Summary

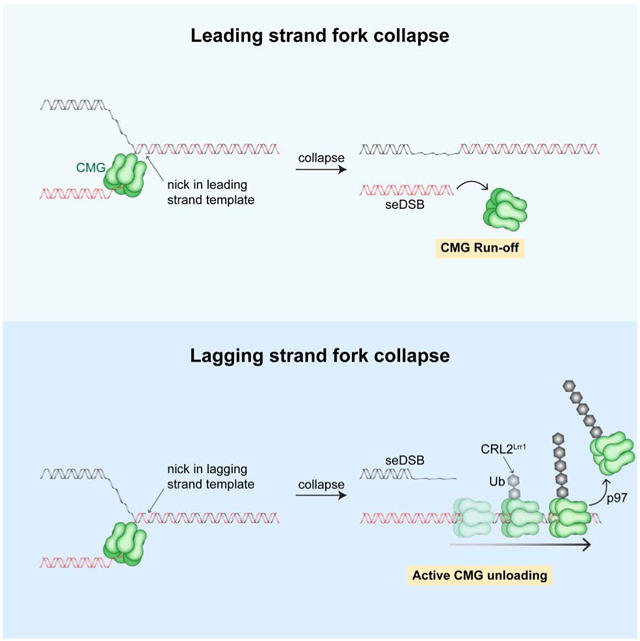

DNA damage impedes replication fork progression and threatens genome stability. Upon encounter with most DNA adducts, the replicative CMG helicase (CDC45-MCM2-7-GINS) stalls or uncouples from the point of synthesis, yet eventually resumes replication. However, little is known about the effect on replication of single-strand breaks or "nicks", which are abundant in mammalian cells. Using Xenopus egg extracts, we reveal that CMG collision with a nick in the leading strand template generates a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB). Moreover, CMG, which encircles the leading strand template, “runs off” the end of the DSB. In contrast, CMG collision with a lagging strand nick generates a broken end with a single-stranded overhang. In this setting, CMG translocates along double-stranded DNA beyond the break and is then ubiquitylated and removed from chromatin by the same pathway used during replication termination. Our results show that nicks are uniquely dangerous DNA lesions that invariably cause replisome disassembly, and they argue that CMG cannot be stored on dsDNA while cells resolve replication stress.

Keywords: DNA replication, DNA repair, single molecule, fork collapse, double-strand break, single-strand break, CMG, homologous recombination

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Vrtis et al. show that when a replisome encounters a single-strand DNA break in the leading or lagging strand template, the replication fork collapses, generating a double-strand break. Collapse is accompanied by loss of the replicative helicase from DNA, implying that fork restart would require recruitment of a new helicase.

Introduction

Single-stranded DNA breaks or “nicks” are generated by ionizing radiation, free radicals, topoisomerase I, and as intermediates in base excision repair (BER) (Caldecott, 2008). Nicks encountered in the leading strand template during eukaryotic replication cause replication fork "collapse" with formation of a single-ended double-strand break (seDSB; Figure S1A,i) (Nielsen et al., 2009; Strumberg et al., 2000), but whether this also occurs at lagging strand nicks has not been examined (Figure S1A,ii). seDSBs can be repaired by a subpathway of homologous recombination (HR) known as break-induced replication (BIR), which involves resection of the broken end, invasion into the sister chromatid, and replication to the end of the chromosome or until a converging fork is encountered (Haber, 1999; Mayle et al., 2015). Loss of the recombination proteins RAD51, BRCA1, or BRCA2 is lethal in unperturbed vertebrate cells (Hakem et al., 1996; Sharan et al., 1997; Sonoda et al., 1998; Tsuzuki et al., 1996), consistent with estimates that ~50 replication forks normally collapse in every S phase (Vilenchik and Knudson, 2003). Moreover, cancer therapeutics such as topoisomerase and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors function by stabilizing nicks and promoting replication fork collapse (Hengel et al., 2017). Thus, the repair of collapsed forks is essential for cell viability and represents a prominent target in cancer therapy.

A central question is whether the replicative helicase CMG participates in replication restart after fork collapse. Early work suggested that CMG participates in BIR and that it remains on chromatin during fork collapse (Hashimoto et al., 2012; Lydeard et al., 2010). Moreover, a recent single molecule study suggested that when replication forks encounter DNA damage, CMG moves onto parental DNA beyond the damage, and when repair is complete, it re-engages with the fork for replication restart (Wasserman et al., 2019). However, other studies conclude that CMG is not involved in BIR (Dilley et al., 2016; Natsume et al., 2017; Sonneville et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2013). To determine whether CMG could function in replication restart, tracking its fate during replication stress in a physiological setting is crucial. Another key factor dictating repair is the DNA structure generated during fork collapse. The specific structure formed may depend on whether collapse occurs at a nick in the leading strand template (Figure S1A,i, “Lead Collapse”) or lagging strand template (Figure S1A,ii, “Lag Collapse”). Work in human cells suggests that during lead collapse, a blunt, seDSB is generated (Strumberg et al., 2000) (Figure S1A,i) that would have to undergo resection prior to strand invasion. However, the lag collapse fork structure is unknown. In summary, whether the replisome is recycled for BIR and which DNA structures and processing steps underlie this clinically relevant DNA repair pathway remain unclear.

Here, we use ensemble and single molecule approaches in Xenopus egg extracts to examine the fate of the replication fork after collision with strand-specific nicks. Strikingly, after both lead and lag collapse, the CMG helicase is lost from the DNA, but via distinct mechanisms. Further, analysis of the fork DNA structures generated shows that lag collapse is more amenable to repair than lead collapse.

Results

Lead collapse generates a nearly blunt seDSB and a gap in the lagging strand

We wanted to study DNA replication fork collapse at a site-specific nick using Xenopus egg extracts, which support sequence non-specific replication initiation on added DNA, followed by a complete round of replication (Figure S1B) (Walter et al., 1998). However, nicked plasmid added to egg extract was rapidly ligated (Figure S1C, lanes 1-6) before forks would be able to reach the nick. Chemical modification of nucleotides flanking the nick did not prevent ligation (data not shown). We therefore flanked the nick with Tet operator (tetO) sites to which we bound the Tet repressor (TetR) before adding the plasmid to extract. We reasoned that TetR might stabilize the nick by blocking access to DNA ligase. Indeed, although TetR did not block fork progression (see Figure 3C legend below), it increased the half-life of the nick ~45-fold (Figure S1C). To further increase the probability that forks encounter a nick, we used three consecutive nicks, each flanked by tetO sites (Figure 1A, inset). To compare fork collapse when nicks reside in the leading versus lagging strand templates, it was necessary to ensure that forks arrive at the nicks from only one direction. Therefore, we flanked the nicks on the right with an array of 48 Lac repressors (LacR) (Figure 1A) to prevent arrival of a second fork at the nick (Dewar et al., 2015; Duxin et al., 2014). In this configuration, lead collapse should occur when the rightward fork collides with a nick in the bottom strand (Figure 1A, inset).

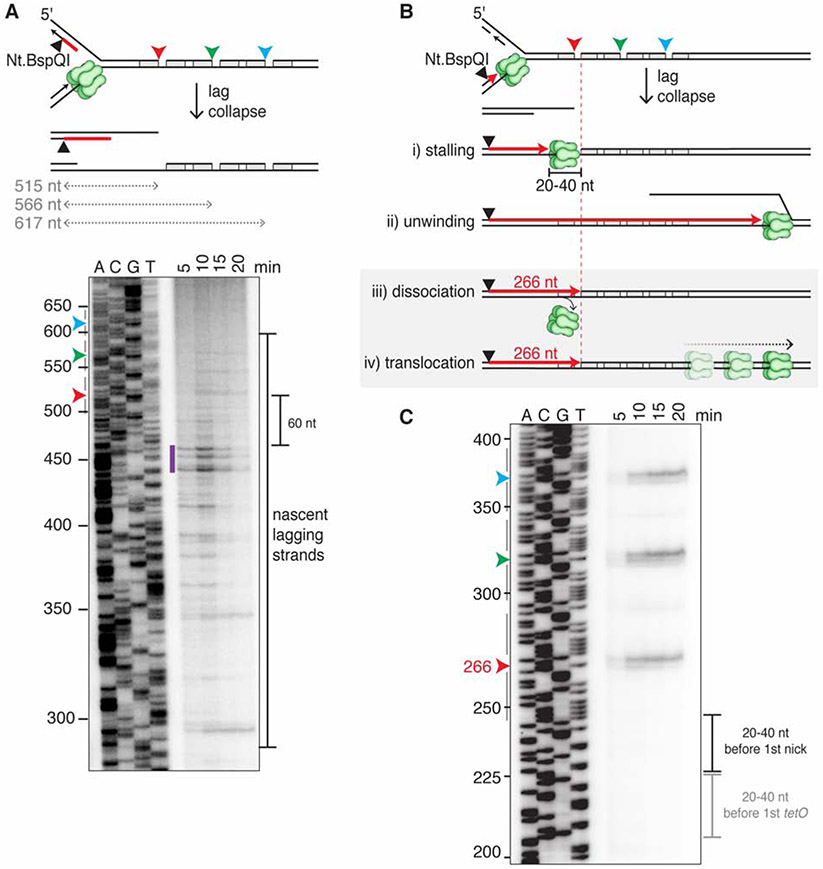

Figure 3. Lag collapse generates a seDSB with a 3’ ssDNA overhang.

