Abstract

Background

Withholding cancer-related concerns from one’s partner (protective buffering) and feeling that one’s partner is inaccessible or unresponsive to such disclosure (social constraints) are two interpersonal interaction patterns that separately have been linked to poorer adjustment to cancer.

Purpose

Guided by the Social-Cognitive Processing Model, we examined the joint effects of social constraints and protective buffering on fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) in survivors and spouses. Social constraints and protective buffering were hypothesized to emerge as independent predictors of higher FCR.

Methods

Early-stage breast cancer survivors and spouses (N = 79 couples; 158 paired individuals) completed up to five repeated measures of FCR, social constraints, protective buffering, and relationship quality during the year postdiagnosis. A second-order growth curve model was estimated and extended to test the time-varying, within-person effects of social constraints and protective buffering on a latent FCR variable, controlling for relationship quality.

Results

As hypothesized, greater social constraints and protective buffering significantly (p < .05) predicted higher concurrent FCR at the within-person level, controlling for global relationship quality and change in FCR over time. The fixed effects were found to be similar for both survivors and spouses.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that interaction patterns resulting in inhibited disclosure are associated with greater FCR for both survivors and spouses, consistent with the Social-Cognitive Processing Model. This work adds to the growing body of research highlighting the social context of FCR.

Keywords: Close relationships, Fear of cancer recurrence, Disclosure, Social constraints, Protective buffering

Over the first year of breast cancer survivorship, when patients or their intimate partners felt unable to share cancer-related concerns with one another, they reported higher levels of fear of cancer recurrence.

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR), defined as “fear, worry, or concern about cancer returning or progressing” [1], is among the most common psychosocial difficulties and top unmet need reported by cancer survivors [2, 3] and their spouses/intimate partners (hereafter termed spouses, regardless of marital status) [2, 4–6]. Higher FCR has been linked to more psychological distress and functional impairment [2], depression [7], and poorer quality of life [2]. The clinical relevance of FCR expands beyond psychosocial functioning, with recent work showing associations between FCR and cancer surveillance (self-checking) behavior [8], health care utilization [9], sleep [10], and other health behaviors [11].

Emerging evidence points to the importance of intimate relationships for understanding FCR [12–17]. Recently incorporated in an integrated model of FCR [18], the Social-Cognitive Processing Model (SCPM) provides a conceptual framework for understanding how close relationships may serve to regulate FCR in survivorship [19, 20]. The SCPM emphasizes the importance of an individual’s social network for facilitating cognitive processing of cancer-related memories, thoughts, and concerns. The model suggests that sharing these concerns with a responsive, close other (the current study focuses on the spouse, who is typically the most influential social tie among partnered individuals [21]) is an adaptive response to stressful events, such as cancer. When the spouse is perceived as responsive and available, disclosure is hypothesized to facilitate cognitive processing via habituation, memory consolidation, and the integration of cancer-related experiences with views of the self, others, and the world [19, 20]. Disclosure also offers opportunities for support provision and receipt, meaning-making, and a communal, collaborative approach to coping with shared worries.

According to the SCPM, when an individual withholds disclosure of cancer-related concerns to his/her spouse, cognitive processing is thwarted or delayed, which maintains cancer-related distress and hinders adjustment. The SCPM identifies social constraints as a central source of inhibited disclosure [20]. Social constraints reflect the perception that one cannot share cancer-related thoughts, concerns, or worries with one’s spouse due to his/her disinterest, unavailability, or disapproval (real or imagined) [20]. Partner disclosure of concerns is also identified as an important mechanism of adjustment to illness in models of dyadic coping [22]. In this related line of work, protective buffering is defined as “efforts to protect one’s partner from upset and burden by concealing worries, hiding concerns, and yielding to the partner to avoid disagreements [23].” Thus, protective buffering describes an internal source of inhibited disclosure—that is, an internal motivation to protect one’s partner and/or to “keep things on an even keel” in the relationship [24]. In the context of the SCPM, protective buffering is a self-imposed constraint on disclosure, thus restricting access to the cognitive and emotional benefits of this social regulation strategy, and in turn, impeding adjustment and maintaining FCR.

From the perspective of the SCPM, social constraints and protective buffering share a common function: they both result in the absence of open, authentic, and validated disclosure of cancer-related concerns to the spouse. Social constraints inhibit disclosure via perceptions of the spouse as unavailable, uninterested, critical, or otherwise avoidant of one’s sharing. An individual who perceives social constraints is less likely to disclose concerns or fears due to these perceptions. Further, to the extent that these perceptions reflect an accurate prediction of partner nonresponsiveness, any disclosure attempts that are made are unlikely to facilitate adaptive processing. In contrast, protective buffering inhibits disclosure via an individual’s own efforts to avoid triggering distress in his/her partner (or other perceived consequences of sharing cancer-related concerns). Both processes are defined in part by a barrier to sharing and processing cancer-related concerns with an available and responsive partner.

