Abstract

Background

Sterile processing departments (SPDs) play a crucial role in surgical safety and efficiency. SPDs clean instruments to remove contaminants (decontamination), inspect and reorganise instruments into their correct trays (assembly), then sterilise and store instruments for future use (sterilisation and storage). However, broken, missing or inappropriately cleaned instruments are a frequent problem for surgical teams. These issues should be identified and corrected during the assembly phase.

Objective

A work systems analysis, framed within the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model, was used to develop a comprehensive understanding of the assembly stage of reprocessing, identify the range of work challenges and uncover the inter-relationship among system components influencing reliable instrument reprocessing.

Methods

The study was conducted at a 700-bed academic hospital in the Southeastern United States with two reprocessing facilities from October 2017 to October 2018. Fifty-six hours of direct observations, 36 interviews were used to iteratively develop the work systems analysis. This included the process map and task analysis developed to describe the assembly system, the abstraction hierarchy developed to identify the possible performance shaping factors (based on SEIPS) and a variance matrix developed to illustrate the relationship among the tasks, performance shaping factors, failures and outcomes. Operating room (OR) reported tray defect data from July 2016 to December 2017 were analysed to identify the percentage and types of defects across reprocessing phases the most common assembly defects.

Results

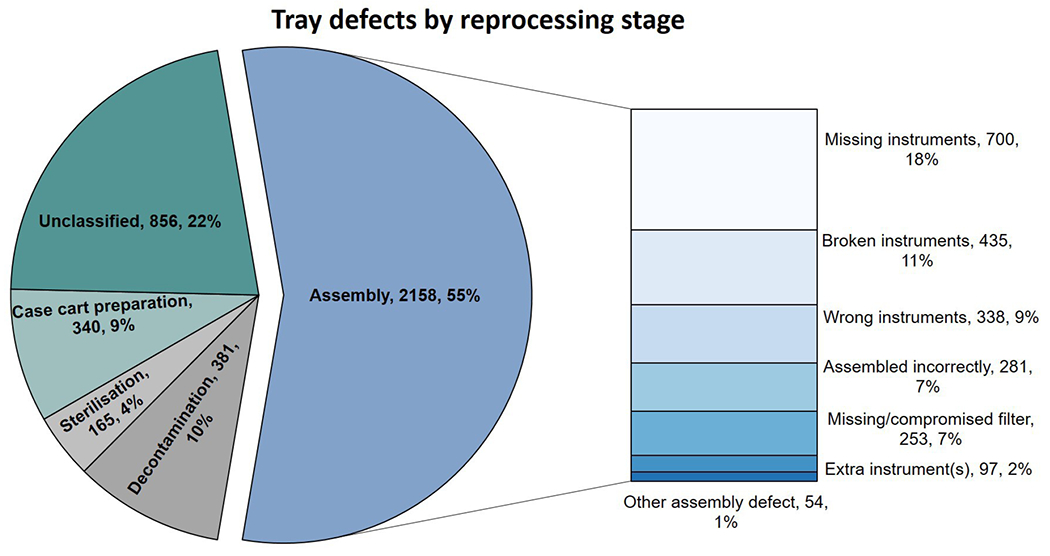

The majority of the 3900 tray defects occurred during the assembly phase; impacting 5% of surgical cases (n=41 799). Missing instruments, which could result in OR delays and increased surgical duration, were the most commonly reported assembly defect (17.6%, n=700). High variability was observed in the reassembling of trays with failures including adding incorrect instruments, omitting instruments and failing to remove damaged instrument. These failures were precipitated by technological shortcomings, production pressures, tray composition, unstandardised instrument nomenclature and inadequate SPD staff training.

Conclusions

Supporting patient safety, minimising tray defects and OR delays and improving overall reliability of instrument reprocessing require a well-designed instrument tracking system, standardised nomenclature, effective coordination of reprocessing tasks between SPD and the OR and well-trained sterile processing technicians.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 51.4 million inpatient surgeries are conducted annually in the USA.1 After each procedure reusable instruments are sent to the sterile processing department (SPD) to be reprocessed for future use. First, instruments are cleaned to remove all contaminants and bodily fluids (decontamination), then the instruments are inspected and reorganised into their correct trays (assembly) which are sterilised chemically or with heat (sterilisation) to ensure they are free from microorganisms and bacteria, and the trays are stored for future use (storage).2 Since surgical instruments are cleaned and reused multiple times per week for many years, reprocessing must be rapid, efficient and reliable. Extant literature on instrument reprocessing has focused predominantly on technical aspects of the decontamination and sterilisation processes for infection control.3–5 However, the most commonly reported errors in reprocessing involve missing and damaged instruments; issues that could be identified and corrected during the assembly process.2 The present study examines systemic challenges in instrument reprocessing focusing on the assembly stage.

An effective assembly process results in neatly organised trays, containing the count sheet (list of instruments in the tray), chemical indicators (to confirm sterility) and all of the specified instruments, functional and free of contaminants. Around 1 in 10 instrument trays are delivered to the operating room (OR) from SPD with missing instruments, with another 1 in 20 containing broken instruments.2 These tray defects can result in increased risk to the patient, delays in surgery and substantial costs for the hospital.6–8 Immediate use sterilisation, if a replacement instrument requires reprocessing, carries a higher potential for surgical site infections.9 Using a different instrument can introduce new risks, delays or deviations.10 Case cancellations cost $1500 or more per hour of planned surgery.11 Instrument defects can also result in direct patient harm: loose screws or instrument parts can lead to retained objects; blunt instruments can tear skin or tissue; clamps with cracked hinges can harbour infections; and poor insulation on graspers can lead to burns.12,13

Typically, reprocessing issues, such as missing and damaged instruments, are blamed on deficient culture of safety; inadequate oversight; lack of knowledge or training; inaccessible guidelines; and poor monitoring and tracking.14 However, this analysis seems simplistic given that pressures to quickly turn around instruments can lead to short cuts, instrument designs may not facilitate reprocessing,15,16 manufacturer’s instructions for use for reprocessing are often lengthy and unclear,17–19 and the working environment can be hot, humid, noisy and distraction prone.20 These causes suggest deeper systemic issues within SPDs, rather than poor individual performance or safety culture alone. Examining how these systemic influences lead to different types of outcomes could lead to safer and more efficient instrument reprocessing.21,22