(A) Analysis of nascent lagging strands after lag collapse. The Nt.BbvCI-nicked plasmid was replicated in the presence of TetR, LacR, and [a-32P]dATP. After 15 minutes, DNA was extracted and digested with Nt.BspQI to reveal the nascent lagging strands (red line) by denaturing gel electrophoresis. 515 nt, 566 nt, and 617 nt correspond to the distances between the Nt.BspQI site and the three nicks. Arrowheads, location of nicks. Purple bar, most prominent lagging strand products. (B) Four different CMG fates after lagging strand fork collapse, including predicted size of the leading strand. Text for details. (C) As in (A), but with the Nt.BspQI site located on the nascent leading strand. Black bracket, location where leading strands would stall in model (B,i). The lack of signal 20-40 nt before the 1st tetO site (gray bracket) indicates that CMG does not stall at TetR. For both gels, only the relevant portions are shown. Gels are representative images from three biological replicates. See also Figure S3.

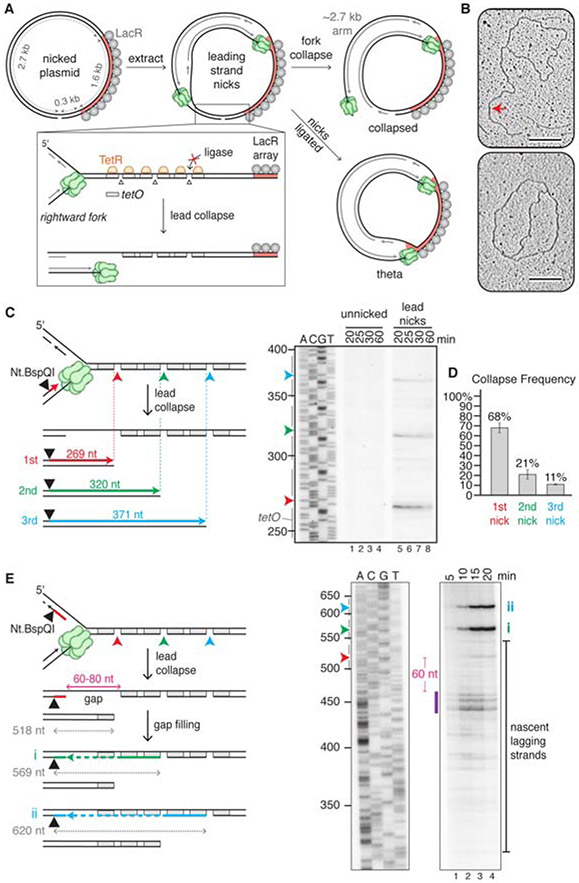

Figure 1. Lead collapse generates a nearly blunt seDSB and a gap in the lagging strand.

(A) Experimental approach used in Figures 1 and 3. (B) Plasmid nicked with Nb.BbvCI was incubated with TetR and LacR and replicated in egg extract for 15 minutes before extracting the DNA for electron microscopy. Collapsed (top) and theta (bottom) structures are shown. Red arrow, 2.7 kb arm. Scale bar, 200 nm. Images are representative from two biological replicates. (C) Analysis of nascent leading strands. Nb.BbvCI-nicked plasmid was replicated as in panel B, but in the presence of [a-32P]dATP. After isolation, DNA was digested with Nt.BspQI, separated via denaturing electrophoresis, and subjected to autoradiography. Only the relevant segment of the gel is shown. Gray bars, tetO sites. (D) Percentage collapse at each of the three nicks in panel C. Error bars, standard deviations from three biological replicates. (E) Repetition of panel C, but with the Nt.BspQI site located on the nascent lagging strand. After fork collapse at the first nick, gap filling from the 3’ end of the nick (still protected by TetR) to the final Okazaki fragment and ligation creates a 569 nt product (i, green line and arrowhead). Collapse at the second nick, gap filling, and ligation generates a 620 nt product (ii, blue line and arrowhead). Purple bar, most prominent lagging strand products. Irrelevant lanes between the two panels shown were removed. Gels are representative images from three biological replicates. See also Figure S1.

When we replicated unnicked plasmid in extracts containing LacR and TetR, a prominent "theta" intermediate was generated (Figure S1D, lanes 1-3), as expected from forks stalling at the outer edges of the LacR array (Duxin et al., 2014). However, in the presence of a nick, a prominent new product appeared that migrated faster than theta (Figure S1D, lanes 4-6, red arrowhead). To identify the structure of this new product, we cut out the band, extracted the DNA, and performed transmission electron microscopy. This analysis revealed that the new product corresponds to a sigma-shaped, "collapsed" structure in which a linear arm of the expected size (2.7 kb; Figures 1A and S1E) is attached to the circular plasmid (Figure 1B, red arrow). Quantification showed that ~60% of the forks from the nicked plasmid underwent collapse (Figure S1D, lane 4). We attribute the remaining theta products (Figures 1A and 1B, bottom image; Figure S1D) to plasmids in which all three nicks were ligated before fork arrival. Our data provide direct visual confirmation that replication through a leading strand nick causes fork collapse with formation of a seDSB.

To determine the DNA structure of the broken end generated during lead collapse, we labeled nascent DNA stands with [α–32P]dATP and used the single strand endonuclease Nt.BspQI to cleave these strands at a defined position relative to the three TetR-flanked nicks (Figure 1C). Denaturing gel analysis revealed three nascent, ssDNA products whose 3' ends were located close to each of the three nicks (Figure 1C, lanes 5-8). The product associated with collapse at the first nick was most abundant (Figure 1D), as expected from rightward fork movement. Higher resolution mapping showed that leading strand synthesis mostly stopped 3 nt from the end of the break, which should leave a 3 nt, 5' single-stranded DNA overhang (Figure S1F, lanes 5-8). This interpretation is consistent with the properties of purified pol ε, the leading strand polymerase (Hogg et al., 2014). Our results suggest that lead collapse repair should generally require resection of the seDSB.

To map the distribution of nascent lagging strands during lead collapse, we next placed the Nt.BspQI site on the other strand (Figure 1E). Most nascent lagging strands were 440-460 nts in length (Figure 1E; purple bar). Because the first nick is located 518 basepairs from the Nt.BspQI site, we conclude that there is typically a ~60-80 nt gap between the 5' end of the nascent lagging strand and the site of collapse (Figure 1E, “gap”). By 20 minutes, lagging strand fragments declined, indicating gap filling (Figure 1E, lanes 3-4). Consistent with this interpretation, well-defined bands appeared that correspond to gap-filled products that retain the second and third nicks due to TetR (Figure 1E,i,ii). In summary, lead collapse generates a seDSB with a three nucleotide 5' overhang and a lagging strand gap that is subsequently filled in. The data suggest that lead collapse repair involves not only resection but also gap filling.

