Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: On the basis of limited available data, brain MR imaging abnormalities in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) have been predominantly attributed to calcineurin inhibitors (CIs), characteristically presenting as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

The goal of this study was to evaluate whether CIs play an important role in the incidence, nature, and location of MR imaging brain lesions in adult KTRs by comparing them with dialysis-dependent patients.

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed 98 brain MR imaging examinations in 77 consecutive KTRs presenting with neurologic symptoms from 1990 to 2003. The data were separated into 3 groups according to duration after transplantation of MR imaging: group 1, 0–3 months; group 2, 3–12 months; and group 3, >12 months. Twenty-six MR imaging examinations from 24 additional dialysis-dependent adults were used as controls and comprised group 0.

RESULTS: Acute changes (infarcts, infections, PRES) comprised 24% and 19% of lesions in KTRs and group 0 patients, respectively, with infarcts being the most common in all groups. Chronic lesions were responsible for 76% of changes in KTR and 81% in group 0 and were predominantly vascular in etiology. No statistically significant differences in incidence of PRES or other acute changes were found between dialysis-dependent patients and either individual KTR groups or all KTR patients combined. The deep gray matter lesions were more common in KTR, whereas frontal white matter was more frequently affected in patients on dialysis.

CONCLUSION: Our study does not support suggestion that MR imaging brain abnormalities in KTR are predominantly due to direct CI toxicity.

Kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) may present with various neurologic symptoms that require imaging studies of the central nervous system (CNS; 1–3). CNS lesions in KTRs have multiple etiologies, including cerebrovascular disease, which accounts for most cases (1–4). CNS infections and malignancies—particularly lymphoma—are also common in transplant recipients and may present with atypical clinical signs and symptoms (1–3, 5–11).

Calcineurin inhibitors (CIs) cyclosporine and tacrolimus (FK-506) are immunosuppressive agents used to control transplant rejection and graft-versus-host disease, and they have been linked with CNS toxicity of unclear etiology (12–14). Patients may experience a variety of symptoms, ranging from headache, mild tremor, paresthesias, and sleep disturbances to acute confusional state, lethargy, dysarthria, cortical blindness, seizures, and coma (1, 2, 12–16). In general, CNS symptoms induced by these drugs occur early after transplantation (12–17) and may or may not correlate with blood levels of these drugs (1, 2, 12, 18, 19). Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is considered the characteristic imaging presentation of CI neurotoxicity with subcortical and deep white matter changes consistent with vasogenic edema found predominantly in parietal and occipital lobes (16–21). The effects of CI on MR imaging abnormalities have been reported in small uncontrolled series and isolated case reports (15–28). It is not clear to what extent the described abnormalities are a unique consequence of CI treatment.

The purpose of this study was to establish the incidence, nature, and location of brain lesions in symptomatic KTRs by using MR imaging and to distinguish acute from chronic processes. MR imaging findings in KTRs treated with CIs were compared with those in dialysis-dependent patients before kidney transplant who presented with similar CNS symptoms to establish possible effects of CI treatment on development of brain lesions, in particular PRES.

Methods

Between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2003, a total of 868 patients received kidney transplants at the Medical University of South Carolina, either alone or in combination with pancreas, liver, and heart transplantation. One hundred nineteen patients who received simultaneous kidney/liver, kidney/heart and kidney/pancreas transplants were not included in the study. The medical records of the remaining 749 recipients were reviewed, and 77 consecutive patients who presented with neurologic symptoms that required further MR imaging evaluation were identified. All were adults, ranging in age from 18 to 72 years (mean, 47 years). The study also included 26 MR imaging examinations performed in 24 dialysis-dependent patients with CNS symptoms who had brain MR imaging before kidney transplant. These patients were similar to those receiving post-transplant MR imaging in terms of age, sex, and ethnic background and served as a comparison group (group 0).

All MR imaging examinations were evaluated retrospectively by 2 neuroradiologists. Each neuroradiologist independently reviewed the MR images of every patient and recorded all abnormalities on a standardized form that categorized and quantified the radiographic findings. If the interpretations between radiologists differed, consensus was achieved through discussion. The neuroradiologists were aware that the images were obtained from either KTRs or dialysis-dependent patients, but they were completely unaware whether and when kidney transplantation was performed.

