Abstract

Background and aims

The present study was aimed to assess the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated factors among HCWs in endoscopy centers in Italy.

Methods

All members of the Italian Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SIED) were invited to participate to a questionnaire-based survey during the first months of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy.

Results

314/1306 (24%) SIED members accounting for 201/502 (40%) endoscopic centers completed the survey. Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) were available in most centers, but filtering face-piece masks (FFP2 or FFP3) and negative pressure room were not in 10.9 and 75.1%. Training courses on PPE use were provided in 57.2% of centers only; there was at least one positive HCW in 17.4% of centers globally, 107/3308 (3.2%) HCWs were diagnosed with COVID-19 with similar rates of physicians (2.9%), nurses (3.5%) and other health operators (3.5%). Involvement in a COVID-19 care team (OR: 4.96) and the lack of training courses for PPE, (OR: 2.65) were associated with increased risk.

Conclusions

The risk of COVID-19 among endoscopy HCWs was not negligible and was associated with work in a COVID-19 care team and lack of education on proper PPE use. These data deserve attention during the subsequent waves.

Keywords: COVID-19, Endoscopy, Risk, Precautions

1. Introduction

Italy has been the first Western World Country to face a massive COVID-19 outbreak [1]. Since the end of February 2020 in few weeks the epidemic expanded rapidly from some Regions in the north of the Country, especially Lombardy, throughout the country putting the healthcare system under massive strain. Thanks to lockdown the prevalence of the disease remained much lower in the center and South of Italy [2]. At the end of March 2020, the total number of deaths at a national level was 11,951 (compared to 3264 deaths observed in China at that moment in time) with Italy suffering from the highest death toll and fatality rate worldwide [3].

The capacity of the virus to survive in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, to infect the intestinal epithelium [4,5] and its recovery in stools [6] led to the hypothesis that aerosols generated from the GI tract can transmit the infection [7]. In this view, digestive endoscopy examinations have been immediately considered high-risk procedures [8,9] due to the large viral loads in respiratory droplets, to aerosols generated by GI tract secretions including bile and stools and to the low physical distance between healthcare workers (HCWs) and patients during these procedures.

2. Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) of digestive endoscopy Units have been, therefore, considered to be at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection when getting in touch both with symptomatic COVID-19 cases and with asymptomatic virus carriers.

For these reasons, major national and international Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Scientific Societies have issued guidelines [10], [11]–12] for the correct use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and recommended significant changes of clinical practice to reduce the risk of viral spread among HCWs and patients.

Despite these consistent indications, data on the actual rate of proper use of adequate protocols and of PPE and their association with the risk of contagion in GI endoscopy Units are limited. Also, while some recent reports have suggested that GI endoscopy is relatively safe for both patients and HCWs when using adequate protective measures [13,14], data on large sets of endoscopy practice are lacking.

The primary aim of this study was to identify factors associated with the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among HCWs in Italian endoscopy centers; the secondary aim was to investigate the impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the digestive endoscopy activity in Italy.

3. Methods

3.1. Study design and participants

The present study was promoted by the Italian Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SIED). All SIED members (n = 1306), working at 502 endoscopy centers throughout the Country received an email invitation on March the 25th with follow-up invitations on April the 9th and 20th. The email was detailing the aim of the study and asking to fill-in a questionnaire regarding the activity of their Endoscopy center during the previous four weeks of the outbreak, from March 1st to 28th 2020. Participation was voluntary. A multiple choice and open-ended questionnaire including 26 items organised in five sections was developed by the coordinating center (San Raffaele Hospital, Milan) and revised and approved by the SIED scientific board committee. The full questionnaire is reported in Supplementary Table 1. Data entry was done centrally using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web application platform. No patient-personal data were collected and data about occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among HCWs were collected anonymously, thus no ethic committee request was deemed necessary.

As for the primary study outcome, we considered only confirmed COVID-19 cases, according with the WHO definition [15] as individuals with laboratory confirmation (positive RNA nasopharyngeal swab) of infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms.