CMG is lost at the nick after lead collapse

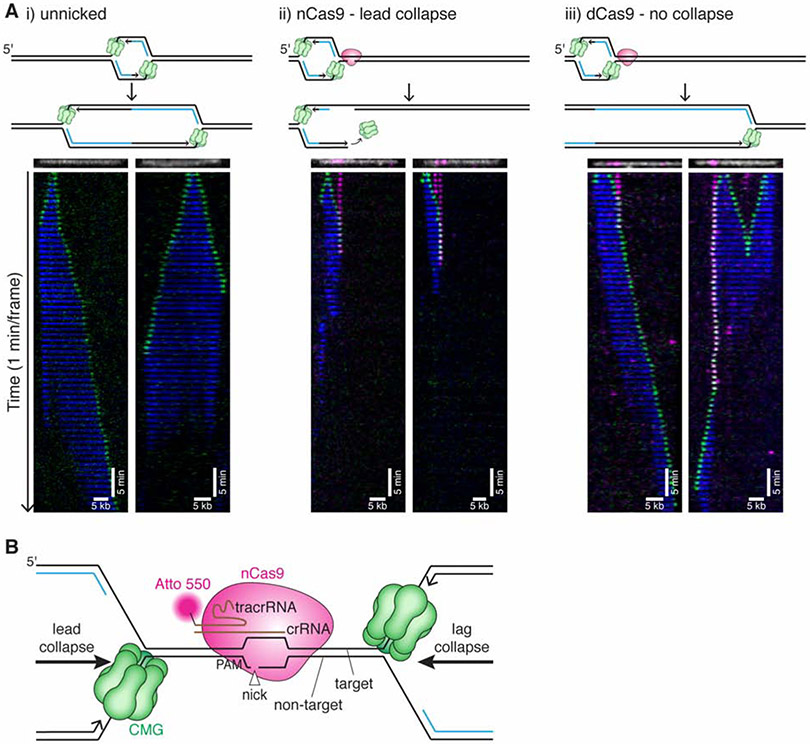

Given that the leading strand is extended to within 3 nucleotides of the break, and because CMG’s DNA footprint comprises 20-40 nt (Fu et al., 2011), our data suggest that CMG loses its association with the DNA end during lead collapse. However, whether CMG dissociates altogether was unclear. To address this question, we used single molecule imaging to visualize CMG dynamics during lead collapse. We replicated stretched, immobilized DNA in GINS-depleted extract containing Alexa Fluor 647-labeled recombinant GINS (GINSAF647), a subunit of CMG (Figure S2A). Extracts also contained fluorescent Fen1 (Fen1mKikGR) to image nascent DNA synthesis (Loveland et al., 2012). As reported previously (Sparks et al., 2019), total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy revealed GINSAF647 molecules moving at the leading edge of growing Fen1mKikGR tracts, demonstrating that GINSAF647 travels with active replication forks (Figures 2A,i, Supplemental Video 1). To generate a fluorescently labeled nick, we used a point mutant of Cas9, H840A ("nCas9"), which selectively nicks the non-target DNA strand (Jinek et al., 2012). nCas9 promoted efficient replication fork collapse (compare Figure S2B to Figure S1D). Furthermore, nCas9 RNPs labeled at the 5' end of the tracrRNA with Atto550 (nCas9Atto550; Figure 2B) bound specifically to the target site on the stretched DNA (Figure S2C). However, nCas9Atto550 dissociated at a significant rate upon exposure to extract (Figures S2D and S2E; (Wang et al., 2020)). Therefore, to increase the likelihood of fork collapse, nCas9Atto550 was targeted to 4 sites in the same strand located ~1 kb apart. In most cases, only 1-2 nCas9 molecules remained bound at the time of fork arrival. The cluster of nicks was positioned 5-8 kb from one end of the 30 kb DNA such that a fork traveling along the short arm underwent lead collapse when it collided with nCas9 (Figure 2A,ii, Supplemental Video 2).

Figure 2. CMG is lost at the nick after lead collapse.

(A) Tethered DNA was untreated (i), nicked with nCas9Atto550 (ii), or incubated with dCas9 Atto550 (iii) and replicated in extract containing Fen1mKikGR and GINSAF647. Representative kymographs are shown for each condition. For nCas9 (ii), we show kymographs where CMG approaches nCas9 from the short arm for lead collapse (in the left kymograph, the left nCas9 appears to dissociate before CMG arrival). CMG is shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, nCas9 in magenta. Although more than one Cas9 is frequently bound, only one is depicted in cartoons. Kymographs were created by stacking the frames of a movie (one-minute intervals). The DNA (white) and nCas9 (magenta) shown above each kymograph are from imaging the nCas9 and DNA before extract addition. Kymographs are generated from representative molecules from two biological replicates of each experiment. See also Supplemental Figure S2 and Supplemental Videos 1-3. (B) Schematic of nCas9 H840A bound to DNA with replication forks arriving from the left (lead collapse) or right (lag collapse).

In representative examples of lead collapse, CMG collided with nCas9, paused for a few minutes, and then disappeared (Figure 2A,ii). In 85% of such collisions, GINS dissociated from the chromatin at the nick site (Figure S2Fi,ii,vi). In contrast, when a catalytically dead mutant of Cas9 (dCas9) was targeted to these sites, CMG typically paused at dCas9 and then resumed replication upon dCas9 dissociation (Figure 2A,iii, Figure S2G,iii, and Supplemental Video 3), indicating that CMG loss upon encounter with nCas9 is due to the nick. Whether CMG is sufficient to remove Cas9 or cooperates with an accessory helicase such as Pif1(Schauer et al., 2020) or RTEL1(Sparks et al., 2019) is unclear. Consistent with a model in which CMG “runs off” the DNA end, GINSAF647 signal was lost at the same time as nCas9Atto550 45% of the time (Figure S2F,i). Surprisingly, GINSAF647 was lost before nCas9Atto550 33% of the time (Figure 2A,ii, right panel; Figure S2F,ii), demonstrating that the nCas9 tracrRNA sometimes retains its association with the target DNA even after CMG dissociates. Indeed, CMG should be able to slide off the leading strand template without disrupting the Cas9 RNP, which mostly forms contact with the lagging strand template (Figure 2B, lead collapse;(Jiang et al., 2016)). Instances in which CMG passes the nCas9 target site (Figure S2F,v) can mostly be attributed to the absence of a nick, as seen for dCas9, likely because nCas9 had not cleaved the DNA at the time of collision (see below). In summary, the loss of GINSAF647 at the nick site concurrent with or before nCas9 dissociation supports the model that CMG fully dissociates from the end of the break during lead collapse.

Lag collapse generates a seDSB with a 3’ ssDNA overhang

What happens to the replication fork during lag collapse is unknown. To address this question, we replicated a plasmid with TetR-protected nicks on the lagging strand template (top strand) (Figure S3A). As shown in Figure S3B, this yielded the same new band observed during lead collapse (lanes 7-12). To determine the structure of the seDSB generated during lag collapse, we cleaved nascent lagging strands 515 bp from the first nick (Figure 3A). Denaturing gel electrophoresis showed that their 5' ends were typically located 60-80 nucleotides from the break point (Figure 3A, purple bar), consistent with random initiation of the last Okazaki fragment relative to the nick. Therefore, lag collapse results in a seDSB break with a ~70 nt 3' ssDNA overhang. Analysis of the nascent leading strands revealed that they were extended to within a few nucleotides of each nick (Figures 3B and 3C), and some were extended a few nucleotides beyond the nick, consistent with limited strand displacement synthesis (Figures S3C and S3D). Given CMG's 20-40 nt footprint (Fu et al., 2011), this result argues that CMG does not stall when it first hits the nick (Figure 3B,i) because no stalling products were detected 20-40 nt upstream of the nick (Figure 3C). Moreover, leading strand arrest at the nick also rules out that CMG continues unwinding DNA well beyond the nick (Figure 3B,ii). Instead, the data suggest that CMG either rapidly dissociates at the nick (Figure 3B,iii), or that it somehow translocates beyond the nick without unwinding DNA (Figure 3B,iv), either of which would allow leading strand synthesis to reach the nick.

Active CMG unloading from double-stranded DNA during lag collapse

To distinguish between the latter two models, we examined the fate of fluorescent CMGs during lag collapse, which occurs when CMGs collide with nCas9Atto550 from the long arm of immobilized DNAs (Figure 4A, Supplemental Video 4). As seen for lead collapse (Figure 2A,ii), CMG typically paused at the nCas9, followed by rapid loss of nCas9 and CMG (Figure 4A, Veh.). However, far fewer CMGs were lost at the same time as nCas9 during lag collapse vs. lead collapse (4% vs. 45%; Figures. S2H,i and S2F,i), and more CMGs persisted longer than nCas9 for lag collapse compared to lead collapse (59% vs. 21%; Figures S2H,iii and S2F,iii). Together, our results demonstrate that CMG is lost from chromatin during lead and lag collapse, but the delayed CMG unloading during lag collapse suggested a more complex mechanism.

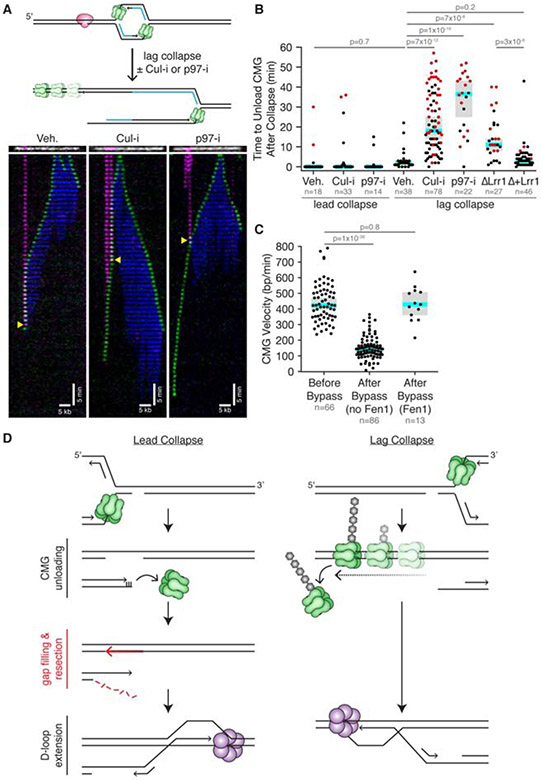

Figure 4. CRL2Lrr1-dependent CMG unloading from double-stranded DNA during lag collapse.

