Abstract

Parkes Weber syndrome is a fast-flow and slow-flow vascular anomaly with limb overgrowth that can lead to congestive heart failure and limb ischemia. Current management strategies have focused on symptom management with focal embolization. A pediatric case with early onset heart failure is reported. We discuss the use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling to guide a surgical management strategy in a toddler with an MAP2K1 mutation.

Keywords: Parkes Weber syndrome, Computational fluid dynamics modeling, MAP2K1 mutation, Congestive heart failure, Arterial banding

1. Case presentation

The patient was born full term and was seen in Seattle Children’s Vascular Anomalies Clinic at four days of age due to concern for a large capillary malformation with overgrowth involving the left upper extremity, chest and shoulder (Image 1). He was otherwise doing clinically well with normal somatic growth. A conservative management approach was pursued, and Genetics consultation was obtained. At his follow-up evaluation at 2 months of age his weight had fallen from the 75th percentile to 25th percentile. His parents reported equal use of both upper extremities, but he had had a single 24-h episode of left upper extremity pain with flexion. He had tachypnea and retractions on exam, which his parents confirmed to be his baseline respiratory status. His left upper extremity was markedly enlarged compared to his right and was warm to touch. Due to his tachypnea, a chest radiograph was obtained (Image 2) which showed cardiomegaly and pulmonary vascular congestion. He was admitted and medically managed with diuretics and fortified feeds. There was no family history of individuals with vascular malformations, nosebleeds, or early onset stroke. His head circumference was normal. His symptoms improved and he was discharged home with continued close follow-up.

Image 1. Neonatal Lesion:

Vascular anomaly identified at 4 days of age.

