SUMMARY

Background

Pentraxin-2 (PTX-2), a serum protein, inhibits inflammation and fibrosis, and recombinant PTX-2 is being tested as an anti-fibrotic agent.

Aim

To evaluate the association between serum PTX-2 levels and fibrosis stage in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Methods

Serum pentraxin-2 levels were compared between four groups of well-characterised patients including NAFLD with no fibrosis, NAFLD with mild-moderate fibrosis (stage 1–2), NAFLD with advanced fibrosis (stage 3–4), and age-sex matched non-NAFLD controls.

Results

Sixty subjects were included in the study. The mean age was 58.9 years, 68% were male and 58% were Caucasian. In univariate analysis, serum PTX-2 levels significantly decreased from non-NAFLD controls to mild NAFLD with no fibrosis, to NAFLD with mild-moderate fibrosis and were lowest in patients with NAFLD and advanced fibrosis, in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.0001). In multivariable-adjusted analyses controlling for age, sex, albumin, and CRP, the results remained consistent and statistically significant. Serum PTX-2 level had an AUROC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.71–0.97) for the diagnosis of NAFLD, and an AUROC of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.65–0.90) for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD. Serum PTX-2 levels also decreased with increasing liver stiffness as estimated by magnetic resonance elastography (r = −0.31, P = 0.02).

Conclusions

PTX-2 levels are significantly lower in patients with NAFLD compared to non-NAFLD controls, and decline further in patients with advanced fibrosis. PTX-2 may therefore be both a biomarker of disease and a potential target for anti-fibrotic therapy with the recombinant pentraxin-2.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the United States, yet effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies are notably lacking.1 The absence of accurate noninvasive markers to differentiate simple steatosis from more clinically significant forms of NAFLD including non-alcohol steatohepatitis (NASH),2 and the limited availability of techniques such as ultrasound elastography to identify patients with NAFLD-related fibrosis, render the development of novel diagnostic and treatment strategies urgent.

Pentraxins are a family of highly conserved serum proteins with diverse functions in innate immunity, as acute phase reactants, and in the regulation of responses to cellular damage and fibrotic remodelling. Pentraxin-2 (PTX-2) has been shown to modify neutrophil adhesion,3, 4 inhibit fibrocyte differentiation,4–8 and enhance phagocytosis of cell debris by phagocytes and macrophages.4, 9, 10 Thus, PTX-2 plays an important role in inhibiting multiple aspects of the regulation of fibrogenesis and wound healing.11 Serum PTX-2 levels also correlate inversely with lung function in models of pulmonary fibrosis,12, 13 and maintenance of PTX-2 levels at a site of inflammation and injury may prevent fibrosis formation and progression.

Administration of exogenous PTX-2 has thus been tested in animal models in several forms of chronic fibrotic disease, including carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and bile duct ligation-induced liver fibrosis, leading to diminished fibrosis progression.14 Recombinant PTX −2 is also now being administered in human clinical trials for the prevention and treatment of chronic fibrotic diseases. In the first report of recombinant PTX-2 (PRM-151) in healthy volunteers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis, baseline PTX-2 levels were lower in those patients with pulmonary fibrosis compared with controls, and PTX-2 infusion resulted in a decrease in the percentage of circulating fibrocytes.13 As a result, larger clinical trials are now ongoing in patients with pulmonary fibrosis, as well as myelofibrosis and for the prevention of scarring following trabeculectomy for glaucoma.15

PTX-2 may therefore be both a biomarker of a profibrotic response to tissue injury, as well as a therapeutic target for fibrotic disease states. We aimed for the first time to evaluate the association between serum PTX-2 levels and fibrosis stage in patients with NAFLD. We hypothesised that serum PTX-2 levels would be inversely associated with hepatic fibrosis as replacement of serum PTX-2 is considered a potential and novel anti-fibrotic strategy for the treatment of hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting, study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional analysis of uniquely well-characterised adult patients with NAFLD enrolled in a previously reported prospective cohort.15, 16 Patients in this cohort underwent a standardised clinical research visit including history, physical exam, biochemical phenotyping, liver biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging-estimated proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) for fat quantification and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) to measure liver stiffness. Patients with NAFLD were selected, matched for age and gender, from three well-characterised groups: NAFLD with no fibrosis (stage 0), NAFLD with mild-moderate fibrosis (stage 1–2) and NAFLD with advanced fibrosis (stage 3–4). In addition, non-NAFLD controls were also evaluated, again matched for age and gender. All subjects in this study were recruited from the UCSD NAFLD Translational Research Unit and signed informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

NAFLD patient cohort.