In support of the SCPM, several studies have linked social constraints to impaired cognitive processing (operationalized as increased intrusive thoughts and cognitive avoidance) [4, 7], and a recent meta-analysis found moderate-sized associations between social constraints and distress in cancer patients [25]. Two studies investigated the effects of social constraints on FCR. Consistent with the SCPM and integrated models of FCR [18], both found that social constraints predicted greater FCR in cancer patients and their spouses [4, 13]. Protective buffering also has been empirically linked to poorer adjustment in couples with cancer. In patients and spouses, protective buffering has been linked to higher levels of distress [23] and depression [26] and poorer health-related self-efficacy [26] and overall mental health [27]. In the only prior study that examined protective buffering and FCR, Perndorfer et al. found that both patients and spouses reported more FCR on days on which they also endorsed buffering their spouse [12].

In sum, prior research supports the notion that one’s own disclosure is an important strategy for regulating and tolerating their own concerns about cancer recurrence (actor effects). A separate but related question is whether one partner’s inhibited disclosure not only hinders his/her own adjustment, but also his/her partner’s adjustment (partner effects). To our knowledge, only one study has examined partner effects of social constraints on cancer adjustment: across two independent samples, the study failed to find consistent evidence for such effects (for patients or spouses) [13]. More studies have examined partner effects of protective buffering, but the results have been inconsistent [12, 23, 27, 28].

The SCPM conceptualizes disclosure to close others as a vital mechanism of adaptation to major life events, including cancer—both social constraints and protective buffering hinder access to this key social regulation strategy [29]. To our knowledge, social constraints and protective buffering have not been studied from this perspective, and no published studies report independent or joint effects of social constraints and protective buffering on adjustment outcomes. Yet, estimating their unique contributions is an important test of the SCPM, and more specifically, the overarching hypothesis that either source of inhibited disclosure would hinder adjustment. Indeed, many of the studies reviewed above focused on the unique features of social constraints or protective buffering rather than their underlying shared function. A theory-based integration of these lines of work would help to drive research progress by bridging related constructs from seemingly disparate literatures under a shared conceptual framework.

The Current Study

The aim of the current study was to examine the joint effects of social constraints and protective buffering on FCR in early-stage breast cancer patients and their spouses over the first year postdiagnosis. Patients and spouses completed up to five repeated panel assessments between study enrollment (about 4 months after breast cancer surgery) and the first follow-up mammogram (about 1 year postdiagnosis). Several validated measures of FCR were used to separate reliable from unique variance and allow creation of a latent FCR outcome variable considered free of measurement error. As highlighted elsewhere [13], the dynamic processes described in both the SCPM and theories of FCR [18, 30–33] are proposed to unfold within-person over time. Similarly, psychotherapeutic interventions, including those newly developed for FCR, are designed to facilitate within-person change over time. Thus, a longitudinal design and within-person focus is essential to test the SCPM and render clinically applicable findings to inform ongoing intervention development. Further, the current study used global measures that assessed the constructs of interest over a long period (1 month), providing data to complement and corroborate prior findings from cross-sectional [4, 13] and daily diary studies [12, 13].

It was hypothesized that social constraints and protective buffering would each emerge as independent predictors of greater FCR, at the within-person level, for both patients and spouses. These effects were expected to persist after controlling for a plausible confounding factor—global relationship quality—which has been linked not only to FCR [13], but also to social constraints [34] and protective buffering [27]. The importance of disclosure-responsiveness patterns for intimacy and relationship quality has been established in the broader literature, collectively suggesting that social constraints and protective buffering undermine these aspects of relationship functioning [35, 36]. Thus, controlling for the effects of global relationship functioning is critical to testing the hypothesis that inhibited disclosure of cancer-related concerns (rather than more general communication patterns) impedes regulation of FCR. There was little theoretical rationale to expect partner effects of social constraints and/or protective buffering which, as discussed above, were not found in prior studies. Therefore, this study focuses on the effects of an individual’s inhibited disclosure on their own (but not their partner’s) FCR, but partner effects were also examined as an exploratory aim.

Method

Participants

Female early-stage breast cancer patients and their spouses were recruited from a U.S. community cancer center for the Surviving Cancer Together study, which was approved by the Christiana Care Health System IRB (FWA00006557; CCC# 33026). Sampling and recruitment flow are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) 1. Patients were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (a) diagnosed with Stage 0 through IIIA breast cancer, (b) had recent breast cancer surgery, (c) were in a committed relationship with a partner who also agreed to participate, (d) spoke English, (e) lived within an hour of the recruitment site, and (f) did not have prior cancer diagnoses. Older patients were found more likely to decline participation than younger patients, but those decliners and participants did not significantly differ with regard to cancer stage (reported by Soriano et al. [13]).

Seventy-nine couples (N = 158 paired individuals) participated in the parent study and constitute the sample analyzed here. Most couples (93%) were married. Most spouses were male (n = 2 females). On average, patients and spouses were 57.18 (SD = 9.40) and 59.38 (SD =10.39) years old, respectively. Most participants were Caucasian (patients: 87.2%; spouses: 83.3%); none were Hispanic/Latino. Twelve and 14% of patients and spouses, respectively, identified as Black or African-American, with the remaining (patients: 1.3%, spouses: 2.6%) identifying as Asian. About 37% reported an annual household income exceeding $100,000. About 14% of patients were diagnosed with Stage 0 breast cancer, 47% Stage I, 37% Stage II, and 2% Stage IIIa. The majority (77%) had breast-conserving surgery (vs. mastectomy). About a quarter of patients had reconstructive breast surgery at some point during participation in the study. About a third of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, 70% radiotherapy, and 77% hormonal therapy (all patients completed treatment by T2, as described below).