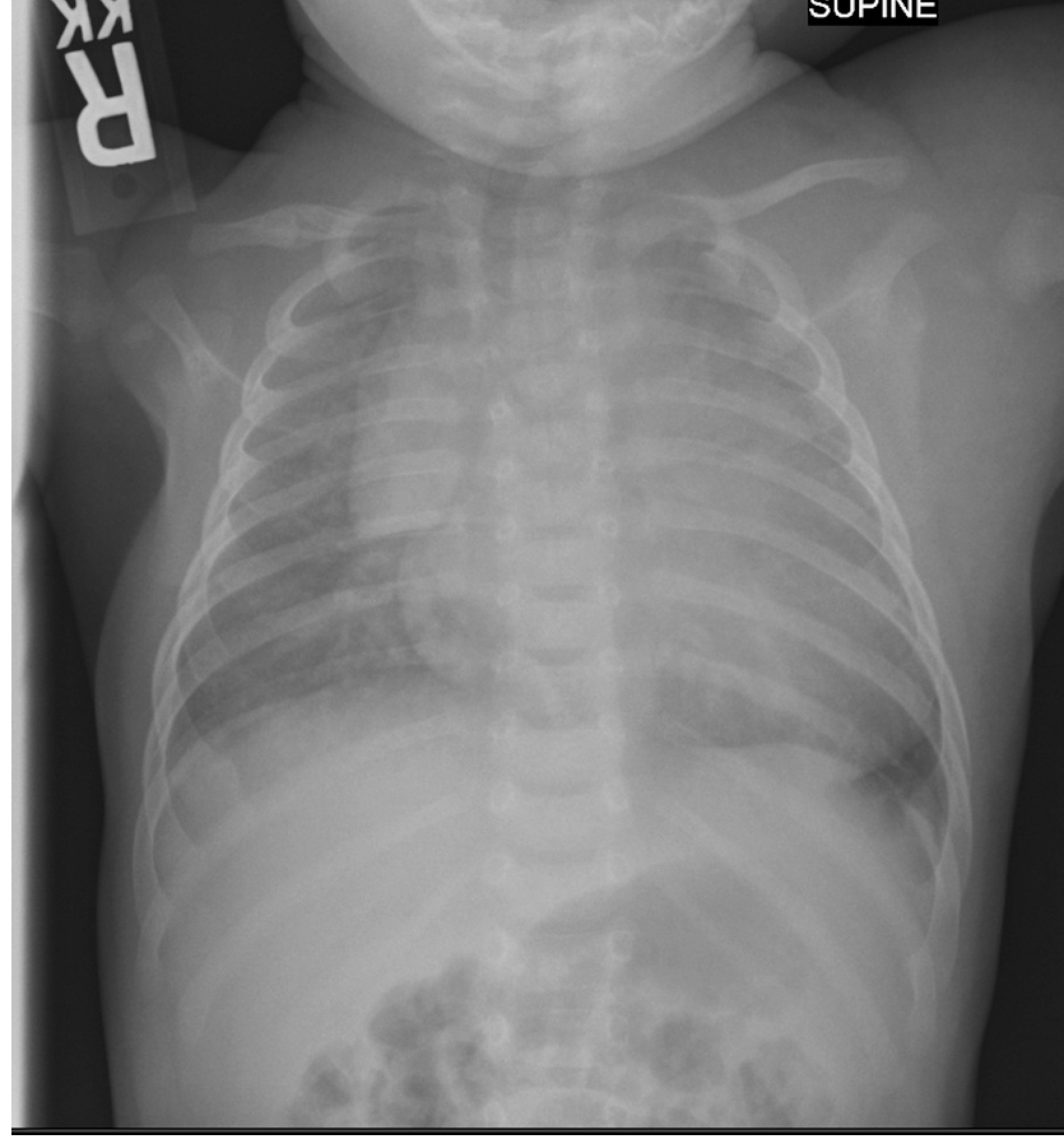

Image 2. Chest Radiograph:

obtained at 2 months of age demonstrating cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema, consistent with over-circulation and resultant congestive heart failure.

2. Imaging

An echocardiogram was performed that showed prominent left upper extremity arterial and venous flow with a dilated left subclavian artery, innominate vein and superior vena cava as well as a mildly dilated left atrium and moderately dilated left ventricle with normal systolic function.

Contrast-enhanced MR angiogram of the left upper extremity demonstrated enlarged, tortuous arteries and veins throughout the entire left upper extremity extending from the origin of the subclavian artery to the brachial artery (Image 3). The left subclavian artery exceeded the size of the descending aorta. There was early venous drainage into dilated draining veins consistent with shunting. There were multiple collaterals and venous tangles visualized throughout the entire upper extremity. There was a focus of increased short inversion time inversion recovery (STIR) signal abnormality in region of the left subscapularis muscle, thought to be a component of the vascular malformation.

Image 3. Magnetic Resonance Angiogram:

Demonstrates extensive left upper extremity vascular anomaly. Notice that the left subclavian artery (red arrow) is larger than the aorta (yellow arrow).

A limited non-contrast brain MRI was normal without evidence of polymicrogyria, Chiari malformation, or other vascular malformation.