3.2. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described with mean and standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables with percentages. Categorical data were analysed by Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. The agreement between participants for responses for each Endoscopy center with more than one participant was measured using the kappa (Ƙ) statistic. Values of Ƙ less than 0.40 indicate poor agreement, values between 0.41 and 0.60 moderate agreement, values between 0.61 and 0.80 good agreement and above 0.81 very good agreement [14]. If there was at least a good agreement (Ƙ > 0.60) between participants, the Endoscopy center was included in the study and data provided by the participant who completed the questionnaire first were considered. Centers with a lower agreement were excluded.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent factors associated with the risk of infection among HCWs. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the participating endoscopy centers

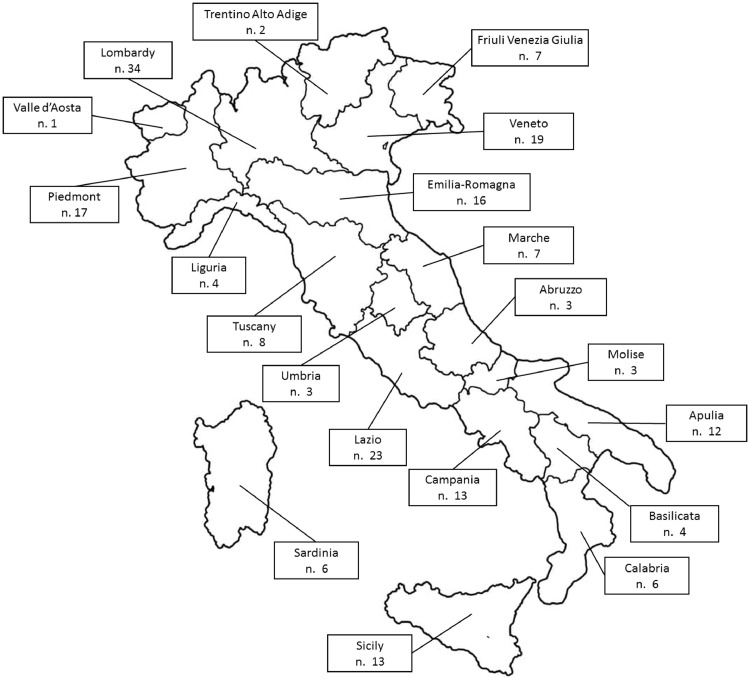

Of the 1306 invited SIED members, 314 (24% of total) (males: 221, 70.4%; mean age: 50.8 years, SD:11.1) from 201 endoscopy centers completed the questionnaire. The participation rate of endoscopy center was 40% (201/502). There was one participant for 124 (61.7%) centers and 2 to 5 participants for the remaining 77 (38.3%) centers. The agreement between participants of the same center for responses was very good (Kappa: 0.81 to 0.98) for 44 Centers and good (Kappa: 0.61 to 0.80) for 33 centers. Endoscopy centers covered all the Italian Regions (Fig. 1 ) and were equally distributed throughout the four Geographic Italian macro-areas: 56 (27.9%) were in the North West, 44 (21.9%) in the North East, 41 (20%) in the center and 60 (29.8%) in the South and Islands of Italy. Most centers (69.2%) were in community hospitals, whereas 16.4% were in University hospitals and 14.4% in private hospitals. Table 1 shows characteristics of Endoscopy centers in detail.

Fig. 1.

A map of the country showing the number of endoscopy centers participating to the present study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of endoscopy centers involved in the study.

| Endoscopy Centers, n = 201 n. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Participants per center, n | |

| 1 | 124 (61.7) |

| 2 | 54 (26.9) |

| 3 | 15 (7.5) |

| 4 | 3 (1.5) |

| 5 | 5 (2.5) |

| Geographic macro-area | |

| North-West | 56 (27.9) |

| North-East | 44 (21.9) |

| Center | 41 (20.4) |

| South and Islands | 60 (29.8) |

| Hospital setting | |

| Community hospital | 139 (69.2) |

| University hospital | 33 (16.4) |

| Private hospital | 29 (14.4) |

| Involvement of HCWs in a COVID-19 team | |

| No | 123 (61.2) |

| Yes | 78 (38.8) |

North West: Liguria, Lombardia, Piemonte, Valle d'Aosta; North East: Emilia Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Trentino Alto Adige, Veneto; Center: Lazio, Marche, Toscana, Umbria; South and Islands: Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Puglia, Sardegna, Sicilia.