(A) Imaging was carried out as in Figure 2A,ii, except that we also included conditions with Cul-i and p97-i. We show representative kymographs of when CMG approaches nCas9 from the long arm, which involves lag collapse. Yellow triangle, moment of collapse (nCas9 loss). See also Supplemental Videos 4. In the middle kymograph, the left nCas9 appears to dissociate before arrival of CMG. (B) Distribution of CMG unloading times after lead and lag collapse in the indicated conditions. Because many CMGs persisted until the end of the 60 min experiment (red circles), the median times reported are lower limits. Although Lrr1 depletion did not appear to affect CMG behavior (Figure S2F) or unloading time during lead collapse, the data were not included because there were too few events for statistical significance. In (B) and (C), blue line is the median, and gray box represents the 95% confidence for the median determined from bootstrapping analysis. (C) Distribution of CMG velocities before and after nCas9 bypass with and without trailing Fen1 signal. Only velocities from the Cul-i and p97-i experiments were included because CMG needed to be retained for several minutes after collapse to accurately assess its velocity. All data from single molecule experiments are from two biological replicates. (D) Models for lead and lag collapse. Purple hexamer, putative helicase that replaces CMG for BIR. See also Figures S2 and S4.

We hypothesized that CMG unloading during lag collapse might resemble unloading during replication termination, in which converging CMGs undergo ubiquitylation by CRL2Lrr1 and unloading by the p97 ATPase (Figure S4A) (Dewar et al., 2017; Low et al., 2020). To test this idea, we supplemented extracts with the small molecule MLN4924 (“Cul-i”) to inhibit CRL2Lrr1 (Dewar et al., 2017), or we depleted Lrr1 from the extracts (Figure S4C). Strikingly, both Cul-i and Lrr1 depletion delayed CMG dissociation after collision with lagging strand nicks, and the retained CMG continued unidirectional DNA translocation beyond the collapse site (Figures 4A and 4B, Supplemental Video 4). Rapid CMG unloading was rescued in Lrr1-depleted extracts with recombinant CRL2Lrr1 (Figure 4B). NMS-873 (“p97-i”), an allosteric p97 inhibitor, also inhibited CMG unloading and promoted continued translocation beyond the nick (Figures 4A and 4B, Supplemental Video 4). Importantly, Cul-i and p97-i did not affect CMG loss during lead collapse (Figure 4B). These results show that CMG unloading during lag collapse, but not lead collapse, involves the CRL2Lrr1 ubiquitin ligase and the p97 ATPase, as seen during termination.

Recent evidence suggests that during replication termination, CMG translocates onto dsDNA before being unloaded (Dewar et al., 2015; Low et al., 2020). Our data suggest that a similar phenomenon occurs during lag collapse. When CMG translocated beyond a lagging strand nick under conditions where CMG unloading was inhibited (Lrr1 depletion, Cul-i or p97-i), no Fen1 signal was detected behind the helicase ~85% of the time (Figure S2H,ix). Similarly, no Fen1 signal was observed when CMG translocated beyond the nick in the absence of Cul-i and p97-i (Figures S4D and S2H,ix), but such events were rare because CMG was usually unloaded before it could travel far enough to assess Fen1’s behavior (Figures S4E and S2H,viii). Thus, CMG translocation beyond the nick after lag collapse is not associated with DNA synthesis. Moreover, after colliding with a lagging strand nick, CMG translocated three-fold slower than before the collision (Figure 4C; 144 bp/min vs. 422 bp/min). However, the rate of CMG progression was the same before and after encounter with nCas9 in the few instances in which Fen1 signal did trail behind CMG after the encounter (Figures 4C and S4F). Thus, we infer that the fork failed to undergo collapse in these cases (Figures S2F,ix and S2H,x). Fen1mKikGR did not affect CMG velocity before or after fork collapse (Figures S4G and S4H). Interestingly, whereas CMG slows down after lag collapse (Figure 4C), CMG does not slow after transitioning onto dsDNA during replication termination (Low et al., 2020). The reason for this difference is presently unclear. In summary, after CMG travels beyond a lagging strand nick, it translocates slowly and does not promote DNA synthesis. This strongly implies that CMG transitions onto dsDNA at the nick, which is consistent with biochemical experiments using purified CMG (Kang et al., 2012; Langston and O’Donnell, 2017). Together, the data argue that during lag collapse, CMG is removed from dsDNA via the same mechanism that operates during replication termination (Figures S4A and S4B).

Discussion

DNA replication forks sometimes collide with strand discontinuities before they are repaired. The frequency of these collisions is expected to increase when nicks are produced at an elevated rate (e.g. during oxidative stress) or when single strand break repair is impaired (e.g. PARP inhibitor treatment). We find that when forks encounter nicks in the leading strand template, CMG undergoes passive dissociation when it slides off the end of the break; at lagging strand nicks, CMG transitions onto dsDNA and is removed by the termination pathway, which involves ubiquitylation by CRL2Lrr1- and extraction by p97. CMG anchors most proteins to the fork, suggesting that the entire replisome is effectively disassembled at both kinds of nicks. Importantly, there is no known mechanism to re-assemble CMG de novo in S phase. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that after fork collapse, resumption of DNA synthesis requires nucleation of a BIR replisome around a new DNA helicase. Our results are consistent with studies that BIR involves Pif1 in yeast and possibly MCM8-9 in mammalian cells (Natsume et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2013). In summary, our data show that compared to most chemical adducts, strand discontinuities are uniquely dangerous DNA lesions that cause fork breakage and obligate replisome disassembly.

The question arises whether CMG can be recycled during other forms of replication stress. Based on single molecule imaging with yeast CMG, it was proposed that when replication stalls at DNA damage, CMG transitions onto dsDNA downstream of the damage; when repair is complete, CMG re-engages with the fork for replication restart (Wasserman et al., 2019). However, our data show that CMG is rapidly unloaded from dsDNA. Moreover, even if unloading could be prevented, CMG would translocate unidirectionally away from the stressed fork. Thus, our data suggest that in a cellular context, depositing CMG on dsDNA cannot be used to help the fork overcome DNA damage or to maintain the replisome during fork reversal.

Our nucleotide-resolution analysis of collapsed fork structures identifies at least two DNA processing steps that might be unique to the repair of leading strand collapsed forks (Figure 4D, left). First, the seDSB generated, being almost blunt, must be resected prior to homology-directed strand invasion. Second, on the unbroken sister chromatid, the gap between the 3' end of the nick and the final primed Okazaki fragment must be filled in to allow strand invasion by the resected end. In contrast, during lag collapse, gap filling is not required, and a ~70 nt ssDNA 3' overhang is automatically generated (Figure 4D, right) that is probably sufficient to promote strand invasion without further resection (Ira and Haber, 2002; Jakobsen et al., 2019). Our data predict that lead collapse repair might fail in genetic backgrounds that do not support resection (Nacson et al., 2020). In addition, the nearly blunt DNA end generated during lead collapse is an excellent binding site for Ku, suggesting that lead collapse should be more susceptible than lag collapse to NHEJ-dependent chromosomal translocations.

Recent evidence suggests that CMG ubiquitylation is suppressed during elongation by the excluded DNA strand, perhaps by preventing CRL2Lrr1 binding to the outer face of CMG(Deegan et al., 2020; Low et al., 2020). Suppression is lost when the excluded strand dissociates from CMG during termination (Fig 4D). Our finding that lag collapse triggers CRL2Lrr1-dependent CMG unloading strongly supports this model because the primary effect of CMG collision with a lagging strand nick is dissociation of the excluded strand from CMG. We hypothesize that CMG removal during replication termination and fork collapse serves the same purpose, namely, to prevent the interference of translocating CMGs with transcription and other chromatin-based processes.

Limitations

Stretching DNA templates for single molecule imaging impairs the chromatin assembly that normally occurs in cells and frog egg extracts. Therefore, our studies may not recapitulate effects of chromatin structure. For example, it is conceivable that CMG cannot translocate far beyond the nick site on nucleosomal DNA. However, it seems unlikely that chromatin would prevent CMG falling off or being unloaded at a nick. In addition, because we have not demonstrated that collapsed forks undergo repair in our system, it is unclear whether the structures we have described represent DNA repair intermediates. Future studies will address these limitations.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILIBILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Johannes Walter (johannes_walter@hms.harvard.edu).

Materials Availability

All materials used in this study will be made available upon request without any restrictions.

Data and code availability

All custom-written Matlab code and raw data will be made available upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Xenopus laevis

Xenopus laevis female frogs (Nasco, Cat# LM00535; age > 2 years) are used as a source of eggs for the preparation of extracts. Females are injected subcutaneously with human chorionic gonadotropin to induce ovulation. Males (Nasco, Cat# LM00715, age >1 year) are used as a source of sperm chromatin. All frogs are housed at 16°C in a satellite amphibian facility in the BCMP Department at Harvard Medical School in compliance with IACUC regulations. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Harvard Medical Area IACUC and conform to the relevant regulatory standards.

Insect Cell Lines

Sf9 (Expression Systems Cat# 94-001S) and Tni cells (Expression Systems Cat# 94-002S) were cultured in ESF 921 media (Fisher Scientific, Cat#96-001-01-CS) at 27°C for protein overexpression.

