Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Reported treatments and outcomes in aneurysmal carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs) have been admixed with those of cases considered to be symptomatic of intracavernous aneurysm. However, aneurysmal CCFs have clinical features distinct from those of dural arteriovenous fistulas, and treatment strategies similar to those of traumatic CCF are required. We evaluated our experience in placing detachable balloons in the management of spontaneous CCFs due to rupture of an intracavernous aneurysm.

METHODS: Six patients (one man, five women; mean age, 64.7 years) were treated for spontaneous direct CCF at our institution between 1995 and 2001. All patients presented with sudden ocular symptoms including exophthalmos, conjunctival injection, chemosis, and ocular motor palsies. Detachable latex balloons were used as the embolic material in five patients, and in one patient the cavernous sinus was packed transarterially with coils.

RESULTS: All six patients were successfully treated by means of transarterial embolization, and symptoms improved within a week.

CONCLUSION: Although other techniques using a transvenous approach and/or detachable coils may also be useful, embolization with detachable balloons should be a safe and effective method to immediately occlude the fistula.

Direct carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs) are included among type A fistulas according to Barrow’s classification (1). Etiologically, most direct CCFs are traumatic, but less commonly they may be spontaneous. Although spontaneous direct CCFs occasionally are associated with systemic connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (2–4), more cases are caused by rupture of an intracavernous carotid aneurysm. The latter type of CCF most often develops in middle-aged women (5–7). Intracavernous carotid aneurysms account for 1.9–9.0% of intracranial aneurysms (8–10); their rupture more often leads to a direct CCF than to subarachnoid hemorrhage (11, 12). About 6–9% of intracavernous carotid aneurysms are complicated by a direct CCF (13, 14), whereas aneurysmal CCFs account for about 20% of direct CCFs (7).

Few large series of patients with direct CCF due to aneurysm rupture have been reported. Aneurysmal CCFs sometimes were included as a subtype of spontaneous or direct CCFs (1, 7, 8, 15–19), whereas in other studies they were considered as symptomatic cases of intracavernous aneurysm (13, 14). As a result, reported treatments and outcomes in aneurysmal CCF have been admixed with those of other cases. However, this type of CCF has clinical features distinct from those of dural arteriovenous fistula, and treatment strategies similar to those of traumatic CCF are required.

We evaluated the effectiveness of detachable balloon placement as the treatment of first choice for direct CCFs due to the rupture of an intracavernous carotid aneurysm according to our experiences in six cases that we recently managed. We also compare these cases with our experience in cases of traumatic CCF and review treatment strategies described in the literature.

Methods

Patients treated for spontaneous direct CCF in our institution between 1995 and 2001 included one man and five women with ages ranging from 52 to 83 years (mean, 64.7 years) (Table 1). No patients had a history of head trauma or any family history of connective tissue disease. All patients presented with sudden ocular symptoms including exophthalmos, conjunctival injection, chemosis, and ocular motor palsies.

TABLE 1:

Summary of aneurysmal CCFs

| Case No. | Age (y)/Sex | Symptoms | Materials | Procedure | Outcome | Follow-up Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63/F | Exophthalmos, abducens palsy | Balloon | Aneurysmal occlusion | No shunt, symptom free | Recurrence of aneurysm |

| 2 | 75/M | Exophthalmos, ophthalmoplegia | Balloon | Aneurysmal occlusion | No shunt, abducens palsy | Recurrence of aneurysm Embolization |

| 3 | 54/F | Conjunctival injection, abducens palsy | Balloon | Parent artery occlusion | No shunt, symptom free | |

| 4 | 52/F | Exophthalmos, ophthalmoplegia | Balloon | Aneurysmal occlusion | No shunt, ophthalmoplegia | Recurrence of aneurysm Embolization |

| 5 | 83/F | Exophthalmos, ophthalmoplegia | Coil | Cavernous sinus packing | No shunt, symptom free | |

| 6 | 61/F | Conjunctival injection, abducens palsy | Balloon | Aneurysmal occlusion | No shunt, symptom free |

Endovascular treatment was pursued in all cases. After confirming adequate tolerance of ipsilateral internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion by a balloon occlusion test, transarterial embolization was attempted. Detachable latex balloons (Goldvalve; Nycomed, Paris, France) were used as the embolic material in five patients; in four of these cases the fistula was occluded with preservation of flow in the ICA. All of the balloons were filled with half-concentration contrast medium (iotrolan, Isovist; Schering Osaka, Japan). In the other patient, the cavernous sinus was packed transarterially with coils.

