Abstract

Enzymes typically have high specificity for their substrates, but the structures of substrates and products differ, and multiple modes of binding are observed. In this study, high resolution X-ray crystallography of complexes with NADH and alcohols show alternative modes of binding in the active site. Enzyme crystallized with the good substrates NAD+ and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol was found to be an abortive complex of NADH with 4-methylbenzyl alcohol rotated to a “non-productive” mode as compared to the structures that resemble reactive Michaelis complexes with NAD+ and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol or 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol. The NADH is formed by reduction of the NAD+ with the alcohol during the crystallization. The same structure was also formed by directly crystallizing the enzyme with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol. Crystals prepared with NAD+ and 4-bromobenzyl alcohol also form the abortive complex with NADH. Surprisingly, crystals prepared with NAD+ and the strong inhibitor 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol also had NADH, and the alcohol was bound in two different conformations that illustrate binding flexibility. Oxidation of 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol during the crystallization apparently led to reduction of the NAD+. Kinetic studies show that high concentrations of alcohols can bind to the enzyme-NADH complex and activate or inhibit the enzyme. Together with previous studies on complexes with NADH and formamide analogues of the carbonyl substrates, models for the Michaelis complexes with NAD+-alcohol and NADH-aldehyde are proposed.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography; hydrogen transfer; 4-methylbenzyl alcohol; 4-bromobenzyl alcohol; 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol

1. Introduction

Horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase catalyzes the oxidation of many primary and secondary alcohols with NAD+ and reduction of the product aldehydes and ketones with NADH. Structures of many complexes show that the binding site for the substrates is a hydrophobic barrel that accommodates non-polar compounds [1, 2]. Several structures show that substrate analogues (inhibitors) can bind in different modes and that the enzyme is flexible and adapts to binding different ligands. An objective of this study was to determine a high resolution structure of an active enzyme-substrate complex, in order to describe further species in the enzyme mechanism. High resolution structures of apoenzyme, complexes with NAD+ and fluoroalcohols, or with NADH, or with NADH and inhibitors that mimic carbonyl substrates have been determined [3–11]. However, atomic resolution structures of complexes with NAD+ alone, or NAD+ and a reactive alcohol, or NADH and a reactive carbonyl compound have not been determined.

In the first study of a structure of an enzyme-substrate complex (2.9 Å resolution), it appeared that 4-bromobenzyl alcohol was bound in a “non-productive” position that could transfer the pro-R methylene hydrogen to C4N of the nicotinamide ring of NAD after a small rotation about single bonds, presumably with a low energy barrier [12]. Subsequently, a higher resolution structure (2.1 Å, 1HLD.pdb) of a complex with NAD+ and 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol (an unreactive inhibitor), showed such a “productive” binding mode where the pro-R hydrogen is directed toward C4N, and the different position of 4-bromobenzyl alcohol was confirmed [13]. NMR shows that flipping of the benzene ring of pentafluorobenzyl alcohol is relatively restricted, whereas NMR and X-ray crystallography (1.8 Å) show that 2,3-difluorobenzyl alcohol binds in two alternative positions related by a ring flip and a small translation (1MG0.pdb) [7]. In contrast, 2,3-difluorobenzyl alcohol and 2,4-difluorobenzyl alcohol bind in only one position in the complex of the enzyme with the H51Q:K228R substitutions (1.8 Å, 1QV6.pdb and 1QV7.pdb) [14]. In all of these crystal structures, the identity of the coenzyme, NAD+ or NADH, was not established. Atomic resolution structures (1.1 Å, 4DWV.pdb and 4DXH.pdb) finally showed that complexes with 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol or 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol had NAD+ with strained nicotinamide rings [10].

Meanwhile, structures were determined with NADH and potent inhibitors that mimic carbonyl substrates and have an oxygen that binds directly to the catalytic zinc. The 1S,3R and 1S,3S isomers of 3-butylthiolane 1-oxide bind with the butyl groups extending into different positions in the substrate binding site (1BTO.pdb and 3BTO.pdb) [4]. (R)-N-1-Methylhexylformamide binds in one conformation to the enzyme-NADH complex (1P1R.pdb), but both isomers in the racemic (R,S) mixture also bind, with the butyl tail (C4-C7) in different positions (5VN1.pdb) [8, 11].

In the present study, high resolution structures were determined of ternary complexes with coenzyme and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (1.20 Å resolution), 4-bromobenzyl alcohol (1.53 Å), and 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol (1.55 Å). The crystals are in the P21 space group with 2 dimeric molecules (4 independent subunits), which provides good estimates of the geometries in the active site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

LiNAD and Na2NADH were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. The substituted benzyl alcohols and 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol were purchased from Aldrich. 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) was obtained from Kodak and treated with activated charcoal before use to remove contaminating aldehydes that react with the protein. Crystalline horse liver ADH1E (Equus caballus, NCBI taxonomy ID 9796, UniProt Entry P00327, GenBank accession number M64864, isoenzyme 1E active on ethanol) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals.

2.2. Crystallization

Crystals were prepared by batch dialysis [10, 13]. The enzyme was first recrystallized by dialysis at 5 °C in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, with 10% ethanol, and the crystals were redissolved in 50 mM ammonium N-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-2-aminomethanesulfonate and 0.25 mM EDTA buffer (pH 7.0, pH 6.7 at 25 °C) and dialyzed extensively. The enzyme concentration was adjusted to 10 mg/ml (A280 = 4.55/cm), and 0.5–1.0 ml was placed in washed ¼ in. diameter dialysis tubing and put into 10 ml of the buffer, to which coenzymes and ligands were added. Crystallization at 5 °C was initiated by adding 1.1 ml 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), and the concentration of MPD was further increased over some days to about 14%, when crystals formed, and was slowly raised to a final concentration of 25%, which is sufficient for cryoprotection at 100 K.

