Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the relationship between CT findings of diffuse lung disease and post–transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective review of pre-TAVR CT scans obtained during 2012–2017 was conducted. Emphysema, reticulation, and honeycombing were separately scored using a five-point scale and applied to 10 images per examination. The fibrosis score was the sum of reticulation and honeycombing scores. Lung diseases were also assessed as dichotomous variables (zero vs nonzero scores). The two outcomes evaluated were death and the composite of death and readmission.

Results

The study included 373 patients with median age of 84 years (age range, 51–98 years; interquartile range, 79–88 years) and median follow-up of 333 days. Fibrosis and emphysema were present in 66 (17.7%) and 95 (25.5%) patients, respectively. Fibrosis as a dichotomous variable was independently associated with the composite of death and readmission (hazard ratio [HR], 1.54; P = .030). In those without known chronic lung disease (CLD) (HR, 3.09; P = .024) and those without airway obstruction, defined by a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the forced vital capacity greater than or equal to 70% (HR, 1.67, P = .039), CT evidence of fibrosis was a powerful predictor of adverse events. Neither emphysema score nor emphysema as a dichotomous variable was an independent predictor of outcome.

Conclusion

The presence of fibrosis on baseline CT scans was an independent predictor of adverse events after TAVR. In particular, fibrosis had improved predictive value in both patients without known CLD and patients without airway obstruction.

Supplemental material is available for this article.

© RSNA, 2020

Summary

In an elderly population that underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement, finding of any fibrotic lung disease at preprocedural CT was an independent predictor of subsequent adverse events (composite of rehospitalization and mortality), driven primarily by increased hospital readmissions, particularly in patients without known chronic lung disease and in patients without airway obstruction.

Key Points

■ Fibrotic lung disease at baseline CT was an independent predictor of the composite of death and rehospitalization after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (hazard ratio [HR], 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04, 2.28; P = .030) driven primarily by increased hospital readmissions, independent of other comorbidities and pulmonary function measures (ie, forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], ratio of the FEV1 to the forced vital capacity [FVC], and diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide).

■ Fibrosis at CT had the highest predictive value for adverse events in patients without chronic lung disease (HR, 3.09; 95% CI: 1.16, 8.24; P = .024) by using pulmonary function test measures.

■ Among patients without airway obstruction (ie, those with an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.7) undergoing TAVR, the presence of fibrosis predicted worse outcomes and readmissions (HR, 1.67; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.71; P = .039).

Introduction

The degenerative valvular disease aortic stenosis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. Without treatment, symptomatic severe aortic stenosis is associated with very poor prognosis, particularly in patients with multiple comorbidities. Although surgical aortic valve replacement has long been the standard treatment for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is now U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved for patients at high and intermediate surgical risk and is preferred by many patients because of its minimal invasiveness, a quicker recovery, and equivalent outcomes (1–3).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major driver of morbidity and mortality with surgical aortic valve replacement and is, therefore, often the reason to prefer TAVR. Nonetheless, preexisting lung disease also greatly increases the risk of complications after TAVR. Some degree of chronic lung disease (CLD) has been observed in 27%–55% of patients undergoing TAVR (4–7). Respiratory disease is the most common reason for readmission within 30 days after TAVR (8). Among patients undergoing TAVR, moderate or severe CLD is an independent predictor of pulmonary morbidity, prolonged hospital stay, and subsequent mortality (4,9,10).

Accurate diagnosis of CLD in patients with aortic stenosis remains a challenge because interstitial and alveolar edema can contribute to airway compression and confound pulmonary function test (PFT) measures (11,12). PFTs should be performed when patients are euvolemic, because the mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) can improve by up to 35% after treatment of heart failure with diuresis (13). Conversely, some patients with concomitant symptoms of CLD and aortic stenosis do not improve after aortic valve replacement, possibly because of unresolved lung disease (7). This confounder could contribute to the inconsistent prognostic value of CLD, with several trials demonstrating baseline CLD to be an independent predictor for post-TAVR mortality (14,15) and several trials demonstrating the contrary (16–18). Regardless, pulmonary complications are a common cause of morbidity and mortality after TAVR and highlight a pressing need for more accurate risk stratification based on baseline pulmonary disease status (19).

