Abstract

The current coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has a high spreading and fatality rate. To control the rapid spreading of the COVID-19 virus, the government of India imposed lockdown policies, which creates a unique opportunity to analyze the impact of lockdown on air quality in the two most populous cities of India, i.e., Delhi and Mumbai. To do this, the study employed a spatial approach to examine the concentration of seven criteria pollutants, i.e., PM2.5, PM10, NH3, CO, NO2, O3, and SO2, before, during, and after a lockdown in Delhi and Mumbai. Overall, around 42%, 50%, 21%, 37%, 53%, and 41% declines in PM2.5, PM10, NH3, CO, NO2, and SO2 were observed during the lockdown period as compared to previous years. On the other hand, a 2% increase in O3 concentration was observed. However, the study analyzed the National Air Quality Index (NAQI) for Delhi and Mumbai and found that lockdown does not improve the air quality in the long term period. Our key findings provide essential information to the cities' administration to develop rules and regulations to enhance air quality.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Air quality, India, Spatial analysis

1. Introduction

Air pollution is one of the biggest challenges humankind is facing in the 21st century, and it has had various direct or indirect effects on human health. The air pollution levels in megacities of the world exceed the air quality standards recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and even the pollution concentration in some cities exceeds ten times more than the standard level (Marlier et al., 2016). The air contains acidic substances such as CO, NH3, PM2.5, PM10, NO2, etc., which can cause widespread effects on human health. Long-term inhalation of polluted air can cause lung cancer, stroke, and heart disease, as well as heart failure. These pollutants are mainly emitted from human actions like the burning of fossil fuel, transportation, manufacturing process, and deforestation (Blondet et al., 2019; Kinnon et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019). Air pollution damages the health of about 1 billion people and kills around 7 million people every year (WHO, 2014).

Since the outbreak of coronavirus disease, 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China, numerous health, economic, and social issues have been arising (Khoo and Lantos, 2020; C. Wang et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). As of January 30, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a global health emergency. Besides China, it has also severely affected the whole world. Covid-19 not only cause pneumonia but also damages the liver, heart, and kidney, leading to multiple organ disorders and ultimately leading to death. Globally, as of September 15, 2020, there have been 29.16 million confirmed cases, including 0.93 million deaths (WHO, 2020), out of which India has reported 4.93 million confirmed cases and 80776 death. Thus, India is accounted for 16.91 percent, and 8.72 percent of worldwide COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths, respectively.

Megacities of the world are facing severe environmental challenges due to industrial waste and vehicle emissions (Yang et al., 2020). However, after the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries put restrictions on all business activities, including transportations (land, sea, air), manufacturing industries, construction, and mining activities. Globally, a significant decline in air pollution has been observed, such as in Japan (Ma and Kang, 2020), Brazil (Dantas et al., 2020), Spain (Baldasano, 2020), China (Bao and Zhang, 2020), India (Mahato et al., 2020; Shehzad et al., 2020), and the United States (Pata, 2020; Sarfraz et al., 2020). Consequently, low environmental pollution has a positive impact on human health, and it helps human immunity to resist the virus (Yang and Liu, 2018). Moreover, Chakraborty and Maity (2020) argue that lockdown amidst COVID-19 is offering short-term benefits to air quality and human health. Still, it owns the double edge threat from the perspective of the long-run aspect. First, ongoing efforts towards climate mitigation are adversely affected due to economic slowdown; besides, rising health issues along with financial fear (recession) could overshadow the problem of climate change. Second, the sudden resumption of businesses after the lockdown will put massive pressure on the environment.

The Indian economy is undergoing the phase of industrialization and modernization, due to which its hazardous air pollution is somewhat similar to the industrial revolution in Europe (Mahato et al., 2020). Moreover, Delhi and Mumbai are among the most polluted megacities (WHO, 2018). After the emergence of COVID-19, nation wise lockdown was imposed in India during March 2020 (Table 1 ), which created a unique opportunity to gauge the impact of lockdown on air quality in Delhi and Mumbai. Overall the effect and significance of lockdown are still not well understood and likely to have a significant role in the restoration of air quality. Limited studies examine the impact of lockdown on air quality in mega cites around the world, but the evidence of Delhi and Mumbai is still missing. The prevailing literature on the impact of lockdown on air quality has only been observed on one or two pollutants. Although discussing the air quality, concentrating solely on one or two pollutants cannot provide a holistic picture. Moreover, none of the studies examined the concentration of pollutants after the lockdown period. Therefore, this study analyzes the impact of lockdown in Delhi and Mumbai by using seven criteria pollutants, PM2.5 PM10 CO NH3 NO2 SO2 and O3 parameters from March 20, 2020, to June 30, 2020. In doing so, we analyzed each pollutant's concentration before the announcement of a complete lockdown in Delhi and Mumbai and compared the aftermaths with before, during the lockdown period. The study also evaluates whether Delhi and Mumbai's air quality increases after the end of the lockdown. Our key findings will provide important information for Delhi and Mumbai's city administration to develop new rules and regulations to improve air quality.

Table 1.

Schedule of Covid-19 pandemic history in India.

| Phase | Start of Lockdown | End of Lockdown | Total Days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase-1 | 25 March 2020 | April 15, 2020 | 21 |

| Phase-2 | 15 April 2020 | 03 May 2020 | 19 |

| Phase-3 | 04 May 2020 | 17 May 2020 | 14 |

| Phase-4 | 18 May 2020 | 31 May 2020 | 14 |

Data source: https://www.india.gov.in/

2. Area of study

This study has focused on Delhi and Mumbai, as these are the most populous cities in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Delhi is the second-largest megacity of the world, with a population growth rate of 21 percent and having a population of over 16.78 million (Census, 2011; http://census2011.co.in). The National Capital Territory (NCT) Delhi located in Northern India and lies between N-latitude 28° 36′ 36″ and E-longitude 77° 13′ 48″ with an area of about 1484 km2 (700 km2 Urban and 783 km2 rural). Delhi has dual status as a state and city incorporating Shahdra Block, Najafgarh Block, Mehrauli Block, and Kanjhawla Block. Delhi features a dry winter, semi-arid climate, and weather can be categorized into five major seasons. Summer (Mar–May), Monsoon (Jun–Sept), short Post-monsoon (Oct–Nov), Winter (Dec–Feb), and Pre-monsoon (March–May). Temperature varies between 42 °C and 48 °C in summer and 4 °C to 10 °C in winter.

Mumbai is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is one of India's most populous cities and ranked the 17th most populous city globally (UN, 2018) with a population of over 20 million (Census, 2011; http://census2011.co.in). Mumbai lies between N-latitude 18° 58′ 30″ and E-longitude 72° 49′ 33″ with an area of about 603 km2. Geographically, Mumbai is located on a narrow peninsula on the southwest of Salsette Island, which lies between Vasai creek to the north, Thane Creek to the east, and the Arabian sea to the west. The weather of Mumbai is a tropical, dry, and wet climate that can be categorized into three seasons. Winter (Oct–Feb), Summer (Mar–May), and Monsoon (Jun–Sep). Temperature varies between 25 °C and 35 °C in summer and 18 °C–25 °C in winter.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Data specification

The study examines Delhi and Mumbai's air quality by using the data of numerous air quality observing units mounted there. The study retrieved the air quality information through thirty-six stations working in Delhi and nine stations mounted in Mumbai (Table 2 ). However, the study excluded the stations which have incomplete data. The observing organizations for these air quality measuring units are comprised of continuous ambient air quality monitoring (CAAQM) – CBCB, manual ambient air quality monitoring (MAAQM) – CPCB, Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) Pune, Delhi pollution control committee (DPCC), and System of Air Quality, Weather Forecasting And Research (SAFAR). The information regarding the 24-h concentration of major air pollutants, i.e., Carbon Monoxide (CO), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), Particulate Matters (PM10 and PM2.5), Ozone (O3), Ammonia (NH3), and Sulphur Dioxide (SO2), have been acquired from the database of Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB).

Table 2.

