Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a genetic disorder affecting the skin, nervous system, eyes and bones. Pulmonary involvement is unknown to many physicians. Yet, patients may be affected by lung bullae and cysts, which represent an increased risk for secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP). We present a 56-year-old patient with a pathogenic variant of the NF1 gene, who suffered from NF1 with lung manifestations and recurrent SSP. It is essential to identify the patients having an increased risk of developing SSP as preventive surgery seem to decrease the risk of new events. Pneumothorax can be a clinical manifestation of NF1 but is not yet widely acknowledged as such.

Keywords: dermatology, genetics, pneumothorax, respiratory medicine

Background

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a condition which affects the skin, eyes, lungs, bones and nervous system. NF is classified in three heterogeneous groups: NF1, NF2 and schwannomatosis. NF1, also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease, is the most common form with a prevalence of approximately 1 per 3000.1 NF1 is an autosomal dominant disease caused by a mutation of the NF1 gene. The mutation is, however, not a diagnostic criterion. The diagnosis is based on the presence of two or more of the clinical features presented in box 1.2

Box 1. Clinical features of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Six or more café-au-lait macules

Two or more neurofibromas, or one or more plexiform neurofibroma

Skinfold freckling of axilla or groin

Optic pathway glioma

Two or more Lisch nodules

Characteristic bony dysplasia (sphenoid wing dysplasia, thinning of the long bone cortex)

First-degree relative with NF1

Thoracic manifestations are most commonly cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas on the chest wall and kyphoscoliosis.3 Skeletal manifestations include deformities of the ribs, posterior vertebral scalloping and enlargement of the intervertebral foramen. Many physicians are not aware that up to 10%–20% of the patients have involvement of the lungs.4 The pulmonary manifestations include apical lung bullae and cysts, thin-walled bullae, interstitial parenchymal lesions and NF-related interstitial lung disease with bilateral, symmetrical and basal involvement of the lungs. Intrathoracic neurogenic tumours, meningoceles and plexiform neurofibromas of ribs, chest wall, lungs and mediastinum have also been described.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man diagnosed with NF1 was referred to our clinic with a suspicion of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD) due to a history of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. He was diagnosed with NF1 28 years earlier. The physical examination of the patient showed multiple café-au-lait macules, freckling of axillae and groins, multiple neurofibromas and plexiform neurofibromas on his face, trunk and extremities, and fibromas of the tongue. The patient was also known to have an optic pathway glioma in his right eye. He had a mother and a sister with known NF1. He thereby met five of the diagnostic criteria of NF1 including first-degree relatives with NF1.

He was a former smoker with a smoking history of 10 pack years. During the years, he had seven neurofibromas and one malignant schwannoma removed. Furthermore, he had a variety of other health issues including Barrett’s oesophagus, irritable bowel syndrome, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and conductive hearing loss on his right ear.

He had a remarkable history of at least four incidents of pneumothorax. Both lungs had been involved, and each pneumothorax was treated by tube thoracostomy. The most recent incident was in 2006. The patient attended his general practitioner as he experienced shortness of breath and pain located to the left side of the chest. An X-ray showed an apical pneumothorax of the left lung. The pneumothorax was treated by tube thoracostomy for two days, until the lung was fully inflated. He was referred to the Department of Thoracic Surgery as several bilateral lung bullae and apical cysts were demonstrated on a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (figure 1). However, the cysts were not removed surgically due to the diffuse localisation. Furthermore, it had been 10 years since the previous incidence of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP). It was argued in the medical record that the operation would not benefit the patient, and the risk of doing harm was too great. The same reason was given, when a chest scan in 2017 revealed several cysts, bilateral paraseptal and centrilobular emphysema, pleural thickening, and fibrosis causing interstitial lung disease.