METHODS DETAILS

Preparation of nicked plasmids

The nicked plasmids used for the ensemble experiments were generated from a standard pBlueScript plasmid (pBS), with the following modifications. The pBS BspQI site was removed by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange kit (Agilent). New BspQI sites were added to the plasmids either 245 bp (to visualize the nascent leading strand) or 497 bp (to visualize the nascent lagging strand) away from the intended Tet-nick location using site-directed mutagenesis with the following primer sets: 1) 245 bp, 5’- ATGGTTCACGTAGTGGCTCTTCGCCATCGCCCTGATAGACG-3’ and 5'-GCCACTACGTGAACCATCACCCTAATCAAGTTTTTTGGGG-3'; 2) 494 bp, 5'-CCGAAAAGTGCCACGAAGAGCTGACGCGCCCTGTAGCG-3' and 5'-CGTGGCACTTTTCGGGGAAATGTGCGCGGAACCCC-3'. A BglII site was added to each plasmid where the Tet-nicks would be inserted using 5'-CCATTCGCCATTCAGAGATCTGCTGCGCAACTGTTG-3' and 5'-CAACAGTTGCGCAGCAGATCTCTGAATGGCGAATGG-3' primers. Next the plasmids were linearized with BglII and the first AflII-NheI-TetR-BbvCI-TetR-AvrII-NcoI site was added using Gibson assembly with the following sequence as a duplex (only one strand shown): 5’-CAATTTCCATTCGCCATTCAGACTTAAGGCTAGCTCTCTATCACTGATAGGGACCTCAGCTCTCTA TCACTGATAGGGACCTAGGCCATGGAGCTGCGCAACTGTTGGGAAGG-3’. Two additional repeats of these sequences were sequentially added by digesting with AvrII and ligating a NheI-TetR-BbvCI-TetR-AvrII insert into the plasmids. Finally, two 24x LacO arrays were added between the SacI and Kpn sites as previously described (Duxin et al., 2014).

Plasmids were then run on 0.8% agarose gels and the supercoiled DNA was extracted via electroelution. Purified plasmids were nicked with Nb.BbvCI or Nt.BbvCI for leading or lagging strand fork collapse, respectively. The plasmids were then gel purified by electroelution and stored at −20°C in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5. Plasmid pKV44 has an Nt.BspQI site positioned to nick the nascent leading strand 269 nt away from the first Nb.BbvCI nick site. Plasmid pKV45 has an Nt.BspQI site positioned to nick the nascent lagging strand 515 nt away from the first Nt.BbvCI nick site. pKV44 was used for all ensemble lead collapse experiments except when we wanted to visualize the lagging strand after lead collapse (then we nicked pKV45 with Nb.BspQI). pKV45 was used for all ensemble lag collapse experiments except when we wanted to visualize the leading strand after lag collapse (then we nicked pKV44 with Nt.BspQI). All restriction and nicking enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs and used according to manufacturer protocols.

Preparation of egg extracts

The methods for preparation of high-speed supernatant (HSS) and nucleoplasmic extracts (NPE) from Xenopus laevis eggs have been described previously (Lebofsky et al., 2009; Sparks and Walter, 2019; Walter et al., 1998). These references include detailed notes and images that are helpful for many of the extraction steps. Briefly, HSS was prepared from eggs collected from six adult female frogs. Eggs were de-jellied in 1 L 2.2% cysteine, pH 7.7, washed with 2 L 0.5x Marc’s Modified Ringer’s solution (MMR; 2.5 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.25 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 0.05 mM EDTA), and washed with 1 L Egg Lysis Buffer (ELB; 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.7, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM DTT, and 50 μg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma, Cat # C7698-5G)). Eggs were then packed in 14 mL round-bottom Falcon tubes (Fisher, Cat # 352059), supplemented with 5 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, and 2.5 μg/mL cytochalasin B (Sigma, Cat # C6762-10MG), and crushed by centrifugation with a swing-bucket rotor at 20,000xg for 20 min at 4°C in a Sorvall Lynx 4000 centrifuge (or equivalent). The low-speed supernatant (LSS) was collected by removing the soluble extract layer and supplemented with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide, 1 mM DTT, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 5 μg/mL cytochalasin B. This extract was then spun in thin-walled ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman, Cat # 347356) at 260,000xg for 90 min at 2°C in a tabletop ultracentrifuge with a swing-bucket rotor. Finally, lipids were aspirated off the top layer, and HSS was harvested, aliquoted, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

NPE preparation also began with extracting LSS, except eggs were collected from 20 female frogs, and the volumes used to de-jelly and wash the eggs were doubled (2 L 2.2% cysteine, 4 L 0.5x MMR, and 2 L ELB). LSS was supplemented with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide, 1 mM DTT, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 5 μg/mL cytochalasin B, and 3.3 μg/mL nocodazole. The LSS was then spun at 20,000xg in a swing-bucket rotor for 15 min at 4°C. The top, lipid layer was removed, and the cytoplasm was transferred to a 50 mL conical tube. Next, an ATP regenerating mix (2 mM ATP, 20 mM phosphocreatine, and 5 μg/mL phosphokinase) was added to the extract. Nuclear assembly reactions were initiated by adding demembranated Xenopus laevis sperm chromatin (Lebofsky et al., 2009) to a final concentration of 4,400/μL. After 75-90 min incubation, the nuclear assembly reactions were centrifuged for 2 min at 20,000xg at 4°C in a swinging-bucket rotor. The top, nuclear layer was then harvested and spun at 260,000xg for 30 min at 2°C. Finally, lipids were aspirated off the top layer, and NPE was harvested, aliquoted, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Protein expression and purification

Purification of biotinylated LacR (Dewar et al., 2015) was described in detail previously. LacR with a C-terminal AviTag and biotin ligase were co-expressed in T7 Express Cells (New England Biolabs) from pET11a and pBirAcm (Avidity) vectors, respectively. AviTag-LacR and biotin ligase expression were induced with 1 mM IPTG in media supplemented with 50 μM biotin to ensure efficient biotinylation of the AviTag-LacR. Cell pellets were lysed at room temperature in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% sucrose (w/v), cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche), 0.2 mg/mL lysozyme, 0.1% Brij 58). LacR in the insoluble fraction of the whole cell lysate was isolated by centrifugation at 4°C. Chromatin-bound LacR was then released from the DNA by sonication and addition of polymin P (1% final concentration). LacR was then precipitated with 37% ammonium sulfate, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 38% glycerol. Next, biotinylated LacR was affinity purified with SoftLink avidin resin (Promega) and dialyzed overnight (against 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 38% glycerol). LacR aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C.

GINS was purified as previously described (Sparks et al., 2019). Briefly, a bacmid containing all four GINS subunits, along with sequences encoding His- and sortase-tags on the C-terminus of Psf3, was transfected into Sf9 cells (Expression Systems, Cat # 94-001S). Baculovirus was amplified in three stages (P1, P2, and P3). GINS was expressed from 500 mL culture of Tni cells (Expression Systems, Cat # 94-002S) infected with P3 baculovirus. Cells were pelleted 48 h after infection and resuspended in GINS Lysis Buffer (GLB; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, EDTA-free cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Cat # 11873580001). The clarified lysate was isolated after centrifugation and incubated with NiNTA resin (QIAGEN, Cat # 30410) for 1 h at 4°C to bind the GINS complex. GINS was eluted from the resin with GLB containing 250 mM imidazole. Elutions were desalted using a PD10 column (GE Healthcare, Cat # 17-0851-01) into 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. GINS was further purified on a MonoQ column connected to an AKTA Pure FPLC with a 100-1000 mM NaCl gradient in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT buffer. Finally, GINS was desalted using PD10 columns, concentrated to 2 mg/mL, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

TetR has a His-tag and was purified using Ni-NTA resin as follows. The TetR expression plasmid (TetR gene from addgene plasmid 17492 cloned into pET28b) was transformed into BL21 cells in LB supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. A single colony from this transformation was used to inoculate LB supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, which was then grown to an OD600 of 0.5 at 37°C. Expression was induced by adding IPTG to 1 mM. After 3 h incubation, the cells were pelleted, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in 2 mL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT, 1 cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche), 1 mg/mL lysozyme) and rotated for 1 h at 4°C. Lysate was split into two 1.5 mL tubes and centrifuged in a microcentrifuge at 4°C at 13,000 RPM for 30 min. Supernatant was recovered and applied to equilibrated Ni-NTA resin. Samples were spun with Ni-NTA resin for 1 h at 4°C. Resin with lysate was added to a disposable column. Resin was washed twice with 4 mL of wash buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT). TetR was eluted from column with four, 0.5 mL additions of elution buffer (10 mL, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1mM DTT, 0.5 M Imidazole). DTT (5 mM) was added to samples immediately after eluting. TetR eluates were combined and dialyzed into 1 L of TetR dialysis buffer (81 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1.62 mM EDTA, 162 mM NaCl, 1.62 mM DTT) for 2 h at 4°C, then dialyzed into 1 L dialysis buffer overnight. Dialyzed samples were collected, and glycerol was added to bring the glycerol to 38% of total volume. Samples were aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

