Abstract

In the context of the United States of America (U.S.), COVID-19 has influenced migrant experiences in a variety of ways, including the government's use of public health orders to prevent migration into the country and the risk of immigrants contracting COVID-19 while in detention centers. However, this paper focuses on barriers that immigrants of diverse statuses living in the U.S.—along with their families—may face in accessing health services during the pandemic, as well as implications of these barriers for COVID-19 prevention and response efforts. We report findings from a scoping review about immigration status as a social determinant of health and discuss ways that immigration status can impede access to health care across levels of the social ecology. We then develop a conceptual outline to explore how changes to federal immigration policies and COVID-19 federal relief efforts implemented in 2020 may have created additional barriers to health care for immigrants and their families. Improving health care access for immigrant populations in the U.S. requires interventions at all levels of the social ecology and across various social determinants of health, both in response to COVID-19 and to strengthen health systems more broadly.

Keywords: Immigrant health, Social determinants of health, Social ecological model, Health policy, Health care access, COVID-19

Introduction

In the United States of America (hereafter referred to as the U.S.), the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced migration in a variety of ways. Citing public health concerns, both the United States Department of Homeland Security (2020) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020a) enacted restrictions on persons entering the country. Additionally, a series of presidential proclamations barred entry to persons from specific geographic regions, as well as groups of migrants more generally (United States Department of State, 2021) citing both health and economic objectives. Scholars and activists have critiqued these measures for restricting the movement of populations and denying legal processes to vulnerable groups, including unaccompanied children and asylum-seekers (Garcini et al., 2020; Ramji-Nogales and Goldner Lang, 2020; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020). Also, individuals held by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in detention centers have been found to be at heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 as compared to the larger U.S. population, even after ICE stated that it implemented mitigation measures (Erfani et al., 2020).

While the health implications of policies related to migration and immigrant detention raise important questions, this paper focuses on ways the COVID-19 pandemic intersects with health care access among immigrant populations already residing in the U.S. Highlighting barriers to health care for immigrant communities during COVID-19 is particularly important because the pandemic has underscored health disparities among marginalized groups in the U.S., including immigrants and communities of color (Barry et al., 2020; Cholera et al., 2020; Choo, 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Page et al., 2020; Roberts and Tehrani, 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2021; Rollston and Galea, 2020; van Dorn et al., 2020; Williams, 2020). As of December 4, 2020, CDC reported a total of 14,041,436 cases of COVID-19 and 275,386 deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b). Infection rates and mortality rates among Black, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Latinx populations, as well as among communities of color more broadly, are higher as compared to those of white populations, and these groups are over-represented in cases and deaths as compared to their representation in the larger population (Artiga et al., 2020; The COVID Tracking Project, 2020). In addition to these reported COVID-19 cases, many more cases remain unreported. Therefore, these reported statistics do not give a clear picture about the pandemic's effect on immigrants and their families living in the U.S. These data—and the gaps in these data—led our team to reflect on our recent research about immigration and health in new ways.

This paper discusses immigration status as a social determinant of health, along with direct and indirect ways several COVID-19 prevention and response efforts excluded various immigrant groups. In particular, this paper focuses on barriers that immigrants of diverse statuses living in the U.S.—along with their families—may face in accessing health services during the pandemic, as well as implications of these barriers for COVID-19 prevention and response efforts. We report findings from a scoping review about immigration status as a social determinant of health, and discuss ways that immigration status can impede access to health care across levels of the social ecology. We then develop a conceptual outline to explore how changes to federal immigration policies and COVID-19 federal relief efforts implemented in 2020 may have created additional barriers to health care for immigrants and their families.

Methodology

A social determinant of health is a social factor that impacts health outcomes (United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019; World Health Organization, n.d.). In Summer 2019, our multi-disciplinary research team conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed research and practitioner-focused gray literature to better understand the role of immigration status as a social determinant of health. Our methodology aligned with the framework from Arksey and O'Malley (2005) for a scoping study, which is a type of literature review that synthesizes diverse sources on a specific topic and disseminates key findings in a timely manner to inform broader research, policy, and practice initiatives. A detailed description of the methodology has been reported elsewhere (Rodriguez et al., 2021). After the COVID-19 pandemic began, we revisited the scoping review and added resources related to COVID-19 prevention and response efforts.

Immigration status as a social determinant of health in the U.S.

