ABSTRACT

Introduction

Lung injury has several inciting etiologies ranging from trauma (contusion and hemorrhage) to ischemia reperfusion injury. Reflective of the injury, tissue and cellular injury increases proportionally with the injury stress and is an area of potential intervention to mitigate the injury. This study aims to evaluate the therapeutic benefits of recombinant human MG53 (rhMG53) protein in porcine models of acute lung injury (ALI).

Materials and Methods

We utilized live cell imaging to monitor the movement of MG53 in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells following mechanical injury. The in vivo efficacy of rhMG53 was evaluated in a porcine model of hemorrhagic shock/contusive lung injury. Varying doses of rhMG53 (0, 0.2, or 1 mg/kg) were administered intravenously to pigs after induction of hemorrhagic shock/contusive induced ALI. Ex vivo lung perfusion system enabled assessment of the isolated porcine lung after a warm ischemic induced injury with rhMG53 supplementation in the perfusate (1 mg/mL).

Results

MG53-mediated cell membrane repair is preserved in human bronchial epithelial cells. rhMG53 mitigates lung injury in the porcine model of combined hemorrhagic shock/contusive lung injury. Ex vivo lung perfusion administration of rhMG53 reduces warm ischemia-induced injury to the isolated porcine lung.

Conclusions

MG53 is an endogenous protein that circulates in the bloodstream. Therapeutic treatment with exogenous rhMG53 may be part of a strategy to restore (partially or completely) structural morphology and/or functional lung integrity. Systemic administration of rhMG53 constitutes a potential effective therapeutic means to combat ALI.

INTRODUCTION

Acute lung injury (ALI) can result from severe trauma, infection from natural or weaponized biologic agents, radioactive substances, or hemorrhagic shock. Although the mechanisms and pathophysiology of injury progression are varied based on the injury, the common resulting ALI significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality in military service personnel.1 Specifically, ALI can occur after hemorrhagic shock and/or contusion in up to 30% to 50% of soldiers and civilians which leads to a broad area of impact. Increased microvascular permeability leads to alveolar edema, a decreased gas exchange, worsening pulmonary function, and potentially death. This dual-injury mechanism of hemorrhage and direct thoracic trauma has clinical relevance directly to the military application as well as civilian populations with polytrauma.

A therapeutic agent that is able to be delivered to the site impacted by these deleterious effects of hemorrhagic shock, for example, the small airway epithelia and the disrupted microvasculature, can potentially add restorative support to regain function of the pulmonary system would be an effective therapy to treat ALI. Our group recently identified MG53 as an essential gene for cell membrane repair. MG53 acts as a sensor of redox-change and nucleates the assembly of repair patches at acute membrane injury sites.2–7 Genetic ablation of MG53 results in defective membrane repair and tissue regeneration.4,8 MG53 knockout mice show increased susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion and over-ventilation-induced injury to the lung when compared with wild-type mice.9 In addition to the intracellular action of MG53, injury to the cell membrane exposes a signal that can be detected by circulating MG53, allowing recombinant human rhMG53 (rhMG53) protein to repair membrane damage when provided in the extracellular space.9–12 We found that intravenous (IV) delivery or inhalation of rhMG53 reduces symptoms in rodent models of ALI and emphysema. Repetitive administration of rhMG53 improves pulmonary structure associated with chronic lung injury in mice.9 These data indicated a physiological function for MG53 in the lung and suggest that targeting membrane repair can be an effective means for treatment or prevention of lung diseases. Although MG53 is innate and endogenous in mammals, a native injury response associated with large injury and ALI would overwhelm the endogenous ability of repair and thus support a notion of administration of exogenous rhMG53 as a therapeutic to mitigate ALI.