Procedure

Couples were invited to start the study after the patient’s breast cancer surgery and were followed until the patient’s first follow-up mammogram postdiagnosis (typically 1 year after initial diagnostic mammogram). Over the course of the study, participants were emailed links to online surveys, to be completed independently at home, on as many as five occasions (M = 3.53, SD = 0.95). The first survey (T1) took place before the start of adjuvant treatment or, for those not receiving adjuvant treatment, upon informed consent (M months between surgery and T1 = 3.55, SD = 1.69). The second survey (T2) took place at the end of adjuvant treatment, or, if not applicable, approximately 3 months after T1. The timing of remaining surveys was individualized, such that the final (fifth) survey (T5) was sent 2 weeks before the patient’s annual mammogram appointment, with additional surveys scheduled at approximately equivalent intervals between T2 and T5. This flexible and individualized timeline yielded significant variability in the timing of and between surveys. On average, 2.77 months elapsed between each survey (SD = 0.67). The mean length of time between T1 and T5 was 7.04 months (SD = 2.19). Attrition at each time point is shown in ESM 1.

Though not examined in this report, the parent study also involved two daily diary period bursts (administered after the first and fifth surveys). Analysis of the daily diary data is reported elsewhere [8, 12–14, 17]. Using these data, associations between daily FCR and daily social constraints were reported by Soriano et al. [13], and associations between daily FCR and daily protective buffering were reported by Perndorfer et al. [12]. In the current paper, repeated global survey data from the same study, which have not been analyzed in prior reports, are used to expand on these daily diary findings. Thus, none of the data analyzed here overlap with those analyzed in prior publications.

Measures

Fear of recurrence

To create a latent FCR factor, three validated measures tapping core aspects of FCR [37–39] were used as manifest indicators. Measures were administered to both partners and assessed fears related to the possibility of the patient’s breast cancer recurring. The first indicator, the Severity subscale of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI [40]) is a sum of nine items assessing intrusive thoughts about and perceived risk of recurrence. The second indicator, the Distress subscale of the FCRI, is a sum of four items assessing emotional responses to thoughts of recurrence. Items from the FCRI Severity and Distress subscales were rated on a scale from zero to four, with higher scores indicating greater FCR. The third indicator, the Overall Fear subscale of the Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS [3]), is a sum of four items assessing the frequency, intensity, and distress associated with FCR. Items from the CARS measure were rated on a scale of one to six, with greater scores also indicating more FCR. The FCRI assessed FCR over the prior month, while the CARS assessed FCR generally without specifying a time frame. The omega coefficient was used to assess reliability of change for multi-item repeated measures [41]. The within-person reliability of the three indicators was strong for patients and spouses (ω = .89 for both).

Social constraints

The 15-item Social Constraints Scale was administered to both partners [42]. Items assess perceived constraints on disclosure of cancer-related thoughts, feelings, or behaviors to one’s partner over the past month. A sample patient item is, “How often did your spouse/partner change the subject when you tried to discuss your illness?” The spouse version of this item is, “How often did your spouse/partner change the subject when you tried to discuss her illness [emphasis added]?” All items were rated from zero (“never”) to three (“often”) and were averaged to create a composite score. Social constraints demonstrated strong within-person reliability for both patients (ω = .92) and spouses (ω = .91).

Protective buffering

A seven-item protective buffering measure was administered to patients and spouses [28]. Participants rated the extent to which they engaged in seven behaviors “to deal with your spouse or partner concerning issues arising from your/your partner’s cancer during the past month.” Example behaviors include “deny or hide my anger,” and “act more positive than I feel.” Items were rated from zero (“never”) to four (“very often”), and were averaged to create a composite, which had strong within-person reliability for patients (ω = .92) and spouses (ω = .91).

Relationship quality

Relationship quality, a key covariate, was assessed with the Quality of Marriage Index [43]. Five items were rated from one (“very strongly disagree”) to seven (“very strongly agree”) and a sixth item (“All things considered, what degree of happiness best describes your relationship?”) was rated from one (“very unhappy”) to ten (“perfectly happy”). Items were summed to create a composite, which had strong within-person reliability for patients (ω = .96) and spouses (ω = .95).

Data Analytic Strategy

Multilevel structural equation modeling was used to accommodate dependencies of repeated measures within persons and partners within couples. Analyses were conducted in Mplus (version 8 [44]) using robust maximum likelihood estimation, which provides valid inferences assuming data are missing at random. A second-order growth curve model [45], including a longitudinal measurement component and latent growth curve component, was applied to model growth in a latent FCR factor over the study duration. To test the hypothesis that social constraints and protective buffering would each exert independent effects on FCR, patient and spouse FCR was modeled as a function of time, social constraints, protective buffering, and relationship quality. As indicated earlier, the main hypothesis concerns the effects of an individual’s inhibited disclosure on his/her own FCR (actor effects). However, in a post hoc exploratory analysis, the fixed effects of an individual’s inhibited disclosure on his/her partner’s FCR (partner effects) were also added to this main model.