4.2. Changes in endoscopy practice

None of the centers continued to perform all procedures normally. Most centers (71.6%) preserved endoscopy procedures for either inpatients or outpatients classified by the National Health System as urgent (class U) and “fast track/oncological” (class B) indication [16] while 6.5% maintained only urgent ones, without a significant difference among macro-areas. Only 4% of centers canceled all activities, 6% maintained activity only for urgent inpatients examinations, while 11.9% gave a different reply including a combination of these answers.

4.3. Use of precautions for healthcare workers

Use of surgical masks for HCWs performing endoscopy was reported by 92.5% of centers with a homogeneous distribution among macro-areas and hospital settings (Table 2 ). Notably, filtering face-piece masks (FFP2 or FFP3) were not available in 10.9% of endoscopic centers; this rate was significantly higher in the South and Islands (21.7%) than in the other macro-areas (6.4%) (p = .002). FFP2-3 masks were used for all patients in 96 (47.8%) of centers and only for those with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in 83 (41.3%) centers. Goggles or facial screen and water repellent gown were not available in 4 (2%) and 13 (6.5%) of centers, respectively. Double gloves were used when dealing with COVID-19 suspected or confirmed patients by 52 centers only (26.1%).

Table 2.

Precautions for healthcare workers in endoscopy centers stratified by geographic macroarea during the first month of COVID-19 outbreak in Italy.

| Total | Geographic macroarea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North West | North East | Center | South and Islands | |||

| Endoscopy center, n. | 201 | 56 | 44 | 41 | 60 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p value | |

| Use of surgical mask: | ||||||

| For suspected and COVID-19 patients | 4 (2) | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.3) | |

| For all patients | 186 (92.5) | 52 (92.9) | 42 (95.5) | 38 (92.7) | 54 (90) | |

| No availability of surgical masks | 11 (5.5) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (6.7) | 0.94 |

| Use of FFP2 or FFP3 masks: | ||||||

| For suspected and COVID-19 patients | 83 (41.3) | 19 (33.9) | 17 (38.6) | 21 (51.2) | 26 (43.3) | |

| For all patients | 96 (47.8) | 36 (64.3) | 22 (50) | 17 (41.5) | 21 (35) | |

| No availability of FFP2 and FFP3 | 22 (10.9) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (11.4) | 3 (7.3) | 13 (21.7) | 0.03 |

| Use of googles or facial screens: | ||||||

| For suspected and COVID-19 patients | 32 (15.9) | 5 (8.9) | 7 (15.9) | 6 (14.6) | 14 (23.3) | |

| For all patients | 165 (82.1) | 51 (91.1) | 37 (84.1) | 33 (80.5) | 44 (73.3) | |

| No availability of googles or screen | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.9) | 2 (3.3) | 0.22 |

| Use of disposable water repellent gown: | ||||||

| For suspected and COVID-19 patients | 31 (15.4) | 9 (16.1) | 4 (9.1) | 9 (22) | 9 (15.0) | |

| For all patients | 157 (78.1) | 46 (82.1) | 38 (86.4) | 29 (70.7) | 44 (73.3) | |

| No availability of disposable water repellent gown | 13 (6.5) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (7.3) | 7 (11.7) | 0.24 |

| Use of double glove*: | ||||||

| Only for COVID-19 positive patients | 10 (5.1) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (6.8) | |

| For suspected and COVID-19 patients | 62 (31.2) | 12 (21.5) | 13 (30.2) | 13 (31.7) | 24 (40.7) | |

| For all patients | 137 (68.8) | 44 (78.6) | 30 (69.8) | 28 (68.3) | 35 (59.3) | 0.41 |

| Availability of a negative pressure room | ||||||

| No | 151 (75.1) | 40 (71.4) | 28 (63.6) | 35 (85.4) | 48 (80) | |

| Yes | 50 (24.9) | 16 (28.6) | 16 (36.4) | 6 (14.6) | 12 (20) | 0.18 |

| Were training courses for dressing and undressing, including use of personal protective equipment, performed in the last 4 weeks for endoscopy staff (doctors, nurses, etc.) ? | ||||||

| No | 86 (42.8) | 20 (35.7) | 14 (31.8) | 14 (34.1) | 38 (63.3) | |

| Yes | 118 (57.2) | 36 (64.3) | 30 (68.2) | 27 (65.9) | 22 (36.7) | 0.002 |

North West: Liguria, Lombardia, Piemonte, Valle d'Aosta; North East: Emilia Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Trentino Alto Adige, Veneto; Center: Lazio, Marche, Toscana, Umbria; South and Islands: Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Puglia, Sardegna, Sicilia.