Ensemble fork collapse reactions

All ensemble replication reactions were carried out as previously described (Lebofsky et al., 2009), with notable changes mentioned below. Briefly, the replication reactions were performed by first pre-binding the plasmid with TetR and LacR, then licensing the DNA in HSS, and finally addition of NPE to initiate replication. One volume of plasmid DNA was pre-incubated with 3 volumes of LacR (23 μM) and 3 volumes of TetR (765 μM) for 20-30 min. After plasmid DNA was pre-bound with LacR and TetR, the DNA was licensed in HSS at a concentration of 6 ng/μL. DNA replication was initiated by mixing 1 volume of licensing mix with 2 volumes of NPE mix that was diluted up to 50% with 1x ELB-sucrose (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.7, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 250 mM sucrose). Reactions were carried out in the presence of [α-P32]dATP to radiolabel the replication products. For native agarose gels, reactions were stopped at indicated time points by mixing 1 μL of reaction mix with 6 μL replication stop buffer (8mM EDTA, 0.13% phosphoric acid, 10% ficoll, 5% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 80 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Then the proteins were digested with 1 μL of 20 mg/mL Proteinase K for 1 h at 37°C, and plasmids were run on a 0.8-1% agarose gel for ~2.5 h. Gels were then visualized by phosphorimaging on a Typhoon FLA 7000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Electron microscopy imaging of DNA structures

Ensemble fork collapse reactions were carried out as described above. After 15 min, 50 μL of reaction mix was stopped by addition to 420 μL extraction stop buffer. The stopped reactions were then RNase and proteinase K treated. DNA was purified by two rounds of phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. DNA was resuspended in 20 μL replication stop buffer and was run on a 0.8% agarose gel for 2 h. The gel was then stained with SYBR gold for 1 h to visualize the DNA, and DNA bands of interest were visualized and excised on a blue light box. DNA was electroeluted from the gel slices using an EluTrap system and concentrated with Amicon concentrators (0.5 mL, 100 kDa MWCO).

Five microliters of concentrated DNA were then mixed with 40 μL filtered water and 5 μL 2.5 M ammonium acetate. This mixture was incubated for 10 min. To these mixtures, 2 μL of 0.2 μg/μL cytochrome c solution was added. These solutions were then placed onto Parafilm as drops and allowed to incubate for 15 min. Next, we lightly touched parlodion-coated grids to the surface of the drops, and we dehydrated each grid in 50%, 75%, and 95% ethanol for 15 s each. Each grid was lightly touched to filter paper to dab off excess solution. In order to increase the contrast of the DNA, the grids were rotary shadowed in a Leica ACE600 with a platinum E-beam using the following parameters: 3° angle, 85 W power, 3 x 10−6 mbarr, and 3 nm Pt deposition. Finally, we carbon coated the grids to stabilize the parlodion film using the Leica ACE600 carbon E-beam set to the following parameters: 0° angle, 130 W power, 5 x10−6 mbarr, and 2 nm C deposition. Grids were examined with a FEI T12 transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with a Gatan 2k SC200 CCD camera at 40 kV or a JEOL 1200EX TEM equipped with a 2k CCD camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques).

Nascent strand analysis

To visualize the nascent strands on a denaturing gel, ensemble replication reactions were stopped at indicated time points by mixing 4-6 μL of reaction mix with 30 μL extraction stop buffer (0.5% SDS, 25 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) followed by addition of 5 μL 4 mg/mL RNase A, and incubation at 37°C for 45 min. Next, the proteins were digested with 5 μL of 20 mg/mL Proteinase K for at least 1.5 h at 37°C. Samples were then diluted to 145 μL with 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and DNA was extracted by phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitation.

Nascent DNA strands were either digested with Nt.BspQI or AflII to visualize the collapse products, as noted in the figure legends. First, ethanol precipitated DNA was resuspended in 5 μL 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5. Each of the digestion reactions was carried out using New England Biolabs enzymes and buffers at a final volume of 10 μL. The Nt.BspQI digestions were carried out with 1 Unit of Nt.BspQI in 1x NEB3.1 Buffer at 50°C for 1 h. The AflII digestions were carried out with 2 Units of AflII in 1x NEB CutSmart Buffer at 37°C for 1.5 h. All reactions were stopped with 5 μL Gel Loading Buffer II (Life Technologies, Cat # AM8547). Digested DNA was incubated at 75°C for 5 min before running on 4% (Nt.BspQI-digested samples) or 10% (AflII-digested samples) polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Gels were dried, exposed to phosphorscreens, and imaged on a Typhoon FLA 7000 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). The frequency of collapse at each of the collapse sites (Figure 1E) was corrected for the number of adenines expected for each product since products were visualized with [α-32P]dATP.

Sequencing gel ladders were prepared using Thermo Sequenase Cycle Sequencing Kits (USB, Cat # 78500 1KT) with the following primers: 5’-CCATCGCCCTGATAGACGG-3’ (Nt.BspQI, leading strand samples), 5’-TTAAGGCTAGCTCTCTATCACTG-3’ (AflII samples), or 5’-CGAAGAGCTGACGCGCCCTGTAGC-3’ (Nt.BspQI, lagging strand samples). The template DNA was either pKV44 for leading strand analysis or pKV45 for lagging strand analysis.

Preparation of nCas9 RNP complex

Guide RNA was prepared by annealing AltR CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA, ATTO 550 (IDT) with 10-fold excess Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA (IDT) in 1x Annealing Buffer (IDT) to yield 4 μM guide RNA (tracrRNA was limiting). The guide RNAs were then frozen at −20°C until needed for experiments. The crRNAs were designed to target specific sequences on the same strand of the 30 kb single molecule DNA (see below). Next, the Cas9 RNP complex was formed by mixing 25 pmol Alt-R S.p. Cas9 H840A Nickase V3 (IDT) with 2 pmol guide RNA in Cas9 binding buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) and incubating in the dark at room temperature for ~20 min before being used in experiments.

Single molecule fork collapse reactions

The single molecule replication assay, including flow cell assembly, immunodepletion of GINS from extracts, replication reaction conditions, and image acquisition, was described in detail previously (Sparks et al., 2019). Deviations from the previously published assay are described herein. Coverslips were passivated with 10% Biotin-PEG-SVA and m-PEG-SVA MW5000 (Laysan Bio.). The buffers used to stretch DNA, wash DNA, bind nCas9, and image DNA were degassed for at least 1 h prior to flowing into the flow cell. Flow cells were first incubated with 0.2 mg/mL streptavidin (Sigma) for at least 15 min. Next the flow cells were washed with 500 μL of DNA Blocking buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mg/mL BSA) + 0.5% Tween20 at 500 μL/min. Next, 500 μL of DNA solution containing 67 pg/μL DNA that was biotinylated at each end, DNA Blocking buffer + 0.05% Tween20 and 1.8 mM chloroquine was flowed into the cell at 100 μL/min to double tether the DNA to the coverslip. The flow cell was then equilibrated with 60 μL Cas9 binding buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) at 20 μL/min. Fifty microliters nCas9 solution was then added at 20 μL/min which contained the 2 nM nCas9 RNP (described above) in the Cas9 binding buffer. Initially, nCas9 bound specifically and nonspecifically across the entire length of the DNA. Site-specifically bound Cas9 molecules remain stably associated with DNA in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl (Sternberg et al., 2014). Therefore, to remove the nonspecifically bound nCas9, the flow cells were washed with 60 μL of Cas9 buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) at 20 μL/min. The flow cells were then re-equilibrated with 60 μL Cas9 buffer at 20 μL/min, before adding 30 μL of 200 nM Sytox Green (Thermo Fisher Cat# S7020) in Cas9 binding buffer at 20 μL/min to image the DNA and nCas9. Twenty to fifty fields of view (FOVs) were imaged for both Sytox and nCas9Atto550 using alternating 488 nm and 561 nm laser excitation three times (“pre-imaged DNA and nCas9”). Finally, DNA-bound sytox was washed off with 150 μL 1x ELB-sucrose at 10 μL/min. Single molecule replication experiments carried out without nCas9 were prepared using the same procedure except 150 μL of Cas9 binding buffer was flown into the cell at 20 μL/min after the DNA was added, followed by flowing in the Sytox solution, imaging the DNA, and flowing in the 1x ELB.

Endogenous GINS was immunodepleted in two rounds from HSS and three rounds from NPE (1 h each) at 4°C. The depleted extracts were used to make licensing, initiation, and replication mixes as previously described (Sparks et al., 2019) at room temperature. The double-tethered, nCas9-bound DNA was licensed by flowing in 20 μL of GINS-depleted HSS licensing mix at 10 μL/min and incubating for 4-15 min. Replication was then initiated with 20 μL of GINS-depleted HSS/NPE initiation mix that included 0.01 mg/mL recombinant GINSAF647, 2 μM Fen1-mKikGR D179A, and 3.7 nM nCas9Atto550 at 10 μL/min. After 4 min, 50 μL of a new GINS-depleted HSS/NPE replication mix was flown in at 10 μL/min that included 2 μM Fen1-mKikGR D179A, but did not include GINSAF647 or nCas9Atto550 to remove fluorescence background from excess proteins. The absence of nCas9 in the final replication mix prevents rebinding of nCas9 during the collapse reactions. Where indicated, p97-i (NMS-873, Sigma) or Cul-i (MLN4924, Active Biochem) inhibitors were added to the initiation and replication mixes at a final concentration of 200 μM. Images of Fen1-mKikGR, nCas9Atto550, and GINSAF647 were acquired every minute for 1 h by cycling among the 488 nm (64-65° TIRF angle, 0.23 mW, 100 ms exposure, 999 EM GAIN), 561 nm (61-63° TIRF angle, 0.35 mW, 100 ms exposure, 999 EM GAIN), and 647 nm (61-63° TIRF angle, 0.15 mW, 100 ms exposure, 999 EM GAIN) lasers at each of the fields of view. Specific microscope configurations were previously described (Sparks et al., 2019). Movies were collected using NIS Elements software and saved as nd2 files.