3. Fluid dynamics modeling

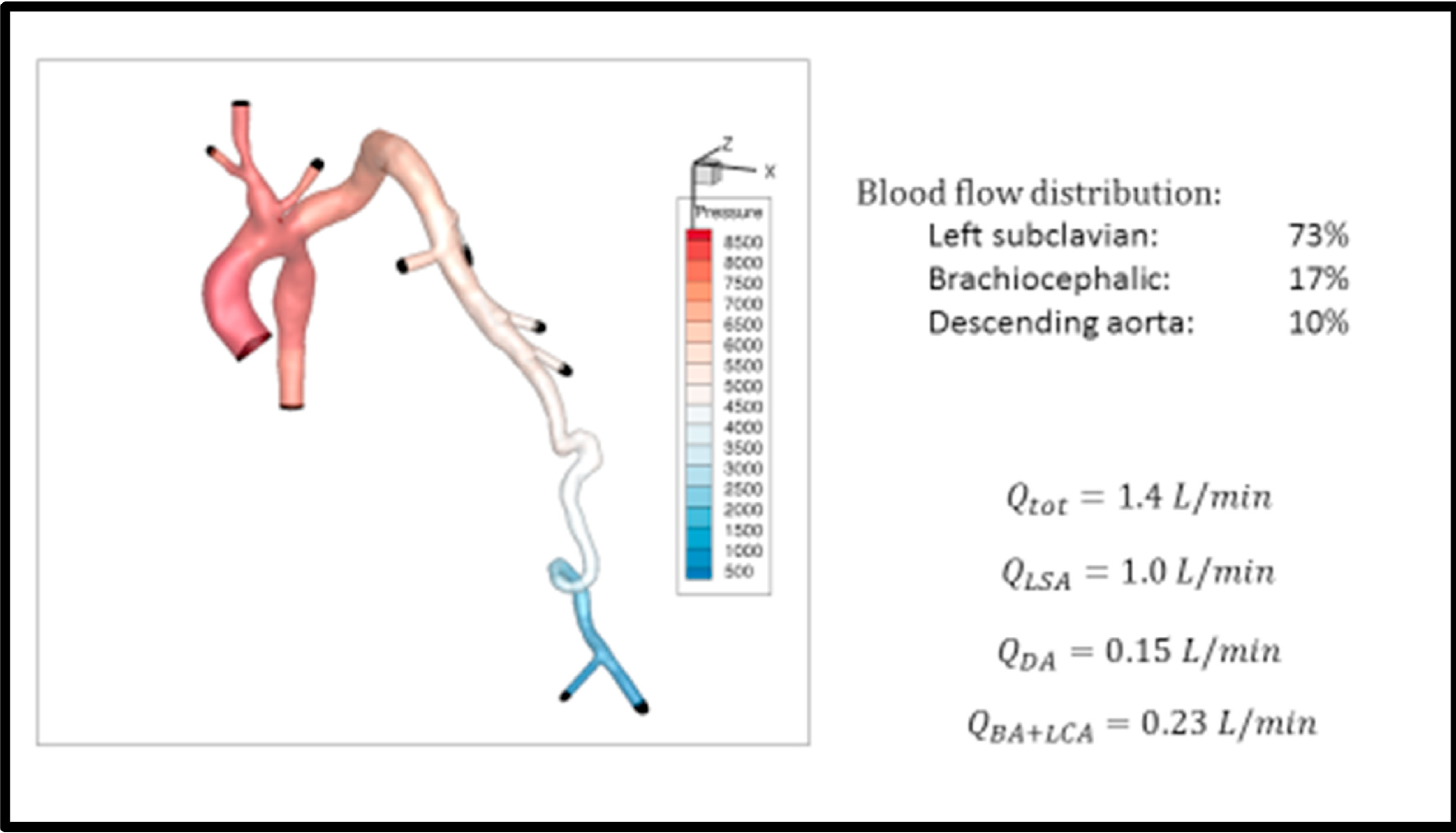

Flow analysis was performed by the engineering team at the University of Washington Cardiovascular Flow Lab using Doppler ultrasound velocity measurements and MR angiogram imaging of the left arm vessels. A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of the patient’s vasculature was created (Image 4), allowing prediction of the minimum necessary tubal diameter and length of the left subclavian band to achieve reduced distal flow (Image 5). This information was provided to the surgical team.

Image 4. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Model:

Model used to determine appropriate sizing for the subclavian artery band. Initial flow dynamics showeds 73% of total cardiac output traveling to the left subclavian (Qtot = total cardiac output; Qlsa = left subclavian artery flow; Qda = descending aortic flow; Qba + lca = flow to the brachiocephalic artery and left carotid artery).

Image 5. Graph of CFD Modeling:

Indicates reduction of the internal diameter of the left subclavian artery to 3 mm was required to decrease subclavian arterial flow and consequently improve descending aortic and brachiocephalic arterial flows.

4. Management

Initial management was through a multidisciplinary approach with the vascular anomalies team, nutrition, cardiology, interventional radiology, orthopedics and genetics. The primary focus was on treating his heart failure related to this large vascular anomaly. He was therefore continued on diuretics and fortified feeds. However, despite medical management he developed increased work of breathing and liver distension, findings consistent with congestive heart failure. He was therefore discussed at multidisciplinary conference and agreement was reached to proceed with surgical banding of his left subclavian artery; a decision based on the CFD modeling and a report of successful arterial banding in a similar case involving the right arm [1]. Notably, the patient reported by Behr et al. had a positive family history of capillary malformations and an inherited RASA1 mutation was identified.

A posterolateral thoracotomy was performed, the pleural space was entered via the fourth intercostal space and the left subclavian artery was exposed. Muscle, skin, lymphatic, venous and arterial tissues were collected for genetic testing. A 3.5 mm Gore-Tex tube was placed around the left subclavian artery at its mid aspect and tied down over a distance of 1 cm to obtain a luminal diameter of approximately 2.5–3 mm. He was extubated in the operating room and transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit. Intraoperatively, he developed hypertension which was attributed to the change in the flow dynamics and less “steal” from the left arm. He was managed with antihypertensive medications and he was discharged home on post-operative day 6.

5. Genetics

Because of the segmental distribution of capillary malformation, no blood-based DNA sequencing was performed. Fibroblasts were cultured from a skin biopsy from the capillary malformation over left upper arm, and the following genes were sequenced on an exome backbone at mean depth of 250X: EPHB4, GNAQ, KRAS, MAP2K1, RASA1. No mutations were identified. Deletion/duplication testing of RASA1 and EPHB4 from this DNA was also negative. DNA sequencing from a fresh skin biopsy that was not cultured, using a high coverage targeted panel (VANSeq, seattlechildrenslab.testcatalog.org/show/VANseq-1) identified a mutation in MAP2K1.

6. Post-operative follow-up

Following surgery, over the course of several months the size of the left arm gradually improved. The parents noted that he more easily fit his arm into clothes. They also noted improved use of the left arm. On examination, the violaceous, nodular skin patches improved to smooth, salmon-colored lesions. The previously noted arm bruits were no longer audible. He was quickly weaned off diuretics and his antihypertensive medications were slowly tapered off. Doppler ultrasound and echocardiographic imaging showed prominent, but improved venous flow from the left arm and normalization of the left ventricular size. A repeat MRI showed 22% of the cardiac output distributed to the left arm, compared to 73% preoperatively.

