Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Musical murmurs (MMs), sometimes called seagull cry, goose cry, honks, or cooing murmur, are murmurs with a single frequency that sounds like a musical tone. Doppler detections usually show mirror-image parallel strings or bands of low to moderate frequency. Musical murmurs are mostly described in cardiac murmurs and have seldom been mentioned in cerebrovascular disease.

METHODS: A retrospective review of 12,000 patients from our neurosonographic data base of the past 7 years was conducted to find patients who had MMs during color-coded carotid and transcranial duplex sonographies.

RESULTS: Sixty-six musical murmurs were found in 60 patients (0.5% of all studied patients). There were 44 men and 16 women with a mean age of 63.8 years. Musical murmurs may occur with or without simultaneous turbulent flows, or very close to a high-intensity frequency (with systolic spindles) turbulent flow. Musical murmurs are detected more frequently in intracranial vessels (94%) than in extracranial cervical arteries. The pathologic changes corresponding to the area of MMs were high-grade stenosis of the arteries (58 MMs), small arteries serving as collateral circulation (5 MMs), carotid cavernous sinus fistulas (2 MMs), and Moyamoya disease (1 MM). Fifty (88%) of 57 patients with stenotic arterial lesions had histories of cerebral infarction or transient ischemic attack, and 64% of the cerebrovascular events occurred on the side appropriate to the MMs.

CONCLUSIONS: The presence of MMs in color-coded carotid duplex and transcranial color-coded duplex sonography imply severe underlying vascular diseases that require prompt treatment. Further cerebral angiographic study is warranted to clarify the underlying pathology in patients with MMs.

Musical murmurs (MMs), also called seagull cry, goose cry, honks, or cooing murmur, are murmurs with a single frequency that sounds like a musical tone. Doppler detections usually show mirror-image parallel strings or bands of low to moderate frequency. MMs have been speculated to result from regular vibrations of a cardiac structure with or without turbulent flow, from a vortex shedding resulting from blood flowing past an obstruction, and also from oscillating structures and pressure fluctuations in intracranial cerebral arterial spasm.1–4 MMs are mostly described in cardiac murmurs and have seldom been mentioned in cerebrovascular disease.

When Aaslid et al5 first introduced the 2-MHz pulsed-wave transcranial Doppler to detect the intracranial cerebral blood flow through the temporal bone in 1982, a new era in the noninvasive study of intracranial cerebral hemodynamics began. Transcranial color-coded sonography (TCCS) provides direct sonographic images of the intracranial vessels and brain parenchyma, facilitating the availability and accuracy of the clinical diagnosis. Nowadays, a combination of color-coded carotid duplex (CCD) and TCCS has become an important screening method in patients with at-risk cerebrovascular disease in Taiwan.6 However, the special finding of musical murmurs detected during CCD and TCCS has not been well described previously. This work focuses on the clinical features and anatomic correlation in patients with MMs.

Subjects and Methods

From 1996 to 2003, 12,000 patients with suspected cerebrovascular disorders were referred to our neurosonographic laboratory for CCD and TCCS study. The sonography studies were performed either by physicians or well-trained sonographers. The results of sonographic study were interpreted soon after the examination by experienced physicians who specialize in stroke management. All the results of sonographic studies, including the B-mode and Doppler findings, were recorded in computerized data base files with organized image storage systems. A retrospective review of the data base was conducted by the authors, who were blinded to the angiographic results to screen out patients who had MMs during sonographic studies. We also reviewed the medical records and the neuroimaging studies of those patients with MMs.

The CCD study was performed with an Ultramark 9 system (ATL, Bethell, Wash) or an ATL HDI 3000 system that combines a 5- to 10-MHz linear transducer for B-mode scanning and a 6-MHz transducer for Doppler detection. The TCCS study was performed with the same system, combining a 2- to 3-MHz transducer for B-mode scanning and a 2-MHz transducer for Doppler detection. TCCs methodology is described elsewhere.6 MMs are defined as mirror-image strings or bands occurring with equal distance above and below the baseline in accordance with pulsation on the Doppler waveform and sounding like a musical tone. Snoring or voice sounds could be excluded because of their randomization of occurrence and inconsistence with the pulsation. Clinical data were collected from the medical charts, and included the clinical symptoms, signs, diagnosis, and risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. All the patients received a brain CT or MR imaging study and further cerebral angiography by digital subtraction angiography (DSA), MR angiography (MRA), or computed tomographic angiography (CTA).