Contrast material–enhanced CT angiography scans obtained for pre-TAVR planning include the lungs and permit assessment for structural lung disease. Several scoring methods for quantifying pulmonary abnormalities at chest CT have been previously devised (20–24). The objective of our study was to evaluate whether the identification of parenchymal abnormalities, namely fibrosis and emphysema, in the lungs of patients undergoing TAVR is predictive of adverse outcomes independent of known risk factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study approved by our institutional research board with waiver of informed consent. Adults who underwent commercial TAVR during 2012–2017 were identified. Patients were excluded if they lacked preprocedural CT scans of the chest or did not undergo TAVR. We collected age, sex, body mass index, Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score, left ventricular ejection fraction, smoking history, home oxygen use, and severity of CLD from our internal TAVR database, which follows the same data definitions as the STS and/or American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry™. Preprocedural status was evaluated using New York Heart Association functional class and 5-meter walk test. The outcomes measured were (a) all-cause death and (b) the composite of death and readmission.

Assessment of CLD Severity

FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC ratio, and percentage of predicted diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (Dlcopred) data were extracted from pre-TAVR PFTs. Severity of CLD was classified according to the Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry definition: none; mild, FEV1 of 60%–75% for predicted and/or chronic inhaled or oral bronchodilator therapy; moderate, FEV1 of 50%–59% for predicted and/or chronic steroid therapy aimed at lung disease; severe, FEV1 of less than 50% for predicted and/or room air Pao2 less than 60 mm Hg or room air Paco2 greater than 50 mm Hg. Airway obstruction was defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7 per the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

CT Protocol and Scoring of Lung Disease

At our institution, pre-TAVR CT angiography examinations were performed on a third-generation dual-source CT scanner (SOMATOM Force; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) with a spiral acquisition and pitch of 2.5. Axial images were reconstructed using soft tissue (Bv40) and lung (BI57) kernels at 3-mm and 0.75-mm slice thickness and exported to the picture archiving and communication system.

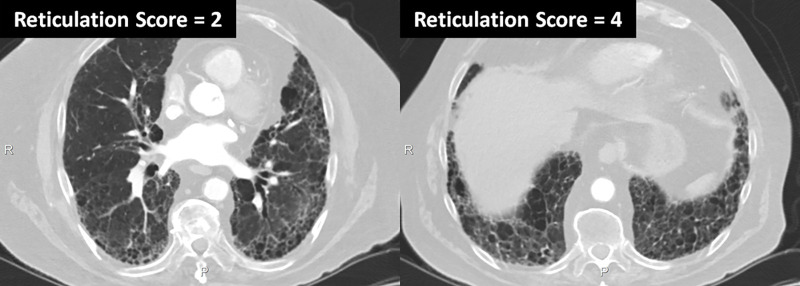

Ten axial CT images of the lungs were selected at regular intervals spaced equally apart from the lung apices to bases (Fig 1). A thoracic radiologist with 5 years of postgraduate experience (C.T.L.) reviewed the scans while blinded to clinical information. Visual scoring was performed separately for each of the three types of lung disease: emphysema, reticulation, and honeycombing (Fig 2). Each CT image was visually scored for the presence of each lung disease on a five-point scale: 0, no disease; 1, 1%–25% lung involvement; 2, 26%–50% lung involvement; 3, 51%–75% lung involvement; and 4, 76%–100% lung involvement (24). The summation of scores for the 10 images was then recorded for the patient. The reticulation and honeycombing scores were combined to produce the fibrosis score. The presence of fibrosis was defined as a fibrosis score of at least 1. To assess interobserver agreement for lung disease, 20% of cases were randomly selected and graded by another radiologist with 4 years of thoracic imaging expertise (A.H.).

Figure 1:

Division of chest CT data set into 10 contiguous axial slices.

Figure 2:

Scoring of reticulation on two axial CT images at different levels.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the median ± interquartile range and were compared by using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were compared with the χ2 test. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to evaluate survival over a follow-up period of up to 16 months and to generate 1-year survival estimates. Curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Emphysema and fibrosis at CT were each expressed as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable in two separate Cox proportional hazards models. All models included FEV1, FEV1/FEV ratio, current or prior smoker (within 1 year), home oxygen use, age, pre-TAVR left ventricular ejection fraction, mean aortic valve gradient (in millimeters of mercury), prior cardiac surgery, diabetes mellitus, history of coronary artery disease, New York Heart Association class, and STS risk score. We also included any variables with a statistically significant difference (P < .05 by univariate comparison) between groups with and without fibrosis and/or emphysema.