Two complexes were prepared with reacting substrates, 1 mM NAD+ and 10 mM 4-methylbenzyl alcohol or 1 mM NAD+ and 10 mM 4-bromobenzyl alcohol. After 2 months, the UV spectrum of the outer dialysate of the crystals with 4-methylbenzyl alcohol showed that the concentration of NAD+ was 0.92 mM and that no NADH was detectible. After another month the crystals were mounted on fiber loops (Hampton Research) and flash vitrified by plunging them into liquid nitrogen. Crystals for the “abortive complex” with 1 mM NADH and 10 mM 4-methylbenzyl alcohol were prepared by the same procedure. After 2 months, the UV spectrum of the outer dialysate showed that 0.32 mM NADH and 0.48 mM NAD+ were present. A complex was also prepared with 1 mM NAD+ and 4.0 mM 1H-1H-heptafluorobutanol, an unreactive inhibitor (Ki = 5 μM at pH 8) [15].

2.3. X-ray crystallography

The data for the crystal prepared with NAD+ and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol were collected on July 7, 2006, at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratories on the GM/CA 23-ID-D beamline with wavelength of 0.9537 Å at 100 K with a crystal to detector (MAR300) distance of 120 mm, with 0.25° oscillations over 360° total, with 4 s exposures for a high resolution pass, and at 200 mm with 0.5° oscillations over 360° total, with 1 s exposures for a low resolution pass. The data for the enzyme prepared with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol were collected in the same manner, except that a total rotation of 180° was used for the high and low resolution passes.

The data for the complex with NAD+ and 4-bromobenzyl alcohol were collected April 23 to 29, 2004, at 100 K with a wavelength of 1.5418 Å on The University of Iowa R-Axis IV++ instrument with a rotating anode and image plate with 3 min exposures, 0.25° oscillations at 150 mm and 2θ = 0° for 201° total rotation, and then 5 min exposures at 2θ = −12.7° with 0.25° oscillations at 140 mm for 245° total rotation.

The data for the complex with NAD+ and 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol were collected April 12 to 16, 2004, at 100 K with a wavelength of 1.5418 Å on The University of Iowa R-Axis IV++ with 3 min exposures, 0.5° oscillations at 150 mm and 2 θ = 0° for 180° total rotation, and 2 θ = – 12.5° with 0.25° oscillations at 140 mm for 210° total rotation.

Data were processed with d*TREK [16]. The structures were solved by molecular replacement with the isomorphous wild-type enzyme (5VL0.pdb or 4DWV.pdb) and refined with REFMAC [17, 18]. The ligands were removed and the dictionary for NAD was modified to relax the restraints on bond angles and distances so that the geometry of the nicotinamide ring in the complex could be fitted as either NAD+ or NADH [10, 19]. After it was established that all of the structures had NADH, refinement continued with a modified dictionary for NAI with relaxed restraints on the nicotinamide ring [11]. Riding hydrogens were added, and anisotropic displacement parameters were refined. After each refinement cycle, the models were rebuilt manually using the program “O” using 2|Fo| – |Fc| and |Fo| – |Fc| difference maps [20]. Several residues were modeled with alternative conformations where indicated by electron density. Water molecules were included if the electron density was well-formed, B-factors were less than about 50 Å2, and hydrogen bonds connected the waters to the protein.

After refinement with REFMAC of the two atomic resolution structures with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol, SHELXL-2013 [21] was used for one full-matrix cycle of least-squares refinement (L.S. 1, BLOC 1) in order to calculate puckering angles for the nicotinamide rings.

The quality of the refinement was monitored with PROCHECK and SFCHECK [17], MolProbity [22] and PARVATI [23]. Figures were made with the Molray web interface server in Uppsala, Sweden [24].

3. Results

3.1. Structures of the Enzyme Complexes

Atomic resolution data provided three-dimensional structures of the complexes of the wild-type enzyme with NADH and the substrate analogues (Table 1). The structures were well-determined as shown with the statistics and the electron density maps. The four subunits of ADH in the asymmetric unit are crystallographically independent, but they have very similar structures. The multiple determinations of active site geometry provide good estimates of bond distances and angles.

Table 1.

X-ray data and refinement statistics for complexes of liver alcohol dehydrogenase.a

| Coenzyme/Alcohol | NADH/VTG | NADH/MBZ | NADH/BRB | NADH/B7F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB entry name | 7K35 | ~7K35b | 7JQA | 6XT2 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | 50.2, 180.2, 86.9 | 50.3, 180.3, 87.0 | 50.0, 180.1, 86.7 | 50.2, 180.3, 86.9 |

| Cell angles (deg) | 90.0, 106.1, 90.0 | 90.0, 106.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 106.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 105.8, 90.0 |

| Mosaicity | 1.03 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.78 |

| Resolution range (Å), (outer shell) | 19.90–1.20 (1.24–1.20) | 19.97–1.20 (1.24–1.20) | 19.91–1.53 (1.57–1.53) | 19.92–1.55 (1.61–1.55) |

| No. of reflections (total, unique) | 4347329, 453921 | 1845237, 391326 | 907262, 168958 | 1064949, 187028 |

| Redundancy (outer shell) | 9.53 (7.20) | 4.67 (3.33) | 5.32 (2.26) | 5.64 (2.62) |

| Completeness (outer shell) (%) | 99.2 (98.2) | 85.7 (56.7) | 77.2 (56.6) | 88.3 (76.3) |

| Rpim (outer shell) (%)c | 3.9 (23.9) | 4.3 (33.0) | 3.1 (28.3) | 2.3 (21.9) |

| Mean <I>σ<I> (outer shell) | 7.1 (1.8) | 9.2 (2.2) | 15.4 (2.7) | 30.7 (3.1) |

| Rvalue, Rfree (%) (test %, number)d | 17.7, 21.0 (0.5, 2399) | 17.1, 20.8 (1.0, 4032) | 14.9, 22.1 (1.0, 1693) | 13.8, 19.2 (0.9, 1769) |

| RMSD for bond distances (Å), angles (deg)e | 0.017, 2.13 | 0.014, 1.99 | 0.012, 1.90 | 0.016, 1.98 |

| Estimated errors in coordinates (Å) | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.068 | 0.055 |

| B-factor, Wilson (Å2) | 15.8 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 17.2 |

| Non H atoms fitted, total (B-factors)f | 12848 (23.9) | 12888 (19.3) | 12473 (21.4) | 12843 (20.9) |

| protein with alternative positions | 11347 (24.8) | 11365 (19.8) | 11206 (22.4) | 11356 (21.7) |

| 8 Zn, 4 NADH, 4 alcohols, MPDs | 236 (23.2) | 236 (18.1) | 228 (20.3) | 296 (21.5) |

| waters, with alternative positions | 1265 (34.1) | 1287 (30.4) | 1039 (30.8) | 1238 (31.4) |

| Ramachandran, favored, outliers (%) | 96.8, 0 | 97.7, 0 | 96.2. 0 | 96.4, 0 |

| MolProbity (clash, score, rank) | 1.28, 98th, 1.05, 98th | 1.36, 98th; 1.01, 99th | 1.65, 99th, 1.10, 99th | 1.91. 99th; 1.23, 97th |

| Matthews coefficient, fraction solvent | 2.24, 0.45 | 2.25, 0.45 | 2.23, 0.45 | 2.24, 0.45 |