Missing data for 2 Centers: North East = 1, South and Islands = 1.

Regarding precautions in endoscopy rooms, a negative pressure was not available in 75.1% of the centers, a value equally distributed throughout the four geographic macro-areas and hospital settings. Training courses on PPE use and correct dressing/undressing procedures were provided for HCWs in only in 57.2% of endoscopy centers, with this rate being significantly lower in the South and Islands (36.7%) than in other macro-areas (North West = 64.3%, North East = 68.2% and center = 65.9%, p for trend= p.002) (Table 2). Also, this rate was lower in the academic centers (27.3%) compared to community hospitals (48.1%, p = .07) and private settings (51.7%, p=.05).

4.4. Use of precautions for patients

In 95.5% of centers, patients were interrogated about respiratory symptoms or fever occurring during the two weeks before endoscopy and in 90.1% about COVID-19 positive partners or close contacts or about having recently been in a high-risk area of the Country or abroad. Rates of answers were homogeneous among the different geographic macro-areas and hospital settings. A surgical mask was provided to patients undergoing endoscopy in 79.1% of centers. In only 8% of centers patients were recalled after 7–14 days to assess COVID-19 positivity or related symptoms.

4.5. SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care workers

The rate of Centers with at least one HCWs with a positive Sars-COV2 swab was 17.4%, with a significantly higher frequency in the North West (32.2%) than in the North East (22.7%), the center (12.2%) and the South and Islands (3.3%) (p for trend= 0.002) (Table 3 ). No differences were found after stratifying by hospital setting.

Table 3.

Occurrence of COVID-19 during the first month of outbreak amongst health care workers in endoscopy Centers stratified by geographic macroarea in Italy.

| Endoscopy center, n. | Total | North West | North East | Center | South and Islands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 201 | 56 | 44 | 41 | 60 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p value | |

| Occurrence of at least one healthcare worker (physicians, nurses, etc.) with positive COVID-19 swab in the center. | ||||||

| No | 166 (82.1) | 38 (67.8) | 34 (77.2) | 36 (87.8) | 58 (96.7) | |

| Yes | 35 (17.4) | 18 (32.2) | 10 (22.7) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0.002 |

| Occurrence of at least one physician with positive COVID-19 swab in the center. | ||||||

| 0 | 177 (88.1) | 44 (78.6) | 37 (84.1) | 37 (90.2) | 59 (98.3) | |

| 1–4 | 24 (11.9) | 12 (21.4) | 7 (15.9) | 4 (9.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.01 |

| Occurrence of at least one nurse with positive COVID-19 swab in the center.* | ||||||

| 0 | 170 (85) | 38 (67.9) | 38 (86.4) | 36 (90) | 58 (96.7) | |

| 1–4 | 30 (15) | 18 (32.2) | 6 (13.6) | 4 (10) | 2 (3.3) | 0.001 |

| Occurrence of at least one other health operator with positive COVID-19 swab in the center. | ||||||

| 0 | 191 (95) | 51 (91.1) | 42 (95.4) | 40 (97.6) | 58 (96.7) | |

| 1–4 | 10 (5) | 5 (8.9) | 2 (4.6) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.3) | 0.43 |

| In case of contact with a COVID-19 positive HCW did healthcare professionals or patients undergo COVID-19 swab screening?# | ||||||

| No | 89 (46.1) | 34 (61.8) | 13(32.5) | 21 (51.2) | 21 (36.8) | |

| Yes | 71 (36.8) | 13 (23.6) | 19 (47.5) | 15 (36.6) | 24 (42.1) | |

| Only in those operators with | ||||||

| suspected COVID-19 symptoms | 33 (17.1) | 8 (14.6) | 8 (20) | 5 (12.2) | 12 (21.1) | 0.07 |

Missing data for 1 center in the total and in the Center macroarea.

Missing data from 8 centers: North West = 1, North East = 4, South and Islands = 3. HCW = health care worker.

