Abstract

We describe the use of rapid cycle tests of change to pretest and develop a Carers Assistive Technology Experience Questionnaire for a survey of informal carers of persons with dementia. The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is a commonly used improvement process in healthcare settings. We used this method for conducting rapid cycle tests of change through cognitive interviews to pretest the questionnaire. The items for the questionnaire were developed based on an earlier systematic review and qualitative study. PDSA cycles were used incrementally with learning from each cycle used to inform subsequent changes to the questionnaire prior to testing on the next participant.

Design

Qualitative with use of cognitive interviews through rapid cycle tests of change.

Setting

UK.

Results

Nine participants were recruited based on eligibility criteria and purposive sampling. Cognitive interviewing using think aloud and concurrent verbal probing was used to test the comprehension, recall, decision and response choice of participants to the questionnaire. Seven PDSA cycles involving the participants helped identify problems with the questionnaire items, instructions, layout and grouping of items. Participants used a laptop, smartphone and/or tablet computer for testing the electronic version of the questionnaire and one participant also tested the paper version. A cumulative process of presenting items in the questionnaire, anticipating problems with specific items and learning from the unanticipated responses from participants through rapid cycle tests of change allowed rich learning and reflection to progressively improve the questionnaire.

Conclusion

Using rapid cycle tests of change in the pretesting questionnaire phase of research provided a structure for conducting cognitive interviews. Learning and reflections from the rapid testing and revisions made to the questionnaire helped improve the process of reaching the final version of the questionnaire, that the authors were confident would measure what was intended, rapidly and with less respondent burden.

Keywords: qualitative research, geriatric medicine, quality in health care, dementia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study recruited participants from across the UK, adopting a purposeful sampling strategy to identify suitable participants with diverse age groups, gender, ethnicity and living arrangements, who could support interpreting and answering items within the questionnaire.

Use of concurrent think aloud and verbal probing methods during the cognitive interviews allowed for richer interpretation and in-depth understanding of changes needed to the questionnaire.

The participants were recruited through voluntary participation in research databases and potentially may not be representative.

Introduction

Dementia describes a set of symptoms that may include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem solving or language.1 Caring for a person with dementia can be demanding for carers (family, friends and neighbours) and can affect their mental and physical health and their social lives.2 Assistive technology (AT) may support carers in caring for persons with dementia in the community; however, very little is known about their experience and use of AT.3 4 To better understand the use and impact of AT on carers, we developed a survey instrument—Carers Assistive Technology Experience Questionnaire (CATEQ).

In survey research, the data collection tool is typically a structured questionnaire and the measurements obtained are the respondent’s answers to survey questions.5 This type of data collection assumes that all participants understand the questions in a consistent way; the questions are asking for information that participants have and can retrieve and the questions are worded in a way that the participants are able to answer them as intended by the researcher. In order to provide a valid and reliable instrument, the wording, structure and layout of the questionnaire must make allowance for the nature and characteristics of the participating population.6

Cognitive interviews

Cognitive interviews are commonly used for pretesting survey questions.5 7 They can provide information on how the questions are understood and answered by typical participants. Cognitive interviews can help detect problems participants may have in understanding survey instructions and items, and in formulating answers.8 Cognitive interviews can identify problems in item interpretation, memory retrieval, decision processes and response selection.9 A draft questionnaire with candidate items is developed and cognitive interviewing with participants representing the target population is used to revise the questionnaire. Cognitive interviews also afford the opportunity to detect other problems in questionnaire instructions, design and organisation.10 They consist of one-to-one interviews in which the respondents describe their thoughts while answering the survey questions and can be done through different methods such as think aloud, verbal probing, confidence rating, card sorting and paraphrasing.6 Cognitive interviews are usually undertaken in rounds, with several participants interviewed in each round, their responses analysed and changes to the questionnaire only made after each round.11–13 This process could be burdensome for respondents and researchers and involve higher costs during questionnaire development.

Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles

The iterative process of learning and revising through cognitive interviews can be viewed as following the steps of action-oriented learning such as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.14 15 PDSA cycles consist of14 16:

Plan: State the objective of the test, the planed change, make predictions of what will happen and why and develop a plan to test the change

Do: Carry out the test/intervention, document problems and unexpected observations, begin analysis of the data

Study: Complete the analysis of the data, compare the data to earlier predictions in the plan phase and summarise and reflect on what was learnt

Act: Determine what modifications should be made, that is, deciding that the intervention has achieved the required standard and can therefore be implemented more widely or deciding that an entirely new change is required and the current plan should be changed and prepare a plan for the next test

While PDSA cycles are commonly used in clinical care, few clinical research trials have documented its use for implementation17 and none have used PDSA cycles as a framework for cognitive interviews for pretesting questionnaires. The authors present here one way of developing a questionnaire, based on using rapid cycle tests for change framed within PDSA cycles for conducting cognitive interviews in pretesting questionnaire items to develop the CATEQ. This is an alternative way of developing and pretesting a questionnaire and highlights how rapid cycle tests for change such as PDSA cycles can be used in questionnaire development.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

This study is part of a larger research project which has a patient and public advisory group that meets twice a year. The group consists of two carers of persons with dementia and a person with dementia (all living in England). This group gave feedback on the initial items and instructions framed as part of the CATEQ and reviewed the final version of CATEQ submitted for ethical approval. This group has also committed to support dissemination of study results to other patient involvement groups and their wider networks.

Study design

The authors describe the steps followed in designing the questionnaire and conducting the cognitive interviews using PDSA cycles to arrive at the final version of the CATEQ.

Develop items for the questionnaire

The items of CATEQ were developed on the basis of results from a systematic review3 18 and a qualitative study4 and are intended to be administered as an electronic survey. The CATEQ explores themes that carers (family, friends and neighbours) described as relevant for use of AT for dementia care in the community. An iterative process of drafting, evaluation, revision and content checking was followed. Attention was taken to draft the items in the questionnaire to: capture the intended concept of experience using AT and their impact on carers; relevance to all members of the target population irrespective of age, living arrangements and relationship with the person with dementia; the response choices were ordered in a meaningful way; ensure the questions were worded in a manner consistent with best practice style guide by Alzheimer’s Society19; each item represented a single concept, rather than a multidimensional concept; the content of the items was appropriate for the recall period of the previous 4 weeks; and the items could be answered in a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire items were mainly closed questions with multiple-choice answers with some questions being partially closed with ‘other’ as open-ended text options. The questions were a mixture of behavioural (What input is required from you for using the assistive technology?; How often are you able to solve problems with the assistive technology by yourself?), opinion (How helpful is the assistive technology in reducing your stress?; How helpful is the assistive technology in giving you more time for yourself?) and factual questions (age; gender; who was involved in the choice of AT?). The CATEQ included questions to capture demographic information of participants, health-related quality of life and expression of interest in participating in qualitative interviews later. None of the questions except for the consent question at the beginning of the survey had a forced-choice response (ie, respondents could omit answers to questions). The draft questionnaire had a Likert-like rating scale as response choices. For ease of administering cognitive interviews the initial set of interviews did not include demographic (for participants 1–4) and health-related quality of life (participants 1–6) questions. This questionnaire was labelled draft 0 and minor corrections were made based on comments by the patient and public advisory group for the project and by three clinical and social care experts involved in prescribing AT for use by persons with dementia at home. This modified CATEQ was labelled draft 1 and was used in the first cognitive interview.

Design cognitive interview process

Cognitive interviews were used to assess participants’ comprehension of the items in CATEQ as well as establish that no important items were missing. A semistructured interview guide with think aloud questions, and verbal probing questions, was developed to elicit further information from the participants (box 1). All the cognitive interviews were conducted by VS who is an occupational therapist and is trained in qualitative interviewing and quality improvement methods. Regular time was made for all the authors to meet to discuss progress with the cognitive interviews and modifications to the drafts of CATEQ.

Box 1. Cognitive interview guide.

Preinterview

Participant to re-receive the information sheet and asked to read it through. Participant will be given a brief introduction to the research that includes a description of assistive technology.

Show university card for ID of researcher and introduce self.

Participant to be told what will happen during the interview process and reminded that the interview will also be audio recorded.

Participant to be told that a transcript will be made from the audio recording.

Participant to be told the method of analysis and reminded that they will remain anonymous, and that their data will be confidential.

Participant given time to ask questions.

Participant will be asked to sign two copies of the consent form, one of which is to be retained by the researcher.

Instructions

Based on our research, we have the following questions as part of the Carers Assistive Technology Experience Questionnaire. Please look at each page and the questions in this survey. During the interview, we will ask you to speak aloud about what you are thinking as you respond to questions. I am also going to ask you additional questions about individual items in this questionnaire. Remember, the purpose of this interview is to test the questionnaire and not to test you. Are you ready to begin?

