Abstract

Relatively little is known about the possible effects of personalized genetic risk information on smoking, the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality. We examined the acceptability and potential behavior change associated with a personalized genetically-informed risk tool (RiskProfile) among current smokers. Current smokers (n=108) were enrolled in a pre-post study with three visits. At Visit 1, participants completed a baseline assessment and genetic testing via 23andMe. Participants’ raw genetic data (CHRNA5 variants) and smoking heaviness were used to create a tailored RiskProfile tool that communicated personalized risks of smoking-related diseases and evidence-based recommendations to promote cessation. Participants received their personalized RiskProfile intervention at Visit 2, approximately 6 weeks later. Visit 3 involved a telephone-based follow-up assessment 30 days after intervention. Of enrolled participants, 83% were retained across the three visits. Immediately following intervention, acceptability of RiskProfile was high (M=4.4; SD=0.6 on scale of 1 to 5); at 30-day follow-up, 89% of participants demonstrated accurate recall of key intervention messages. In the full analysis set of this single-arm trial, cigarettes smoked per day decreased from intervention to 30-day follow-up [11.3 vs. 9.8, difference=1.5, 95% CI (0.6—2.4), p=.001]. A personalized genetically-informed risk tool was found to be highly acceptable and associated with a reduction in smoking, although the absence of a control group must be addressed in future research. This study demonstrates proof of concept for translating key basic science findings into a genetically-informed risk tool that was used to promote progress toward smoking cessation.

Keywords: genetic risk, smoking, precision medicine, behavior change, intervention

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, major scientific advances have revealed how personal factors, including genetic risk information, can be used to predict complex diseases and other important health outcomes [1–4]. However, these basic science discoveries have not yet been translated into interventions for behavioral health targets, including smoking cessation [5]. Because of its many harms, smoking may be an ideal target for novel approaches to communicate personalized risks, motivate and facilitate behavior change, and mitigate disease [6].

Prior research has attempted to return genetic susceptibility results to motivate positive behavior change, including physical activity, diet, sun protection, medication use, and smoking cessation, but this has yielded mixed findings. Whereas previous meta-analyses revealed little-to-no behavior change following the return of genetic risk estimates for long-term health outcomes [7, 8], a newer meta-analysis found moderate increases in healthy behaviors (e.g., sunscreen use, exercise, healthy eating) >6 months after return of results among individuals with high genetic risk for a range of complex diseases including melanoma and Alzheimer’s disease [9].

These studies may not reflect the potential of genetic risk feedback to alter smoking since they may not address a health risk of similar perceived likelihood or where the risk can be substantially addressed in such a relatively circumscribed behavior change: smoking cessation. Other risks may require life-long behavior change patterns in diet or exercise. Therefore, at present, relatively little is known about the possible effects of personalized genetic risk information on smoking, the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality [10]. The current research attempts to leverage established research findings on the genetics of smoking and its harms by using known multiple genetic loci associated with smoking behavior, associated disease risks, and the likelihood of cessation [11].

Multiple large genome-wide meta-analyses have identified several genetic markers for smoking initiation, smoking quantity, and smoking cessation [12–16], with the most robust signal near the α5 nicotinic cholinergic receptor gene (CHRNA5) [17, 18]. There is now evidence that variants in and near this gene have prognostic significance for risk of smoking-related diseases, likelihood of smoking cessation, and possibly response to nicotine replacement therapy [19, 20]. Individuals with high-risk genetic variants versus those without such variants are more likely on average to: (1) smoke especially heavily [12, 19], (2) have 2-fold increased risk for lung cancer [14–18], (3) develop lung cancer 4 years earlier [17, 18], (4) quit smoking 4 years later [17, 18], and (5) have lower success with unassisted quit attempts [20]. Translation of these genomic discoveries into effective communication and motivational strategies could meaningfully enhance the reach of smoking treatment by activating smokers to quit smoking and use evidence-based cessation treatments to do so [4, 5, 11, 21, 22].

