Abstract

In this paper, we present the design, fabrication, and characterization of a compact 4 × 4 piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer (pMUT) array and its application to photoacoustic imaging. The uniqueness of this pMUT array is the integration of a 4 μm-thick ceramic PZT, having significantly higher piezoelectric coefficient and lower stress than sol-gel or sputtered PZT. The fabricated pMUT array has a small chip size of only 1.8 × 1.6 mm2 with each pMUT element having a diameter of 210 μm. The fabricated device was characterized with electrical impedance measurement and acoustic sensing test. Photoacoustic imaging has also been successfully demonstrated on an agar phantom with a pencil lead embedded using the fabricated pMUT array.

Keywords: Microelectromechanical Systems, Piezoelectric Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducers, PMUT Array, Ceramic PZT, Photoacoustic Imaging, Endoscopic Imaging

I. Introduction

PHOTOACOUSTIC imaging (PAI), as a thriving noninvasive imaging technique with good optical contrast, high resolution and large imaging depth, has shown great potential in brain functional imaging [1], detection of breast tumors [2], and early diagnosis of arthritis [3]. In PAI, a short-pulsed laser is used to illuminate the tissue, which will absorb optical energy and generate a pressure pulse in ultrasonic frequencies due to the rapid thermoelastic expansion. One of the key components in a photoacoustic imaging system is an ultrasonic transducer whose sensitivity and bandwidth will directly affect the signal to noise ratio (SNR) and imaging resolution of the system. Current commercial ultrasound detectors are dominated by bulk piezoelectric transducers based on the thickness extension mode, which have been widely used in bulk PAI setups [4]–[6].

However, to realize the benefits of the PAI in the clinical environments, such as early cancer detection in human gastrointestinal tract, breast tumor margin evaluation and resection in the surgery, it is necessary to develop endoscopic PAI systems with miniaturized ultrasonic transducers [7], [8]. Conventional ultrasonic transducers have large size and are complicated to be fabricated into arrays, causing a big barrier for integrating them into endoscopic PAI probes that typically have outer diameters of 3-6 mm [9]–[11]. Miniaturization of the imaging devices while keeping the high performance as that of bulk PAI setup becomes a challenge.

With the advancement of the microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology, micromachined ultrasonic transducers (MUTs), including capacitive MUTs (cMUTs) and piezoelectric MUTs (pMUTs), have been developed with the size much reduced. CMUTs show some promise to balance the size and sensitivity [12], but they have limitations of high bias voltage, severe parasitic effects, and difficulties of fabricating narrow gaps. In contrast, pMUTs are more robust against parasitics [13], [14]. Several pMUTs have been presented for PAI applications [15]–[18]. However, commonly used AlN has relatively low piezoelectric coefficients [15], [16]. PZT has higher piezoelectric coefficients, but sputtered PZT or sol-gel PZT films suffer from high processing temperature, high stress, low deposition rate and small thickness [17], [18]. On the other hand, ceramic PZT is known to have over four times greater piezoelectric constants than thin-film PZT based on sol-gel or sputtering methods [19]. Using ceramic PZT can boost the piezoelectric response and lower the processing temperature, and ceramic PZT can be made in a wide range of thickness [20], [21], but ceramic PZT materials are fragile and seldom used in making MEMS devices because of the challenge of thinning ceramic PZT down to sub-10 μm.

In this work, a process of thinning ceramic PZT down to 4 μm has been developed and a 4 × 4 pMUT array based on thin ceramic PZT is demonstrated for endoscopic photoacoustic imaging applications.