We will start with the instructions for the survey.

Example verbal probes used to test the questions:

For Question abc…

1. What to you, is ‘………’?

2. Tell me more about ‘……’?

3. Can you repeat this question in your own words?

4. What does ‘…….’ mean to you?

5. Would you mind providing some examples about ‘….’?

6. When you think about ‘……’ what comes to your mind?

Overall for the survey…

7. Are there additional questions you believe should be asked?

8. Are there questions you believe should be deleted?

9. Are there questions you believe should be modified?

10. Are there words used in the questions that you think could be changed to make it more understandable to others who help/look after those with dementia?

Do you have any questions for me?

Recruitment

Participants for the cognitive interviews were recruited through the Join Dementia Research website.20 Participants were carers of persons with dementia based in the UK willing to be contacted by researchers through this website. The inclusion criteria were: adult carers—family, friends or neighbours—providing at least 10 hours of care (eg, shopping, leisure, personal care, finance) per week to a person with dementia who lives in their own home, with the carer living together with or away from the person with dementia; carers should have used at least one AT device at home in the previous year and be able to communicate in English. Participants were emailed a copy of the participant information sheet (online supplemental file 1) and a purposive sample of participants reflecting variations in gender, age, ethnicity, living arrangements and relationship with persons with dementia were selected. The recruitment commenced in October 2019 and the final interview was completed in February 2020. A target sample size of 7–10 participants was deemed enough to complete cognitive interviews for items in the CATEQ. This was based on previous estimates13 21 22 but the intention was to continue with cognitive interviews until no further amendments to the CATEQ were necessary.23

bmjopen-2020-042361supp001.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)

Conduct cognitive interviews

Data collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted face to face (at the participant’s own home/at the researcher’s office) taking into consideration the participant’s geographical location and preference. The ‘think aloud’ and verbal probing methods were used for data collection and involve an interviewer asking the participants how they went about answering a particular survey question.10 In the think aloud method, the participant is asked to speak all thoughts aloud as he/she answers the question. For verbal probing, the interviewer asks specific questions or probes which are designed to elicit how the participant went about answering the question, for example, how the participants made their choice among the response options or how they interpreted an instruction.5 6 Participants were shown the electronic version of CATEQ developed using Qualtrics software24 during the interview on a laptop. Participant 8 also tested the questionnaire on a smart mobile phone. The final participant in addition to the electronic version was also requested to comment on the paper version of CATEQ.21 The participants were not known to the interviewer or the other authors prior to recruitment. Trust and easing into the think aloud interview was built by establishing rapport with the participants. The interviewer (VS) explained that the purpose was to make the questionnaire better by identifying items that were difficult to answer. Interviews were undertaken using concurrent think aloud and verbal probing questions and lasted between 55 and 95 min; all interviews were audio recorded along with field notes and a PDSA template (online supplemental file 2). The field notes noted verbal and non-verbal cues from the participants, as well as their perception of the items in CATEQ. Confidentiality of the participants was maintained throughout the process by avoiding references to names of the participant or persons with dementia, cities and other person identifiable information.

bmjopen-2020-042361supp002.pdf (39.9KB, pdf)

Make decisions to revise questionnaire

Data analysis

The PDSA template (online supplemental file 2) was used to document the hypothesis being tested, results of the cognitive interview process, and to make changes to the CATEQ. After discussion among all the authors, the questionnaire items were changed in line with suggestions from the participant and accounting for difficulty encountered by the participant with specific items during the cognitive interview. Changes were made after every cognitive interview instead of waiting for rounds of interviews to finish, which is the process in traditional cognitive interview methods,13 thereby narrowing the time between data collection, analysis and changes made. The authors also ensured each subsequent participant, in addition to ‘thinking-aloud’ on a focused section of the questionnaire, also commented on the latest iteration of the full questionnaire to determine if the modified version then functioned as intended, without introducing further difficulties in comprehension or changes needed to the questionnaire. Subsequent CATEQ questionnaire drafts were numbered draft 2, draft 3, and so on, which were used contiguously for the progressive set of cognitive interviews.

Final test

At the end of questionnaire revision, the final version of CATEQ was tested on three volunteers and the patient and public advisory group to check for time taken to complete the questionnaire, issues with formatting, skip logic and ease of understanding of the instructions before it was deemed ready to be used in a quantitative survey.