MR imaging data on 77 KTRs were separated into 3 groups, on the basis of the duration between transplantation and initial MR imaging examination. Group 1 (19/77) consisted of patients who had MR imaging within 3 months of transplantation. Patients in group 2 (22/77) had MR imaging between 3 and 12 months after transplantation. Group 3 consisted of 36 of 77 patients who had MR imaging examination 1–6 years after transplantation (average, 30 months). Twenty-one, 26, and 51 MR imaging examinations were performed in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In group 1, follow-up MR imaging examinations were performed in 2 patients (each having 3 studies), in group 2 in 2 patients (4 studies with 2 studies each), and in group 3 in 8 patients (6 patients having 1 study each; 1 patient having 2 studies; 1 patient having 3 studies). Follow-up MR imaging studies were performed within the same timeframe as the initial study, so any new findings remained within the same patient group. Altogether, there were 98 MR imaging examinations in 77 KTRs and 26 studies in 24 comparison group 0 patients (one group 0 patient underwent 3 MR imaging studies).

The levels of serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium), and cyclosporine or tacrolimus were analyzed in all patients at the time of MR imaging examination. Serum cholesterol was available for 70 KTRs. None of the studied patients had advanced renal failure that could be implicated for CNS symptoms. Two-thirds of recipients were treated with cyclosporine and one-third with tacrolimus. At the time of MR imaging examination, cyclosporine and tacrolimus levels were within the desired therapeutic range in all patients.

A standard brain MR imaging protocol was used throughout the study and included sagittal T1-weighted images, T1-weighted and T2-weighted images in the axial plane, followed by postcontrast T1-weighted images in at least 2 planes in all patients. Axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images were acquired in 88 studies, and diffusion-weighted images (DWIs) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were obtained in 71 of 98 examinations in KTRs. FLAIR, DWI and ADC were performed in all patients from comparison group 0.

Locations of lesions within the brain were assessed. In addition, brain lesions were classified as acute or chronic on the basis of the imaging findings. Acute brain changes demonstrated on MR imaging implied acute and subacute infarction (including multiple embolic infarcts), infection, and PRES. Chronic infarction with encephalomalacia, scattered chronic white matter ischemic changes corresponding to microangiopathy, new neoplasms (presumably related to kidney transplantation), bony changes of the calvaria, and dural thickening were classified as chronic lesions.

Statistical differences between groups 0, 1, 2, and 3 were tested on a pairwise basis by using the 2-sided Fisher exact test for incidence of each of the following variables detected on MR imaging: acute infarct (AI), infection (I), PRES, lacunar infarct (LI), microangiopathy (MA), tumor (T), dural thickening (Dura), thickened heterogenous calvaria (C), and number of normal brains. In addition, groups 1, 2, and 3 were combined to form a single post-transplant group that was then compared with the control group for the same set of variables. The observed differences in location of brain lesions between the groups were also tested for statistical significance by using the 2-sided Fisher exact test for the following locations: frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, deep periventricular (DPV), and cerebellar white matter; thalamus, basal ganglia (BG), and cortical gray matter; and brain stem. In addition, statistical differences between the groups were also tested for incidence of the most common clinical presentations. This study was descriptive in design and as such the power to detect differences between groups was limited by the sample size available for analysis.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Medical University of South Carolina.

Results

Clinical Review

CNS symptoms requiring MR imaging evaluation occurred in 10.3% (77/749) of KTRs. The most common clinical symptoms in all groups are presented in (Table 1). Some patients presented with more than one symptom. In post-transplant patients altered mental status (AMS) was the most common presenting symptom (38% of patients) followed by headache (27%), infection (16%), and seizures (12%). These 4 symptoms accounted for 67% of CNS disturbances that required referral for MR imaging examinations. In comparison group 0, seizures and headache were the most common presenting symptoms. Seizures, AMS, headache, and infection combined accounted for 52% of symptoms in this group. Other rare clinical manifestations in all groups included paresthesia, hearing loss, hypogonadism, hyperprolactinemia, protracted unexplained nausea and vomiting, intracranial hypertension, and facial nerve palsy. The only statistically significant differences in clinical presentation between the control group 0 and KTRs were AMS, which was more common in group 1 (P = .003) and group 2 (P = .044), and infection, which was more frequent in group 2 (P = .043).

TABLE 1:

Most common clinical presentations in kidney transplant recipients

| Group 0(n = 24) | Group 1(n = 19) | Group 2(n = 22) | Group 3(n = 36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered mental status | (13) | 11 (58) | 9 (41) | 9 (25) |

| Headache | 4 (17) | 2 (11) | 4 (18) | 15 (42) |

| Seizures | 4 (17) | 6 (32) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Infection | 1 (4) | 2 (11) | 6 (27) | 4 (11) |

| Vision disturbance | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 4 (11) |

| Hemiparesis | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (8) |

| Weakness | 2 (8) | 2 (11) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Ataxia | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (9) | 1 (3) |

| Aphasia | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Syncope | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) |

Note.—Number of patients is followed by percentage in parentheses.