Air Quality monitoring stations in Delhi in Mumbai.

| Delhi stations | Mumbai stations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alipur | IHBAS | Okhla Phase-2 | Bandra |

| Dr. Karni Singh Shooting Range | Major Dhyan Chand National Stadium | Sri Aurobindo Marg | Chhatrapati Shivaji Intl. Airport (T2) |

| Ashok Vihar | Jahangirpuri | Punjabi Bagh | Colaba |

| Aya Nagar | Lodhi Road | Pusa | Kurla |

| Bawana | ITO | R K Puram | Powai |

| Burari Crossing | Mandir Marg | Rohini | Sion |

| CRRI Mathura Road | Mundka | Shadipur | Vasai West |

| DTU | NSIT Dwarka | Sirifort | Vile Parle West |

| Anand Vihar | Najafgarh | Sonia Vihar | Worli |

| Dwarka-Sector 8 | Narela | Patparganj | |

| East Arjun Nagar | Nehru Nagar | Vivek Vihar | |

| IGI Airport (T3) | North Campus | Wazirpur | |

Source. Central pollution control board (http://www.cpcb.nic.in/)

3.2. Estimation strategy

The Air Quality Index (AQI) is estimated based on a benchmark fixed for each pollutant. The impact of a specific pollutant is captured in a single index by utilizing the correct accretion method (Ott, 1978). Previously, the maximum sub-index technique was used to build the air quality index through five pollutants, i.e., PM10, CO, NO2, SO2, and PM2.5. Moreover, IITM introduced a new air quality index (IITM-AQI) that includes O3 (Beig et al., 2010). It measured the air quality based on a six-point scale, such as Severe, Very poor, Poor, Moderately polluted, Satisfactory, and good. Further, Indian National Air Quality Standards (INAQS) introduced twelve air pollutants, i.e., SO2, NO2, O3, NH3, CO, PM2.5, PM10, Arsenic (As), Benzo a Pyrene (BaP), Lead (Pb), Nickel (Ni), and Benzene (C6H6) to gauge the air quality in India. Out of these twelve air pollutants, four factors, such as C6H6, Ni, As, and BaP, are measured on an annual basis, while others are measured on a one, eight, and 24-h basis. In order to examine the impact of lockdown befallen due to COVID-19 on the environmental quality of Delhi and Mumbai, this study analyzes the seven pollutant factors, i.e., NO2, SO2, CO, O3, PM2.5, PM10, and NH3, individually and also as an integrated index. This investigation compares the fallouts during the lockdown era, before the lockdown period, and after the lockdown period. This investigation computed the National Air Quality Index (NAQI) for Delhi and Mumbai in two steps. First, this study computes each pollutant factor's sub-index by utilizing the information of various stations installed in Delhi and Mumbai. Second, this investigation combines each sub-index's values through mathematical function to form the NAQI for Delhi and Mumbai Additionally, to gauge the health impact of lockdown in Delhi and Mumbai, this investigation applied six category scale established by (CPCB, 2015), which is given in Table 3 .

Table 3.

NAQI categories and Health Effects.

| AQI categories | Health Effect |

|---|---|

| Good (0–50) | Minimal impact |

| Satisfactory (51–100) | Minor breathing discomfort to sensitive people. |

| Moderately polluted (101–200) | May cause breathing discomfort to people with lung disease |

| Poor (201–300) | May cause breathing discomfort to people on prolonged exposure, and discomfort to people with heart disease. |

| Very poor (301–400) | May cause respiratory illness to the people on prolonged exposure. Effect may be more pronounced in people with lung and heart diseases. |

| Severe (401–500) | May cause respiratory impact even on healthy people, and serious health impacts on people with lung/heart disease. |

Source. Central pollution control board (http://www.cpcb.nic.in/)

The sub-index for each pollutant is computed by employing 24 h mean data (8 h for Ozone and Carbon Monoxide) and pollutant concentration breakpoints displayed in Table 4 (CPCB, 2015). We develop the sub-index by following the model of (CPCB, 2015). The equation for the sub-index is given below,

| (1) |

Here I i indicates sub-index for pollutant parameter i, while defines the value of pollutant concentration at time t. Furthermore, and specified the pollutant factor breakpoint, which is and, respectively. As well, and nominate the pollutant factor breakpoint corresponding to and, respectively. The accumulation of these indices to achieve the NAQI is performed through mathematical summation, weighted additive form, root mean square from, weighted additive form, maximum or minimum operator, or multiplication as follows (Mahato et al., 2020);

Table 4.

AQI and pollutant concentration breakpoints.

| AQI | NO2 (24hr) μg/m3 |

NH3 (24hr) μg/m3 |

CO (8hr) mg/m3 | SO2 (24hr) μg/m3 |

PM10 (24hr) μg/m3 |

PM2.5 (24hr) μg/m3 |

O3 (8hr) μg/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–50 | 0–40 | 0–200 | 0–1.0 | 0–40 | 0–50 | 0–30 | 0–50 |

| 51–100 | 41–80 | 201–400 | 1.1–2.0 | 41–80 | 51–100 | 31–60 | 51–100 |

| 101–200 | 81–180 | 401–800 | 2.1–10 | 81–380 | 101–250 | 61–90 | 101–168 |

| 201–300 | 181–280 | 801–1200 | 10–17 | 381–800 | 251–350 | 91–120 | 169–208 |

| 301–400 | 281–400 | 1200–1800 | 17–34 | 801–1600 | 351–430 | 121–250 | 209–748 |

| 401–500 | 400+ | 1800+ | 34+ | 1600+ | 430+ | 250+ | 748+ |

Source. Central pollution control board (http://www.cpcb.nic.in/)

Weighted additive form;

| (2) |

where w indicates the weight of the pollutant factor, and I denote the sub-index for pollutant factor i. while n represents the number of variables utilized in this investigation. The investigation assigns equal weight to these indices, inferring that.

Non-linear aggregated method;

| (3) |

Here h represents the positive number > 1.

Root-mean-square method;

| (4) |

Minimum or maximum operator method (Ott, 1978);

| (5) |

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Spatial analysis of each pollutant before, during, and after the lockdown period

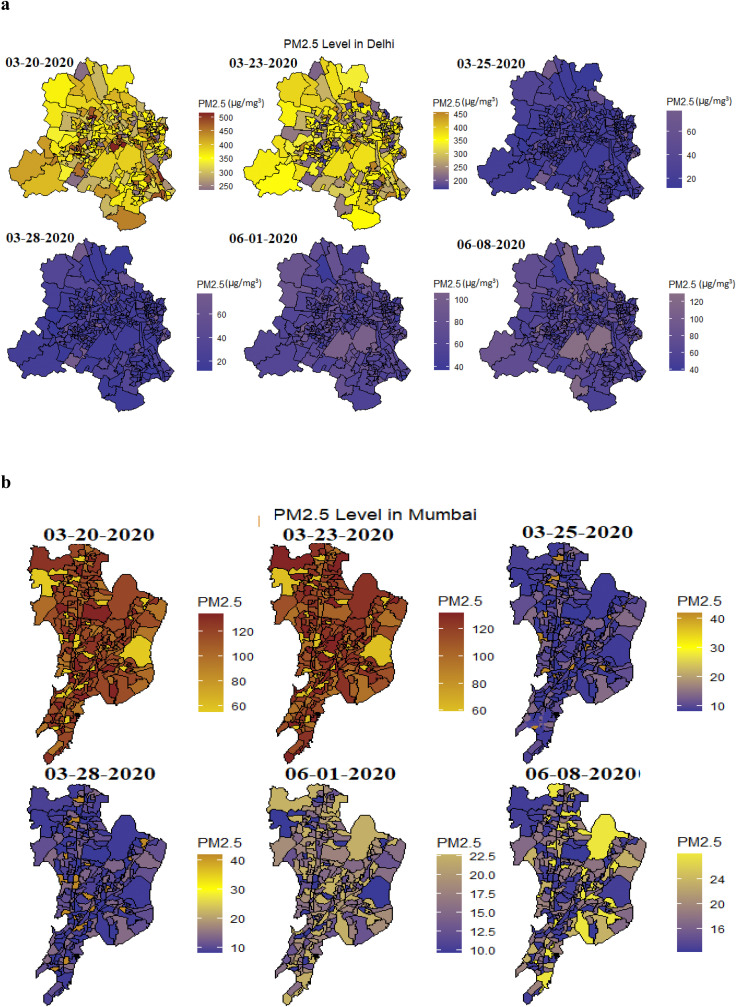

To curb the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of India imposed a strict nation-wise lockdown in the last week of March, which limited the citizens' movement and social interaction. As a result of the lockdown, traffic movement reduced significantly, and all the commercial activities were suspended, which affected the people's daily life. On the other hand, dramatic improvements in air quality have been observed, especially in primary dominated air quality, such as PM2.5 level in Delhi (Fig. 1 a). Before the lockdown on 20 and 23 March, the PM2.5 level ranges from 200 μg/m3 to 500 μg/m3 in different Delhi areas. The Indian government announced a phase one lockdown from March 24, 2020, to April 15, 2020, for 21 days. Just after the one day of lockdown, the PM2.5 level reduced 20 μgm/m3 in most areas of Delhi. The government lifts the lockdown on May 31, and the PM2.5 level remained between the range of 20 μg/m3 to 120 μg/m3 on June 01, 2020, and June 06, 2020, in Delhi (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the PM2.5 level in Mumbai before lockdown range between 60 μg/m3 to 120 μg/m3, which is lower as compare to Delhi PM10 (Fig. 1b). Just after the one day of the lockdown, the PM2.5 level declines between 10 μg/m3 to 40 μg/m3 in various wards of Mumbai. Mumbai shows a consistent improvement in the PM2.5 level even after the government lifts the lockdown on May 31. The PM2.5 values range from 10 μg/m3 to 24 μg/m3 in June, inferring that lockdown has a substantial long-term impact on reducing air pollution in Mumbai.