All patients with NAFLD in this study had liver biopsy-proven disease and an MRI-PDFF fat fraction ≥5%. Inclusion Criteria for the NAFLD cohort included (i) age at least 18 years, (ii) ability and willingness to give written, informed consent and (iii) minimal or no alcohol use history consistent with NAFLD. Exclusion Criteria included (i) clinical or histological evidence of alcoholic liver disease, (ii) regular and excessive use of alcohol within the 2 years prior to interview defined as alcohol intake greater than 14 drinks per week in a man or greater than 7 drinks per week in a woman, or (iii) secondary causes of hepatic steatosis including previous surgeries, bariatric surgery, total parenteral nutrition, short bowel syndrome, steatogenic medications, evidence of chronic hepatitis B as marked by the presence of HBsAg in serum, evidence of chronic hepatitis C as marked by the presence of anti-HCV or HCV RNA in serum, evidence of other causes of liver disease, such as alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, glycogen storage disease, dysbetalipoproteinemia, haemochromatosis, autoimmune liver disease, or drug-induced liver injury or concomitant severe underlying systemic illness that in the opinion of the investigator would interfere with the study.

Non-NAFLD healthy controls.

Non-NAFLD healthy controls with no clinical or biochemical evidence of liver disease and <5% fat fraction by MRI-PDFF were selected from a second prospective cohort of patients with NAFLD and their unaffected family members (NCT01643512).

Inclusion criteria in the non-NAFLD control group included (i) age greater than 18 years; (ii) liver MRI-PDFF <5% and (iii) no history of known liver disease. Exclusion criteria included (i) age less than 18 years; (ii) significant systemic illness; (iii) inability to undergo MRI and (iv) evidence of possible liver disease, including any previous liver biopsy, positive hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C viral RNA, or autoimmune serologies, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, haemochromatosis genetic testing or low ceruloplasmin.

Histological assessment

All patients with NAFLD underwent liver biopsy, which was evaluated by an experienced liver pathologist blinded to clinical, radiology and biomarker data. All biopsies were scored using the NASH clinical research network histological scoring system,16 including fibrosis stage (range 0–4). NAFLD patients were classified as having NAFLD with no fibrosis (stage 0), NAFLD with mild-moderate fibrosis (stage 1–2) and NAFLD with advanced fibrosis (bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, stage 3–4). In addition, the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS), and its component measures including the severity of steatosis (range 0–3), inflammation (range 0–3) and hepatocyte ballooning (range 0–2) were evaluated.

Magnetic resonance imaging and elastography assessment

MRI-PDFF fat quantification was available for all patients. As liver biopsy is unethical in normal individuals and other non-invasive measures such as ultrasound and computed tomography lack sufficient sensitivity to exclude steatosis, especially at liver fat fraction between 1% and 10%, MRI-PDFF was utilised for fat quantification and for the exclusion of steatosis in the non-NAFLD control group. MRI-PDFF is highly accurate, sensitive, reproducible and precise in the identification of hepatic steatosis.17, 18 A detailed description of the MRI-PDFF protocol has been previously published.17–23

MRE-derived liver stiffness was also measured for all patients. Previous studies have shown that MRE is an accurate and robust, non-invasive, quantitative imaging biomarker for hepatic fibrosis.23–25 MRE exams were performed with patients in the supine position, with a 19-cm diameter acoustic pressure-activated passive driver placed over the right anterior chest wall with its center level with xiphoid process. Two-dimensional (2D) gradient echo MRE acquisitions were performed with parameters as previously described.23, 24, 26–29 The data were processed to generate images depicting the complex shear stiffness of liver tissue, using direct inversion.26, 27 The elastograms were transferred offline for analysis with a trained image analyst who manually drew regions of interest (ROIs) on the elastograms. ROIs were drawn at each of the four slice locations in portions of the liver in which the corresponding wave images showed clearly observable wave propagation. The mean liver stiffness was calculated by averaging the per-pixel stiffness values across the ROIs at the four slice locations.

All MRI-PDFF and MRE measurements were made in the analyses of the original patients cohorts, blinded to histological and clinical data, and prior to PTX-2 measurement.