The decision to migrate and the migration experience itself has implications for one's health. Of particular significance is one's immigration status upon entering into the U.S. because it has implications for social determinants of health. Immigration-related factors that can influence health include stressors both before and after migration, the ways laws and policies influence access to benefits and services across different legal classifications, and through the relationship between immigration and factors like living environments, working conditions, and enforcement activities (Castañeda et al., 2015; Chang, 2019; Cholera et al., 2020; Cohen et al., 2017; Derr, 2016; Diaz et al., 2017; Dulin et al., 2012; García, 2012; Hall and Cuellar, 2016; Ko Chin, 2018; Lee and Zhou, 2020; Majumdar and Martínez-Ramos, 2016; Martinez et al., 2015; Morey, 2018; Patler and Laster Pirtle, 2017; Schuch et al., 2014; Shor et al., 2017; Siemons et al., 2017; Stimpson et al., 2012; Sudhinaraset et al., 2017; Rodriguez, McDaniel, and Bisio, 2019; Rodriguez, Rodriguez, and Zehyoue, 2019; Vargas et al., 2017; Vargas and Ybarra, 2017; Venkataramani et al., 2017; Yeo, 2017). Factors like country of origin, destination country, race/ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, and immigration status influence health outcomes both before and after migration (Diaz et al., 2017; Shor et al., 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2021).

In 2019, about 45.8 million U.S. residents were born in countries other than the U.S., representing about 14% of the country's population overall (United States Census Bureau, 2020a). Residents who were born outside of the U.S. represented diverse regions of origin: 52% of immigrants originally migrated from Latin America and the Caribbean, 30% from Asia, 10% from Europe, and 8% from all other regions of the world (United States Census Bureau, 2020b). The government has various classifications to describe residents born in countries other than the U.S. For example, at the time of the scoping review, the government distinguished between foreign-born individuals with governmental authorization to reside and to be employed in the U.S.; foreign-born individuals with temporary authorization to be in the U.S. (which may or may not have included permission to work); and “deportable aliens,” or foreign-born individuals without governmental authorization to enter the U.S., or who remained in the U.S. after their initial authorized period (United States Department of Homeland Security, 2018).

Findings from our scoping review indicated that differences between such immigration classifications influenced many aspects of health among immigrant communities. Specific to undocumented immigrants, Martinez et al. (2015) identified two main mechanisms through which laws and policies in various countries are hypothesized to impact health outcomes: (1) by regulating access to resources like health insurance and health care; and (2) by influencing the overall environment in which immigrants make decisions about their health. While Martinez et al. (2015) evaluated experiences of undocumented immigrants specifically, other sources in our scoping review found that immigration laws impacted health and well-being for both immigrants and their family members across immigration status classifications, as well as for residents who are members of racial and/or ethnic minority groups (Majumdar and Martínez-Ramos, 2016; Morey, 2018; Vargas et al., 2017; Vargas and Ybarra, 2017). For example, Vargas et al. (2017) found that both Latino/a citizens and noncitizens who lived in states with a high number of immigration-related laws had decreased odds of reporting optimal health as compared to Latino/a respondents in states with fewer immigration-related laws. Regarding families in which members have different immigration statuses, Vargas and Ybarra (2017) compared parental reports of child health status across three different groups of Latino/a families: families in which the parent was undocumented and the child was a U.S. citizen, families in which the parent was a Legal Permanent Resident and the child was a U.S. citizen, and families in which the parent and child were both U.S. citizens. Vargas and Ybarra (2017) found that the undocumented parents were less likely to report optimal health for their child who was a citizen as compared to other families in the sample.

Such laws and policies also make the U.S. health care system complicated to navigate (Parmet et al., 2017). A detailed analysis of different laws in each state and how these laws impede health care access for immigrants with different legal classifications is outside the limits of this paper. However, as members of our team have written about previously, the complexity of local, state, and federal laws in the U.S. results in inconsistent immigration-related policies in different geographic areas and a diversity of barriers and facilitators to immigrant integration around the U.S. (McDaniel et al., 2017, McDaniel et al., 2019, McDaniel et al., 2019, Rodriguez et al., 2019).

One mechanism through which immigration status functions as a social determinant of health is its connection to health insurance eligibility (Barry et al., 2020; Castañeda et al., 2015; Garfield et al., 2019; Duncan and Horton, 2020; Ko Chin, 2018; Martinez et al., 2015; Morey, 2018; Parmet et al., 2017; Stimpson and Wilson, 2018; Viladrich, 2012; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020). Health insurance is considered an “enabling factor,” or a resource that increases the availability of health services for individuals (Andersen, 1995; Lee and Matejkowski, 2012; Yeo, 2017).

Federal laws and policies determine some aspects of public health insurance eligibility related to immigration status. For example, the 1996 Personal Responsibility Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) restricted authorized immigrants’ access to public benefits like Medicaid during the first five years of their residency in the U.S. (Hall and Cuellar, 2016; Ko Chin, 2018; Lee and Matejkowski, 2012; Parmet et al., 2017; Stimpson et al., 2012; Viladrich, 2012; Yeo, 2017). While undocumented immigrants had not been eligible for federal benefits before PRWORA, the law explicitly excluded them from participating in federal programs, and it restricted funding to local programs that previously supported health care for unauthorized immigrants (Viladrich, 2012). Then the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 replicated several immigration-related policies from PRWORA, including a five-year waiting period for most authorized adult immigrants to be able to enroll in Medicaid and the exclusion of undocumented immigrants in any federal insurance programs, including public health insurance options, health insurance exchanges, and tax credits (Garfield et al., 2019; Parmet et al., 2017; Stimpson and Wilson, 2018).