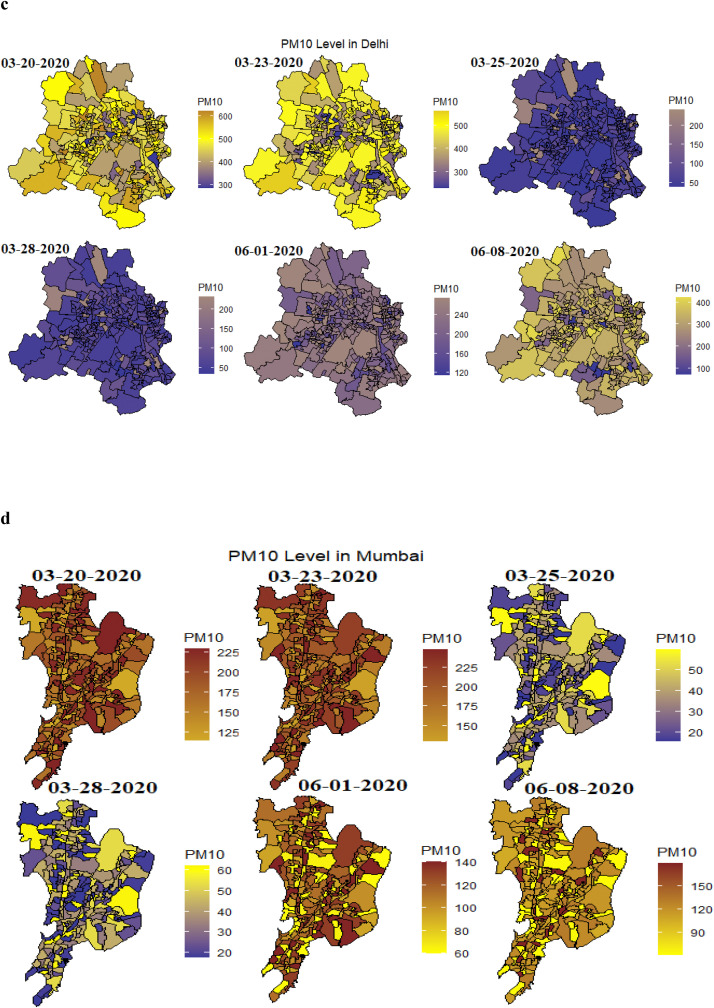

Fig. 1.

Spatial investigation of PM2.5, PM10, CO, and NO2 in NCT Delhi and Mumbai.

A similar pattern is shown by PM10 in Delhi up to 600 μg/m3 before lockdown (Fig. 1c). Just after two days of lockdown, it drops down to 200 μg/m3. Similarly, in Mumbai, the PM10 value before lockdown is 225 μg/m3, but it drops down to 60 μg/m3 after four days of lockdown (Fig. 1d). A slight increase is seen in Delhi up to 400 μg/m3 and 150 μg/m3 in Mumbai in June after lockdown (Fig. 1c and d). The most important dissimilarity is noticeable in PM2.5 and PM10. It can be seen clearly from the spatial concentration pattern of these two contaminants during the lockout time on different days. Road traffic is the principal cause of PM2.5 and PM10 in the megacities Delhi and Mumbai. Other causes include industrial production, building works, and the re-suspension of dust. Notably, the concentrations of these two pollutants decreased below the permitted limit after one day of lockdown (March 23 to March 25). These corresponding numbers of PM2.5 and PM10 are based on geographic locations. Hence, a minor cessation of lockdown measures for the required vehicles and localized industries outside the hot spots, i.e., COVID-19 contaminated area, has increased PM10 and PM2.5 concentration on June 01 and June 08 (post lockdown). Mumbai shows more improvement in PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations after lockdown compared to NCT Delhi.

Other essential contaminants except PM10 and PM2.5 are CO and NO2, which also shows a substantial decline during the lockdown era in Delhi (Fig. 1e and g). The CO level in Delhi varies from 2 μgm/m3 to 6 μgm/m3 in the pre-lockdown era and drops down to 0.5 μg/m3 to 2.5 μg/m3 during the lockdown era and remains consistent even after the expiry of lockdown in June (Fig. 1e). A similar pattern was seen in the NO2 emissions in Delhi as its concentration lies between 50 μgm/m3 to 150 μgm/m3 before lockdown. Tough, during, and post-lockdown, it remains between 20 μg/m3 to 60 μg/m3 (Fig. 1g). The CO emissions in Mumbai are lower than Delhi before lockdown, ranges from 1 mg/m3 to 3 mg/m3. After lockdown, it reduced up to 0.25 mg/m3 to 0.80 mg/m3 and remains persistent in the post-lockdown period (Fig. 1f). NO2 level in Mumbai lies between 30 μg/m3 to 100 μg/m3 in the pre-lockdown period, but after two days of lockdown on March 25, it drops up to 10 μg/m3. In the post-lockdown period in June 2020, it slightly goes up to 30 μg/m3 (Fig. 1h), which is lower than NCT Delhi in the same period. In urban areas, CO and NO2 pollutants are generated primarily from the activity of road traffic combustion, particularly petrol and, to a lesser degree, gasoline, cars, industrial production, and coal plants. All these industries closed their activities during this lockout period. Consequently, it resulted in a decrease in contaminants, such as CO and NO2.

