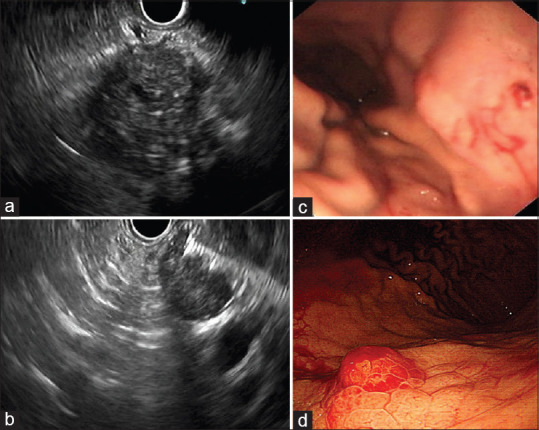

A 33-year-old man presented with a 1-month history of upper abdominal discomfort. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a diffusely enlarged pancreas with uneven enhancement. IgG4 levels were elevated (24,100 mg/L, normal: 80–1400 mg/L), but platelets and coagulation tests were normal. An EUS-FNA was performed (once, ten strokes) with a 19-gauge needle (BostonScientific, Expect™, 19G) [Figure 1a and b]; no significant bleeding was observed [Figure 1c]. On day 6 after EUS-FNA, the patient presented with sudden-onset hematemesis and melena together with a significant decrease in serum hemoglobin (120 g/L to 93 g/L). Upper endoscopy showed bulging of the stomach mucosa consistent with the EUS-FNA puncture site and bleeding from the center of the lesion [Figure 1d]. Titanium clips were used to close the wound, and no further bleeding occurred. Pathological findings of EUS-FNA confirmed the diagnosis of Type I autoimmune pancreatitis, and the patient was started on steroids after the bleeding stopped.

Figure 1.

EUS-FNA of the patient. (a) EUS showed diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, with hypoechoic parenchyma and multiple dot-like and linear hyperechoic lesions. (b) EUS-FNA was performed (once, ten strokes) with a 19-gauge needle. (c) No significant bleeding was observed just after the procedure. (d) An emergency upper endoscopy showed mucosal swelling at the upper posterior wall of the body of the stomach consistent with the puncture site, with bleeding on day 6 after EUS-FNA

The incidence of bleeding due to EUS-FNA of pancreatic lesions is reported to be 0%–1%, with most hemorrhage occurring during the procedure or within 3 days.[1] Delayed bleeding is extremely rare. We performed a literature review and found three other published cases of delayed hemorrhage after EUS-FNA of pancreatic lesions [Table 1].[2,3,4] The time of bleeding ranged from 6 days to 3 weeks after the procedure, and the site of bleeding included intramural hematoma, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and mucosal damage at the puncture site. Two of four patients were on anticoagulants. A 19-guage needle was used in two cases, while a 22-gauge needle was used in the other two cases. While three of four cases recovered, one patient on anticoagulants died due to uncontrolled retroperitoneal hemorrhage. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an autoimmune pancreatitis patient experiencing delayed bleeding after EUS-FNA. Although IgG4-related disease has been reported to cause acquired hemophilia,[5] our patient had completely normal coagulation tests and he was not on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy. The cause of delayed bleeding in the current case remains unknown, but possible explanations might include needle injury to one of the penetrating gastric arteries. Endoscopists must be aware of the uncommon yet possible delayed bleeding complication of EUS-FNA.

Table 1.

Published cases of delayed bleeding after EUS-FNA of pancreatic lesions

| Author/year | Sex/age | Lesion | Pathology | FNA | Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy | Time of bleeding | Bleeding lesion | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roseira et al., 2019 [3] | Male/65 | A pancreatic head mass in the setting of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis | Not mentioned | 22G needle, 3 passes from duodenal bulb | No | 3 weeks after EUS-FNA | Intramural duodenal hematoma | Conservative therapy. Improvement within 15 days |

| Sendino et al., 2010 [4] | Not mentioned | Cystic pancreatic lesion | Not mentioned | 19G needle, with EchoBrush | Anticoagulation therapy stopped 2 days before EUS-FNA | 1 week after EUS-FNA | Retroperitoneal hemorrhage | Died |

| Tomoya et al., 2015 [2] | Male/64 | A pancreatic body mass | Invasive pancreatic ductal cancer | 22G needle, 2 passes, 10 strokes each | Edoxaban started after EUS-FNA to treat inferior vena cava thrombi | 10 days after EUS-FNA | An ulcer at the puncture site on a background of atrophied gastric mucosa | Coagulation hemostasis performed with coagulation forceps, recovery |

| Our case | Male/33 | Diffusely enlarged pancreas | Type I autoimmune pancreatitis | 19G needle, 1 pass, 10 strokes | No | 6 days after EUS-FNA | Mucosal swelling at the puncture site with bleeding | Titanium clips, recovery |

FNA: Fine needle aspiration

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoshinaga S, Itoi T, Yamao K, et al. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for pancreatic masses: A prospective multicenter study. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:114–26. doi: 10.1111/den.13457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iida T, Adachi T, Nakagaki S, et al. Hemorrhagic gastric ulcer after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Endoscopy. 2015;47(Suppl 1):E635–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roseira J, Cunha M, Tavares de Sousa H, et al. Delayed intramural duodenal hematoma after a simple diagnostic endoscopic ultrasonography fine-needle aspiration procedure. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00279. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sendino O, Fernández-Esparrach G, Solé M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided brushing increases cellular diagnosis of pancreatic cysts: A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:877–81. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Duan W, Zhu X, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related acquired hemophilia: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3988–92. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]