Abstract

SUMMARY: Intracranial calcifications may represent calcified cerebral emboli. Calcified emboli may be overlooked even though cerebral CT is widely used as a stroke assessment. We report 4 cases of calcified cerebral emboli and demonstrate the value of CT in the diagnosis and temporal evaluation of such emboli.

Embolic stroke is a major cause of mortality and morbidity. Cerebral emboli can originate from many sites and vary in their histopathologic composition.1 Calcified cerebral emboli are rare,2 and literature on calcified cerebral emboli is scanty. Calcified cerebral emboli secondary to aortic valve disease have been previously reported.3–5 To our knowledge, calcified cerebral emboli in the posterior cerebral circulation have not been reported previously. We report 4 cases of calcified cerebral emboli and demonstrate the value of CT in the diagnosis and temporal evaluation of such emboli.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 66-year-old man presented with acute onset of right-sided hemiparesis, right facial droop, and dysphasia. A noncontrast CT of the brain revealed a calcific attenuation in the region of the distal M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (Fig 1A). There was no evidence of cerebral infarction, with normal gray-white matter differentiation identified in the left cerebral hemisphere (Fig 1B). A CT angiogram (Fig 1C) was obtained from the level of the aortic arch to the circle of Willis, which showed a calcific attenuation in the distal left M1 segment, consistent with a calcified cerebral embolus. High-grade stenosis of the left internal carotid artery with eccentric calcified plaque was also identified (Fig 1D). Because the patient presented more than 3 hours after the onset of symptoms, thrombolysis was not administered. A follow-up noncontrast CT showed a large area of ischemic infarction in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery with loss of gray-white differentiation and local mass effect (Fig 1E). The patient was then placed on antiplatelet therapy and made an excellent recovery, regaining grade 4 of 5 power in both right upper and lower limbs after 3 months. The patient’s dysphasia also dramatically improved with intensive speech therapy. Some residual weakness persisted in both right upper and lower limbs, and the patient also had residual word-finding difficulties. Left carotid endarterectomy was successfully performed 6 months after the initial presentation.

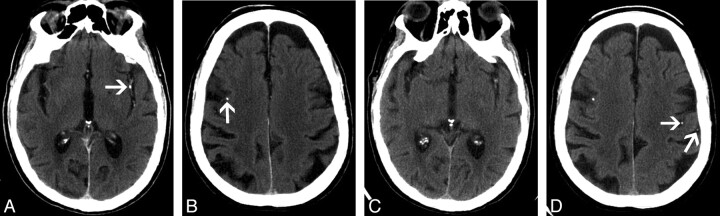

Fig 1.

A 66-year-old man with a calcified cerebral embolus to the left middle cerebral artery.

A, Axial 2.5-mm image from a noncontrast brain CT scan shows a calcified embolus in the distal M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (arrow).

B, Axial 2.5-mm image obtained at a higher level shows a normal left parietal lobe, with normal gray-white matter differentiation.

C, Coronal image from a CT angiogram from the level of the aortic arch to the circle of Willis shows calcified embolus in the distal M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (arrow).

D, Coronal oblique image from the same examination as C shows high-grade stenosis of the left internal carotid artery with extensive calcified plaque.

E, Follow-up noncontrast brain CT scan, obtained 1 day after A and B, shows an acute infarct in the left middle cerebral artery territory with loss of normal gray-white matter differentiation and local mass effect.

Case 2

A 70-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with syncope and bradycardia. Investigations included a cardiac catheterization study, which was complicated by sudden onset of right-sided weakness and dysphasia after the procedure. A left middle cerebral territory infarct was suspected, and a noncontrast CT of the brain was performed (Fig 2A, -B). A calcific attenuation was identified in a Sylvian branch of the left middle cerebral artery (Fig 2A). An image from the same CT examination at a higher level showed a calcified gyral attenuation in the cortex of the right frontal lobe (Fig 2B). There was no evidence of cerebral hemorrhage. The patient was treated with intravenous thrombolysis and made an excellent clinical recovery, with complete resolution of the right-sided weakness and dysphasia. Normal power was noted in both upper and lower limbs. A repeat noncontrast brain CT was performed 1 day after thrombolysis. The previously noted calcific attenuation in the region of the left Sylvian fissure was no longer seen within the proximal left middle cerebral artery branch (Fig 2C). At a higher level, the previously noted right-sided cortical calcified attenuation was unchanged (Fig 2D), but 2 new calcified densities were seen in the region of the left precentral gyrus, consistent with downstream migration and fragmentation of the previously identified calcified cerebral embolus.

Fig 2.

A 70-year-old woman with a left middle cerebral artery territory infarct after a coronary angiogram.

A, Axial 2.5-mm image from noncontrast brain CT shows a calcified embolus in a Sylvian branch of the left middle cerebral artery (arrow).

B, Axial 2.5-mm image obtained from the same brain CT as A shows a calcific gyral attenuation in the right frontal lobe (arrow), very likely representing a second calcified cerebral embolus.