Results

Sixty-six MMs were found in 60 patients (0.5% of total patients) during the 7-year study period. Of this group, 44 were men and 16 were women, with a mean age of 63.8 years (range, 15–87 years). MMs were detected extracranially by CCD in 4 patients and intracranially, by TCCS, in 56 patients. Five patients had 2 or more MMs at different areas. The distribution of MMs is summarized in Table 1. Three extracranial MMs were located at the proximal internal carotid artery (ICA) and 1 MM was located at the proximal vertebral artery (VA). Intracranial MMs were detected at various areas corresponding to the sonographic anatomic locations of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) (14), middle cerebral artery (MCA) (21), and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) (13) and the terminal ICA (2), through temporal windows. Nine MMs were detected at areas corresponding to intracranial vertebrobasilar arteries through foraminal windows. Three MMs were detected at retro-orbital areas through orbital windows. Figure 1 shows different patterns of MMs detected by CCD and TCCS. On color-coded B-mode images, all the areas with MMs showed a heterogenous hyperechoic color flash, which was detected either within a segment of the artery or without adjacent color arterial flow. Markedly elevated turbulent flow with a systolic spindle that suggested severe stenosis of the arteries could also be detected simultaneously at or just nearby the area of the MMs. MMs occur in accordance with the pulsation, with the greatest predominance at the systole, and may proceed to the early diastole. Eleven MMs presented as a harmonic covibration of musical sound that displayed as 2 or more pairs of mirror-image strings or bands on Doppler waveforms. Most of the MMs sounded like a seagull cry. Four MMs presented as a symmetric continuous string or band, along with the pulsation (Fig 1B, -C). In such cases, MMs sounded like piping from a Chinese bamboo flute. The frequencies of MMs ranged from 130 to 1040 Hz, which equals 5–80 cm/s after angle correction.

TABLE 1:

Distribution and underlying vascular change of 66 musical murmurs in 60 patients

| Location of Musical Murmurs | Severe Stenosis (n = 58)* | Collaterals (n = 5) | C-C Fistula (n = 2) | Moyamoya Disease (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracranial (n = 4) | ||||

| Internal carotid artery | 3 | |||

| Vertebral artery | 1 | |||

| Intracranial (n = 62) | ||||

| Retro-orbital area | 1† | 2 | ||

| Terminal internal carotid artery | 2 | |||

| Middle cerebral artery | 20 | 1 | ||

| Anterior cerebral artery | 9 | |||

| Posterior cerebral artery | 13 | |||

| Anterior communicating artery | 5‡ | |||

| Vertebral artery | 5 | |||

| Basilar artery | 4 |

Note:—C-C fistula indicates carotid cavernous sinus fistula.

Number of musical murmurs.

Transmitted from stenotic terminal internal carotid artery.

Were grouped into anterior cerebral artery by sonographic findings.

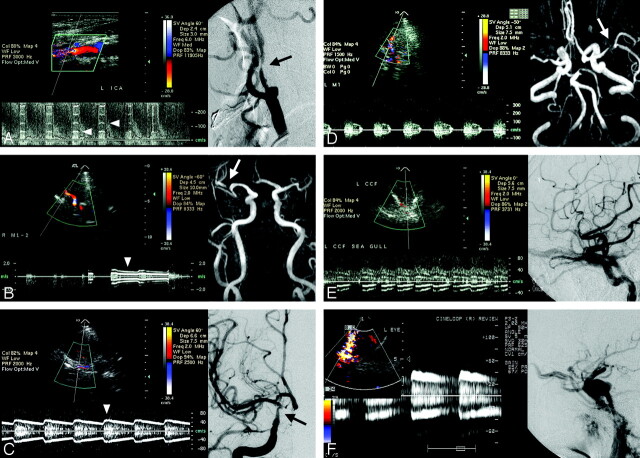

Fig. 1.

