Abstract

Introduction: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has multiorgan involvement and its severity varies with the presence of pre-existing risk factors like cardiovascular disease (CVD) and hypertension (HTN). Therefore, it is important to evaluate their effect on outcomes of COVID-19 patients. The objective of this meta-analysis and meta-regression is to evaluate outcomes of COVID-19 amongst patients with CVD and HTN.

Methods: English full-text observational studies having data on epidemiological characteristics of patients with COVID-19 were identified searching PubMed from December 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020, following Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) protocol. Studies having pre-existing CVD and HTN data that described outcomes including mortality and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) utilization were selected. Using random-effects models, risk of composite poor outcomes (meta-analysis) and isolated mortality and IMV utilization (meta-regression) were evaluated. Pooled prevalence of CVD and HTN, correlation coefficient (r) and odds ratio (OR) were estimated. The forest plots and correlation plots were created using random-effects models.

Results: Out of 29 studies (n=27,950) that met the criteria, 28 and 27 studies had data on CVD and HTN, respectively. Pooled prevalence of CVD was 18.2% and HTN was 32.7%. In meta-analysis, CVD (OR: 3.36; 95% CI: 2.29-4.94) and HTN (OR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.57-2.40) were associated with composite poor outcome. In age-adjusted meta-regression, pre-existing CVD was having significantly higher correlation of IMV utilization (r: 0.28; OR: 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1-1.6) without having any association with mortality (r: -0.01; OR: 0.9; 95% CI: 0.9-1.1) among COVID-19 hospitalizations. HTN was neither correlated with higher IMV utilization (r: 0.01; OR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.9-1.1) nor correlated with higher mortality (r: 0.001; OR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.9-1.1).

Conclusion: In age-adjusted analysis, though we identified pre-existing CVD as a risk factor for higher utilization of mechanical ventilation, pre-existing CVD and HTN had no independent role in increasing mortality.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19), novel coronavirus disease 2019, sars-cov-2, invasive mechanical ventilation, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, systematic review and meta-analysis, 2019-ncov, atrial fibrillation, risk factors

Introduction

In early December 2019, a large number of pneumonia cases were diagnosed in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease was later named as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and the causative agent is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. As of December, 2020, 69 million cases have been confirmed and 1.5 million people have died worldwide due to COVID-19 [2]. Common symptoms include fever, dry cough, fatigue, anorexia, myalgia and dyspnea [3]. In addition to the common symptoms, it is essential to know the impact of patients' comorbidities including cardiovascular disease (CVD) and hypertension (HTN) on COVID-19 outcomes. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may play an important role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 infection. Seventy-six percent of amino acid sequence of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is similar to SARS-CoV [4]. SARS-CoV-2 affects binding of human cells to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) an enzyme cleaving angiotensin II into angiotensin 1-7 [5]. SARS virus enters the cells via contact between the ACE2 receptor and the spike protein. SARS-CoV-2 may have more affinity towards ACE2 receptors in vitro [6].

According to a study performed in Brescia, Lombardy, Italy, patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease have poor prognosis (higher mortality, higher thromboembolic events and septic shock rates) compared to the patients without preexisting CVD [7]. COVID-19 usually results in mild symptoms but in some of infected patients, it can cause severe cardiac and lung disease [8]. Patients with CVD, especially heart failure, have a more severe clinical course once they are infected. The myocardial injury, which is demonstrated by an elevation in the troponin levels, has been noticed in at least 10% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a much higher percentage (25%-35%) noted when patients are severely ill with co-morbid CVD [5].

A study conducted by Guan et al. highlights that the patients with COVID-19 who develop severe pneumonia had higher rates of pre-existing HTN, diabetes, and CVD as compared to those who develop non-severe pneumonia. Patients with the above-listed cardiovascular co-morbidities also had an increased rate of admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), utilization of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or death. Hence, patients with pre-existing CVD and CV risk factors appear to develop a worse disease outcome [3]. Information regarding the impact of patients' comorbidities, including CVD and HTN, on COVID-19 outcomes is limited.

In this article, we carried out a pooled analysis of existing observational studies to identify the prevalence of CVD and HTN and outcomes in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing CVD and HTN.