C, Axial 2.5-mm image (obtained at the same axial level as A), from noncontrast brain CT performed 1 day after A and B, shows that the previously identified calcified cerebral embolus in a Sylvian branch of the left middle cerebral artery is no longer visualized.

D, Axial 2.5-mm image (obtained at same axial level as B) from the same examination as C shows unchanged cortical attenuation in the right frontal lobe. Two new calcific densities are identified in the left precentral gyrus (arrows), consistent with downstream migration and fragmentation of the previously identified calcified cerebral embolus.

Case 3

A 61-year-old woman with a history of insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus and multiple medical problems presented with renal failure. The patient also had a history of multiple left hemispheric transient ischemic attacks and a left frontal lobe cerebral infarct. Six months before this admission, the patient had undergone successful angioplasty of the supraclinoid portion of the left internal carotid artery. During the current admission, the patient suddenly developed a new right hemiparesis and slurred speech. A noncontrast CT of the brain was performed and revealed a calcified attenuation in the region of the left posterior cerebral artery (Fig 3A). An axial image obtained at a higher level showed a long-standing infarct in the deep white matter of the left frontal lobe (Fig 3B). Thrombolysis was not administered because a renal biopsy had been performed the day previously. The patient’s neurologic status improved a few hours after the CT examination, with residual right upper and lower limb weakness (grade 3 of 5), and rehabilitation was started. The previously noted slurring of speech resolved with intensive speech therapy. Echocardiography showed a normal aortic valve. A CT angiogram showed calcification at the origin of the left vertebral artery and calcified plaques in both carotid bulbs.

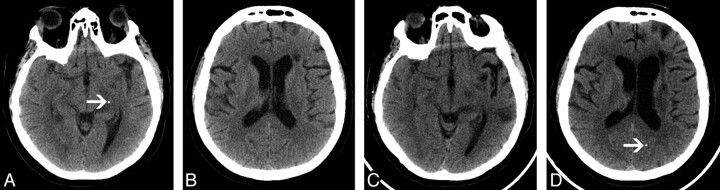

Fig 3.

A 61-year-old woman with a calcified cerebral embolus to the left posterior cerebral artery.

A, Axial 2.5-mm image from noncontrast brain CT shows a calcified cerebral embolus in the left posterior cerebral artery (arrow).

B, Axial 2.5-mm image obtained at a higher level shows a long-standing area of infarction in the periventricular deep white matter of the left frontal lobe.

C. Axial 2.5-mm image (obtained at the same axial level as A), from noncontrast brain CT performed 5 months after A and B, shows that the previously identified calcified embolus is no longer seen in the region of the proximal left posterior cerebral artery. Note the new area of infarction in the left temporal lobe.

D, Axial 2.5-mm image (obtained at the same axial level as B), from the same examination as C, shows downstream migration of the previously identified calcified cerebral embolus into the left occipital lobe (arrow).

A repeat noncontrast CT, performed on a subsequent admission (5 months later), showed an infarct in the left temporal lobe (Fig 3C). The previously identified calcified attenuation was noted to have migrated into the left occipital lobe (Fig 3D). The findings were consistent with migration of a calcified cerebral embolus within the left posterior cerebral artery circulation.

Case 4

An 86-year-old woman presented with acute onset of central chest pain and breathlessness. Electrocardiography and laboratory investigations revealed an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. The patient received intravenous thrombolysis and was transferred to the coronary care unit. Transesophageal echocardiography demonstrated a sclerotic aortic valve and extensive atheroma in the aortic arch. A chest x-ray film showed extensive calcification in the aortic arch.

The patient became confused on day 3 after admission, and a CT brain scan was obtained (Fig 4A). Note was made of a tiny gyral calcification in the posterior right frontal lobe, interpreted as a tiny granuloma or a calcified cavernoma. Five days later, the patient had a ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest and was resuscitated successfully with DC cardioversion. The patient received several rounds of manual chest compressions before successful cardioversion. Following the cardiac arrest, the patient was noted to be confused, with a decreased level of consciousness. No focal neurologic signs were elicited on clinical examination. A repeat CT of the brain was performed, and no evidence of hemorrhage or infarction was identified. A new calcific gyral attenuation was noted in the anterior right frontal lobe (Fig 4B), likely representing a second calcified embolus to the right cerebral hemisphere.

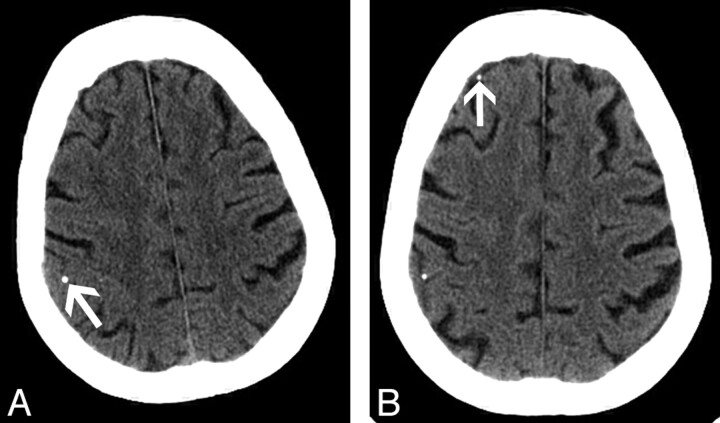

Fig 4.