Results

Emails (n=38) for recruitment were sent to potential participants. From the responses received (n=22), 11 carers did not meet the eligibility criteria and nine carers (five women and four men), with varying types of relationship to a person with dementia, took part in interviews (table 1). Every participant had used at least one AT device in the last 12 months. Participants were aged between 42 and 75 years. The authors used PDSA cycles for the cognitive interviews to make iterative changes to the CATEQ. The changes between draft 1 and draft 7 of the questionnaire are given in table 2.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| ID | Age range | Gender | Ethnicity |

| 1 | 56–70 | Female | White British |

| 2 | 56–70 | Male | White British |

| 3 | 40–55 | Female | White British |

| 4 | 40–55 | Male | Asian British |

| 5 | 71–85 | Male | White British |

| 6 | 56–70 | Female | Caribbean British |

| 7 | 40–55 | Male | White British |

| 8 | 40–55 | Female | Mixed White British |

| 9 | 40–55 | Female | Asian British |

Table 2.

Table of changes to CATEQ from draft version 1 to draft version 7

| Questionnaire structure | Draft 1 of CATEQ | Draft 7 of CATEQ | |

| 1 | Instructions | ||

| Line numbers | 16 | 41 | |

| Paragraphs | 12 | 12 | |

| 2 | Questions on assistive technology | 9 | 10 |

| Questions on previous assistive technology | 0 | 5 | |

| 3 | Matrix questions on experience and impact | 21 | 20 |

| 4 | Demographic questions | 0 | 9 |

| 5 | Health-related quality of life questions | 0 | 15 |

| 6 | End of survey response line number | 1 | 1+research website details |

| 7 | Layout and structure of questionnaire | ||

| Colour scheme | Blue progress bar | Green progress bar | |

| Font size | 12 | 15 | |

CATEQ, Carers Assistive Technology Experience Questionnaire.

PDSA 1: testing instructions and questionnaire items

CATEQ draft 1 had instructions for participating in the survey, eligibility criteria and a consent statement. In addition, it had 29 items (21 items in matrix format) about carers’ current experiences and impact of using AT with a person with dementia at home. During PDSA 1, participant 1 was able to comprehend and understand the instructions and commented on the font and layout of the instructions that could be improved. The eligibility criteria and consent statements were easy to understand, and overall participant 1 took less time than anticipated to complete these sections. On verbal probing, participant 1 indicated that most instructions only carried information regarding data protection and use which were standard statements.

…these are what…err…you’ll find in a product agreement you know…and who reads these through fully? I always click agree, so I can start using the thing, err…you know…like the cookie thing on websites…

Participant 1 answered the items on the questionnaire and commented that the layout was easy to follow, the questions were easy to understand with the option of ‘other’ where extra information was needed. As part of the think aloud interview for item 1, it was observed that there was some difficulty in sorting through AT devices that participant 1 had used but is no longer currently using, and additional instructions and questionnaire items to provide details of these devices might be helpful. At the end of the PDSA cycle, modifications to the layout and instructions were made by adjusting the font size and paragraph spacing, instructions for current AT were modified and four additional questions on previously used AT and reason for abandonment were added, as well as adding information on the research website at the end of survey message, and the CATEQ draft was labelled draft 2.

PDSA 2: testing questionnaire items

Cognitive interviews with participants 2 and 3 were carried out separately using the electronic version of draft 2 of CATEQ. Both participants felt the image at the start of the instructions with common AT devices was helpful. The think aloud interviews for the questionnaire items highlighted confusion regarding the cost of AT. The question was framed as: ‘Can you give the approximate cost (in pounds) associated with the assistive technology currently used, paid for by the person with dementia or by you or another carer (family, friend or neighbour)?’ Participant 2 had difficulty in separating out initial cost in purchasing the AT with that of ongoing costs for maintenance. Participant 3 also had difficulty with the cost of AT question ‘Are you concerned about cost of the assistive technology?’ as the AT they were using was provided by the social care services without a cost to them. Both participants were able to differentiate questions on anxiety and stress presented as separate questions. On verbal probing, both participants wanted a ‘does not apply’ option to matrix questions such as: ‘How helpful is the assistive technology in giving you additional time for tasks that you have to do?’ and ‘How helpful is the assistive technology in maintaining dignity of the person with dementia?’. These cognitive interviews also gave authors the unsolicited confirmation that the CATEQ could be self-administered.