The onset of symptoms before the MR imaging ranged from 24 hours to 2 weeks and did not differ from group to group, including group 0. The levels of all tested electrolytes were within normal limits. Serum cholesterol was available in 70 KTRs with mean level of 207 mg/dL. Twelve (17%) and 6 (9%) patients had levels <150 mg/dL and 120 mg/dL, respectively. At the time of MR studies CI levels were within desired range in all KTRs (ie, trough cyclosporine levels [FPIA; Abbot, Chicago, IL] were kept between 300 and 450 ng/mL for the first 3 months post-transplantation between 200 and 350 ng/mL 3–6 months after transplantation, and between 100 and 150 ng/mL after 6 months). Trough tacrolimus levels (MEIA; Abbot) were between 10 and 20 ng/mL for the first 3 months and between 5 and 15 ng/mL after 3 months post-transplantation.

MR Imaging

Twenty-three of 98 MR imaging examinations (23%) performed on KTRs and 8 of 26 (31%) of examinations performed on patients in comparison group 0 were normal. We detected 27 lesions on 18 MR imaging examinations in comparison group 0 and 105 lesions on 75 MR imaging examinations in 54 KTRs (groups 1, 2, and 3). Incidental findings unrelated to the kidney transplantation were found in 5 patients. These included arachnoid cyst in a patient from group 0, choroid plexus cyst in a patient from group 2, and meningioma in 2 patients and a venous developmental anomaly in one patient in group 3.

Location of MR Imaging Lesions

Location of lesions detected by MR imaging is shown in (Table 2). Predominant location of lesions demonstrated on T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and FLAIR imaging was within white matter and comprised 60% of all lesions in KTRs (groups 1, 2, and 3) and 74% of all lesions in comparison group 0. DPV white matter area and frontal lobe were most commonly affected. Gray matter lesions were less common, accounting for 27% of all lesions in KTRs and 7% of all lesions in comparison group 0, with the BG being most commonly affected. There were 2 statistically significant differences: the deep gray matter lesions (BG and thalami) were more common in KTRs (P = .0434), whereas frontal white matter abnormalities were more frequently seen in patients on dialysis (P = .0191).

TABLE 2:

Location of lesions in 26 pre- and post-transplant MR imaging examinations

| Normal | White Matter |

Gray Matter |

Brain Stem | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | Parietal | Occipital | Temporal | DPV | Cerebellum | Basal Ganglia | Thalamus | Cortex | |||

| Pretransplant | 8 (31) | 9 (35) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 8 (31) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 4 (15) | 1 (4) |

| Post-transplant | 23 (23) | 13 (13) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 38 (39) | 4 (4) | 15 (15) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) | 5 (5) |

Note.—Number of patients with lesions is followed by percentage in parentheses. DPV indicates deep periventricular area.

Acute MR Imaging Changes

Acute brain abnormalities consisting of acute and subacute infarcts, infection, and PRES comprised 24% of MR imaging changes in KTRs (groups 1, 2, and 3) and 19% of MR imaging changes in comparison group 0 (Table 3).

TABLE 3:

Lesion type on MR image in patients before (group 0) and after kidney transplant (groups 1–3)

| Group(s)* | Normal | Acute Changes |

Chronic Changes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | I | PRES | LI | MA | T | Dura | C | ||

| 0 | 8 (33) | 2 (8) | 0 | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 10 (42) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 4 (21) | 3 (16) | 2 (11) | 1 (5) | 4 (21) | 6 (32) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| 2 | 7 (32) | 2 (9) | 0 | 1 (5) | 7 (32) | 10 (45) | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (9) |

| 3 | 12 (33) | 4 (11) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 6 (17) | 13 (33) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 3 (8) |

| 1–3 | 23 (30) | 9 (12) | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 17 (22) | 29 (38) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 6 (8) |

Note.—Number of patients is followed by percentage in parentheses. AI indicates acute and subacute infarct; I, infection; PRES, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; LI, chronic lacunar infarct; MA, microangiopathy; T, tumor; Dura, dural thickening; C, thickened calvaria.

Group 0 (no. patients/no. MR imaging examinations), 24/26; group 1, 19/21; group 2, 22/26; group 3, 36/51.

Acute infarcts were found in 12% of KTRs and 8% of the patients in comparison group 0. Of 6 KTRs with acute infarcts, the findings were consistent with multiple embolic lesions in 4 patients, all from group 3 (Fig 1). The remaining 2 cases were in group 1 and had acute middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction. Subacute infarcts were found in MCA distribution and BG in 3 cases; one was in group 1 and 2 were in group 2. Acute infarcts were found in 2 patients from comparison group 0. In one of them findings were indicative of cerebral vasculitis, and the other patient suffered cardiac arrest with bilateral watershed infarcts.