We saw an SPD as an example of a sociotechnical system, where people, procedures, technology, environment and organisation interact to produce a range of proximal and distal outcomes.21 Work systems analysis (WSA) refers to a collection of analytical processes that use mixed methods to understand sociotechnical systems by describing the tasks and components, defining boundaries, identifying hazards and modelling performance variations across a broad system of work.20,23–26 While more familiar engineering approaches such as failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) and process mapping can be useful for specific linear tasks, WSA combines multiple approaches to model dynamic, non-linear systems at a higher organisational level. WSA approaches have been applied to a range of complex healthcare performance problems,25,27,28 including a sterile processing environment,25 with an identical approach successfully applied to the decontamination, sterilisation and case cart preparation stages of reprocessing.15,29 This was augmented with the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS), a framework describing and classifying multiple levels of a clinical system (person, tasks, tools and technology, organisation and environment) to support the broad examination of the system components and their interactions.26 By using WSA within this commonly used systems engineering framework26 we aimed to develop a comprehensive understanding of the SPD assembly work system by uncovering key relationships between system components, and the sources of variance that might influence reliable assembly in instrument reprocessing.30,31

METHODS

Study setting

The study was conducted from October 2017 to October 2018 at a 700-bed academic hospital in the Southeastern United States. The hospital maintained two SPD facilities that reprocessed instruments for 31 ORs, 9 ambulatory centres and 56 on-site clinics. The facilities employed a total of 89 staff and reprocessed roughly 23 000 instrument trays per month. The research was conducted primarily at the main facility and differences at the secondary facility were noted. Institutional Review Board approval was not required. Three other SPDs at different health systems—a non-academic hospital, a children’s hospital and a hospital with an off-site reprocessing facility—were also observed to inform the generalisability of the findings and identify potential interventions.

Data collection

A WSA approach requires the use of mixed methods including observations, interviews, reviews of regulations, guidelines and processes, and access to performance data. Data collection was structured to facilitate the iterative development of the WSA, which included a process map, task analysis, abstraction hierarchy and variance matrix. Direct observations of reprocessing tasks were conducted once or twice per week for 22 weeks resulting in a total of 48 hours of observations at the main site. We conducted morning and day shift observations and various technicians were observed over the 22-week period; however, we did not record this number. Several technicians were observed on multiple occasions. Observations continued until our models contained the level of detail desired and were validated by SPD staff and management. An additional 2–3 hours of observations were conducted at each external site. Observations were conducted by a postdoctoral researcher with a background in human factors engineering (MA). Several observations were conducted jointly with an experienced human factors practitioner (KC) and an undergraduate researcher studying industrial engineering (EH). The observational methodology specified a ‘thicker’ note-taking approach to facilitate the development of a work systems model of instrument reprocessing and identify sociotechnical challenges in the assembly process.32 This approach attempts to identify a collection of concepts that initial observations reveal to be important, provide an opportunity to explore the deeper meaning of the data collected, allow further study and complement numerical results.32 Semistructured interviews were conducted by one to two researchers with a broad range of staff including technicians (n=18), SPD supervisors (3), SPD managers (3), SPD educators (2) and hospital staff in safety (2), performance improvement (2), infection control (2) and perioperative services (1). The questions, which were not limited to assembly but the full gamut of SPD work, concerned current reprocessing issues, point-of-use reprocessing, process and outcome data used, SPD training and education and previous improvement initiatives. Questions for SPD staff also included their daily work, issues they frequently encounter and feedback they receive. SPD managers at the three external sites were interviewed about their challenges, technician training and the process and outcome data they collect and use to support decision-making. Notes were taken during the interviews but they were not recorded. Pictures and videos were also used to keep track of detailed information and processes and standard operating procedures, policies, training material and regulatory documents were also reviewed.

WSA development

First, the basic system description of SPD processes and functions identified physical and procedural distinctions between assembly and the other stages of reprocessing. We then created a process map using the notes from our observations and interviews to define the flow of trays through assembly. A detailed representation of each assembly task and the human actions required to enact each step in the process were defined in a hierarchical task analysis.33,34 Ad hoc interviews for further detailed enquiry were conducted with sterile processing technicians and supervisors. We iteratively refined the process map and hierarchical task analysis with the assistance of the technicians and an expert group—including representation from SPD, risk and safety, performance improvement and infection control. Pictures and videos were used to capture the state of the trays, workspaces and assembly processes.

Observation and interview notes were summarised into a system description of assembly, which included stakeholders, boundaries and the sociotechnical dimensions. An abstraction hierarchy was then created to illustrate the multilevel sociotechnical factors that influence performance and lead to variations in assembly processes and outcomes.26,31,35,36 In addition to the observations and interviews, the development of the model required the review of relevant organisational and regulatory policies affecting task performance. The levels of the hierarchy—task, tools and technology, person, internal environment, organisation and external environment—were based on the SEIPS model.26 We then identified the factors—including support tools, equipment maintenance; space and layout, standard operating procedures; feedback and communication; staffing and turnover; and environmental factors—that affected performance and classified them in their corresponding level in the hierarchy. These models, the process map, task analysis and abstraction hierarchy, were iterated based on feedback from SPD staff.

The variance matrix was then developed to identify how performance of the tasks is shaped by the proximal system factors identified in the abstraction hierarchy. These factors, described as performance shaping factors, were also classified based on SEIPS and included person (knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSAs)), tools and technology (workstation), internal environment (inventory), organisation (OR production pressure) and external environment (instrument design).26 Next, we identified the task failures and their effects on subsequent processes and outcomes. Failure modes were identified through observation, interviews, review of standard operating procedures and training documents, and through the tray defect data, which define tray defects by their failure (eg, missing instrument, broken instrument and bioburden on instrument). We also noted various interventions employed at the four sites to alleviate undesired outcomes, but did not evaluate their efficacy. The variance matrix illustrates how poor outcomes such as damaged, incorrect and missing instruments, and OR delays, may occur through various task failures that are predisposed by the design of the system.