While an ideal setting of intervention would be prophylactically before the injury stimulus is delivered, that approach lack real-world applicability. Therefore, we sought to demonstrate the efficacy of exogenous rhMG53 as a potentially therapeutic treatment approach administered after the injury to restore lung function. In this study, we sought to utilize well-established porcine models of multiple trauma that included both hemorrhagic shock and pulmonary contusion, and warm ischemic injury of ALI to evaluate the potential therapeutic benefits of exogenous rhMG53 delivered to the lung with varied etiologies of ALI.13–17

METHODS

Live Cell Imaging of MG53 Translocation to Injury Sites in Bronchial Epithelial Cells

For in vitro membrane injury assay, BEAS-2B (B2B) cells, derived from human bronchial epithelium (ATCC CRL-9609, Manassas, VA), were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Transfection of GFP-MG53 into B2B cells was performed using the Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Life Technologies) per manufacturer’s instructions. B2B cells expressing GFP-MG53 were subjected to microelectrode penetration-induced acute injury to the plasma membrane as previously described.2,10

Animals

All animal experiments were performed under the approval and guidance of the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of Minnesota IACUC protocol # 1805-35872A and The Ohio State University IACUC protocol # 2012A00000126). All experiments were performed in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). For porcine experiments, adult swine were utilized from recognized approved sourcing.

Hemorrhagic Shock and Contusive Lung Injury Model of ALI Experimental Protocol

Male Yorkshire pigs weighing 15 to 25 kg were anesthetized with an intramuscular dose of telazol 4 to 6 mg/kg and orotracheally intubated. Mechanical ventilation was initiated and maintained throughout the instrumentation, injury, shock, and resuscitation phases of the experiments (Fig. 1A). PaO2 was titrated to a range of 70 to 120 mm Hg, and the PaCO2 was kept between 35 and 45 mm Hg. Anesthesia was maintained with inhaled nitrous oxide and propofol.

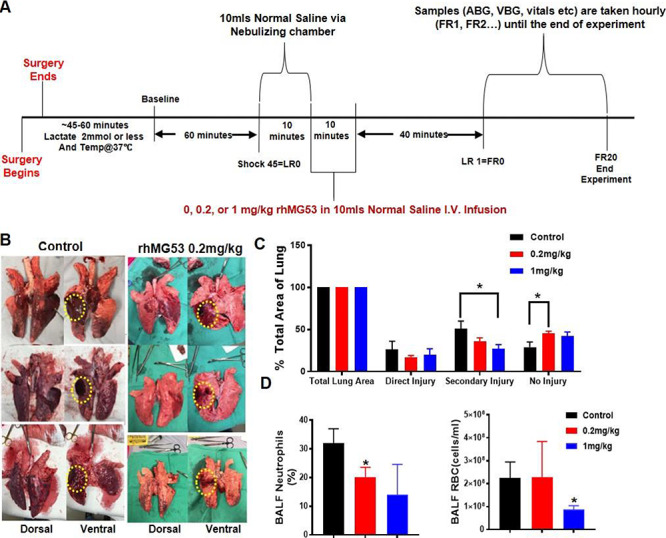

FIGURE 1.

In vivo rhMG53 protects against contusion/hemorrhagic-shock-induced acute lung injury in pigs. (A) Study protocol overview diagram of the effective IV dose ranging studies of the hemorrhagic and contusive shock combined trauma model of acute lung injury in the porcine model. (B) Representative photographs of the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the explanted lungs after the combined trauma model demonstrating the direct or focal injury area, the secondary or penumbra area, and the distant or no injury area utilized for image acquisition; (C) Quantification of lung injury from explanted lungs represented in Fig. 1B. (D) Bronchioalveolar lavage fluid samples demonstrating measured red blood cell (erythrocyte) count and percent neutrophils. Data presented in panels 1C and 1D are mean ± SEM.

Two peripheral IV catheters were placed for delivery of anesthesia and peripheral access. A central venous catheter is placed via internal jugular cut-down, and temperature is monitored continuously using central line thermistor. An arterial line is placed in the surgically exposed femoral artery. All animals are monitored with continuous ECG, pulse oximetry (SpO2), and bi-spectral index (for sedation monitoring). Animals undergo laparotomy, direct cystostomy tube placement (to accurately follow urine output), splenectomy, and cannulation of the inferior vena cava (for controlled hemorrhage).

