Abstract

Stroke has been called apoplexy since the ancient times of Babylonia. Johann Jakob Wepfer, a Swiss physician, first described the aetiology, clinical features, pathogenesis and postmortem features of an intracranial haemorrhage in 1655. Haemorrhagic and ischaemic strokes are the two subtypes of stroke. Bell’s palsy usually presents with an isolated facial nerve palsy. A lacunar infarct involving the lower pons is a rare cause of solitary infranuclear facial paralysis. The authors present the case of a 66-year-old woman presenting with a 3-day history of headache, vertigo, nausea, vomiting and facial weakness. Her comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. It was challenging to identify the pontine infarct on MRI due to its small size and the confounding presentation of complete hemi-facial paralysis mimicking Bell’s palsy. Our case provides a cautionary reminder that an isolated facial palsy should not always be attributed to Bell’s palsy, but can be a presentation of a rare dorsal pontine infarct as observed in our case. Anatomic knowledge is crucial for clinical localisation and correlation.

Keywords: emergency medicine, stroke

Background

Bell’s palsy usually manifests as an isolated facial nerve palsy, presenting with a sudden onset, usually over a period of hours and typically resolves over 6 months. Cerebral haemorrhage and infarction cause abrupt deficits of neurologic function. A cerebral haemorrhage may produce additional symptoms beyond neurological deficits such as vomiting, severe headache, rapid progression of neurological deficit and coma. Pontine infarcts cause 7% of all ischaemic strokes. Isolated pontine strokes contribute to 15% of all posterior circulation infarcts. The majority are lacunar infarcts involving basilar artery perforators. Hypertension, as in our case, is a major risk factor. Ischaemic stroke and Bell’s palsy are the most common causes of facial hemiparesis or hemiplegia. Isolated supranuclear facial palsy has been described as a lacunar syndrome of the supratentorial pyramidal tract.1

Case presentation

A 66-year-old woman, born in India, but resident of the UK for 40 years, presented to the emergency department with acute onset of left-sided facial weakness and numbness affecting her left leg and arm. She reported slightly slurred speech and altered visual acuity of her left eye. She described a 3-day history of temporal lobe headache, vertigo, nausea and vomiting. Her medical history included the diagnosis of triple-negative grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma of her left breast in 2019. She underwent wide local excision followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with docetaxel and radiotherapy 26 Gy in 5 fractions. She commenced treatment with adjuvant zoledronic acid 6 times per month for a total of 3 years.

She required surveillance with a mammogram annually for 5 years. She had type 2 diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. She sustained an ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 2000. Her medications included metformin 850 mg twice daly (bd), aspirin 75 mg once daily (od), omeprazole 20 mg od, amitriptyline 10 mg od, diltiazem 120 mg bd, ramipril 2.5 mg od, ferrous sulphate 200 mg bd, adcal D3 bd, tramadol 100 mg bd, atorvastatin 40 mg od, ibuprofen gel and solifenacin 10 mg od. She had no allergies. She was a non-smoker and did not consume alcohol. Her observations were as follows: SpO2 98% on air, Respiratory rate (RR) 16/min, Heart rate (HR) 108/min, Blood pressure (BP) 146/96 mm Hg and temperature of 36.7°C. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15/15. Physical examination revealed loss of her left-sided forehead creases, an inability to close her left eye, left facial muscle weakness, rightward deviation of the angle of the mouth on smiling and loss of the left nasolabial fold indicating a lower motor neuron pattern. There was no evidence of nuchal rigidity or rash. Left-sided sensory loss to light touch and pinprick affecting her face, arm and leg was also noted. There was no carotid bruit. Her visual fields were preserved and there was a full range of extraocular movements. Her pupils were equal and reactive to light. However, nystagmus was present. Cerebellar examination revealed no evidence of dysdiadochokinesia. Her gait and speech were normal and there was no evidence of ataxia. Normal power, tone and reflexes were present on examination of upper and lower limb neurology. Symmetrical deep tendon reflexes were present and both plantars were flexor. For patients with vertigo, as in our case, the HINTS (head impulse, nystagmus and test of skew) test is a diagnostic test that can help differentiate between a central and peripheral aetiology. Our patient presented with complete hemifacial paralysis, symptoms of persistent vertigo, nystagmus, nausea, vomiting and unilateral paraesthesia supporting a central aetiology rather than a peripheral cause.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations were unremarkable with normal clotting observed (table 1). Her blood gas showed normal physiology. A 12-lead ECG confirmed sinus tachycardia (rate: 108 beats/min). Her chest radiograph showed normal lung fields.