II. Device Design and Fabrication

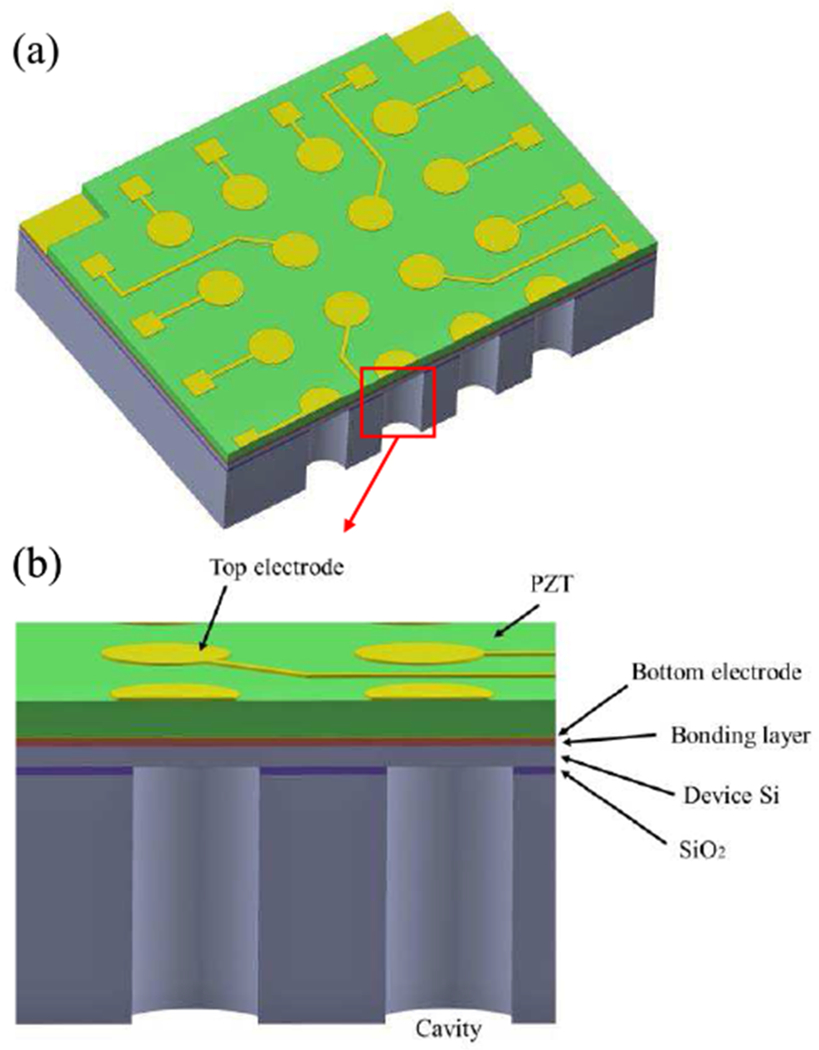

A 3D model of the designed 4 × 4 pMUT array is shown in Fig. 1(a) with a cross-sectional view shown in Fig. 1(b). Each pMUT element is composed of an Au/PZT/Au/PermiNex/Si multilayer membrane and an acoustic cavity. The whole structure is fabricated on a silicon on insulator (SOI) wafer. The device layer of the SOI functions as the supporting layer of the membrane. The pMUT works at the d31 mode of the piezoelectric layer via the flexural vibration of the thin membrane. A thin polymer layer (PermiNex 1000, MicroChem Inc., USA) is used to bond the ceramic PZT layer on the SOI substrate. The top and bottom electrodes both are made of sputtered Au and Cr.

Fig. 1.

3D model (a) and a cross-sectional view (b) of the designed pMUT array.

The fundamental resonance frequency of a pMUT is a key parameter for PAI applications as it largely determines the imaging resolution and depth. High spatial resolution can be achieved with high ultrasound frequency at the price of lower imaging depth due to the increased acoustic attenuation [22]. In this work, a resonance frequency of 1.5 MHz is selected as a balance of the resolution and penetration depth for the application in breast cancer imaging [23]. Since the pMUT can be modeled as a clamped circular multilayer vibration plate, its resonance frequency, f0, can be tuned with the thickness and diameter of the membrane based on the following relation [24]:

| (1) |

where a, D and ρ are the radius, equivalent flexural rigidity, and average area mass density of the membrane, respectively.

The parameters of the designed layer structure are listed in Table I. A ceramic PZT layer with a thickness of 4 μm is used in this work, and the diameter of the membrane is 210 μm, which are chosen to target at a resonant frequency of 1.5 MHz.