…you’ll get more out of me doing this (answering the questions) on a laptop or on the phone than if I were sat in front of you and answering them…these are personal questions and (I) might be feeling guilty answering them honestly if you were in the room, you know what I mean… (Participant 2)

At the end of this PDSA cycle the questionnaire items were modified to change the wording on items on cost and add a ‘does not apply’ option to the Likert-type scale choice for the matrix questions and the new draft of the CATEQ was labelled draft 3.

PDSA 3: testing questionnaire items and skip logic

Cognitive interview with participant 4 was used to test the questionnaire items including the modified items from draft 2, as well as the layout and format of the electronic version of the questionnaire. The think aloud interview confirmed that the modified questionnaire items on cost were better understood by participant 4. On verbal probing, participant 4 appreciated the option of ‘does not apply’ as a choice. Participant 4 on verbal probing also commented that the layout of the questionnaire was easy to understand and suggested a change in colour scheme for the button indicating progress to the next page of the questionnaire:

…You know this arrow button in the bottom (indicates on screen), it is blue now, but if this were in green, other carers who do your survey would think they are good to go, sort of like…you know…like…like a traffic light system and make good headway with your questionnaire….

At the end of this PDSA cycle, the colour scheme for the questionnaire was changed and a new version of the CATEQ was labelled draft 4; this version for the next cognitive interview now contained items for capturing demographic data of participants.

PDSA 4: testing questionnaire items and demographic questions

Cognitive interview with participant 5 concentrated on questionnaire items with a specific focus on the nine demographic questions in CATEQ. Verbal probing and think aloud interview were used to check comprehension, recall and ease of answering demographic questions in the CATEQ. The participant understood the questions readily enough, participant 5 had some hesitation in answering the question on income and on verbal probing disclosed that the participant and the person with dementia pooled their income for household expenses and some of the hesitation was in disclosing this in a survey, even if it was anonymous. At the end of this PDSA cycle, it was decided to reframe the question on income to ‘family income’ and add an option of ‘do not wish to disclose’ as part of the response options of this question. After modifying the questionnaire items, further modifications to the instructions for survey participants were made on the advice of the ethics committee; this included further detailed instructions on use of data, data protection and contact details of all the study authors. The next version of CATEQ incorporating all these changes was labelled draft 5.

PDSA 5: testing modified instructions and questionnaire items

Participants 6 and 7 participated in cognitive interviews that tested the modified instructions and questionnaire items. Both participants completed the questionnaire items without difficulty and on verbal probing commented that the instructions were long but easy to understand and in any case were not spending too much time on them. On verbal probing, participant 7 also felt the order in which items on stress, anxiety, time for self and effort on caring were presented could be rearranged in the questionnaire and grouped together as they helped the participant think through them better and maintain ‘flow of thought’. Participant 6 also recommended testing the questionnaire on participants using a smartphone device, as this might be the way some participants would choose to complete the questionnaire during their commute into work. At the end of this PDSA cycle, questionnaire items were regrouped to facilitate ease of recall; items on health-related quality of life based on the validated 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12) version 125 26 plus three questions on coping with caring and relationship with person with dementia were added to the CATEQ, and this version of the questionnaire was labelled draft 6.

PDSA 6: testing items on health-related quality of life and completion of questionnaire using a smartphone

The next PDSA cycle involved a cognitive interview with participant 8, who tested additional items on the questionnaire from the SF-12. The SF-12 contains items covering physical functioning, social functioning, role functioning (physical and mental), vitality, bodily pain, mental health and general health. The SF-12 generates two summary scores: the physical component score and the mental component score. A higher score indicates better quality of life. As the SF-12 is well validated, the cognitive interview was limited to comprehension of the questions and answer choices as well as layout of the electronic version of the questionnaire with the health-related quality of life question items at the end of the questionnaire. The participant also completed the questionnaire using a smartphone device to check for ease of use and layout of the questionnaire in a smartphone device. The participant completed the questionnaire with ease and had no specific difficulty in comprehension or recall of information required for completion of the questionnaire. The layout of the questionnaire on the smartphone was easy to follow and the questions were presented one after the other and were completed without difficulty. At the end of this cycle, the questionnaire was deemed to be ready for a test to include electronic and paper versions to check ease of completion and minor modifications to instructions, such as to remove references to ‘IP address will not be collected’ and as skip logic could not be applied for consent to participate in future interviews. The next version of CATEQ was labelled draft 7.