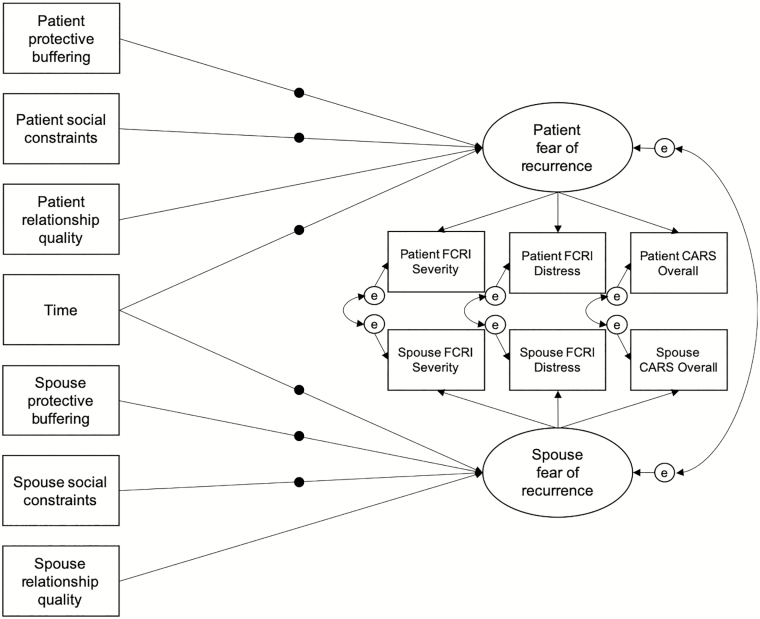

To obtain pure within-person effects, the FCR factor indicators (see above), time, social constraints, protective buffering, and relationship quality were person-mean centered. Figure 1 depicts the tested model. Note that this longitudinal modeling approach examines concurrent, within-person associations, which are different than cross-sectional associations that assess between-person differences. We focused on concurrent rather than lagged associations (e.g., the effects of inhibited disclosure on FCR at a later time point) for multiple reasons. First, extant theoretical and empirical work does not offer hypotheses about the particular time lag that would be optimal to detect such an effect. Second, lagged analyses reduce power (i.e., fewer data points) and increase model complexity (i.e., more parameters estimated), which may be problematic with our current sample size (N = 79 couples and maximum of five time points). For these reasons, the results of such an analysis would be difficult to interpret.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of the within-person component of the multilevel second-order growth curve model tested. Filled circles on paths represent random slopes. At the between-person level (not shown), all random slopes were allowed to covary. CARS Concerns about Recurrence Scale; FCRI Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory.

As part of the second-order growth curve model, a within-person confirmatory factor analysis created a within-person latent FCR factor free of measurement error for patients and for spouses [45]. Three manifest indicators were used to create each partner’s latent factor: the FCRI Severity subscale, FCRI Distress subscale, and CARS Overall subscale. The loading for the FCRI Severity subscale was fixed to one to facilitate model identification and scale the latent variables. The patient and spouse latent factors were allowed to covary, as were patient and spouse factor indicator residuals. Estimation of random effects in the latent growth curve part of the model (described below) precludes calculation of global fit statistics. Therefore, relative fit was assessed with likelihood ratio deviance tests. Using this multilevel SEM approach, measurement invariance over time is assumed and cannot be directly tested. However, invariance of the patient and spouse FCR factor structures was examined with Satorra–Bentler χ 2 difference tests on constrained and unconstrained models [46].

Implemented in Mplus8 [44], growth in the patient and spouse latent FCR factors was modeled with individually varying time scores to account for variability in the timing of repeated assessments (see Procedure section). Random time slopes were estimated to allow for between-person heterogeneity in FCR growth over time. The latent factors of patient and spouse FCR were regressed on patient and spouse social constraints, protective buffering, and relationship quality, respectively. Random slope effects were estimated for the focal predictors, protective buffering and social constraints. At the between-person level, random slopes for time, social constraints, and protective buffering were allowed to covary. As stated earlier, effects at the within-person level are viewed as most consistent with the underlying theoretical framework and most relevant to ongoing FCR intervention development; therefore, to promote model convergence and parsimony, between-person effects were not estimated.

Results

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The within-person correlations among study variables are shown in ESM 2. Using a cutoff score ≥13 on the FCRI Severity [47], 26% of patients and 19% of spouses reported clinical levels of FCR at T1 (or earliest valid time point).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Mean | Within-person SD | Between-person SD | Possible range | Intraclass correlation | Total observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||||||

| FCRI Severity | 7.77 | 3.09 | 3.46 | 0–36 | .56 | 275 |

| FCRI Distress | 1.26 | 1.58 | 1.25 | 0–16 | .38 | 275 |

| CARS Overall | 10.01 | 2.44 | 3.22 | 4–24 | .64 | 275 |

| Social constraints | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0–3 | .56 | 275 |

| Protective buffering | 1.05 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0–4 | .51 | 275 |

| Relationship quality | 39.77 | 3.51 | 5.59 | 6–45 | .72 | 275 |

| Spouse | ||||||

| FCRI Severity | 5.83 | 2.67 | 3.18 | 0–36 | .59 | 272 |

| FCRI Distress | 1.12 | 1.42 | 1.51 | 0–16 | .53 | 271 |

| CARS Overall | 9.50 | 2.68 | 3.92 | 4–24 | .68 | 272 |

| Social constraints | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0–3 | .49 | 272 |

| Protective buffering | 1.31 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0–4 | .33 | 272 |

| Relationship quality | 39.70 | 3.80 | 4.73 | 6–45 | .61 | 272 |

Note. CARS Concerns about Recurrence Scale; FCRI Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory.