Results

The fistula was occluded in all cases, but the aneurysmal pouch recurred because of spontaneous deflation of the balloon within a few months in three cases. We regarded them as the recanalized aneurysmal pouch according to the findings of pretreatment angiograms. Two of these recurrent aneurysms then were treated by embolization with detachable coils in the usual manner. Exophthalmos and conjunctival injection recovered completely soon after shunt occlusion, but ocular motor palsy failed to improve adequately in two patients. No thromboembolic or hemorrhagic complications occurred. No recurrence of fistulas or neurologic deterioration was observed during follow-up periods of 2–48 months.

Case 1

A 63-year-old woman had sudden onset of right exophthalmos and abducens palsy. About 1 month before this occurrence, an aneurysmal sac had been detected at MR angiography. Initially, this was managed conservatively with observation. On admission, a right ICA angiogram showed a direct CCF with high-flow shunt draining to the superior ophthalmic vein and the inferior petrosal sinus. A round aneurysm approximately 7 mm in diameter was shown in the C5 portion of the right ICA. A detachable balloon was delivered transarterially into the aneurysm, and complete occlusion was achieved. Patency of the parent artery was preserved by using a balloon-assisted neck-plasty technique, in which the detachable balloon was navigated onto the sac, which prevented balloon protrusion to the parent artery during inflation and detachment. All symptoms resolved after this procedure. A repeat angiogram obtained 2 years later showed shrinkage of the balloon and recurrence of the aneurysm, measuring 3 x 5 mm. The patient was observed, since she had no symptoms and the recurrent aneurysm did not change in size on follow-up MR angiograms for 5 years (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Case 1.

A, MR angiogram reveals an aneurysm (arrow) involving the right ICA.

B–D, Angiograms show a right direct CCF with high-flow shunt (B), which clinically was symptomatic. The aneurysm is first opacified in the early phase (C). Obliteration of the shunt is achieved (D).

E, Angiogram obtained 2 years later reveals partial recurrence of the aneurysm

Case 2

A 75-year-old man suddenly developed exophthalmos and total ophthalmoplegia. A right ICA angiogram showed a direct CCF with extremely high shunt flow. The distal portion of the ICA was not opacified; the territory of the ipsilateral ICA was supplied sufficiently by the contralateral ICA. An aneurysm measuring approximately 11 x 12 mm was located in the C3 portion and projected posteroinferiorly. A detachable balloon was delivered transarterially into the aneurysm, and complete obliteration of the shunt was achieved without impairing parent artery flow. Most symptoms improved, but ipsilateral abducens palsy remained. An angiogram 3 months later did not show a shunt, but the aneurysm had recurred owing to shrinkage of the balloon. This aneurysm was embolized easily in the usual manner with detachable coils under the condition of no shunt flow. It was sufficiently packed without impairing the flow in the parent artery although the final coils protruded into the parent artery (Fig 2).

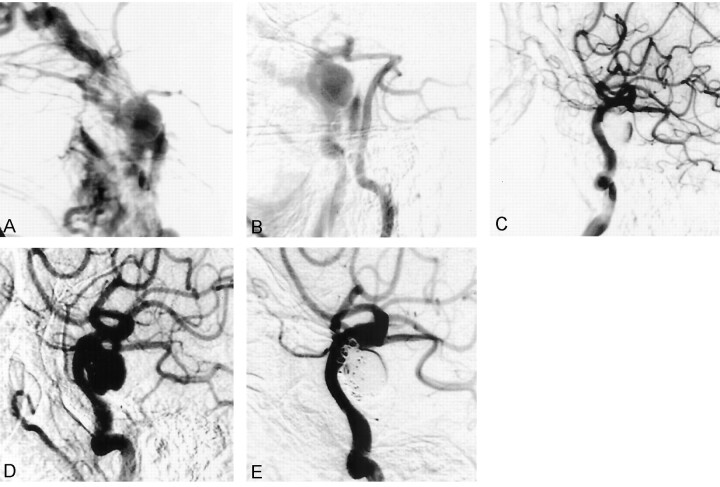

Fig 2.

Case 2.

A, Carotid angiogram shows a direct CCF; the distal portion of the ICA is not opacified because of the high-flow shunt.

B, Right vertebral angiogram depicts the aneurysmal sac by collateral flow upon cross compression.