To investigate whether FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, Dlcopred, or STS risk score missingness were associated with outcome, we generated Cox proportional hazards models with outcome as the dependent variable and missingness of PFT parameters or STS risk score as the only independent variable. As a sensitivity analysis, we again generated our Cox proportional hazards model with multiple imputation for FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, Dlcopred, and the STS risk score (using the mi impute mvn command [iterative Markov chain Monte Carlo method] with 10 imputations and a burn-in period of 100; the independent variables of sex, history of transient ischemia attack or stroke, home oxygen use, and history of hostile chest were used to generate imputed values).

We performed additional Cox models for CT fibrosis in the following patient subgroups: (a) no CLD, (b) mild CLD, (c) moderate or severe CLD, (d) FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7, and (e) FEV1/FVC ratio greater than or equal to 0.7. Percent agreement and κ coefficients were used to determine interobserver agreement for CT findings of emphysema and fibrosis. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 15.1 (Stata, College Station, Tex).

Results

Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among 373 patients undergoing TAVR, the median age was 84 years (range, 51–98 years; interquartile range, 79–88 years), and 53.1% of the patients were women. The median follow-up period was 333 days (range, 0–514 days). CLD was present in 74.9% of the patients, classified as mild in 125 (34.1%), moderate in 93 (25.3%), and severe in 57 (15.5%). Nineteen (5.1%) patients were smokers within the past year, and 46 (12.3%) were using home oxygen. Patients with emphysema had emphysema scores ranging between 1 and 33 (median, 6; interquartile range, 2–12). Patients with fibrosis had fibrosis scores ranging between 1 and 34 (median, 5; interquartile range, 3–11). Of 373 patients, 95 (25.5%) had emphysema at CT, 66 (17.7%) had fibrosis at CT, and 24 (6.4%) had both.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by Presence or Absence of CT Abnormality

FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC ratio, and Dlcopred data were available in 352 (94.4%), 345 (92.5%), 350 (93.8%), and 255 (68.4%) of the patients, respectively. Missingness of FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC ratio did not correlate with outcome, whereas Dlcopred missingness correlated with death and readmissions (hazard ratio [HR], 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21, 2.20; P = .001) (Table E1 [supplement]). In 45 of 94 (48%) patients with partial PFT examinations, Dlcopred could not be obtained because of technical limitations, mostly because of patients’ inability to perform the maneuver. FEV1 and FVC were tightly correlated, with a correlation coefficient of 0.87. In comparison, FEV1/FVC ratio and Dlcopred each had a weaker correlation with FEV1 (correlation coefficients of 0.38 and 0.42, respectively).

Characteristics of Patients with CT Abnormality

Patients with emphysema compared with patients without emphysema had a lower FEV1 (70% vs 80.0%, P = .003) and more prevalent current or recent smoking history (16.8% vs 1.1%, P < .001) and home oxygen use (29.5% vs 6.5%, P < .001). Dlcopred was decreased in patients with versus those without emphysema (60% vs 75%, P < .001) and in patients with versus those without fibrosis (59% vs 75%, P < .001). The proportion of individuals with moderate or severe CLD was significantly higher (57.4% vs 35.2%, P < .001) in patients with emphysema compared with those without emphysema but was not significantly different between patients with and patients without fibrosis (37.9% vs 41.5%, P = .59).

The emphysema score was significantly higher in the group with moderate or severe CLD versus the group with mild or no CLD (4.2 vs 1.1, P < .001), whereas the fibrosis score was not significantly different between the same groups (1.6 vs 1.5, P = .593). The distributions of CT fibrosis and emphysema scores were positively skewed with most of the patients having limited extent of disease (Figs E1, E2 [supplement]).

