Abstract

Objective

To identify factors that contribute to missed cataract surgery follow-up visits, with an emphasis on socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, patients who underwent cataract extraction by phacoemulsification at Massachusetts Eye and Ear between 1 January and 31 December 2014 were reviewed. Second eye cases, remote and international patients, patients with foreign insurance and combined cataract cases were excluded.

Results

A total of 1931 cases were reviewed and 1089 cases, corresponding to 3267 scheduled postoperative visits, were included. Of these visits, 157 (4.8%) were missed. Three (0.3%) postoperative day 1, 40 (3.7%) postoperative week 1 and 114 (10.5%) postoperative month 1 visits were missed. Age<30 years (adjusted OR (aOR)=8.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 35.2) and ≥90 years (aOR=5.7, 95% CI 2.0 to 15.6) compared with patients aged 70–79 years, estimated travel time of >2 hours (aOR=3.2, 95% CI 1.4 to 7.4), smokers (aOR=2.7, 95% CI 1.6 to 4.8) and complications identified up to the postoperative visit (aOR=1.4, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.1) predicted a higher rate of missed visits. Ocular comorbidities (aOR=0.7, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0) and previous visit best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/50–20/80 (aOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.7) and 20/90–20/200 (aOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9), compared with BCVA at the previous visit of 20/40 or better, predicted a lower rate of missed visits. Gender, race/ethnicity, language, education, income, insurance, alcohol use and season of the year were not associated with missed visits.

Conclusions

Medical factors and demographic characteristics, including patient age and distance from the hospital, are associated with missed follow-up visits in cataract surgery. Additional studies are needed to identify disparities in cataract postoperative care that are population-specific. This information can contribute to the implementation of policies and interventions for addressing them.

Keywords: ophthalmology, cataract and refractive surgery, health services administration & management, organisation of health services, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Variables that vary over time were assessed using a visit-based generalised estimated equation analysis.

Data collection and recording were performed manually by trained research staff.

Retrospective study design.

Single-centre study.

Introduction

Cataract extraction is the most commonly performed surgical procedure in the USA and the single largest expenditure of Medicare surgical procedures, accounting for approximately three million cases performed annually.1 The number of people with cataracts in the USA is forecasted to increase from the current estimation of approximately 25.7–45.6 million by 2050.1

The month following cataract surgery is the time when most complications occur and when stable vision is achieved.2 While the frequency of cataract surgery follow-up examinations varies, most patients are seen one to three times for planned postoperative evaluations to ensure the eye is healing, to assess compliance with postoperative instructions and medications, and to identify and treat complications if they arise.2 Missed postoperative visits have been associated with higher risk of non-detection of complications and disease in outpatient eye care.3–5 While many cataract postoperative complications are symptomatic, certain postoperative sequelae, such as intraocular pressure elevation, can often go unnoticed and refractive errors can remain uncorrected unless the patient is evaluated.6–9 Moreover, missed visits result in underuse of clinical and administrative resources and lead to decreased clinical efficiency with potential concomitant revenue loss.10 11

Reports have identified gender, racial and socioeconomic disparities in the use of eye care services.12–14 Understanding the disparities in care underlying missed postoperative visits is a first step in targeting interventions to increase follow-up compliance in these populations. However, studies estimating the rate and exploring the reasons of patient non-attendance following cataract surgery have been limited.

In a large series from India, Gupta et al investigated predictors of compliance with cataract surgery follow-up.15 However, that centre practised a follow-up pattern in which some patients were admitted to the hospital for 1–7 days, and socioeconomic factors were not studied. Two prior studies have small patient samples,16 17 included surgical cases performed by trainees only,16 17 evaluated non-attendance at a late (≥3 months) postoperative timepoint16 or focused on an indigent, rural population.16 A comprehensive analysis of no-shows following cataract surgery in the USA is lacking.

In this study, we sought to identify demographic, socioeconomic and medical factors that predict missed cataract surgery follow-up visits in an academic practice in the USA, with an emphasis on identifying healthcare disparities.

Methods

Study population

Patient data were extracted from the Perioperative Care for Intraocular Lens database, which incorporates perioperative data of patients who underwent cataract extraction by phacoemulsification at Massachusetts Eye and Ear between 1 January and 31 December 2014. All cases were performed by 10 comprehensive ophthalmologists. Cases for chart review were identified using Classification of Procedural Terminology codes 66 982 (extracapsular cataract extraction with intraocular lens insertion, complex) and 66 984 (extracapsular cataract extraction with intraocular lens insertion).

Missed visits

Cataract surgeons who participated in our study routinely schedule three postoperative visits for all patients, at day 1, week 1 and month 1 after surgery. A visit was considered ‘missed’ if the patient did not attend a scheduled postoperative day 1 (POD1) appointment within 2 days, postoperative week 1 (POW1) appointment between days 5 and 14, or postoperative month 1 (POM1) appointment between weeks 3 and 8 from surgery. If an emergency visit for any reason followed an unattended appointment within the aforementioned time intervals, the visit was considered ‘attended’.

Automated phone calls 3 days prior to each appointment were delivered using the TeleVox electronic system (Mobile, Alabama, USA). No additional reminders were sent to patients who missed one or more follow-up visits.