C, Carotid angiogram obtained just after the procedure shows that a detachable balloon completely occludes the shunt.

D and E, Angiograms obtained 3 months later reveal recurrence of the aneurysm (D), which is packed with coils (E)

Case 3

A 54-year-old woman with sudden onset of left conjunctival injection and abducens palsy showed a high-flow CCF on left ICA angiogram. A detachable balloon was delivered into the aneurysm. The orifice was large, and the space between the orifice and the wall of the cavernous sinus was small; as a result the balloon protruded into the lumen of the parent artery when it was inflated sufficiently to obliterate shunt flow. This situation posed a high risk of distal balloon migration in connection with blood flow, as well as risk of thromboembolism. We did not approach transvenously because the shunt had a large, high flow, causing high risk of coil migration. After confirming sufficient cross flow and ability to tolerate ICA occlusion, the parent artery was occluded together with the shunt by placing the balloon across the orifice. Postoperatively, the patient had no ischemic events, and ocular symptoms resolved within 1 month (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Case 3.

A and B, Left carotid angiograms show a high-flow CCF (A). Shunt flow is nearly obliterated by a detachable balloon, but the orifice is too large to permit complete obliteration. In addition, the space between the orifice and the wall of cavernous sinus is too small to safely position a sufficiently inflated balloon at the fistula (B); further inflation of the balloon can result in migration into the parent artery. Therefore, parent artery occlusion was performed after confirming cross flow with a test occlusion.

Case 4

A 52-year-old woman had left exophthalmos and total ophthalmoplegia of sudden onset. The angiogram showed a left direct CCF with high shunt flow and an aneurysm originating from the C4 portion. The aneurysm was round and about 13 mm in diameter. The fistula was completely obliterated with a detachable balloon delivered through a transarterial route, and the patency of the parent artery was preserved. Although complete obliteration of the shunt flow was achieved, ocular motor palsies persisted. About 1 month later, follow-up angiogram demonstrated recurrence of the aneurysm, associated with shrinkage of the balloon. The recurrent aneurysm was successfully treated with two coil embolization procedures (Fig 4).

Fig 4.

Case 4.

A and B, Left carotid angiograms show a high-flow CCF (A), which is obliterated by a detachable balloon (B).

C and D, Follow-up angiograms obtained 1 month later reveal recurrence of the aneurysmal sac (C), which was embolized with detachable coils (D).

Case 5

An 83-year-old woman with left exophthalmos and ophthalmoplegia underwent angiography, which showed a direct CCF on the left side. Her symptoms occurred suddenly, and she did not have any traumatic episode. A small aneurysm, 2 x 4 mm in diameter and protruding posteromedially, was detected in the C4 to C5 portion on high-speed angiogram. Insertion of a detachable balloon into the aneurysm was impossible, and intrasaccular coil packing seemed to be difficult because the aneurysm was too small. We therefore introduced a microcatheter into this compartment beyond the rupture site and placed detachable coils in the superior ophthalmic vein and anterior portion of cavernous sinus first to prevent cerebral or orbital drainage, and then in the posterior portion, followed by intraaneurysmal packing. Shunt flow was nearly obliterated, and symptoms resolved within a month. She refused any radiographic follow-up, but her symptoms had not recurred for 2 years (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Case 5.

A, Left carotid angiogram shows a direct CCF.

B and C, Oblique views show that the small aneurysm is opacified initially, and then shunt flow is seen.

D–F, Delivery of the detachable balloon fails because of a small orifice, and a microcatheter is advanced into the cavernous sinus (D). The sinus is packed with coils (E), producing nearly complete obliteration (F).

Case 6

A 61-year-old woman had right conjunctival injection and abducens palsy. A right ICA angiogram showed a direct CCF, which drained to the superior ophthalmic vein and to the cerebral deep venous system by cortical reflux. An aneurysm measuring approximately 6 x 7 mm was located in the C4 to C5 portion and protruded medially. A detachable balloon was navigated into the aneurysm by using a balloon-assisted neck-plasty technique. The fistula was occluded completely, and symptoms resolved within a week. Unfortunately, she was lost to follow-up after leaving our hospital (Fig 6).

Fig 6.

Case 6.

A, Right carotid angiogram shows a direct CCF mainly draining to the superior ophthalmic vein. A microcatheter is inserted into the ruptured aneurysmal sac.