PDSA 7: testing electronic and paper versions of the questionnaire

Participant 9 completed the CATEQ initially on a tablet computer and then as a paper version. Time taken to complete the questionnaire without prompts was 19 and 23 min, respectively. The additional time taken to complete the paper version was because participant 9 had to flip back and forth between the pages as the matrix questions asked about three AT devices that were currently used and the participants needed to remind themselves in which order they were answering this question.

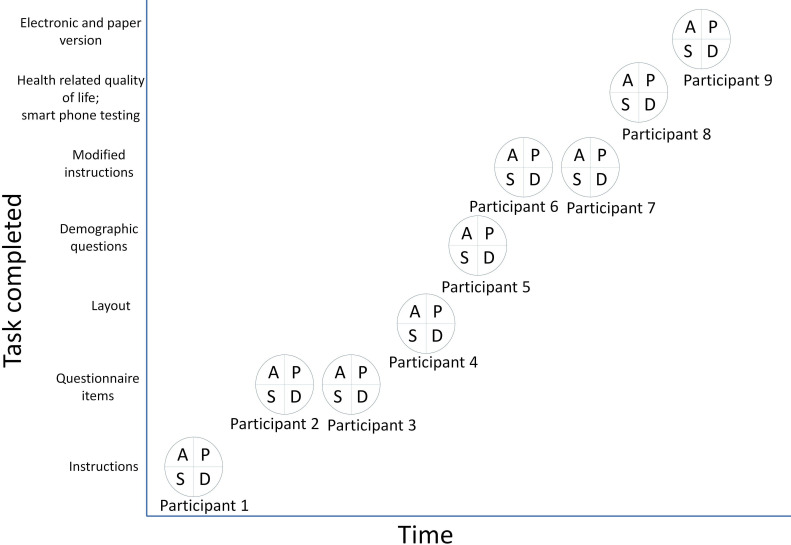

At the end of this PDSA cycle, the CATEQ was deemed to be ready to be used in a survey and was prepared for final comments by the patient and public advisory group. Figure 1 gives a visual depiction of the PDSAs and stages of tasks presented to subsequent participants.

Figure 1.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles and tasks involved in the cognitive interviews. Each cycle shows the focused section of the questionnaire that participants were asked to comment on.

Discussion

Cognitive interviews have helped researchers develop better questions and survey instruments and are increasingly being used routinely to pretest questionnaires.27 28 Our results showed rapid cycle tests of change using PDSA cycles as a format could be used as an alternate way of conducting cognitive interviews. Each cycle tested the changes made to the questionnaire and allowed quick and easy-to-test changes in subsequent versions of the questionnaire without increasing participant burden within the cognitive interview sessions. Cognitive interviews are usually undertaken in rounds, with several participants interviewed and changes to the questionnaire only made after each round.11 12 Problems in comprehension, recall or response choices to the questionnaire items emerge from the interviews themselves22 without the interviewer anticipating or having a hypothesis of which items or layout in the questionnaire may require change. Using small tests for change through PDSA cycles, on the other hand, enabled better structuring of questionnaire items with improved ease of comprehension, recall and response choices to items within this questionnaire. Using PDSA cycles as a learning mechanism for cognitive interviews resulted in predicting potential problems (what are we expecting to happen?) with questionnaire items and layout; this allowed the authors to focus on potentially problematic items such as, for example, questions on costs and freeing up carer time. Learning from each cognitive interview was used to inform the modifications that need to be carried out to the questionnaire and changes to the probing questions.27 29 Making changes to the questionnaire after every cognitive interview as a result became easier to manage, and learning from each cycle of the PDSA was applied to the next.30 31 Also, over the course of seven PDSA cycles, the think aloud interviews indicated potential problems with a questionnaire item or instruction other than the ones that were considered problematic; this unanticipated learning helped reframe and retest the questionnaire until it was satisfactory. Focusing on different items in the questionnaire and building up the testing helped reduce fatigue among the participants and better insight into item comprehension, language used and layout. Using PDSA cycles enabled rapid tests of change to questionnaire items, which provided information on problems in a question and its possible source(s), as well as information towards the problem’s solution.