Data

Review of the electronic medical records and data collection were conducted by four trained study personnel. We evaluated variables that were found to be associated with missed visits in ophthalmology and other clinical settings and were thought to be relevant in cataract surgery.15–23 Age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary language, level of education, insurance type, ocular comorbidities, season of the year and primary surgeon variables were categorised based on clinical relevance. Estimated travel time (ETT) to the location of the scheduled visit was determined using zip codes and the Google Maps web service set on a fixed date and time.24 The driving module and the attending surgeon’s practice location were selected for navigation. Average adjusted gross income by zip code was estimated after reviewing the 2014 income statistics published by the Internal Revenue Service.25 For smoking and alcohol use, the definitions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Health Interview Survey (‘never smoker’, ‘current smoker’ and ‘former smoker’)26 and drinking patterns described by the National Institutes of Health (‘no drinking’, ‘low-risk drinking’ and ‘high-risk drinking)27 were adopted, respectively. If case categorisation was equivocal, values were assigned as missing.

Snellen best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) measurements and complications were recorded for each encounter. In order to assess the association of visual outcomes with missed visits, we analysed BCVA at the previous visit, which represents the most recent recording prior to each appointment. Preoperative day 1 and week 1 BCVA recordings were used for POD1, POW1 and POM1 visits, respectively. For complications, we created a binary (‘yes’ or ‘no’) variable ‘complications up to the prior visit’, which indicates the occurrence of intraoperative and/or postoperative complications at a preceding postoperative visit. A patient was considered to have experienced an intraoperative complication if at least one of the following had occurred during surgery: posterior capsule tear, anterior capsule rent, zonular dehiscence, lens fragments dropped into the vitreous and placement of the intraocular lens into the anterior chamber or sulcus. A patient was defined as having a postoperative complication if at least one of the following was noted at a postoperative visit: intraocular pressure measurement above 21 mm Hg, anterior chamber paracentesis, displaced intraocular lens, wound leak, severe corneal oedema, epithelial defect or retained lens fragment.

Exclusion criteria

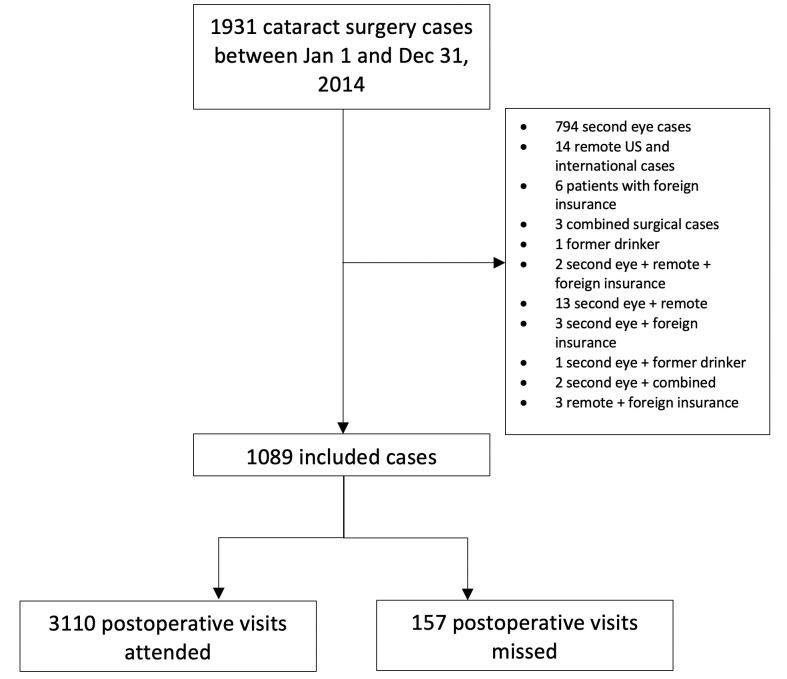

The following cases were excluded (1) second eye cases; (2) patients with a declared place of residence outside the broader area of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York, including international patients; (3) patients owning foreign insurance; (4) cataract cases combined with vitreoretinal or glaucoma surgery; and (5) former drinkers, due to the small number. A flowchart of selected cases is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of case selection and outcomes. Some cases were excluded for more than one reason.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using STATA V.15. In order to assess time-varying and visit-specific variables, such as ‘BCVA at prior visit’, complications up to the prior visit and ‘season of the year for each visit’, we stratified patient clusters to single-visit observations. Unadjusted associations between predictors and the binary ‘missed visits’ outcome were estimated using generalised estimated equation (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation matrix while accounting for between-visit correlations. Variables associated with missed visits with a p value of <0.1 were entered in a multivariable GEE model in order to identify independent predictors for missed visits and to estimate the adjusted associations.