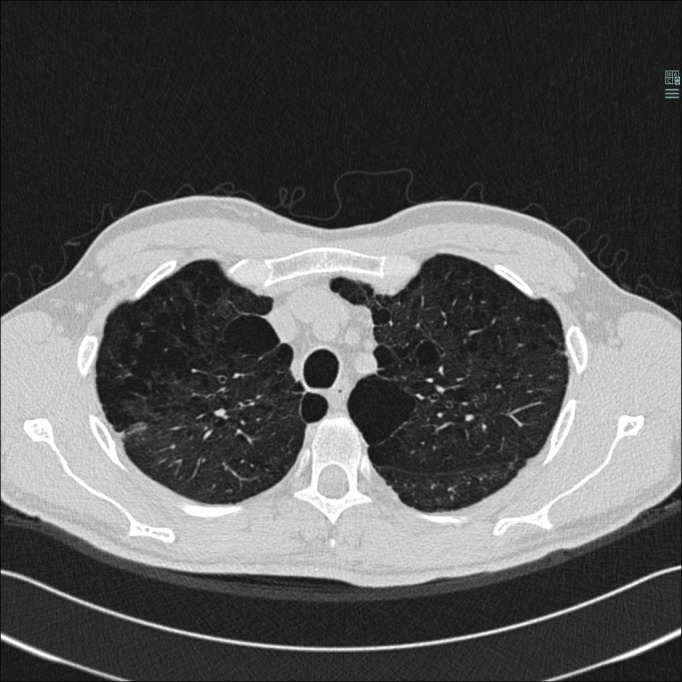

Figure 1.

HRCT from 2007. The scan is showing apical lung cysts and paraseptal, bullous and centrilobular emphysema. Areas without emphysema or lung cysts are affected by ground glass opacities.

The patient was genetically tested for NF1 and BHD, and was found to have a pathogenic variant only in the gene encoding NF1 (c.6709C>T; p.Arg2237).

Outcome and follow-up

The Centre of Rare Diseases is following the course of the patient’s disease by regular follow-ups. The patient has not had any worsening in his pulmonary aspects, although he does suffer from shortness of breath.

The patient is still seen at the Department of Dermatology for follow-up. The treatment consists of CO2 laser to reduce the neurofibromas and surgery to remove deeper neurofibromas causing him pain and discomfort.

Discussion

In this case, BHD was considered by the clinical geneticist due to the recurrent episodes of SSP. In about 5%–10% of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax, the underlying disorder is BHD, which is characterised by lung cysts, renal tumours and fibrofolliculomas.5 BHD is caused by a mutation of the FLCN gene of which our patient was tested negative. Other genodermatoses with pulmonary involvement and possible pneumothorax include tuberous sclerosis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Langerhans cell histiocytosis and NF1 of which our patient was affected.6 7 Neither the pulmonologists nor the thoracic surgeons associated the pneumothorax with the patient’s NF1.

Differential diagnoses of NF1 include NF2, Legius syndrome, familial café-au-lait macules, Noonan syndrome and constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency syndrome.1 8 NF1 is genetically and clinically distinct from the above mentioned, but especially the neurofibromas can be mistaken for other types of tumours. Genetic testing can therefore help to differentiate NF1 from other diseases. The diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by a disease-causing mutation of the NF1 gene. Due to his two first-degree relatives with NF1, the mutation seems likely to be inherited, although none of the family members have been genetically tested. The patient also had a son, who had spontaneous pneumothorax at the age of 17, but lacked other clinical features of NF1.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case with a pathogenic variant of the NF1 gene and SSP. In the literature, we found one case reporting spontaneous pneumothorax as the initial presentation of NF1.9 To investigate the association between NF1 and pneumothorax, a PubMed search was carried out. This revealed 10 published cases of pneumothorax in NF1 (table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of pneumothorax in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)

| Ayed et al19 | Engdahl et al9 | Gangadi et al20 | Nardecchia et al21 | Nguyen et al10 | Satar et al17 | |

