Abstract

An esophagopericardial fistula is a rare complication of esophageal malignancy, trauma, or surgery. Imaging is a cornerstone of diagnosis, with detection of pneumopericardium or hydropneumopericardium at imaging raising suspicion for pyopneumopericardium and prompting immediate search for the causative pathologic process. Given the high associated mortality rate of over 50% for patients with esophagopericardial fistulas, early diagnosis and intervention are vital.

Supplemental material is available for this article.

© RSNA, 2020

Summary

In patients with a history of esophageal disease and/or intervention, detection of pneumopericardium should prompt search for an esophagopericardial fistula without delay.

Key Points

■ Esophagopericardial fistulas are rare entities that may have dramatic imaging presentations and severe clinical consequences for patients.

■ Radiologic studies using oral contrast material can be invaluable in confirming the diagnosis.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department after “feeling sick” for 2 days, with mild shortness of breath and chills, but no documented fever, chest pain, or abdominal pain. He carried a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction, treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation and subsequent esophagogastrectomy with Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy and surgical jejunostomy tube placement 1 month prior. Postoperative course had been complicated by a known contained leak at the esophagojejunal anastomosis, treated by a drain placed at the time of surgery and keeping the patient on a nothing-by-mouth regimen with nutrition administered by the surgical jejunostomy tube. The patient tolerated tube feeds appropriately and was discharged on a nothing-by-mouth status, on tube feeds, and with the drain in place, but without confirmed resolution of the contained leak.

Baseline emergency department laboratory studies were obtained, which were notable for an elevated white blood cell count of 23 400/µL (23.4 × 109/L). Frontal and lateral radiographs obtained in the emergency department (Fig 1) demonstrated a large air-fluid level in the mediastinum. Follow-up CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed with an oral contrast agent (Fig 2), confirming the large hydropneumopericardium. Given the patient’s surgical and radiation history coupled with the elevated white blood cell count and clinical presentation, these imaging findings were suspicious for pyopneumopericardium. Oral contrast was seen in the alimentary tract as well as in an extraenteric collection, though without detectable extravasation into the pericardial space.

Figure 1a:

(a) Frontal and (b) lateral radiographs demonstrate widening of the cardiac silhouette. Note air on both sides outlining the pericardium on the frontal view (thin arrows), and an air-fluid layer in the anterior chest on lateral view (thick arrows), indicative of hydropneumopericardium. Pleural effusions and a left lower thorax surgical drain are also present.

Figure 2:

Axial CT image of the chest without intravenous contrast but with oral contrast demonstrates an air-fluid level (thick arrows) within the pericardial sac (thin arrows), confirming the large hydropneumopericardium. Oral contrast is seen in the lumen of the visualized alimentary tract (L) as well as a loculated extraluminal collection (*), consistent with a chronic anastomotic leak. Bilateral small pleural effusions are also present, left larger than right.

Figure 1b:

(a) Frontal and (b) lateral radiographs demonstrate widening of the cardiac silhouette. Note air on both sides outlining the pericardium on the frontal view (thin arrows), and an air-fluid layer in the anterior chest on lateral view (thick arrows), indicative of hydropneumopericardium. Pleural effusions and a left lower thorax surgical drain are also present.

At surgery, a large pericardial abscess was confirmed. Bilateral pericardial windows were created, and the pericardium was drained of “abundant purulent material.” Cultures of the pericardial fluid grew Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli. The patient’s immediate postoperative course was uneventful, with the patient beginning endoscopic vacuum sponge therapy on postoperative day 1. On postoperative day 7, he underwent an upper endoscopy with removal of the endoscopic vacuum and placement of an esophageal stent to cover the surgical anastomosis. The following day, esophagography with water-soluble contrast was performed (Fig 3, Movie [supplement]), demonstrating extraluminal contrast at the level of the anastomosis, with tracking into the pericardial sac, confirming an esophagopericardial fistula.