In 2018, almost one-quarter (23%) of authorized immigrants and almost half (45%) of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. did not have insurance, making noncitizens significantly more likely to be uninsured as compared to citizens (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). Among undocumented immigrants, low insurance coverage can be attributed in part to ineligibility for many public health insurance options and over-representation in low-paying jobs that are less likely to have access to employee-sponsored health insurance (Garfield et al., 2019; Parmet et al., 2017).

While limited access to health insurance coverage is one barrier to health care for many immigrant populations, the literature identified other barriers as well. Like social determinants of health frameworks, social ecological models posit that an individual's health outcomes cannot be isolated from larger, interconnected social systems that encompass individual, relationship, community, and societal levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Dahlberg and Krug, 2002; Golden and Earp, 2012; McLeroy et al., 1988; Stokols, 1992, 1996). Social ecological frameworks appeared in many of the sources included in our scoping review because of the ways immigration status influences immigrants’ access to health care at each different socioecological level (Derr, 2016; Earnest, 2006; Edberg et al., 2017; García, 2012; Hacker et al., 2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018; Siemons et al., 2017).

As examples, Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016) are two robust literature reviews that presented similar barriers to health care access for immigrant populations, but used different categories within their social ecological frameworks. The first review by Hacker et al. (2015) focused on barriers to health care services for populations of undocumented immigrants in various countries that appeared in English-language sources in PubMed from 2005−2015 (p. 176). The purpose was to identify barriers to care for immigrant populations including but not limited to legal restrictions, as well as to classify different strategies to address these barriers (Hacker et al., 2015). The second review by Derr (2016) focused on mental health care services in the U.S. and included studies with populations representing different immigration classifications and different countries/regions of origin that were published in seven different databases from 1999−2013. The purpose was to identify differences and commonalities in immigrant experiences regarding mental health services that could inform increased health equity and quality of mental health services for immigrant populations in the U.S. (Derr, 2016, pgs. 265–266).

We highlight these two literature reviews for several reasons. They were sources that we found during our original scoping review, and they were published only one year apart. They had a shared purpose of identifying barriers to care for immigrants across the social ecology, though the populations included in each review differed. Additionally, both reviews were published within the last five years, and so their findings also were relevant to understanding potential barriers to care for immigrant communities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the barriers identified by both Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016). Though these two studies identified many of the same barriers for immigrants seeking care, they differed in both the social ecological models that they used and the levels at which they categorized specific barriers. Hacker et al. (2015) divided barriers into three levels: policy-level barriers, system-level barriers, and individual-level barriers. Derr (2016) reported two levels of barriers: the structural level and the cultural level. Both Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016) identified barriers such as lack of insurance, experiencing discrimination, and resource constraints like concerns about missing work, lack of transportation, language barriers, and absence of provider cultural competency. Additionally, both Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016) found that fear of deportation, high cost of care, and lack of knowledge about resources and the health care system were barriers for immigrants accessing care. Derr (2016) also identified several barriers to immigrants accessing mental health services that were not identified in the review by Hacker et al. (2015), such as lack of collaboration between social services and churches, and challenges with acculturation. At the same time, Hacker et al. (2015) categorized enforcement/deportation, communication, financial resources, and familiarity with the health care system at the individual level. Derr (2016) categorized these same barriers at the structural level. Derr (2016) did not employ an individual-level category in the review, but rather divided findings into cultural barriers or structural barriers as a way to highlight the critical role of barriers to care beyond the individual level (A.S. Derr, personal communication, November 12, 2020). We point out these differences in social ecological models and levels not to critique or favor one representation over the other, but rather to highlight the ways different conceptualizations of the same barrier may influence how public health efforts might address it.

Table 1.

Different Classifications of Barriers to Care for Immigrant Populations, as identified by Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016).

| Hacker et al. (2015)1 Barriers to Overall Health Care Access Among Undocumented Immigrants in Several Countries N = 66 | # (%) of Articles1 | Derr (2016)2 Barriers to Mental Health Care Access Among Documented & Undocumented Immigrants in the U.S. N = 23 | # (%) of Articles2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level1 | Barrier | Description | Level2 | Barrier | Description | ||

| Policy Level | Laws | Legal barriers, such as laws precluding insurance eligibility | 50 (76) | Structural Level | Laws | No insurance | 4 (17) |

| Documentation Requirements |

Requiring documentation to access health care services; challenges for undocumented parents seeking to access care for their authorized children | 18 (27) | Documentation Requirements |