Missing data that were hypothesised to be associated with the outcome variable (eg, unreported data on race/ethnicity and education level) were analysed as an additional category. Values that were thought to be missing at random were deleted in a listwise fashion. The α level of significance was set at 0.05 and p values were two-sided.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Out of 1931 cataract cases reviewed, a total of 1089 cases were included (figure 1). The mean patient age was 63.5 years (SD 11.1 years). Four hundred and sixty-eight (43.0%) were men and the majority, 788 (72.4%), were white patients. One hundred and forty-one (12.9%) cases missed at least one postoperative visit: 128 (11.8%) patients did not attend one postoperative visit; 10 (0.9%) patients did not attend two postoperative visits; and 3 (0.3%) patients did not attend all three postoperative visits. Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of included cases.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cataract patients

| n (%) or mean±SD† | |

| Age group (years) | 63.5±11.1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 468 (43.0) |

| Female | 621 (57.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 788 (72.4) |

| Black/African–American | 91 (8.4) |

| Hispanic | 42 (3.9) |

| Asian | 54 (5.0) |

| Other/NR* | 114 (10.5) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 867 (79.6) |

| Other | 102 (9.4) |

| Missing | 120 (11.0) |

| Highest education level | |

| High school or lower | 211 (19.4) |

| College or higher | 372 (34.2) |

| NR* | 506 (46.5) |

| Adjusted gross income | |

| <$50 000 | 433 (39.8) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 469 (43.1) |

| ≥$75 000 | 185 (17.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) |

| Insurance | |

| Commercial | 649 (59.6) |

| Public | 307 (28.2) |

| Commercial and public | 109 (10.0) |

| Self-pay | 20 (1.8) |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) |

| Estimated travel time (min) | |

| ≤120 | 1065 (97.8) |

| ≥121 | 22 (2.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | 889 (81.6) |

| Current smoker | 67 (6.2) |

| Former smoker | 131 (12.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) |

| Alcohol use | |

| No drinking | 598 (54.9) |

| Low-risk drinking | 443 (40.7) |

| High-risk drinking | 46 (4.2) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) |

| Ocular comorbidities | |

| No | 624 (57.3) |

| Yes | 465 (42.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary surgeon | |

| Attending | 799 (73.4) |

| Resident | 283 (26.0) |

| Missing | 7 (0.6) |

| Missed visits | |

| No | 948 (87.1) |

| Yes | 141 (12.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

*Missing data in race/ethnicity and highest education level were analysed as a distinct category.

†Percentages may not add up to 100%.

NR, not reported.

Of the 3267 postoperative visits analysed, 3110 (95.2%) were attended and 157 (4.8%) were missed. Three (0.3% of POD1 visits) POD1, 40 (3.7% of POW1 visits) POW1 and 114 (10.5% of POM1 visits) POM1 visits were missed. Table 2 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of included cases at each visit by follow-up status.

Table 2.

GEE bivariate and multivariable analyses of potential predictors of missed follow-up visits after cataract surgery

| Total visits (n) | Missed visits, n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value* | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 12 | 3 (25.0) | 7.4 (1.7 to 31.4) | 0.007† | 8.2 (1.9 to 35.2) | 0.005† |

| 30–39 | 21 | 1 (4.8) | 1.1 (0.1 to 9.9) | 0.93 | 1.4 (0.2 to 12.1) | 0.78 |

| 40–49 | 141 | 6 (4.3) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.5) | 0.98 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.3) | 0.82 |

| 50–59 | 465 | 26 (5.6) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) | 0.31 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | 0.56 |

| 60–69 | 1071 | 45 (4.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) | 0.91 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.49 |

| 70–79 | 1137 | 49 (4.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 80–89 | 381 | 21 (5.5) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 0.37 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | 0.24 |

| ≥90 | 39 | 6 (15.4) | 4.0 (1.5 to 10.8) | 0.006† | 5.7 (2.0 to 15.6) | 0.001† |

| Missing | 0 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Gender | – | – | ||||

| Male | 1404 | 67 (4.8) | Ref | |||

| Female | 1863 | 90 (4.8) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 0.94 | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – | ||

| Race/ethnicity | – | – | ||||

| White | 2364 | 111 (4.7) | Ref | |||

| Black/African–American | 273 | 16 (5.9) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 0.43 | ||

| Hispanic | 126 | 6 (4.8) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.5) | 0.97 | ||

| Asian | 162 | 7 (4.3) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | 0.84 | ||

| Other/NR‡ | 342 | 17 (5.0) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 0.83 | ||

| Primary language | – | – | ||||

| English | 2601 | 125 (4.8) | Ref | |||

| Other | 306 | 15 (4.9) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.95 | ||

| Missing | 360 | 17 (4.7) | – | – | ||

| Highest education level | – | – | ||||

| High school or lower | 633 | 32 (5.1) | Ref | |||

| College or higher | 1116 | 44 (4.0) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.3 | ||

| NR‡ | 1518 | 81 (5.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 0.8 | ||

| Adjusted gross income | ||||||

| <$50 000 | 1299 | 71 (5.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| $50 000–$74 999 | 1407 | 68 (4.8) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 0.54 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 0.57 |

| ≥$75 000 | 555 | 18 (3.2) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0§) | 0.07 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.21 |

| Missing | 6 | 1 (16.7) | – | – | – | – |

| Insurance | – | – | ||||

| Commercial | 1947 | 83 (4.3) | Ref | |||

| Public | 921 | 52 (5.7) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | 0.13 | ||

| Commercial and public | 327 | 19 (5.8) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.25 | ||

| Self-pay | 60 | 3 (5.0) | 1.2 (0.3 to 4.2) | 0.8 | ||

| Missing | 12 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | ||

| Estimated travel time (min) | ||||||

| ≤120 | 3195 | 149 (4.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥121 | 66 | 8 (12.1) | 2.8 (1.3 to 6.4) | 0.012† | 3.2 (1.4 to 7.4) | 0.006† |

| Missing | 6 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | 2676 | 119 (4.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Current smoker | 192 | 20 (10.4) | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.2) | 0.001† | 2.7 (1.6 to 4.8) | 0.0004† |