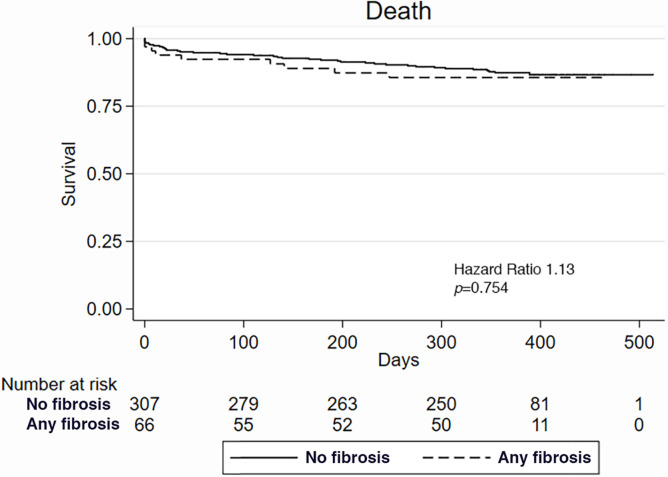

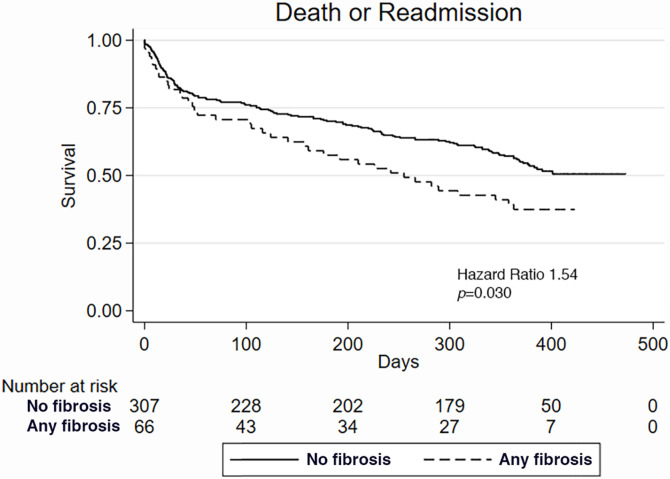

Clinical Outcomes

Pulmonary fibrosis at CT.—The composite of death and readmission at 1 year occurred more frequently in patients with CT evidence of fibrosis compared with those without fibrosis (62.6% vs 43.6%, P = .02; Fig 3a, 3b), driven mainly by increased readmissions. Three hundred thirty patients (88.5%) had full covariate data and therefore were included in our Cox models. CT fibrosis score was a predictor of death and readmission (HR, 1.04; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.08; P = .034; Table 2), whereas the other clinical and functional parameters were not statistically significant predictors. Neither current or recent smoking (HR, 0.49; 95% CI: 0.19, 1.26; P = .139) nor home oxygen use (HR, 1.42; 95% CI: 0.15, 2.30; P = .150) predicted the composite of death and readmission.

Figure 3a:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate the difference in (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT and the difference in (c) death and (d) death or readmission in patients with and those without emphysema at CT.

Figure 3b:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate the difference in (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT and the difference in (c) death and (d) death or readmission in patients with and those without emphysema at CT.

Table 2:

Cox Proportional Hazards Models Examining Correlation between Fibrosis and Composite of Death and Readmissions

As a dichotomous variable, the presence of fibrosis at CT was significantly associated with death or readmission (HR, 1.54; 95% CI: 1.04, 2.28; P = .030; Table 2). Dlcopred was independently predictive for death and readmission (HR, 0.99; 95% CI: 0.98, 0.99; P = .049) when the Cox regression model contained only non-CT variables. The Cox proportional hazards model including Dlcopred showed a consistent predictive value of fibrosis presence at CT (HR, 1.77; 95% CI: 1.08, 2.89; P = .023; Table 2), and this was also the case for a separate model with multiple imputation for FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, Dlcopred, and STS risk score (HR, 1.49; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.19; P = .041).