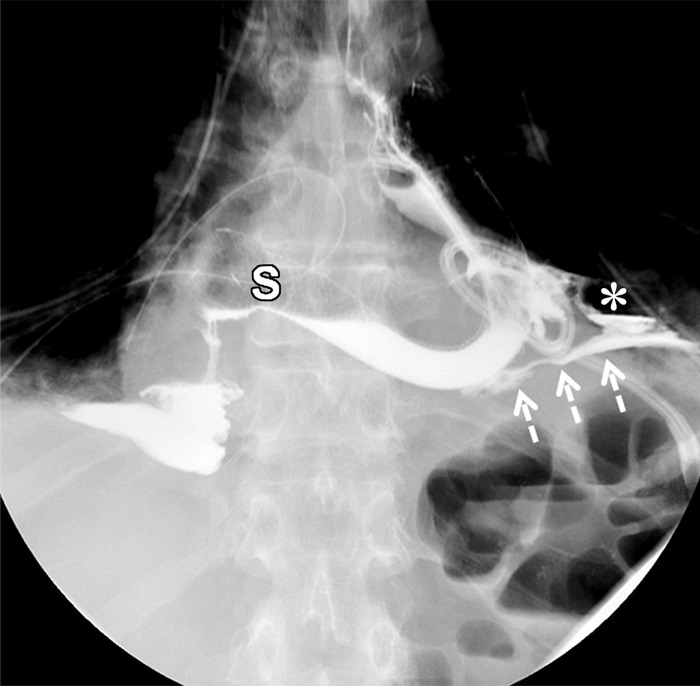

Figure 3a:

Frontal images from an esophagogram performed with water-soluble contrast material after surgical drainage of the pericardium and subsequent placement of an esophageal stent (S) across the esophagojejunostomy. (a) Early image in the study demonstrates persistent extraluminal contrast (dashed arrows) outside the alimentary tract, coursing toward midline. The loculated extraluminal collection depicted in Figure 2 remains and is again seen (*). (b) More delayed image from the study demonstrates oral contrast filling the pericardial space (thin arrows), confirming the presence of a persistent esophagopericardial fistula. Bilateral surgical drains are also present.

Figure 3b:

Frontal images from an esophagogram performed with water-soluble contrast material after surgical drainage of the pericardium and subsequent placement of an esophageal stent (S) across the esophagojejunostomy. (a) Early image in the study demonstrates persistent extraluminal contrast (dashed arrows) outside the alimentary tract, coursing toward midline. The loculated extraluminal collection depicted in Figure 2 remains and is again seen (*). (b) More delayed image from the study demonstrates oral contrast filling the pericardial space (thin arrows), confirming the presence of a persistent esophagopericardial fistula. Bilateral surgical drains are also present.

Movie:

Frontal images from the same esophagogram illustrated in Figure 3 demonstrate cardiac motion with the heart bathed in intrapericardial contrast.

Despite this finding, the patient gradually improved clinically with conservative management, tube feeds, and total parenteral nutrition. Follow-up esophagrams demonstrated a persistent contained leak, but without communication to the pericardium. Even though there was never any confirmed resolution of the anastomotic leak, the patient was discharged on postoperative day 27 with intravenous antibiotics and tube feeds with surgical drains still in place.

In the months following discharge, however, the patient was hospitalized several times for various maladies, including dehydration with acute kidney injury, melena, intractable vomiting, and failure to thrive. He died 5 months after the diagnosis of esophagopericardial fistula.

Discussion

Fistulas between the esophagus and pericardium are rare but potentially fatal, with mortality rates higher than 50% (1). As in this case, they often result from complications of malignancy or esophageal injury, either from surgery, ablation procedures for the treatment of atrial fibrillation, or caustic injury (2). The clinical presentation of these fistulas is highly variable, including chest pain, fevers, dysphagia, shortness of breath, malaise, and rarely cardiac tamponade.