A, Color-coded carotid duplex sonography reveals a tight stenotic internal carotid artery with concurrent musical murmurs (arrowheads) and markedly elevated turbulent flow velocities. Stenosis of the internal carotid artery is confirmed by digital subtraction cerebral angiography (arrow).

B, Transcranial color-coded duplex sonography (TCCS) shows musical murmurs (arrowhead) in the proximal portion of the M2 segment of the right middle cerebral artery. MR angiography shows a tight stenotic artery (arrow) at the corresponding artery.

C, TCCS discloses a color flash just below the bifurcation of the right anterior and middle cerebral arteries with continuous musical murmurs (arrowhead) sounding like a Chinese bamboo flute. Cerebral angiography shows a severe stenotic lesion at the right terminal internal carotid artery (arrow).

D, TCCS shows concurrence of turbulent systolic spindle and musical murmurs of the left middle cerebral artery. MR angiography shows a tight stenotic lesion (arrow) at the corresponding artery.

E and F, Transorbital detection of retro-orbital vessels in 2 patients with an angiography-proved carotid cavernous sinus fistula (right) show an abnormal color flash with musical murmurs (left).

Two patients with MMs at the left retro-orbital area were proved to have a carotid cavernous sinus fistula (CCF). Another patient with right retro-orbital MMs had a tight stenotic lesion in the internal carotid siphon. Angiography of the MMs in the extracranial carotid or vertebral artery showed a focal, tight stenotic lesion (70% or greater stenosis). All but one of the angiographic studies of patients with MMs at the areas of the intracranial MCA, PCA, VA, basilar artery, and terminal ICA showed severe stenosis (50% or greater stenosis in diameter) of the appropriate artery. MMs at the MCA area in a 15-year-old boy were found to be associated with Moyamoya disease. Five MMs at the ACA area resulted from the anterior communicating artery that provides intracranial collateral flow for a tight stenosis or occlusion of the unilateral cervical ICA.

Apart from 2 patients with CCF who suffered from pulsatile tinnitus with headache, and 1 young boy with Moyamoya disease who had intracranial hemorrhage, all 57 other patients presented with clinical symptoms and signs related to impaired cerebral circulation. Forty-one patients had a history of ischemic stroke. Nine patients had a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA), and the other 7 patients suffered from dizziness, vertigo, or fainting. Cerebral infarction and TIA occurred more on the side appropriate to the MM (32 patients) than the nonappropriate side (18 patients). All 57 patients had 1 or more risk factors for cerebrovascular disease (Table 2). Hypertension, found in 48 patients (84%), was the most common risk factor, followed by old age (>65 years; 60%), diabetes mellitus (39%), smoking (33%), hyperlipidemia (30%), and ischemic heart disease (17%).

TABLE 2:

Clinical features and risk factors of 57 patients with musical murmurs due to stenotic vascular lesion

| Clinical Presentation | Transient Ischemic Attack | Infarct | Dizziness, Vertigo, and Faintness | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 9 | 41 | 7 | 57 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 8 | 34 | 6 | 48 |

| Old age (>65 y) | 6 | 21 | 7 | 34 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | 16 | 4 | 22 |

| Smoking | 5 | 12 | 2 | 19 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 | 11 | 3 | 17 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1 | 7 | 4 | 12 |

| Previous stroke | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Previous transient ischemic attack | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Discussion