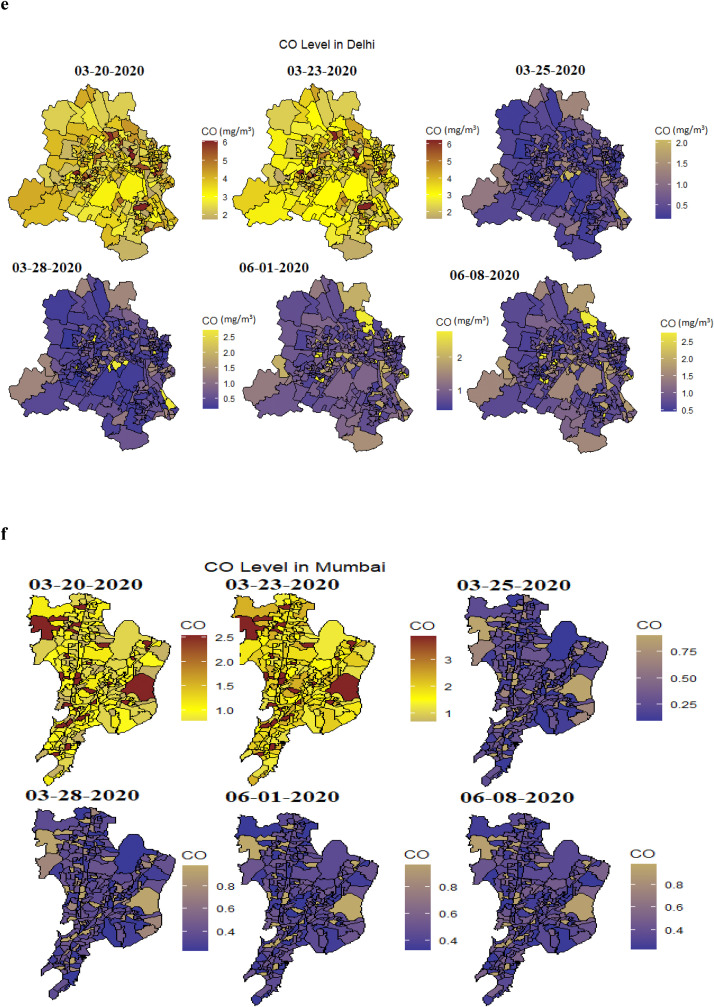

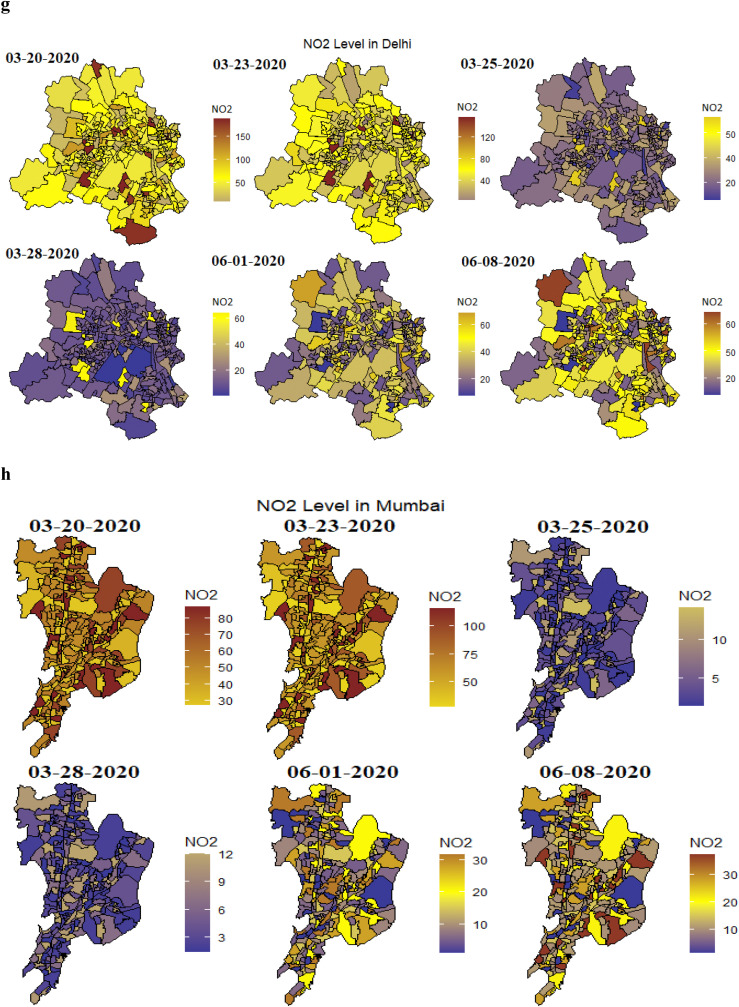

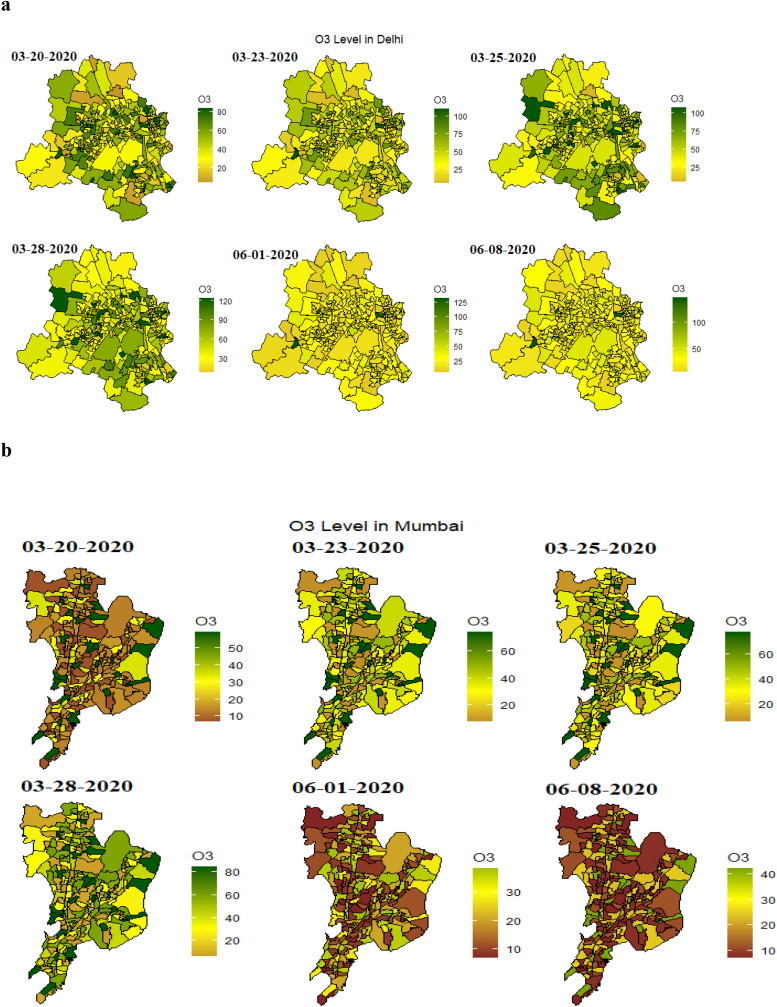

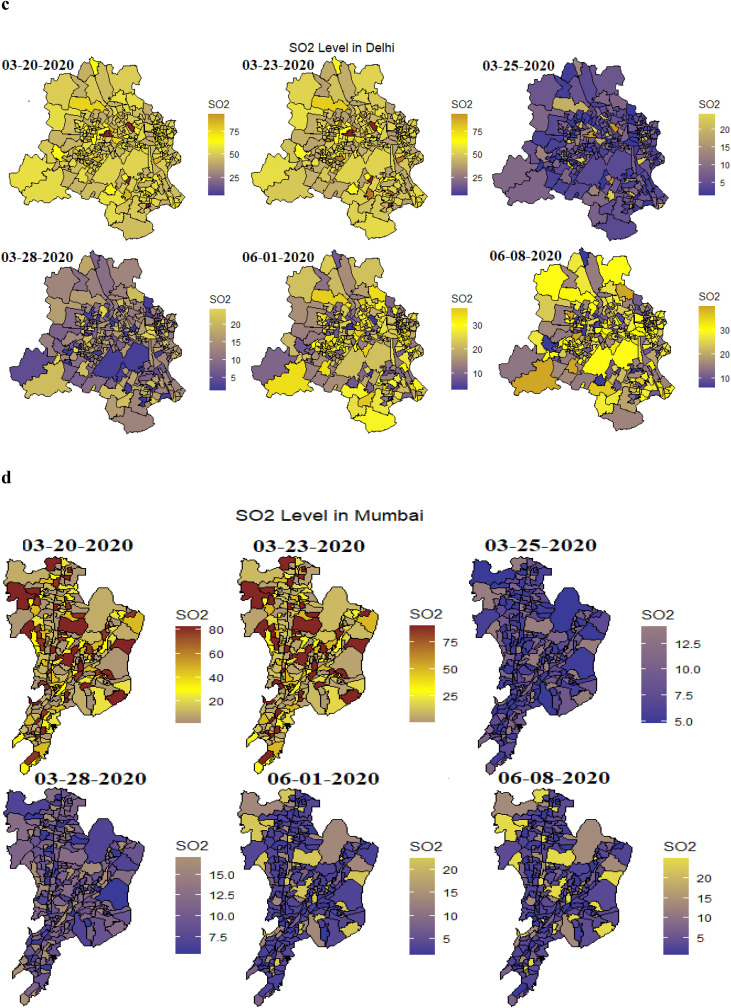

Subsequently, concentration levels of O3 in the megacity of Delhi increases significantly from 100 μg/m3 to 120 μg/m3 after three days of lockdown due to three possible collective causes (Fig. 2 a). First, lowering NO in the lockdown will cause urban O3 to bump up, as opposed to actions in rural areas where the concentration of NO is largely restricted (Monks et al., 2015). Second, the depletion of nitrogen oxide (NO) decreases the usage of O3 (titration, NO + O3 = NO2 + O2), contributing to a rise in O3 concentrations. Third, The inevitable increase of temperatures and insolation in the northern hemisphere from March to August as a result of sun movement to the north leads to an increase in O3, when the maximum O3 is usually recorded (Gorai et al., 2017). Further, O3 slightly increases in Mumbai and again drops down to 40 μg/m3 level after in the post-lockdown period (Fig. 2b). Mumbai is the fourth most populous city in the world and one of the world's most populous metropolitan areas. Because of Delhi's offshore position outside the sea, it is a low SO2 city as most of this pollutant originates from maritime traffic (large cargo ships, cruise ships, and ferries). SO2 level in Delhi ranges from 25 μg/m3 to 75 μg/m3 in the pre-lockdown period; while it considerably decreases up to 20 μg/m3 after two days of lockdown and remains at 30 μg/m3 levels in the post-lockdown age (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Spatial investigation of SO2, NH3, and O3, in Delhi and Mumbai.