Pentraxin-2 measurement

A fasting serum sample was collected in the morning of the clinical research visit and stored in a −80 °C freezer. The median (IQR) time between blood sample collection and liver biopsy was 35 (86) days and between blood and MRE exam as 11 (35.5) days. Serum PTX-2 and C-reactive protein (CRP, another member of the Pentraxin protein family) levels were assayed by ELISA (Ray Biotech, Norcross, GA, USA). All samples were run in triplicate, blinded to the group assignment and clinical status of the patient. All blood tests were performed on blood sampled from a single day.

Statistical analysis and sample-size estimation

Baseline characteristics and biomarker levels were compared across the four groups by ANOVA or Fischer’s exact test as appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed for PTX-2 as a classifier of advanced fibrosis, as well as of NAFLD as compared to non-NAFLD controls. The measure of overall performance was the area under the ROC (AU-ROC). PTX-2 levels were also correlated with liver stiffness by two-dimensional MRE.

Power analysis indicated a 81% chance of detecting an effect size of a 1.2 standard deviation difference overall between the highest and lowest group means as significant at an alpha of 0.05 (two-tailed) with a total of 60 patients distributed equally between the four groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

A total of 60 patients are included in this study, 15 in each of four groups: non-NAFLD controls, NAFLD with no fibrosis, NAFLD with mild-moderate fibrosis, and NAFLD with advanced fibrosis. Demographical characteristics were similar between groups, including mean age, race and ethnicity (Table 1). Patients with NAFLD and moderate or advanced fibrosis were more likely to have diabetes mellitus, and had higher glucose levels, haemoglobin A1c and body mass index (BMI) compared to those with mild NAFLD or normal controls. In addition, patients with NAFLD had statistically significant elevations in aminotransferases compared to non-NAFLD controls, and those with advanced fibrosis had significantly lower platelets than patients in other groups. CRP levels did not differ between groups.

Table 1 |.

Patient characteristics and Pentraxin-2 levels by patient group

| Characteristic | Normal (n = 15) | Mild NAFL (n = 15) | Moderate fibrosis (n = 15) | Advanced fibrosis (n = 15) | P* | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 59.2 (5.7) | 58.9 (5.2) | 56.5 (5.6) | 61.1 (4.4) | 0.1468 | 0.5944 |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (80.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 11 (73.3%) | 10 (66.7%) | 0.5195 | 0.7096 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 13 (86.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 9 (60.0%) | 0.0648 | |

| Black | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 6 (40.0%) | 6 (40.0%) | ||

| Asian | 0 | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0 | ||

| Refused | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | ||

| Anthropometric, mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.6 (5.9) | 28.9 (3.1) | 32.1 (5.8) | 33.4 (4.1) | 0.0003 | <0.0001 |

| Clinical, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 3 (20.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0.0020 | 0.0011 |

| Hypertension | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | 13 (86.7%) | 0.0045 | 0.0005 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1 (6.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.2490 | 0.4128 |

| Laboratories, mean (s.d) | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.2) | 4.6 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.3) | 0.1581 | 0.1552 |

| AST (U/L) | 22.3 (6.4) | 36.9 (21.7) | 47.5 (34.7) | 58.2 (25.8) | 0.0014 | <0.0001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.9 (7.0) | 51.0 (35.4) | 73.7 (61.6) | 58.0 (32.2) | 0.0030 | 0.0030 |

| Bilirubin, total (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.3972 | 0.1346 |

| Platelet count (1000/mm3) | 257.3 (47.9) | 252.6 (53.9) | 246.9 (49.4) | 182.1 (56.4) | 0.0007 | 0.0004 |

| International normalised ratio | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.0019 | 0.0009 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dL) | 92.7 (10.0) | 101.3 (15.4) | 112.4 (24.1) | 116.1 (36.3) | 0.0362 | 0.0044 |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.8 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.3) | 6.2 (0.7) | 6.4 (0.6) | 0.0041 | 0.0004 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 102.4 (69.0) | 151.1 (72.2) | 156.0 (68.9) | 179.5 (184.2) | 0.2858 | 0.0687 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 66.8 (16.5) | 56.4 (14.8) | 50.9 (13.5) | 45.4 (12.8) | 0.0013 | 0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 108.5 (34.6) | 120.1 (36.3) | 101.5 (39.8) | 93.3 (31.8) | 0.2353 | 0.1330 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1839.9 (3030.8) | 2294.7 (3493.3) | 4002.6 (4870.4) | 3874.9 (2717.2) | 0.2593 | 0.0670 |