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations were unremarkable

| Haematology | Biochemistry | ||

| Haemoglobin | 118 g/L | Sodium | 138 mmol/L |

| White blood cell count | 7.0×109/L | Potassium | 4.3 mmol/L |

| Platelet count | 367 | Urea | 2.9 mmol/L |

| Mean cell volume | 89 fl | Creatinine | 59 umol/L |

| Haematocrit | 0.36 L/L | Albumin | 44 g/L |

| Basophil count | 0.02×109/L | Alkaline phosphatase | 113 IU/L |

| Neutrophil count | 4.3×109/L | Alanine transaminase | 13 IU/L |

| Monocyte count | 0.4×109/L | ||

| Eosinophil count | 0.07×109/L | Calcium | 2.31 mmol/L |

| Clotting | Calcium adjusted | 2.36 mmol/L | |

| APTT | 28.0 | C-reactive protein | 1 mg/L |

| Prothrombin time | 13.1 | Glucose | 6.5 mmol/L |

APTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time.

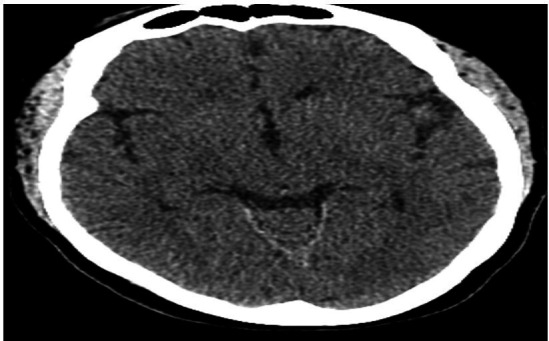

An unenhanced CT of the head was unremarkable (figure 1). Further investigation with an MRI of the head showed no evidence of a mass, haemorrhage, surface collection or a demarcated area of damage.

Figure 1.

An unenhanced CT of the head was unremarkable.

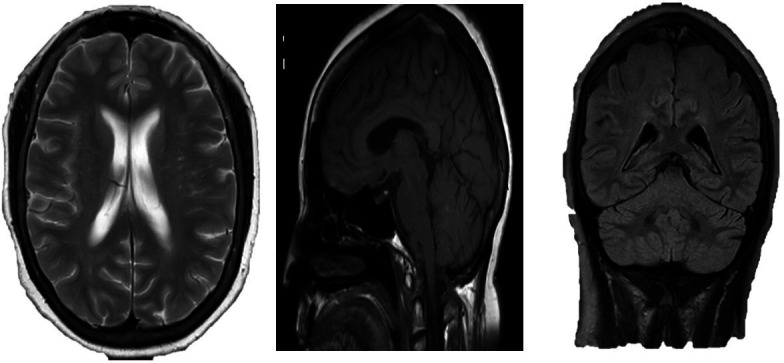

There was no focus of pathological enhancement. The skull vault and base were clear with no evidence of intracranial metastatic disease. Background microangiopathic change mainly affecting the pons was noted, which can occur from the sustained effects of elevated systemic blood pressure on the brain leading to lipohyalinosis (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Further investigation with an MRI showed no evidence of a mass, haemorrhage or metastasis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included a subarachnoid haemorrhage, Bell’s palsy, carcinomatosis or a stroke. A fluoroscopic-guided lumbar puncture showed no evidence to support the diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage. Her Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) protein was 0.43. Due to the acuity of her presentation, hypertension and background microangiopathic change on MRI, a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy appeared less likely. She was reviewed by the stroke consultant. The clinical examination findings were suggestive of a brainstem stroke, likely involving the facial nerve nucleus. Furthermore, her normal MRI of the head and cerebrospinal fluid made an oncological complication unlikely. Her MRI of the head was subsequently re-evaluated by a neuroradiologist and a tiny infarct was noted involving the left dorsal aspect of the pons. Therefore, a diagnosis of isolated facial nerve palsy due to a lacunar infarct of the dorsal pons was rendered.