While direct visualization of the fistula can be challenging radiographically, the diagnosis of pneumopericardium can be established with appropriate radiologic and/or echocardiographic studies. In this particular case, chest radiographs alone were sufficient to diagnose pneumopericardium. However, when the amount of air in the pericardium is smaller, it easily could be mistaken for the much more common, and less ominous, diagnosis of pneumomediastinum. While both pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium may demonstrate the “continuous diaphragm sign” (though not present in this case), they may be distinguished by how far cephalad the air tracks on upright radiograph. Air in the pericardium will not extend above the pericardial reflections along the vascular trunk, whereas air in the mediastinum often will. Regardless, in cases that are unclear, CT may clarify the diagnosis.

Echocardiography not only can localize air within the pericardium but also allows assessment for tamponade physiology. Ultimately, however, the definitive diagnosis of an esophagopericardial fistula may require an examination using an oral contrast agent, such as CT or, as in this case, esophagography. Alternatively, an intraoperative diagnosis could be made with either direct visualization of the connection, or intraesophageal administration of an obvious visual agent, such as methylene blue dye, that then accumulates in the pericardium. It is unclear why the initial CT scan in the emergency department did not demonstrate accumulation of oral contrast in the pericardium, whereas the subsequent esophagram demonstrated it quite clearly. This may be in part due to differences in patient positioning between the two examinations during the administration of the oral contrast agent, as well as the fact that the esophagography provides images over multiple points in time as opposed to the single point in time seen on CT.

The exact cause of the fistula in this patient remains open to speculation as the fistula was never identified surgically. However, the patient had several risk factors for fistula development: malignancy, radiation therapy, surgery, and chronic inflammation postoperatively secondary to a persistent anastomotic leak. Any or all of these may have contributed to fistula creation.

Initial management of esophagopericardial fistulas often depends on the clinical presentation. In cases of cardiac tamponade, urgent decompression of the pericardial contents either surgically or percutaneously is warranted (3). The advantage of the former is that it may allow for simultaneous direct visualization and repair of the causative fistula if identified. Once the patient is hemodynamically stable, more conservative measures could also be taken to foster closure of the fistula. These include bowel rest, broad spectrum antibiotics, endoscopic vacuum therapy, and esophageal stent placement across the fistula (4,5). However, esophageal stent placement should be considered a temporary measure, as long-term stent placement has also been associated with serious complications, including perforation, bleeding, and even new fistula formation (2,6).

Conclusion

This case demonstrates purulent pericarditis with massive pyopneumopericardium secondary to an esophagopericardial fistula complicating an esophagogastrectomy. The imaging presented highlights the value and complementary nature of radiography, CT, and fluoroscopy in early detection and confirmation of this rare diagnosis. Management of these cases frequently requires surgical intervention, particularly if cardiac tamponade is suspected, though more conservative approaches have also been reported, if only temporizing.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: A.W.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.J.D. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.T.F. disclosed no relevant relationships.

References

- 1.Ladurner R, Qvick LM, Hohenbleicher F, Hallfeldt KK, Mutschler W, Mussack T. Pneumopericardium in blunt chest trauma after high-speed motor vehicle accidents. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23(1):83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farkas ZC, Pal S, Jolly GP, Lim MMD, Malik A, Malekan R. Esophagopericardial fistula and pneumopericardium from caustic ingestion and esophageal stent. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107(3):e207–e208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagres N, Kottkamp H, Piorkowski C, et al. Rapid detection and successful treatment of esophageal perforation after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: lessons from five cases. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006;17(11):1213–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunch TJ, Nelson J, Foley T, et al. Temporary esophageal stenting allows healing of esophageal perforations following atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006;17(4):435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Möschler O, Nies C, Mueller MK. Endoscopic vacuum therapy for esophageal perforations and leakages. Endosc Int Open 2015;3(6):E554–E558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu K, You Q, He SJ, Mo HL. Angiographic and interventional management for a esophagopericardial fistula. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2014;37(1):247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]