| Former smoker | 393 | 18 (4.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.91 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 0.71 |

| Missing | 6 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Alcohol use | – | – | ||||

| No drinking | 1794 | 84 (4.7) | Ref | |||

| Low-risk drinking | 1329 | 62 (4.7) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 0.98 | ||

| High-risk drinking | 138 | 11 (8.0) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.6) | 0.11 | ||

| Missing | 6 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | ||

| Ocular comorbidities | ||||||

| No | 1872 | 105 (5.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1395 | 52 (3.7) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.022† | 0.7 (0.5-1.0¶) | 0.05† |

| Missing | 0 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Complications up to prior encounter | ||||||

| No | 2519 | 112 (4.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 748 | 45 (6.0) | 1.5 (1.0§ to 2.1) | 0.026† | 1.4 (1.0§ to 2.1) | 0.05† |

| Missing | 0 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| BCVA at prior encounter | ||||||

| 20/40 or better | 1683 | 98 (5.8) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 20/50–20/80 | 973 | 27 (2.8) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.7) | <0.0001† | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.7) | 0.0003† |

| 20/90–20/200 | 276 | 8 (2.9) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.028† | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.026† |

| 20/210 or worse | 335 | 24 (7.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.97 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | 0.92 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Season | – | – | ||||

| Winter | 783 | 40 (5.1) | Ref | |||

| Spring | 874 | 39 (4.5) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.57 | ||

| Summer | 713 | 38 (5.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | 0.89 | ||

| Autumn | 879 | 38 (4.3) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.53 | ||

| Missing | 18 | 2 (11.1) | – | – | ||

| Primary surgeon | – | – | ||||

| Attending | 2397 | 109 (4.6) | Ref | |||

| Resident | 849 | 46 (5.4) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | 0.34 | ||

| Missing | 21 | 2 (9.5) | – | – | ||

*P value derived by bivariate or multivariable GEE analysis is testing whether there is a significant difference in the rate of missed visits for each candidate predictor category compared with the reference category.

†Statistically significant.

‡Missing data in race/ethnicity and highest education level were analysed as a distinct category.

§CI limit>1.0.

¶CI limit<1.0.

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; GEE, generalised estimated equation; NR, not reported; ref, reference.

Predictors

Groups that were significantly associated with missed visits in the bivariate analysis were patient age <30 years (unadjusted OR (uOR)=7.4, 95% CI 1.7 to 31.4) and ≥90 years (uOR=4.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 10.8) compared with patients aged 70–79 years, ETT of >2 hours (uOR=2.8, 95% CI 1.3 to 6.4), current smokers compared with those who had never smoked (uOR=2.5, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.2) and the occurrence of complications during surgery or at a previous postoperative visit (uOR=1.5, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.1). A history of ocular comorbidities (uOR=0.7, 95% CI 0.5 to 0.9) and patients with BCVA at the previous visit 20/50–20/80 (uOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.7) and 20/90–20/200 (uOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9), compared with patients with prior-visit BCVA 20/40 or better, were associated with a lower rate of missed visits in the bivariate analysis. Gender, race/ethnicity, primary language, education level, adjusted gross income, insurance type, drinking status, season of the year and primary surgeon type were not associated with missed visits in the bivariate analysis. Table 2 shows the bivariate associations of candidate predictors with missed visits.

The aforementioned significantly associated variables were included in the multivariable analysis. Adjusted gross income was also modelled as the p value was less than 0.1 for the ≥$75 000 category. Groups that were significantly associated with missed visits in the multivariable analysis were age <30 years (adjusted OR (aOR)=8.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 35.2) and ≥90 years (aOR=5.7, 95% CI 2.0 to 15.6) compared with patients aged 70–79 years, ETT of >2 hours (aOR=3.2, 95% CI 1.4 to 7.4), current smokers compared with those who had never smoked (aOR=2.7, 95% CI 1.6 to 4.8) and the occurrence of complications during surgery or at a previous postoperative visit (aOR=1.4, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.1). A history of ocular comorbidities (aOR=0.7, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0) and patients with previous visit BCVA 20/50–20/80 (aOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.7) and 20/90–20/200 (aOR=0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9), compared with patients with BCVA at the previous visit 20/40 or better, were associated with a lower rate of missed visits in the multivariable analysis. Adjusted gross income did not independently predict the incidence of missed visits. Table 2 shows the multivariable analysis of missed visits predictors.