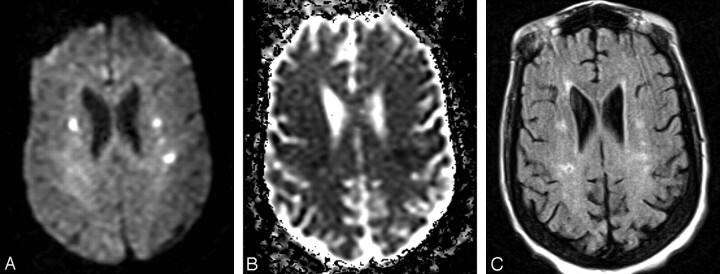

Fig 1.

A 52-year-old-man (group 3) with multiple acute embolic infarctions.

A, Axial DWI shows small bilateral hyperintense lesions indicative of embolic infarcts.

B, Axial ADC map reveals low signal intensity within the lesions, consistent with restricted diffusion of water molecules, confirming acute nature of embolic infarcts.

C, FLAIR image at approximately the same level as A and B demonstrates faint hyperintensity of the lesions.

MR imaging findings consistent with infection were found in 5 KTRs (6.5%). No infectious process was found in patients from comparison group 0. In one patient from group 1, aseptic viral meningitis was diagnosed. The other patient from group 1 who presented with ophthalmoplegia and cellulitis had mucormycosis and eventually died. In one patient from group 3, diagnosis of cryptoccocal meningitis was established. In the second case from group 3, multiple ring-enhancing lesions with restricted diffusion in the right BG and left temporoparietal region corresponded to fungal abscesses. (Fig 2). The third patient from group 3 had acute sinusitis with orbital cellulitis without intracranial spread of infection.

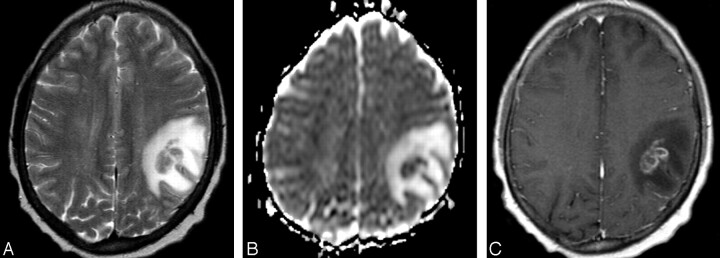

Fig 2.

A 48-year-old man (group 3) with cerebral fungal abscess.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows a relatively isointense intra-axial lesion with surrounding hyperintense vasogenic edema in the right frontoparietal region.

B, Corresponding axial ADC map shows lower signal intensity of the lesion compared with the normal-appearing brain parenchyma, consistent with relatively decreased diffusion, as typically seen within brain abscesses. The lesion is surrounded by increased diffusion of vasogenic edema.

C, Postcontrast axial T1-weighted image corresponding to A and B demonstrates irregular, predominantly peripheral enhancement of the mass.

PRES syndrome (Fig 3) with changes in the occipitoparietal region, frontal area, BG, or cerebellum was diagnosed in 4 (5%) of the KTRs and in one (4%) patient in comparison group 0, and all of them recovered fully. The levels of all tested electrolytes and serum cholesterol were within normal limits at the time of the MR examination in all patients with PRES.

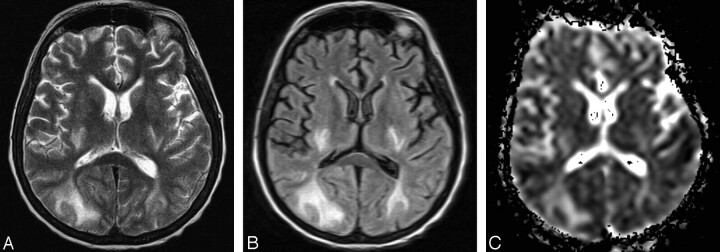

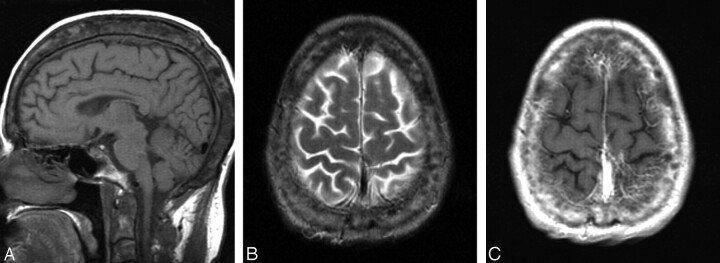

Fig 3.