Anxiety among undocumented immigrants that documentation would be required to access health services | 1 (4) | ||

| System Level | Resource Limitations |

Employment conflicts, lack of transportation, and limited health care capacity (nonexistent or limited translation services; provider cultural competency; clinical funding cuts) | 24 (36) | Resource Limitations |

Apprehension of being absent from work, lack of transportation and/or inaccessibility, and limited health care capacity (such as lack of provider cultural competency and gender of provider). | 7 (30) | |

| Discrimination | Documentation status/nativity | 22 (33) | Discrimination | Structural Discrimination | 1 (4) | ||

| Complexity of Medical System/ Bureaucracy |

Bureaucratic requirements for immigrants and for providers that prevent access of/delivery of care | 17 (26) | Complexity of Medical System/ Bureaucracy |

Long wait required | 3 (13) | ||

| Individual Level | Enforcement/Deportation | Fear of authorities being contacted/fear of deportation | 43 (65) | Enforcement/ Deportation |

Fear of deportation among undocumented immigrants | 4 (17) | |

| Communication | Challenges of communication with providers, including language and cultural differences; concern about being understood | 24 (36) | Communication | Language barriers | 9 (39) | ||

| Financial Resources |

Concerns about ability to pay for services | 30 (45) | Financial Resources |

High price of services | 8 (35) | ||

| Not Familiar with Medical System |

Not having knowledge about how the health care system functions or how to navigate it; lack of awareness about services available/rights to health care | 22 (33) | Not Familiar with Medical System |

Lack of familiarity/understanding about available resources | 8 (35) | ||

| Shame/ Stigma | Concerns about feeling shame in accessing services and experiencing stigmatization for doing so | 7 (11) | Cultural Level | Shame/Stigma | Sigma related to cultural norms about mental health | 6 (39) | |

Source: Hacker, K., Anies, M, Folb, B.L., and Zallman, L. (2015). Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: A literature review. Risk management Healthcare Policy, 8:175–183.

The overall format for this table was also adapted from Table 1 (p. 177) from this source.

Source: Derr, A. S. (2016). Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 265. The review includes 62 articles in total, but only 23 were included in the discussion of barriers. Other cultural-level barriers that Derr (2016) identified, but are not included in Table 1 include: cultural norms related to mental illness (17%), preference for other types of services (9%), lack of trust in providers (9%), reliance on self or family (9%), and challenges with acculturation (4%); additional structural barriers not included in Table 1 include lack of collaboration between services and churches (4%) competing health demands (4%) and other barriers (4%) (p. 268).

Implications for health care access for immigrant communities in the U.S. during COVID-19

As discussed above, our team considered how framing immigration status as a social determinant of health might inform COVID-19 prevention and response efforts. In this section, we synthesize various sources to better understand how changes to federal immigration policies and COVID-19 federal relief efforts implemented during 2020 may have created additional barriers to health care for many immigrants in the U.S.

Additional sources we found related to COVID-19 reported that federal immigration policies may have interacted with COVID-19 related efforts to result in both regulatory and environmental barriers to health care for immigrants and their family members (Cholera et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Duncan and Horton, 2020; National Immigration Law Center, 2020; Page et al., 2020; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020). For example, while federal initiatives like the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act from 2020 and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) also from 2020 expanded free COVID-19 testing for uninsured individuals, they did not explicitly cover treatment expenses (National Immigration Law Center, 2020). While funds were made available to reimburse providers for treatment of the uninsured, the program was opt-in and not all patients were aware of such funding or which providers participated (Schwartz and Tolbert, 2020). Additionally, the Recovery Rebate sent to taxpayers under the CARES Act required a Social Security Number, and thereby excluded many immigrant households and mixed-immigration status households who used Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (National Immigration Law Center, 2020). In this way, being uninsured and undocumented limited access to both COVID-19 treatment services and to economic relief measures related to the pandemic. Furthermore, the federal legislation did not explicitly ban immigration enforcement actions from happening at medical facilities (National Immigration Law Center, 2020). Though ICE stated that it would not implement enforcement operations at health care facilities except in "extraordinary" circumstances, it did not define what constituted such circumstances (United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020).

Inequitable health policies towards immigrants also create distrust in public health systems (Duncan and Horton, 2020; Parmet et al., 2017). For this reason, other changes to federal immigration policies also could have influenced immigrants’ access to health care during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In August 2019, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued the final rule for Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds, which it started implementing on February 24, 2020 (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2020). This “public charge rule” stated that the government could deny visas and lawful permanent resident status to noncitizens who had used public benefits for more than 12-months within any 36-month period while residing in the U.S., and/or who were deemed likely to use public benefits in the future (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2020). After the COVID-19 pandemic began, the government reported that it would not consider testing, treatment, or preventative care associated with COVID-19 under the public charge rule (United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2020). However, the rule still may have created a barrier for immigrant families concerned that their future immigration claims would be negatively impacted by accessing health services and other public benefits (Clark et al., 2020; Duncan and Horton, 2020; National Immigration Law Center, 2020; Page et al., 2020; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020). Through creating distrust, inequitable policies towards immigrants may generate additional barriers to COVID-19 prevention and response efforts.