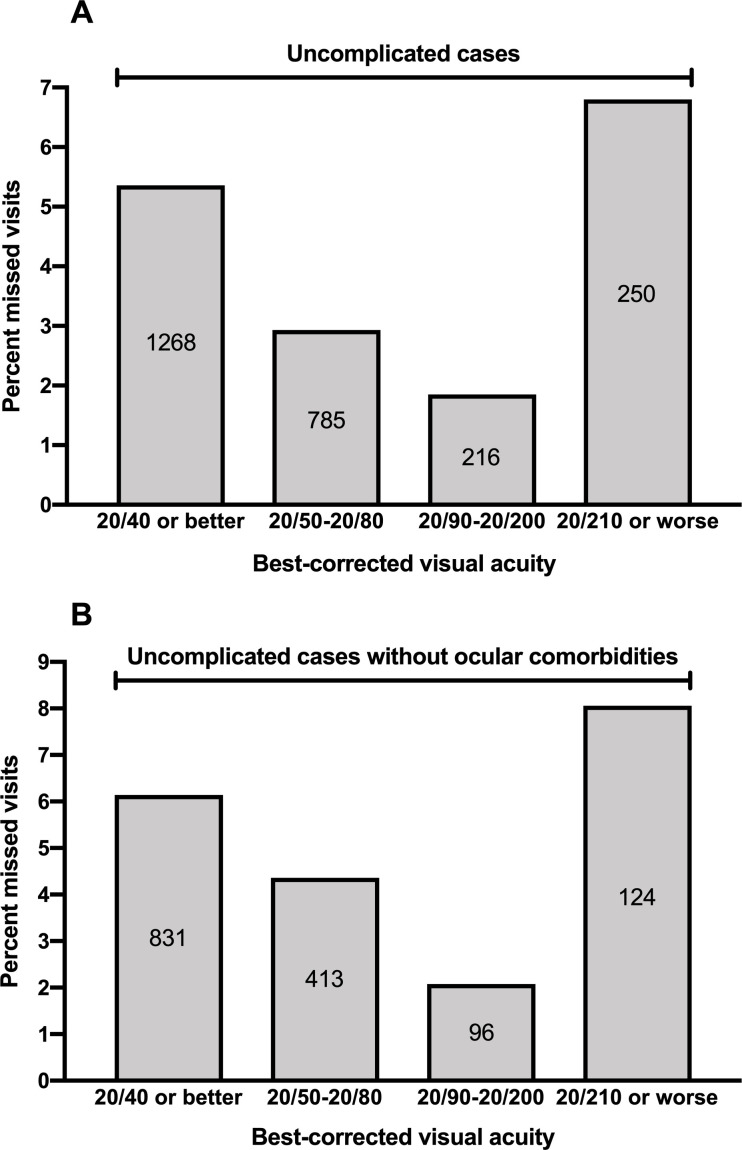

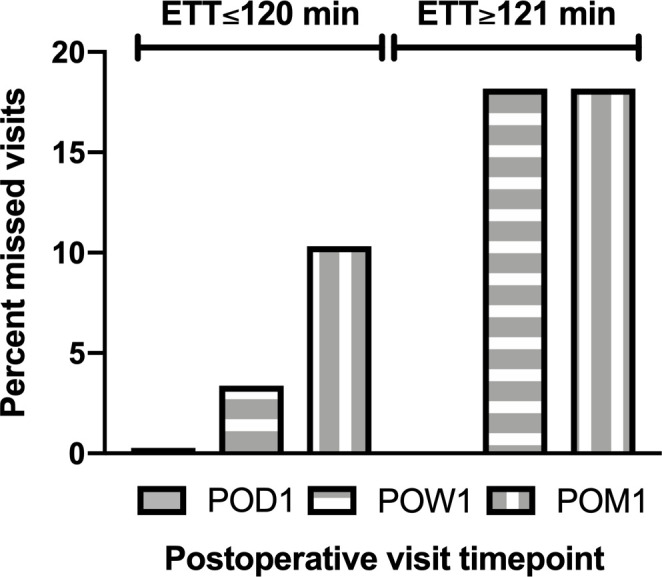

Figure 2 illustrates the joint effect of ETT and the postoperative visit timepoint. In our cohort, 0.3% of POD1, 3.4% of POW1 and 10.3% of POM1 visits were missed in patients who had to travel ≤2 hours to the clinic. For patients who had to travel >2 hours, none of POD1, 18.2% of POW1 and 18.2% of POM1 visits were missed. Figure 3 shows the joint effect of prior-visit BCVA, complications and ocular comorbidities. The percentage of missed visits decreased with worsening BCVA categories when controlling for both complications alone and complications in conjunction with ocular comorbidities. Patients with BCVA of 20/210 or worse demonstrated the highest risk for missed visits, and the pattern was maintained even when controlling for complications and ocular comorbidities.

Figure 2.

Percentage of missed follow-up visits at each postoperative timepoint after cataract surgery stratified by ETT category. ETT, estimated travel time; POD1, postoperative day 1; POM1, postoperative month 1; POW1, postoperative week 1.

Figure 3.

Percentage of missed follow-up visits of (A) uncomplicated cases and (B) uncomplicated cases without history of ocular comorbidities stratified by best-corrected visual acuity category.

Discussion

This study explored risk factors for missed follow-up visits after cataract surgery in a US tertiary academic centre and identified demographic healthcare disparities that are associated with patient non-attendance, including patient age and distance from the clinic.