Treatment

She commenced treatment with clopidogrel 75 mg once daily for 3 weeks and the plan was to continue with long-term aspirin 75 mg od. She was already prescribed adequate secondary prevention of stroke.

Outcome and follow-up

She was reviewed in the stroke clinic. A Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C), lipid profile and a 7-day ECG were requested to check for atrial fibrillation. Her MR angiogram showed no dissection within either the common or internal carotid artery. There was no evidence of vertebrobasilar disease, intracranial arterial stenosis, occlusion or aneurysm identified. Her blood pressure remained well controlled (101/66–129/89 mm Hg).

Discussion

Since the advent of ancient Greek and Roman times, stroke has been called apoplexy.

However, it was not until 1655 that Johann Jakob Wepfer, a Swiss physician, first described the clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and postmortem findings of an intracranial haemorrhage.2 Pontine infarcts contribute to 7% of all ischaemic strokes and 15% of all posterior circulation infarcts resulting in 1% of all new facial paralysis cases.3 Mostly, they are lacunar infarcts involving basilar artery perforators and other posterior circulation small vessels. Hypertension is a well-recognised risk factor. A lacunar infarct involving the lower pons is a rare cause of solitary infranuclear facial paralysis.4 The anterior inferior cerebellar artery, a branch from the basilar artery primarily supplies the facial nerve nucleus.

Infarcts within the facial nerve nucleus or its immediate outflow tract are responsible for central lesions that present with whole-sided facial weakness and are easily misdiagnosed as peripheral lesions.

Two major patterns of pontine infarcts resulting in a peripheral-type facial weakness have been recognised. Type A describes the lateral pontine lesion involving the pontine circumferential vessel of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory. Multivessel involvement can also be present. Emboli or branch atheromatous disease has been implicated in its aetiology.5 These lesions likely interrupt the distal facial nerve fascicles destined to exit in the cerebellopontine angle after looping around the ipsilateral abducens nucleus. Type B is characterised by a peripheral-type facial involvement and/or horizontal ocular disturbance. A focal mediodorsal pontine lesion adjacent to the fourth ventral ventricles is usually present. Small vessel occlusion has been implicated in its pathogenesis.

Rare pontine strokes that affect the ipsilateral facial nerve nucleus or facial nerve tract before it exits the pons have been shown to represent a central lesion that presents identically to a peripheral lesion. These insults occur acutely, whereas the onset of Bell’s palsy typically progresses over multiple hours to days and would not be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, dizziness or diplopia. Isolated facial nerve palsy usually manifests as Bell’s palsy and accounts for 72% of cases.6 It is a diagnosis of exclusion classically attributed to a herpes simplex mediated viral inflammation with demyelination and palsy. Unilateral Lower Motor Neuron Lesion (LMN) facial weakness develops over 24–48 hours, sometimes with an altered taste and hyperacusis. Pain behind the ear is common at onset. A vague altered facial sensation is often reported, although sensation is preserved on examination. Lyme disease may account for 25% of cases in endemic regions. HIV seroconversion is the most common cause in Sub-Saharan Africa. Early combination therapy with steroids improves outcome if started within 72 hours of symptom onset.

In an upper motor neuron lesion (UMNL), the pathology causing the muscle weakness lies centrally. In a lower motor neuron lesion (LMNL), the pathology is peripheral (between the spinal cord and the muscle). The signs that distinguish between an UMNL and an LMNL are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

How to distinguish an UMNL from an LMNL

| UMNL signs | LMNL signs |

| Increased tone Increased reflexes (Babinski reflexes) Clonus (sometimes) |

Decreased tone Decreased reflexes Fasciculations (sometimes) Wasting |

LMNL, lower motor neuron lesion; UMNL, upper motor neuron lesion.