The concentration of SO2 in Delhi usually remains below the permissible level, and the concentration of SO2 during this lockdown time has experienced a decrease compared with the pre-lockdown epoch. Due to the lockdown situation similar pattern was seen in Mumbai, as shown in (Fig. 2d). On the other hand, NH3 is marginally decreased in Delhi from 75 μg/m3 in pre-lockdown to 60 μg/m3 during the lockdown period and again goes up to 100 μg/m3 in the post-lockdown period (Fig. 2e). Though in Mumbai, it shows a significant decrease during the lockdown period 6 μg/m3 and again goes up to 75 μg/m3 in post lockdown (Fig. 2f). The fact that NH3 is derived from fields other than agriculture is marginal and widely accepted (Sutton et al., 1995). Consequently, the NH3 concentration often falls below the appropriate level in Mumbai. Because petrol engine vehicles are a leading cause of urban NH3, substantial decreases in NH3 concentrations during the lockdown period were documented (Kean et al., 2000).

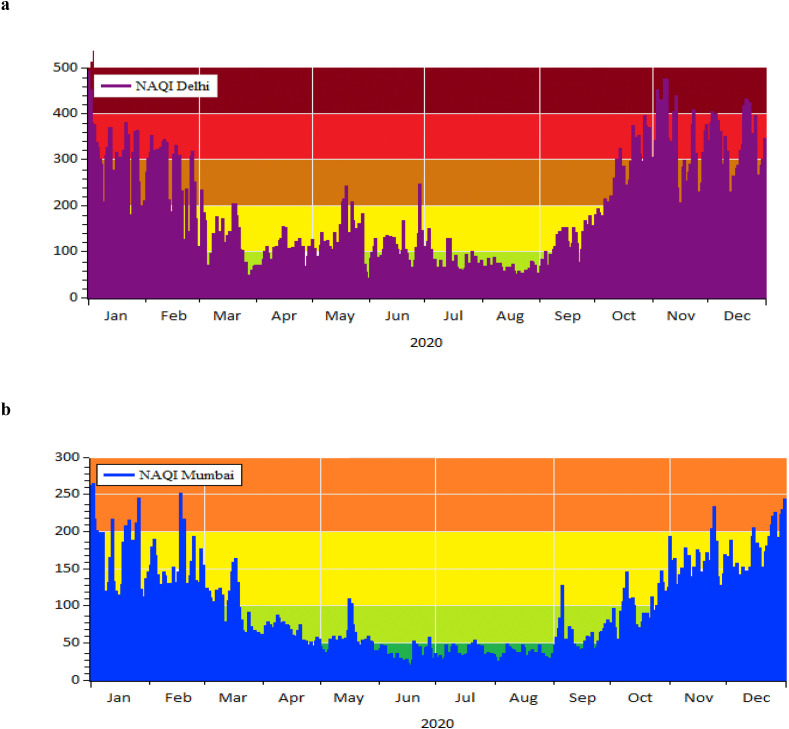

4.2. Changes in pollutants from the pre-lockdown period to after lockdown period

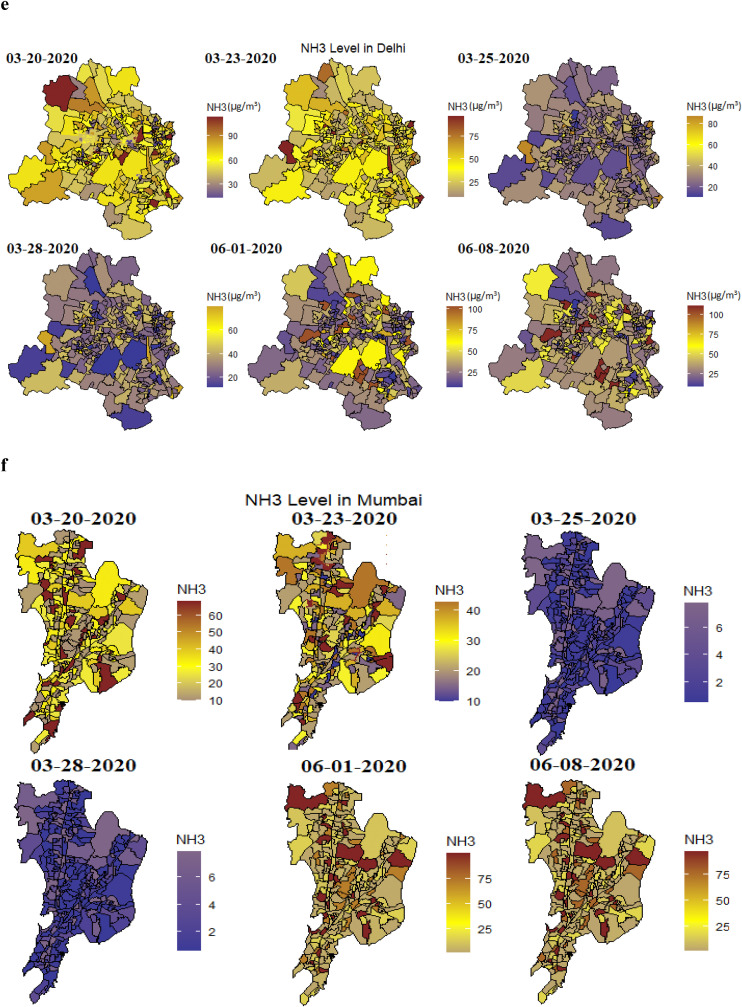

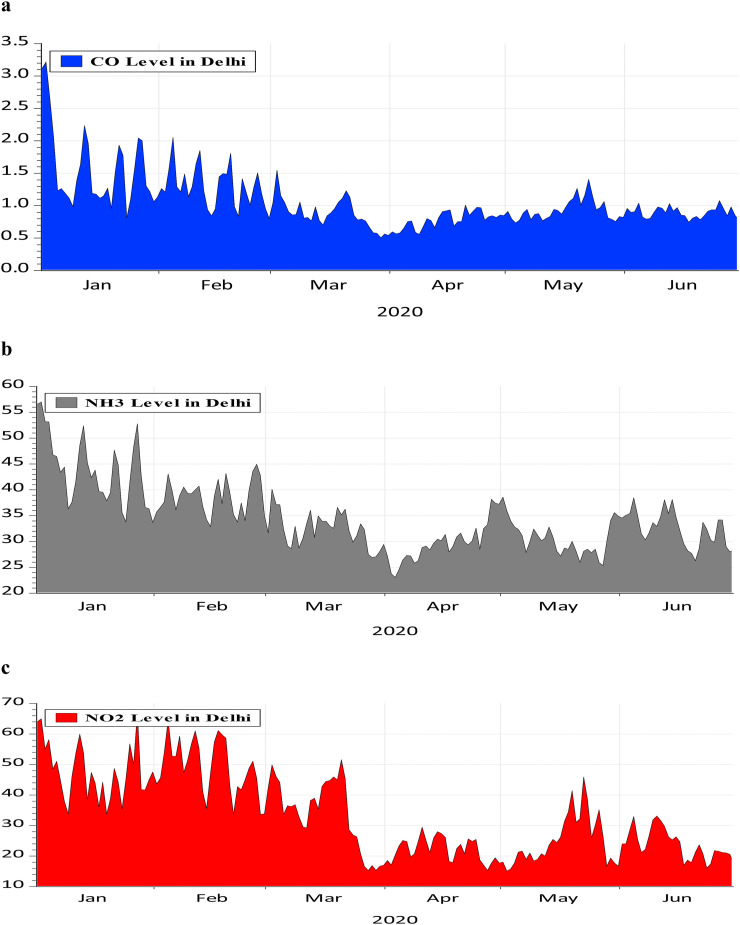

During the lockdown, a significant reduction in air pollutants has been observed in the megacities of India, Delhi, and Mumbai (see Fig. 3, Fig. 4 ). These figures show the variations before, during, and after the lockdown period in each pollutant. In particular, concentrations of CO, NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 showed substantial declines during the lockdown era in both cities.

