Abstract

Schools have been closed across the country and will remain closed until September in most provinces. The decision to reopen should take into account current inequalities in cognitive skills across the country and the impact of school interruptions on knowledge accumulation. In this article, we use information from a companion article to estimate the socioeconomic achievement gaps of 15-year-olds across Canada and assess the impact of the pandemic on inequalities in education. Using estimates from the literature on the impact of school closures, we find that the socioeconomic skills gap measured using Programme for International Student Assessment data could increase by more than 30 percent.

Keywords: cognitive skills, socioeconomic inequalities, PISA, pandemic, Canadian provinces

Abstract

Les écoles ont été fermées partout au pays et le demeureront jusqu’en septembre dans la plupart des provinces. Dans la décision de rouvrir les écoles, il faudra tenir compte des inégalités actuelles au chapitre des habiletés cognitives des élèves dans l’ensemble du Canada et de l’incidence de l’interruption du fonctionnement des écoles sur le cumul des connaissances. Les auteurs utilisent l’information provenant d’un document complémentaire pour estimer l’écart socioéconomique dans la réussite des jeunes de 15 ans sur l’ensemble du territoire canadien et évaluent les répercussions de la pandémie sur les inégalités dans l’éducation. À l’aide d’estimations tirées de la documentation sur les conséquences de la fermeture des écoles, les auteurs prévoient que les écarts socioéconomiques de compétences mesurés selon les données du PISA pourraient croître de plus de 30 pour cent.

Mots clés : habilités cognitives, inégalités socioéconomiques, pandémie, PISA, provinces canadiennes

Introduction

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, primary and secondary schools across Canada have been closed, yet school interruptions are known to have short and long-term negative effects on students’ academic outcomes and perseverance (e.g., Belot and Webbink 2010; Meyers and Thomasson 2017). These effects differ by socioeconomic status (SES), and therefore school interruptions have the potential to exacerbate inequalities among students. As a result, the decision to reopen schools across the country should take into account both health concerns related to the propagation of the virus and the impact of school closures on inequalities in education across the country. Using Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data, combined with the approach used in a companion article (Haeck and Lefebvre 2020) on SES achievement gaps of 15-year-olds across Canada, we provide a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the impact of the pandemic on SES inequalities in education.

School Interruptions, a Brief Review

The literature shows that school interruptions can have a negative impact on students’ academic skills and perseverance (e.g., Cooper et al. 1996; Meyers and Thomasson 2017; Belot and Webbink 2010), and these impacts may differ by socioeconomic status. Several strategies have been used to document the impact of school interruptions on academic achievement.

The literature that exploits summer learning losses finds mixed results on average, but seems to suggest that mean declines or stagnation typically hide differences by socioeconomic status (see Atteberry and McEachin forthcoming for a complete review). Many recent studies refer to kindergarten children (e.g. Downey, Von Hippel, and Broh 2004; Von Hippel and Hamrock 2019), who are not our main focus here. Atteberry and McEachin (forthcoming) exploit data on over 200 million test scores in 32,000 schools across the United States between 2008 and 2016. They find mean summer losses in grades 1 to 8 in both mathematics and English, and the variance of summer learning losses is large. Some students lose a lot of ground, while others gain some ground. Race and SES only explain a small fraction of the variance, but they certainly do play a role. Cooper et al. (1996) review the literature on school interruptions during the summer and find that students lose about one month of equivalent schooling over the summer. Their meta-analysis also suggests that the impact is steeper in higher grades and losses are more important in mathematics than in reading. Finally, they document a differential impact on reading based on the SES of the students. More specifically, they find that students from low-income families experience a decline in their reading skills (−1.5 months), while students from middle- to high-income families experience an improvement in their reading skills over the summer (+2.3 months). Studies used in Cooper et al. (1996) are dated; most were conducted in the 1980s. Their findings may not apply in the current context. On one hand, given that the labour force participation of mothers has increased over the last 30 years, mothers may not be as available during the summer months to supervise their children and, therefore, the learning loss may be greater now than before. At the same time, families with dual-income parents have more income resources than ever before, and they may therefore be able to provide an enriched environment during the summer months. Finally, in the specific context of the pandemic, more educated parents are more likely to have flexible jobs and have access to resources to help their children, including Internet-enabled personal computers or laptops, which are more conducive than mobile devices to producing information (Frenette, Frank, and Deng 2020). In this sense, the impact may in fact be even greater than suggested in Cooper et al. (1996), as parents may get more involved than they normally would during the summer. In addition to Cooper et al. (1996), Davies and Aurini (2013) study learning inequalities over the summer in Ontario. They also find evidence suggesting that socioeconomic disparities in literacy tend to increase over the summer.