B, Fistula disappears after treatment with a detachable balloon, without impairing carotid artery flow.

Discussion

Indications for Treatment

Signs of CCF feature a triad of pulsatile exophthalmos, orbital bruit, and conjunctival injection. Ocular motor palsy, ocular pain, and visual impairment also occur frequently. Indications for aggressive treatment include visual impairment, progressive paresis of extraocular muscles, intractable orbital pain or bruit, and progressive or severe exophthalmos (15, 16). In particular, CCF with cortical venous reflux or ischemia due to steal phenomena should be treated urgently. In our series, all patients had ocular motor palsy and exophthalmos, and aggressive treatment was indicated.

Treatment Options

Spontaneous regression of direct CCF is uncommon (1, 17, 20), in contrast to the course of many dural-type arteriovenous fistulas. Various surgical approaches have been developed. In 1973, Parkinson (21) reported successful direct surgical repair of direct CCFs with preservation of the parent artery. However, the technical difficulty and high invasiveness of this procedure have precluded wide adoption of this surgical treatment. Subsequently, other direct interventional treatments have been attempted such as electrothrombosis with use of a copper wire inserted directly into the cavernous sinus by a stereotactic method or through the superior ophthalmic vein (22, 23). Since Serbinenko (24) reported his experience with a detachable balloon, endovascular treatment has become the first choice for the treatment of direct CCF.

For endovascular surgery, multiple options exist with respect to materials as well as routes of approach. Two general types of embolic material, detachable balloon and detachable coils, are available. Fistula occlusion using a detachable balloon delivered by a transarterial route is the preferred method for treating direct CCF (2, 7, 16, 18, 25). Materials for detachable balloons include latex and silicone. Of these, latex balloons are available in many different shapes and sizes (7, 26) and show higher elasticity (26), higher thrombogenecity, and more rapid endothelialization (27). We therefore used latex balloons for five aneurysms. As contents of the balloon, we always use an intermediate concentration of contrast medium as opposed to a polymerizing substance such as hydromethylmethacrylate. Balloons inflated with polymers remain permanently solid, which may impede recovery from ocular palsy (26, 27); however, balloons filled with contrast medium may deflate within a few months, resulting in recurrence of aneurysms. Very importantly, latex balloons can be inflated only with contrast medium, since polymers damage these balloons (28, 29). All but one of our current patients were treated with latex balloons. Three of these four aneurysms with such saccular occlusion sparing parent artery patency recurred after spontaneous balloon deflation, but the fistula remained occluded with no resumption of shunt flow. Embolization of these recurrent aneurysms using detachable coils was easy given elimination of coil migration, which may complicate embolization under conditions of high shunt flow.

In some instances, the balloon may protrude into the lumen of the ICA when inflated sufficiently to occlude shunt flow. For such cases, a balloon-assisted neck-plasty technique may sometimes be helpful, as in our cases 1 and 6. In some other cases in which the balloon protrudes, occlusion of the ICA may be the best alternative; turbulent flow around a protruding balloon can cause thromboembolism or distal migration of the balloon itself (7). If the patient does not tolerate a test balloon occlusion, a procedure to supply sufficient collateral flow, such as high-flow bypass, must be performed before the occlusion.

Transarterial cavernous sinus packing with detachable coils is another useful method (17, 30, 31), particularly for small to medium fistulas with limited shunt flow (31). A microcatheter can be navigated over a guidewire into the cavernous sinus through an orifice too small to introduce a detachable balloon (31). In some cases with low shunt flow, aneurysm packing with coils may suffice (32, 33). However, the optimal volume of coils to be embolized is difficult to determine (17, 31). A more serious disadvantage is the risk of coil migration (16, 30, 33) given persistent shunt flow because flexible coils may be carried out through the sinus owing to high shunt flow, whereas an inflated balloon as one mass has less risk of migration because it might be supported by aneurysmal wall or intracavernous trabeculae. Therefore, we use the coil method as the second choice when balloon placement has failed.

Approach Route

A transarterial approach is recommended for balloon embolization (16, 25) since manipulation depends on the direction of the blood flow, although transvenous embolization for traumatic direct CCF has been reported (2, 7, 16, 25, 34). For coil embolization, a transarterial approach also is essentially recommended, except in cases of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with a fragile arterial wall (3); embolization of the sac of the aneurysm by a transvenous approach is difficult, and a large volume of coils may be required to pack the cavernous sinus. This carries a risk of aggravating ocular symptoms if the posterior drainage is occluded without precise control of shunt flow. However, the transvenous approach is an available and useful method when a transarterial approach is very difficult or not indicated (2, 25, 34).