Non-MMs are turbulent flows that initiate random vibrations of adjacent structures and do not have pure tone sounds. MMs and non-MMs might be different modes of expression of the same basic mechanism: a certain range of velocities favoring periodic vortex formation (pure tone), and higher velocities producing irregular vortex shedding (turbulence).3 MMs may have a purer tone at a site distal to the source than closer to the source. They might be detected with or without simultaneous turbulent flows, or very close to a high-intensity frequency (with systolic spindles) turbulent flow. For instance, MMs can be detected through an orbital window at the retro-orbital area, a distance from the stenotic lesion of the ICA siphon. Sounds from MMs have been described as a seagull cry, goose cry, honks, or cooing murmur. In this study, we found an unusual pattern of continuous musical murmurs, without interruption between each cardiac cycle, that sounded like piping from a Chinese bamboo flute. Careful detection and proper adjustment of the sonography instrument are necessary to display MMs. For a stenotic lesion with severe turbulent flow, color B-mode sonography shows a strong heterogenous hyperechoic color flash at the stenotic segment of the artery and Doppler shows markedly elevated flow velocity. A high-velocity scale/frequency Doppler detection setting is necessary to display the highest velocity of the turbulent flow. In such a situation, MMs of lower velocities embedded in the Doppler waveforms near the baseline might be overlooked (Fig 2A). For a better display of MMs, a proper low setting of the Doppler velocity/frequency scale is indicated (Fig 2B).

Fig. 2.

A, Doppler detection of a stenotic posterior cerebral artery with a high velocity scale (0–300 cm/s) shows elevated flow velocity with musical murmurs (arrows) embedded in the lower velocity area near the baseline.

B, Proper adjustment of the Doppler velocity scale to a lower setting (±30 cm/s) clearly demonstrates the musical murmurs (arrowheads).

In cardiac sonographic studies, the frequency, amplitude, and time of occurrence during systole or diastole of a MM are dependent upon the hemodynamics in the vicinity of the vibrating cardiac structure.2 Related cardiac structures include torn valve cusps, redundant or torn chordae tendineae, moderator bands, and the Chiari net. In cerebrovascular detection, Ferguson,7 in 1970, recorded murmurs with musical quality, a relatively high-pitched tone from sacs of intracranial aneurysms exposed at surgery, using a phonocatheter. Only one published study, by Aaslid in 1984,3 has used a sonography system to detect MMs in human cerebral arteries after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). In Aaslid’s series, 15 of 29 patients with recent spontaneous SAH demonstrated MMs in transcranial Doppler recordings. Vasospasm after SAH is the main underlying vascular abnormality of MMs.

It is not surprising that only 6% of MMs were detected in the extracranial cervical arteries. We postulate that the larger lumen diameters and intima-media thickness of the cervical arteries, the higher arterial blood flow, together with the soft tissue surrounding the cervical arteries, cause more randomized than harmonic vibration of the extracranial vascular walls. Fifty-eight of 66 MMs (88%) were found to be associated with severe stenotic atheromatous change in the underlying investigated arteries, with the predominant involvement of the intracranial MCA, followed by the PCA, ACA, intracranial vertebrobasilar arteries, extracranial ICA, VA, and terminal portion of the ICA. Harmonic vibrations of the vessel wall may occur when blood flow passes through the extremely narrowed residual lumen. The vibrations are most prominent at the systole and/or early diastole in each cardiac cycle, with the typical mirror-image strings on Doppler detection. Blood flows inside the lumen might be reduced to various extents. The special continuous MMs throughout the cardiac cycle, sounding like a Chinese bamboo flute in this study, resulted from a strong vibration of the narrowed vessel by turbulent blood flows.

In cases of unilateral ICA occlusion or tight stenosis, the increased flow from the nonstenotic ICA produces harmonic vibrations of the ACA or anterior communicating artery, which serves as a collateral circulation within the circle of Willis. Retro-orbital MMs have never been reported in a CCF before. The characteristic sonographic findings of a CCF include heterogenous color flashes with turbulent flow at the cavernous sinus, and retrograde arterialized superior ophthalmic venous flow in patients with proptosis.8 A pressure gradient and an injection jet through the small fistula with a whistling effect cause a severe vibration of either the arterial or venous vessel walls, and occasionally, produce MMs. One patient who had a MM at the MCA area was found to have Moyamoya disease. The unusually small collateral arteries from the PCA, due to a congenital stenosis of the terminal ICA in Moyamoya disease, may also vibrate with collateral blood flows.