Instead of using summer learning losses, Frenette (2008) uses a different identification strategy, but comes to a similar conclusion. He exploits regulations around school entry age to document the impact of instructional time. He finds that one year less of schooling is associated with a score that is 6 percent lower in reading, 5.9 percent lower in math, and 4 percent lower in science.

Educational attainment may also be impacted by school closures. Meyers and Thomasson (2017) study the impact of school closures during the 1916 polio pandemic. School closures occurred at the beginning of the school year and lasted only a few weeks, yet they had devastating effects on school perseverance. They find that school closures reduced educational attainment of children aged 14 to 17 during the pandemic, but not that of younger children. They find that a one-standard-deviation increase in the number of polio cases caused 1 in every 14 students to achieve one less year of schooling. This is an important lesson for high schools come September.

Finally, Belot and Webbink (2010) study teachers’ strikes in Belgium in 1990 and reach a similar conclusion: school interruptions affect educational attainment in a permanent way. Baker (2013) and Johnson (2011) also exploit teachers’ strikes using school-level data on grade 3 and 6 students in Ontario. Baker (2013) documents that long strikes of ten days or more have large negative impacts on test score growth. Johnson (2011) finds that school interruptions caused by teachers’ strikes negatively affect the pass rate on provincial exams and that those effects are concentrated among students in disadvantaged schools.

Pandemic and Educational Inequalities

In our companion article (Haeck and Lefebvre 2020), we document the evolution of the achievement gap over time between low- and high-SES students using microdata from PISA. PISA is a triennial survey of the skills of 15-year-olds in three domains: reading, mathematics, and science. Canada is one of the top performing OECD countries. In 2018, Canada obtained a score of 520 points in reading, 512 points in mathematics, and 518 points in science, relative to an OECD average score around 485 points in 2018 (O’Grady et al. 2019). Here, we present the average achievement gap by SES. To do so, we estimate the following equation for Canada and also for each province separately:

| (1) |

Si,py is the PISA test score of student i in province p in mathematics, reading, or science in year y. The equation is estimated for each survey year, but also by pooling all survey years and adding year fixed effects. The SES index is measured by the Highest International Socio-economic Index of Occupational Status (HISEI) and transposed in quintiles.1 As a result, the term SESq,i represents four dummy variables, one for each of the top four quintiles of the HISEI index. The reference group is therefore the bottom quintile of the index, which represents students whose parents have the lowest occupational status. Following our companion article, the quintiles are measured at the provincial level, but measuring them at the national level provides extremely similar results. The vector Xi includes student gender, age in months, and expected grade, along with a dummy for immigration status, and two dummies indicating the language spoken at home (French, English, and others as the reference). Survey weights, plausible values, and bootstrapped weights derived by the OECD are used in the estimation procedure (refer to the PISA technical reports for more information). Table 1 presents the estimated SES coefficient for Canada for all survey years (top panel) and also for 2018 only (bottom panel).