The space groups are P21, with two homodimeric molecules each with 748 amino acid residues in the asymmetric unit. Ligands are 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (YTG in the PDB file or MBZ); BRB, 4-bromobenzyl alcohol; and 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol (B7F in the PDB).

Refinement statistics for enzyme crystallized with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol as the abortive complex. The structure is essentially identical to the complex deposited as 7K35.

Rpim, redundancy independent merging, = Rmerge/(n − 1)1/2 merge , where n is data redundancy.

Rvalue = (Σ|Fo − kFc|)/Σ|Fo|, where k is a scale factor. Rfree was calculated with the indicated percentage of reflections not used in the refinement [25].

Root-mean-square deviations from ideal geometry.

The number of atoms and the B-factors (in parentheses) in the following three rows were calculated with the PARVATI server [23].

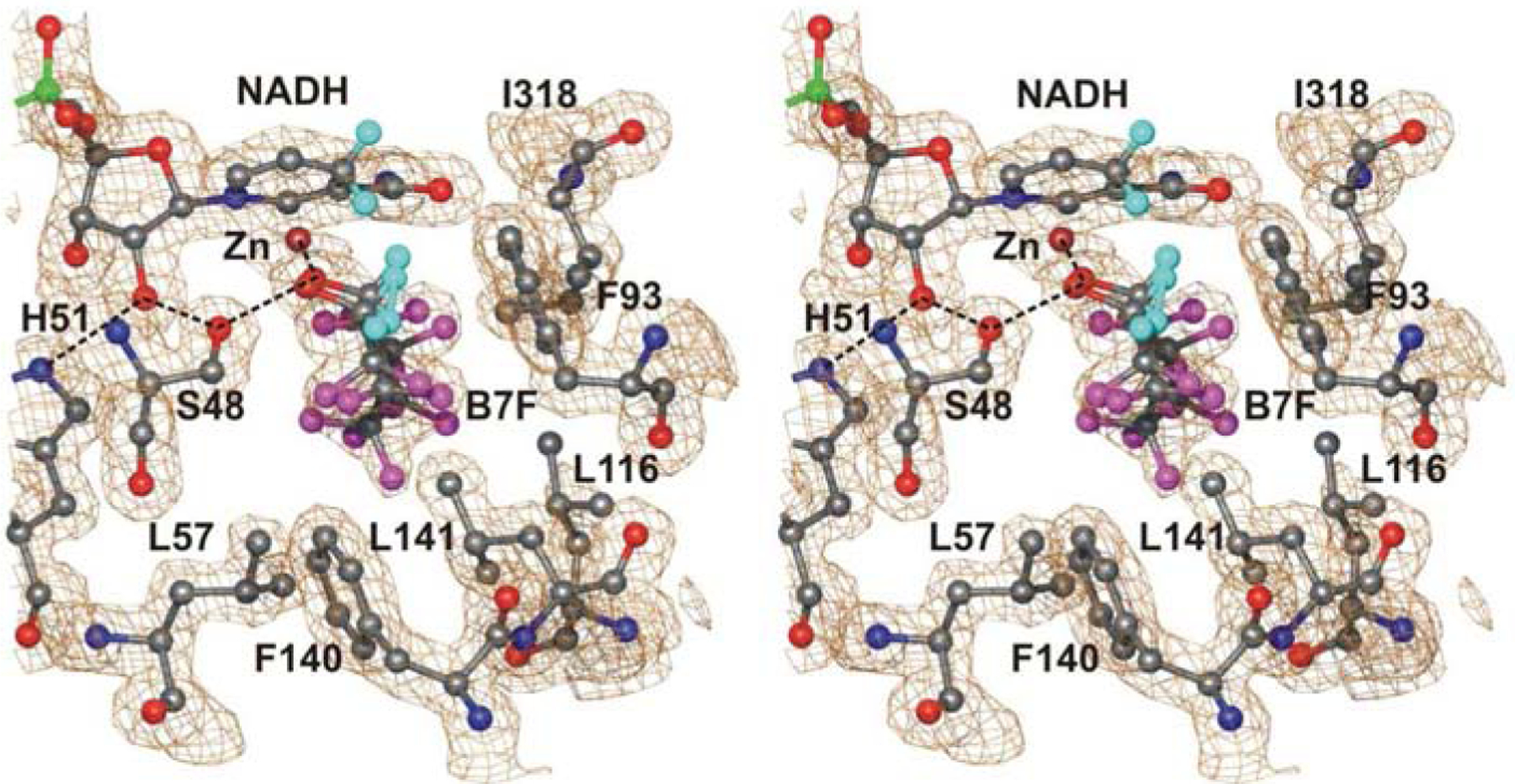

The structure of one active site of the complex produced by crystallization with NAD+ and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol is presented in Fig. 1. The positions of the coenzyme and alcohol are very well defined, and the geometry might resemble a Michaelis complex. However, it is clear that the complex is actually an abortive complex with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol. The nicotinamide ring is puckered, as defined by angles between planes α-C4 (C3-C4-C5 versus C2-C3-C6) of 23 ± 4 deg and α-N1 (C2-N1-C6 versus C2-C3-C6) of 5 ± 4 deg, with no significant twist, values that are consistent with several structures of complexes of ADH1E with NADH, but not with those with NAD+ [10, 11, 26]. The ring puckering clearly differs from that in the atomic resolution structure of the complex with NAD+ and 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol, which has a very similar protein structure, but where the benzene rings are shifted somewhat (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the active site of the B subunit of the abortive complex with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (7K35.pdb). The electron density map is contoured at ~0.7 e−/Å3. The coordination of the alcohol oxygen to the catalytic zinc and the hydrogen bond system connecting to His-51 are indicated with the dotted lines.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the active sites of enzyme complexed with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (MBZ, 7K35.pdb, green stick) and enzyme with NAD+ and 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol (PFB, 4DWV.pdb, atom coloring, magenta for F). The side chain of Val-294 to the right of Ser-48 is not labeled. The benzene rings of the alcohols are coplanar and slightly rotated while maintaining the zinc-O1 coordination. Note that the reduced nicotinamide ring of NADH (green) is puckered.