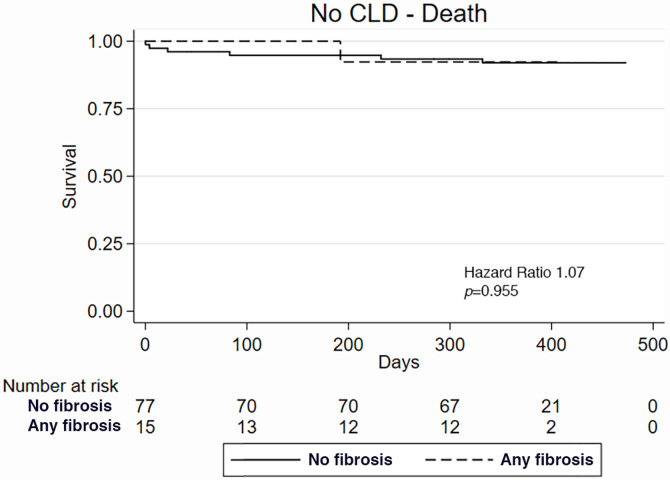

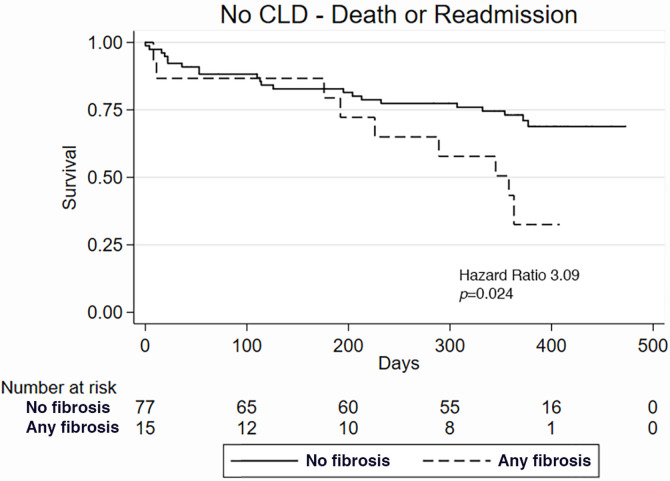

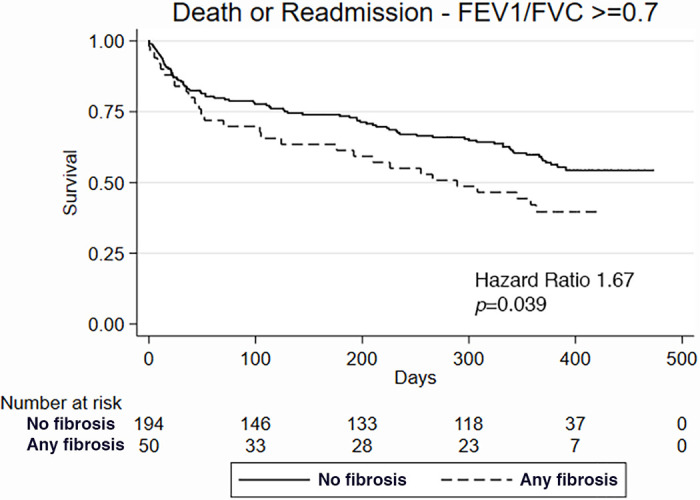

In patients without CLD (n = 92; Table 3), the presence of fibrosis at CT was associated with more adverse events at 1 year (67.5% vs 26.9%, P = .02; Fig 4a, 4b), again driven by increased readmissions. CT evidence of fibrosis was a powerful predictor of adverse events in those without CLD (HR, 3.09; 95% CI: 1.16, 8.24; P = .024) and in patients without airway obstruction (HR, 1.67; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.71; P = .039; Fig 5). In the remaining subgroups (mild CLD; moderate or severe CLD; and airway obstruction defined by an FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7), presence of any fibrosis showed predictive value consistent with the overall finding, although the results were not statistically significant, likely because of the lower number of patients in each subgroup.

Table 3:

Baseline Characteristics in Subgroup without Chronic Lung Disease

Figure 4a:

Among individuals without chronic lung disease (CLD), Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing the outcomes of (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT.

Figure 4b:

Among individuals without chronic lung disease (CLD), Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing the outcomes of (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT.

Figure 5:

Among individuals with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) greater than or equal to 0.7, Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing the outcome of death or readmission in patients with and without fibrosis at CT.