Building on the work by Hacker et al. (2015) and Derr (2016), our team reflected that some policies transcend across social ecological levels, meaning that they present challenges or facilitators to health care access at the policy, system, and individual levels. Though literature regarding social ecological models generally recognizes the interactions that exist between the different levels represented (for example Stokols, 1992, Stokols, 1996), the sources that we found in our scoping review consistently assigned each specific barrier or facilitator on one level or another. The models may not visually represent ways that elements at each level are connected with each other, as in for example, the ways system-level discriminatory practices may lead to individual-level experiences of stigma. Additionally, several different policies can also intersect with each other to create additional barriers throughout the social ecology (McDaniel et al., 2017, McDaniel et al., 2019, McDaniel et al., 2019, Rodriguez et al., 2019).

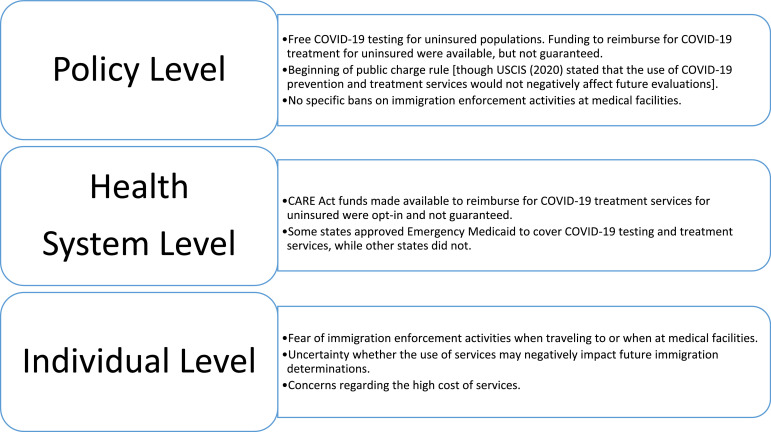

To illustrate this, Fig. 1 provides a conceptual outline of how three federal policies that were in passed or in effect during 2020—the final rule for Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds, the CARES Act, and FFCRA—may have influenced access to health care, public health insurance eligibility, and health seeking behaviors for uninsured immigrants and their families during this time in the COVID-19 pandemic (Cholera et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Derr, 2016; Duncan and Horton, 2020; Hacker et al., 2015; Page et al., 2020; National Immigration Law Center, 2020; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020). We used the levels presented in Hacker et al. (2015) to identify potential impacts across the social ecological model.

Fig. 1.

Concept Map of U.S. Federal Policies related to Uninsured Immigrant Populations’ Health Care Access in 2020 during COVID-19. This conceptual map theorizes ways three federal laws and policies implemented in 2020—(1) The Final Rule for Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds; (2) the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act; and (3) the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)—may have influenced access to health care and health-seeking behaviors among uninsured immigrants and their families across levels of the social ecology during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This conceptual map builds from previous work by Cholera et al. (2020); Clark et al. (2020); Derr (2016); Duncan and Horton (2020); Hacker et al. (2015); Page et al., 2020; National Immigration Law Center (2020); Schwartz and Tolbert (2020); Wilson and Stimpson (2020).

At the policy level, legislation provided funding for testing of uninsured populations, and funding for reimbursement for treatment services to the uninsured was not guaranteed. This policy-level barrier could then impact health systems because reimbursement for treatment may not have been assured. Additionally, uninsured individuals may have decided not to seek needed services due to concerns that they would not be able to pay for them. Also, policies like the public charge rule may have increased barriers to care because of increased fear among immigrants that accessing services would block future opportunities to adjust their immigration status, despite assurances from USCIS (2020) that services associated with COVID-19 would not be considered. It should be noted that Fig. 1 does not represent several additional layers of complexity related to location-specific laws.

Much public health literature that utilizes social ecological models supports comprehensive approaches to health promotion at various levels of the social ecology (for example, Dahlberg and Krug, 2002; Earnest, 2006; Edberg et al., 2017; García, 2012; Golden and Earp, 2012; Siemons et al., 2017; Stokols, 1992, Stokols, 1996; Williams and Purdie-Vaughns, 2016). As Fig. 1 illustrates, certain barriers to care that generally appear in social ecological models under one level (i.e., policy) simultaneously impact other levels as well (i.e., systems and individual levels). The ways that immigration status influences access to care across all social ecological levels represent another reason that focusing on one level in isolation of others is unlikely to be effective, especially during a public health emergency.