The rates of centers with at least one positive physician, nurse or other health operator were 11.9%, 15% and 5%, respectively. Rates of positive physicians and nurses were significantly different among macro-areas with the highest values in the North West (at least 1 physician in 21.4% and at least 1 nurse in 32.2% of endoscopic centers) and the lowest in the South and Islands (at least 1 physician in 1.7%, at least 1 nurse in 3.3% of endoscopic centers) (p = .01 for physicians and p = .001 for nurses) (Table 3).

Notably, only in 53.9% of endoscopy centers, HCWs who had been in direct contact with another suspected or positive COVID-19 HCWs underwent a swab screening.

Factors associated with the presence of at least one positive HCW in the endoscopy centers are shown in Table 4 . Involvement of HCWs in a COVID-19 care team (OR; 95% CI: 4.96; 1.97–12.51) and lack of training courses for dressing and undressing (OR; 95% CI: 2.65; 1.07–6.53) were the only factors associated with an increased risk of contagion at the logistic regression analysis.

Table 4.

Factors associated with occurrence of at least one Sars-COV-2 positive healthcare worker during the first month of outbreak in 180 endoscopy centers in Italy*.

| Centers with positive healthcare workers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Investigated factors | Non = 145 | yesn = 35 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Geographic macro-area | |||

| North-West | 34 (23.5) | 18 (51.4) | 1.0 |

| North-East | 28 (19.3) | 10 (28.6) | 0.95 (0.34–2.65) |

| Center | 34 (23.5) | 5 (14.3) | 0.51 (0.15–1.72) |

| South and Islands | 49 (33.8) | 2 (5.7) | 0.13 (0.25–0.63) |

| Practice setting | |||

| Community hospital | 103 (71) | 25 (71.4) | 1.0 |

| University hospital | 21 (14.5) | 7 (20) | 1.18 (0.40–3.51) |

| Private clinic | 21 (14.5) | 3 (8.6) | 0.54 (0.13–2.21) |

| Involvement of HCWs in a COVID-19 team | |||

| No | 99 (68.3) | 9 (25.7) | 1.0 |

| Yes | 46 (31.7) | 26 (74.3) | 4.96 (1.97–12.51) |

| Availability of a negative pressure room | |||

| No | 111 (76.6) | 23 (65.7) | 1.0 |

| Yes | 34 (23.5) | 12 (34.3) | 1.40 (0.54–3.63) |

| Training courses for dressing and undressing PPEs | |||

| Yes | 88 (60.7) | 19 (54.3) | 1.0 |

| No | 57 (39.3) | 16 (45.7) | 2.65 (1.07–6.53) |

| Use of FFP2 or FFP3 masks for all patients | |||

| Yes | 67 (46.2) | 24 (68.6) | 1.0 |

| No | 78 (53.8) | 11 (31.4) | 0.52 (0.21–1.30) |

21 centers are not included in the present analysis as some data were missing.

Globally, 107 of 3308 (3.2%) HCWs working at the participating centers were reported to have been diagnosed with COVID-19 during the first month of the pandemic. This rate was similar for physicians (35/1223, 2.9%), nurses (57/1643, 3.5%) and other health operators (15/442, 3.5%).

However, the rate of both physicians and nurses with positive swab was significantly higher in the North West of the Country, while this was not the case for the other health operators (see Supplementary Table 2).

5. Discussion

While all medical activities are currently at an increased risk of COVID-19 spread, GI endoscopy is considered to carry one of the highest. This is the largest survey reporting nationwide data on the risk of contagion among HCWs in endoscopy units and associated factors. Data on changes in the organisation of the units and on employed precautions were also recorded. The study involved 201 centers homogeneously distributed throughout Italy, during the first month of the outbreak, with different types of hospital settings.

Most centers tried to fulfill recommendations to protect both patients and endoscopy staff against the risk of contagion [10–12]. However, some precautions were less frequently employed, especially in Areas of the Country with a lower viral spread. Notably, although in most cases endoscopy staff regularly received adequate PPEs, training courses on their proper use and on dressing and undressing were only delivered in about half of the centers in Italy and in one third of centers of the South and Islands macro-area. The lack of training courses on the use of PPEs and the involvement of HCWs in a COVID-19 team were associated with an increased risk of infection at the logistic regression analysis.