After instrumentation, pigs are allowed to stabilize for a minimum of 1 hour or until serum lactate levels are 2.0 mmol/L or less, and the animal’s temperature was at least 37°C. At this time, baseline measurements are obtained, and the shock protocol is initiated. All animals receive a right-sided chest injury using a captive bolt gun to create a blunt percussive injury. Multiple (2 to 5) rib fractures and underlying pulmonary contusion are the typical injury pattern in our animals. Hemorrhagic shock is induced by withdrawal of blood from the inferior vena cava until a sustained systolic blood pressure (SBP) in the mid-50s (mm Hg) is reached (typically requiring removal of 35% to 50% of total blood volume). Shed blood is withdrawn into an acid citrate dextrose bag for autotransfusion during full resuscitation. The animals are allowed to remain in shock with no intervention for 45 minutes. At this time, physiologic parameters are assessed and recorded, and blood is collected for laboratory measurements.

After 45 minutes of shock, pigs receive 1 hour of limited resuscitation with a target SBP of greater than 80 mm Hg. This resuscitation is done to simulate transport time to definitive care and models clinical decisions regarding resuscitation in the field, that is, fluid administration based on palpable radial pulse, which corresponds to an approximate SBP of 80 mm Hg.13 Animals receive IV boluses of lactated Ringers (LR) solution at 20 mL/kg to maintain SBP of greater than 80 mm Hg during this limited resuscitation phase.

In order to determine the effective dosing of a therapeutic rhMG53 protein, animals were randomized and blindly received one of the three doses: sham (vehicle only), 0.2, or 1 mg/kg, given intravenously during the limited resuscitation period (to simulate arrival at emergency department). After 60 minutes of limited resuscitation, animals received IV boluses of LR solution at 20 mL/kg to maintain SBP of ≥ 90 mm Hg. If SBP was < 90 mm Hg and the animal had a lactate < 2 mmol/L and a urine output ≥ 1 cc/kg/h, then the animal would continue to be monitored. If the urine output was < 1 cc/kg/h and/or the lactate ≥ 2 mmol/L, then a 20 cc/kg LR bolus was administered.

To provide stability during the 24-hour post-injury period, 22F thoracostomy tube is inserted into the right chest and placed to − 20 cm H2O suction during the resuscitation phase. After 1 hour of limited resuscitation, full resuscitation is initiated. During full resuscitation, glucose levels are maintained with IV bolus of 25 mL of 50% dextrose for glucose levels of less than 60 mg/dL. After 24 hours of resuscitation, bronchioalveolar lavage fluid and vital signs are obtained, and the animals are euthanized with samples of tissues obtained after euthanasia.

Porcine Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion

Adult pigs were sedated, anesthetized, heparinized (300 U/kg), and then euthanized per IACUC approved protocol after intubation. After the appropriate warm ischemia/hands-off period, the sternotomy and exposure of the heart and great vessels was performed in the standard fashion.15–17 Antegrade flush of cold pulmoplegia (Perfadex, XVIVO, Goteborg Sweden) was performed. The lungs were then dissected, mobilized, and recovered after submaximal ventilation. The lungs were kept on ice until time of ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP). The tracheal, left atrial, and pulmonary artery cannulations were performed per standard protocol, and the EVLP run was initiated. The perfusion was increased until targeted cardiac output and the lungs were ventilated when 32°C was reached. Control or rhMG53 protein was administered to the perfusate. At completion of the EVLP, tissue and perfusate were collected.

Perfusate Measurement Analysis of Cytokines and Lactate Dehydrogenase

Supernatants were collected from EVLP perfusates. IL-6 (ng/mL) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was measured in perfusate using the LDH cytotoxicity detection assay kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density values were analyzed at 490 or 492 nm by subtracting the reference value at 620 nm. EVLP had four biological replicates, and assays were run in triplicate.

Histopathology

Histologic specimens were stored in 10% formalin, transferred to ethanol for paraffin embedding, and 5-μm sections were cut and processed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed using standard methods.