Materials and methods

Endpoints

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the association between outcomes of COVID-19 patients with pre-existing CVD and HTN. The secondary aim of this study was to identify the pooled prevalence of CVD and HTN among COVID-19 hospitalized patients. We have considered all-cause in-hospital mortality and mechanical ventilation utilization as our outcomes. Pre-existing CVD is defined as a history of coronary artery disease, history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, and heart failure. A composite poor outcome was defined by ICU admission, oxygen saturation (SpO2) <90%, IMV utilization, severe disease and in-hospital mortality. Severe disease was defined by respiratory distress, respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min with SpO2 ≤93% at rest, PaO2/FIO2 ≤300, patients with >50% lung lesion progression within 24 to 48 hours, and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, shock, and organ failure requiring ICU treatment.

Search strategy and selection criteria

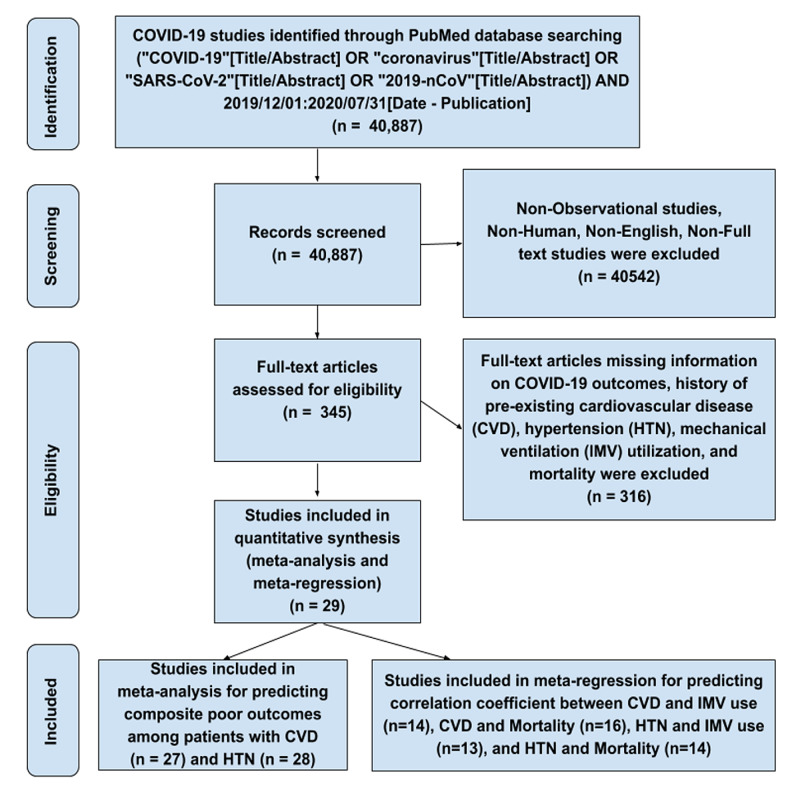

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed using Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in EpidemiologyMeta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol. We searched PubMed for observational studies that described characteristics of COVID-19 from December 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020, following query: ("COVID-19"[Title/Abstract] OR "coronavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "SARS-CoV-2"[Title/Abstract] OR "2019-nCoV"[Title/Abstract]) AND 2019/12/01:2020/07/31[Date - Publication]. Studies describing the epidemiology of COVID-19 were included. Literature other than observational studies, non-English literature, non-full text, and animal studies were excluded. A flow diagram of literature search and study selection process is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram describing the study selection process.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation

Study selection

Abstracts and full-length articles were reviewed for availability of data on outcomes and pre-existing CVD and HTN as comorbidity for quantitative analysis. CS, JR, MM, and TO screened all identified studies and assessed full-texts to decide eligibility. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with other reviewers (NK and HS).

Data collection

From the included studies, data relating to patient age and history of HTN and CVD were gathered on collection forms by three authors (CN, PR, SY), with a common consensus of two authors (KL, AY) upon disagreement. Details on outcomes such as mortality and needs for IMV were collected using pre-specified data collection templates. The study characteristics like publication year, country of origin, and sample size, study design, mean age of patients, and type of adverse outcomes are described in Table 1, with included studies and study data collected as a part of Malik et al.'s work and following similar methods and definition of adverse outcomes [9].