| Pentraxin-2 (μg/mL), mean (95% CI) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 80.2 (63.7–96.7) | 23.7 (7.2–40.2) | 22.0 (5.5–38.6) | 12.2 (4.3–28.7) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Age, gender adjusted | 85.2 (68.0–102.5) | 24.2 (7.9–40.6) | 25.3 (8.1–42.5) | 15.4 (1.6–32.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Age, gender, albumin adjusted | 85.2 (67.8–102.6) | 24.1 (7.6–40.6) | 25.3 (8.0–42.7) | 16.0 (1.5–33.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Age, gender, CRP adjusted | 86.5 (68.9–104.2) | 24.9 (8.4–41.4) | 24.5 (7.1–41.9) | 14.9 (−2.3–32.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Continuous variables were analysed with ANOVA, categorical variables were analysed with Fisher’s exact test. The P values in bold are statistically significant.

Test of linear trend.

Association between serum PTX-2 levels and stage of fibrosis.

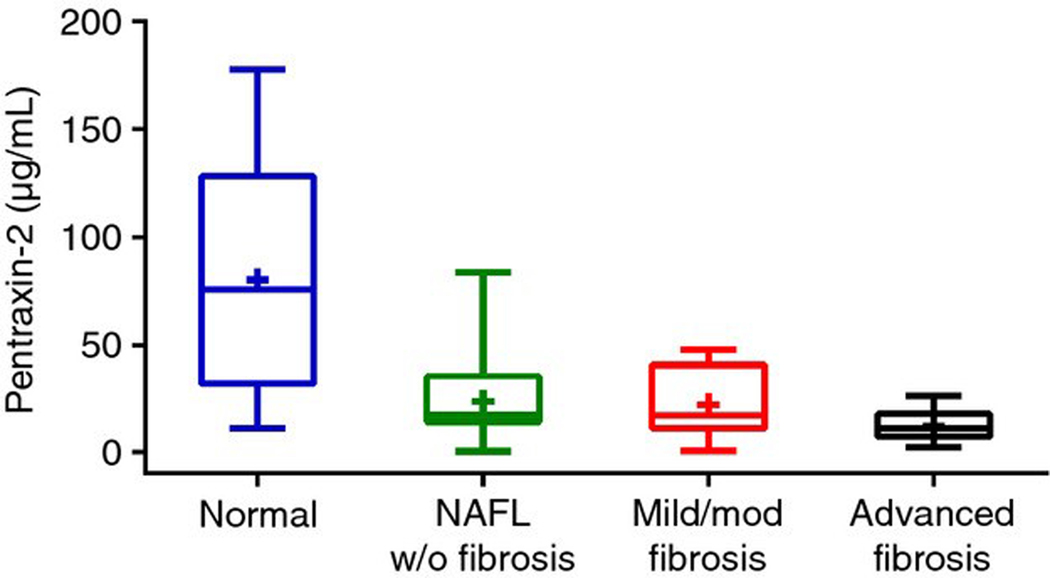

Mean (95% confidence interval) PTX-2 levels were significantly lower in patients with advanced fibrosis [12.2 (−4.3–28.7) μg/mL] compared to those with mild-moderate fibrosis [22.0 (5.5–38.6) μg/mL], NAFLD with no fibrosis [23.7 (7.2–40.2) μg/mL] and non-NAFLD controls [80.2 (63.7–96.7) μg/mL] (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1 |.

Boxplot of serum PTX-2 levels by patient group. Mean (95% confidence interval) PTX-2 levels were significantly lower in patients with advanced fibrosis [12.2 (−4.3–28.7) μg/mL] compared to those with moderate [22.0 (5.5–38.6) μg/mL] and mild [23.7 (7.2–40.2) μg/mL] NAFLD.

When adjusted in multivariable analysis for age and gender, with or without the addition of either albumin or CRP, these relationships were similar and remained significant with P < 0.001 (Table 1).