Statistical Analyses and Study Integrity

Unless otherwise stated, the results were expressed as means ± SD for each treatment group. The difference determined between two groups with a two-tailed Student’s t-test P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. At the time of the experiment, the research staff were provided with a vial labeled with a research study number blinded to the treatment delivered. In the post-experiment analysis and pathologic evaluation, the research associate and pathologists were blinded as well and only had the study number for reference.

RESULTS

MG53 Repairs Acute Injury to Alveolar Epithelial Cells

MG53 is a member of the TRIM family protein that is well conserved among the animal species (Fig. 2A). The amino acid sequence of MG53 from pigs is 94% identical to the human sequence.

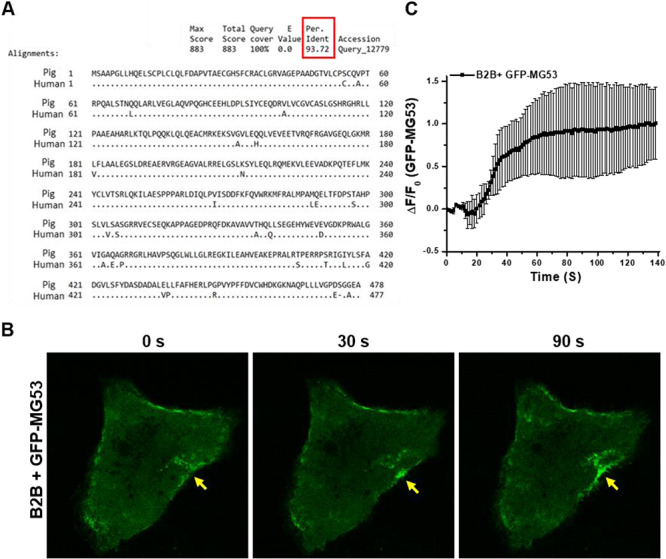

FIGURE 2.

MG53 facilitates cell membrane repair in lung epithelial cells. (A) The amino acid sequence of theMG53 protein demonstrating ~ 94% conservation between human and porcine species. (B) Micrograph of cell membrane injury in B2B cells demonstrating a time-lapse image of the recruitment of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-MG53 to the injury site. (C) Time- dependent translocation of GFP-MG53 to injury sites on B2B cells.

We used cultured B2B cells, derived from human bronchial epithelium, to investigate the extent that MG53 participates in repair of injury to lung epithelial cells. The B2B cells were transfected with a fusion protein containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) linked to the amino-terminal end of the human MG53 (GFP-MG53). At the resting state, GFP-MG53 in B2B cells localized primarily to the cytosol and plasma membrane (Fig. 2B). In response to injury caused by penetration of a microelectrode into the plasma membrane, rapid translocation of GFP-MG53-labeled intracellular vesicles toward the acute injury site was observed at different time points after injury (Fig. 2B, see Appendix 1 for live cell imaging of GFP-MG53 movement in B2B cells). The time-dependent accumulation of GFP-MG53 at the acute injury sites in B2B cells is similar to those observed in muscle and other cell types (Fig. 2C).2,10,18,19 These findings suggest that MG53-mediated membrane repair machinery is conserved in human lung epithelial cells.

rhMG53 Protects Against Combined Hemorrhagic Shock/Contusive Lung Injury in Pigs

We followed the established dual-injury model of hemorrhagic shock and contusive lung injury in the porcine model, as described in Fig. 1A.14 This model produces a focal direct injury site with a surrounding penumbra of secondary injury. The systemic effects of this combined model result in a propagation of the injury to remote lung tissues (Fig. 1B). We found that the exogenous IV administration of rhMG53 during the limited resuscitation phase led to significant reduction in the zones of injury as measured by quantified image analysis measurements of the zones of injury (Fig. 1A). The protective effect of rhMG53 is dose dependent (Fig. 1C). These significant effects on reduction in injury severity were seen at concentrations as low as 0.2 mg/kg (Fig. 1B).

