To The Editor: Pressure injuries, a common skin finding that significantly impacts the quality of life in hospitalized patients, are associated with increased mortality and result in increased healthcare costs.1 In COVID-19 infection, pressure injury sites are associated with purpuric lesions.2 This study investigates the epidemiology and laboratory findings of these lesions to elucidate their etiology.

From March 12, 2020, to May 31, 2020, at a single institution, 1216 adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were retrospectively reviewed. A centralized clinical data registry with search functionality combined with a manual chart review identified patients with skin lesions. At least 2 dermatologists, with a third dermatologist for adjudication, evaluated patient records for pressure injury and identified the presence or absence of purpuric features.

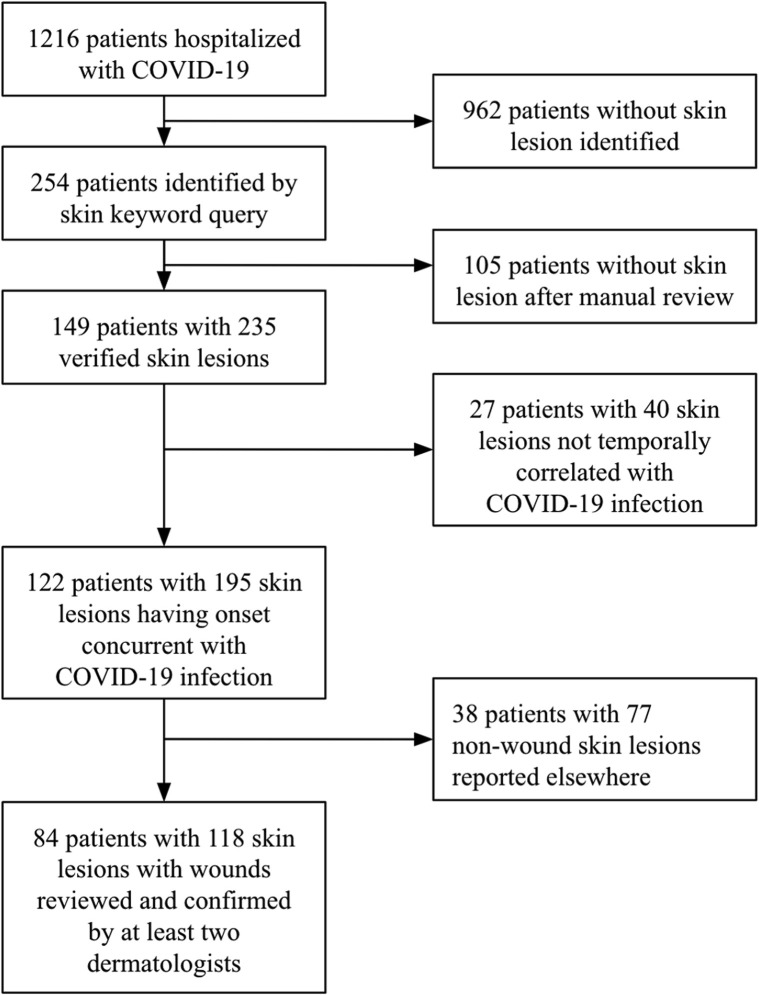

Altogether, 84 patients (6.9%) with 118 pressure injuries having onset concurrent with COVID-19 hospitalization were identified (Fig 1 ). The dermatologists were aided by photographs of 73.8% (n = 62/84) of the patients. The pressure injuries were associated with a prolonged length of stay (mean of 37.3 days) and high rates of endotracheal intubation (81.9%) (Table I ). A portion of the patients (32.5%; n = 27/83) had pressure injuries with purpuric features. Laboratory values related to coagulopathy at lesion onset did not differ between patients with and without purpura, with the exception of D-dimer values, which were higher (P = .016) for patients with purpuric features (Supplemental Table I; available at https://doi.org/10.17632/vkzxr32ffr.1).

Fig 1.

Flowchart of patient selection for constructing the study and control groups. Skin lesions were categorized as concurrent with COVID-19 hospitalization when onset occurred within 14 days prior to admission and up to discharge.

Table I.

Comparison of patients with nonpurpuric and purpuric pressure injuries

| Characteristic | Patients with nonpurpuric pressure injury∗ (n = 61) | Patients with purpuric pressure injury∗ (n = 27) | Total patients with pressure injury (n = 84) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion evaluation | ||||

| Day of injury onset since admission (mean ± SD) | 11.2 ± 8.0 | 14.3 ± 10.0 | 12.0 ± 9.0 | .25 |

| Dermatology consultation obtained | 4 (6.6%) | 7 (25.9%) | 10 (11.9%) | .0070 |

| Photographs obtained | 40 (65.6%) | 25 (92.6%) | 62 (73.8%) | .0075 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 60.9 ± 15.6 | 63.6 ± 14.8 | 61.9 ± 15.3 | .49 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 45 (73.7%) | 21 (77.8%) | 61 (73.5%) | .54 |