Tray defect data analysis

Tray defects are the primary outcome data used by SPDs to assess performance. These data, derived and aggregated from OR reports, were obtained from hospital administration, covering the period from 1 July 2016 to 31 December 2017. Data were analysed by defect type (as defined within the report), with types grouped by consensus among two coders into the phase where the defect likely arose (assembly, decontamination, sterilisation and case cart preparation). This was performed using the tray defect description (eg, missing count sheet, missing chemical indicator (external) and the task analyses of the different reprocessing phases). Total cases performed during the period, also derived from hospital administrative databases, were used as a denominator to determine the percentage of cases with at least one defective tray.

RESULTS

Basic system description, process map and hierarchical task analysis

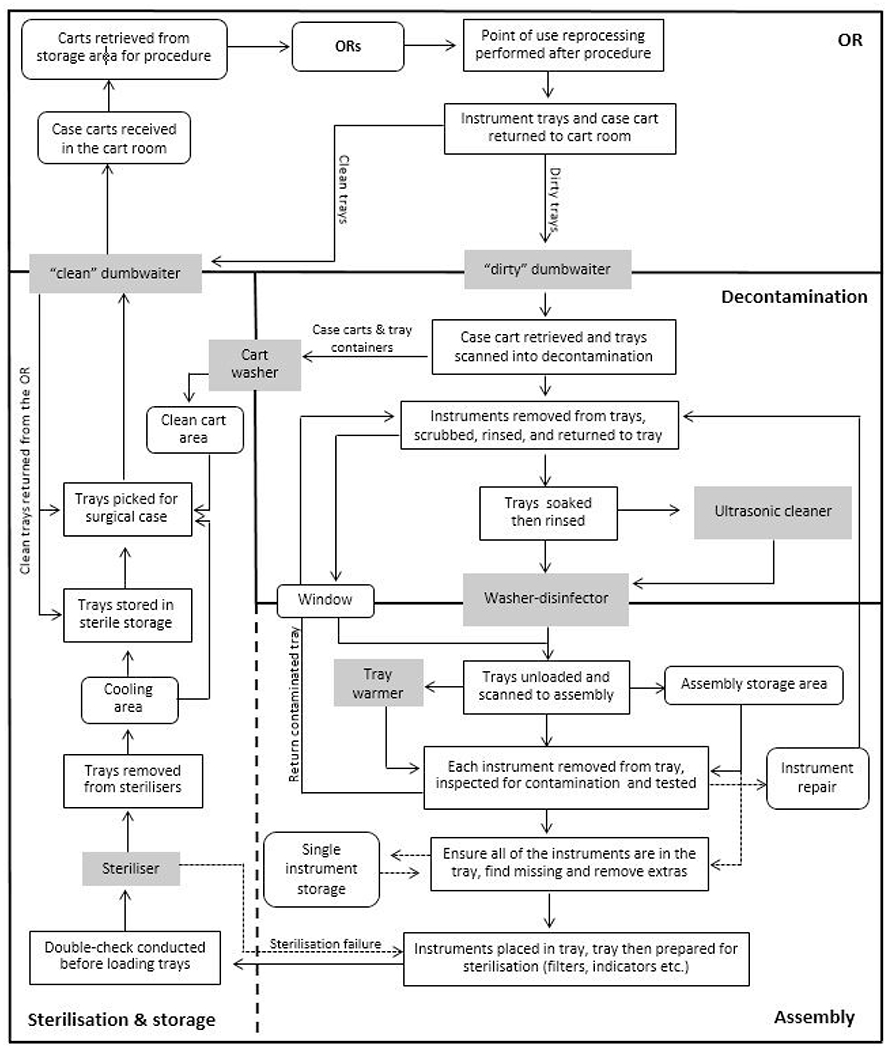

Prior to arriving in SPD, used instruments should be rinsed and reorganised in their trays at the point of use (OR, ambulatory centre or clinic). Trays are received and thoroughly cleaned in decontamination. Assembly begins when trays are transferred from decontamination via the washer disinfector or through a window that connects the decontamination room to the assembly area. Assembly is completed when the tray is staged for sterilisation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stages of instrument reprocessing. OR, operating room.