The no-show rate of postoperative visits in this study was lower than the reported rate in other studies, which commonly reaches over 20%.16 17 20 21 28 29 In our study, 4.8% of postoperative appointments were unattended and 12.8% of patients missed at least one follow-up visit. The improved compliance with scheduled postoperative care demonstrated in this study is likely multifactorial and can be attributed to the short driving distances and the public transportation in Boston, the increased medical awareness of the population as a whole, the reminder system used in our department, and the emphasis of our physicians and staff on the importance of follow-up attendance, especially on the first postoperative day. The no-show rate of patients who underwent cataract surgery in India (14.4%) was similar to that measured in this study, showing that factors pertaining to the geographical region and institution significantly affect patient behaviour.15

The POM1 visit was the highest risk for non-attendance followed by the POW1 visit. This is consistent with other studies concluding that long lead time from scheduling to appointment increases the risk of missing a visit.20 23 30 31 Patients are less able to plan effectively long-term,16 and are more likely to forget or seek care elsewhere.32 Moreover, as vision improves and complaints such as eye discomfort and redness are diminished, a postoperative visit is more likely to be perceived as unnecessary.32

Gupta et al found a linear association of visual acuity and follow-up compliance, with patients having better visual outcomes demonstrating more adherence.15 On the contrary, in our cohort, better visual acuity at the previous visit was associated with a higher rate of subsequent missed appointments, except for patients with very low vision who exhibited the highest rate of non-attendance, even after controlling for confounders. This difference may be explained by the fact that we specifically studied visual acuity at the most recent visit, while Gupta et al used preoperative/discharge visual acuity.15 Although we cannot explain this finding in our study with certainty, we hypothesise that the low-vision group represented frustrated patients who possibly sought care at another provider. Similarly, complicated cases were less adherent to follow-up in our study. This is in agreement with Gupta et al,15 again possibly indicating patient frustration and switch of healthcare provider.

Very young and very old patients demonstrated significantly higher risk for missed appointments, in accordance with other studies.10 21 22 33–39 Young patients may be more indifferent about their health or may find it difficult to take time off work and off family duties.22 39 Older patients are at greater risk for medical comorbidities, ambulatory difficulties and cognitive impairment, often making them dependent on a companion for medical visits.40 41 More than one-third of the US population aged 65 years and older report some type of disability, including walking problems and independent living difficulties.42 Barriers to healthcare for those individuals may also be practice-related. In a telephone survey, 22% of subspecialty practices in four US cities reported inability to accommodate patients with mobility impairment due to physical barriers and inaccessibility.43

Given that multiple postoperative encounters are usually recommended after cataract surgery, distance to the clinic and accessibility of transportation may significantly influence patient willingness and ability to show up.13 44 In our cohort, the likelihood of missed appointments increased with longer times required to get to the clinic. The difference was especially notable for patients who had to travel >2 hours compared with patients who needed a 2-hour trip or less. The former group was largely represented by patients living in nearby counties and the suburbs, for whom a trip to Boston may seem more time-consuming and logistically challenging. Other studies have shown that residents in rural areas are less likely to use eye care services compared with urban residents.45 The CDC reported lower access to eye care in states with long travel distances, such as Missouri, New Mexico, Colorado and Indiana.46 Orr et al found that having the ability to drive increased the odds of visiting an ophthalmologist compared with non-drivers.18 However, patients with vision problems are more likely to have discontinued driving, creating barriers to visiting the doctor’s office, especially in areas with poor public transportation systems.47

Although many studies have identified socioeconomic disparities in the use of eye care and the receipt of cataract surgery,13 19 21 33 48 49 factors such as race/ethnicity, language, income, insurance and education level did not predict missed visits in our cohort. In the study by Chou et al examining how socioeconomic indices affect access to eye examinations, Massachusetts demonstrated a higher rate of eye exams in Hispanics, less educated individuals and low-income people.19 These observations were attributed to the expansion of MassHealth, the combined state Medicaid programme, and the near-universal health coverage resulting from the 2006 Massachusetts healthcare reform, which provided free or subsidised insurance to residents earning less than the federal poverty level.19 50 More studies are needed in order to clarify whether our observations are state-specific or apply to other regions as well.

Given the dynamic structure of healthcare systems and the variability of determinants for access, addressing disparities in healthcare can be a challenging task. The study of disparities in different areas of healthcare is fundamental for developing effective strategies at the public level. The implementation of access standards dictating the mandated travel time to the clinic, the time frame within which appointments must be scheduled and the minimum number of providers relative to the population have shown mixed results in primary and specialty care.51 However, policy implementation has been more effective in improving access and reducing inequalities.51 These policies need to be consistently updated and adjusted driven by state-specific needs.52 Also, with ongoing advances in teleophthalmology, telecommunication techniques, such as virtual encounters and the acquisition of ocular images, may be considered for cataract patients who are at high risk for non-attendance. This could include patients needing to travel >2 hours to the clinic, the very young and the elderly.53

This study represents the first comprehensive documentation of factors that predict no-shows at cataract surgery follow-up in the USA and the first to investigate the effect of socioeconomic factors on cataract postoperative care. Furthermore, by performing a visit-based analysis, we were able to accurately assess the effect of visual acuity and complications, variables that are indirectly evaluated in other studies.

Limitations of the study are its retrospective design (retrospective data acquisition and missing data) and the fact that participants were recruited from a single institution. Thus, results may not be generalisable to centres with different follow-up patterns and geographical areas with disparate socioeconomic background and transportation systems. Although we recruited a substantial number of cataract cases, a larger sample size would allow for more accurate estimation of the odds of missed visits in unusual patients, such as the very young ones (wide CI may indicate a labile association), as well as further subgroup and joint-effect analyses. Lastly, patient financial status in our study was based on residential data; therefore, the risk of ecological fallacy cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, this study identified factors that predict missed follow-up visits after cataract surgery in a tertiary US hospital. Studies in other regions will help to evaluate the rates and reasons for non-compliance at a national level. These results inform inequalities in cataract surgery postoperative care and provide a tool to cataract surgeons and health planners for identification of patients that are high risk for non-attendance, thereby forming a basis for more effective scheduling at the practice level. Targeted interventions have the potential to avoid interruptions in healthcare delivery and to ensure even receipt of cataract care at the community level.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: The PCIOL Study Group members: Sheila Borboli-Gerogiannis, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Stacey Brauner, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); H. Peggy Chang, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Kenneth Chang, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Sherleen H. Chen, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Matthew Gardiner, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Scott H. Greenstein, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Carolyn E. Kloek, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, Dean McGee Eye Institute, University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, Oklahoma City, OK, USA); Ann-Marie Lobo, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA); Z. Katie Luo, MD, PhD (Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA)