A 45-year-old woman (group 2) with PRES.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows bilateral abnormal hyperintense signal intensity in the occipital subcortical white matter and in the posterior limb of the internal capsule.

B, Corresponding axial FLAIR image shows the hyperintense abnormalities more clearly.

C, On axial ADC map corresponding to A and B increased signal intensity of the abnormalities is seen, consistent with increased diffusion, which is indicative of vasogenic edema.

Chronic MR Imaging Changes

In all studied groups chronic changes were more common than acute: chronic lesions comprised 76% of MR imaging changes in KTRs and 81% of MR imaging changes in group 0 (Table 3).

The most common chronic lesions in both KTRs and comparison group 0, occurring in 36% and 42% of cases, respectively, were nonspecific scattered white matter ischemic changes corresponding to microangiopathy. Old lacunar infarcts comprised 13% of chronic changes in comparison group 0% and 22% in KTRs. In KTRs, lacunar infarcts were found within BG, pons, and cerebellum and were most frequent in group 2. Only one patient from comparison group 0 had lacunar infarct, which was located in the pons. Primary CNS lymphoma was found in the cerebellum of one group 3 patient, who is alive 2 years after the diagnosis was established (Fig 4).

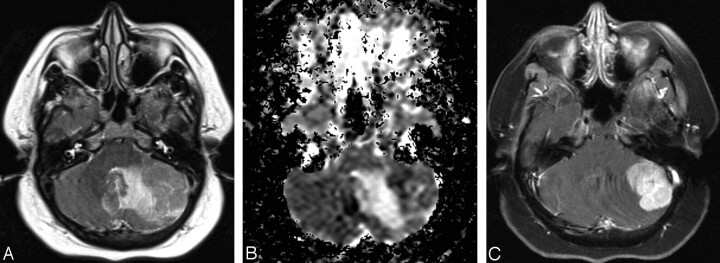

Fig 4.

A 39-year-old woman (group 3) with cerebellar lymphoma.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows an isointense left cerebellar mass surrounded by hyperintense area of vasogenic edema.

B, Axial ADC map corresponding to A reveals relatively decreased diffusion within the mass with surrounding increased diffusion of the vasogenic edema. Relatively low diffusion rate is indicative of high cellularity of the mass.

C, Postcontrast fat-suppressed axial T1-weighted corresponding to A and B images demonstrates attenuated homogenous enhancement of the mass.

Thickening of calvaria with widening of the diploic space and heterogenous T1 signal intensity was detected in 6 (8%) KTRs (Fig 5) and in none of group 0 patients. Dural thickening was associated with the changes of calvaria in 4 KTRs (5%). These patients had end-stage renal disease (ESRD) for a mean period of 8 years (range, 4–20 years). All of them had history of failed kidney transplant in the past, but at the time of MR imaging studies their transplanted kidneys were functioning well. Only one of the patients with changes of calvaria had hemoglobin of 9 g/dL, and the level was >11 g/dL in the others.

Fig 5.

A 31-year-old woman (group 1) with heterogenous calvarial thickening.

A, Midsagittal T1-weighted image demonstrates increased thickness of the calvaria with widening of the diploic space and abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity. This finding is presumably related to a long-standing chronic renal failure and associated chronic anemia and osteodistrophy before kidney transplantation.

B, Axial T2-weighted image shows thickened and heterogenous diploic space of the calvaria.

C, Axial postcontrast T1-weighted image corresponding to B reveals heterogenous enhancement of the calvaria.

Infections and tumors were found only in KTRs; however, pairwise differences for groups 0, 1, 2, and 3 were not statistically significant at the .05 level for any of the variables AI, I, PRES, LI, MA, T, Dura, C, or number of normal brains. The most notable difference was in incidence of infections (0% in group 0 and 11% in group 1) with a P value of .189. When the same set of variables was compared between the pretransplant group (0) and the combined post-transplant groups (1–3), differences were again not significant at the .05 level. The most prominent difference between the 2 groups was in heterogenous thickening of the calvaria (0% in pretransplant group and 8% in KTRs), with P = .331.

Discussion

Organ transplant recipients are at risk for a variety of CNS complications including cerebrovascular insults, infection, lymphoma, electrolyte disturbances, hypertensive encephalopathy, and toxicity induced by immunosuppressive agents (1–12). Brain MR imaging allows fine characterization and precise localization of lesions that occur in these patients. To the best of our knowledge, the current study represents the largest single-center evaluation of brain MR imaging abnormalities in KTRs. In addition, this is the only study that included a comparison group consisting of dialysis-dependent patients who underwent brain MR imaging examinations before their kidney transplant. We separated KTRs into 3 subgroups on the basis of the time interval between MR imaging examination and kidney transplant because exposure to CI and occurrence of certain complications varies in the post-transplant course (12, 13, 15, 18, 19). We were not able to detect statistically significant difference in MR imaging findings between pretransplant (comparison group 0) and post-transplant patients or among the 3 post-transplant groups, and our results point to several important findings.