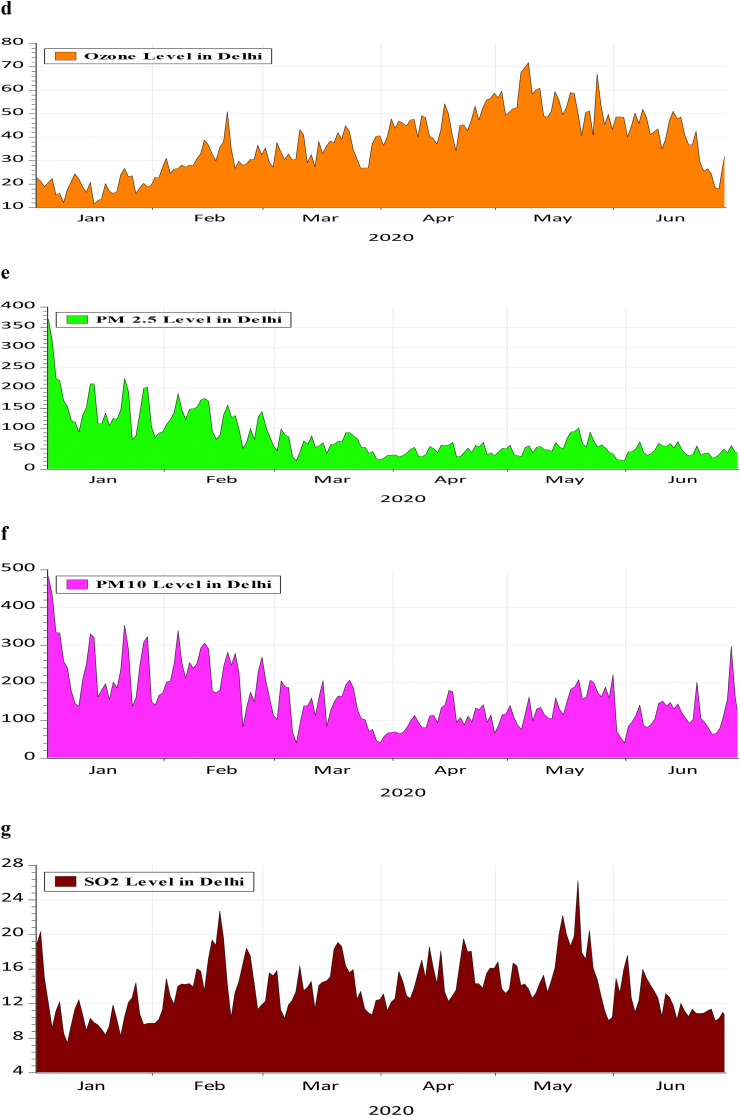

Fig. 3.

Variations in PM2.5, PM10, CO, O3, NO2, SO2, and NH3 in Delhi.

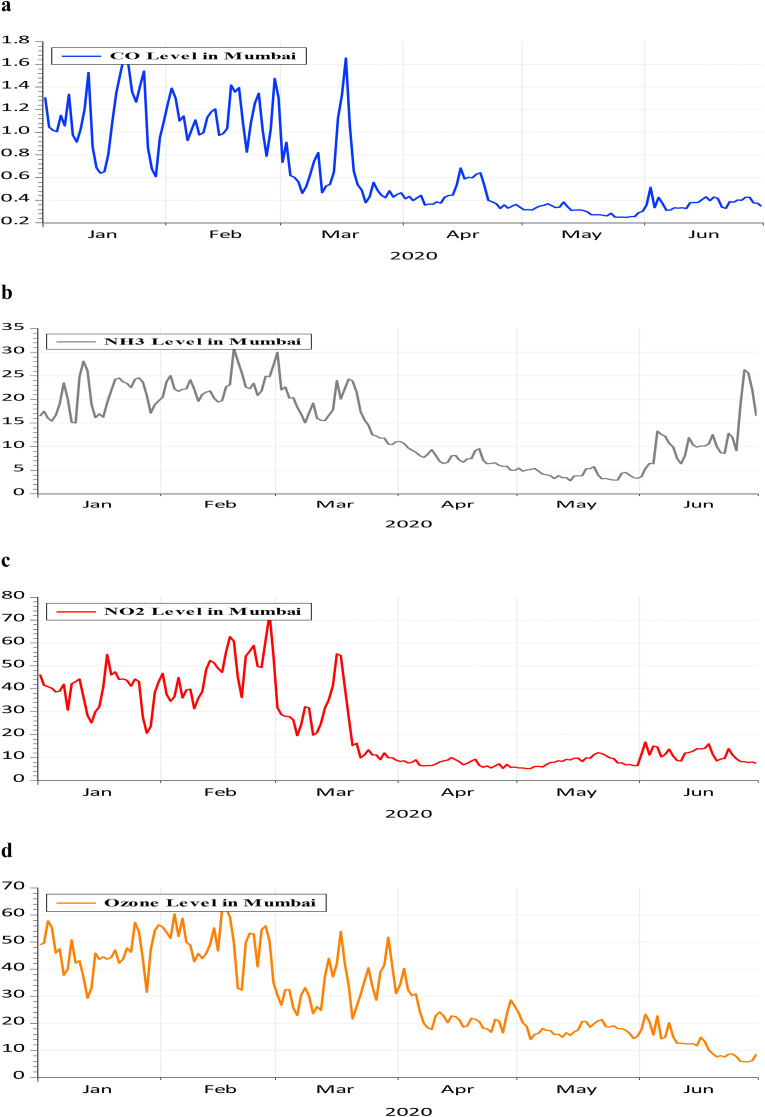

Fig. 4.

Variations in PM2.5, PM10, CO, O3, NO2, SO2, and NH3 in Mumbai.

PM2.5 concentrations have decreased from 200 μg/m3 to 50 μg/m3 in Delhi (Fig. 3e); it remains lower till June due to lockdown in effect. Similarly, the value of PM2.5 in Mumbai remains under 100 μg/m3 from January to March, but during the lockdown period, it fell to permissible levels of 20 μg/m3 until June 30, 2020 (Fig. 4e). In the same way, the average PM10 level in Delhi is 300 μg/m3 from January 2020 to March 2020; as the Indian government announced lockdown in late March, its value fells down to 100 μg/m3 and goes up at the end of June (post lockdown period) (Fig. 3f). The average PM10 concentration in Mumbai remains up to 200 μg/m3 from January to March. However, during the lockdown, it reduced up to 40 μg/m3 level at the end of June 2020 (Fig. 4f). The rate of change between these pollutants is higher in Delhi compared to Mumbai.

Other contaminants that display substantial differences between pre and during lockdown are CO and NO2 in Delhi and Mumbai. The CO emissions in Delhi in the pre-lockdown period from January 2020 to March 2020 shows 1.5 μg/m3, but during the lockdown, its value fell up to 0.5 μg/m3 and again increases up to 1 μg/m3 in post lockdown period (Fig. 3a). Whereas in (Fig. 4a) the CO level in Mumbai is 1.4 mg/m3 in the pre-lockdown period and falls up to 0.4 μg/m3 during the lockdown period. The NO2 level in Delhi and Mumbai remains 50 μg/m3 in the pre-lockdown age. Nevertheless, during the lockdown in Delhi, NO2 remains up to 20 μg/m3 and again increases in the post-lockdown era (Fig. 3c). NO2 level drops to 10 μg/m3 during the lockdown and slightly upsurge after lockdown (Fig. 4c). However, the decrease in SO2 in Delhi and Mumbai were lower compared to the other pollutants (Fig. 3, Fig. 4g). Furthermore, NH3 was decreased during the lockdown phase in Delhi and Mumbai compared to the pre-lockdown period. However, its level goes up in the post-lockdown phase as expected because economic activities are resuming (Fig. 3, Fig. 4b). Besides, an 8 h average daily O3 concentration indicates a rise with an upward trend n Delhi (Fig. 3d), while in Mumbai, it showed a downward trend (Fig. 4d). In this case, it is quite feasible to consider that from April to August is the high O3 duration in the Indian Subcontinent due to an escalation in insolation (Gorai et al., 2017). The cause of the rise in the concentration of O3 is a reduction in nitrogen oxide (NO).

