior biopsy demonstrates pleomorphic tumor cells arranged in attenuated clusters with pseudoglandular formation. This is histologically identical to the patient’s prior breast carcinoma (hematoxylin-eosin, magnification ×200).

C, Section through the resected tumor reveals the interface between the typical meningioma and metastatic breast carcinoma (hematoxylin-eosin, magnification ×40).

Discussion

Conventional anatomic MR imaging is nonspecific for discriminating between unique tissue types. On the basis of our patient’s conventional MR findings, we initially interpreted her intracranial collision tumor as a metastasis from her primary breast carcinoma. Although the mass was clearly bilobed, which suggests the presence of 2 discrete components, the conventional MR features and the contrast enhancement patterns were indistinguishable. According to findings from other studies,6,7 meningiomas and durally based metastases are often confused for one another on conventional MR images. Thus, it is not surprising that nearly all intracranial collision tumors have eluded preoperative radiologic diagnosis and were only discovered incidentally during postoperative pathologic examination.4,5,8

pMRI relies on hemodynamic differences in microvasculature to discriminate between unique tissue types. On the T2* susceptibility signal intensity-time curve, tissues with greater microvascular attenuation show larger T2* signal intensity drops, while capillaries with greater permeability show incomplete T2* signal intensity recovery.9,10 In our patient’s mass, the anterior and posterior lobes had markedly different T2* susceptibility signal intensity-time curves (Fig 1D), which suggests that there were intrinsic differences in the microvascular attenuation and capillary permeability for each. This raised the possibility of 2 unique tissue types, which was confirmed by image-guided open biopsy that revealed a typical meningioma and a breast carcinoma metastasis.

The hemodynamic differences between typical meningiomas and breast carcinoma metastases may be explained by their known histologic differences in tumor microvasculature. Meningiomas are highly vascular tumors with densely packed capillaries,11 whereas breast carcinoma metastases have more diffusely spaced capillaries because of the interspersed pools of mucin.12 This difference in capillary attenuation is consistent with our pMRI findings, which showed a greater T2* maximal signal intensity drop, and therefore a greater rCBV, for the meningioma than the metastasis. Similarly, Kremer et al7 found that the mean rCBV of 16 meningiomas was significantly greater than that of 2 breast carcinoma metastases, thereby further confirming our findings.

Although meningiomas and metastases are both extra-axial tumors and thus lack a blood-brain barrier, our patient’s meningioma and breast cancer metastasis had profoundly different T2* susceptibility signal intensity recovery patterns suggesting differences in their tumor capillary permeability. According to Uematsu et al,13 this may be explained by examining the gap junctions, which function as the dominant route to the extravascular space. The gap junctions in meningiomas are often tortuous and elongated, and they are frequently covered by endothelial cells.11 Conversely, the gap junctions in breast carcinoma metastases are simple and straight, and they are freely open.14 These differences in gap junction structure may partly explain why we observed a complete lack of T2* signal intensity return to baseline, which is indicative of a greater degree of contrast leakage, in the breast carcinoma metastasis over the meningioma.

In summary, we demonstrated how pMRI could identify regions of hemodynamic differences between 2 unique tissue types that were not apparent on conventional anatomic MR imaging. Noninvasive characterization of tumor biology carries obvious implications in the management of brain tumor patients both before and after therapy. Recognizing tumor type and grade or differentiating recurrent tumor from therapy-related necrosis can significantly alter a patient’s clinical management.15,16 Our case report suggests that pMRI can be used to depict different areas of tissue microvasculature and thus shows promise in noninvasive quantitation and characterization of intracranial pathologies.

Before pMRI is incorporated into standard patient care, however, more rigorous and systematic validation is necessary by correlating pMRI-derived physiologic data with histopathology and outcome. Because most brain tumors demonstrate spatial heterogeneity with regional biologic variability, direct correlation between imaging findings and histopathologic results is required to establish physiologic-based MR imaging as a surrogate for in vivo tumor biology.

References

- 1.Cha S, Knopp EA, Johnson G, et al. Intracranial mass lesions: dynamic contrast-enhanced susceptibility-weighted echo-planar perfusion MR imaging. Radiology 2002;223:11–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DG, Paek SH, Chi JG, et al. Mixed tumour of schwannoma and meningioma components in a patient with NF-2. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139:1061–64; discussion 1064–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Szczesniak DM, et al. Combined oligodendroglioma/pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: a probable collision tumor: case report. Neurosurgery 2001;48:1358–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe T, Fujisawa H, Hasegawa M, et al. Metastasis of breast cancer to intracranial meningioma: case report. Am J Clin Oncol 2002;25:414–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baratelli GM, Ciccaglioni B, Dainese E, et al. Metastasis of breast carcinoma to intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg Sci 2004;48:71–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagle P, Villanueva P, Torrealba G, et al. Intracranial metastasis or meningioma? An uncommon clinical diagnostic dilemma. Surg Neurol 2002;58:241–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremer S, Grand S, Remy C, et al. Contribution of dynamic contrast MR imaging to the differentiation between dural metastasis and meningioma. Neuroradiology 2004;46:642–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A, Wallace C, Rewcastle B, et al. Metastases to meningioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:1120–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cha S, Lu S, Johnson G, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast MR imaging: correlation of signal intensity changes with cerebral blood volume measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging 2000;11:114–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law M, Kazmi K, Wetzel S, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion and conventional MR imaging findings for adult patients with cerebral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:997–1005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long DM. Vascular ultrastructure in human meningiomas and schwannomas. J Neurosurg 1973;38:409–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidi AJ, Fischer L, Harris JR, et al. Microvessel density and distribution in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86:614–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uematsu H, Maeda M, Sadato N, et al. Vascular permeability: quantitative measurement with double-echo dynamic MR imaging–theory and clinical application. Radiology 2000;214:912–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long DM. Capillary ultrastructure in human metastatic brain tumors. J Neurosurg 1979;51:53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Martinez AJ. Unreliability of contemporary neurodiagnostic imaging in evaluating suspected adult supratentorial (low-grade) astrocytoma. J Neurosurg 1993;79:533–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ricci PE, Karis JP, Heiserman JE, et al. Differentiating recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis: time for re-evaluation of positron emission tomography? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:407–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]