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies considered for the review.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HTN, hypertension

*Definition of pre-existing CVD was not specified in most of the studies, but mainly covered coronary artery disease, history of percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, and heart failure.

aSevere disease is defined by respiratory distress, respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min with SpO2 ≤93% at rest, PaO2/FIO2 ≤300, patients with >50% lesion progression within 24 to 48 hours, and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, shock, and other organ failure requiring ICU treatment.

| Study | Country | Sample size (n) | Study design | Mean age (years) | Adverse outcomes | Pre-existing CVD* and HTN |

| Huang et al., 2020 | China | 41 | Prospective single-center | 49 | ICU admission | Pre-existing CVD (afibrillation) and HTN |

| Guan et al., 2020 | China | 1099 | Retrospective multi-center | 47 | ICU admission/mechanical ventilation/death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Zheng et al., 2020 | China | 34 | Retrospective single-center | 66 | Invasive mechanical ventilation | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Wang et al., 2020 | China | 138 | Retrospective single-center | 56 | ICU admission | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Chen et al., 2020 | China | 21 | Retrospective single-center | 56 | Severe diseasea | HTN |

| Hong et al., 2020 | South Korea | 98 | Retrospective single-center | 55 | ICU admission | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Wang et al., 2020 | China | 69 | Retrospective single-center | 42 | SpO2<90% | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Mo et al., 2020 | China | 155 | Retrospective single-center | 54 | Refractory pneumonia | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Wu et al., 2020 | China | 201 | Retrospective single-center | 51 | ARDS | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Zhou et al., 2020 | China | 191 | Retrospective multi-center | 56 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Wang et al., 2020 | China | 339 | Retrospective single-center | 69 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Huang et al., 2020 | China | 202 | Retrospective multi-center | 44 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Colaneri et al., 2020 | Italy | 44 | Retrospective single-center | 67 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Goyal et al., 2020 | USA | 393 | Retrospective multi-center | 62.2 | Invasive mechanical ventilation | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Ruan et al., 2020 | China | 150 | Retrospective multi-center | 58.5 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Du R et al., 2020 | China | 179 | Prospective single-center | 57.6 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Qin et al., 2020 | China | 452 | Retrospective single-center | 58 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Paranjpe et al., 2020 | USA | 2199 | Retrospective single-center | 65 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Zheng et al., 2020 | China | 161 | Retrospective single-center | 45 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | China | 663 | Retrospective single-center | 55.6 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Mikami et al., 2020 | USA | 6493 | Retrospective multi-center | 59 | Death | HTN |

| Marcello et al., 2020 | USA | 13442 | Retrospective multi-center | 52.7 | Death | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Wang et al., 2020 | China | 275 | Retrospective single-center | 49 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Cao et al., 2020 | China | 80 | Retrospective single-center | 53 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Shahriarirad et al., 2020 | Iran | 113 | Retrospective multi-center | 53.75 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Suleyman et al., 2020 | USA | 463 | Prospective multi-center | 57.5 | ICU admission | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Khamis et al., 2020 | Oman | 63 | Retrospective multi-center | 48 | ICU admission | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | China | 140 | Retrospective single-center | 57 | Severe diseasea | Pre-existing CVD and HTN |

| Yang et al., 2020 | China | 52 | Retrospective single-center | 59.7 | Death | Pre-existing CVD |

| Total studies = 29 | Total, n=27,950 |

Statistical analysis

The pooled prevalences of pre-existing CVD and HTN were calculated. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (Cochrane RevMan 5; Cochrane, London), and Maentel-Haenszel random-effects models were used to pool odds ratio (OR), 95%CI, p-value, and heterogeneity (I²) to evaluate the relationship between both comorbidities and composite poor outcomes/severe disease of COVID-19 patients in each study. The forest plots were created.

Age-adjusted meta-regression was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ) used estimated correlation coefficient (r), odds ratios [e^ coefficient], 95% CI, p-value, and I2 between these comorbidities and IMV utilization and mortality. The correlation plots were created using random-effects models. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant and I² >75% was considered significant heterogeneity.

Results

Review of the databases identified 40,887 articles, out of which 345 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility using inclusion and exclusion criteria. During the second round, we excluded 316 articles with insufficient clinical information on COVID-19 outcomes. A total of 29 articles on COVID-19 and outcomes due to pre-existing CVD and HTN were extracted for final evaluation. After detailed assessment, as of July 31, 2020, we included 27 articles for meta-analysis for predicting composite poor outcomes among patients with CVD and 28 articles for HTN. For meta-regression to predict the correlation between CVD and IMV use, CVD and mortality, HTN and IMV use, and HTN and mortality, we considered 14, 16, 13 and 14 articles, respectively.