Relative fit of a model in which factor loadings were constrained to be equal for patients and spouses was tested against a model in which these loadings were freely estimated for both partners. The constrained factor loading model did not have significantly poorer fit, χ 2(2) = 2.06, p = .356, suggesting that a single set of factor loadings could be used for patients and spouses (supporting measurement invariance). The standardized (within-person) loadings of FCRI Severity, FCRI Distress, and CARS Overall for patients were 0.85, 0.56, and 0.65, respectively (all p < .001). For spouses, the standardized loadings were 0.76, 0.44, and 0.46, respectively (all p < .001). Equivalent model fit was obtained after constraining the patient and spouse regression coefficients linking FCR to time (χ 2(1) = 0.04, p = .843), social constraints (χ 2(1) = 0.12, p = .732), protective buffering (χ 2(1) = 0.09, p = .763), and relationship quality (χ 2(1) = 0.12, p = .725) to be equal (note that although patient and spouse (raw) factor loadings were constrained to be equal, standardization yields different estimates).

The results of the final model are detailed in Table 2. The fixed effect of the individually varying time variable was statistically significant and negative, indicating that, on average, the patient and spouse latent FCR factors decreased by 0.17 units each month. Thus, the model predicted approximately a two-unit decrease in patient and spouse FCR over the first year after diagnosis. As noted above, the patient and spouse FCR factors were given the same scale as the FCRI Severity subscale, which had a within-person standard deviation of about 3 in this sample and a possible range of 0–36. There was substantial variability in this fixed effect, with 95% of time slopes falling between −0.92 and 0.58 for patients and −0.82 and 0.49 for spouses.

Table 2.

Multilevel second-order growth curve modeling results

| Effect | Estimate | Standard error | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Outcome: Patient fear of recurrence | ||||

| Patient social constraints | ||||

| Fixed effecta | 1.117* | 0.538 | 0.062 | 2.171 |

| Random effect (SD) | 1.224 | 2.782 | −3.955 | 6.95 |

| Patient protective buffering | ||||

| Fixed effectb | 1.102*** | 0.273 | 0.567 | 1.637 |

| Random effect (SD) | 1.437 | 2.427 | −2.692 | 6.82 |

| Time (months) | ||||

| Fixed effectc | −0.168** | 0.050 | −0.266 | −0.070 |

| Random effect (SD) | 0.382 | 0.089 | −0.029 | 0.321 |

| Patient relationship qualityd | 0.065† | 0.036 | −0.006 | 0.137 |

| Outcome: Spouse fear of recurrence | ||||

| Spouse social constraints | ||||

| Fixed effecta | 1.117* | 0.538 | 0.062 | 2.171 |

| Random effect (SD) | 3.072 | 6.153 | −2.623 | 21.497 |

| Spouse protective buffering | ||||

| Fixed effectb | 1.102*** | 0.273 | 0.567 | 1.637 |

| Random effect (SD) | 2.057† | 2.193 | −0.067 | 8.529 |

| Time (months) | ||||

| Fixed effectc | −0.168** | 0.050 | −0.266 | −0.070 |

| Random effect (SD) | 0.333† | 0.067 | −0.021 | 0.243 |

| Spouse relationship qualityd | 0.065† | 0.036 | −0.006 | 0.137 |

Note. The fear of recurrence latent factors follow the same scale as their first indicators, the FCRI Severity subscale, which has a possible range of zero to 36. For random effects, confidence intervals are provided in variance units.

a,b,c,dCorresponding coefficients constrained to be equal across partners.

† p < .10.

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

***p < .001.

Social constraints were a statistically significant predictor of greater FCR for both partners. The fixed effect indicated a predicted 1.12-unit increase in FCR for a one-unit increase in social constraints. This slope varied for patients, for whom 95% of slopes ranged between about −1.28 and 3.52. The effect of social constraints on FCR varied even more for spouses, with 95% of scores falling between −4.90 and 7.14.

Consistent with the hypothesis, the fixed effect of protective buffering was also a significant, positive predictor of FCR for patients and spouses. The fixed effect indicated that a one-unit increase in protective buffering predicted a 1.10-unit increase in latent FCR. Here, heterogeneity in slopes was notable for patients (95% of slopes between −1.72 and 3.92), and again, even more so for spouses (95% of slopes between −2.93 and 5.13). Finally, patient and spouse relationship quality were included as covariates, but neither emerged as statistically significant predictors of latent FCR above or beyond social constraints and protective buffering.