TABLE I.

Parameters of The Designed PMUT Layer Structure

| Layer name | Diameter (μm) | Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| Device silicon | 210 | 3 |

| PermiNex | 210 | 2 |

| Bottom electrode | 210 | 0.1 |

| PZT | 210 | 4 |

| Top electrode | 136 | 0.35 |

The critical step in the device fabrication is the thinning and integration process of ceramic PZT. In this work, by using wafer bonding and CMP process, a ceramic PZT with high piezoelectric constant was thinned down to about 4 μm and bonded on an SOI substrate successfully. Fig. 2 illustrates the fabrication process flow, which is a three-mask fabrication process starting from a commercial ceramic PZT wafer (PZT 5-H, CTS Inc., USA). To thin down the ceramic PZT, the PZT wafer is first temporarily bonded with a silicon wafer using a SU-8 photoresist and polished down to a thickness of 100 μm with a smooth surface (Fig. 2a). The polished PZT has a surface roughness Ra = 1.8 nm, which is small enough to ensure strong bonding strength. After that, Au and Cr is sputtered to form the bottom electrode. Next, PermiNex is spin coated on both the PZT wafer (Au/Cr side) and the SOI wafer as the adhesion layers, and then the two wafers are permanently bonded together (Fig. 2b) at a temperature of 180 °C, which is well below the Curie temperature (242 °C) of PZT-5H. Next, the PZT layer is further polished down to the desired thickness from the Si/SU-8 side by first completely removing the Si and SU-8 in sequence with a carefully tuned CMP process (Fig. 2c). The polished ceramic PZT is patterned to expose the bottom electrode by using a one-step residue-free wet etching recipe that is made of diluted fluoroboric acid (volume ratio HBF4:H2O = 1:10); the etching rate is around 1.5 μm/min at room temperature [25]. Then the top Au/Cr electrode is formed by sputtering and liftoff processes (Fig. 2d). Finally, the acoustic cavity is formed from the backside by DRIE and oxide etching using vapor HF (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Process flow of the ceramic PZT-based pMUT array fabrication.

III. Device Characterization

The top-view and backside SEM images of a fabricated pMUT array are shown in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), respectively. The pMUT array consists of 16 elements with a chip size of only 1.8 × 1.6 mm2. The opening and depth of the cavity of each pMUT element are 210 μm and 350 μm, respectively. Each pMUT element has its top electrode connected with a bonding pad and shares a common ground at four corners of the device. A cross-sectional SEM image of the thin membrane is shown in Fig. 3(c), where the thickness of the ceramic PZT is around 4 μm. Large grain sizes ranging from 2 to 3 μm were observed, which is expected and consistent with high piezoelectric constant of ceramic PZT [26].

Fig. 3.

SEM images of the fabricated pMUT array: (a) front side, (b) backside, and (c) cross section of the thin membrane.

The electrical impedance of the fabricated pMUT was measured in air and in water, respectively, with an impedance analyzer (4294 A, Agilent Inc., USA). The measured data are plotted in Fig. 4, showing a resonance frequency of 1.20 MHz and an anti-resonance frequency of 1.24 MHz in air and a resonance frequency of 0.8 MHz in water. The coupling coefficient is calculated as 6.3%. The reduced resonance frequency in water can be explained by the added radiation mass from the liquid as [27]:

| (2) |

where ffluid, fair, Ap, and Mp are the resonance frequencies in liquid and in air, the added mass, and the mass of the membrane, respectively. For the vibration of a clamped circular plate [28],

| (3) |

where ρfluid is the mass density of the fluid and a is the plate’s radius.

Fig. 4.

Measured impedances of the pMUT in air and water.