Examination of the bond distances of the nicotinamide rings also confirms that the coenzyme is reduced in the complex with 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (Table 2). The structure of the complex produced by crystallization with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol is essentially identical to the one crystallized with NAD+ and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol, and therefore eight values were averaged. The bond distances for C3N-C4N and C4N-C5N in structures for enzymes with NADH are longer than those with enzymes crystallized with NAD+ and the strong inhibitors trifluoroethanol and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol. The NAD+ can be reduced by various alcohols during the months required for crystallization of the complexes.

Table 2.

Bond distances (Å ± S.D.) in the nicotinamide rings of NADH or NAD+ in ADH1E complexes.

| Complex | N1-C2 | C2-C3 | C3-C4 | C4-C5 | C5-C6 | C6-N1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH, VTGa | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 1.47 ± 0.03 | 1.50 ± 0.05 | 1.30 ± 0.04 | 1.43 ± 0.03 |

| NADH, BRBb | 1.35 ± 0.06 | 1.34 ± 0.06 | 1.53 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 1.34 ± 0.09 | 1.43 ± 0.05 |

| NADH, B7Fc | 1.37 ± 0.03 | 1.34 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.06 | 1.41 ± 0.04 | 1.32 ± 0.02 | 1.46 ± 0.04 |

| NADH, H2Od | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 1.50 ± 0.02 | 1.43 ± 0.02 | 1.44 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.02 |

| NADH, MHFe | 1.40 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 0.02 | 1.33 ± 0.03 | 1.42 ± 0.06 |

| NADH, BNFf | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 1.50 ± 0.03 | 1.42 ± 0.04 | 1.36 ± 0.05 | 1.42 ± 0.02 |

| NAD+-FALCg | 1.35 ± 0.01 | 1.36 ± 0.01 | 1.42 ± 0.01 | 1.38 ± 0.01 | 1.37 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.01 |

Average of eight subunits for two structures with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol from refinement with REFMAC with relaxed restraints on the nicotinamide rings (7K35.pdb).

Average of four subunits for the complex with 4-bromobenzyl alcohol (7JQA.pdb).

Average of four subunits for the complex with 1H,1H-heptafluorobutanol (6XT2.pdb).

Weighted average of the bond distances and errors for two subunits from refinement with SHELXL-2013 with no restraints on the nicotinamide ring (1.1 Å, 4XD2.pdb) [11].

Average of eight subunits from two structures (1.25 and 1.57 Å resolution) with N-1-methylhexylformamide (1P1R.pdb and 5VN1.pdb) [8, 11].

Average of four subunits for the complex with N-benzylformamide (1.24 Å, 5VL0.pdb) [11].

Weighted average for four subunits with SHELXL-2013 refinement with no restraints on the nicotinamide ring in complexes with NAD+ and the fluoroalcohols, pentafluorobenzyl alcohol and trifluoroethanol (1.1 Å, 4DWV.pdb and 4DXH.pdb) [27].

The NAD+ can be reduced by oxidation of 4-methylbenzyl alcohol, which is a very good substrate for horse liver ADH, as are other 4-substituted benzyl alcohols and benzaldehydes [28–30]. However, during the crystallization, it appears that the product, 4-methylbenzaldehyde dissociated from the enzyme and was replaced by the excess 4-methylbenzyl alcohol to form the abortive complex. The C–O bond distance of 1.42 Å and the C1-C7-O bond angle of 117° (Table 3) indicate that the ligand is the alcohol and not the aldehyde, which would have a C=O distance of 1.21 Å and a C1-C7=O angle of 124°.

Table 3.

Geometry of interacting atoms of the products and inhibitors in ADH complexes.a

| Ligand, PDB | C–O | X–C–O° | Zn–O | S48 OG–O | NAD C4N–C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTG, 7K35b | 1.42 ± 0.02 | 117 ± 3 | 2.18 ± 0.03 | 2.69 ± 0.05 | 3.97 ± 0.09 |

| BRB, 7JQA | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 109 ± 3 | 2.24 ± 0.04 | 2.58 ± 0.11 | 3.98 ± 0.16 |

| B7F, 6XT2c | 1.45 ± 0.03 | 115 ± 3 | 2.10 ± 0.03 | 2.54 ± 0.07 | 3.42 ± 0.13 |

| BNF, 5VLOd | 1.24 ± 0.01 | 135 ± 2 | 2.09 ± 0.02 | 2.70 ± 0.04 | 3.50 ± 0.04 |

| MHF, 5VN1d | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 126 ± 2 | 2.15 ± 0.03 | 2.70 ± 0.03 | 3.56 ± 0.05 |

| TFE, 4DXHe | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 115 ± 2 | 1.97 ± 0.01 | 2.47 ± 0.03 | 3.43 ± 0.04 |

| PFB, 4DWVe | 1.42 ± 0.02 | 113 ± 2 | 1.97 ± 0.01 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | 3.36 ± 0.04 |

Distances are in Å for average and standard deviation. “C” refers to the atom that could donate or receive the hydride. “O” is the oxygen of the alcohol or a formamide. “X” is N in formamides or C in alcohols. X–C–O angle is in degrees.

For eight subunits of the two structures with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol determined at 1.2 Å.

For four subunits for the complex with NADH and 1H,1H-heptafluorobenzyl alcohol determined at 1.55 Å. The values are averages of the two conformations.

For eight subunits of two structuress with NADH and N-benzylformamide or N-1-methylhexylformamide determined at 1.25 Å [11].