The facial nerve (cranial nerve (CN) VII) is a mixed cranial nerve arising in the nucleus in the pons. It is a mixed cranial nerve with a predominant motor component, supplying all muscles concerned with unilateral facial expression. It carries sensory taste fibres from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue via the chorda tympani and supplies motor fibres to the stapedius muscle. It exits the skull through the stylomastoid foramen.7 Neurones in each nucleus supplying the upper face receives bilateral supranuclear innervation. An UMNL causes weakness of the lower part of the face on the opposite side with sparing of the frontalis muscle. An LMNL presents with complete unilateral weakness of all muscles of facial expression. The most common cause of an UMNL is a hemispheric stroke.

It is critical to have an understanding of anatomy to accurately delineate the site of the lesion. At the pons, CN VII loops around the abducens nerve nucleus leading to a lateral rectus palsy with unilateral LMN facial weakness. When the neighbouring paramedian pontine reticular formation and corticospinal tract are involved, there is a combination of:1 LMN facial weakness2 and failure of conjugate lateral gaze.3 A pontine tumour, for example, a glioma, multiple sclerosis and infarction can present with the aforementioned signs and symptoms. An acoustic neuroma, meningioma or metastasis can lead to compression of CN VII with the neighbouring CN V, CN VI and CN VIII. The facial nerve can be damaged along its anatomical pathway within its bony canal in the petrous temporal bone, within which lies the sensory geniculate ganglion. As well as LMN signs, lesions within this region can cause loss of taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and hyperacusis.

Causes include Bell’s palsy, trauma, a middle ear infection and herpes zoster (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). The facial nerve can also be compressed by skull base tumours and in Paget’s disease or sarcoidosis. Bilateral facial palsy is rare occurring in <1% of cases. Although a classic Foville syndrome is frequently mentioned in textbooks, a clear-cut case has yet to be observed in an alert patient with an ischaemic stroke.8

It is necessary to establish the risk factors for stroke. Our patient had a history of atherosclerotic risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia. Hemiparesis can occur as a post-ictal phenomenon or a result of migraine or hypoglycaemia. The post-ictal state may be associated with temporary (<24 hours) limb paresis (Todd’s paresis) in focal epilepsy, suggesting a structural lesion. Migraine with aura and systemic lupus erythematosus are also risk factors for stroke. Interestingly, a headache is unusual in a stroke or a transient ischaemic attack, although our patient presented with a 3-day history of an insidious headache. A sudden onset severe headache is suggestive of a subarachnoid haemorrhage. A unilateral headache preceding the limb weakness can occur in hemiplegic migraine. A gradual onset headache preceding the limb weakness is likely caused by an intracranial mass. Ocular signs with lower motor neuron facial weakness have been given several numerical eponyms after Miller-Fisher’s original description of one and a half syndrome.9 Haematological disorders such as thrombocythaemia, polycythaemia, hyperviscosity states and thrombophilia are weakly associated with arterial stroke but predispose to cerebral venous thrombosis. Anti-cardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant antibodies (anti-phospholipid syndrome] predispose to arterial thrombotic strokes in young individuals. Amyloidosis can present as recurrent cerebral haemorrhage. Neurosyphilis, mitochondrial disease and Fabry disease are also known risk factors.10 A pontine stroke can also result in ‘locked-in syndrome’.

Physical examination should include evaluation of the external ear for vesicles, which could indicate herpes zoster. In addition, the parotid gland should be palpated to identify masses that could affect the facial nerve pathway. Receptive dysphasia (the patient speaks fluently, often with jumbled words and phrases, but cannot comprehend language) suggests a lesion in Wernicke’s area. Individuals can also present with expressive dysphasia (comprehend language and follow instructions, but have word finding difficulties), suggesting a lesion affecting Broca’s area. The differential diagnosis includes idiopathic Bell’s palsy, HIV infection, Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster of the geniculate ganglion), Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, acoustic neuroma, parotid gland tumour, otitis media, Guillain-Barré syndrome and brainstem stroke. Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion, if one of the aforementioned causes is not identified. If the patient presents with a clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, serological testing following the two-tier testing of ELISA and immunofluorescence assay should be conducted.