In our series, CNS symptoms and signs that required MR imaging evaluation occurred in 10% of KTRs. This is in agreement with the previously published data, where CNS abnormalities occurred in 5% to 30% of KTRs (2, 5, 14). Major CNS complications attributed to CI include headache, confusion, AMS, seizure, lethargy, cortical blindness, auditory and visual hallucinations, spasticity, paresis, ataxia, and coma (12–17). We found AMS, headache, and seizures to be the most common symptoms in KTRs, but also in pretransplant patients. At the time of MR imaging examination, none of the KTRs had hypertensive encephalopathy, altered serum electrolyte and glucose levels, or advanced renal failure. As expected, referral for MR imaging for possible CNS infection was more common in KTRs than in pretransplant patients. Among KTRs, seizures and AMS had a tendency to develop early, within the first 3 months after transplantation, similar to previous reports (2, 12–17). AMS was significantly more common in the first 3 months after transplant compared with dialysis-dependent patients, which may be due to CI neurotoxicity. The CIs were within desired range at the time of MR imaging, though it has been shown that CI-related neurotoxicity occurs even at therapeutic level, which may, at least in part, be due to imperfections of CI-level measurement (18, 19) and individual sensitivity and metabolism of CIs.

In all studied patients, white matter was more commonly affected than gray matter, particularly within periventricular and frontal lobe, as reported elsewhere (18–23, 29–31). Most MR imaging findings in the present study included acute and chronic vascular changes affecting both large and small blood vessels.

Furukawa et al (20) could not find differences in MR imaging abnormalities between patients treated with cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and we decided to combine findings in patients receiving either of the CI inhibitors. The pathogenesis of CI-induced CNS toxicity remains uncertain. It is still unresolved whether the clinical symptoms and changes detected by MR imaging in post-transplant patients treated with CIs are due to the direct drug toxicity, hypomagnesemia, hypocholesterolemia, hypertension, or the combination of these factors (12, 14, 16, 17, 21). In our series, none of the patients had hypomagnesemia or arterial hypertension at the time of clinical symptoms and MR imaging examination, and only 9% of patients had a cholesterol level <120 mg/dL. This probably contributed to the low incidence of CI CNS toxicity in our study.

Most brain MR imaging abnormalities in transplant recipients, including KTRs, have been attributed to CI treatment and are predominantly based on isolated case reports and short, uncontrolled series (15–31). PRES has been considered a common and typical consequence of CI neurotoxicity, for which the term immunosuppressive-associated leukoencephalopathy has also been frequently used. PRES is typically characterized by headache, AMS, seizures, and visual loss associated with imaging findings of bilateral subcortical and cortical edema with a predominantly posterior distribution. On ADC maps vasogenic edema seen in PRES can easily be distinguished from cytoxic edema in irreversible ischemic injury (20, 29, 32). Watershed areas of the brain appear to be most vulnerable to such insult (30, 31). CI-induced neurotoxicity may lead to alteration of the blood-brain barrier with increase in microvascular permeability and vasogenic edema in the white matter or cortex. It has also been suggested that direct capillary endothelial cell injury caused by release of potent vasoconstrictors such as endothelin or thromboxane results in vasospasm and that thrombotic microangiopathy may be responsible for microvascular damage (14, 30–32). PRES can be seen in conditions such as eclampsia, hypertensive encephalopathy, systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombotic microangiopathy, and with other medications, in addition to CI toxicity.

Fifty cases of CI-associated PRES in transplant recipients reported in the literature were recently reviewed (12). This review has shown that most of reported cases occurred following liver transplantation (31 or 62%), with only 8 cases in KTRs (12). Because kidney transplantation has been relatively commonly performed, these findings indicate that PRES may be a comparatively rare event in KTRs. This assumption is also indirectly supported by a recent prospective study that evaluated MR imaging findings in organ transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus who developed neurologic complication (19). Neurologic complications occurred in 6.8% of 206 patients, of whom 13 had undergone orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) and one had received a small bowel transplant. MR imaging studies showed abnormal findings in 6 of 14 cases, and PRES was the etiology in 5. OLT recipients therefore appear to be at significantly increased risk, and an overall 26% incidence of neurologic complications in liver transplant recipients has been documented (33). PRES is also relatively frequent in allogenic bone marrow transplantation; it was recently found in 7.2% percent of patients (32). The review by Singh et al also revealed that PRES tends to occur early in transplant recipients: 82% of the cases occurred within the first 3 months (12).