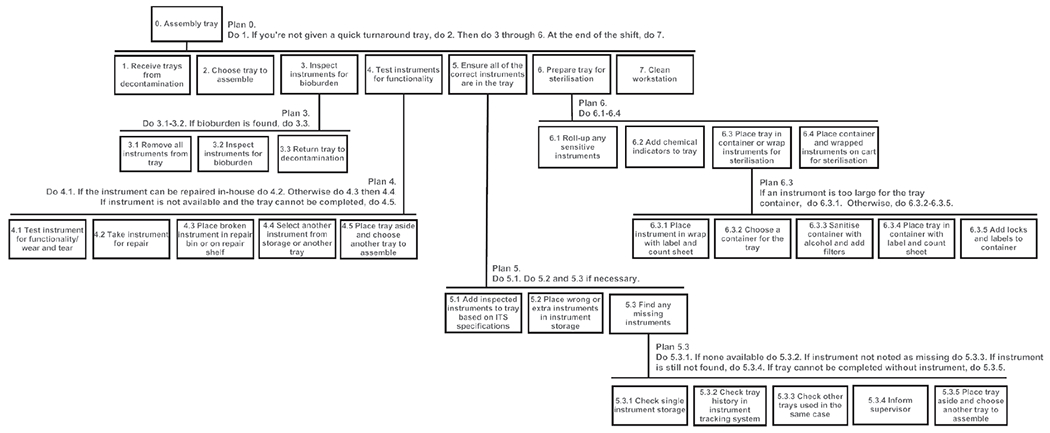

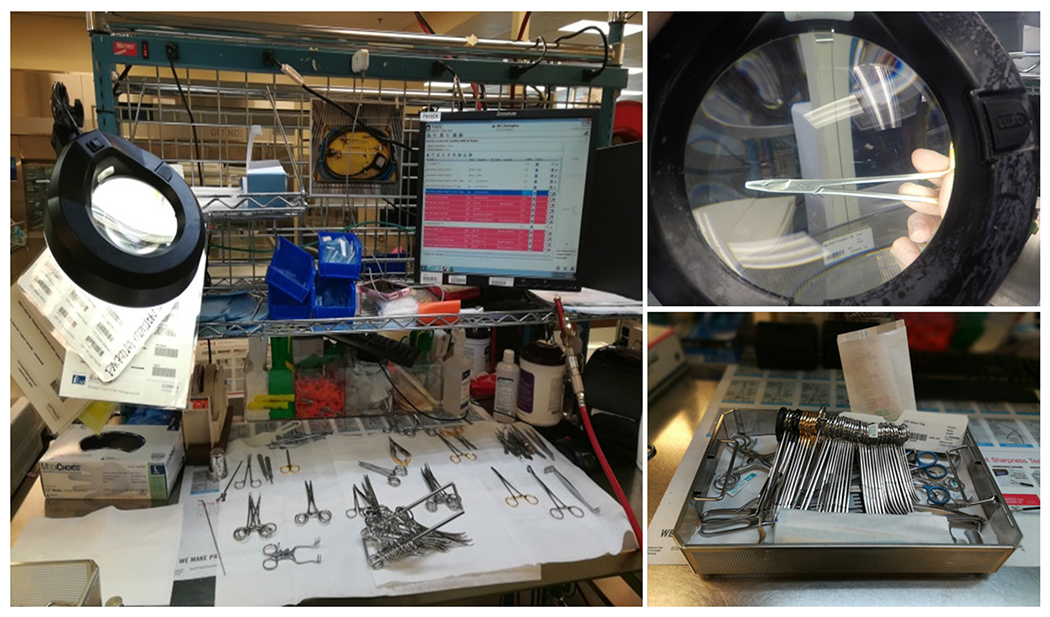

The primary tasks performed by technicians are presented in figure 2. This work is performed at the assembly workstation which includes skin cloths (used for assessing sharpness), an insulation tester (used for assessing the insulation on graspers), lubricant, a magnifier, a bar code scanner, air compressor, and a computer with the instrument tracking system (ITS), a database of the SPD instrument inventory (figure 3). This ITS is used to access the list of required instruments for each tray and provides a photo of each instrument.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical task analysis for assembly. ITS, instrument tracking system.

Figure 3.

Assembly workstation and completed tray.

Technicians choose trays to assemble based on their experience or specialty or as assigned by a supervisor. Instruments are removed from the tray and visually inspected for bioburden with a magnifier and overhead light. An air compressor is also used to inspect cannulated instruments. Trays with contaminated instruments are sent back to decontamination and logged. Instruments are tested for functionality based on the instrument check sheet, which prompts sharpness, insulation and spring action tests. Broken instruments may be repaired quickly by an instrument maintenance technician or removed from circulation. Next, the technicians ensure all of the necessary instruments are in the tray based on the specifications (number and types of instruments) listed in the ITS. Extra instruments are removed, and missing instruments are retrieved from another tray or from single instrument storage. If a missing instrument is not available the tray is either removed from circulation or a missing instrument label is added. The assembled tray is then prepared for sterilisation. Technicians may complete these tasks in different orders and may use a range of different strategies for managing tasks (eg, writing down the missing instruments and finding them after assessing the whole tray; or by finding missing instruments individually), suggesting different efficiency and thoroughness trade-offs.

Observations conducted at the three additional SPDs demonstrated assembly work at each of the three other facilities was performed comparably with differences in the technician training time, instrument tracking (instrument level vs tray level) and maintenance schedule (as needed vs per number of use).