The acoustic sensing performance of the fabricated pMUT was evaluated in a mineral oil. Mineral oil and water are widely used coupling media in photoacoustic imaging studies due to their similar acoustic characteristics as those of human tissues [29]. In this experiment, a mineral oil was used because of its good electrical insulation property. Since pMUTs typically exhibit high electrical impedance, to pick up acoustic signals, a two-stage low-noise preamplifier circuit was made and the fabricated pMUT chip was directly glued on the circuit board and wire bonded. The whole chip was coated with a thin layer of Parylene C (~100 nm) as a protection layer before performing acoustic testing in the oil. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 5. One off-shelf immersion-type ultrasonic transducer (V303, Olympus Inc., USA) was used as an ultrasound transmitter, driven by a function generator. The pMUT worked as an ultrasound receiver with the output signal amplified by the low-noise preamplifier circuit and then captured by an oscilloscope.

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the experimental setup with a photo of pMUTs integrated on a preamp PCB.

The off-shelf ultrasonic transducer was driven by a pulse signal with a pulse width of 0.5 μs and an amplitude of 20 V. The transmitted acoustic signal was attenuated in mineral oil and picked up by the pMUT. Fig. 6 shows the pulse signal driving the transmitter and the signal detected at a distance of 3.7 cm by the pMUT. The frequency components of the pMUT signal were obtained using fast fourier transform (FFT), as shown in Fig. 7. The slight center frequency shift from 0.8 MHz in water to 0.83 MHz in the mineral oil is attributed to the smaller density of the mineral oil (0.87 g/cm3) than that of water (1 g/cm3). A −6 dB bandwidth (BW) of 183 KHz was achieved. the bandwidth can be further increased by patterning the piezoelectric layer into rib structures, which will reduce the membrane’s mass while enhancing its stiffness [30].

Fig. 6.

The pulse signal and the detected acoustic signal.

Fig. 7.

Frequency components of the pMUT signal.

IV. Photoacoustic Imaging

A photoacoustic imaging experiment was performed using the fabricated pMUT array in a tank filled with deionized water. Since the required volume of the coupling medium to submerge the imaging target and the pMUT array is large, deionized water, instead of mineral oil, is used in this experiment. A pencil lead with a diameter of 0.5 mm was embedded into an agar bar (3 cm in diameter and 6 cm in height) as the target to absorb optical energy and generate photoacoustic waves. the pencil lead was placed along the center axis of the bar. As shown in Fig. 8(a), short laser pulses (6 ns duration and 20 mj energy per pulse) generated from an OPO laser source (Phocus mobile, OPOtek inc., USA) with a wavelength of 720 nm were shone on the target, while the pMUT array was controlled by a rotation stage to scan around the target for acquisition of photoacoustic signals. Detected signals were amplified and then processed using an image reconstruction algorithm [31]. A photoacoustic image of the 0.5 mm pencil lead was successfully reconstructed, as shown in Fig. 8(b).

Fig. 8.

Photoacoustic imaging experiment: (a) photo of the experimental setup and (b) reconstructed photoacoustic image.

V. Conclusion

This paper presents the design, fabrication, and characterization of a ceramic PZT-based pMUT array. By using wafer bonding and CMP processes, ceramic PZT with high piezoelectric constant was successfully thinned down to 4 μm and integrated into the pMUT fabrication process. Compact 4 × 4 pMUT arrays with resonance frequency of around 1.2 MHz were fabricated and characterized. Photoacoustic imaging using a pencil lead embedded in an agar phantom was successfully demonstrated using the fabricated pMUT array. With a footprint of only 1.8 × 1.6 mm2, this pMUT array can be assembled into endoscopic probes with outer diameters less than 3 mm for in vivo early-cancer diagnosis and image-guided tumor surgery. This work shows the great potential of using ceramic PZT to fabricate high-sensitivity pMUTs for endoscopic photoacoustic imaging applications.

Acknowledgment

This work is sponsored by the National Institute of Health (NIH) under the award# R01EB020601.

Biographies

Haoran Wang received his B.E. degree in Measuring and Control Technology and Instruments from Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, in 2017. He is currently working toward a Ph.D. degree in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at University of Florida, Gainesville, USA. His research interests include microelectromechanical (MEMS) systems, micro/nano fabrication, and piezoelectric transducers.