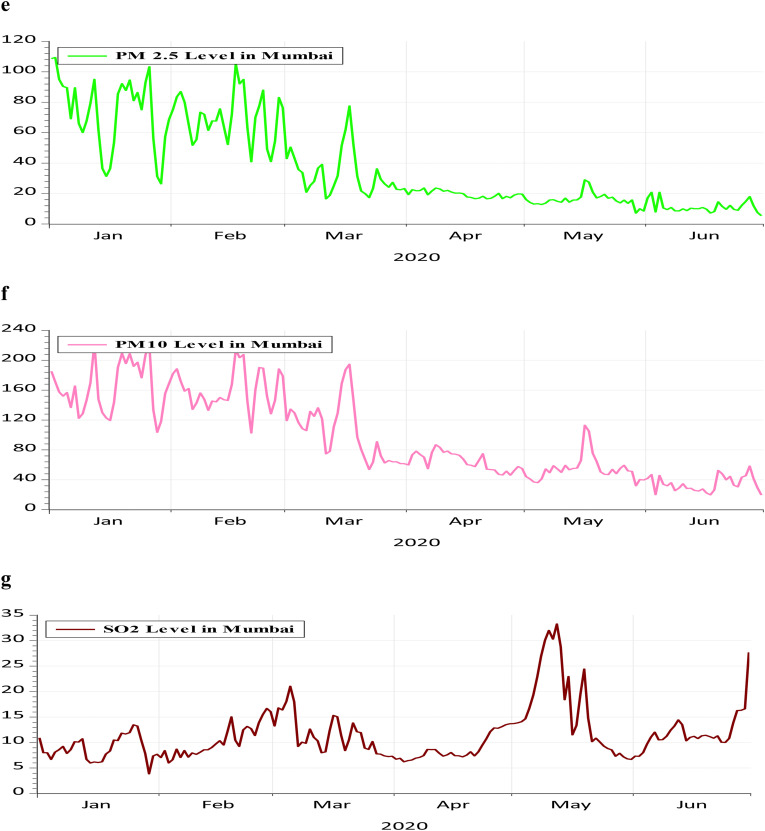

4.3. Dissimilarities in NAQI of Delhi and Mumbai through January 01, 2020, to December 31, 2020

Fig. 5a and b exhibited the National Air Quality Index (NAQI) in Delhi and Mumbai, respectively. The absolute improvement in air quality can be seen in both cities of India during the lockdown era. In Delhi, during the pre-lockdown period (January 2020–March 22, 2020), the NAQI remains between the “Poor” to the “Severe” health category. However, as the lockdown transpired in Delhi due to COVID-19 on March 23, 2020, NAQI suddenly fells in the range of the “GOOD” health category. During phase one of lockdown, NAQI lies amid 50 to 150, which represents the good to the moderate category of health index. Hence, the air quality has improved in Delhi during the lockdown era. On the other hand, Mumbai shows more improvement concerning NAQI as its pre lockdown air quality lies among “Moderately polluted” to “Poor” health index (101–250). However, during and after the lockdown period, it remains consistent below 100 points at the “Satisfactory” level (Fig. 5b). It implies that megacities of the world can improve the air quality by strict management practices. However, the smart lockdown to limit human activities may be the other choice to reduce air pollution, significantly reducing the air pollutants and improving environmental quality (Bherwani et al., 2020). Moreover, after the lockdown period (August 31, 2020, to December 31, 2020), NAQI progressively increases in both cities and imperatively achieved its position before the lockdown era, inferring that lockdown does not have a long term effect on air quality.

Fig. 5.

National air quality index (NAQI) for Delhi and Mumbai.

4.4. 70 days examination of each pollutant during and after lockdown era

Table 5, Table 6 show the 70 days analysis of change in each pollutant before and during the lockdown in Delhi and Mumbai, respectively. In particular, concentrations of CO, NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 showed substantial declines during the lockdown in both cities. Before lockdown, the PM2.5 in Delhi was 107.75 μg/m3, but during the lockdown, it drops to 49.37 μg/m3. Similarly, the PM2.5 has 58.30 μg/m3 value in the pre-lockdown era, and after lockdown, it declines to 18.80 μg/m3. Thus, 70 days of average PM2.5 concentrations have decreased by 54.17% in Delhi and 67.75% in Mumbai. PM10 concentrations have a net change of −79.45 in Delhi and −88.67 in Mumbai. Other contaminants that display substantial differences before and during lockdown are CO -31.61% in Delhi and −61.58% in Mumbai. The percentage change in CO emission in Mumbai is more convincing than in Delhi. NO2 emission has a net change of −22.25 μg/m3 and -31.19 μg/m3 in Delhi and Mumbai, respectively, inferring that there was an imperative decrease in these parameters due to lockdown. However, the reduction in SO2 in Delhi was 11.87%, and in Mumbai, it revealed a decline of 14.46%. However, NH3 documented a net change of −7.85 and −14.86 in Delhi and Mumbai during the lockdown era, respectively. The 8hrs average daily O3 concentration disclosed substantial growth of 66.46% in Delhi during the lockdown era than the pre-lockdown period of 70 days. Nevertheless, O3 concentration decreased by 47.27 during 70 days of lockdown compared to 70 days of pre-lockdown in Mumbai. These outcomes indicated that lockdown has brought a drastic decrease in emissions levels and dramatically improve air quality.

Table 5.

70 days of analysis before and during the lockdown in Delhi.

| Variable | Before Lockdown | During Lockdown | Net change | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 1.221 | 0.835 | −0.386 | −31.611 |

| NH3 | 37.933 | 30.076 | −7.857 | −20.712 |

| NO2 | 45.287 | 23.033 | −22.254 | −49.139 |

| Ozone | 29.049 | 48.356 | 19.307 | 66.463 |

| PM2.5 | 107.758 | 49.376 | −58.382 | −54.179 |

| PM10 | 197.066 | 117.608 | −79.459 | −40.321 |

| SO2 | 13.495 | 15.098 | 1.603 | 11.879 |

Source: Author's calculation

Table 6.

70 days of analysis before and during the lockdown in Mumbai.

| Variable | Before Lockdown | During Lockdown | Net change | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 0.997 | 0.383 | −0.614 | −61.583 |

| NH3 | 21.511 | 6.645 | −14.866 | −69.110 |

| NO2 | 39.309 | 8.111 | −31.199 | −79.367 |

| Ozone | 43.048 | 22.703 | −20.346 | −47.262 |

| PM2.5 | 58.310 | 18.802 | −39.508 | −67.755 |

| PM10 | 149.163 | 60.489 | −88.674 | −59.447 |

| SO2 | 10.665 | 12.207 | 1.542 | 14.463 |

Source: Author's calculation

4.5. Understanding the pattern of major pollutants concentration over the last two years

To complement the major findings as illustrated in the previous sub-sections, we have investigated the entire lockdown era (i.e., March 25, 2020, to May 31, 2020) and compared the findings of this period with the same previous period in 2018 and 2019. Table 7 highlights the fallouts of year-wise mean variations in each pollutant from March 25, 2020, to May 31, 2020, in contrast with the previous two years, i.e., 2018 and 2019, for the same period. The findings stated that PM2.5 concentration has dramatically reduced by 37.5% and 20.6% during the lockdown period in comparison with the same period in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Moreover, PM10 concentration disclosed a 50.31% decline equated to 2019 over the same period. Additionally, NH3, NO2, SO2, and CO encountered 20.60%, 53.35%, 41.02%, and 36.54% deterioration in their concentrations compared with 2019 over the same period, respectively. Air pollution has significantly reduced due to limited transportation and industrial activities during lockdown days (P. Wang et al., 2020). A few days after the lockout, some of the air pollutants reached the World Health Organization (WHO) standards (Jordan, 2020). Nevertheless, again, the findings indicated that lockdown implementation could lead to a significant increase in air quality, which should be introduced as an additional pollution reduction tool.

Table 7.