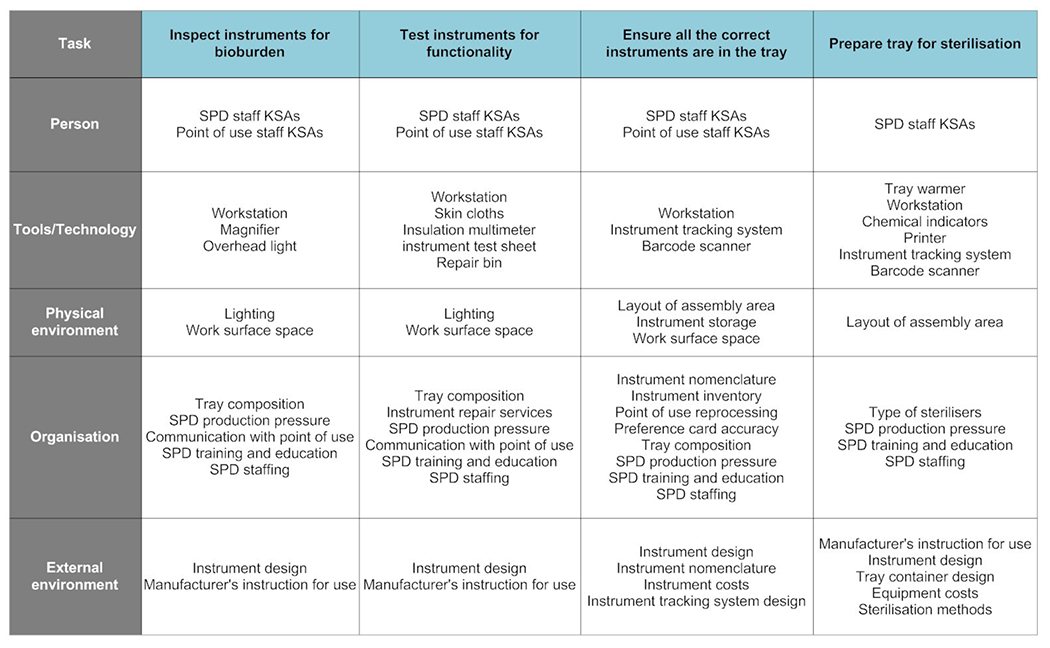

Abstraction hierarchy

The abstraction hierarchy in figure 4 illustrates the performance shaping factors that influence the key tasks of assembly work. Technician skills are critical to effective reprocessing. Technicians must prioritise trays appropriately, distinguish and choose among similarly designed instruments, understand where and how instruments hide contamination to inspect them for bioburden, determine whether instruments need repair and decide the most appropriate course of action for dealing with exceptions. This requires knowledge of surgical instruments, instrument nomenclature and departmental inventory, which in turn requires effective training, assessment and career management within the organisation to ensure technicians develop and maintain their skills. Other organisational factors include the accuracy of the list of instruments required for a surgery (‘preference cards’), variability in point-of-use reprocessing and OR production pressures. Successful performance of the assembly tasks also depends on the availability, functionality and usability of the tools and technology used in the process. These include the workstation printers, magnifier, bar code scanners, inspection tools and ITS. Internal environmental factors include space, layout, instrument storage and lighting. For example, poor storage practices create extra time pressure as technicians spend time searching for missing or replacement instruments. Externally, factors such as instrument design, manufacturer’s instructions for use and equipment costs also influence the efficiency of the assembly process.

Figure 4.

Assembly abstraction hierarchy. KSAs, knowledge, skills and attitudes; SPD, sterile processing department.

Variance matrix

The assembly process was separated into the critical tasks identified in the task analysis: inspect instruments for bioburden; check instrument functionality; ensure all the correct instruments are in the tray; and prepare tray for sterilisation. Three tasks—receiving trays from decontamination, choosing tray and cleaning workstation—were not included in the variance matrix as they did not appear to be specifically associated with tray defects.

Failures in instrument inspection include omitting the inspection, missing an instrument during the inspection or failing to identify contamination. Limited workstation space, exacerbated by trays with a large number of instruments, can create opportunities for mixing inspected and uninspected instruments. Production demands can work against thorough and systematic inspection, but are set against the technician’s knowledge and experience that can guide them to instruments and features that are prone to contamination.

Inappropriate or missed functionality tests can result in broken instruments arriving in the OR. The tests prescribed by instrument management services—sharpness, insulation, spring action—help technicians identify wear and tear and determine whether instruments should be repaired on-site or removed from circulation. Damaged instruments may also be tagged in the OR but this process was not standardised across specialties. Again, production pressures can reduce available inspection time, while a skilled technician with an understanding of how instruments are used, and thus their critical functionality, may be more efficient.

Completing the tray was the task with the most observed individual variation, with potential for either instrument omission or incorrect substitution and with processes reflecting trade-offs between risk and efficiency. Some technicians were slow and methodical, checking each instrument off the list as it is added to the tray, while others were faster, adding all instruments to the tray then checking them off on the list at the end. Incorrectly stored single instruments, varying instrument names and missing or incorrect pictures in the ITS can also contribute to failures.

Preparation for sterilisation follows a series of steps, with omissions most likely. Failures to add count sheets, chemical indicators, filters, locks and labels affect assurance procedures in the OR, usually requiring a replacement tray, leading to delays (or cancellation if a replacement is not available). Initially, this process relied on memory but an updated ITS provided a checklist. Placing trays on the incorrect sterilisation cart (eg, steam instead of low-t emperature hydrogen peroxide gas) is a less common error which could lead to ineffective sterilisation or damaged equipment.

The tasks, potential failure modes and variances for the four critical tasks are summarised in table 1. In total, we identified 17 failure modes and 20 different performance shaping factors. The primary factors were related to SPD staff KSAs, instruments (storage, nomenclature, inventory, instructions for use and design) and trays (composition, labelling and containers). Point-of-use reprocessing, ITS (design and database) and the workstation were also performance shaping factors.

Table 1.

Variance matrix of assembly critical tasks

| Task | Performance shaping factors (SEIPS classification) | Failure | Example of task variability | Process variance | Outcome variance | Observed controls (SEIPS classification) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inspect instruments for bioburden | SPD staff KSAs (person) Tray composition (organisation) SPD production pressure (organisation) ITS (tools/technology) Workstation (tools/technology) | Missed check | Tray contains 50+ instruments and with limited space on their work surface technician inadvertently mixes inspected and uninspected instruments, failing to inspect one or more instruments. | Undetected bioburden | Surgical site infection Tray defect (bioburden) New tray required OR delay Increased surgical duration Surgical deviation |

▶ Remedial/specialty training (person) ▶ In-service training (organisation) ▶ Point-of-use observations for SPD (organisation) |

| SPD staff KSAs (person) Instrument design (external) Lighting (physical environment) | Failed inspection | Technician inspects instrument but fails to identify bioburden hidden in instrument crevice. | ||||

| Test instruments for functionality | SPD staff KSAs (person) Tray composition (organisation) Instrument design (external) SPD production pressure (organisation) Communication with point of use (organisation) |

Missed check | OR did not inform SPD of issue with instrument, technician fails to test instrument as it has never been an issue previously. | Broken instrument in tray | Patient injury (burn, tear, retained object, and so on) Tray defect (non-functioning instrument) OR delay Increased surgical duration Surgical deviation New tray |

▶ Remedial/specialty training (person) ▶ ITS prompt (tools/technology) ▶ In-service training request (organisation) ▶ Point-of-use observations for SPD (organisation) |

| SPD staff KSAs (person) Communication with point of use (organisation) Instructions for use (external) Workstation (tools/technology) |

Inappropriate or ineffective check | Technician provided with little to no knowledge of how instrument is used so test is conducted in cursory manner. | ||||

| Ensure all of the correct instruments are in the tray | SPD staff KSAs (person) Instrument nomenclature (organisation/external) Instrument inventory (organisation) Instrument storage (physical environment/organisation) ITS design (external) Workstation (tools/technology) Point-of-use reprocessing (organisation) |

Wrong instrument selected | The ITS places instrument details at the end of the instrument name (eg, haemostat forceps, 14 cm, curved, satin). Technician misses appended details and chooses incorrect size and finish for the instrument. | Wrong instrument added to tray | Tray defect (wrong instrument) OR delay Increased surgical duration Surgical deviation New tray required |