In the context of COVID-19 in which a significant proportion of the population may need to access health care services quickly and at the same time, the link between health insurance coverage and health care is significant for all populations, and especially among populations who may experience significant barriers to care. Additionally, immigrants—along with people of color more broadly—represent a significant proportion of essential workers in sectors such as health care, groceries, pharmacies, manufacturing, and agriculture (Gelatt, 2020). These concerns, along with the recognition that inclusive measures support the health and safety of all populations, underscore the need for more comprehensive prevention and response measures (Barry et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Duncan and Horton, 2020; Gelatt, 2020; National Immigration Law Center, 2020; Roberts and Tehrani, 2020; van Dorn et al., 2020; Wilson and Stimpson, 2020).

Conclusion

Framing immigration status as a social determinant of health underscores challenges many immigrants and their families face accessing health services. Laws and policies impact health outcomes for immigrants and their families across immigration and citizenship classifications through regulating access to resources like health insurance and health care, and through influencing the overall environment in which immigrants make decisions about health-seeking behaviors (Martinez et al., 2015; Majumdar and Martínez-Ramos, 2016; Vargas et al., 2017; Vargas and Ybarra, 2017). Such laws and policies contribute to structural racism by excluding certain racialized groups—like undocumented immigrants and others—from accessing health care and other services, which then leads to disparities in health outcomes (Barry et al., 2020; Gee and Ford, 2011; Ko Chin, 2018; Morey, 2018; Patler and Laster Pirtle, 2017). Tia Taylor Williams (2020), Director of the American Public Health Association's Center for Public Health Policy, writes that “Racism, not race” is the cause of such disparities, emphasizing that the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among communities of color and other marginalized groups is due to inequitable policies and treatment at the individual, community, and systems levels.

COVID-19 prevention and response efforts also must be receptive to the many diverse experiences across and between immigrant communities in the U.S. Future research that engages larger diversities of racial/ethnic immigrant communities is necessary to have a more complete understanding of the health needs of immigrant communities. Future research may also consider how to visually represent in a model the many different U.S. legal classifications for immigration statuses—such as refugee, asylee, foreign-born individuals with and without authorization, and immigrants with Temporary Protected Status—and how different classifications influence immigrants’ access to care at different levels within social ecology frameworks. Improving health care access for immigrant populations in the U.S. will require interventions across levels of the social ecology and across varied social determinants of health, both in response to COVID-19 and for health systems more broadly.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Jessica Hill, Email: jhill245@students.kennesaw.edu.

Darlene Xiomara Rodriguez, Email: darlene.rodriguez@kennesaw.edu.

Paul N. McDaniel, Email: paul.mcdaniel@kennesaw.edu.

References

- Andersen R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artiga, S., Corallo, B., & Pham, O. (2020). Racial disparities in COVID-19: key findings from available data and analysis.Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-covid-19-key-findings-available-data-analysis/.

- Barry K., McCarthy M., Melikian G., Almeida-Monroe V., Leonard M., De Groot A.S. Responding to COVID-19 in an uninsured Hispanic/Latino community: testing, education and telehealth at a free clinic in providence. R I Med. J. 2020;103(9):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass: 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H., Holmes S.M., Madrigal D.S., Young M.D., Beyeler N., Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2015;36(1):375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Order suspending introduction of certain persons from countries where a communicable disease exists. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/order-suspending-introduction-certain-persons.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). CDC COVID data tracker: United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state. Retrieved from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.