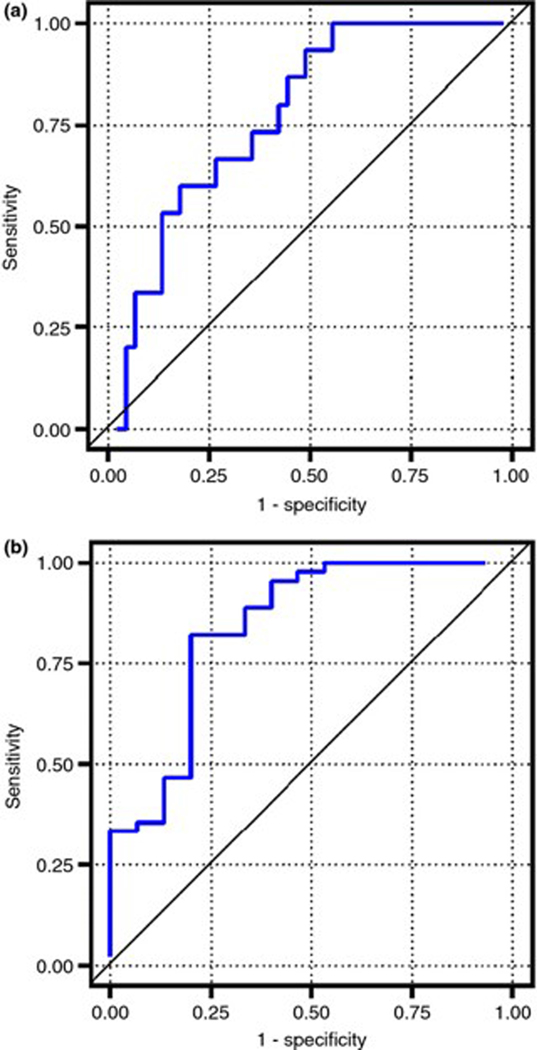

PTX-2 level had an AUROC of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.65–0.90) for the identification of patients with advanced fibrosis (Figure 2a). A PTX −2 level of ≤14.7 μg/mL had a positive and negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis of 44% and 87% respectively.

Figure 2 |.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for PTX-2. (a) PTX-2 level had an AUROC of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.65–0.90) for the identification of patients with advanced fibrosis. (b) PTX-2 had an AUROC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.71–0.97) for the identification of NAFLD compared with normal controls.

Association between serum PTX-2 levels and presence of NAFLD.

Mean (95% confidence interval) serum PTX-2 levels were significantly lower in patients with NAFLD and any stage of fibrosis compared to normal controls [19.3 (14.6–24.0) μg/mL vs. 80.2 (48.0–112.5) μg/mL, P = 0.001].

PTX-2 had an AUROC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.71–0.97) for the identification of NAFLD compared to normal controls (Figure 2b). A PTX −2 level of ≤24 μg/mL had a positive and negative predictive value for NAFLD of 92% and 55% respectively.

ALT was significantly negatively correlated with PTX-2 level (r = −0.33, P = 0.01), while BMI (r = −0.19, P = 0.15), and haemoglobin A1c (r = −0.06, P = 0.67) were not significantly correlated with PTX-2 level.

Association between serum PTX-2 and other histological features of NAFLD.

Biopsy findings for patients in each group are summarised in Table 2. The NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) increased with increasing fibrosis stage, as did lobular inflammation and ballooning. Within fibrosis groups, PTX-2 levels were not impacted by grade of inflammation, ballooning or steatosis.

Table 2 |.

Biopsy and MRE characteristics by patient group

| Normal (n = 15) | Mild NAFL (n = 15) | Moderate fibrosis (n = 15) | Advanced fibrosis (n = 15) | P* | P† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD Activity Score, (NAS) | ||||||

| Mean (s.d.) | – | 3.6 (1.0) | 5.2 (0.9) | 5.5 (1.2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | – | 2 (13.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0.0059 | |

| 3 | – | 5 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | – | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | ||

| 5 | – | 3 (20.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | ||

| 6 | – | 0 | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | ||

| 7 | – | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | ||

| Lobular inflammation (score), (no. foci per 200 × field), n (%) | ||||||

| None (0) | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0004 | |

| <2 foci (1) | – | 10 (66.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | ||

| 2–4 foci (2) | – | 5 (33.3%) | 14 (93.3%) | 10 (71.4%) | ||

| >4 foci (3) | – | 0 | 0 | 2 (14.3%) | ||

| Steatosis | ||||||

| Grade, n (%) | ||||||

| <5% (0) | – | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 0.2244 | |

| 5–33% (1) | – | 9 (60.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 6 (40.0%) | ||

| 33–66% (2) | – | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | ||

| >66% (3) | – | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | ||

| Ballooning (score), n (%) | ||||||

| None (0) | – | 6 (40.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 0.0010 | |

| Few (1) | – | 7 (46.7%) | 9 (60.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | ||

| Many (2) | – | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 11 (78.6%) | ||

| MRE, mean (s.d.) | 2.2 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.3) | 5.6 (1.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Continuous variables were analysed with ANOVA, categorical variables were analysed with Fisher’s exact test. The P values in bold are statistically significant.