Pooled prevalence of CVD and HTN

The pooled prevalence of pre-existing CVD was 18.2% (2144/11,775 patients) and for HTN was 32.7% (4572/13,966 patients) amongst COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Meta-analysis showing prediction between composite poor outcomes (severe disease) and comorbidities (CVD and HTN)

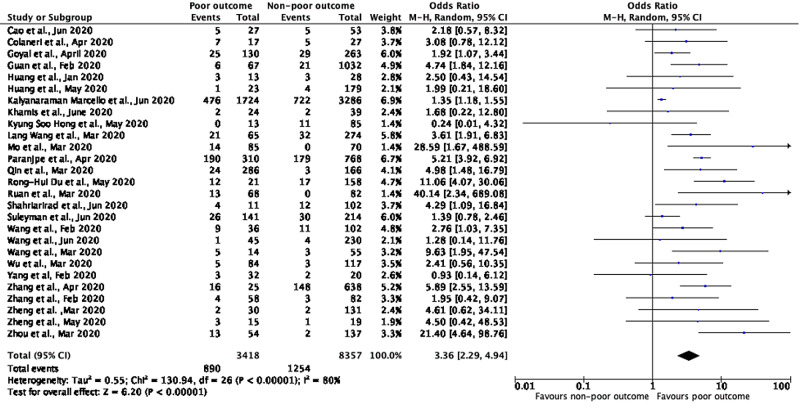

A meta-analysis of 27 studies having details on CVD showed that patients with poor outcomes (severe disease) had higher odds of having pre-existing CVD compared to non-severe disease with a pooled OR of 3.36 (95% CI: 2.29-4.94; p<0.00001), with a significant between-study heterogeneity (p=0.00001; I²=80%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis showing prediction between composite poor outcomes and cardiovascular disease.

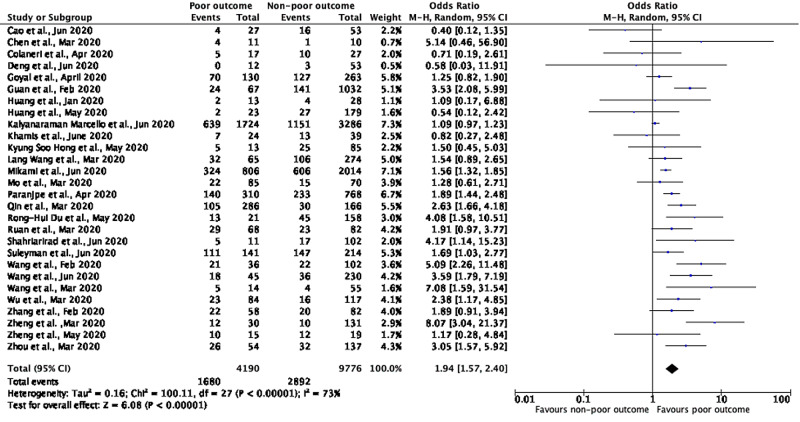

A meta-analysis of 27 studies having details on HTN showed that patients with poor outcomes/severe disease had higher odds of having pre-existing HTN compared to non-severe disease with a pooled OR of 1.94 (95% CI: 1.57-2.40; p<0.00001), with a significant between-study heterogeneity (p=0.00001; I²=73%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis showing prediction between composite poor outcomes and hypertension.

Meta-regression showing correlation of pre-existing CVD with IMV utilization and mortality