- Chang C.D. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. 2019;49(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholera R., Falusi O.O., Linton J.M. Sheltering in place in a xenophobic climate: COVID-19 and children in immigrant families. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):1–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo E.K. COVID-19 fault lines. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1333. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30812-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E., Fredricks K., Woc-Colburn L., Bottazzi M.E., Weatherhead J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A.B., Grogan C.M., Horwitt J.N. The many roads toward achieving health equity. J. Health Polit. Policy & Law. 2017;42(5):739–748. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3940414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg L.L., Krug E.G. Violence−A global health problem. In: Krug E.G., Dahlberg L.L., Mercy J.A., Zwi A.B., Lozano R., editors. World Report On Violence and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Derr A.S. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Psychiatric Serv. 2016;67(3):265–274. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E., Ortiz-Barreda G., Ben-Shlomo Y., Holdsworth M., Salami B., Rammohan A., Krafft T. Systematic review and meta-analyses interventions to improve immigrant health. A scoping review. Eur. J. Public Health. 2017;27(3):433–439. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin M.F., Tapp H., Smith H.A., Urquieta de Hernandez B., Coffman M.J., Ludden T., Furuseth O.J. A trans-disciplinary approach to the evaluation of social determinants of health in a Hispanic population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):769–778. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan W.L., Horton S.B. Serious challenges and potential solutions for immigrant health during COVID-19. Health Affairs Blog. 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200416.887086/full/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Earnest J. Adolescent and young refugee perspectives on psychosocial well-being. Int. J. Human. 2006;3(5):79–86. doi: 10.18848/1447-9508/CGP/v03i05/41671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M.C., Cleary S.D., Andrade E.L., Evans W.D., Simmons L.K., Cubilla-Batista I. Applying ecological positive youth development theory to address co-occurring health disparities among immigrant Latino youth. Health Promot. Pract. 2017;18(4):488–496. doi: 10.1177/1524839916638302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erfani P., Uppal N., Lee C.H., Mishori R., Peeler K.R. COVID-19 testing and cases in immigration detention centers, April-August 2020. J. Am. Med. Association. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García J.I.R. Mental health care for Latino immigrants in the U.S.A. and the quest for global health equities. Psychosoc. Interv. 2012;21(3):305–318. doi: 10.5093/in2012a27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M., Domenech Rodríguez M.M., Mercado A., Paris M. A tale of two crises: the compounded effect of COVID-19 and anti-immigration policy in the United States. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2020;12:S230–S232. doi: 10.1037/tra0000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield R., Orgera K., Damico A. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer.https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gee G.C., Ford C.L. Structural racism and health disparities. Du Bois Rev. -Soc. Sci. Res. Race. 2011;8(1):115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt J. Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC: 2020. Immigrant workers: Vital to the U.S. COVID-19 response, Disproportionately Vulnerable.https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigrant-workers-us-covid-19-response Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Golden S.D., Earp J.A.L. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012;39(3):364–372. doi: 10.1177/1090198111418634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K., Anies M., Folb B.L., Zallman L. Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: a literature review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy. 2015;8:175–183. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S70173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E., Cuellar N.G. Immigrant health in the United States: a trajectory toward change. J. Transcul. Nurs. 2016;27(6):611–626. doi: 10.1177/1043659616672534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020). Health coverage of immigrants. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/.

- Ko Chin, K. (2018). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Retrieved from http://www.gih.org/Publications/ViewsDetail.cfm?ItemNumber=9331.

- Lee J.J., Zhou Y. How do Latino immigrants perceive the current sociopolitical context? Identifying opportunities to improve immigrant health in the United States. J. Soc. Policy. 2020;49(1):167–187. doi: 10.1017/S0047279419000163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Matejkowski J. Mental health service utilization among noncitizens in the United States: findings from the National Latino and Asian American study. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. 2012;39(5):406–418. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, D., & Martínez-Ramos, G.P. (2016). The impact of anti-immigrant environment on well-being of Latinos of Mexican descent in the U.S. Paper presented at the American Sociological Association,1–28. Retrieved from https://convention2.allacademic.com/one/asa/asa/index.php?click_key=1&PHPSESSID=j7pmpns5a7mu6t082t2r4mh3g3.

- Martinez O., Wu E., Sandfort T., Dodge B., Carballo-Dieguez A., Pinto R., Chavez-Baray S. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2015;(3):947–970. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel P.N., Rodriguez D.X., Kim A.J. Receptivity and the Welcoming Cities movement: Advancing a regional immigrant integration policy framework in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia. Papers in Applied Geography. 2017;3(3–4):355–379. doi: 10.1080/23754931.2017.1367957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel P.N., Rodriguez D.X., Krumroy J. From municipal to regional immigrant integration in a major emerging gateway: Creating a community to plan a Welcoming Metro Atlanta. Papers in Applied Geography. 2019;5(1–2):140–165. doi: 10.1080/23754931.2019.1655783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel P.N., Rodriguez D.X., Wang Q. Immigrant integration and receptivity policy formation in Welcoming Cities. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2019;48(1):1142–1166. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2019.1572456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K.R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey B.N. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am. J. Public Health. 2018;108(4):460–463. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Immigration as A Social Determinant of Health: Proceedings of A Workshop. 2018. Paper presented at the Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Immigration Law Center. (2020). Understanding the impact of key provisions of COVID-19 relief bills on immigrant communities. Retrieved from https://www.nilc.org/issues/economic-support/impact-of-covid19-relief-bills-on-immigrant-communities/.