Test of linear trend.

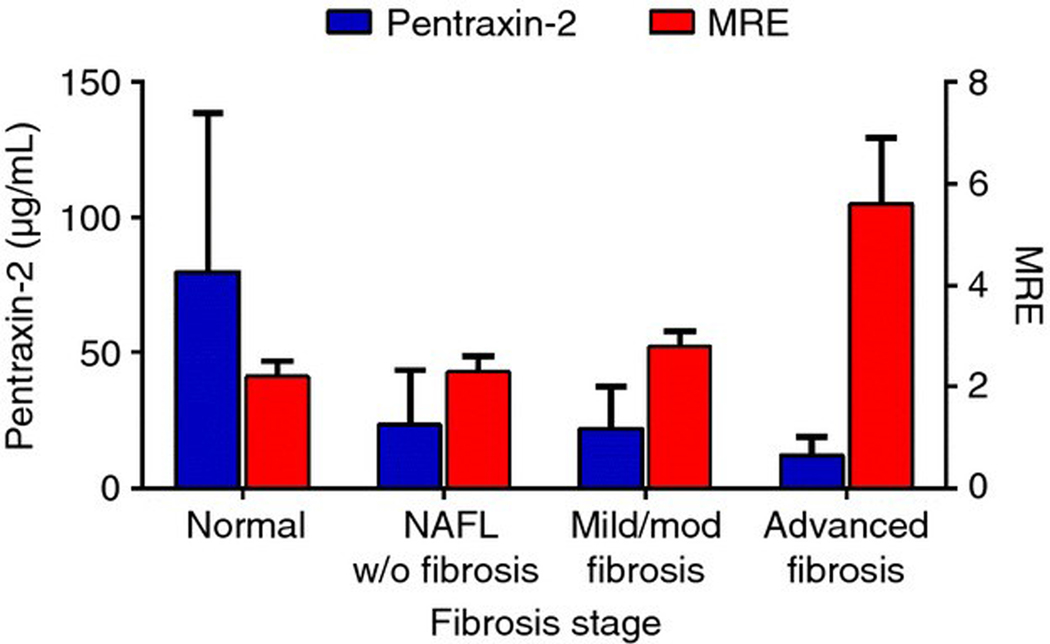

Correlation between serum PTX-2 and MRE.

Mean MRE stiffness values significantly increased with increasing fibrosis stage (Table 2), and PTX −2 levels were significantly negatively correlated with MRE values (r = −0.31, P = 0.02, Figure 3).

Figure 3 |.

Bar graph demonstrating the negative correlation between PTX-2 and MRE liver stiffness.

DISCUSSION

In this pilot proof of concept study, we report the first measurements of serum PTX-2 levels in patients with chronic liver disease. In this cohort of uniquely well-characterised NAFLD patients, PTX-2 levels were significantly lower in patients with NAFLD and advanced fibrosis compared to patients with early stage disease. Levels below 14.7 μg/mL were strongly predictive of advanced fibrosis. In addition, PTX-2 levels were inversely correlated with increasing fibrosis stage and with MRE liver stiffness values throughout the spectrum of NAFLD-related fibrosis. This decrease in PTX-2 levels is similar to those seen in pulmonary fibrosis patients,13 and is unlikely to be due to a generalised decrease in hepatic synthetic capacity given the similar albumin and CRP levels between groups.

Interestingly, PTX-2 levels were also significantly decreased in patients with NAFLD and no fibrosis compared to healthy controls. PTX-2 < 24 μg/mL had a 92% positive predictive value for the diagnosis of NAFLD. Pentraxin-3, a long pentraxin and acute phase reactant that is expressed locally in the setting of an inflammatory stimulus, including in adipose tissues and atherosclerotic lesions, has previously been implicated in obesity and cardiovascular disease.30–38 However, PTX-2 is predominantly synthesised in the liver,39 and there are no previously published data on PTX-2 levels in these populations. In this cohort, PTX-2 levels were not significantly correlated with BMI or degree of steatosis on liver biopsy, though this cohort may not have had sufficient power to demonstrate these relationships. Thus it is uncertain whether hepatic production of PTX-2 may be inhibited by significant lipid accumulation in the liver. Further mechanistic studies will be required to determine the relationship between hepatic steatosis and PTX-2 production.