▶ Remedial/specialty training (person) ▶ Assign technician to point-of-use area to assist with reprocessing (organisation) ▶ Standardised nomenclature (organisation) ▶ Tray auditing (organisation) ▶ Tray standardisation (organisation) ▶ OR staff training in SPD |

| ITS database (organisation/external) | No image, incorrect image or poor quality image in ITS | Image missing in the ITS database so the technician performs an online search and chooses the instrument based on the search results. | ||||

| ITS database (organisation/external) Preference cards (organisation) | Incorrect tray specifications in ITS | The ITS database was not promptly updated according to the revised preference cards. | Tray missing instrument(s) | Tray defect (wrong instrument) OR delay | ||

| ITS database (organisation/external) ITS design (external) SPD staff KSAs (person) SPD production pressure (organisation) | Failed to add instrument to tray | Technician counts instruments then adds them all to tray, instead of marking instruments individually in the ITS as they are added to tray, to save time. | Increased surgical duration Surgical deviation New tray required | |||

| SPD staff KSAs (person) Instrument nomenclature (organisation/external) Instrument inventory (organisation) Instrument storage (physical environment/organisation) Point-of-use reprocessing (organisation) Layout (physical environment) |

Difficulty locating instrument in assembly storage areas | Instruments not returned to correct tray during point-of-use reprocessing. Technician has to identify all trays used during the case then find and check each tray for the missing instrument. | Prolonged assembly | Reduced throughput | ||

| ITS database (organisation/external) | No image or poor quality image in ITS | Technician asks supervisor or more experienced technician to help identify the correct instrument. | ||||

| Prepare tray for sterilisation | SPD staff KSAs (person) SPD production pressure (organisation) Tray container design (external) | Failure to add count sheet | Technician rushing to add high-priority tray to the steam sterilisation load and forgets to add count sheet, indicators, locks, filters or tray labels. | No count sheet in tray | OR delay Tray defect (missing count sheet) | ▶ Remedial training (person) ▶ Sterilisation checklist (tools/technology) ▶ Dedicated workstation for sterilisation methods (physical environment) ▶ Double-check procedure (organisation) |

| Failure to add chemical indicators to the tray | Sterilisation not verifiable | OR delay Tray defect (missing indicator, filter, locks or label) New tray required | ||||

| Failure to add locks to container | ||||||

| Failure to add filters to the container | Filters missing from tray containers | |||||

| Failure to add tray labels to the container | Inability to verify tray | |||||

| SPD staff KSAs (person) Sterilisation methods (external) Tray label (organisation) Instructions for use (external) Layout (physical environment) |

Tray placed on wrong sterilisation cart | New instrument(s) added to tray but sterilisation method not updated in the ITS. Technician prints label from the ITS and adds tray to sterilisation cart listed on the label. | Wrong sterilisation method | Instrument damage Inventory costs Ineffective sterilisation Surgical site infection |

||

ITS, instrument tracking system; KSAs, knowledge, skills and abilities; OR, operating room; SEIPS, Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety; SPD, sterile processing department.

Observed controls

Improvement across the four key assembly tasks was focused on identifying the individual SPD technician who assembled the defective tray and providing remedial training (‘blame and retrain’). Manufacturer in-service training was used with clusters of defects by multiple technicians. To support inspection and functionality tests technicians were also provided opportunities to observe instrument use in the OR. OR staff were also given shifts in SPD to help understand the relationships between SPD and OR. Depending on SPD staffing level, a technician was sometimes assigned to the OR to assist with point-of-use reprocessing. Tray auditing and standardising content across providers in the same specialty aimed to reduce unnecessary reprocessing. There were efforts to standardise instrument nomenclature to avoid confusion with SPD, and to include instrument aliases in the ITS. A checklist and double-check procedure were used to ensure trays were correctly prepared for sterilisation. The ITS also issued a prompt recommending maintenance after a specific number of instrument uses. A streamlining process was also implemented to ensure all low-temperature sterilisation trays flowed to a different workstation than trays sterilised with steam.

Performance data

A total of 3900 defects were recorded in 41 799 cases, suggesting 9.3% of cases had at least one defective tray. The majority of defects, 55.0% (2158), occurred during assembly (figure 5). Of the assembly defects, 17.6% of the total defects (700) were missing instruments, and 10.9% (435) were broken, damaged or malfunctioning instruments, 8.5% (338) were the wrong instruments and 7.1% (281) of the instruments were assembled incorrectly. Other defects included missing or compromised filters (for sterility), 6.4% (253), and 4.5% (97) had an additional instrument(s) in the tray.

Figure 5.

Tray defects by reprocessing stage.

Generalisability

The failure modes, process and outcome variances faced by the other SPDs visited were similar. Each facility experienced failures such as incorrect or omitted instruments leading to process variances such as prolonged assembly and incomplete trays, and outcome variances such as delays and missing instrument defects. The performance shaping factors were present at each site but varied in degree. For example, nomenclature was likely less of an issue at one site which had previously worked to standardise nomenclature during orientation and training, in the department and in the ITS. Communication with the OR, production pressures and high staff turnover (which impacts KSAs) were specific factors in common among the sites. Noted differences included variations in technician training time (ranging from 3 to 12 months), instrument tracking (instrument level vs tray level) and maintenance schedule (as needed vs per number of use).

DISCUSSION

Our WSA related key performance outcomes to multiple sources of process variation and multiple system-level factors, demonstrating that a focus on individual performance alone (‘blame and retrain’) is limited. About 5% of cases are affected by an assembly failure, which may not, in general, cause an infection or safety risk, but can lead to significant quality and cost issues resulting from the OR delays, cancellations, additional treatments and lost and damaged instruments.2,7 Assembly requires experienced staff to maintain production while adapting to a range of potential exceptions—missing, broken and contaminated instruments—as they compensate for other systemic weaknesses such as instrument designs that hinder reprocessing, limited inventory, mixed-up tray contents and potentially unreliable processes, tools and technologies. The WSA identified multiple process variations that create these failures, each of which could be measured and addressed independently to improve overall performance. Such variances are rarely measured, let alone used to understand the system of work. However, the themes that most frequently appear in our variance matrix seemed to coalesce around the importance of skilled SPD staff, effective point-of-use reprocessing, ITS design and maintenance, instrument nomenclature and tray composition.