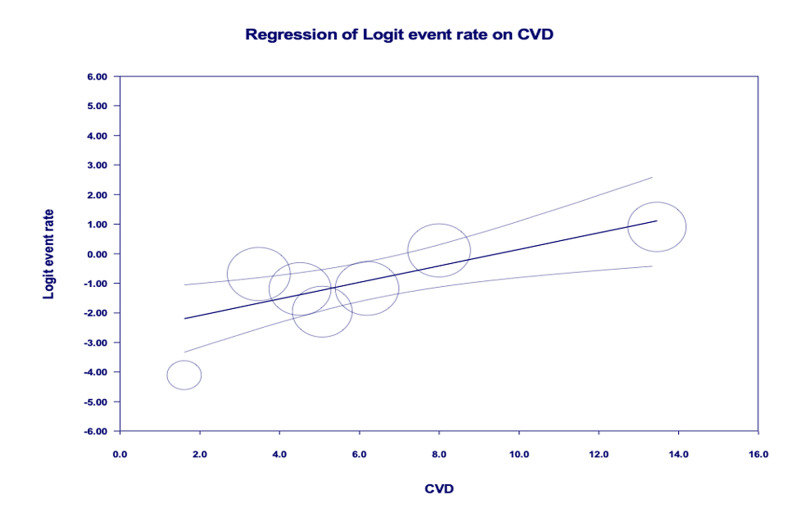

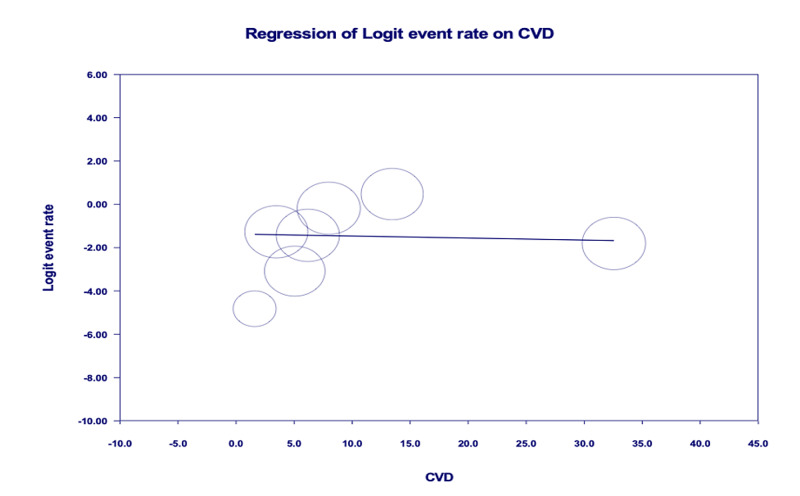

Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis showed IMV utilization was significantly higher among COVID-19 patients with pre-existing CVD [r: 0.28; OR: 1.3 (1.1-1.6); I2: 89.7%; p=0.0028] (Figure 4). There was no significant correlation between pre-existing CVD and mortality [r: -0.01; OR: 0.9 (0.9-1.1); I2: 96.3%; p=0.8772] (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis for the evaluation of need for invasive mechanical ventilation amongst patients with CVD.

CVD, cardiovascular disease

Figure 5. Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis for evaluation of mortality amongst patients with patients with CVD.