In our study, we found PRES in 5% of KTRs, but also in 4% in the comparison group 0, and there was no statistical significance in incidence between the groups. Also, there was very similar incidence of PRES at different times after transplant, which is different from reported data for all organ transplant recipients, where PRES was much more common within the first 3 months. In fact, there was no difference observed among different KTR groups for any lesion type, despite tapering of CI levels with time. Although the statistical power is restricted by the number of patients in our study, our data suggest that PRES and other brain lesions are relatively uncommon in KTRs and that they may not be caused exclusively by CI neurotoxicity. It appears that risk of PRES in KTRs may be similar to dialysis-dependent patients and relatively low compared with other transplant recipients. The notion that differences in incidence of PRES may depend on transplanted organ type may be helpful in attempts to elucidate this leukoencephalopathy.

Chronic changes were more common than acute being predominantly vascular in etiology. Despite adequate kidney function and correction or amelioration of many uremic abnormalities KTRs continue to have significant atherosclerotic vascular disease within the CNS. Immunosuppressive agents and CI in particular play a major pathogenic role either by causing direct endothelial injury or indirectly through worsening hypertension, glucose intolerance, or dyslipidemia. This might explain significantly more common involvement of deep gray matter lesion (BG) in KTRs compared with patients on dialysis. Treatment with tacrolimus has been also associated with the development of cortical laminar necrosis due to profound hypoxia (34) and PRES may in some cases at least in part result in areas of infarction, but these changes were completely reversible in all of our patients.

We found CNS infections in 6% of KTRs, a rate that is similar to previous reports (1–3, 5, 6). We did not find any case of progressive multifocal encephalopathy in our study group. CNS lymphoma was found in one KTR, representing a prevalence of 3% in our series. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders occur in 0.9% of KTRs (8–10). The most common CNS location of post-transplant lymphomas is in BG (40%), followed by the frontal lobe (25%) (9). Lymphomas occur in the cerebellum in 9% of cases and have somewhat different imaging features compared with primary CNS lymphoma (9). It is somewhat surprising that, in our study, there were no statistically significant differences between KTRs and dialysis-dependent patients in incidence of infections and tumors.

Previously unreported findings in our study are changes involving calvaria and dura. The significance and the nature of these uncommon lesions remain unclear. KTRs with these changes had mild degrees of anemia, though hemoglobin levels were not different from those in patients from group 0; thus, chronic anemia is an unlikely cause for heterogeneously thickened calvaria. It is interesting that these changes were found in patients with long histories of ESRD and previous kidney transplants. Absence of such lesions in patients with ESRD before transplant argues against their relationship to uremic osteodystrophy. It is conceivable, however, that the KTRs on average had a longer history of ESRD compared with pretransplant patients and therefore possibly a higher chance of developing osteodystrophy, which may not be completely reversible. Another potential explanation is that these changes may perhaps also be associated with CI effects.

The main limitation of the study is its retrospective and descriptive design, where the power to detect differences between groups is limited by the sample size available for analysis. This may explain the observed lack of statistical significance in the incidence of infections, tumors, and calvarial changes between KTR and dialysis-dependent patients, although the difference between the groups appears striking and seems to indicate higher incidence in KTRs, which would be expected, at least for infections and tumors.

Conclusion

In KTRs the most common abnormalities in our study were white matter changes of vascular origin in keeping with the high prevalence of cerebrovascular abnormalities in this group of patients. Our major finding is that the prevalence of PRES and both acute and chronic changes do not differ significantly in pre- and post-transplant kidney recipients. Furthermore, we could not find a significant difference in the prevalence of brain abnormalities in early compared with late post-transplant periods when exposure to CI is tapered. Therefore, our study does not support the previous reports that those changes are mostly due to CI toxicity.

References

- 1.Donaghy M. Neurological complications. In: Morris PJ, ed. Kidney transplant. Philadelphia: Saunders;2001. :533–540

- 2.Snanoudj R, Kriaa F, Arzouk N, et al. Single center experience with cyclosporine therapy for kidney transplantation: analysis of a twenty-year period in 1200 patients. Transplant Proc 2004;36:183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaghy M. Neurologic considerations of organ transplantation. In: Ginnus LC, Cosimi AB, Morrris PJ, eds. Transplantation. Malden, MA: Blackwell;1999. :696–707