Disruption of shunt flow resulted in dramatic improvement of ocular symptoms in all of our cases, except that ocular palsy did not always decrease. Indeed, Klisch et al (35) and Debrun et al (36) reported on cases with deterioration of ocular palsy, probably because of overinflation of the balloon. In two of our patients (cases 3 and 4) without satisfactory improvement, the aneurysms were relatively large and coil embolization was necessary following deflation of the balloons; this is one limitation of balloon embolization. Transvenously overpacked coils also may prolong nerve compression, resulting in the irreversible change.

We achieved fistula occlusion with preservation of the parent artery in five (83%) of six cases; four (80%) of these five fistulas were occluded by using detachable balloons only. In the same period, we experienced 17 cases of traumatic direct CCF, in which the rate of ICA preservation was only 53% (nine cases). Only five (55%) of these nine fistulas could be treated with a detachable balloon alone; some cases needed cavernous sinus packing with coils (Table 2). Treatment of traumatic CCF appears to be more difficult than that for aneurysmal cases. The likely explanation is that in carotid trauma the contour of the fistula orifice is irregular, so the round balloon cannot completely cover the orifice; in aneurysmal CCF the orifice is round and the aneurysmal wall except for the ruptured point may support the balloon, therefore occlusion by the balloon is easier. Conversely, aneurysmal CCF may be more suitable for treatment with detachable balloons.

TABLE 2:

Materials used for fistula occlusion

| Material | Aneurysmal CCF (n = 6) | Traumatic CCF (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 5 (83) | 9 (53) |

| Balloon | 4 (80) | 5 (55) |

| Balloon + coil | 0 (0) | 3 (33) |

| Coil | 1 (20) | 1 (11) |

Note.—Numbers in parentheses are percentages.

Recently, new techniques for preserving patency of the parent artery have been reported. Morris (37) reported a case of traumatic direct CCF successfully treated with coils by using a balloon remodeling technique, whereas Redekop et al (38) treated traumatic arteriovenous fistulas with porous or covered stents. More success can be anticipated as new treatment options develop in addition to the commonly used detachable balloons.

Conclusion

For treatment of CCF caused by the rupture of aneurysms, placement of detachable balloons is the treatment of first choice to achieve immediate shunt occlusion, although the parent artery occasionally must be occluded. Detachable coils are valuable if balloon placement fails to permanently obliterate the aneurysm and sometimes when parent artery occlusion would be required but cannot be tolerated. More frequent preservation of parent artery patency should be permitted by development of new techniques to place other devices such as covered stents.