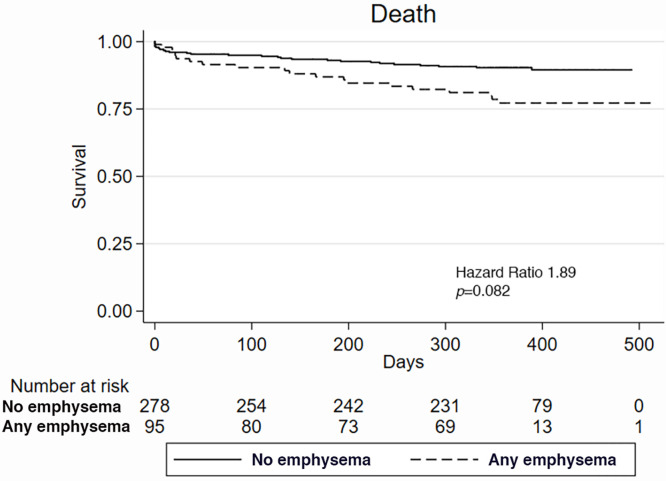

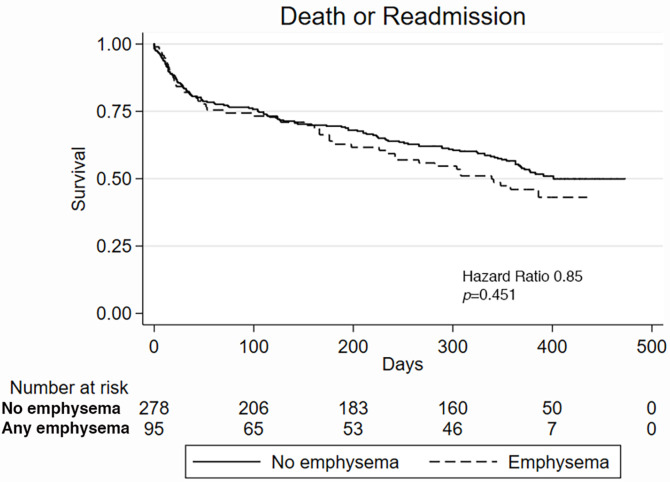

Emphysema at CT.—CT evidence of emphysema was not associated with death or readmission at 1 year (54.0% vs 44.7%, P = .26; Fig 3c, 3d). We performed Cox models on 329 patients (88.2%) with full covariate data. CT emphysema score was not a predictor of death and readmission (HR, 0.99; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.02; P = .423), nor was the presence of any emphysema (HR, 0.85; 95% CI: 0.55, 1.30; P = .452). None of the clinical or functional parameters in models containing emphysema were independent predictors of outcomes.

Figure 3c:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate the difference in (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT and the difference in (c) death and (d) death or readmission in patients with and those without emphysema at CT.

Figure 3d:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate the difference in (a) death and (b) death or readmission in patients with and those without fibrosis at CT and the difference in (c) death and (d) death or readmission in patients with and those without emphysema at CT.

Interobserver agreement.—The interobserver agreement for the presence of fibrosis and emphysema was 88% and 96%, respectively, with moderate agreement by κ analysis (κ coefficients of 0.62 and 0.78, respectively). Agreement for the exact fibrosis score was comparably lower, with 77% agreement and a κ of 0.35.

Discussion

In this study evaluating the association of CT findings of emphysema and fibrosis with outcomes after TAVR we found that (a) fibrotic lung disease at pre-TAVR CT predicts worse outcomes, driven by increased rehospitalizations, independent of other comorbidities and PFT results (FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and Dlcopred), (b) any amount of fibrosis at CT is a strong predictor of adverse events in patients without CLD and in patients without airway obstruction, and (c) emphysema at CT is not associated with subsequent outcomes independent of other comorbidities and pulmonary function measures.

Our study showed that basing preprocedural risk assessment on comorbidities and pulmonary function values results in an incomplete outlook of the pulmonary status of patients undergoing TAVR. FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and Dlcopred were not independent predictors of a worse outcome in models that included CT finding of any fibrosis. Our TAVR population consisted heavily of elderly individuals, in whom PFTs can be limited because of patient inability to fully participate and/or concomitant pulmonary edema related to valvular dysfunction. Accordingly, many of the patients who were unable to provide Dlcopred were likely sicker individuals with worse outcomes. Given the additional difficulty in interpreting PFTs in patients with comorbid cardiac diseases, these results emphasize the importance of lung disease assessment at preprocedural CT examinations.

It is well established that the presence of interstitial lung abnormalities identified by using CT is correlated with morbidity and mortality in the general population (25–27). Whether fibrosis itself has an independent effect on morbidity and mortality in the TAVR population or reflects a higher-risk population is unclear. Among patients with COPD, cardiovascular disease is a more common cause of death than respiratory disease (28). A study of patients who underwent TAVR found acute pulmonary complications to be a rare (1.5%) occurrence associated with concomitant pulmonary disease (including interstitial pneumonia and COPD) and with relatively high mortality (29). Nevertheless, patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are prone to developing an acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia after thoracic surgery and procedures (30).