As PTX-2 is known to play an important role in the inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation as well as in the regulation of fibrogenesis and wound healing,11, 14 repletion with recombinant protein is a promising therapeutic target. The pre-clinical data on administration of exogenous PTX-2 has shown significant benefit in models of several chronic fibrotic diseases, including bleomycin- or TGF-induced lung fibrosis,12, 40, 41 ischaemia reperfusion injury,7 corneal injury,42 and radiation-induced oral mucositis and fibrosis.43 Importantly, pre-clinical testing in models of chronic liver disease including CCl4- and bile duct ligation-induced liver fibrosis were similarly encouraging.14 When these liver-injured mice were treated with recombinant PTX-2, fibrosis development was significantly inhibited, as was the activation of fibrogenic myofibroblasts, inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α), and pro-fibrogenic genes (e.g. collagen-α1 and α-smooth muscle actin).14

We acknowledge that there is a relatively small sample size in this study, and that our findings need to be confirmed in a multicenter setting in a larger cohort of patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD. In addition, as PTX-2 levels are also decreased in patients with other chronic fibrotic diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis, the utility of PTX-2 as a marker of liver fibrosis specifically in these patients may be limited.

Administration of recombinant PTX-2 has now moved into clinical trials. In the first report of its use in healthy volunteers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis, the infusion was well-tolerated and resulted in a decrease in the percentage of circulating fibrocytes,13 with larger clinical trials now ongoing.15 Given hepatic origin of PTX-2 and the significantly altered levels even in patients with early stage disease, NALFD patients with fibrosis may be an ideal population to study with PTX-2 based interventions.

In summary, this pilot proof of concept study demonstrates that serum PTX-2 levels are significantly lower in patients with NAFLD compared to normal controls, and decline further with advancing fibrosis stage in a dose-dependent manner. This study, along with pre-clinical data on the use of recombinant PTX-2 in animal models of liver fibrosis and safety data from ongoing clinical trials in humans, may provide justification for testing of PTX-2 administration in patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD-related fibrosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: The study sponsor(s) had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, and/or drafting of the manuscript. All authors report that no conflicts of interest exist.

Declaration of funding interests: The study was supported by an investigator initiated study mechanism funded by Promedior Inc. The study was conducted at the Clinical and Translational Research Institute, University of California at San Diego. RL was supported in part by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Foundation – Sucampo – ASP Designated Research Award in Geriatric Gastroenterology and by a T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award; Funding was provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Association of Specialty Professors and the American Gastroenterological Association (grant K23-DK090303).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1592–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedchuk L, Nascimbeni F, Pais R, Charlotte F, Housset C, Ratziu V. Performance and limitations of steatosis biomarkers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 1209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maharjan AS, Roife D, Brazill D, Gomer RH. Serum amyloid P inhibits granulocyte adhesion. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2013; 6: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Distinct Fcgamma receptors mediate the effect of serum amyloid p on neutrophil adhesion and fibrocyte differentiation. J Immunol 2014; 193: 1701–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castano AP, Lin SL, Surowy T, et al. Serum amyloid P inhibits fibrosis through Fc gamma R-dependent monocyte-macrophage regulation in vivo. Sci Transl Med 2009; 1: 5ra13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH. FcgammaRI mediates serum amyloid P inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation. J Leukoc Biol 2012; 92: 699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haudek SB, Trial J, Xia Y, Gupta D, Pilling D, Entman ML. Fc receptor engagement mediates differentiation of cardiac fibroblast precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 10179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu J, Marnell LL, Marjon KD, Mold C, Du Clos TW, Sun PD. Structural recognition and functional activation of FcgammaR by innate pentraxins. Nature 2008; 456: 989–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bharadwaj D, Mold C, Markham E, DuClos TW. Serum amyloid P component binds to Fc gamma receptors and opsonizes particles for phagocytosis. J Immunol 2001; 166: 6735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mold C, Gresham HD, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein mediate phagocytosis through murine Fc gamma Rs. J Immunol 2001; 166: 1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naik-Mathuria B, Pilling D, Crawford JR, et al. Serum amyloid P inhibits dermal wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2008; 16: 266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, et al. TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by Serum amyloid P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011; 43: 154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillingh MR, van den Blink B, Moerland M, et al. Recombinant human serum amyloid P in healthy volunteers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013; 26: 672–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cong M, Jiang C, Taura K, et al. Serum Amyloid P Attenuates Hepatic Fibrosis in Mice by Inhibiting the Activation of Fibrocytes and Hepatic Stellate Cells. Hepatology 2011; 54(4 Suppl.): 736A.21626528 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Available at: www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed 8 March 2015).