Zhenfang Chen , founder of MEMS Engineering & Material which develops and manufactures SOI wafers and other bonded material for MEMS and semiconductor applications. Prior to this, he worked as the principle engineer for Fujifilm Dimatix, Santa Clara, California. He received Ph.D. in metallurgical physical chemistry from Central South University, Changsha, China.

Hao Yang received his B.E. and Ph.D. degree in optical engineering from Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, in 2010. He is currently working as a research professor in the Department of Medical Engineering at University of South Florida, Tampa, USA. His research interests include optical-based imaging technologies for in vivo visualization of tissue at both the macroscopic and microscopic scales.

Huabei Jiang , PhD, started his career as an Assistant Professor of physics at Clemson University in 1997, and became a full Professor there in 2003. He then joined University of Florida (UF) in 2005 as a founding senior faculty of then newly established biomedical engineering department and became the J. Crayton Pruitt Family endowed professor in 2008 at UF. Dr. Jiang joined University of South Florida (USF) in 2017 as a founding faculty of medical engineering department and the founding Director of USF Center for Advanced Biomedical Imaging. Professor Jiang has published over 400 peer-reviewed scientific articles and patents. He is also the author of three books, Diffuse Optical Tomography: Principles and Applications (CRC Press, 2010), Photoacoustic Tomography (CRC Press, 2014), and Thermoacoustic Tomography: Principles and Applications (IOP Publishing, 2020). Huabei Jiang is a Fellow of the Optical Society of America (OSA), a Fellow of the International Society of Optical Engineering (SPIE), and a Fellow of the American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering (AIMBE). Outside his research/teaching, Huabei Jiang spends much of his time practicing Chinese Calligraphy and painting (ink/color pencil and watercolor). He has had the first exhibition of his artworks in July 2019 in Chengdu, China.

Huikai Xie (S’00-M’02-SM’07-F’17) received his B.S., M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in electrical and computer engineering from Beijing Institute of Technology, Tufts University and Carnegie Mellon University, respectively. He joined the University of Florida in 2002 as an assistant professor, where he is currently a professor at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. He also worked at Tsinghua University as a researcher, Robert Bosch Company as a summer intern, and US Air Force Research Lab as a summer faculty fellow. His research interests include MEMS/NEMS, integrated sensors, microactuators, integrated power passives, CNT-CMOS integration, optical MEMS, LiDAR, micro-spectrometers, optical bioimaging, and endomicroscopy. He is an associate editor of IEEE Sensors Letters, and Sensors & Actuators A. He has published over 300 technical papers and holds more than 30 patents. He is a fellow of IEEE and SPIE.

Contributor Information

Haoran Wang, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 USA.

Zhenfang Chen, MEMS Engineering and Materials Inc., Sunnyvale, CA 94087 USA.

Hao Yang, Department of Medical Engineering, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620 USA.

Huabei Jiang, Department of Medical Engineering, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620 USA.

Huikai Xie, School of Information and Electronics, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China.