| Clinical features | Café-au-lait macules and spontaneous pneumothorax | Café-au-lait macules, soft tissue masses, and spontaneous pneumothorax | Neurofibromas and spontaneous pneumothorax | Café-au-lait macules and spontaneous pneumothorax | Café-au-lait macules, inguinal freckling, neurofibromas, pheochromo-cytoma, and spontaneous pneumothorax | Axillary freckling, café-au-lait macules, bilateral Lisch nodules, neurofibromas, first-degree relative with NF1, mixed-type hearing loss, and spontaneous pneumothorax |

| Radiology | Apical, paraseptal and parenchymal lung bullae, paraseptal emphysema, apical pleural thickness, and subpleural nodules | Spinal and paraspinal tumours | Centrilobular emphysema, subpleural thin-walled lung cysts, bilateral basal reticular opacities, basal linear atelectasis, and subcutaneous nodules on the chest wall | Bilateral apical lung bullae and emphysema | Asymmetric pulmonary oedema, paraseptal and centrilobular emphysema, ground glass opacities, and pneumatoceles | Air cysts in upper lobes |

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | N/A | Smoker (50 pack years) | Non-smoker | Smoker (33 pack years) | Smoker |

The PubMed search for NF1 and pneumothorax gave four additional hits. These were not included due to other languages than English, German or French.

N/A, not applicable.

All but one of the published cases had pulmonary manifestations of NF1, besides pneumothorax, and two of the cases were known non-smokers. Smoking might increase the risk of interstitial lung disease,4 10–12 but the incidence of SSP is independent of smoking habits.12 13 The literature seems to agree that cystic, bullous or emphysematous lung disease are distinct clinical manifestations of NF1. None of the cases reported NF-associated interstitial lung disease characterised by pulmonary fibrosis or symmetrical, basal affection of the lungs. Thus, the occurrence of SSP is likely a clinical feature directly associated with the cystic and bullous lung manifestations of NF1 itself, and not a result of the NF-associated interstitial lung disease. Thereby, pneumothorax may be directly caused by NF1.

Correlation between genotype and phenotype in NF1 is not yet well known due to gene size, phenotypic complexity, heterogeneity of genotype and phenotype, and phenotypic progression with age. In the literature, only few correlations have been identified.14 15 The pathogenic variant of the NF1 gene of our patient is well described among patients with NF1.16 It is worth noticing that Satar et al reported a case of first-degree family history of NF1 and clinical features similar to our patient.17 Both had skinfold freckling, café-au-lait macules, multiple neurofibromas and mixed-type hearing loss as well as recurrent pneumothorax. This is the only other case besides ours to report recurrent pneumothorax and first-degree relatives with NF1. As none of the reported cases in table 1 were genetically tested, it is uncertain whether the pneumothorax of the patients was linked to genotype. Thus, a possible genotype–phenotype correlation between SSP and NF1 cannot be directly addressed.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is painful for the patients and can be lethal in 4.6% of the cases.13 It is therefore important that the clinician is attentive to the pulmonary manifestations of NF1 characterised by lung cysts and bullae. It is essential to identify the patients having an increased risk of developing SSP as preventive surgery seem to decrease the risk of new events.13 18

Our case represented a male who met five of the diagnostic criteria of NF1 with pulmonary manifestations including several lung cysts and bullae and at least four incidents of SSP. This should lead to consideration of NF1 as the aetiology of pneumothorax incidents. The diagnosis of NF1 was confirmed by genetic testing showing a pathogenic variant of the NF1 gene. To address a genotype–phenotype correlation between disease causing variants of the NF1 gene and pneumothorax, genetic testing and screening for pulmonary manifestations in patients with NF1 are recommended for future clinical studies. Clinicians need to be aware, that pneumothorax can be a manifestation of NF1.

Learning points.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is a clinical presentation of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) caused by lung cysts and bullae.

NF1 should be considered in patients presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax.

It is of great importance that the clinicians are attentive about pulmonary manifestations in patients diagnosed with NF1.