7. Discussion

Parkes Weber syndrome is a rare vascular anomly comprised of both fast-flow (aterial/arteriovenous) and slow-flow (capillary/venous) lesions [2]. This combination of fast-flow and slow-flow malformations is what distinguishes Parkes Weber syndrome from other vascular anomalies, namely Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, which is a pure low-flow condition. It was first idenitifed as a unique disease in 1907 when it was described in two patients by Frederick Parkes Weber [3]. His theory that this represented a novel diagnosis has been validated by recent genetic testing that has identified a mutation in the RASA-1 gene in patients with Parkes Weber syndrome [4,5]. This combination of capillary malformation, venous malformation, arteriovenous malformations and lymphatic malformations in a single extremity leads to severe limb overgrowth. Parkes Weber syndrome has a worse prognosis since the high-flow lesions put patients at risk for congestive heart failure or limb ischemia, occasionally requiring embolization or even amputation, typically in early adulthood [6,7].

In our patient, the concern shortly after diagnosis pertained to early onset symptoms of congestive heart failure. This presented as tachypnea, poor weight gain and liver distension and was underlined by the chest radiograph (pulmonary edema and cardiomegaly) and echocardiogram (left atrial and left ventricular dilation). While initial genetic testing was negative for a RASA-1 mutation, a clinical diagnosis of Parkes Weber syndrome was made by the combination of fast-flow and slow-flow vascular malformations. Subsequent, higher-coverage genetic testing on uncultured tissue taken at the time of surgery found a mutation in the MAP2K1 gene. Further details of this mutation will be published separately.

The MAP2K1 gene codes for the MEK1 protein, which is a component of the RAS/MAPK signalling pathway [8]. Mutations in this gene are found in various cancers and extracranial AVMs. The identification of this mutation offers a potential therapy as MEK1 inhibitors are currently used in oncology where they may play a role in helping endotheial cells differentiate into capillary beds.

The rarity of this diagnosis in such a young patient and the early onset of symptoms required a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to his management with the dual goals of addressing his symptoms of congestive heart failure and saving his extremity. The use of CFD modeling allowed us to refine a novel management strategy initially reported by Behr et al. [1]. Using computer modeling, we were able to predict the appropriate length and luminal diameter in the left subclavian artery to appropriately restrict the downstream flow. Those recommendations were incorporated by the cardiothroacic surgical team and the success of that prediction was apparent when, immediately after left subclavian banding, the arterial pressures dramatically increased. The flow previously shunted through the arterial venous malformations was now distributed to the rest of the body resulting in the hemodynamic changes observed intraoperatively and at follow-up. Subsequent imaging has shown a fraction of the blood volume distributed to the left upper extremity and the result has been resolution of his congestive heart failure and decreased left arm edema, now one year from his subclavian banding. The long-term implications of this approach remain uncertain and the patient will therefore continue to have close outpatient follow-up. The identification of the MAP2K1 mutation offers an alernate management strategy using MEK1 inhibitors should symptoms return or should the CM-AVMs progress.

8. Conclusions

Parkes Weber syndrome is a rare diagnosis involving fast-flow and slow-flow lesions that can lead to early symptoms of congestive heart failure. Occasionally amputation is required to manage the sequelae from the lesions. Using CFD modeling we were able to offer an alternative surgical management strategy, one that has thus far proven successful. The identification of a mutation in MAP2K1 offers the potential for medical therapies should his disease progress in the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health under National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant 2R01HL130996 (to JTB).

Abbreviations

- CFD

computational fluid dynamics

Footnotes

Consent

The case was reviewed with Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. Consent to publish the case report was obtained.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Behr GG, et al. CM-AVM syndrome in a neonate: case report and treatment with a novel flow reduction strategy. Vasc Cell 2012;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Branzic I, et al. Parkes Weber syndrome—diagnostic and management paradigms: a systematic review. Phlebology 2017;32(6):371–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Parkes Weber F, Liang MG. Angioma: formation in connection with hypertrophy of limbs and hemi-hypertrophy. Br J Dermatol 1907;19:231–5. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Eerola I, et al. Capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2003;73: 1240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Vikkula M. RASA1: variable phenotype with capillary and arteriovenous malformations. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2005;15:265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Berger TM, Caduff JH. Hemodynamic observations in a newborn with Parkes-Weber syndrome. J Pediatr 1999;134:513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marzban S, et al. Embolization techniques for high-flow arteriovenous malformations in parkes-weber. J Vasc Surg 2018:e208. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Couto JA, et al. Somatic MAP2K1 mutations are associated with extracranial arteriovenous malformation. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]