Table 3 also compares the ligand geometries for carbonyl compounds (formamides) and other alcohols in various complexes. The hydroxyl O of 4-methylbenzyl alcohol is ligated to the catalytic zinc with a bond distance of 2.2 Å and forms a hydrogen bond to the hydroxyl group of Ser-48 at 2.7 Å, which suggests that the hydroxyl group is not deprotonated to form the alkoxide. For comparison, the complexes with NAD+ and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol or 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl alcohol have a Zn–O distance of 2.0 Å, and the hydrogen bond to Ser-48 OG is 2.5 Å, consistent with a low-barrier hydrogen bond [10, 31, 32]. Kinetic studies suggest that he pK of water bound to the zinc decreases from 9.2 in free enzyme to 7.3 when NAD+ binds with its positively-charged nicotinamide ring nearby, whereas the pK of water is increased to 10.5–11.2 when NADH is bound [33–38]. In the complexes with NAD+ the pK of trifluoroethanol decreases to ~ 4.3 from 12.4 in solution, and the pK of ethanol decreases to ~ 6.4 from 15.9 in solution [39]. The formation of the zinc-alkoxide in the enzyme complex with NAD+ facilitates catalysis. After reduction to the aldehyde, as mimicked by the carbonyl oxygens of N-benzylformamide or N-1-methylhexylformamide in the complexes with NADH, the Zn–O distance probably increases to ~ 2.1 Å, and the hydrogen bond to Ser-48 OG increases to 2.7 Å, consistent with an uncharged oxygen.

The structural evidence shows that 4-methylbenzyl alcohol forms an abortive complex with NADH. The orientation of 4-methybenzyl alcohol in the active site is probably due to steric hindrance of the C7 methylene hydrogens with the C4N hydrogens of NADH (Fig. 3A). The distance between C7 and C4N is 4.0 Å (Table 3), and the pro-R hydrogen does not point directly to the nicotinamide ring. The orientation of this complex can be described as “non-productive.” In contrast, the complex with pentafluorobenzyl alcohol with NAD+ has a C7–C4N distance of 3.4 Å (Table 3), and the pro-R hydrogen points toward the re face of the nicotinamide ring in what can be described as a “productive” Michaelis complex (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Orientation of methylene hydrogens of 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (A) and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol (B) in complexes with NADH or NAD+, respectively. This is a stereo representation of the protein, and by using a stereo viewer and blinking one eye or the other, the different positions of the bound alcohol can be seen. Note that the pro-R hydrogen (cyan) of 4-methylbenzyl alcohol is not directed toward C4N of the nicotinamide (C7–C7H–C4N angle = 82°) whereas the pro-R hydrogen of pentafluorobenzyl alcohol is (C7–C7H–C4N angle = 128°). The angle for the pro-R hydrogen on C4N of NADH toward 4-methylbenzyl alcohol is more linear (C4N–C4NH–C7 angle = 165°).

The complex produced by crystallization of the enzyme with NAD+ and 4-bromobenzyl alcohol also contained NADH and the alcohol, and the structure is essentially superimposable on the one with 4-methylbenzyl alcohol. In the lower resolution structures with NADH and 4-bromobenzaldehyde determined earlier, it was not possible to define the oxidation states of the substrates, but the orientation of the benzyl group suggests that structure is also the abortive complex [12, 13]. We suggested that small rotations about single bonds of the benzyl alcohol could produce a reactive conformation. Now it is clear that the nicotinamide ring is reduced, as it is puckered and has bond distances that fit those with NADH determined at atomic resolution in other complexes (Table 2). Furthermore, the geometry of the 4-bromobenzyl alcohol and the interactions in the active site are essentially the same as those found for 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (Table 3). The alcohol is bound in a “nonproductive” orientation, and it appears 4-bromobenzyl alcohol reduced the NAD +, and the 4-bromobenzaldehyde was replaced by some remaining alcohol.

The first X-ray crystallography studies used the 4-bromo substituted substrate in order to locate the electron dense atom at low resolution [41]. In the present studies, it appears that the occupancy of the bromine is decreased, probably due to X-ray radiation, but that loss does not appear to affect the location of the benzene ring.

The structure of the complex with heptafluorobutanol and NAD+ was expected to be similar to the structures determined previously with trifluoroethanol and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol. However, refinement using a dictionary for NAD+ with relaxed restraints on the nicotinamide ring (“NAJ”), showed long bond distances and puckering of the ring, indicating that the nicotinamide ring is reduced (Table 2, Fig. 5). The final refinement used a dictionary for NADH with relaxed restraints (“NAI”) and confirmed the geometry. Heptafluorobutanol binds in a position that could resemble a Michaelis complex, but it appears that each of the four active sites has alternative conformations for the alcohol. The electron density maps were readily fit with one conformation in each of the four subunits, but B-factors were relatively high and divergent among the atoms. An alternative conformation also fit the density well, because the fluorine atoms on C2 in one conformation could rotate into almost the same positions as those on C3 of the other conformation (Fig. 6). Thus, both conformations were modeled into each active site and the occupancies were adjusted to be about 0.6/0.4 in subunits A, B, and C, and 0.8/0.2 in subunit D, so that the B-factors were similar. C1 and O1 of the alcohols are in similar positions for both conformations. The “A” conformation has C2 and its two attached fluorine atoms close to the nicotinamide ring, whereas the “B” conformation has C3 and its two fluorine atoms close to the nicotinamide ring. These positions overlap with the position of the pentafluorobenzene ring in the structures with pentafluorobenzyl alcohol (see Fig. 2). The average geometries represent structures for abortive enzyme-NADH-alcohol complexes (Table 3). However, the distances between C1 of the alcohol and C4N of the nicotinamide ring and the orientation of the pro-R hydrogen are somewhat uncertain, because of the alternative conformations, which nevertheless show the flexibility for binding of an alcohol. Although heptafluorobutanol should inhibit oxidation of the crystallizing alcohol, 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, or endogenous alcohols, it appears that the NAD+ is reduced during the ten month crystallization. Crystals were also produced using an amount of heptafluorobutanol that would produce 100 mM, but not all of the alcohol dissolved. Nevertheless, the data (to 1.6 Å resolution) also showed the puckered nicotinamide ring of NADH.