Early diagnosis of pulmonary manifestations in patients with NF1 is crucial as surgical removal of lung cysts and bullae seem to prevent spontaneous pneumothorax.

An examination of genotype–phenotype correlation between NF1 and pneumothorax could be of interest to identify patients at risk.

Footnotes

Contributors: TL wrote the first draft and edited the final version of the manuscript. AB commented, cowrote and edited the final version of the manuscript. HM edited the pulmonary aspects and critically revised the manuscript. MJZL-T provided the patient’s chest scans and revised the manuscript. AB was involved in the care of the patient.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gutmann DH, Ferner RE, Listernick RH, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17004. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . ICD‐11 for mortality and morbidity statistics (ICD‐11 MMS) 2020 version. Available: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l‐m/en

- 3.Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med 1981;305:1617–27. 10.1056/NEJM198112313052704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alves Júnior SF, Zanetti G, Alves de Melo AS, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: state-of-the-art review with emphasis on pulmonary involvement. Respir Med 2019;149:9–15. 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johannesma PC, Reinhard R, Kon Y, et al. Prevalence of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome in patients with apparently primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur Respir J 2015;45:1191–4. 10.1183/09031936.00196914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, et al. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:1044–53. 10.1164/rccm.200610-1483OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alper J, Kegel M. Skin signs in pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med 1987;8:299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues LOC, Batista PB, Goloni-Bertollo EM, et al. Neurofibromatoses: part 1 - diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014;72:241–50. 10.1590/0004-282X20130241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engdahl R, Vivas D, Lajam F. Spontaneous pneumothorax as initial presentation of neurofibromatosis. Am Surg 2010;76:1034. 10.1177/000313481007600951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen KA, Elnaggar M, Gallant NM, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a case highlighting pulmonary and other rare clinical manifestations. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018. 10.1136/bcr-2017-222614. [Epub ahead of print: 31 Jan 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamora AC, Collard HR, Wolters PJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis-Associated lung disease: a case series and literature review. Eur Respir J 2007;29:210–4. 10.1183/09031936.06.00044006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehal N, Arce Gastelum A, Millner PG. Neurofibromatosis-Associated diffuse lung disease: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus 2020;12:e8916. 10.7759/cureus.8916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onuki T, Ueda S, Yamaoka M, et al. Primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: prevalence, clinical features, and in-hospital mortality. Can Respir J 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/6014967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang E, Kim Y-M, Seo GH, et al. Phenotype categorization of neurofibromatosis type I and correlation to NF1 mutation types. J Hum Genet 2020;65:79–89. 10.1038/s10038-019-0695-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasmant E, Vidaud M, Vidaud D, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1: from genotype to phenotype. J Med Genet 2012;49:483–9. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahsold R, Hoffmeyer S, Mischung C, et al. Minor lesion mutational spectrum of the entire NF1 gene does not explain its high mutability but points to a functional domain upstream of the GAP-related domain. Am J Hum Genet 2000;66:790–818. 10.1086/302809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satar S, Ozcan A, Kara T, et al. Neurofibromatosis with recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. Chest 2015;148:433A. 10.1378/chest.2235522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichinose J, Nagayama K, Hino H, et al. Results of surgical treatment for secondary spontaneous pneumothorax according to underlying diseases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:1132–6. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayed Della S, Kotti A, Ben Sik Ali H, et al. [Spontaneous pneumothorax and Recklinghausen's disease: a case report]. Rev Pneumol Clin 2012;68:202–4. 10.1016/j.pneumo.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gangadi M, Panagoulias V, Manti A, et al. AB035. neurofibromatosis as a cause of cystic lung disease. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:AB035. 10.21037/atm.2016.AB035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nardecchia E, Perfetti L, Castiglioni M, et al. Bullous lung disease and neurofibromatosis type-1. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012;77:105–7. 10.4081/monaldi.2012.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]