- 16.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41: 1313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noureddin M, Lam J, Peterson MR, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging versus histology for quantifying changes in liver fat in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease trials. Hepatology 2013; 58: 1930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le TA, Chen J, Changchien C, et al. Effect of colesevelam on liver fat quantified by magnetic resonance in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 2012; 56: 922–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Permutt Z, Le TA, Peterson MR, et al. Correlation between liver histology and novel magnetic resonance imaging in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - MRI accurately quantifies hepatic steatosis in NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36: 22–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang A, Tan J, Sun M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: MR imaging of liver proton density fat fraction to assess hepatic steatosis. Radiology 2013; 267: 422–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel NS, Doycheva I, Peterson MR, et al. Effect of weight loss on MRI estimation of liver fat and volume in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 561–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel NS, Peterson MR, Brenner DA, Heba E, Sirlin C, Loomba R. Association between novel MRI-estimated pancreatic fat and liver histology-determined steatosis and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 630–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loomba R, Wolfson T, Ang B, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography predicts advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology 2014; 60: 1920–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Kim WR, Talwalkar JA, Kim HJ, Ehman RL. Advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: noninvasive assessment with MR elastography. Radiology 2013; 268: 411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui J, Ang B, Haufe W, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance elastography vs. eight clinical prediction rules for noninvasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 1271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Talwalkar JA, Yin M, Glaser KJ, Sanderson SO, Ehman RL. Early detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by using MR elastography. Radiology 2011; 259: 749–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin M, Talwalkar JA, Glaser KJ, et al. Assessment of hepatic fibrosis with magnetic resonance elastography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5: 1207–13 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xanthakos SA, Podberesky DJ, Serai SD, et al. Use of magnetic resonance elastography to assess hepatic fibrosis in children with chronic liver disease. J Pediatr 2014; 164: 186–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkatesh SK, Yin M, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography of liver: technique, analysis, and clinical applications. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37: 544–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alberti L, Gilardini L, Zulian A, et al. Expression of long pentraxin PTX3 in human adipose tissue and its relation with cardiovascular risk factors. Atherosclerosis 2009; 202: 455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barazzoni R, Aleksova A, Carriere C, et al. Obesity and high waist circumference are associated with low circulating pentraxin-3 in acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2013; 12: 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witasp A, Ryden M, Carrero JJ, et al. Elevated circulating levels and tissue expression of pentraxin 3 in uremia: a reflection of endothelial dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e63493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyaki A, Choi Y, Maeda S. Pentraxin 3 production in the adipose tissue and the skeletal muscle in diabetic-obese mice. Am J Med Sci 2014; 347: 228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto T, Rashid Qureshi A, Heimburger O, et al. Inverse relationship between the inflammatory marker pentraxin-3, fat body mass, and abdominal obesity in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 2785–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osorio-Conles O, Guitart M, Chacon MR, et al. Plasma PTX3 protein levels inversely correlate with insulin secretion and obesity, whereas visceral adipose tissue PTX3 gene expression is increased in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011; 301: E1254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abderrahim-Ferkoune A, Bezy O, Chiellini C, et al. Characterization of the long pentraxin PTX3 as a TNFalpha-induced secreted protein of adipose cells. J Lipid Res 2003; 44: 994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyaki A, Maeda S, Choi Y, Akazawa N, Eto M, Tanaka K, et al. Association of plasma pentraxin 3 with arterial stiffness in overweight and obese individuals. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26: 1250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J, Gozal D, Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L. TREM-1 and pentraxin-3 plasma levels and their association with obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and endothelial function in children. Sleep 2013; 36: 923–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Clos TW. Pentraxins: structure, function, and role in inflammation. ISRN Inflamm 2013; 2013: 379040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pilling D, Roife D, Wang M, et al. Reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by serum amyloid P. J Immunol 2007; 179: 4035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murray LA, Rosada R, Moreira AP, et al. Serum amyloid P therapeutically attenuates murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via its effects on macrophages. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e9683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santhiago MR, Singh V, Barbosa FL, Agrawal V, Wilson SE. Monocyte development inhibitor PRM-151 decreases corneal myofibroblast generation in rabbits. Exp Eye Res 2011; 93: 786–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray LA, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, et al. Serum amyloid P ameliorates radiation-induced oral mucositis and fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2010; 3: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]