Severe hypoglycaemia and hyperosmolar non-ketotic diabetic coma may also be misdiagnosed as a stroke. Millard-Gubler syndrome (ventral pontine syndrome) is a pontine lesion that produces ipsilateral VIth and VIIth nerve palsy with contralateral hemiparesis.

Ipsilateral facial paresis can also occur due to CN VII involvement.

Over the last several decades, clinicians have developed several different stroke scores to distinguish haemorrhagic from ischaemic infarction, but the most widely used is the Siriraj stroke score.11 General investigations in suspected stroke includes a full blood count (polycythaemia and anaemia), renal function tests, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and protein electrophoresis if hyperviscosity syndrome is suspected. A 12-lead ECG and a chest radiograph should be performed.

A thrombophilia screen is necessary if indicated by clinical or haematological features. If subacute bacterial endocarditis or a cerebral abscess is suspected, blood cultures should be performed. Physicians should not hastily abandon their clinical judgement when opposed by the initial CT of the head or MRI, yet they should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion.

Modifiable risk factors should be identified such as smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus. Statins reduce the risk of stroke in patients with a previous myocardial infarction. This case acts as a cautionary reminder of the importance of anatomical knowledge and of the inherent challenges when rendering the diagnosis of a pontine infarct.

Learning points.

A stroke denotes an acute neurological deficit. Strokes may vary in presentation, for example, a rapidly resolving neurological deficit to a severe permanent or progressive neurological defect such as multi-infarct disease. Risk factors for cerebrovascular disease should be sought, including a history of hypertension, the single most important risk factor for a pontine stroke, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia. It is important to establish a history of falls or trauma. Hemiparesis can occur as a post-ictal phenomenon, migraine or hypoglycaemia.

Establishing the exact time of onset is critical in suspected strokes because the window of time in which to establish the diagnosis and administer thrombolysis if appropriate is only 4.5 hours from the onset of symptoms. If the patient presents with visual and speech disturbance as well as limb weakness, it implies that pathology is likely to be central involving the brain rather than the spine or the peripheral nervous system.

The presence of diplopia, hemiparesis and a lower motor facial nerve lesion suggests a pontine stroke. A rapidly deteriorating level of consciousness, impaired extraocular movement and extensive sensorimotor deficits are clinical clues to establish the diagnosis. A decerebrate state is most likely due to a pontine lesion.

Footnotes

Contributors: LD: wrote the case report. RK: did the literature search. EF: edited the paper and gave final approval.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Huang CY, Broe G. Isolated facial palsy: a new lacunar syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984;47:84–6. 10.1136/jnnp.47.1.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wepfer JJ, Ott J. Observationes Anatomice ex cadaveribus eorum, quos sustulit apoplexia: cum exercitatione de ejus loco affect. Schaffhusii: Impensis Onophrii a Waldkirch, typis Alexandri Riedingii, 1675. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling L, Zhu L, Zeng J, et al. Pontine infarction with pure motor hemiparesis or hemiplegia: a prospective study. BMC Neurol 2009;9:25. 10.1186/1471-2377-9-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassetti C, Bogousslavsky J, Barth A, et al. Isolated infarcts of the pons. Neurology 1996;46:165–75. 10.1212/WNL.46.1.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrone L, Nannoni S, Del Bene A, et al. Branch atheromatous disease: a clinically meaningful, yet unproven concept. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;41:87–95. 10.1159/000442577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell's palsy. BMJ 2004;329:553–7. 10.1136/bmj.329.7465.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinnatamby CS. Last’s Anatomy Chapter 7. 501. Central Nervous System, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brogna C, Fiengo L, Türe U. Achille Louis Foville's atlas of brain anatomy and the Defoville syndrome. Neurosurgery 2012;70:1265–73. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31824008e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher CM. Some neuro-ophthalmological observations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1967;30:383–92. 10.1136/jnnp.30.5.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar and Clarks . Clinical medicine chapter 21. Ninth Edition. Neurological Disease, 2016: 829–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poungvarin N, Viriyavejakul A, Komontri C. Siriraj stroke score and validation study to distinguish supratentorial intracerebral haemorrhage from infarction. BMJ 1991;302:1565–7. 10.1136/bmj.302.6792.1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]