Single molecule data analysis

All image analysis was performed using a combination of freely available and custom Matlab scripts. Movie files were imported into a graphical user interface (GUI) using Bio-Formats to convert the nd2 files into readable metadata and matrices (Linkert et al., 2010). The movies were then stabilized to remove drift using a Matlab script for efficient subpixel image registration (Guizar-Sicairos et al., 2008). The nCas9 was targeted to the DNA asymmetrically to divide the DNA into short and long arms relative to the nicking site. To determine which side of the DNA the nCas9 was binding to, the nCas9 channel from the “pre-imaged DNA and nCas9” (described above) with the nCas9 channel from the replication movie was aligned using the same subpixel image registration script. The brightness and contrast of the movies were adjusted for each channel in Matlab. The max projection of the CMG signal was overlaid with the image of the unreplicated DNA (acquired before addition of extract) to identify which DNA molecules were replicated. Then DNA molecules of interest were manually selected to assemble kymographs. Molecules were chosen based on three criteria: 1) multiple DNA molecules did not overlap significantly with each other, 2) nCas9Atto550 signal was correctly positioned on the DNA, and 3) the DNA appeared to be nearly fully stretched. The kymographs were then categorized according to the type of events observed, as shown in Figures S2F, S2G, and S2H. CMG velocities were determined from the linear fit of the center position of the GINSAF647 signal over time. These signal positions were determined using a modified version of the u-track Matlab software (Jaqaman et al., 2008). The time to unload CMG after collapse was determine by counting the number of frames until GINSAF647 signal was lost (1 min each) after nCas9Atto550 signal was lost. The time to unload CMG was counted as zero minutes for the events in which CMG and nCas9 appeared to be lost at the same time.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All ensemble experiments were repeated three or more times. All single molecule experiments were performed two or more times. All image analysis, including replication and sequencing gels and single molecule movies, was performed using Matlab. The Kaplan-Meier curve in Figure S2E was generated using Matlab’s built-in empirical cumulative distribution function (ecdf). Error bars were generated from three individual biological replicates. P values were calculated using Matlab’s two-sample t-test function. Additional relevant statistical details are mentioned in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1. Replication of unnicked DNA. Replication of a single, double tethered DNA was visualized by TIRF microscopy. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,i.

Supplemental Video 2. Leading strand fork collapse. Collision of a replication fork arriving from the short arm with nCas9 results in leading strand fork collapse. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, nCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,ii.

Supplemental Video 3. Replication fork encounter with dCas9. Unlike leading strand fork collapse, in which CMG is lost at the nCas9, CMG bypasses dCas9 and replication continues. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, dCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,iii.

Supplemental Video 4. Lagging strand fork collapse. Collision of a replication fork arriving from the long arm with nCas9 results in lagging strand fork collapse. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, nCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymographs in Figure 4A.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit Anti-GINS; Antigen: purified GINS complex | Sparks et al., 2019 | N/A |

| Rabbit Anti-Lrr1; Antigen: ACYQFLDKYLQSTRV | Dewar et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| [α-32P]dATP | Perkin Elmer | Cat# BLU512H500UC |

| ATP | Sigma | Cat# A-5394 |

| Phosphocreatine | Sigma | Cat# P-6502 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase | Sigma | Cat# C-3755 |

| High Speed Supernatant (HSS) | Sparks and Walter, 2018 | N/A |

| Nucleoplasmic Extract (NPE) | Sparks and Walter, 2018 | N/A |

| Proteinase K | Roche | Cat# 3115879001 |

| RNase | Sigma | Cat# R4642-250mg |

| GINS expressed from pGC128 | Sparks et al., 2019 | N/A |

| Fen1mKikGR | Loveland et al., 2012 | N/A |

| LacI-biotin | Dewar et al., 2015 | N/A |

| p97-i (NMS873) | Sigma | Cat# SML 1128 |

| Cul-i (MLN4924) | Active Biochem | Cat# A-1139 |

| IPTG | Sigma | Cat# I5502 |

| Leupeptin | Roche | Cat# 11529048001 |

| Aprotinin | Roche | Cat# 11583794001 |

| BSA | Fisher | Cat# BP1600-100 |

| L-cysteine | Fisher | Cat# ICN10144601 |

| Cycloheximide | Sigma | Cat# C7698-5G |

| Cytochalasin B | Sigma | Cat# C6762-10MG |

| 14 mL Round-bottom falcon tubes | Fisher | Cat# 352059 |

| 2.5 mL thin-walled ultracentrifuge tubes | Beckman | Cat# 347356 |

| Nocodazole | Sigma | Cat# M1404-10MG |

| EDTA-free cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail | Roche | Cat# 11873580001 |

| Nb.BbvCI | NEB | Cat# R0631S |

| Nt.BbvCI | NEB | Cat# R0632S |

| Nt.BspQI | NEB | Cat# R0644S |

| AflII | NEB | Cat# R0520S |

| NcoI | NEB | Cat# R0193L |

| MfeI-HF | NEB | Cat# R3589S |

| Klenow Fragment, exo- | NEB | Cat# M0212S |

| AlexaFluor647-maleimide | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A20347 |

| SYTOX Green | Thermo Fisher | Cat# S7020 |

| PD10 desalting column | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17-0851-01 |

| NiNTA resin | QIAGEN | Cat# 30410 |

| Streptavidin-coupled magnetic Dynabeads M-280 | Invitrogen | Cat# 11206D |

| Protein A Sepharose Fast Flow | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17127903 |

| Biotin-PEG-SVA | Laysan Bio | Cat# Bio-PEG-SVA-5k-100mg |

| M-PEG-SVA MW5000 | Laysan Bio | Cat# MPEG-SVA-5K-1g |

| Alt-R S.p. Cas9 H840A Nickase V3, 100 μg | IDT | Cat# 1081064 |

| Alt-R S.p. dCas9 Protein V3, 100 μg | IDT | Cat# 1081066 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 10359016 |

| MultiBac Expression System Kit | Geneva Biotech | Cat# MultiBac |

| ZR BAC DNA miniprep kit | Zymo Research | Cat# D4048 |

| Thermo Sequenase Cycle Sequencing Kits | USB | Cat# 78500 1KT |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Sf9 Insect Cells | Expression Systems | Cat#94-001S |

| Tni Insect Cells | Expression Systems | Cat#94-002S |

| T7 Express Cells | NEB | Cat# C2566I |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Xenopus laevis, adult female | Nasco | Cat# LM00535 |

| Xenopus laevis, adult male | Nasco | Cat# LM00715 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT (22 kb site, 5’-CAUGCCGUCACCCUAUUACA-3’) | This study (ordered from IDT) | N/A |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT (23 kb site, 5’-CAGGCGCUCCAUUGCCCAGU-3’) | This study (ordered from IDT) | N/A |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT (24 kb site, 5’-UGCCUGAGGCCAGUUUGCUC-3’) | This study (ordered from IDT) | N/A |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT (25 kb site, 5’-CCAGGUUCAACGGGCATGTA-3’) | This study (ordered from IDT) | N/A |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA, ATTO550 | This study (ordered from IDT) | Cat# 1075927 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pKV44 | This study | N/A |

| pKV45 | This study | N/A |

| pGC261 | Sparks et al., 2019 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| NIS Elements | Nikon Instruments | https://www.nikoninstruments.com/Products/Software |

| MATLAB | Mathworks | https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html |

| Bio-Formats | Linkert et al., 2010 | https://www.openmicroscopy.org/bio-formats/ |

| Image registration | Guiz-Sicairos et al., 2008 | https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.33.000156 |

| Molecule tracking script (u-track) | Jaqaman et al., 2008 | https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/labs/danuser/software/ |

Highlights.