Table 1:

SES Gradient in Canada

| SES | Math |

Reading |

Science |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| All years | ||||||

| Q2 | 19.18 | 1.28 | 21.33 | 1.17 | 18.15 | 3.33 |

| Q3 | 31.44 | 1.23 | 35.05 | 1.24 | 35.48 | 3.46 |

| Q4 | 43.47 | 1.20 | 48.55 | 1.20 | 47.32 | 3.39 |

| Q5 | 58.79 | 1.36 | 63.12 | 1.42 | 59.97 | 3.55 |

| 2018 | ||||||

| Q2 | 19.03 | 2.90 | 20.38 | 3.15 | 18.15 | 3.33 |

| Q3 | 35.50 | 3.55 | 38.05 | 3.45 | 35.48 | 3.46 |

| Q4 | 48.17 | 3.02 | 50.39 | 3.26 | 47.32 | 3.39 |

| Q5 | 62.17 | 3.42 | 62.66 | 3.56 | 59.97 | 3.55 |

Notes: This table presents only the estimated coefficients on the SES quintile dummies. The top panel pools all survey years together. The bottom panel is based on PISA 2018 data only. The reference group for the SES quintiles is Q1 (the bottom quintile, including students whose parents have the lowest occupational status). Year fixed effects are included when all years are pooled together (top panel). Both models include the following control variables: student gender, age in months, expected grade, a dummy for immigration status, and two dummies indicating the language spoken at home (French, English, and others as the reference).

Source: Author’s calculations.