Fig. 5.

Structure of the A subunit of the abortive complex with NADH and 1H,1H-heptafluorobenzyl alcohol (B7F). The electron density map is contoured at ~0.7 e−/Å3. Atoms have the usual coloring, and fluorines are magenta and the hydrogens on the alcohols and NADH are in cyan.

Fig. 6.

The abortive complex with NADH and heptafluorobutanol is represented with the usual atomic coloring, with fluorines in magenta and hydrogens shown in cyan on the NADH and the alcohol. Note that the hydrogens are in close contact. The fluorines on C2 in one conformation overlap with those on C3 from the other conformation. The major conformation has the cyan stick connecting the hydrogens. The electron density map is contoured at ~1 e–/Å3 to highlight the positions of the fluorines.

4. Discussion

4.1. Formation of abortive complexes

When the enzyme-substrate complex formed by crystallizing ADH with NADH and 4-bromobenzaldehyde was prepared, we assumed that the reacting substrates would reach an equilibrium position that favored NAD+ and 4-bromobenzyl alcohol and that the on-enzyme equilibrium (E-NADH-aldehyde == E-NAD+-alcohol) would be about 10:1 in favor of the alcohol, based on transient kinetic studies [12, 41]. The kinetic data obtained later with benzyl alcohol/benzaldehyde indicated a ratio of 5:1 at pH 7 [31]. X-ray crystallography showed that 4-bromobenzyl alcohol binds in an orientation that was described as “nonproductive” because the pro-R hydrogen of the alcohol was not pointing directly toward C4N of the nicotinamide ring. The present high resolution studies show that the complexes with 4-methyl- and 4-bromo- benzyl alcohols actually are abortive complexes of the alcohol with NADH and not NAD+. In contrast, the atomic resolution studies of the complexes with NAD+ and the good inhibitors pentafluorobenzyl alcohol or trifluoroethanol, show the pro-R hydrogen pointing toward C4N of NAD+ with a strained nicotinamide ring [10].

The formation of NADH in these complexes can be explained by different mechanisms. Microspectrophotometry of crystals of complexes of ternary complexes made with NAD+ and fluoroalcohols showed that NADH was the major form of coenzyme, but the inhibitory fluoroalcohols were washed out with 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, which is a poor substrate and could reduce the NAD+ [42]. The reactive benzyl alcohols can also be oxidized to benzaldehydes, which can be further oxidized with NAD+ to the benzoic acids in a very slow, but irreversible, dismutation reaction that would produce more NADH and eventually produce an abortive enzyme-NADH-benzyl alcohol complex [12, 30]. Kinetic simulation of this complex reaction with the rate constants estimated for benzyl alcohol oxidation at pH 7 and 30 °C show that 85% of the enzyme could be converted to the abortive complex, with smaller concentrations of the enzyme-NAD+-alcohol and enzyme-NADH complexes, in 9 days. The rate constants would be somewhat different for the 4-bromo- and 4-methyl- benzyl alcohols at 5 °C, but the simulation can explain the crystallographic results. Although binding of the alcohol to the enzyme-NADH complex is estimated to be 10-weaker than to the enzyme-NAD+ complex, NADH binds 300-fold tighter than NAD+ does to the enzyme and drives the equilibrium.

The formation of the abortive complex with NADH and heptafluorobutanol can be explained by oxidation of methylpentanediol, which has a turnover number of about 0.045 s−1 (1.5% that of ethanol) and a Km of about 1 M [41]. Either stereoisomer of this secondary alcohol can be a substrate, but the resulting ketone is probably a poor substrate for the reverse reaction [26]. MPD also can also be found in the substrate binding site in the enzyme-NADH complex when other inhibitors are not present [6, 41]. Because heptafluorobutanol is a good inhibitor (Ki = 5 μM for binding to the enzyme-NAD+ complex) we expected that oxidation of MPD would be prevented, but the crystallography shows that complex contains NADH and heptafluorobutanol. If the reaction kinetics during crystallization are simulated with an assumed dissociation constant of 0.5 mM for the enzyme-NADH-heptafluorobutanol complex, 80% of the enzyme appears as the abortive complex, with smaller concentrations of the enzyme-NADH and enzyme-NAD+- heptafluorobutanol complexes, in 1 day. The simulations suggest that the concentration of heptafluorobutanol was not sufficient to prevent reduction of NAD+. In contrast, atomic resolution structures of complexes made with NAD+ and trifluoroethanol or pentafluorobenzyl alcohol, which are more potent inhibitors and were used at higher concentrations, contained oxidized nicotinamide rings [10, 26, 40, 43]. Nevertheless, the structures of the complex with heptafluorobutanol illustrate the flexibility of binding of ligands in the substrate binding site.

4.2. Multiple conformations in catalysis of hydrogen transfer

At this time, no structures of complexes of the enzyme with NAD+ alone, or NAD+ and a substrate, or NADH and a substrate are available. When the enzyme was crystallized with NAD+, the structure showed that NADH was present with a water bound to the catalytic zinc [11]. The structure was interesting because the catalytic zinc apparently has two positions, which is relevant for the mechanism of exchange of water and substrates ligated to the zinc. Structures for apoenzyme, complexes with NAD + and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol or trifluoroethanol, complexes with NADH alone and with formamides or sulfoxides have been determined. The structures of the ternary complexes show the flexibility of binding of ligands and provide a framework for understanding possible rearrangements involved in hydrogen transfer.