The structures of leading and lagging strand collapsed forks are different

CMG passively “runs off” the broken DNA end during leading strand fork collapse

CMG removal from duplex DNA after lag collapse depends on CRL2Lrr1 and p97

Nicks are uniquely toxic lesions that cause fork collapse and replisome disassembly

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Pellman, J. Haber, and members of the Walter laboratory for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank Manal Zaher for advice and CRL2Lrr1. Initial single molecule experiments were conducted at the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School with assistance from Jennifer Waters. Electron microscopy experiments were conducted at the Electron Microscopy Facility at Harvard Medical School with assistance from Maria Ericsson. This work was supported by NIH Grants HL098316 and GM80676. K.B.V. and R.A.W. were supported by American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowships. G.C. was supported by the Jane Coffin Childs memorial fund. J.C.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

J.C.W. is a co-founder of MoMa therapeutics, in which he has a financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Caldecott KW (2008). Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 9, 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan TD, Mukherjee PP, Fujisawa R, Polo Rivera C, and Labib K (2020). CMG helicase disassembly is controlled by replication fork DNA, replisome components and a ubiquitin threshold. ELife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar JM, Budzowska M, and Walter JC (2015). The mechanism of DNA replication termination in vertebrates. Nature 525, 345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar JM, Low E, Mann M, Räschle M, and Walter JC (2017). CRL2Lrr1 promotes unloading of the vertebrate replisome from chromatin during replication termination. Genes and Development 31, 275–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilley RL, Verma P, Cho NW, Winters HD, Wondisford AR, and Greenberg RA (2016). Break-induced telomere synthesis underlies alternative telomere maintenance. Nature 539, 54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxin JP, Dewar JM, Yardimci H, and Walter JC (2014). Repair of a DNA-protein crosslink by replication-coupled proteolysis. Cell 159, 349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. v., Yardimci H, Long DT, Ho V, Guainazzi A, Bermudez VP, Hurwitz J, van Oijen A, Walter JC, Schärer OD, et al. (2011). Selective bypass of a lagging strand roadblock by the eukaryotic replicative DNA helicase. Cell 146, 931–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizar-Sicairos M, Thurman ST, and Fienup JR (2008). Efficient subpixel image registration algorithms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE (1999). DNA recombination: The replication connection. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 24, 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakem R, de La Pompa JL, Sirard C, Mo R, Woo M, Hakem A, Wakeham A, Potter J, Reitmair A, Billia F, et al. (1996). The tumor suppressor gene Brca1 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Cell 85, 1009–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Puddu F, and Costanzo V (2012). RAD51- and MRE11-dependent reassembly of uncoupled CMG helicase complex at collapsed replication forks. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 19, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengel SR, Spies MA, and Spies M (2017). Small-Molecule Inhibitors Targeting DNA Repair and DNA Repair Deficiency in Research and Cancer Therapy. Cell Chemical Biology 24, 1101–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg M, Osterman P, Bylund GO, Ganai RA, Lundström EB, Sauer-Eriksson AE, and Johansson E (2014). Structural basis for processive DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase É. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 21, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, and Haber JE (2002). Characterization of RAD51-Independent Break-Induced Replication That Acts Preferentially with Short Homologous Sequences. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22, 6384–6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen KP, Nielsen KO, Løvschal K. v, Rødgaard M, Andersen AH, and Correspondence LB (2019). Minimal Resection Takes Place during Break-Induced Replication Repair of Collapsed Replication Forks and Is Controlled by Strand Invasion. CellReports 26, 836–844.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaqaman K, Loerke D, Mettlen M, Kuwata H, Grinstein S, Schmid SL, and Danuser G (2008). Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nature Methods 5, 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Taylor DW, Chen JS, Kornfeld JE, Zhou K, Thompson AJ, Nogales E, and Doudna JA (2016). Structures of a CRISPR-Cas9 R-loop complex primed for DNA cleavage. Science 351, 867–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, and Charpentier E (2012). A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YH, Galal WC, Farina A, Tappin I, and Hurwitz J (2012). Properties of the human Cdc45/Mcm2-7/GINS helicase complex and its action with DNA polymerase ε in rolling circle DNA synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 6042–6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston L, and O’Donnell M (2017). Action of CMG with strand-specific DNA blocks supports an internal unwinding mode for the eukaryotic replicative helicase. ELife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebofsky R, Takahashi T, and Walter JC (2009). DNA replication in nucleus-free xenopus egg extracts. Methods in Molecular Biology 521, 229–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkert M, Rueden CT, Allan C, Burel JM, Moore W, Patterson A, Loranger B, Moore J, Neves C, MacDonald D, et al. (2010). Metadata matters: Access to image data in the real world. Journal of Cell Biology 189, 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland AB, Habuchi S, Walter JC, and van Oijen AM (2012). A general approach to break the concentration barrier in single-molecule imaging. Nature Methods 9, 987–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low E, Chistol G, Zaher MS, Kochenova O. v., and Walter JC (2020). The DNA replication fork suppresses CMG unloading from chromatin before termination. Genes & Development 34, 1534–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydeard JR, Lipkin-Moore Z, Sheu Y-J, Stillman B, Burgers PM, and Haber JE (2010). Break-induced replication requires all essential DNA replication factors except those specific for pre-RC assembly. Genes & Development 24, 1133–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayle R, Campbell IM, Beck CR, Yu Y, Wilson M, Shaw CA, Bjergbaek L, Lupski JR, and Ira G (2015). Mus81 and converging forks limit the mutagenicity of replication fork breakage. Science 349, 742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacson J, di Marcantonio D, Wang Y, Sykes SM, Johnson N, Nacson J, di Marcantonio D, Wang Y, Bernhardy AJ, Clausen E, et al. (2020). BRCA1 Mutational Complementation Induces Synthetic Viability Short Article BRCA1 Mutational Complementation Induces Synthetic Viability. Molecular Cell 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsume T, Nishimura K, Minocherhomji S, Bhowmick R, Hickson ID, and Kanemaki MT (2017). Acute inactivation of the replicative helicase in human cells triggers MCM8–9-dependent DNA synthesis. Genes and Development 31, 816–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen I, Bentsen IB, Lisby M, Hansen S, Mundbjerg K, Andersen AH, and Bjergbaek L (2009). A Flp-nick system to study repair of a single protein-bound nick in vivo. Nature Methods 6, 753–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GD, Spenkelink LM, Lewis JS, Yurieva O, Mueller SH, van Oijen AM, and O’Donnell ME (2020). Replisome bypass of a protein-based R-loop block by Pif1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharan SK, Morimatsu M, Albrecht U, Lim DS, Regel E, Dinh C, Sands A, Eichele G, Hasty P, and Bradley A (1997). Embryonic lethality and radiation hypersensitivity mediated by Rad51 in mice lacking Brca2. Nature 386, 804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville R, Bhowmick R, Hoffmann S, Mailand N, Hickson ID, and Labib K (2019). TRAIP drives replisome disassembly and mitotic DNA repair synthesis at sites of incomplete DNA replication. ELife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Buerstedde J-M, Bezzubova O, Shinohara A, Ogawa H, Takata M, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takeda S, and Chair B (1998). Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks J, and Walter JC (2019). Extracts for Analysis of DNA Replication in a Nucleus-Free System. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2019, pdb.prot097154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks JL, Chistol G, Gao AO, Mann M, Duxin JP, and Correspondence JCW (2019). The CMG Helicase Bypasses DNA-Protein Cross-Links to Facilitate Their Repair. Cell 176, 167–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, and Doudna JA (2014). DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumberg D, Pilon AA, Smith M, Hickey R, Malkas L, and Pommier Y (2000). Conversion of Topoisomerase I Cleavage Complexes on the Leading Strand of Ribosomal DNA into 5’-Phosphorylated DNA Double-Strand Breaks by Replication Runoff. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20, 3977–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki T, Fujii Y, Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Nakao K, Sekiguchi M, Matsushiro A, Yoshimura Y, and Morita T (1996). Targeted disruption of the Rad51 gene leads to lethality in embryonic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93, 6236–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilenchik MM, and Knudson AG (2003). Endogenous DNA double-strand breaks: Production, fidelity of repair, and induction of cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 12871–12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter JC, Sun L, and Newport J (1998). Regulated chromosomal DNA replication in the absence of a nucleus. Molecular Cell 1, 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AS, Chen LC, Wu RA, Hao Y, McSwiggen DT, Heckert AB, Richardson CD, Gowen BG, Kazane KR, Vu JT, et al. (2020). The histone chaperone FACT induces Cas9 multi-turnover behavior and modifies genome manipulation in human cells. Molecular Cell In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman MR, Schauer GD, O’Donnell ME, and Liu S (2019). Replication Fork Activation Is Enabled by a Single-Stranded DNA Gate in CMG Helicase. Cell 178, 600–611.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Kwon Y, Xu Y, Chung W-H, Chi P, Niu H, Mayle R, Chen X, Malkova A, Sung P, et al. (2013). Pif1 helicase and Polδ promote recombination-coupled DNA synthesis via bubble migration. Nature 502, 393–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1. Replication of unnicked DNA. Replication of a single, double tethered DNA was visualized by TIRF microscopy. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,i.

Supplemental Video 2. Leading strand fork collapse. Collision of a replication fork arriving from the short arm with nCas9 results in leading strand fork collapse. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, nCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,ii.

Supplemental Video 3. Replication fork encounter with dCas9. Unlike leading strand fork collapse, in which CMG is lost at the nCas9, CMG bypasses dCas9 and replication continues. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, dCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymograph in Figure 2A,iii.

Supplemental Video 4. Lagging strand fork collapse. Collision of a replication fork arriving from the long arm with nCas9 results in lagging strand fork collapse. CMG shown in green, Fen1mKikGR in blue, nCas9 in magenta. Frames collected every minute for 1 h. Corresponding kymographs in Figure 4A.

Data Availability Statement

All custom-written Matlab code and raw data will be made available upon request.