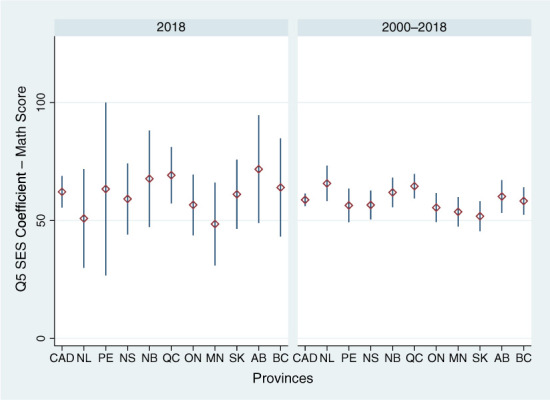

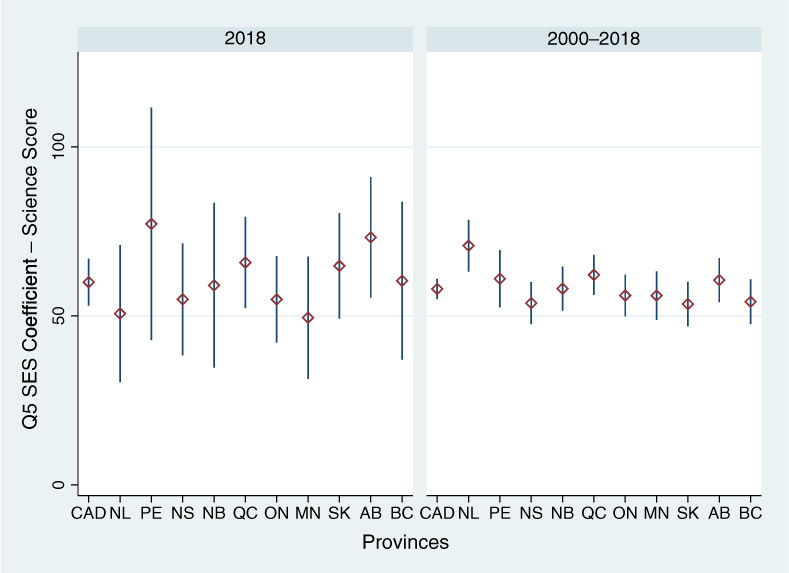

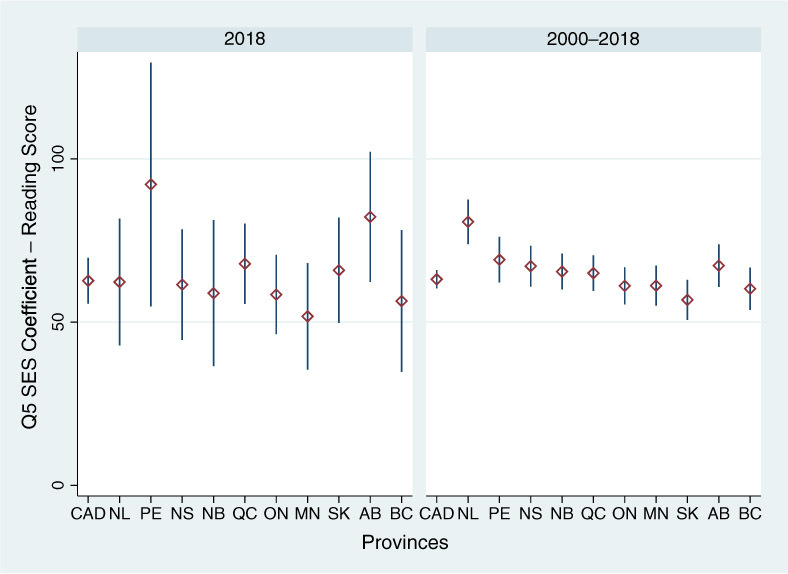

Results from Table 1 suggest that, in reading, students with parents in the second quintile (Q2) of the SES index obtain an average score that is 21.3 points higher than that for students of Q1 parents. At the top end of the distribution, students of parents in the highest quintile (Q5) generally obtain 63.1 points more on average. The PISA Technical report (OECD 2010) states that a 40-point difference in test scores is approximately equivalent to one additional year of schooling. In this sense, the SES gap we identify represents more than a year of schooling. In mathematics, the SES gradient is not as steep, from 19.2 points for Q2 relative to Q1 to 58.8 points for Q5 relative to Q1. Finally, in science, we find a SES gradient from 18.1 points in Q2 to 60.0 points in Q5. Similar gradients are observed in all ten provinces, with some variation across domains (see Figures 1–3).2 Using only data from PISA 2018, we find similar gradients, slightly higher in magnitude but not statistically significantly different.

Figure 1:

Q5 versus Q1 SES Gradient across Canada—Mathematics Scores

Notes: Estimated SES Q5 coeffi cients. See note to Table 1 for list of control variables. The acronyms used for each province and Canada are: CAD = Canada, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, PE = Prince Edward Island, NS: Nova Scotia, NB = New Brunswick, QC = Québec, ON = Ontario, MN = Manitoba, SK = Saskatchewan, AB = Alberta, and BC= British Columbia.

Source: Author’s calculations.

Figure 3:

Q5 versus Q1 SES Gradient across Canada—Science Scores

Notes: Estimated SES Q5 coeffi cients. See note to Table 1 for list of control variables and the note to Figure 1 for the list of acronyms.

Source: Author’s calculations.

Because school interruptions across the country due to the pandemic will be of at least 3.2 months (5.5 months in total minus a summer period of 2.3 months),3 using Cooper et al.’s estimates, we can expect academic skills in reading and math to decrease by an additional 1.4 months,4 which would represent about 6 points on the average PISA score. As mentioned above, Cooper et al. (1996) is somewhat dated. To validate these findings, we use the estimates produced by Frenette (2008). Because one year less of schooling is associated with a decrease of 6 percent in reading, 5.9 percent in mathematics, and 4 percent in science, and the average PISA 2018 score in Canada was 520 in reading, 512 in mathematics, and 518 in science, we estimate that an interruption of 3.2 months would represent a drop of 10 points in reading, 10 points in mathematics, and 7 points in science. The two studies lead to similar estimates.

These average impacts may mask important differences by SES. Using the SES estimates of Cooper et al. (1996), we find that students from low-income families may see their overall reading score decline by an additional 2 months (or −8 points), while other children may gain 3.2 months (or +12.8 points). This would increase the score gap between Q1 and Q5 students by 20.8 points, an increase of more than 30 percent relative to the actual SES gap in Canada. Because online teaching has taken place in some provinces, students have not been left completely idle. A drop of 30 percent may therefore be a worst-case scenario. At the same time, given differential access to technology and parental support by SES, it may also be a fairly realistic estimate.