- 4.Adams HP, Dawson G, Coffman TJ, Corry JR. Stroke in renal transplant recipients. Arch Neurol 1986;43:113–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta SK, Manjunath-Prasad KS, Sharma BS, et al. Brain abscess in renal transplant recipients: report of three cases. Surg Neurol 1997;48:284–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin JH, Lee HK. Nocardial brain abscess in a renal transplant recipient. Clin Imaging 2003;27:321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renoult E, Georges E, Biava MF, et al. Toxoplasmosis in kidney transplant recipients: report of six cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snanoudj R, Durrbach A, Leblond V, et al. Primary brain lymphomas after kidney transplantation: presentation and outcome. Transplantation 2003;76:930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanh GP, O’Neill BP, Kurtin PJ. Posttransplant primary CNS lymphoma. Neurooncol 2000;2:229–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller WT, Siegel SG, Montone KT. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder: changing manifestations of disease in a renal transplant population. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1997;38:569–585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaphan E, Eusebio A, Witjas T, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the cavernous sinus associated with Epstein-Barr virus in kidney graft. Rev Neurol 2003;159:1055–1059 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh N, Bonham A, Fukui M. Immunosuppressive-associated leukoencephalopathy in organ transplant recipients. Transplantation 2000;69:467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Escrig M, Martinez J, Fernandez-Ponsati J, et al. Severe central nervous system toxicity after chronic treatment with cyclosporine. Clin Neuropharmacol 1994;17:298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wijdicks EFM. Neurotoxicity of immunosuppressive drugs. Liver Transpl 2001;7:937–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiemeneij IM, de Leeuw FE, Ramos LM, van Gijn. Acute headache as a presenting symptom of tacrolimus encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1126–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drachman BM, DeNofrio D, Acker MA, et al. Cortical blindness secondary to cyclosporine after orthotopic heart transplantation: a case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant 1996;15:1158–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzino G, Cloft H, Hemstreet MK, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy following organ transplantation: description of two cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1997;99:222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appignani BA, Bhadelia RA, Blacklow SC, et al. Neuroimaging findings in patients on immunosuppressive therapy: experience with tacrolimus toxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:683–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimono T, Miki Y, Toyoda H, et al. MR imaging with quantitative diffusion mapping of tacrolimus-induced neurotoxicity in organ transplant patients. Eur Radiol 2003;13:986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furukawa M, Terae S, Chu BC, et al. MRI in seven cases of tacrolimus (FK-506) encephalopathy: utility of FLAIR and diffusion-weighted imaging. Neuroradiology 2001;43:615–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarosz JM, Howlett DC, Cox TCS, Bingham JB. Cyclosporine-related reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy: MRI. Neuroradiology 1997;39:711–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz RB, Bravo SM, Klufas RA, et al. Cyclosporine neurotoxicity and its relationship to hypertensive encephalopathy: CT and MR findings in 16 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:627–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casey SO, Sampaio RC, Michel E, Truwit CL. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: utility of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR imaging in the detection of cortical and subcortical lesions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1199–1206 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheinman SJ, Reinitz ER, Petro G, et al. Cyclosporine central neurotoxicity following renal transplantation: report of a case using magnetic resonance images. Transplantation 1990;49:215–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedeoglu O, Springate JE, Najdzionek JS, Feld LG. Hypertensive encephalopathy and reversible magnetic resonance imaging changes in a renal transplant patient. Pediatr Nephrol 1996;10:769–771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeruss J, Braun SV, Reese JC, Guillot A. Cyclosporine-induced white and gray matter central nervous system lesions in a pediatric renal transplant patient. Pediatr Transplant 1998;2:45–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parvex P, Pinsk M, Bell LE, et al. Reversible encephalopathy associated with tacrolimus in pediatric renal transplants. Pediatr Nephrol 2001;16:537–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okoshi Y, Itoh M, Okimoto Y, et al. A case of FK 506-induced leukoencephalopathy. No To Shinkei 2002;54:51–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debaere C, Stadnik T, De Maeseneer M, Osteaux M. Diffusion-weighted MRI in cyclosporine A neurotoxicity for the classification of cerebral edema. Eur Radiol 1999;9:1916–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartinsky WS, Grabb BC, Zeigler Z, et al. Watershed imaging features and clinical vascular injury in cyclosporin A neurotoxicity. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1997;21:872–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartynski WS, Zeigler Z, Spearman MP, et al. Etiology of cortical and white matter lesions in cyclosporin-A and FK-506 neurotoxicity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1901–1914 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartynski WS, Zeigler ZR, Shadduck RK, Lister J. Pretransplantation conditioning influence on the occurrence of cyclosporine or FK-506 neurotoxicity in allogenic bone marrow transplantation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:261–269 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis MB, Howdle PD. Neurologic complications of liver transplantation in adults. Neurology 2003;61:1174–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bargallo N, Burrel M, Berenguer J, et al. Cortical laminar necrosis caused by immunosuppressive therapy and chemotherapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:479–284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]