- Page K.R., Venkataramani M., Beyrer C., Polk S. Undocumented U.S. immigrants and COVID-19. N.Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmet W.E., Sainsbury-Wong L., Prabhu M. Immigration and health: law, policy, and ethics. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2017;45:55–59. doi: 10.1177/1073110517703326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patler C., Laster Pirtle W. From undocumented to lawfully present: do changes to legal status impact psychological wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults? Soc. Sci. Med. 2017;199:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramji-Nogales J., Goldner Lang I. Freedom of movement, migration, and borders. J. Hum. Rights. 2020;19(5):593–602. doi: 10.1080/14754835.2020.1830045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J.D., Tehrani S.O. Environments, behaviors, and inequalities: reflecting on the impacts of the influenza and coronavirus pandemics in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(12):4484. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D.X., Hill J., McDaniel P.N. A scoping review of literature about mental health and well-being among immigrant communities in the United States. Health Promotion Practice. 2021;22(2):181–192. doi: 10.1177/1524839920942511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D.X., McDaniel P.N., Bisio G. ‘FU’: One response to the liminal state immigrant youth must navigate. Law & Policy. 2019;41(1):59–79. doi: 10.1111/lapo.12117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D.X., Rodriguez S.C., Zehyoue B.C.V. A content analysis of the contributions in the narratives of DACA youth. Journal of Youth Development. 2019;14(2):64–78. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2019.682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rollston R., Galea S. COVID-19 and the social determinants of health. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020;34(6):687–689. doi: 10.1177/0890117120930536b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch J.C., de Hernandez B.U., Williams L., Smith H.A., Sorensen J., Furuseth O.J., Dulin M.F. Por nuestros ojos: understanding social determinants of health through the eyes of youth. Progr. Commun. Health Partnerships: Res. Educ. Action. 2014;8(2):197–205. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, K., & Tolbert, J. (2020). Limitations of the program for uninsured COVID-19 patients raise concerns. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/limitations-of-the-program-for-uninsured-covid-19-patients-raise-concerns/.

- Shor E., Roelfs D., Vang Z.M. The “Hispanic mortality paradox” revisited: meta-analysis and meta-regression of life-course differentials in Latin American and Caribbean immigrants’ mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017;186:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemons R., Raymond-Flesch M., Auerswald C., Brindis C. Coming of age on the margins: mental health and wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2017;19(3):543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpson J.P., Wilson F.A. Medicaid expansion improved health insurance coverage for immigrants, but disparities persist. Health Aff. 2018;37(10):1656–1662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpson J.P., Wilson F.A., Murillo R., Pagan J.A. Persistent disparities in cholesterol screening among immigrants to the United States. Int. J. Equity Health. 2012;11(1):22–25. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am. Psychol. 1992;47(1):6–22. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.6. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996;10(4):282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhinaraset M., To T.M., Ling I., Melo J., Chavarin J. The influence of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals on undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander young adults: through a social determinants of health lens. J. Adolesc. Health. 2017;60(6):741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The COVID Tracking Project, 2020. The COVID racial data tracker. Retrieved from https://covidtracking.com/race.

- United States Census Bureau. (2020a). Table 1.1 population by sex, age, nativity, and U.S. citizenship status: 2019. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/foreign-born/cps-2019.html.

- United States Census Bureau. (2020b). Table 3.1. Foreign-born population by sex, age, and world region of birth: 2019 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/foreign-born/cps-2019.html.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2020). Public charge. Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/public-charge.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). Social determinants of health. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health.

- Unites States Department of Homeland Security. (2020). Fact sheet: DHS measures on the border to limit the further spread of coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/10/19/fact-sheet-dhs-measures-border-limit-further-spread-coronavirus.

- United States Department of Homeland Security. (2018). Definition of terms. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/data-standards-and-definitions/definition-terms.

- United States Department of State. (2021). Presidential proclamations on novel coronavirus. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/News/visas-news/presidential-proclamation-coronavirus.html.

- United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (2020). Updated ICE statement on COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/updated-ice-statement-covid-19.

- van Dorn A., Cooney R.E., Sabin M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the U.S. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E.D., Sanchez G.R., Juárez M.D. The impact of punitive immigrant laws on the health of Latina/o populations. Polit. Policy. 2017;45(3):312–337. doi: 10.1111/polp.12203. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E., Ybarra V. U.S. citizen children of undocumented parents: the link between state immigration policy and the health of Latino children. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2017;19(4):913–920. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0463-6. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramani A.S., Shah S.J., O'Brien R., Kawachi I., Tsai A.C. Health consequences of the U.S. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration programme: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e175–e181. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viladrich A. Beyond welfare reform: reframing undocumented immigrants’ entitlement to health care in the United States, a critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(6):822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Purdie-Vaughns V. Needed interventions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in health. J. Health Polit. 2016;41(4):627–651. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3620857. Policy and Law Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.T. COVID-19 and health equity: it's deeper than preexisting conditions Public Health Newswire. Am. Public Health Assoc. 2020 http://www.publichealthnewswire.org/?p=covid-19-and-equity-1 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson F.A., Stimpson J.P. US policies increase vulnerability of immigrant communities to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Glob. Health. 2020;86(1):57. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2897. https://www.annalsofglobalhealth.org/articles/10.5334/aogh.2897/ Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. About social determinants of health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/.

- Yeo Y. Healthcare inequality issues among immigrant elders after neoliberal welfare reform: empirical findings from the United States. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017;18(5):547–565. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0809-y. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]