The bronchioalveolar lavage fluid was collected at the end of the full resuscitation period (20 hours post resuscitation, Fig. 1A). Flow cytometric-assisted cell sorting analysis revealed reduction of the percentages of neutrophils (Fig. 1D, left) and red blood cells (Fig. 1D, right) in pigs that received rhMG53 treatment. With the limited number of animals used (n = 3, control; n = 3, 0.2 mg/kg rhMG53; n = 4, 1 mg/kg), we observed statistically significant reduction in the percentage of neutrophils with 0.2 mg/kg rhMG53 treatment group and reduction in the red blood cell count with the 1 mg/kg rhMG53 treatment group. These findings support the therapeutic benefits of rhMG53 in a treating a hemorrhagic shock/contusive lung injury model of ALI.

Ex Vivo Delivery of rhMG53 Preserves Integrity of Porcine Lung to Warm Ischemic Injury

We utilized an established EVLP system to perform normothermic perfusion of the isolated porcine lung to assess lung integrity (Fig. 3A).15–17 In this study, the isolated lung was subjected to 1 hour of warm ischemia and then rhMG53 (5 µg/mL) was supplemented to the perfusate during EVLP.

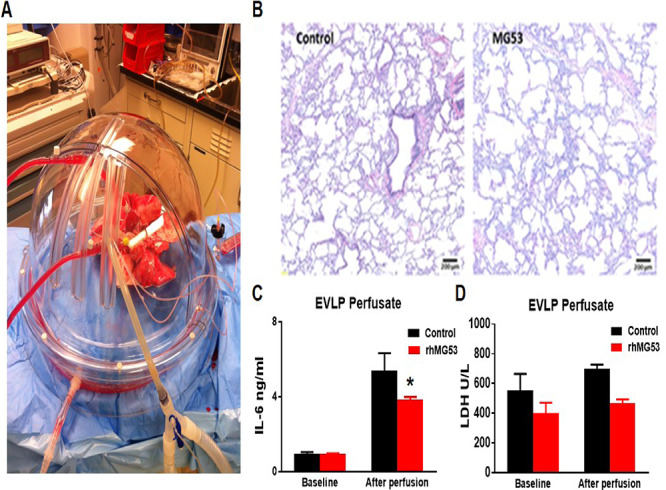

FIGURE 3.

Exogenous rhMG53 mitigates ischemic lung injury in a pig ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) system. (A) The EVLP model with porcine lungs being perfused. (B) Histologic micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung. (C) Cytokine levels of IL-6 in the control or rhMG53 drug EVLP groups. (D) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the perfusate at the completion of the EVLP in the control or rhMG53 drug groups.

As shown in Fig. 3B, hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed preservation of lung parenchymal architecture with minimal interstitial edema when the perfusate was supplemented with rhMG53. We collected the EVLP perfusate from eight pigs at the completion of the run and quantified the inflammatory cytokine concentration. Exogenous supplementation of rhMG53 resulted in mitigation of the inflammatory cytokine response (IL-6) measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Fig. 3C). In addition, rhMG53 reduced LDH in the perfusate as compared to vehicle control, demonstrating a preservation of overall lung integrity (Fig. 3D). Overall, this data demonstrate that rhMG53 has beneficial effects in preservation of porcine lung integrity in the EVLP system.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have shown that targeted membrane repair with rhMG53 may be an effective means for treatment or prevention of lung injury in rodent models.9 Data generated from this study support the therapeutic benefits of rhMG53 in treating ALI following hemorrhagic shock, contusive lung injury, and ischemic injury in porcine models.