Advantage of using rapid cycle tests for change

Unlike usual cognitive interviews, the use of rapid cycle tests of change in this questionnaire development allowed the authors to test on as small a scale as possible before building confidence and scaling up to test additional items in the questionnaire and with different devices and a paper version. The authors decided to divide questionnaire items for cognitive interviews during the planning phase into parts—instructions, questionnaire items, demographic data and health-related quality of life questions for pragmatic reasons. Planning to anticipate problems with questionnaire items this way and splitting the tasks into small manageable tests of change and increasing its complexity over the course of the PDSA cycles helped maximise learning opportunities, decrease costs and time taken to complete cognitive interviews and reduce participant fatigue and burden. The PDSA cycles allowed the ability to break things down and focus on making small, measurable changes.14 31 Testing using a paper version, a laptop and a smartphone helped identify if question wording communicates the objective of the question; and quickly identify problems such as redundancy, missing skip instructions and awkward wording with only a few interviews, instead of waiting for multiple participants in each round of interviews in the typical way cognitive interviews are conducted. PDSAs are a clever learning methodology whose ‘simplicity belies its sophistication’15; the use of iterative (PDSA) cycles for cognitive interviews provided information that would otherwise have been unseen by the interviewer before launch of the survey—for example, questions on AT devices that are no longer being used by carers. The PDSA cycles also helped our learning from unsolicited information such as the questionnaire could be self-administered instead of interviewer administered.

Cognitive interview is one component from a multitude of ways for pretesting a questionnaire, to assess it does collect the information that it is supposed to. Using rapid cycle tests for change through PDSA cycles included planning and a researcher hypothesis of the difficulty of the various questions in the questionnaire; this allowed rapid and iterative pretesting of the questionnaire without having to wait for multiple rounds of cognitive interviews before changes to the questionnaire could be made and retested again. The use of PDSA cycles to inform cognitive interviews in questionnaire development is another use for PDSAs and could be one way of pretesting questionnaires in the future.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The authors acknowledge that while cognitive interview methods can be used to evaluate existing questions, and to test proposed revisions to the original questions, they cannot provide quantitative evidence on whether the revised version of the question is better than the original; however, the action in each PDSA cycle built on the learning from the previous cycle and we are confident that the final version of the CATEQ is better than the first draft. The authors also acknowledge that some participants were less articulate than others and could not adequately verbalise their thought processes; however, a combination of think aloud and verbal probing interviews helped achieve the intended aim for each PDSA cycle of improving instructions and comprehension, recall and answering of items within the questionnaire.

Conclusion

The addition of cognitive interviews as an extra step in the survey development process assures data that are more likely to reflect the actual circumstances being examined. The use of PDSA cycles to frame the process of cognitive interviews would be an alternative way to pretesting questionnaires that minimises risks by using rapid small-scale tests of the changes introduced to layout and items in the questionnaire as well as potentially helping to reduce fatigue and burden to researchers and participants. The PDSA process is widely used and familiar to many involved in healthcare and appears to be an appropriate mechanism for pretesting questionnaires before deploying them in large-scale surveys in healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the three members of the patient and public engagement and involvement group set up as part of the carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia study for their comments on the questionnaire. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of all the participants in this study, for their time and invaluable insight into developing this questionnaire. The authors acknowledge the constructive comments from Dr Sushmitha Mohapatra and Wayne Scott and for their initial comments on the items in the questionnaire.

Footnotes

Twitter: @vimalsrir

Contributors: VS, CJ and MP conceived the design of the study. VS completed the cognitive interviews and PDSA cycles. VS, MP and CJ discussed emerging issues and agreed on the final changes to the questionnaire. VS drafted this version of the manuscript with critical revision and input from MP and CJ. All authors have read and given approval for this version. VS is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was granted ethical approval by the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee (reference number: R57703/RE001). All volunteers were provided with a participant information sheet. All recruited participants provided written informed consent prior to the cognitive interviews. All participants are identified only by a participant number within this paper.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author note: VS is a postgraduate student registered for his DPhil at the University of Oxford exploring informal carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia. VS is an Occupational Therapist and is trained in interviews and qualitative research methods as part of his clinical training and Masters in Evidence Based Healthcare course from the University of Oxford. VS is also a quality improvement expert and teaches and develops training packages including PDSA methodology for improving quality of care for patient benefit. MP is an Associate Professor within the Health Services Research Unit (HSRU), Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. CJ is Professor of Health Services Research and Director of the HSRU, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. MP and CJ have extensive experience in qualitative research methods and are joint supervisors of VS for the DPhil.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.WHO, World Health Organization . Dementia: A public health priority. Geneva: : World Health Organization, 2012. Available: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/ [Accessed 27 Nov 2017].