| Female | 16 (26.2%) | 6 (22.2%) | 22 (26.5%) | |

| Patient past medical history | ||||

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 31.8 ± 7.9 | 33.6 ± 9.6 | 32.1 ± 8.3 | .25 |

| Hypertension | 25 (40.9%) | 15 (55.6%) | 38 (45.9%) | .21 |

| Diabetes | 25 (40.9%) | 14 (51.9%) | 36 (43.4%) | .28 |

| Chronic heart disease | 5 (8.2%) | 1 (3.7%) | 6 (7.2%) | .39 |

| Chronic lung disease | 7 (11.5%) | 6 (22.2%) | 12 (14.5%) | .16 |

| Stroke/cerebrovascular accident | 3 (4.9%) | 2 (7.4%) | 5 (6.0%) | .71 |

| Smoking/cigarette use | 24 (39.3%) | 15 (55.6%) | 36 (42.9%) | .16 |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Length of stay in days (mean ± SD) | 36.5 ± 20.4 | 42.3 ± 25.1 | 37.3 ± 21.9 | .15 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 52 (85.2%) | 24 (88.9%) | 71 (85.6%) | .55 |

| Death | 13 (21.0%) | 4 (14.8%) | 17 (20.5%) | .37 |

| Treatment course | ||||

| Endotracheal intubation | 50 (81.9%) | 23 (85.2%) | 68 (81.9%) | .59 |

| Orogastric/nasogastric intubation | 48 (78.6%) | 21 (77.8%) | 64 (77.1%) | .92 |

| Urinary catheterization | 52 (85.2%) | 24 (88.9%) | 71 (85.5%) | .55 |

| Rectal intubation | 49 (80.3%) | 22 (81.5%) | 66 (79.5%) | .76 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 11 (18.0%) | 3 (11.1%) | 12 (14.5%) | .55 |

| Clinical course | ||||

| Cerebrovascular accident | - | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | - |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5 (8.2%) | 1 (3.7%) | 6 (7.2%) | .39 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 5 (8.2%) | 3 (11.1%) | 8 (9.6%) | .76 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 2 (3.3%) | - | 2 (2.4%) | - |

| On therapeutic anticoagulation at onset of first injury | 12 (19.7%) | 8 (29.6%) | 18 (21.4%) | .26 |

BMI, Body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

4 patients had multiple pressure injuries of which some had purpuric features and others had only nonpurpuric features. Values for these patients are tabulated in both columns.

Statistical testing is performed comparing patients having pressure injuries with purpuric features to patients having pressure injuries none of which had purpuric features.

The incidence of pressure injury in this study (6.9%) is comparable to previous estimates of 5%-15% of hospitalized patients, depending on clinical context.1 With respect to COVID-19 hospitalization specifically, the especially tenuous respiratory status in these critically ill patients frequently interfered with standard preventative measures to turn patients for inspection and pressure offloading.1 , 3 Placing patients in a prone position has been demonstrated to reduce the development of pressure injuries and is associated with improved outcomes in the setting of a poor respiratory status.4 However, this study discovered 36 pressure ulcers (30.5%) occurring on the face, likely resulting from proning, emphasizing specific challenges affecting patients with COVID-19 and the importance of prophylactic measures to prevent these injuries in proned patients.

This study only found elevated D-dimer levels in patients with purpuric pressure injuries, corroborating previous reports of elevation of fibrin and fibrinogen degradation products in COVID-19.5 Thromboembolic events and abnormalities in other markers of coagulation were not found to be more common in patients with purpuric pressure injuries within our cohort. Biopsies were obtained in 4 patients and previously reported as exhibiting epidermal and eccrine gland necrosis, supportive of pressure-induced injury, with fibrin thrombi in superficial dermal vessels only.2 These findings suggest that purpuric features of pressure injuries are less likely indicative of occult pathology resulting from COVID-19 infection and emphasize the usual prevalence of pressure injuries in critically ill patients, highlighting the importance of identifying risk factors, encouraging preventative measures, and reinforcing the known standard of care. Taking steps to address predisposing factors in hospitalized COVID-19 patients is essential in preventing these lesions and improving outcomes.1 , 3

The authors would like to thank the clinicians who cared for these patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and created the documentation necessary to make this study possible.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Authors Rrapi and Chand contributed equally to this article.

Funding Sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Mervis J.S., Phillips T.J. Pressure ulcers: pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chand S., Rrapi R., Lo J.A., et al. Purpuric ulcers associated with COVID-19 infection: a case-series. JAAD Case Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang J., Li B., Gong J., Li W., Yang J. Challenges in the management of critical ill COVID-19 patients with pressure ulcer. Int Wound J. 2020;17(5):1523–1524. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L., Li R., Wu Z., et al. Therapeutic strategies for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00661-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connors J.M., Levy J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033–2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]