The amplitude and the frequency of the MMs were found to be related to the magnitude of regurgitant flow (the systolic pressure difference between the left ventricle and the left atrium) in patients with a regurgitant mitral bioprosthetic valve.1 In Aaslid’s report,3 the frequency of the pure tone ranged from 140 to 820 Hz, corresponding to flow velocities 73–215 cm/s and correlated with the degree of vasospasm. In this study, the frequency of the pure tone ranged from 130 to 1040 Hz, corresponding to flow velocities 5–80 cm/s after angle correction. Because not every patient underwent a DSA study, it was difficult to evaluate the degree of stenosis in the intracranial arteries with the use of MRA or CTA. Eighty-one percent and 78% stenosis were found by DSA in 2 patients with extracranial ICA stenosis. The peak systolic/end diastolic velocities in Doppler sonography studies at the most turbulent segment of the cervical ICA increased to 600/250 cm/s and 740/280 cm/s, respectively. Both MMs disappeared during follow-up studies after carotid stent placement treatment for the tight stenotic ICAs. Kern et al9 reported that symptomatic MCA disease was an independent predictor for overall and ipsilateral cerebrovascular events. Progression of intracranial arterial stenosis was identified as potential predictor of recurrent ischemic events.9 In this study, the cerebrovascular events were observed more on the side appropriate to the musical murmur (64%). Presence of musical murmur might imply a relative unstable hemodynamic condition and carry a risk of recurrent ischemic event.

In Aaslid’s report,3 MMs were produced by elevated blood flow velocity through severely constricted arteries (vasospasm) after SAH. Vasospasm, although it may be complicated with neurologic deficit, is a transient vascular change after SAH. MMs may disappear after an improvement in the vasospasm. In this study, we did not perform CCD and TCCS in patients with SAH, yet all the MMs were correlated with severe underlying vascular diseases, even in patients with minor clinical symptoms. MMs may disappear in the follow-up study once the degree of arterial stenosis becomes more severe and the blood flow transits from turbulence into silence. However, the pathologic conditions of the diseased vessels will proceed if not properly treated. Because we did not perform a longitudinal follow-up study on the ultrasonographic and clinical outcomes in this study, the natural courses of the patients with MMs are not well understood. However, 1 patient who had MMs at the intracranial vertebrobasilar area, initially presenting as a minor brain stem stroke, suffered a persistent comatous brain stem stroke 1 year later.

Our data reveal that the presence of MMs in CCD and TCCS imply severe underlying vascular diseases that require prompt treatment. Associated pathologic conditions include high-grade stenosis of arteries, small arteries serving as collateral circulation, CCF, and Moyamoya disease. Further cerebral angiographic study is warranted to clarify the underlying pathology. A longitudinal follow-up study in patients with MMs would be helpful for a better understanding of this special phenomenon.

References

- 1.Sabbah HN, Magilliagan DJ, Lakier JB, et al. Hemodynamic determinants of the frequency and amplitude of a musical murmur produced by a regurgitant mitral bioprosthetic valve. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein PD. Origin and clinical relevance of musical murmurs. Int J Cardiol 1983;4:103–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaslid R, Normes H. Musical murmurs in human cerebral arteries after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1984;60:32–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennestri F, Boccardi L, Minardi G, et al. Doppler study of precordial musical murmurs. Am J Cardiol 1989;63:1390–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in the basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg 1982;57:769–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin SK, Ryu SJ, Lee ST, et al. Transcranial color-coded sonography in normal Chinese adults and its clinical applications. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi 1995;18:201–08 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson GG. Turbulence in human intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1970;33:485–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin SK, Ryu SJ, Chu NS. Carotid duplex and transcranial color-coded sonography in evaluation of carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Ultrasound Med 1994;13:557–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kern R, Steinke W, Daffertshofer M, et al. Stroke recurrences in patients with symptomatic vs asymptomatic middle cerebral artery disease. Neurology 2005;65:859–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]