Using the actor–partner interdependence approach [48], this main model was extended to explore partner effects of social constraints and protective buffering on patient and spouse FCR. All parameters from the prior model were retained (the only change being the addition of these four fixed partner effects). Model fit supported constrained patient and spouse (actor and partner) effects of social constraints and protective buffering, χ 2(4) = 0.23, p = .994. The actor effects of social constraints (b = 1.16, SE = 0.54, p = .031) and protective buffering (b = 1.11, SE = 0.27, p < .001) both remained statistically significant. The effect of one partner’s social constraints on the other partner’s FCR was not significant, b = −0.12, SE = 0.45, p = .790. The partner effect of protective buffering on FCR was also not significant, b = −0.03, SE = 0.33, p = .932.

The interaction between social constraints and protective buffering was explored in a post hoc analysis. The interaction was not significant for patients (b = −0.14, p = .681; random effect SD = 0.45) or spouses (b = −0.27, p = .457; random effect SD = 0.67).

Discussion

This study sought to integrate and expand upon recent research on the social regulation of FCR, using the SCPM as a guiding framework. The SCPM posits that disclosing cancer-related concerns to a responsive partner facilitates adjustment in cancer survivorship [19, 20]. Two interaction patterns that inhibit this disclosure—social constraints and protective buffering—have been empirically linked to FCR [12, 13] but have not yet been conceptually integrated and their joint effects have not been tested. This study examined the independent and simultaneous effects of social constraints and protective buffering on FCR in breast cancer survivors and their spouses over the first year postdiagnosis. We hypothesized that social constraints and protective buffering would each emerge as significant within-person predictors of greater FCR.

Results supported our hypothesis. Social constraints and protective buffering emerged as independent predictors of greater FCR, and the direction and size of effects were similar for patients and spouses. This suggests that when a patient or spouse perceived his/her partner as disinterested, unavailable, or critical in response to disclosure of cancer-related concerns (social constraints), he/she was found to have higher FCR compared with when he/she reported fewer constraints. Similarly, when a person reported withholding disclosure to protect his/her partner (protective buffering), this was associated with a corresponding within-person increase in FCR—above and beyond the effects of social constraints. By showing independent effects of two processes that stymie disclosure of cancer-related concerns to a responsive partner, these results provide strong support for the SCPM. In addition, there was substantial variability in the key effects between individuals (particularly spouses)—results indicated that the effect of inhibited disclosure on FCR was even stronger than the average fixed effect for some participants and for others, it was actually negative. Future research is needed to explore person-level characteristics that might moderate these associations, which could in turn identify who would benefit most from intervention. Critically, results suggest that the effects of inhibited disclosure on FCR were not explained by global relationship dysfunction, which is often associated with inhibited disclosure of emotional content broadly [35], providing further support for the idea that concerns about recurrence are processed and ultimately reduced via sharing with a responsive partner.

The present results are consistent with prior studies of social constraints [13, 25] and protective buffering [12, 23, 27, 28] in couples coping with illness. Our findings add to a small but growing body of work suggesting both that (a) individuals with more inhibited disclosure have higher FCR than individuals with less inhibited disclosure (between-person) and (b) individuals tend to have higher FCR when they report more inhibited disclosure compared with when they report less inhibited disclosure [12, 13]. By measuring variables globally (with respect to the prior month), this study also builds upon and corroborates results of daily diary studies [12, 13]. Compared with the global measures used here, daily inhibited disclosure measures are likely more reflective of specific interactions and reliant on episodic memory [49]. The convergence of effects across these approaches suggests that both global evaluations and daily experiences of inhibited disclosure from one’s spouse are related to higher FCR. Another strength of this study was its longitudinal design. The SCPM [20] and theories of FCR [18, 30–33] detail processes that unfold within-person over time and thus longitudinal studies and estimates of within-person effects are key tools for testing these models. Another advantage of within-person effects is that, by definition, they cannot be confounded by time-invariant, person-level variables. This means that our findings cannot be explained or confounded by, for example, disease characteristics such as cancer stage, treatment type, or other stable person-level factors.

Effects of one partner’s inhibited disclosure on the other partner’s FCR (partner effects) were also explored, but none were significant (for patients or spouses). These null findings are consistent with the results of a few prior studies that examined partner effects of social constraints [13] and protective buffering [12] on FCR. This pattern of findings suggests that one partner’s inhibited disclosure may not necessarily correspond to the other partner’s distress or needs for cognitive processing at a given point in time. Perhaps this reflects that within-dyad, partners likely differ from one another in their need and/or desire for disclosure of cancer-related concerns, and the extent that they differ probably fluctuates as needs change over time. Indeed, there are likely many factors that contribute to a lack of partner accessibility or responsiveness to cancer-related disclosure (e.g., an unawareness of the other’s distress due to distraction or misreading of cues), and these factors likely vary in their relevance to the other partner’s FCR. Similarly, there are likely many factors that drive an individual to avoid discussions about a shared major stressor via protective buffering, including efforts to avoid his/her own emotional distress or distorted predictions of the partner’s response or ability to cope, which may have weaker direct effects on the partner’s adjustment. Attachment theory suggests that the regulatory success of disclosure in close relationships is largely driven by a person’s “subjective appraisal” of partner accessibility and responsiveness to cancer-related disclosure, which should be related to but not wholly captured by that partner’s own report of avoidance of such discussions [35, 36]. Attachment theory may also be particularly useful for future investigations of person-level characteristics (e.g., attachment style) that contribute to the between-person variability we observed in the random effects of inhibited disclosure on FCR.