Contributors: GAM conceptualised the study, searched the literature, analysed the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript; DSB collected and recorded the data, revised the manuscript and earned funding for the study; EAE and NK collected and recorded the data and revised the manuscript; CEK conceptualised the study, revised the manuscript, earned funding for the study and supervised the whole work; the Perioperative Care for Intraocular Lens Study Group collected the data and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons, Fairfax, VA, USA (DSB and CEK). The funding sources and organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this retrospective cohort study, including patient data review. A waiver of patient consent was granted, given the retrospective nature of the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Raw data underlying the study cannot be made publicly available due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board (IRB). Upon request, deidentified data will be shared along with any information necessary to interpret the data, such as study protocols, data instruments and survey tools. Prior to that, the detailed plan to execute these methods must be reviewed and approved by the IRB, according to the Partners Healthcare policy. We will ensure long-term data storage and availability by consistently renewing our IRB protocol and by maintaining electronic files of the dataset in more than one encrypted computers/USB devices and in the Massachusetts Eye and Ear file hosting service. Researchers interested in the data may contact any of the authors as follows: Giannis Moustafa, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, telephone number: (617) 523-7900, email: giannis_moustafa@meei.harvard.edu; Durga Borkar, Wills Eye Hospital, telephone number: (215) 928-3000, email: durga_borkar@meei.harvard.edu; Emily Eton, Kellogg Eye Institute, telephone number: (734) 763-8122, email: emily.eton@gmail.com; Nicole Koulisis, USC Roski Eye Institute, telephone number: (323) 442-6335, email: nkoulisi@gmail.com; Carolyn Kloek, Dean McGee Eye Institute, telephone number: (405) 271-1090, email: Carolyn-Kloek@dmei.org.

Contributor Information

The PCIOL Study Group members:

Sheila Borboli-Gerogiannis, Stacey Brauner, H. Peggy Chang, Kenneth Chang, Sherleen H. Chen, Matthew Gardiner, Scott H. Greenstein, Carolyn E. Kloek, Ann-Marie Lobo, and Z. Katie Luo

References

- 1. Wittenborn JS. The future of vision: Forecasting the prevalence and cost of vision problems. Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago, Prepared for Prevent Blindness, 2014. http://forecasting.preventblindness.org [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olson RJ, Braga-Mele R, Chen SH, et al. Cataract in the adult eye preferred practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2017;124:P1–119. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feder RS, Olsen TW, Prum BE, et al. Comprehensive adult medical eye evaluation preferred practice pattern guidelines. Ophthalmology 2016;123:P209–36. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Obeid A, Su D, Patel SN, et al. Outcomes of eyes lost to follow-up with proliferative diabetic retinopathy that received Panretinal photocoagulation versus intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmology 2019;126:407–13. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson AC, Thompson MO, Young DL, et al. Barriers to follow-up and strategies to improve adherence to appointments for care of chronic eye diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:4324–31. 10.1167/iovs.15-16444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, et al. Population-based assessment of the outcome of cataract surgery in an urban population in southern India. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;127:650–8. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00044-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bourne RRA, Dineen BP, Huq DMN, et al. Correction of refractive error in the adult population of Bangladesh: meeting the unmet need. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:410–7. 10.1167/iovs.03-0129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao J, Ellwein LB, Cui H, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of cataract surgery in rural China the China nine-province survey. Ophthalmology 2010;117:2120–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hashemi H, Mohammadi S-F, Z-Mehrjardi H, et al. The role of demographic characteristics in the outcomes of cataract surgery and gender roles in the uptake of postoperative eye care: a hospital-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2012;19:242–8. 10.3109/09286586.2012.691600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kheirkhah P, Feng Q, Travis LM, et al. Prevalence, predictors and economic consequences of no-shows. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:13. 10.1186/s12913-015-1243-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berg BP, Murr M, Chermak D, et al. Estimating the cost of no-shows and evaluating the effects of mitigation strategies. Med Decis Making 2013;33:976–85. 10.1177/0272989X13478194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lutski M, Shohat T, Mery N, et al. Incidence and risk factors for blindness in adults with diabetes: the Israeli national diabetes registry (INDR). Am J Ophthalmol 2019;200:57–64. 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu AM, Wu CM, Tseng VL, et al. Characteristics associated with receiving cataract surgery in the US Medicare and Veterans health administration populations. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:738–45. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang W, Yan W, Müller A, et al. Association of socioeconomics with prevalence of visual impairment and blindness. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:1295–302. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gupta S, Ravindran RD, Subburaman G-BB. Predictors of patient compliance with follow-up after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang G, Crooms R, Chen Q, et al. Compliance with follow-up after cataract surgery in rural China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2012;19:67–73. 10.3109/09286586.2011.628777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salter A, Chen A, Lee D, et al. Compliance with postoperative cataract surgery care in an urban teaching hospital. R I Med J 2014;97:48–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orr P, Barrón Y, Schein OD, et al. Eye care utilization by older Americans: the see project. Salisbury eye evaluation. Ophthalmology 1999;106:904–9. 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00508-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chou C-F, Barker LE, Crews JE, et al. Disparities in eye care utilization among the United States adults with visual impairment: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2006-2009. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154:S45–52. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McMullen MJ, Netland PA. Lead time for appointment and the no-show rate in an ophthalmology clinic. Clin Ophthalmol 2015;9:513–6. 10.2147/OPTH.S82151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy after Panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1386–92. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellis DA, McQueenie R, McConnachie A, et al. Demographic and practice factors predicting repeated non-attendance in primary care: a national retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e551–9. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30217-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cronin PR, DeCoste L, Kimball AB. A multivariate analysis of dermatology missed appointment predictors. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1435–7. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Google LLC . Google maps. Available: https://www.google.com/maps [Accessed 28 Apr 2018].