CVD, cardiovascular disease

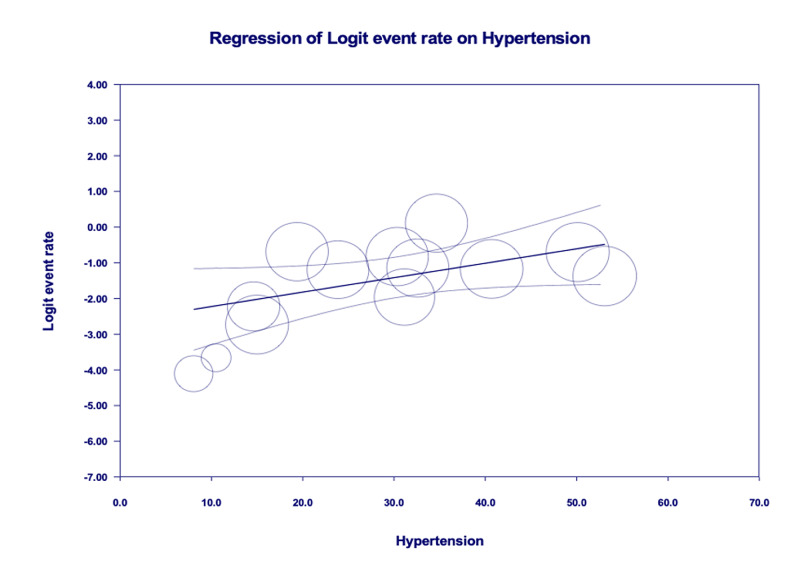

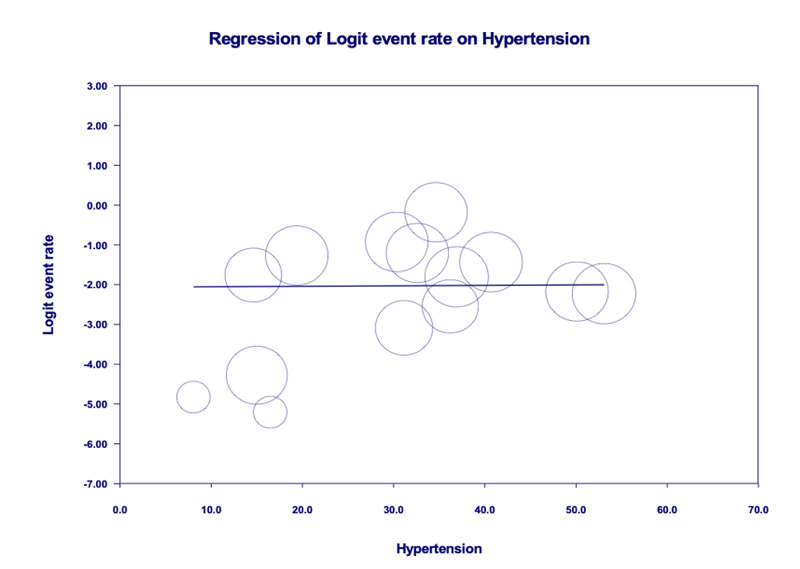

Meta-regression showing correlation of pre-existing HTN with IMV utilization and mortality

Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis showed HTN was neither significantly correlated with IMV utilization [r: 0.01; OR: 1.0 (0.9-1.1); I2: 95.9%; p=0.8161] (Figure 6) nor correlated with increased mortality [r: 0.001; OR: 1.0 (0.9-1.1); I2: 96%; p=0.9685] amongst COVID-19 patients (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis for the evaluation of need for invasive mechanical ventilation amongst patients with hypertension.

Figure 7. Age-adjusted meta-regression analysis for the evaluation of mortality amongst patients with hypertension.

Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and has shown that studies included in this meta-analysis have moderate to high risk of bias (Table 2).

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| Study | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Overall risk of bias | ||

| Selection | Comparability | Exposure | ||

| Huang et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Low |

| Guan et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Zheng et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Wang et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Chen et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Hong et al., 2020 | ** | * | ** | High |

| Wang et al., 2020 | ** | * | ** | High |

| Mo et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Wu et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Zhou et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Moderate |

| Wang et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Huang et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Colaneri et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Goyal et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Ruan et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Rong-Hui Du et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Qin et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Paranjpe et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Zheng et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Moderate |

| Mikami et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Marcello et al., 2020 | *** | * | ** | Moderate |

| Wang et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Cao et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Shahriarirad et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Moderate |

| Suleyman et al., 2020 | ** | * | * | High |

| Khamis et al., 2020 | **** | * | * | Low |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Moderate |

| Yang et al., 2020 | *** | * | * | Moderate |

Discussion

The included studies have shown that vascular risk factors like pre-existing CVD, HTN, cerebrovascular disease, obesity, smoking, and diabetes were highly prevalent [10] and also associated with severe COVID-19 [11-15]. In our study, the prevalence of CVD is 18.2% and HTN is 32.7%. According to Matsushita et al., age is an independent risk factor for the severity [16], so we have adjusted our models for the age before predicting the disease severity. Our meta-regression showed patients with pre-existing CVD had higher odds of composite poor outcome (OR: 3.36) and age-adjusted meta-regression analysis showed pre-existing CVD had higher odds of need for IMV by 30% without significant relationship with high mortality. A very early report of 44,672 confirmed cases from China showed that the case-fatality rate was higher amongst pre-existing CVD, HTN (10.5% vs 6.0%) cases compared to overall case-fatality rate (2.3%) [17].

Potential mechanisms of myocardial injury in COVID-19 include hypoxia-induced myocyte damage and an immune-mediated cytokine storm. We know that SARS-CoV-2 tends to bind to the ACE2 expressed in the epithelial linings of the lungs, causing the COVID-19 disease. Since hypertensive patients are treated with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, there has been a concern if the SARS-CoV-2 has any significant poor outcomes in such patients [5,18,19]. Patients with pre-existing CVD have a higher risk of developing acute cardiac injury and other cardiovascular complications. At regular intervals, cardiac troponin I and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) serve as important biomarkers that help to stratify patients according to their risk of cardiac injury and outcomes in hospitalized patients [20,21].