RhMG53 protein has the potential of being a stockpilable, therapeutic agent as it can be manufactured in large scale, and the protein stored as a lyophilized powder remains stable at 4°C for greater than 2 years. We have shown that rhMG53 can be easily reconstituted into physiological saline solution for IV or inhalation administrations.9–12,18,19 Additionally, since MG53 is present at low levels in serum circulation under normal physiologic conditions, the administration of rhMG53 is not likely to produce neutralizing antibodies as peripheral tolerance to this protein has already occurred.10,12,20 Thus, we expect that rhMG53 can be a safe biological agent to treat ALI which is supported by our previous rodent study and the present studies in the larger animal pig model.9

Our previous studies have shown that systemically administered rhMG53 could recognize injury to both epithelial and endothelial layers in the lung. Moreover, aerosolized delivery of rhMG53 is effective in preservation of lung structure and function in mice subjected to ALI. Based on these findings in rodent and large animal models of ALI, we rationalize the dual delivery approach of rhMG53 (both IV and inhaled) to protect against hemorrhagic-shock-induced ALI. We envision that aerosolized administration of rhMG53 allows for convenient delivery to the small airway epithelia, whereas IV infusion would allow for rhMG53 protein to be directly available to the capillary beds affected by the trauma. As a first-line medical treatment, service personnel would have the potential ability to self-administer rhMG53 immediately after trauma via inhalation, in a fashion similar to a rescue inhaler used for asthma. Ventilator-mediated inhalation of rhMG53 can also be applied during transport of patients from the site of injury to the hospital, to preserve lung function during the early phase of trauma. When reaching the medical care station/hospital, IV infusion of rhMG53 can be coadministered with aerosolized rhMG53. Through this combined inhalation and systemic delivery of rhMG53, we can achieve an effective dual-pronged approach to treat ALI.

This study has several strengths and some limitations. We utilized two well-established large animal models of ALI, contusive/hemorrhagic shock and ischemia. These two separate models are relevant to the human condition. The models are complementary to the cell culture work and supportive of our prior small animal findings.2–4,8–12,18,21 While, indirect, we have demonstrated therapeutic potential of rhMG53 in restoring lung function post injury. Our histopathologic analysis utilized formalin fixation and paraffin embedment as previously described, though we acknowledge that there are alternative fixation strategies which may have been used which would have reduced potential for sectioning artifacts.9,13,14,16,22–24 Although we were able to demonstrate benefits of rhMG53 as a potential therapeutic, our sample size was relatively modest though given the limitations of cost and animal utilization reflective of large animal studies. The true measure of the ischemic injury protection would be a transplant or blood reperfusion model after ex vivo delivery and these more extensive studies are ongoing and in their initial stages.

These promising findings form the foundation of future drug development studies toward human application as it particularly relates to the military traumatic injury. As we have observed, ex vivo delivery of rhMG53 to the isolated lung organ has benefits in preserving and/or restoring lung integrity following warm ischemic injury; thus, another potential application of rhMG53 could be transplantation either during recovery, storage and preservation, or resuscitation. From our military relevant model of contusive injury coupled with hemorrhagic shock, we see that exogenous rhMG53 therapeutically delivered in a resuscitative phase, analogous to triage and stabilization, results in reduction in overall area of lung injury and injury markers. In aggregate, these findings would support the rationale of further developing exogenous rhMG53 as a shelf stable therapeutic agent with the potential to restore lung function and lessen the impact of ALI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to recognize the support of The Ohio State University and University of Minnesota University Laboratory Animal Resources (ULAR) to the Beilman, Ma, and COPPER laboratories.

Contributor Information

Bryan A Whitson, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; Department of Surgery, Collaboration for Organ Perfusion, Protection, Engineering and Regeneration (COPPER) Laboratory, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Kristine Mulier, Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Haichang Li, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Xinyu Zhou, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Chuanxi Cai, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Sylvester M Black, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; Department of Surgery, Collaboration for Organ Perfusion, Protection, Engineering and Regeneration (COPPER) Laboratory, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Tao Tan, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; TRIM-edicine, Inc., Columbus, OH 43212, USA.