Taken together, these findings tentatively suggest that focusing on the different intra- and interpersonal processes that can give rise to inhibited disclosure in couples could be of unique value for psychosocial interventions for cancer-related adjustment (e.g., FCR). To our knowledge, interventions for FCR have yet to incorporate patients’ significant others or target social processes [50]. A recent meta-analysis of FCR interventions, most of which were a form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or “third-wave” CBT (e.g., mindfulness), found consistent but small effects on average [50]. Interestingly, third-wave approaches were found to be superior to traditional CBT interventions, leading the authors to conclude that treating broader maladaptive psychological processes that maintain FCR may be more effective than targeting FCR cognitions and related behavior alone [50]. We suggest that couple- and emotion-focused therapy modalities may also be particularly helpful, given the focus on process, rather than content, inherent in relationship dynamics (i.e., focus on disclosure-response patterns within the relationship rather than motivations, thoughts, or beliefs of individual partners). Dyadic interventions are ideally suited to reduce inhibited disclosure as they can more easily address both social constraints and protective buffering, and each partner’s respective role in both problematic patterns—that is, addressing inhibited disclosure arising from both within the individual (e.g., desire to protect one’s partner) and from the individual’s partner (e.g., dismissing the other partner’s concerns). For example, an emotionally focused couple therapy approach may accomplish this by facilitating each partner’s mutual understanding of and in vivo exposure to their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to thoughts and discussions of their own and each other’s FCR [36]. As a process-oriented, experiential, an attachment-based approach, emotionally focused couple therapy may be particularly well-positioned to address social constraints, protective buffering, and other independent sources of inhibited disclosure in couples coping with FCR. Individual interventions that address issues like experiential avoidance or emotional suppression also may have secondary benefits on FCR by reducing these common barriers to partner disclosure.

Due to limitations of this study, results should be considered tentative pending an appropriately powered replication. First, this observational study reported concurrent associations from which directionality or causality cannot be definitively inferred. Although inhibited disclosure is theorized to causally affect FCR [18–20], the reverse direction also seems plausible. An attachment perspective would argue that FCR is a threat that activates attachment needs, and if these needs are not met, an individual may turn to anxious (social constraints) or avoidant (protective buffering) attachment strategies [35, 36]. These bidirectional relationships will be important to model explicitly in a future study designed specifically to address this question. Second, the current sample characteristics limit generalizability to other populations, including male patients, female spouses, other cancer types, severely distressed individuals/couples, and those who are not Caucasian. Disentangling culture, gender, and role effects remains a challenge for couples health research; for example, a recent meta-analysis found little evidence that gender moderated effects of social constraints on distress in cancer patients [25], but other work shows gender differences in patterns of emotional expression and disclosure [51]. Because this sample reported low to moderate distress on average, future studies should test whether the effects of inhibited disclosure vary by level of FCR or relationship distress. It will be particularly important to demonstrate empirically that the current findings generalize to individuals/dyads who might actually need or seek treatment for FCR or related concerns (e.g., have scores exceeding recommended cutoff for clinical FCR on the FCRI Severity Scale [47]). At the same time, it is interesting that we found robust effects of inhibited disclosure on FCR even among those without clinically significant distress. Indeed, findings support a dimensional perspective of FCR and the value in studying the full spectrum of severity.

In summary, this study attempted to integrate prior research on social constraints [19, 20] and protective buffering [22] using the SCPM as a conceptual framework. Findings indicate that the sharing of cancer-related worries, thoughts, and distressing memories to a responsive, supportive, available close other is associated with less FCR for survivors and their spouses. The current findings add to a growing body of research that points to the importance of close relationships for understanding and potentially regulating FCR [12–17].