More recently, Davies and Aurini (2013) studied learning inequalities over the summer in Ontario. They also found evidence suggesting that socioeconomic disparities in literacy tend to increase over the summer. They find that children in affluent families gain literacy skills over the summer while those from the bottom SES quartile lose skills. According to their results, 25 percent of the observed skills gap by SES at the beginning of the school year is explained by differential summer learning by SES. Their results are in line with our above estimate for the pandemic.

On school perseverance, we can also expect a large negative impact. This is worrisome in general, but even more so in provinces where the high school dropout rate is higher. The on-time completion rate is lowest in Québec (Statistics Canada 2018). Our companion article (Haeck and Lefebvre 2020) shows that this is also the province in which the largest fraction of 15-year-olds are in a school grade that is lower than their birth dates would predict. Major human and financial resources will be needed in the fall to help students persevere and succeed across the country, but the need may be more severe in some provinces.

As a final note, we would like to point interested readers to Escueta et al. (forthcoming), a brilliant review of 126 studies on education technologies using controlled trials. The authors point out that the effectiveness of online learning is highest if it is combined with incentives to learn and interact. Teachers need to learn how to use technology to provide online teaching and they need to provide retroaction to keep students engaged. Teachers’ responses will determine the depth of the impacts on the SES gap across the country. PISA 2021 survey data will be a valuable source to evaluate our successes and our failures.

Concluding Remarks

Canada is one of the most strongly performing OECD countries in the PISA results. However, these results mask important differences by SES. The pandemic brings important challenges to our provincial education systems. Our back-of-the-envelope calculation revealed that the SES score gap could increase by as much as 30 percent. School interruption is likely to impact perseverance in high school. A recent study of the polio pandemic of 1916 showed that a few weeks of interruption at the beginning of the school year caused a significant reduction in school attainment among high school students. Clearly, incentives to graduate from high school have evolved since 1916, but the duration of school interruptions is dramatically larger in this pandemic than it was back then.

Inequalities in skills are not a contemporaneous problem that will be easily reabsorbed. Skills acquired early in life beget skills over the life cycle, so that skills inequalities generally translate into income inequalities (e.g., Carneiro and Heckman, 2003; Chetty et al. 2011). On a macroeconomic scale, Hanushek and Woessmann (2015a, 2015b) have also shown that skills measured using PISA data are associated with our ability to generate economic growth.

Our lack of knowledge of the epidemiology of the virus among children, teenagers, and teachers at the start of the pandemic appropriately led to our collective decision to close schools across the country. As our knowledge evolves on the transmission and severity of the virus, so that our decisions are being reassessed, it will be important to factor in the impact of school closures on academic inequalities and their long-term consequences.

While rising inequalities resulting from the pandemic should be our primary concern, we also need to remember that inequalities in academic achievement observed throughout the PISA surveys highlight a lingering issue that we will still need to address post-pandemic. Innovative actions will need to be taken across our educational system to mitigate the potential rise in achievement gaps by SES during the pandemic, but also beyond it.

Figure 2:

Q5 versus Q1 SES Gradient across Canada—Reading Scores

Notes: Estimated SES Q5 coeffi cients. See note to Table 1 for list of control variables and the note to Figure 1 for the list of acronyms.

Source: Author’s calculations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This analysis is based on Statistics Canada’s surveys, which produced PISA data sets for the departments of education of the Canadian provinces and the OECD consortium. All computations on these microdata were prepared by the authors, who assume responsibility for the use and interpretation of these data. This research was funded by two research grants from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Société et Culture (FRQSC), Subvention Soutien aux équipes de recherche et Subvention Action concertée, Programme de recherche sur la pauvreté et l’exclusion sociale, Phase 4.

Notes

This choice is explained in detail in Haeck and Lefebvre (2020).

Data behind the figures, and additional models, are available in the supplementary material in the online Appendix and at Groupe de recherche sur le capital humain (n.d., Working Paper 20-03).