Jianjie Ma, Department of Surgery, Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Greg J Beilman, Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

FUNDING

This work is partially supported by Department of Defense grant PR170989—“Developing MG53 as a Novel Protein Therapeutic for Acute Lung Injury” and the National Institutes of Health SBIR Award.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brogden TG, Bunin J, Kwon H, Lundy J, McD Johnston A, Bowley DM: Strategies for ventilation in acute, severe lung injury after combat trauma. J R Army Med Corps 2015; 161: 14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cai C, Masumiya H, Weisleder N, et al. : MG53 nucleates assembly of cell membrane repair machinery. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11(1): 56-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai C, Masumiya H, Weisleder N, et al. : MG53 regulates membrane budding and exocytosis in muscle cells. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 3314-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cai C, Weisleder N, Ko JK, et al. : Membrane repair defects in muscular dystrophy are linked to altered interaction between MG53, caveolin-3, and dysferlin. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 15894-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McNeil P: Membrane repair redux: redox of MG53. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11: 7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hwang M, Ko JK, Weisleder N, Takeshima H, Ma J: Redox-dependent oligomerization through a leucine zipper motif is essential for MG53-mediated cell membrane repair. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011; 301(1): C106-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burkin DJ, Wuebbles RD: A molecular bandage for diseased muscle. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 139fs119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao CM, Zhang Y, Weisleder N, Ferrante C, Wang XH, Fengxiang LV: MG53 constitutes a primary determinant of cardiac ischemic preconditioning. Circulation 2010; 121(23): 2565-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jia Y, Chen K, Lin P, et al. : Treatment of acute lung injury by targeting MG53-mediated cell membrane repair. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weisleder N, Takizawa N, Lin P, et al. : Recombinant MG53 protein modulates therapeutic cell membrane repair in treatment of muscular dystrophy. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 139ra185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J, Zhu H, Zheng Y, et al. : Cardioprotection of recombinant human MG53 protein in a porcine model of ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015; 80: 10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhu H, Hou J, Roe JL, et al. : Amelioration of ischemia-reperfusion-induced muscle injury by the recombinant human MG53 protein. Muscle Nerve 2015; 52: 852-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iyegha UP, Greenberg JJ, Mulier KE, Chipman J, George M, Beilman GJ: Environmental hypothermia in porcine polytrauma and hemorrhagic shock is safe. Shock. 2012; 38: 387-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colling KP, Iyegha UP, Asghar JI, et al. : Preinjury fed state alters the physiologic response in a porcine model of hemorrhagic shock and polytrauma. Shock 2015; 44(Suppl 1): 103-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitson BA, D’Cunha J: Ex vivo lung perfusion and extracorporeal life support in lung transplantation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 23: 176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nelson K, Bobba C, Eren E, et al. : Method of isolated ex vivo lung perfusion in a rat model: lessons learned from developing a rat EVLP program. J Vis Exp 2015; 96: 52309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cypel M, Keshavjee S: Extracorporeal lung perfusion (ex-vivo lung perfusion). Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2016; 21: 329-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duann P, Li H, Lin P, et al. : MG53-mediated cell membrane repair protects against acute kidney injury. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 279ra236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li H, Duann P, Lin PH, et al. : Modulation of wound healing and scar formation by MG53 protein-mediated cell membrane repair. J Biol Chem 2015; 290(40): 24592-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bian Z, Wang Q, Zhou X, et al. : Sustained elevation of MG53 in the bloodstream increases tissue regenerative capacity without compromising metabolic function. Nat Commun 2019; 10(1): 4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang X, Xie W, Zhang Y, et al. : Cardioprotection of ischemia/reperfusion injury by cholesterol-dependent MG53-mediated membrane repair. Circ Res 2010; 107(1): 76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harleman JH, Nolte T: Testicular toxicity: regulatory guidelines—the end of formaldehyde fixation? Toxicol Pathol 1997; 25(4): 414-7. discussion 418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Latendresse JR, Warbrittion AR, Jonassen H, Creasy DM: Fixation of testes and eyes using a modified Davidson‘s fluid: comparison with Bouin’s fluid and conventional Davidson’s fluid. Toxicol Pathol 2002; 30(4): 524-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creasy DM: Evaluation of testicular toxicology: a synopsis and discussion of the recommendations proposed by the Society of Toxicologic Pathology. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 2003; 68(5): 408-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]