A 86-year-old woman with new onset of confusion after a recent myocardial infarct.

A, Axial 2.5-mm image from noncontrast brain CT shows a gyral calcification in the posterior right frontal lobe (arrow).

B, Axial 2.5-mm image (obtained at the same axial level as A) from noncontrast brain CT performed after cardiac arrest (5 days after A). The previously identified gyral calcification in the posterior right frontal lobe appears unchanged. Note the presence of a new gyral calcification in the anterior right frontal lobe (arrow), consistent with a calcified cerebral embolus.

Discussion

Many causes of physiologic intracranial calcification exist. Intraparenchymal cerebral calcifications often represent lesions such as calcified granulomas or calcified cavernomas. Although calcified cavernomas can be seen anywhere in the brain parenchyma, calcified cerebral emboli can be seen in the paths of major vessels (cases 1 and 3) or sitting on the brain surface (cases 2 and 4). Mural and eccentric intravascular calcification is commonly seen secondary to atherosclerotic disease. However, as we have demonstrated, intracranial calcifications may be secondary to calcified cerebral emboli that can change in site, size, and attenuation with time.

Calcified cerebral emboli have been previously described secondary to aortic valve disease.3,5,6 However, a prospective study in a large cohort of patients with aortic valve calcification demonstrated that the risk of embolic stroke was not increased.7 Calcified cerebral embolism has been reported secondary to direct carotid manipulation.8 CT findings in spontaneous calcified cerebral emboli secondary to a carotid source have been reported twice before.2,8 In our case 1, the presumed source of the calcified embolus was from calcified plaque in the ipsilateral stenotic internal carotid artery. Calcified cerebral emboli originating from the aortic arch have also been previously reported.9 In our case 2, the calcified cerebral embolus occurred after coronary artery catheterization, a scenario that has been previously described.9 The source of the calcified embolus in our case 3 may have been from the calcified plaque seen at the origin of the left vertebral artery. This patient had a history of widespread atheromatous disease and bilateral carotid stenosis. In our case 4, the likely source of the calcified emboli was from the calcified aortic arch, dislodged by vigorous manual chest compressions. To our knowledge, calcified cerebral emboli in the posterior cerebral circulation have not been reported previously.

All noncontrast images shown in this Case Report are axial 2.5-mm cuts from routine CT head scans. Intracranial calcifications seen on routine noncontrast CT of the head may represent calcified cerebral emboli. In contrast to a previous case report,10 this study documents that intravenous thrombolysis can be effective in the treatment of acute stroke secondary to calcified cerebral emboli. Therefore, an acute calcified cerebral embolus seen on a brain CT in the setting of a patient with acute stroke is not a contraindication for administering intravenous thrombolysis. This information is important when assessing a patient’s likely outcome when commencing thrombolytic therapy.

Conclusions

The presence of calcified cerebral emboli should prompt evaluation of the carotid arteries, the aortic arch, and the heart. The presence of calcified cerebral emboli does not indicate a contraindication to intravenous thrombolysis. Calcified cerebral emboli should not be overlooked when using cerebral CT for stroke assessment.

References

- 1.Rapp JH, Pan XM, Yu B, et al. Cerebral ischemia and infarction from atheroemboli <100 microm in size. Stroke 2003;34:1976–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yock DH. CT demonstration of cerebral emboli. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1981;5:190–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapila A, Hart R. Calcific cerebral emboli and aortic stenosis: detection on computed tomography. Stroke 1986;17:619–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernhet H, Torres GF, Laharotte JC, et al. Spontaneous calcific cerebral emboli from calcified aortic valve stenosis. J Neuroradiol 1993;20:19–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rancurel G, Marelle L, Vincent D, et al. Spontaneous calcific cerebral embolus from a calcific aortic stenosis in a middle cerebral artery infarct. Stroke 1989;20:691–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveria-Filho J, Massaro AR, Yamamoto F, et al. Stroke as the first manifestation of calcific aortic stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2000;10:413–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon A, Lodder J, Cheriex E, et al. Risk of stroke in a cohort of 815 patients with calcification of the aortic valve with or without stenosis. Stroke 1996;27:847–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khaw N, Gailloud P. CT of calcific cerebral emboli after carotid manipulation. AJR Am J Reontgenol 2000;174:1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirk GR, Johnson JK. Computed tomography detection of a cerebral calcific embolus following coronary catheterization. J Neuroimaging 1994;4:241–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halloran JI, Bekavac I. Unsuccessful tissue plasminogen activator treatment of acute stroke caused by a calcific embolus. J Neuroimaging 2004;14:385–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]