Although TAVR is less invasive and better tolerated than surgical aortic valve replacement, 40% of patients who undergo TAVR develop systemic inflammatory response syndrome within 48 hours after TAVR (31). This results in a significant elevation of proinflammatory cytokines, which has also been described in patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (32). It is important to note that we observed a separation of event curves more than 1 month after TAVR rather than during the perioperative period, implying that procedure-related stressors are unlikely to be the cause. Instead, fibrosis at CT may be a marker of those with worse baseline pulmonary status, who are therefore more susceptible to decompensation from any cause.

Although emphysema was present in over one-quarter of patients, its presence was not associated with increased post-TAVR complications independent of other known risk factors, including FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and home oxygen use. We suspect this is due to both emphysema at CT and PFT changes being reflective of the same obstructive process. Although we did find that a decrease of either FEV1 or FEV1/FVC ratio was associated with worse outcomes, these associations did not reach statistical significance. Further study is needed to determine whether emphysema scores at CT can be used as a substitute risk marker in place of PFT measures.

When scored as either present or absent, interobserver agreement for the presence of CT abnormality was strong. Furthermore, simply the presence or absence of fibrosis was sufficient to independently predict adverse outcomes. In comparison, agreements for the exact fibrosis and emphysema scores were weaker because of the subjective nature of our grading system, which is similar to previous studies. In one study, the interobserver agreements for honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and emphysema were 0.59, 0.42, and 0.43, respectively (33). Similarly, intralobular reticular opacity had modest interobserver agreements with κ coefficients ranging from 0.42 to 0.66 (34). This shows that interpretation of CT findings is variable across radiologists of differing levels of experience with interstitial lung disease. An alternative solution would be to use lung texture analysis software to automatically and reproducibly quantify the extent of interstitial lung disease, which has been shown to be superior to visual scoring as validated by functional correlation with PFTs (35).

Both PFTs and chest CT are typical components of routine pre-TAVR screening examinations. Our results indicate that patients with evidence of fibrotic lung disease at CT have worse subsequent outcomes, in particular a higher rate of readmissions, and that the predictive ability of this CT finding is particularly striking when there is no CLD or airway obstruction. This information may be helpful for counseling patients before the decision to undergo the TAVR procedure. Additional prospective studies are needed to assess the prognostic value of abnormal CT findings and whether affected patients would benefit from closer follow-up.

Limitations

This study included all patients who underwent TAVR, which introduced a selection bias for patients who were deemed likely to benefit from the procedure despite any coexistent pulmonary disease. The utility of our findings in risk stratification and patient selection prior to TAVR could be addressed prospectively in the future. FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and Dlcopred taken together are good predictors of the overall severity of lung disease, with the caveat that airflow obstruction secondary to decompensated heart failure can lead to misdiagnosis and overestimation of COPD severity (11). We were also unable to establish whether the outcomes were directly related to TAVR, whether any of the readmissions were caused by deteriorating pulmonary status, or whether there was any improvement in CLD after TAVR.

Conclusion

Fibrotic lung disease at preprocedural CT was a significant predictor of adverse events after TAVR, driven mainly by increased rehospitalizations, independent of known risk factors and particularly in patients without known CLD and patients without airway obstruction. These results highlight the importance of careful imaging review, as it may help guide clinical decision-making and manage the expectations of patients undergoing TAVR.

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLES

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: C.T.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.J.C. disclosed no relevant relationships. A.H. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.K.H. disclosed no relevant relationships B.T.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. E.K.F. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: author is cofounder and shareholder in HipGraphics; institution has grants from GE as educational support to Hopkins; author receives educational support from Siemens. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. J.R.R. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.L.Z. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: institution receives salary support from Siemens Healthcare for consulting on clinical product; institution receives research grant from American Heart Association. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- CLD