As for other PPEs, the availability of goggles or facial screens, water repellent gowns and the use of FFP2 or FFP3 masks was suboptimal, in particular in the South and Islands, with minimal use of double gloves in COVID-19 suspected or positive patients. However, these factors were not associated with the risk of infection. Finally, there was a very low recall rate to check about COVID-19 positivity or related symptoms occurring after the endoscopic procedures, and HCWs who came in touch with suspected or positive COVID-19 colleagues underwent a screening swab in only some 50% of centers.

The present study has some strengths, such as the nationwide coverage with 201 Italian centers, evenly distributed across the Country, representing almost half of all digestive endoscopy Units in the Country, and the attempt to investigate factors associated with the risk of confirmed COVID-19 positivity among HCWs.

A previous study conducted in only 42 centers in the North-West of Italy [17] reported a similar rate of infection in this high-risk area, but the rest of the Country was not included.

Indeed, the present study shows that the spread of COVID-19 infection among HCWs gradually decreased in the North East, the center and the South of the Country mirroring the prevalence of the infection in the general population (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Globally, 3.2% of HCWs working at the participating endoscopy centers in Italy were diagnosed with COVID-19 with a nasopharyngeal swab. Most likely, many other HCWs were infected and remained asymptomatic, as there was no general screening. Also, the rate of infected physicians and nurses seemed to be more strictly associated with the different Areas of the Country, while this was not the case for other HCWs such as intermediate care technicians performing surface disinfection, patient transport and scope reprocessing. This may suggest that a direct involvement in endoscopic procedures increases the risk of contagion. Similar data were recently reported in a survey limited to Lombardy endoscopy centers [18]. Another explanation for this finding may be that physicians and nurses had more chances to receive swabs.

As for the analysis of factors associated with the occurrence of COVID-19 among HCWs, notably, only the involvement of HCWs in a “COVID-19 team” and the lack of a specific training on the use of PPE including correct dressing and undressing were associated with an increased risk. This result is novel but not surprising, as a recent Cochrane review [19] underlined how doffing PPE properly is one of the most important factors to reduce infectious disease risk among HCWs. The finding that this kind of courses were significantly less likely to be available in academic centers, although often available online [20], is a matter of concern, given their importance for students and residents, and deserves further investigation. The reasons for the statistical significance of this variable, but not of the use of PP2/PP3 masks in all cases, may be due to the fact that only 22 centers (10%) did not have PP2/PP3 available (Table 2), thus our analysis may result underpowered. Also, the rate of Centers without availability of PP2/PP3 masks was much higher in the south of the Country (21.7%) where the infection was far less prevalent during the first wave.

Apart from the precautions and the infection risk, the study confirms a clear reduction of endoscopic activities at a National level as the vast majority of the Centers limited the activity to urgent or “fast-track” procedures. This is in keeping with recent data from the UK [21] and France [22] and raises the issue of the possible risk of delay of significant medical conditions. These data and others on the rate of patients not-presenting to the hospitals despite booked “fast-track” procedures [16] should, therefore, be carefully considered during the phases of recovery from the outbreak that may become cyclical [23].

The study also carries several limitations. The participation rate of individual endoscopists was relatively low (25%), but almost half (40%) of endoscopic centers throughout Italy were included in the survey. Also, due to time constraints, in case of discrepancies between endoscopists of the same center, we chose not to send a further query to solve minor disagreements. This pragmatic choice may have limited precision, but it is unlikely to have hampered the results.

The data on the occurrence of infection are most likely an underestimation, as many others HCWs were probably infected and did not undergo swab being asymptomatic. Also, data on severity of the disease in endoscopy HCWs, need of hospitalisation and death were that would have added further relevant information were not available for several reasons: (a) the study was conceived as a survey on practice in Endoscopy Units and factors associated with infection; (b) as the study was considered a survey with no need of IRB approval, personal details on sex, age and clinical outcome of infected individuals were not considered obtainable as the disease course of individual HCWs was considered a matter of privacy. However, it is likely that the outcome of COVID19 in the workers in the Endoscopic Centers was not substantial different from that in subjects of the general population.

Finally, the accuracy of a similar survey may be hampered by personal judgment or mistakes, but the high agreement among HCWs of the same centers is in this view reassuring.