We do not include the summer months, because these happen every year and are embedded in the observed gap.

A negative impact of one month over 2.3 months of summer multiplied by an additional 3.2 months of school closure due to the pandemic.

Contributor Information

Catherine Haeck, Department of Economics, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, Québec.

Pierre Lefebvre, Department of Economics, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, Québec.

References

- Atteberry, A., and McEachin A.. forthcoming. “School’s Out: The Role of Summers in Understanding Achievement Disparities.” American Educational Research Journal. 10.3102/0002831220937285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. 2013. “Industrial Actions in Schools: Strikes and Student Achievement.” Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique 46(3):1014–36. 10.1111/caje.12035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belot, M., and Webbink D.. 2010. “Do Teacher Strikes Harm Educational Attainment of Students?” Labour Economics 24(4):391–406. 10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00494.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, P., and Heckman J.J.. 2003. “Human Capital Policy.” In Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies? ed. Friedman B.M., 77–239. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R., Friedman J., Hilger N., Saez E., Schanzenbach D., and Yagan D.. 2011. “How Does Your Kindergarten Classroom Affect Your Earnings? Evidence from Project STAR.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(4):1593–1660. 10.3386/w16381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H., Nye B., Charlton K., Lindsay J., and Greathouse S.. 1996. “The Effects of Summer Vacation on Achievement Test Scores: A Narrative and Meta-Analytic Review.” Review of Educational Research 66(3):227–68. 10.3102/00346543066003227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S., and Aurini J.. 2013. “Summer Learning Inequality in Ontario.” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de politiques 39(2):287–307. 10.3138/cpp.39.2.287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downey, D.B., Von Hippel P.T., and Broh B.A.. 2004. “Are Schools the Great Equalizer? Cognitive Inequality during the Summer Months and the School Year.” American Sociological Review 69(5):613–35. 10.1177/000312240406900501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escueta, M., Nickow A.J., Oreopoulos P., and Quan V.. Forthcoming. “Upgrading Education with Technology: Insights from Experimental Research.” Journal of Economics Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Frenette, M. 2008. “The Returns to Schooling on Academic Performance: Evidence from Large Samples around School Entry Cut-off Dates.” Cat. No. 11F0019M No. 317. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Frenette, M., Frank K., and Deng Z.. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic: School Closures and the Online Preparedness of Children.” Statistics Canada, Social Analysis and Modeling Division. 15 April. At https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00001-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Groupe de recherche sur le capital humain . n.d. Publications. At https://grch.esg.uqam.ca/en/publications/.

- Haeck, C., and Lefebvre P.. 2020. “The Evolution of Cognitive Skills Inequalities by Socioeconomic Status across Canada.” Working Paper 20-04, Research Group on Human Capital. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E., and Woessmann L.. 2015. a. The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E., and Woessmann L.. 2015. b. Universal Basic Skills: What Countries Stand to Gain. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. 2011. “Do Strikes and Work-to-Rule Campaigns Change Elementary School Assessment Results?” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de politiques 37(4):479–94. 10.3138/cpp.37.4.479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, K., and Thomasson M.A.. 2017. “Panics, Quarantines, and School Closures: Did the 1916 Poliomyelitis Epidemic Affect Educational Attainment?” NBER Working Paper # 23890.

- OECD . 2010. PISA 2009 Results−Learning to Learn: Student Engagement Strategies and Practices, Volume 3. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, K., Deussing M.-A., Scerbina T., Tao Y., Fung K., Elez V., and Monk J.. 2019. “Measuring Up: Canadian Results of the OECD PISA 2018 Study: The Performance of Canadian 15-Year-Olds.” Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . 2018. “Education Indicators in Canada: An International Perspective, 2018.” 11 December. At https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-604-x/81-604-x2018001-eng.htm.

- Von Hippel, P., and Hamrock C.. 2019. “Do Test Score Gaps Grow before, during, or between the School Years? Measurement Artifacts and What We Can Know in Spite of Them.” Sociological Science 6:43–80. 10.15195/v6.a3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.