References

- 1.Barrow DL, Spector RH, Braun IF, Landman JA, Tindall SC, Tindall GT. Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. J Neurosurg 1985;62:248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Hieshima GB, Hardin CW, Yang PJ. Transvenous embolization of direct carotid cavernous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1988;9:741–747 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanner AA, Maimon S, Rappaport ZH. Treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistula in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome by transvenous occlusion with Guglielmi detachable coils: case report. J Neurosurg 2000;93:689–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debrun GM, Aletich VA, Miller NR, DeKeiser RJW. Three cases of spontaneous direct carotid cavernous fistulas associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Surg Neurol 1996;46:247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.d’Angelo VA, Monte V, Scialfa G, Fiumara E, Scotti G. Intracerebral venous hemorrhage in “high-risk” carotid-cavernous fistula. Surg Neurol 1988;30:387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesoin F, Rousseau M, Petit H, Jomin M. Spontaneous development of an intracavernous arterial aneurysm into a carotid-cavernous fistula: case report. Acta Neurochirurgia 1984;70:53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis AI, Tomsick TA, Tew JM Jr. Management of 100 consecutive direct carotid-cavernous fistulas: results of treatment with detachable balloons. Neurosurgery 1995;36:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polin RS, Shaffrey ME, Jensen ME, et al. Medical management in the endovascular treatment of carotid-cavernous aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1996;84:755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linskey ME, Sekhar LN, Hirsch W Jr, Yonas H, Horton JA. Aneurysm of intracavernous carotid artery: clinical presentation, radiographic features, and pathogenesis. Neurosurgery 1990;26:71–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linskey ME, Sekhar LN, Hirsch W Jr, Yonas H, Horton JA. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery: natural history and indications for treatment. Neurosurgery 1990;26:933–938 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishioka T, Kondo A, Aoyama I, Nin K, Takahashi J. Subarachnoid hemorrhage possibly caused by a saccular carotid artery aneurysm within the cavernous sinus: case report. J Neurosurg 1990;73:301–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AG, Mawad M, Baskin DS. Fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage from the rupture of a totally intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery 1996;38:596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higashida RT, Halbach VV, Dowd C, et al. Endovascular detachable balloon embolization therapy of cavernous carotid artery aneurysms: result in 87 cases. J Neurosurg 1990;72 .857–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupersmith MJ, Hurst R, Berenstein A, Choi IS, Jafar J, Ransohoff J. The benign course of cavernous carotid artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1992;77:690–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinuela F, Fox AJ, Debrun GM, Peerless SJ, Drake CG. Spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistulas: clinical, radiological, and therapeutic considerations: experience with 20 cases. J Neurosurg 1984;60:976–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinugasa K, Tokunaga K, Kamata I, et al. Selection and combination of techniques for treating spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. Neurol Med Chir(Tokyo) 1994;34:597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momoji J, Mukawa J, Yamashiro K, et al. Transarterial platinum coil embolization for direct carotid-cavernous fistula [in Japanese]. No to Shinkei 1997;49:85–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debrun GM, Vinuela F, Fox AJ, Davis KR, Ahn HS. Indication for treatment and classification of 132 carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgery 1988;22:285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurata A, Miyasaka Y, Kunii M, et al. The value of long-term clinical follow-up for cases of spontaneous carotid cavernous fistula. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halbach VV, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, Reicher M. Carotid cavernous fistulae: indication for urgent treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson D. Carotid cavernous fistula: direct repair with preservation of the carotid artery—technical note. J Neurosurg 1973;38:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullan S. Experiences with surgical thrombosis of intracranial berry aneurysms and carotid cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg 1974;41:657–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosobuchi Y. Electrothrombosis of carotid-cavernous fistula. J Neurosurg 1975;42:76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serbinenko FA. Balloon catheterization and occlusion of major cerebral vessels. J Neurosurg 1974;41:125–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goto K, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, et al. Treatment of direct carotid cavernous sinus fistulae: various therapeutic approaches and results in 148 cases. Acta Radiol (suppl) 1986;369:576–579 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debrun GM. Treatment of traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula using detachable balloon catheters. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1983;4:355–356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyachi S, Negoro M, Handa T, Terashima K, Keino H, Sugita K. Histopathological study of balloon embolization: silicone versus latex. Neurosurgery 1992;30:483–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monsein LH, Debrun GM, Chazaly JR. Hydroxyethyl methylacrylate and latex balloons. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990;11:663–664 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsting M, Sartor K. Hema and latex: a dangerous combination? Neuroradiology 1991;33:338–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Barnwell SL, Dowd CF, Hieshima GB. Transarterial platinum coil embolization of carotid-cavernous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12:429–433 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siniluoto T, Seppanen S, Kuurne T, Wikholm G, Leinonen S, Svendsen P. Transarterial embolization of a direct carotid cavernous fistula with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:519–523 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanke I, Doerfler A, Stolke D, Forsting M. Carotid cavernous fistula due to a ruptured intracavernous aneurysm of the internal carotid artery: treatment with selective endovascular occlusion of the aneurysm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:784–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Briganti F, Duckwiler G. Carotid-cavernous fistula caused by a ruptured intracavernous aneurysm: endovascular treatment by electrothrombosis with detachable coils. Neurosurgery 1992;31:591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu T, Waga S, Kojima T, Tanaka K. Transvenous Balloon occlusion of the cavernous sinus: an alternative therapeutic choice for recurrent traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgery 1988;22:550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klisch K, Schipper J, Husstedt H, Laszig R, Schumacher M. Transsphenoidal computer-navigation-assisted deflation of a balloon after endovascular occlusion of a direct carotid cavernous sinus fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:537–540 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debrun G, Lacour P, Vinuela F, Fox A, Drake CG, Caron JP. Treatment of 54 traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg 1981;55:678–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris PP. Balloon reconstructive technique for the treatment of a carotid cavernous fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1107–1109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Redekop G, Marotta T, Weill A. Treatment of traumatic aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas of the skull base by using endovascular stents. J Neurosurg 2001;95:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]