References

- [1].Wang X, Pang Y, Ku G, Xie X, Stoica G, and Wang L, “Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain,” Nat. Biotechnol, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 803–806, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ermilov SA et al. “Laser optoacoustic imaging system for detection of breast cancer,” J. Biomed. Opt, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 024007, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Xi L, and Jiang H, “High resolution three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging of human finger joints in vivo,” Appl. Phys. Lett, vol. 107, pp. 063701, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lin L et al. “Single-breath-hold photoacoustic computed tomography of the breast,” Nat. Commun, vol. 9, pp. 2352, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ku G, Wang X, Stoica G, and Wang LV, “Multiple-bandwidth photoacoustic tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 49, pp. 1329–1338, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang Q et al. “Non-invasive imaging of epileptic seizures in vivo using photoacoustic tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 53, pp. 1921–1931, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yuan Y, Yang S, and Xing D, “Preclinical photoacoustic imaging endoscope based on acousto-optic coaxil system using ring transducer array,” Opt. Lett, vol. 35, no. 13, pp. 2266–2268, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xi L et al. “Evaluation of breast tumor margins in vivo with intraoperative photoacoustic imaging,” Opt. Express, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 8726–8731, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang J, Li C, Chen R, Zhou Q, Shung KK, and Wang LV, “Catheter-based photoacoustic endoscope,” J. Biomed. Opt, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 066001, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang J, Maslov K, Yang H, Zhou Q, Shung KK, and Wang LV, “Photoacoustic endoscopy,” Opt. Lett, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 1591–1593, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Basij M et al. “Miniaturized phased-array ultrasound and photoacoustic endoscopic imaging system,” Photoacoustics, vol. 15, pp. 100139, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vaithilingam S et al. “Three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging using a two-dimensional CMUT array,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 2411–2419, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Qiu Y et al. “Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducer (PMUT) arrays for integrated sensing, actuation and imaging,” Sensors, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 8020–8041, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jung J, Lee W, Kang W, Shin E, Ryu J, and Choi H, “Review of piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers and their applications,” J. Micromech. Microeng, vol. 27, pp. 113001, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen B, Chu F, Liu X, Li Y, Rong J, and Jiang H, “AlN-based piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer for photoacoustic imaging,” Appl Phys. Lett, vol. 103, pp. 031118, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dangi A et al. “Ring PMUT array based miniaturized photoacoustic endoscopy device,” Proceedings of Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing, 2019, pp. 1087811. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dangi A et al. “Evaluation of high frequency piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducers for photoacoustic imaging,” IEEE Sensors, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liao W et al. “Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducer array for photoacoustic imaging,” Transducers, 2013, pp. 1831–1834. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aktakka EE, Aktakka EE, Peterson RL, and Najafi K, “Wafer-level integration of high-quality bulk piezoelectric ceramics on silicon,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 2022–2030, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hindrichsen CG, Lou-Møller R, Hansen K, and Thomsen EV, “Advantages of PZT thick film for MEMS sensors,” Sens. Actuators A Phys, vol. 163, pp. 9–14, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang H, Yu Y, Chen Z, Yang H, Jiang H, and Xie H, “Design and fabrication of a piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer array based on ceramic PZT,” IEEE Sensors, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zackrisson S, van de Ven SMWY, and Gambhir SS, “Light in and sound out: emerging translational strategies for photoacoustic imaging,” Cancer Research, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 979–1004, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xi L, Li X, Yao L, Grobmyer S, and Jiang H, “Design and evaluation of a hybrid photoacoustic tomography and diffuse optical tomography system for breast cancer detection,” Med. Phys, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 2584–2594, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lu Y and Horsley DA, “Modeling, fabrication, and characterization of piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer arrays based on cavity SOI wafers,” J. Microelectromech. Syst, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 1142–1149, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang H, Godara M, Chen Z, and Xie H, “A one-step residue-free wet etching process of ceramic PZT for piezoelectric transducers,” Sens. Actuators A Phys, vol. 290, pp. 130–136, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Randall CA, Kim N, Kucera J, Cao W, and Shrout TR, “Intrinsic and extrinsic size effects in fine-grained morphotropic-phase-boundary lead zirconate titanate ceramics,” J. Am. Ceram. Soc, vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 677–688, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lu Y, Heidari A, and Horsley DA, “A high fill-factor annular array of high frequency piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers,” J. Microelectromech. Syst, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 904–913, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Blevins RD, Formulas for Natural Frequency and Mode Shape, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liang S, Lashkari B, Choi S, Ntziachristos V, and Mandelis A, “The application of frequency-domain photoacoustics to temperature-dependent measurements of the Grüneisen parameter in lipids,” Photoacoustics, vol. 11, pp. 56–64, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rozen O, Shelton SE, Guedes A, and Horsley DA, “Variable thickness diaphragm for a stress insensitive wideband piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer,” in Proc. Solid-State Sens., Actuators Microsyst. Workshop. Hilton Head, SC, USA, June. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hoelen CGA, and de Mul FFM, “Image reconstruction for photoacoustic scanning of tissue structures,” Appl. Opt, vol. 39, no. 31, pp. 5872–5883, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]