Our meta-analysis showed that COVID-19 patients with pre-existing HTN have poor outcomes. This was consistent with the retrospective study conducted in China where after adjusting for age and smoking status, hypertensive patients were more likely to reach the composite end-points (ICU admission, IMV utilization, or death) as compared to non-hypertensive patients with a hazard ratio of 1.58 [22]. One study showed that the OR of death is greater than 1 in patients with HTN with the greatest OR of 3.5 in patients with heart disease [23]. While as per our study, there is no significant association between HTN and mortality, Pranata et al. and Lippi et al. demonstrated that there is a higher risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients with HTN [12,24]. It was noted that there is no significant association of HTN with mortality and IMV utilization. Similar findings were inferred by a study in New York City including 5700 patients [25]. The discrepancy between other study findings and our meta-analysis results is explained by bigger sample size (n=27,950) pooled from 29 studies all over the world, high power, and performing age-adjusted analysis.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the one of the large meta-analyses showing meta-regression of 29 studies (USA and non-USA) that tried to demonstrate the association of HTN and pre-existing CVD with poor outcomes (ICU admisssions, needs for mechanical ventilator, or death). Our study has high heterogeneity. Studies are also missing details on the severity of these risk factors. We have not adjusted our results with others comorbidities and confounders. The long-term follow-up was missing amongst studies we have chosen for our analysis.

Conclusions

Our findings may provide insights into designing models for the early identification of high-risk patients and prioritizing their treatment based on disease severity. More prospective studies should be planned to evaluate the role of concurrent comorbidities with CVD and HTN and composite effects of these comorbidities on outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

R.C. and C.S. contributed equally.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update. [Dec;2021 ];https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Coronavirus Dis. 2020

- 3.Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phylogenetic analysis and structural modeling of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reveals an evolutionary distinct and proteolytically sensitive activation loop. Jaimes JA, André NM, Chappie JS, Millet JK, Whittaker GR. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:3309–3325. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COVID-19 and heart failure: from infection to inflammation and angiotensin II stimulation. Searching for evidence from a new disease. Tomasoni D, Italia L, Adamo M, Inciardi RM, Lombardi CM, Solomon SD, Metra M. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:957–966. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, et al. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Inciardi RM, Adamo M, Lupi L, et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The cardiovascular burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with a focus on congenital heart disease. Tan W, Aboulhosn J. Int J Cardiol. 2020;309:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biomarkers and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalisations: systematic review and meta-analysis (online ahead of print) Malik P, Patel U, Mehta D, et al. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Early epidemiological indicators, outcomes, and interventions of COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Patel U, Malik P, Mehta D, et al. J Glob Health. 2020;10:20506. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obesity a predictor of outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malik P, Patel U, Patel K, et al. J Med Virol. 2020;93:1188–1193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Impact of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases on mortality and severity of COVID-19-systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA, Wahjoepramono EJ, July J. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104949. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pre-existing cerebrovascular disease and poor outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis. Patel U, Malik P, Shah D, Patel A, Dhamoon M, Jani V. J Neurol. 2020;268:240–247. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10141-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Is there a smoker’s paradox in COVID-19? (Online ahead of print) Usman MS, Siddiqi TJ, Khan MS, et al. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Age-adjusted risk factors associated with mortality and mechanical ventilation utilization amongst COVID-19 hospitalizations—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patel U, Malik P, Usman MS, et al. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2:1740–1749. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00476-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The relationship of COVID-19 severity with cardiovascular disease and its traditional risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matsushita K, Ding N, Kou M, et al. Glob Heart. 2020;15:64. doi: 10.5334/gh.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Watanabe Y, Allen JD, Wrapp D, McLellan JS, Crispin M. Science. 2020;369:330–333. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Association of inpatient use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, et al. Circ Res. 2020;126:1671–1681. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elevated cardiac troponin I as a predictor of outcomes in COVID-19 hospitalizations: a meta-analysis. Malik P, Patel U, Patel NH, Somi S, Singh J. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33257623/ Infez Med. 2020;28:500–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19. Gao L, Jiang D, Wen XS, et al. Respir Res. 2020;21:83. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01352-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comorbidity and its impact on 1,590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, et al. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical determinants of the severity of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matsuyama R, Nishiura H, Kutsuna S, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1203. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hypertension in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Lippi G, Wong J, Henry BM. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130:304–309. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]