- 25. Internal Revenue Service . SOI tax stats - individual income tax statistics. Available: https://www.irs.gov/ [Accessed 15 Mar 2019].

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National health interview survey. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm [Accessed 30 Oct 2020].

- 27. National Instiututes of Health . Rethinking drinking. Available: https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/ [Accessed 30 Oct 2020].

- 28. Fudemberg SJ, Lee B, Waisbourd M, et al. Factors contributing to nonadherence to follow-up appointments in a resident glaucoma clinic versus primary eye care clinic. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:19–25. 10.2147/PPA.S89336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, et al. Loss to follow-up among patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration who received intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:1251–9. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Creps J, Lotfi V. A dynamic approach for outpatient scheduling. J Med Econ 2017;20:786–98. 10.1080/13696998.2017.1318755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shrestha MP, Hu C, Taleban S. Appointment wait time, primary care provider status, and patient demographics are associated with Nonattendance at outpatient gastroenterology clinic. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;51:433–8. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Singman EL, Smith K, Mehta R, et al. Cost and visit duration of same-day access at an academic ophthalmology department vs emergency department. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019;137:729. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Umfress AC, Brantley MA. Eye care disparities and health-related consequences in elderly patients with age-related eye disease. Semin Ophthalmol 2016;31:432–8. 10.3109/08820538.2016.1154171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elam AR, Lee PP. High-risk populations for vision loss and eye care underutilization: a review of the literature and ideas on moving forward. Surv Ophthalmol 2013;58:348–58. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paksin-Hall A, Dent ML, Dong F, et al. Factors contributing to diabetes patients not receiving annual dilated eye examinations. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2013;20:281–7. 10.3109/09286586.2013.789531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ellis DA, Jenkins R. Weekday affects attendance rate for medical appointments: large-scale data analysis and implications. PLoS One 2012;7:e51365. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hamilton W, Round A, Sharp D. Patient, hospital, and general practitioner characteristics associated with non-attendance: a cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:317–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Odonkor CA, Christiansen S, Chen Y, et al. Factors associated with missed appointments at an academic pain treatment center: a prospective year-long longitudinal study. Anesth Analg 2017;125:562–70. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller AJ, Chae E, Peterson E, et al. Predictors of repeated ‘no-showing’ to clinic appointments. Am J Otolaryngol 2015;36:411–4. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lagu T, Iezzoni LI, Lindenauer PK. The axes of access--improving care for patients with disabilities. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1847–51. 10.1056/NEJMsb1315940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cawthon PM, Marshall LM, Michael Y, et al. Frailty in older men: prevalence, progression, and relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1216–23. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. US Department of Health and Human Services . Profile of older Americans, 2018. Available: https://acl.gov/aging-and-disability-in-america/data-and-research/profile-older-americans/ [Accessed 30 Oct 2020].

- 43. Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, et al. Access to subspecialty care for patients with mobility impairment: a survey. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:441–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Javitt JC, Kendix M, Tielsch JM, et al. Geographic variation in utilization of cataract surgery. Med Care 1995;33:90–105. 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kilmer G, Bynum L, Balamurugan A. Access to and use of eye care services in rural Arkansas. J Rural Health 2010;26:30–5. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Control CfD, Prevention . The state of vision, aging, and public health in America. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walter C, Althouse R, Humble H, et al. West Virginia survey of visual health: low vision and barriers to access. Vis Impair Res 2004;6:53–71. 10.1080/13882350390487018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qiu M, Wang SY, Singh K, et al. Racial disparities in uncorrected and undercorrected refractive error in the United States. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:6996–7005. 10.1167/iovs.13-12662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154:S53–62. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Graves JA, Swartz K. Health care reform and the dynamics of insurance coverage-lessons from Massachusetts. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1181–4. 10.1056/NEJMp1207217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ndumele CD, Cohen MS, Cleary PD. Association of state access standards with accessibility to specialists for Medicaid managed care enrollees. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1445–51. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . State standards for access to care in medicaid managed care, 2014. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-11-00320.pdf [Accessed 30 Oct 2020].

- 53. Rathi S, Tsui E, Mehta N, et al. The current state of Teleophthalmology in the United States. Ophthalmology 2017;124:1729–34. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.