Year-wise analysis of each pollutant from 25 March to 31 May.

| Variable | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | % change (2018) | % change (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3 | 42.893 | 33.759 | 26.802 | −37.514 | −20.608 |

| NO2 | 49.542 | 49.711 | 23.187 | −53.197 | −53.357 |

| PM2.5 | 89.688 | 85.383 | 49.205 | −45.137 | −42.371 |

| PM10 | 251.103 | 237.452 | 117.986 | −53.013 | −50.312 |

| Ozone | 51.577 | 47.510 | 48.638 | −5.699 | 2.376 |

| SO2 | 13.744 | 20.479 | 12.077 | −12.134 | −41.029 |

| CO | 1.4368 | 1.3493 | 0.856 | −40.409 | −36.543 |

Source: Author's calculation

5. Conclusion

Air pollution has become the principal problem people are encountering on the earth. However, a recent lockdown that has befallen due to the COVID-19 disease imperatively improves global air quality. This behavior allows us to analyze the air quality in the two most populated cities globally, i.e., Delhi and Mumbai. The study examined the influence of lockdown on PM2.5, PM10, NH3, CO, O3, and SO2 before, during, and after the lockdown era. First, the study analyzes these pollutants through a spatial approach; second, the study builds the National Air Quality Index (NAQI) in NCT Delhi and Mumbai. The findings revealed that two days before the lockdown, PM2.5 concentration remains between the 200 μgm/m3 to 500 μgm/m3 in Delhi. However, as the lockdown was announced in Delhi, it decreased to 20 μgm/m3 in most NCT Delhi areas. Similarly, the PM2.5 level in Mumbai before lockdown range between 60 μgm/m3 to 120 μgm/m3, and on the second day of lockdown, it diminishes between 10 μgm/m3 to 40 μgm/m3 in various wards of Mumbai. Moreover, PM10 concentration before lockdown remains 225 μg/m3, but it fell to 60 μg/m3 as a lockdown announced in Mumbai. Further, NO2 emissions in Delhi stay between 50 μgm/m3 to 150 μgm/m3 before lockdown. Although, during and post-lockdown remains amongst 20 μg/m3 to 60 μg/m3. Conversely, NH3 emission was reduced in Delhi from 75 μg/m3 to 60 μg/m3 after two days of lockdown. The findings revealed that CO emissions from January 2020 to March 23, 2020, showed the level of 1.5 mg/m3, but during the lockdown in Delhi, its value fell to 0.5 mg/m3 and again rise to 1 mg/m3 in post lockdown period. However, Mumbai's carbon monoxide emission was 1.4 mg/m3 in the pre-lockdown period and compacted up to 0.4 mg/m3 during the lockdown period. The Ozone concentration in Delhi has increased by 2.37% during the lockdown period in comparison with 2019 over the same period, i.e., March 23, 2019, to May 31, 2019. The inspection documented that NAQI in Delhi varies from 201 to 480, representing the poor to severe health index. However, during the lockdown period, NAQI in Delhi decreased to a good category of health index. However, after the lockdown, the AQI index in Delhi gradually increased from satisfactory to severe health index. Likewise, NAQI in Mumbai remains between a good and satisfactory level of health index during the lockdown, but after the lockdown, it changes from satisfactory to poor health index. Hence, the study confirmed that lockdown does not pose a long-term effect on the air quality in Delhi and Mumbai.

Based on the results, this study offers the following policy recommendations. First, the government should design a proactive strategy to reduce air pollution levels. Second, the government should implement a regional long-term joint-emissions control plan to improve environmental quality rather than sporadic and abrupt interventions. Third, we emphasize the Indian government to minimize fossil fuel consumption in vehicles and manufacturing industries to mitigate air pollution, which helps improves the air quality in megacities.

Credit author statement

Khurram Shehzad: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Revision; Liu Xiaoxing: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; Mahmood Ahmad: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Revision; Abdul Majeed: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Farheen Tariq: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing; Salman Wahab: Writing – review & editing

Funding

The study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71673043).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Baldasano J.M. COVID-19 lockdown effects on air quality by NO2 in the cities of Barcelona and Madrid (Spain) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741:140353. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao R., Zhang A. Does lockdown reduce air pollution? Evidence from 44 cities in northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;731:139052. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beig G., Ghude S.D., Deshpande A. Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology; 2010. Scientific Evaluation of Air Quality Standards and Defining Air Quality Index for India.https://www.tropmet.res.in/~lip/Publication/RR-pdf/RR-127.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Nair M., Musugu K., Gautam S., Gupta A., Kapley A., Kumar R. Valuation of air pollution externalities: comparative assessment of economic damage and emission reduction under COVID-19 lockdown. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 2020;13:683–694. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00845-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondet I., Schreck E., Viers J., Casas S., Jubany I., Bahí N., Zouiten C., Dufréchou G., Freydier R., Galy-Lacaux C., Martínez-Martínez S., Faz A., Soriano-Disla M., Acosta J.A., Darrozes J. Atmospheric dust characterisation in the mining district of Cartagena-La Unión, Spain: air quality and health risks assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;693:133496. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138882. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas G., Siciliano B., França B.B., da Silva C.M., Arbilla G. The impact of COVID-19 partial lockdown on the air quality of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139085. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorai A.K., Tchounwou P.B., Mitra G. Spatial variation of ground level ozone concentrations and its health impacts in an urban area in India. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017;17:951–964. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2016.08.0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kean A.J., Harley R.A., Littlejohn D., Kendall G.R. On-road measurement of ammonia and other motor vehicle exhaust emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000;34:3535–3539. doi: 10.1021/es991451q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo E.J., Lantos J.D. Lessons learned from the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1323–1325. doi: 10.1111/apa.15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnon M. Mac, Zhu S., Carreras-Sospedra M., Soukup J.V., Dabdub D., Samuelsen G.S., Brouwer J. Considering future regional air quality impacts of the transportation sector. Energy Pol. 2019;124:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Li Y., An D., Han Y., Xu S., Lu Z., Crittenden J. Mining of the association rules between industrialization level and air quality to inform high-quality development in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;246:564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C.-J., Kang G.-U. Air quality variation in wuhan, daegu, and tokyo during the explosive outbreak of COVID-19 and its health effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:4119. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahato S., Pal S., Ghosh K.G. Effect of lockdown amid COVID-19 pandemic on air quality of the megacity Delhi, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730:139086. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlier M.E., Jina A.S., Kinney P.L., DeFries R.S. Extreme air pollution in global megacities. Curr. Clim. Chang. Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40641-016-0032-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monks P.S., Archibald A.T., Colette A., Cooper O., Coyle M., Derwent R., Fowler D., Granier C., Law K.S., Mills G.E., Stevenson D.S., Tarasova O., Thouret V., Von Schneidemesser E., Sommariva R., Wild O., Williams M.L. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015 doi: 10.5194/acp-15-8889-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ott W.R. Environmental indices: theory and practice. Environ. indices theory Pract. 1978;14:1453–1454. doi: 10.1016/0004-6981(80)90167-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pata U.K. How is COVID-19 affecting environmental pollution in US cities? Evidence from asymmetric Fourier causality test. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00877-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz M., Shehzad K. 2020. Gauging the Air Quality of New York: a Non-linear Nexus between COVID-19 and Nitrogen Dioxide Emission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad K., Sarfraz M., Ghulam S., Shah M. The impact of COVID-19 as a necessary evil on air pollution in India. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266:115080. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M.A., Place C.J., Eager M., Fowler D., Smith R.I. Assessment of the magnitude of ammonia emissions in the United Kingdom. Atmos. Environ. 1995;29:1393–1411. doi: 10.1016/1352-2310(95)00035-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN . 2018. The World's Cities in 2018.https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Chen K., Zhu S., Wang Peng, Zhang H. Severe air pollution events not avoided by reduced anthropogenic activities during COVID-19 outbreak. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;158:104814. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200801-covid-19-sitrep-194.pdf?sfvrsn=401287f3_2 [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Health Effects Institute, The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of British Columbia; Boston: 2018. State of Global Air: A Special Report on Global Exposure to Air Pollution and its Disease Brden. covid-19-sitrep-194.pdf?sfvrsn=401287f3_2. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2014. 7 Million Premature Deaths Annually Linked to Air Pollution.https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/air-pollution/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Shi B., Zheng Y., Shi Y., Xia G. Urban form and air pollution disperse: key indexes and mitigation strategies. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;57:101955. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Liu W. Does air pollution affect public health and health inequality? Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;203:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]