SPD work is highly skilled. Experienced staff perform more effective inspections (as they know where to look for bioburden) and functionality assessments (as they know how the instruments are used); deal with exceptions faster (as they know what should go in which tray, and where to find replacements); organise their work more efficiently by balancing task demands; and provide a range of other benefits such as supporting inexperienced staff. Training typically lasts 3–6 months, with a week of orientation followed by several months of on-the-job training with a preceptor, periodic formal education and ongoing ‘in service’ training.37 Cross-training of SPD technicians and OR staff was viewed favourably by SPD and OR leadership since effective point-of-use processing by OR staff with sufficient skill, motivation and resources, combined with tray auditing and feedback,38–40 may reduce assembly time, sharp risks and instrument defects.2,13,41 Conversely, reductions in preceptor availability and training time for both SPD and OR staff (eg, through financial cuts or staff turnover) can have multiplicative deleterious effects on assembly performance. Subsequent to our main period of data collection, we anecdotally observed periods of high backlog and increasingly frequent defects within our study SPDs, which appear aligned with times of high staff turnover, and a reduction in training, for both OR and SPD staff.

Well-designed ITS systems can facilitate the maintenance of the database and identification of defects. Inexperienced technicians, in particular, rely on both the image and description in the ITS. However, descriptions and photo details were not always easily visible on the assembly workstation displays, while a single instrument may be called by several different names42 (eg, ‘hemostat’ may also be called a ‘snap’, a ‘crile’ or ‘stat’), while the same instrument may differ based only on its finish (eg, polished, satin or ebony) or length (4 mm vs 5 mm). They can also be named variously by function (eg, clamp), visual descriptor (eg, scissors), a scientific name (eg, speculum) or the inventor (eg, Cooley retractor), and may change by region (eg, alligator or crocodile forceps).42–44 Maintenance of the ITS database is the responsibility of specialised SPD staff, with incorrect instrument data or images tracked and communicated to them by technicians. By association, our WSA suggests that investing in the maintenance of preference cards, pick sheets, aligning instrument nomenclature, the ITS database and the workstation displays might enhance performance.41,45,46

Optimising tray composition increases the lifespan of instruments, and reduces tray defects, inventory costs and assembly time. This requires a trade-off between creating a larger number of smaller trays for specific purposes or a smaller number of larger trays suitable for multiple procedures and surgeons. Since only 13%–51.7% of instruments in a tray may be used during a case,2,47 it is possible that unused instruments can be removed without significantly impacting a procedure. One of the SPDs observed was successful in standardising trays among one paediatric surgical specialty. Collecting data on instrument usage, engaging stakeholders and ensuring sufficient instruments for unanticipated complications,2,38,39,47,48 it is possible to reduce defects and substantially reduce cost.40,48

WSA is still a relatively new technique within healthcare that we have also applied to decontamination15 and sterilisation.29 Similar to FMEA it uses a detailed analysis of work to structure theoretical predictions about system performance and variance controls. It also shares some limitations, for example, in the ability to quantitatively explore reliability, owing to the use of mixed methods, multiple outcomes and a variety of ways to organise and present the findings. WSA enabled us to define multilevel system factors that shape behaviour, failures and outcomes, enabling a richer view of performance management than, for example, FMEA, which tends to assume linear deterministic processes, focuses on single human–system interactions. By understanding how each task is affected by multiple system components at multiple levels structured around the SEIPS model, it was possible to reveal a wider range of interventions to enhance system performance than the traditional focus on staff. Indeed, in seeking a broad understanding of the assembly process, we did not focus on specific outcomes, or the amount of variance associated with different processes (which are not usually measured), nor did we implement interventions that could have validated our findings. Instead, validity and consistency were established through our close collaboration with SPD staff over multiple iterative sessions. Our observations at the three additional reprocessing facilities, while limited by our project constraints, also supported the generalisability of our findings regarding the performance shaping factors, failures and outcomes. We did not collect tray defect data from the external sites. A larger multisite study might reveal additional nuances, and allow validation and refinement of our WSA through more quantitative focus and the study of specific interventions or configurations across different SPDs.

Our WSA revealed multilevel sociotechnical performance shaping factors in assembly that spanned organisational boundaries and resulted in variations in internal SPD processes and external outcomes. Understanding how each task is affected by multiple system components at various levels, it was possible to reveal a wider range of interventions to enhance system performance beyond the hospital’s traditional focus on individual staff behaviours and motivations. Supporting patient safety, reducing OR delays and tray defects and preventing surgical deviations would benefit from an organisational approach to the training, retention and development of skilled OR and SPD staff; a well-designed and maintained ITS; standardised instrument nomenclature; and attention to tray composition and collaboration between ORs and SPD. This analysis can provide administrators, clinicians and staff with the ability to understand the relationship between system components, generate and prioritise interventions, then predict benefits, side effects and barriers to implementation.30

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number: 1R03-HS025538-01).