- chronic lung disease

- COPD

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Dlcopred

- predicted diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide

- FEV1

- forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC

- forced vital capacity

- HR

- hazard ratio

- PFT

- pulmonary function test

- STS

- Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- TAVR

- transcatheter aortic valve replacement

References

- 1.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364(23):2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER 2 Investigators. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2016;374(17):1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. ; SURTAVI Investigators. Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2017;376(14):1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dvir D, Waksman R, Barbash IM, et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic lung disease and severe aortic stenosis treated with transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement or standard therapy: insights from the PARTNER trial (placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(3):269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri RM, Gulack BC, Brennan JM, et al. Outcomes of patients with severe chronic lung disease who are undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100(6):2136–2145; discussion 2145–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes DR Jr, Brennan JM, Rumsfeld JS, et al. ; STS/ACC TVT Registry . Clinical outcomes at 1 year following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA 2015;313(10):1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crestanello JA, Popma JJ, Adams DH, et al. Long-term health benefit of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with chronic lung disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10(22):2283–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolte D, Khera S, Sardar MR, et al. Thirty-day readmissions after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the united states: insights from the nationwide readmissions database. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10(1):e004472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crestanello JA, Higgins RS, He X, et al. The association of chronic lung disease with early mortality and respiratory adverse events after aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98(6):2068–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henn MC, Zajarias A, Lindman BR, et al. Preoperative pulmonary function tests predict mortality after surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151(2):578–585, 586.e1–586.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins NM, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, Chalmers GW, Dunn FG, McMurray JJ. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnostic pitfalls and epidemiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11(2):130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magee MJ, Herbert MA, Roper KL, et al. Pulmonary function tests overestimate chronic pulmonary disease in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96(4):1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Light RW, George RB. Serial pulmonary function in patients with acute heart failure. Arch Intern Med 1983;143(3):429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moat NE, Ludman P, de Belder MA, et al. Long-term outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: the U.K. TAVI (United Kingdom Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58(20):2130–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houthuizen P, Van Garsse LA, Poels TT, et al. Left bundle-branch block induced by transcatheter aortic valve implantation increases risk of death. Circulation 2012;126(6):720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamburino C, Capodanno D, Ramondo A, et al. Incidence and predictors of early and late mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in 663 patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2011;123(3):299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unbehaun A, Pasic M, Drews T, et al. Analysis of survival in 300 high-risk patients up to 2.5 years after transapical aortic valve implantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92(4):1315–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012;366(18):1686–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, et al. One-year outcomes of cohort 1 in the Edwards SAPIEN Aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) registry: the European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation 2011;124(4):425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamsu G, Salmon CJ, Warnock ML, Blanc PD. CT quantification of interstitial fibrosis in patients with asbestosis: a comparison of two methods. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagao T, Nagai S, Hiramoto Y, et al. Serial evaluation of high-resolution computed tomography findings in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in usual interstitial pneumonia. Respiration 2002;69(5):413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Best AC, Meng J, Lynch AM, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: physiologic tests, quantitative CT indexes, and CT visual scores as predictors of mortality. Radiology 2008;246(3):935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barr RG, Berkowitz EA, et al. ; COPDGene CT Workshop Group . A combined pulmonary-radiology workshop for visual evaluation of COPD: study design, chest CT findings and concordance with quantitative evaluation. COPD 2012;9(2):151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013;268(2):563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putman RK, Hatabu H, Araki T, et al. ; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators; COPDGene Investigators. Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA 2016;315(7):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araki T, Putman RK, Hatabu H, et al. Development and progression of interstitial lung abnormalities in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(12):1514–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podolanczuk AJ, Oelsner EC, Barr RG, et al. High-attenuation areas on chest computed tomography and clinical respiratory outcomes in community-dwelling adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196(11):1434–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Celli BR. Predictors of mortality in COPD. Respir Med 2010;104(6):773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimura T, Yamamoto M, Kagase A, et al. The incidence, predictive factors and prognosis of acute pulmonary complications after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;25(2):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. an international working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(3):265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinning JM, Scheer AC, Adenauer V, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome predicts increased mortality in patients after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J 2012;33(12):1459–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papiris SA, Tomos IP, Karakatsani A, et al. High levels of IL-6 and IL-8 characterize early-on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis acute exacerbations. Cytokine 2018;102:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh SL, Calandriello L, Sverzellati N, Wells AU, Hansell DM; UIP Observer Consort . Interobserver agreement for the ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT criteria for a UIP pattern on CT. Thorax 2016;71(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumikawa H, Johkoh T, Colby TV, et al. Computed tomography findings in pathological usual interstitial pneumonia: relationship to survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177(4):433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacob J, Bartholmai BJ, Rajagopalan S, et al. Automated quantitative computed tomography versus visual computed tomography scoring in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: validation against pulmonary function. J Thorac Imaging 2016;31(5):304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.