In conclusion, this national survey shows that during the first month of the COVID-19 outbreak there was a considerable reduction of the routine endoscopy activity homogeneously in all Italian macro-areas and hospital settings. Improvements are needed to obtain a more effective rescheduling policy of the cases that have been post-poned and recall of suspected or positive COVID-19 patients. We also found that preventive measures, such as the correct sequence of putting on and taking off PPE is critical, particularly for physicians and nurses and need implementation.

Study contribution

AM, GC, PGA, RMZ conception and design; AM, RMZ analysis and interpretation of the data; AM and GC drafting of the article; AM, GC, GM, HB, SFC, AT, LP, PGA, RMZ critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and final approval of the article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding information

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dld.2021.03.014.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. Apr 11Epub 2020 Mar 13.PMID: 32178769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day M. Covid-19: Italy confirms 11 deaths as cases spread from north. BMJ. 2020;368:m757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m757. Feb 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Last accessed March 29, 2020.

- 4.Gu J., Han B., Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. Mar 3pii: S0016-5085(20)30281-X. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardinale V., Capurso G., Ianiro G. Intestinal permeability changes with bacterial translocation as key events modulating systemic host immune response to SARS-CoV-2: a working hypothesis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung K.S., Hung I.F., Chan P.P. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from the Hong Kong cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao F., Tang M., Zeng X. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. Mar 3pii: S0016-5085(20)30282-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Repici A., Maselli R., Colombo M. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. March[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain A., Singhal T., El-Hasani S. Extent of infectious SARS-CoV-2 aerosolisation as a result of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy. Br J Hosp Med. 2020;81(7):1–7. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2020.0348. (Lond).Jul 2Epub 2020 Jul 6. PMID: 32730160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gralnek I.M., Hassan C., Beilenhoff U. ESGE and ESGENA position statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and the COVID-19 pandemic. Endoscopy. 2020;52(10):891–898. doi: 10.1055/a-1213-5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sultan S., Lim J.K., Altayar O., on behalf of AGA AGA institute rapid recommendations for gastrointestinal procedures during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):739–758.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galloro G., Pisani A., Zagari R.C. Safety in digestive endoscopy procedures in the COVID era recommendations in progress of the Italian society of digestive endoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.002. May 13[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Repici A., Aragona G., Cengia G.P. Low risk of covid-19 transmission in GI endoscopy. Gut. 2020;0:1–3. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi G., Zaccari P., Apadula L. Factors associated with the risk of patients and health care workers to develop COVID-19 during digestive endoscopy in a high-incidence area. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;93(1):274–275. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus 2019?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIqIz7mMen6gIVDxsYCh3dYQ35EAAYASAAEgKYtvD_BwE. last accessed June29, 2020.

- 16.Armellini E., Repici A., Alvisi C. Fast track endoscopy study group. Analysis of patients attitude to undergo urgent endoscopic procedures during COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(7):695–699. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.015. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Repici A., Pace F., Gabbiadini R. Endoscopic units and the COVID-19 outbreak: a multi-center experience from Italy. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.003. Apr 10pii: S0016-5085(20)30466-2[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capurso G., Archibugi L., Vanella G. Infection control practices and outcomes of endoscopy units in the Lombardy region of Italy: a survey from the Italian society of digestive endoscopy during COVID-19 spread. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001440. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbeek J.H., Rajamaki B., Ijaz S. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub3. Published 2019 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelrahim M., Hossain E., Subramaniam S., Bhandari P. Essentials of donning, doffing, and changes in endoscopy practice to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 during endoscopy. VideoGIE. 2020;5(8):332–334. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.04.013. Jun 29PMID: 32821862; PMCID: PMC7323670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutter M.D., Brookes M., Lee T.J., Rogers P., Sharp L. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: a national endoscopy database analysis. Gut. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322179. Jul 20gutjnl-2020-322179Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32690602; PMCID:PMC7385747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belle A., Barret M., Bernardini D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gastrointestinal endoscopy activity in France. Endoscopy. Dec 2020;52(12):1111–1115. doi: 10.1055/a-1201-9618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manes G., Repici A., Radaelli F., Bezzio C., Colombo M., Saibeni S. Planning phase two for endoscopic units in Northern Italy after the COVID-19 lockdown: an exit strategy with a lot of critical issues and a few opportunities. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(8):823–828. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.042. AugEpub 2020 Jun 19. PMID: 32605868; PMCID: PMC7303656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.