Footnotes

Twitter Ken Catchpole @KenCatchpole

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data are available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Reprocessing semicritical items: current issues and new technologies. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:e53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockert EW, Langerman A. Assessing the magnitude and costs of intraoperative inefficiencies attributable to surgical instrument trays. J Am Coll Surg 2014;219:646–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dancer SJ, Stewart M, Coulombe C, et al. Surgical site infections linked to contaminated surgical instruments. J Hosp Infect 2012;81:231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seavey R High-Level disinfection, sterilization, and antisepsis: current issues in reprocessing medical and surgical instruments. Am J Infect Control 2013;41:S111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Monitoring and improving the effectiveness of surface cleaning and disinfection. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:e69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macario A What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth 2010;22:233–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson SC. Shifting the sterile processing department paradigm: a mandate for change. Aorn J 2008;88:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferschl MB, Tung A, Sweitzer B, et al. Preoperative clinic visits reduce operating room cancellations and delays. Anesthesiology 2005;103:855–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutzler L, Kraemer K, Iaboni L, et al. What do you mean you can’t sterilize it? The reusable medical device matrix. Can Oper Room Nurs J 2014;28:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catchpole K, Perkins C, Bresee C, et al. Safety, efficiency and learning curves in robotic surgery: a human factors analysis. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3749–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dexter F, Marcon E, Epstein RH, et al. Validation of statistical methods to compare cancellation rates on the day of surgery. Anesth Analg 2005;101:465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong J, Khu KJ, Kaderali Z, et al. Delays in the operating room: signs of an imperfect system. Can J Surg 2010;53:189–95 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20507792 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balch W On the brink: 3 dangers of inadequate surgical instrument reprocessing departments. Clinical Leadership & Infection Control. Available: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/quality/on-the-brink-3-dangers-of-inadequate-surgical-instrument-reprocessing-departments.html [Accessed 27 May 2020].

- 14.Seavey R Taking the chaos out of accreditation surveys in sterile processing: high-level disinfection, sterilization, and antisepsis. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:e35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfred M, Catchpole K, Huffer E, et al. Work systems analysis of sterile processing: decontamination. BMJ Qual Saf 2020;29:320–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food & Drug Administration.. Reprocessing medical devices in health care settings: validation methods and labeling, 2015. Available: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm253010.pdf [Accessed 29 May 2018].

- 17.Jolly JD, Hildebrand EA, Branaghan RJ. Better Instructions for use to improve reusable medical equipment (RME) sterility. Hum Factors 2013;55:397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi J, Seraphina S, Knudsen K. The clean and dirty of redesigning reprocessing Instructions for use. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care 2017;6:150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephens A, Assang A. What do you mean you can’t sterilize it? The reusable medical device matrix. Can Oper Room Nurs J 2010;28:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carayon P, Karsh B- T, Gurses AP, et al. Macroergonomics in healthcare quality and patient safety. Rev Hum Factors Ergon 2013;8:4–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekker S The field guide to human error investigations. Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reason J Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Routledge, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleiner BM. Macroegonomics: work system analysis and design. Hum Factors 2008;50:461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Rivera AJ, Fortier CR, et al. A human factors engineering study of the medication delivery process during an anesthetic. Anesthesiology 2016;124:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall-Andersen LB, Broberg O. Integrating Ergonomics into engineering design: the role of objects. Appl Ergon 2014;45:647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanke E, Zellmer C, Van Hoof S, et al. Understanding the current state of infection prevention to prevent Clostridium difficile infection: a human factors and systems engineering approach. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallock ML, Alper SJ, Karsh B, et al. A macro-ergonomic work system analysis of the diagnostic testing process in an outpatient health care facility for process improvement and patient safety. Taylor Fr 2007;49:544–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfred M, Catchpole K, Huffer E, et al. A work systems analysis of sterile processing: sterilization and case CART preparation. Adv Health CareManag 2019;18:173–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karsh B, Alper S. Work system analysis: the key to understanding health care systems, 2005. Available: http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA434179 [Accessed July 20, 2018]. [PubMed]

- 31.Karsh B- T, Waterson P, Holden RJ. Crossing levels in systems ergonomics: a framework to support ‘mesoergonomic’ inquiry. Appl Ergon 2014;45:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catchpole K, Neyens DM, Abernathy J, et al. Framework for direct observation of performance and safety in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:1015–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phipps DL, Meakin GH, Beatty PCW Extending hierarchical task analysis to identify cognitive demands and information design requirements. Appl Ergon 2011;42:741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colligan L, Anderson JE, Potts HWW, et al. Does the process MAP influence the outcome of quality improvement work? A comparison of a sequential flow diagram and a hierarchical task analysis diagram. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterson P, Jenkins DP, Salmon PM, et al. ‘Remixing Rasmussen’: the evolution of Accimaps within systemic accident analysis. Appl Ergon 2017;59:483–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim RHM, Anderson JE, Buckle PW. Work domain analysis for understanding medication safety in care homes in England: an exploratory study. Ergonomics 2016;59:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chobin N The real costs of surgical instrument training in sterile processing revisited. Aorn J 2010;92:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farrelly JS, Clemons C, Witkins S, et al. Surgical TraY optimization as a simple means to decrease perioperative costs. J Surg Res 2017;220:320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lunardini D, Arington R, Canacari EG, et al. Lean principles to optimize instrument utilization for spine surgery in an academic medical center: an opportunity to standardize, cut costs, and build a culture of improvement. Spine 2014;39:1714–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.John-Baptiste A, Sowerby LJ, Chin CJ, et al. Comparing surgical trays with redundant instruments with trays with reduced instruments: a cost analysis. CMAJ Open 2016;4:E404–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seavey RE. Collaboration between perioperative nurses and sterile processing department personnel. Aorn J 2010;91:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Illana Esteban E [Surgical instruments (II). An introduction to surgical instruments]. Rev Enferm 2005;28:59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips JS, Mason MJ, Dixon H. Middle ear instrument nomenclature: a taxonomic approach. BMJ 2010;341:c5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodman T, Spry C. Essentials of perioperative nursing. Vol 1. 6th edn. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeung T, Cope A, Appleton S. ’Thingamajig please, sister. you know the one I mean!’A comparison of knowledge of surgical instrument nomenclature between surgeons and theatre.. Br J Surg 2008:95. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lutfy J, Laschuk M, Seabrook C, et al. Please Pass me the umm… Tweezers”: A Needs Assessment of Resident Knowledge of Surgical Instrument Nomenclature: CCME-OG4-1. Med Educ 2014:48. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chin CJ, Sowerby LJ, John-Baptiste A, et al. Reducing otolaryngology surgical inefficiency via assessment of TraY redundancy. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;43:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farrokhi FR, Gunther M, Williams B, et al. Application of lean methodology for improved quality and efficiency in operating room instrument availability. J Healthc Qual 2015;37:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]