- 2.Brown A, Page TE, Daley S, et al. Measuring the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: development and validation of C-DEMQOL. Qual Life Res 2019;28:2299–310. 10.1007/s11136-019-02186-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sriram V, Jenkinson C, Peters M. Informal carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia care at home: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:160. 10.1186/s12877-019-1169-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sriram V, Jenkinson C, Peters M. Carers’ experience of using assistive technology for dementia care at home: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034460. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res 2003;12:229–38. 10.1023/A:1023254226592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brancato G, Macchia S, Murgia M. Handbook of recommended practices for questionnaire development and testing in the European statistical system. Rome, 2006. Available: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/EconStatKB/KnowledgebaseArticle10364.aspx [Accessed 27 Mar 2020].

- 7.Campanelli P, Blake M, Mackie M. Mixed modes and measurement error: using cognitive interviewing to explore the results of a mixed modes experiment. London, 2015. Available: https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/research/publications/working-papers/iser/2015-18.pdf [Accessed 7 Oct 2019].

- 8.Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo A, et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:224–34. 10.1002/nur.20195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nápoles-Springer AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H, et al. Using cognitive interviews to develop surveys in diverse populations. Med Care 2006;44:S21–30. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245425.65905.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García AA. Cognitive interviews to test and refine questionnaires. Public Health Nurs 2011;28:no. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen MM, Kjær-Sørensen P, Midtgaard J, et al. A Danish version of the life-space assessment (LSA-DK) - translation, content validity and cultural adaptation using cognitive interviewing in older mobility limited adults. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:312. 10.1186/s12877-019-1347-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy M, Hollinghurst S, Salisbury C. Qualitative assessment of the primary care outcomes questionnaire: a cognitive interview study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:79. 10.1186/s12913-018-2867-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis GB, Artino AR. What do our respondents think we're asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:353–6. 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:290–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed JE, Card AJ. The problem with plan-do-study-act cycles. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:147–52. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 2nd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coury J, Schneider JL, Rivelli JS, et al. Applying the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach to a large pragmatic study involving safety net clinics. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:411–21. 10.1186/s12913-017-2364-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sriram V, Jenkinson C, Peters M. Informal carers’ experience and outcomes of assistive technology use in dementia care in the community: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2019;8:158. 10.1186/s13643-019-1081-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzhemier’s Society . Positive language- An Alzheimer’s Society guide to talking about dementia. London, 2018. Available: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Positivelanguageguide_0.pdf [Accessed 12 Apr 2019].

- 20.National Institute of Health Research, Alzhemier’s Society . Join dementia research, 2019. Available: https://www.joindementiaresearch.nihr.ac.uk/home?login [Accessed 2 Jul 2019].

- 21.Coons SJ, Gwaltney CJ, Hays RD, et al. Recommendations on evidence needed to support measurement equivalence between electronic and paper-based patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: ISPOR ePRO good research practices Task force report. Value Health 2009;12:419–29. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klingshirn H, Mittrach R, Braitmayer K, et al. RECAPDOC - a questionnaire for the documentation of rehabilitation care utilization in individuals with disorders of consciousness in long-term care in Germany: development and pretesting. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:329. 10.1186/s12913-018-3153-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing planning and conducting cognitive interviews. In: Cognitive interviewing, 2014: 136–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qualtrics UK . Qualtrics - Res Surv Exp Softw, 2020. Available: https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/ [Accessed 16 Apr 2020].

- 25.Jenkinson C, Layte R. Development and testing of the UK SF-12. J Health Serv Res Policy 1997;2:14–18. 10.1177/135581969700200105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.RAND Healthcare . 12-Item short form survey (SF-12)., 2020. Available: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/12-item-short-form.html [Accessed 1 May 2020].

- 27.Drennan J. Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs 2003;42:57–63. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridolfo H, Schoua-Glusberg A. Analyzing cognitive interview data using the constant comparative method of analysis to understand cross-cultural patterns in survey data. Field methods 2011;23:420–38. 10.1177/1525822X11414835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2--assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011;14:978–88. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berwick DM. Developing and testing changes in delivery of care. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:651. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNicholas C, Lennox L, Woodcock T, et al. Evolving quality improvement support strategies to improve Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle fidelity: a retrospective mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:356–65. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-042361supp001.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-042361supp002.pdf (39.9KB, pdf)