Structures with NAD+ and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol and with NADH and N-formylpiperidine provide a basis for modeling ground states for the reactions of benzyl alcohol and benzaldehyde. The active sites with coenzymes and neighboring amino acid residues are superpositioned in Fig. 7. Benzyl alcohol is shown in the same position as is observed with pentafluorobenzyl alcohol, with its oxygen at 2.0 Å to the catalytic zinc and 2.5 Å to Ser-48 OG, and its pro-R hydrogen directed toward its destination on C4N of NAD+. Benzaldehyde is positioned with its oxygen ~ 2.2 Å from the zinc and 2.7 Å to Ser-48 OG, as found for ligands in the enzyme-NADH complexes (Table 3). The carbonyl group overlaps the positions for the carbonyl groups of the formamide inhibitors (N-formylpiperidine, N-cyclohexylformamide, N-1-methylhexylformamide, N-benzylformamide), and the benzene ring overlaps the position for the piperidine ring in the complex with N-formylpiperidine [5]. The benzene ring of the modeled benzaldehyde is rotated substantially relative to that of the benzaldehyde, but both rings are within the hydrophobic barrel that accommodates many substrates. Alterative conformations of Leu-57 and Leu-116 are observed in various complexes of ADH1E and provide flexibility in the substrate specificity. The ground state for benzaldehyde is planar, with a high energy barrier (~ 5–9 kcal/mole) to rotate the carbonyl O by 90 ° out of the plane [44]. Binding to the enzyme and depolarization of the carbonyl group by the zinc can provide a favorable interaction enthalpy of ~ 5.5 kcal/mole as estimated from Raman spectroscopic studies with N-cyclohexylformamide [33] and contribute to the rotation of the carbonyl group that leads to the formation of the alcohol. In the model, C4N of the nicotinamide ring (with the pro-R hydrogen) is about 3.7 Å from the carbonyl carbon (C7) of benzaldehyde with an angle (C4 – H – C7) of ~ 160 °, and some repositioning is expected to form the transition state.

Fig. 7.

Model of the active site with benzyl alcohol (BOH) and benzaldehyde (HBX). The structure with benzyl alcohol is shown with atom coloring, carbon in gray and hydrogens in cyan, and the catalytic zinc is a ball to which the oxygen of the alcohol is bound. The structure is the same as the one determined for NAD+ and pentafluorobenzyl alcohol (4DWV.pdb) except that the fluorines have been removed. The model with benzaldehyde (green) has two hydrogens on C4N of the NADH and alternative conformations of Leu-57 and Leu-116, based on the structures with NADH and 4-methylbenzyl alcohol (7K35.pdb), N-benzylformamide (5VL0.pdb), and N-formylpiperdine (1LDE.pdb).

Several computational studies suggest that the transition state for hydrogen transfer resembles the alcohol and a puckered nicotinamide ring [45–51]. The hydrogen is transferred with quantum mechanical tunneling, which occurs directly with a donor-acceptor distance between the reacting carbons of ~2.7 Å. Thus the observed NAD+-alcohol complex appears to resemble a “tunneling ready state” that could reach the transition state with equilibrium dynamics [51]. However, it appears that the benzaldehyde must rotate to move the reacting carbon closer to the nicotinamide ring, accompanied by rotation of the oxygen out of the plane of the benzene ring and potentially by movements of the side chains of neighboring leucine residues. The structures of the abortive NADH-alcohol complexes presented in this study show that there is room to accommodate the motions. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that a large proportion of the enzyme substrate complexes can readily approach “near attack conformations” defined with a C4–H–C7 angle ≥ 132° and a distance between donor H to acceptor C ≤ 3.0 Å [49]. Further quantum chemical computations starting with relevant structural models would be useful to determine the energetics of hydrogen transfer of this enzyme.

5. Databases

Coordinates and structure factor amplitudes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 7K35, 7JQA, and 6XT2.

Fig. 4.

Structure of the A subunit of the abortive complex with NADH and 4-bromobenzyl alcohol (BRB). The electron density map is contoured at ~0.7 e−/Å3. Atoms have the usual coloring, and the bromine is brown.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The University of Iowa Crystallography Facility for use of equipment and resources, Lokesh Gakhar for assistance with the crystallography, Eric N. Brown for some data collection, Baskar Raj Savarimuthu for some initial model building, and Kristine B. Berst for preparation of enzyme for crystallization. The authors also thank Hans Eklund for mentoring and leadership on crystallography of alcohol dehydrogenases and Erling Wikman for maintaining the Molray server in the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology (ICM) at Uppsala University. This investigation used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We thank the staff for support during data collection on beamline GM/CA 23-ID at APS. GM/CA@APS has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006).

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, AA00279, and National Institute of General Medicine, GM078446.

Abbreviations:

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- MPD

2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- [1].Sund H, Theorell H, Alcohol Dehydrogenases, The Enzymes, 7 (1963) 25–83. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brändén CI, Jörnvall H, Eklund H, Furugren B, Alcohol Dehydrogenases, The Enzymes, 3rd Ed., 11 (1975) 103–190. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Al-Karadaghi S, Cedergren-Zeppezauer ES, Hovmoller S, Petratos K, Terry H, Wilson KS, Refined crystal structure of liver alcohol dehydrogenase NADH complex at 1.8-Angstrom resolution, Acta Crystallogr. D50 (1994) 793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cho H, Ramaswamy S, Plapp BV, Flexibility of liver alcohol dehydrogenase in stereoselective binding of 3-butylthiolane 1-oxides, Biochemistry, 36 (1997) 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ramaswamy S, Scholze M, Plapp BV, Binding of formamides to liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 36 (1997) 3522–3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meijers R, Morris RJ, Adolph HW, Merli A, Lamzin VS, Cedergren-Zeppezauer ES, On the enzymatic activation of NADH, J. Biol. Chem 276 (2001) 9316–9321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rubach JK, Plapp BV, Mobility of fluorobenzyl alcohols bound to liver alcohol dehydrogenases as determined by NMR and X-ray crystallographic studies, Biochemistry 41 (2002) 15770–15779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Venkataramaiah TH, Plapp BV, Formamides mimic aldehydes and inhibit liver alcohol dehydrogenases and ethanol metabolism, J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 36699–36706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meijers R, Adolph HW, Dauter Z, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS, Cedergren-Zeppezauer ES, Structural evidence for a ligand coordination switch in liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 46 (2007) 5446–5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Plapp BV, Ramaswamy S, Atomic-resolution structures of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase with NAD+ and fluoroalcohols define strained Michaelis complexes, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 4035–4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Plapp BV, Savarimuthu BR, Ferraro DJ, Rubach JK, Brown EN, Ramaswamy S, Horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase: zinc coordination and catalysis, Biochemistry 56 (2017) 3632–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Eklund H, Plapp BV, Samama JP, Brändén C-I, Binding of substrate in a ternary complex of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, J. Biol. Chem, 257 (1982) 14349–14358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ramaswamy S, Eklund H, Plapp BV, Structures of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase complexed with NAD+ and substituted benzyl alcohols, Biochemistry 33 (1994) 5230–5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].LeBrun LA, Park DH, Ramaswamy S, Plapp BV, Participation of histidine-51 in catalysis by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 43 (2004) 3014–3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Park DH, Plapp BV, Isoenzymes of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase active on ethanol and steroids. cDNA cloning, expression, and comparison of active sites, J. Biol. Chem 266 (1991) 13296–13302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pflugrath JW, The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection, Acta Crystallogr. D55 (1999) 1718–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS, Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments, Acta Crystallogr. D67 (2011) 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA, REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures, Acta Crystallogr. D67 (2011) 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rubach JK, Plapp BV, Amino acid residues in the nicotinamide binding site contribute to catalysis by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 42 (2003) 2907–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M, Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models, Acta Crystallogr. A47 (1991) 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sheldrick GM, Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallogr. C71 (2015) 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, Jain S, Lewis SM, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Adams PD, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation, Protein Sci. 27 (2018) 293–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Merritt EA, Comparing anisotropic displacement parameters in protein structures, Acta Crystallogr. D55 (1999) 1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harris M, Jones TA, Molray - a web interface between O and the POV-Ray ray tracer, Acta Crystallogr. D57 (2001) 1201–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brunger AT, Free R-value - A novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures, Nature 355 (1992) 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim K, Plapp BV, Inversion of substrate specificity of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase by substitutions of Ser-48 and Phe-93, Chem. Biol. Interact 276 (2017) 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yahashiri A, Rubach JK, Plapp BV, Effects of cavities at the nicotinamide binding site of liver alcohol dehydrogenase on structure, dynamics and catalysis, Biochemistry 53 (2014) 881–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hardman MJ, Blackwell LF, Boswell CR, Buckley PD, Substituent effects on the presteady-state kinetics of oxidation of benzyl alcohols by liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Eur. J. Biochem 50 (1974) 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dworschack RT, Plapp BV, pH, isotope, and substituent effects on the interconversion of aromatic substrates catalyzed by hydroxybutyrimidylated liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 16 (1977) 2716–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shearer GL, Kim K, Lee KM, Wang CK, Plapp BV, Alternative pathways and reactions of benzyl alcohol and benzaldehyde with horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 32 (1993) 11186–11194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sekhar VC, Plapp BV, Rate constants for a mechanism including intermediates in the interconversion of ternary complexes by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 29 (1990) 4289–4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Plapp BV, Catalysis by alcohol dehydrogenses, in: Kohen A, Limbach H-H (Ed.) Isotope Effects in Chemistry, Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 2006, pp. 811 – 835. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Deng H, Schindler JF, Berst KB, Plapp BV, Callender R, A Raman spectroscopic characterization of bonding in the complex of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase with NADH and N-cyclohexylformamide, Biochemistry 37 (1998) 14267–14278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Andersson P, Kvassman J, Lindström A, Oldén B, Pettersson G, Effect of NADH on the pKa of zinc-bound water in liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Eur. J. Biochem 113 (1981) 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shore JD, Gutfreund H, Brooks RL, Santiago D, Santiago P, Proton equilibria and kinetics in the liver alcohol dehydrogenase reaction mechanism, Biochemistry 13 (1974) 4185–4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Evans SA, Shore JD, The role of zinc-bound water in liver alcohol dehydrogenase catalysis, J. Biol. Chem 255 (1980) 1509–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kvassman J, Pettersson G, Unified mechanism for proton-transfer reactions affecting the catalytic activity of liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Eur. J. Biochem 103 (1980) 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kovaleva EG, Plapp BV, Deprotonation of the horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase-NAD+ complex controls formation of the ternary complexes, Biochemistry 44 (2005) 12797–12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kvassman J, Larsson A, Pettersson G, Substituent effects on the ionization step regulating desorption and catalytic oxidation of alcohols bound to liver alcohol dehydrogenase, Eur. J. Biochem 114 (1981) 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kim K, Plapp BV, Substitutions of amino acid residues in the substrate binding site of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase have small effects on the structures but significantly affect catalysis of hydrogen transfer, Biochemistry 59 (2020) 862–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Plapp BV, Eklund H, Brändén C-I, Crystallography of liver alcohol dehydrogenase complexed with substrates, J. Mol. Biol 122 (1978) 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bignetti E, Rossi GL, Zeppezauer E, Microspectrophotometric measurements on single crystals of coenzyme containing complexes of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase, FEBS Lett. 100 (1979) 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shanmuganatham KK, Wallace RS, Lee AT-I, Plapp BV, Contribution of buried distal amino acid residues in horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase to structure and catalysis, Protein Sci. 27 (2018) 750–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Speakman LD, Papas BN, Woodcock HL, Schaefer HF, The microwave and infrared spectroscopy of benzaldehyde: conflict between theory and experimental deductions, J. Chem. Phys 120 (2004) 4247–4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Alhambra C, Corchado JC, Sánchez ML, Gao J, Truhlar DG, Quantum dynamics of hydride transfer in enzyme catalysis, J. Am. Chem. Soc 122 (2000) 8197–8203. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Agarwal PK, Webb SP, Hammes-Schiffer S, Computational studies of the mechanism for proton and hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 122 (2000) 4803–4812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Webb SP, Agarwal PK, Hammes-Schiffer S, Combining electronic structure methods with the calculation of hydrogen vibrational wavefunctions: application to hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase, J. Phys. Chem. B 104 (2000) 8884–8894. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Villà J, Warshel A, Energetics J Phys. Chem. B 105 (2001) 7887–7907. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Luo J, Bruice TC, Dynamic structures of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase (HLADH): Results of molecular dynamics simulations of HLADH-NAD+-PhCH2OH, HLADH-NAD+-PhCH2O−, and HLADH-NADH-PhCHO, J. Am. Chem. Soc 123 (2001) 11952–11959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cui Q, Elstner M, Karplus M, A theoretical analysis of the proton and hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase (LADH). J. Phys. Chem. B 106 (2002) 2721–2740. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Roston D, Kohen A, Elusive transition state of alcohol dehydrogenase unveiled, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 107 (2010) 9572–9577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]