Funding

Work presented in this manuscript was generously supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA171921).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Emily C. Soriano, Amy K. Otto, Stefanie T. LoSavio, Christine Perndorfer, Scott D. Siegel, and Jean-Philippe Laurenceau declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions E.C.S. Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft, visualization, project administration; A.K.O. Investigation, writing-review & editing, project administration; S.T.L. Investigation, writing-review & editing, project administration; C.P. Writing-review & editing; S.D.S. Funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing-review & editing, project administration; J.P.L. Funding acquisition, conceptualization, resources, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, writing-review & editing, project administration.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, et al. ; University of Ottawa Fear of Cancer Recurrence Colloquium attendees . From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3265–3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vickberg SM. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohee AA, Adams RN, Johns SA, et al. Long-term fear of recurrence in young breast cancer survivors and partners: long-term fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors and partners. Psychooncology. 2017;26(1):22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, Love-Ghaffari M, Kaw CK. Dyadic effects of fear of recurrence on the quality of life of cancer survivors and their caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(3):517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mellon S, Kershaw TS, Northouse LL, Freeman-Gibb L. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2007;16(3):214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohee AA, Adams RN, Fife BL, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and social cognitive processing in partners of long-term breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(1):44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soriano EC, Valera R, Pasipanodya EC, Otto AK, Siegel SD, Laurenceau JP. Checking behavior, fear of recurrence, and daily triggers in breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(3):244–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Otto AK, Soriano EC, Siegel SD, LoSavio ST, Laurenceau JP. Assessing the relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and health care utilization in early-stage breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(6):775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berrett-Abebe J, Cadet T, Pirl W, Lennes I. Exploring the relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and sleep quality in cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33(3):297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Séguin Leclair C, Lebel S, Westmaas JL. The relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and health behaviors: a nationwide longitudinal study of cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2019;38(7):596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perndorfer C, Soriano EC, Siegel SD, Laurenceau JP. Everyday protective buffering predicts intimacy and fear of cancer recurrence in couples coping with early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(2):317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soriano EC, Pasipanodya EC, LoSavio ST, et al. Social constraints and fear of recurrence in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2018;37(9):874–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soriano EC, Perndorfer C, Otto AK, Siegel SD, Laurenceau JP. Does sharing good news buffer fear of bad news? A daily diary study of fear of cancer recurrence in couples approaching the first mammogram post-diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2581–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takeuchi E, Kim Y, Shaffer KM, Cannady RS, Carver CS. Fear of cancer recurrence promotes cancer screening behaviors among family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020; 126: 1784– 1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeLongis A, Morstead T. Bringing the social context into research using the common sense model. Health Psychol Rev. 2019; 13(4):481–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soriano EC, Perndorfer C, Siegel SD, Laurenceau JP. Threat sensitivity and fear of cancer recurrence: a daily diary study of reactivity and recovery as patients and spouses face the first mammogram post-diagnosis. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curran L, Sharpe L, Butow P. Anxiety in the context of cancer: a systematic review and development of an integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;56:40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lepore SJ. A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen BL, eds. Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001:99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lepore SJ, Revenson TA. Social constraints on disclosure and adjustment to cancer. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2007;1(1):313–333. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soriano EC, Otto AK, Siegel SD, Laurenceau JP. Partner social constraints and early-stage breast cancer: longitudinal associations with psychosexual adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2017;31(5):574–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falconier MK, Kuhn R. Dyadic coping in couples: a conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Front Psychol. 2019;10:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: the moderating role of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(3):380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coyne JC, Smith DA. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: a contextual perspective on wives’ distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(3):404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams RN, Winger JG, Mosher CE. A meta-analysis of the relationship between social constraints and distress in cancer patients. J Behav Med. 2015;38(2):294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kayser K, Sormanti M, Strainchamps E. Women coping with cancer: the influence of relationship factors on psychosocial adjustment. Psychol Women Q. 1999;23(4):725–739. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langer SL, Brown JD, Syrjala KL. Intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences of protective buffering among cancer patients and caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115(S18):4311–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suls J, Green P, Rose G, Lounsbury P, Gordon E. Hiding worries from One’s spouse: associations between coping via protective buffering and distress in male post-myocardial infarction patients and their wives. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):333–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychol. 2013;32(5):499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lebel S, Maheu C, Tomei C, et al. Towards the validation of a new, blended theoretical model of fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2594–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, Bebbington Hatcher M. Fear of cancer recurrence: a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology. 1997;6:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sharpe L, Thewes B, Butow P. Current directions in research and treatment of fear of cancer recurrence. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2017;11(3):191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simonelli LE, Siegel SD, Duffy NM. Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and its relevance for clinical presentation and management. Psychooncology. 2017;26: 1444–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhaoyang R, Martire LM, Stanford AM. Disclosure and holding back: communication, psychological adjustment, and marital satisfaction among couples coping with osteoarthritis. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(3):412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson SM. Emotionally focused couple therapy. In: Gurman AS, ed. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy. 4th ed.New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008:107–137. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Costa DSJ, Smith AB, Fardell JE. The sum of all fears: conceptual challenges with measuring fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Custers JAE, Gielissen MFM, de Wilt JHW, et al. Towards an evidence-based model of fear of cancer recurrence for breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mutsaers B, Jones G, Rutkowski N, et al. When fear of cancer recurrence becomes a clinical issue: a qualitative analysis of features associated with clinical fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(10):4207–4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(3):241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yip T, Bolger N. A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32(7):917–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lepore SJ, Ituarte PH. Optimism about cancer enhances mood by reducing negative social interactions. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1999;8:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Norton R. Measuring marital quality: a critical look at the dependent variable. J Marriage Fam. 1983;45(1):141. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grimm KJ, Ram N, Estabrook R. Growth Modeling: Structural Equation and Multilevel Modeling Approaches. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66(4):507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Simard S, Savard J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):481–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwarz N. Why researchers should think “real-time”: a cognitive rationale. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, Csikszentmihalyi M, eds. Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life. Paperback ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2012:22–42. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tauber NM, O’Toole MS, Dinkel A, et al. Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2019; 37(31):2899– 2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zakowski SG, Harris C, Krueger N, et al. Social barriers to emotional expression and their relations to distress in male and female cancer patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2003;8(3):271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.