In this study, we tested the potential utility of a brief smoking motivational intervention that uses CHRNA5 genetic markers to activate behavior change in smokers by conveying personalized risk information related to their smoking and its risks. There is considerable evidence that both personalization and tailoring can enhance the motivational impact of health risk information [23, 24], such as by presenting content with personal details (e.g., race, genetic information) and tailored to reflect the individual’s status, risks, and opportunities. The intervention evaluated in this study features both personalization and tailoring, offering individualized information regarding potential risks and harms based on a person’s genetic profile. Such a motivational intervention addressing smoking might motivate quit attempts and promote treatment uptake and adherence [5, 21]. We therefore examined smokers’ attitudinal and behavioral responses to RiskProfile, a novel genetically-informed risk tool designed to motivate and activate smokers for cessation treatment. In this pretest-posttest study, we engaged current smokers in genetic testing, delivered a genetically-informed risk tool, and examined the acceptability, perceived usefulness, and smoking-related behavior change as a function of exposure to RiskProfile.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and Participants

Participants included adults aged 21 or older from the Greater St. Louis, MO region who self-reported past month smoking of combustible cigarettes. Participants were recruited from existing clinical research study registries and from the broader community using multiple recruitment methods (e.g., posted flyers, online ads) to take part in a study to better understand ways to communicate how one’s genetics impact smoking.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by an institutional review board in the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St. Louis (IRB ID: 201704049). The research was conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Intervention

This study examined a personalized genetic risk tool (RiskProfile) designed to be an important component of a genetically-informed smoking cessation intervention that ultimately would provide both risk information and a treatment algorithm based on that information. We co-designed the content and format of RiskProfile in collaboration with a wide range of potential end-users, including current smokers [25]. We also utilized expertise in genetics and epidemiology to develop an algorithm that integrated genetic (i.e., CHRNA5 variants) and phenotypic (i.e., average cigarettes per day; CPD) factors to estimate individualized risk of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and difficulty quitting smoking. The genetic markers we selected were specific by ancestry; for European Americans: rs16969968, rs75106522, and rs11631955; for African Americans: rs16969968 and rs2036527; for individuals who identified as neither European American nor African American: rs16969968. The algorithm also incorporated personalized data on average cigarettes smoked per day to tailor each participant’s RiskProfile. Additional methods for generating each personalized RiskProfile can be found at https://osf.io/tmwyn/.

The personalized RiskProfile was designed and packaged into a visually appealing risk communication tool. Where possible, we utilized best practices for risk communication, including: (1) aiming to demonstrate both competence and a caring approach, (2) using simple visual aids, (3) clarifying data with verbal explanation, and (4) balancing use of positive/negative and gain/loss frames [26]. For this current smoker population, RiskProfile offered personalized risk levels for lung cancer, COPD, and difficulty quitting smoking, depicted along a visual continuum and also categorized as “at risk”, “at high risk”, or “at very high risk”. Participants received actionable information about the benefits of quitting or reducing smoking, including visualization and discussion of how behavioral changes could reduce their risk along the continuum. Finally, the tool provided all participants with treatment recommendations and referral to freely available “take-home” resources—specifically, curated information about how to access the Quitline, SmokeFreeTXT program, and QuitGuide/QuitStart smartphone apps—to support smoking cessation attempts.

Study Design

This single-arm trial involved 3 participant visits (two in-person at the medical campus and one by telephone). During Visit 1, all participants completed a baseline assessment and received genetic testing by contributing DNA via saliva sample using 23andMe genotyping kits. All saliva samples were sent to 23andMe for genetic testing and analysis in a CLIA-certified laboratory. Between Visits 1 and 2, participants received the standard 23andMe online report of genetic health and ancestry approximately 2 weeks after Visit 1; this report did not include any information about genomic smoking risks. Once genetic test results were available, we obtained participants’ 23andMe raw genetic data to personalize each RiskProfile.

Participants were then invited back for Visit 2 approximately 6 weeks after Visit 1 to complete a pre-intervention assessment of smoking and alcohol use and then receive their personalized RiskProfile intervention. We used a standardized script to provide a simple, pragmatic presentation of RiskProfile results; this verbal script can be found at https://osf.io/tmwyn/.

Finally, participants were invited to participate in a follow-up Visit 3 by telephone 30 days after Visit 2 to assess acceptability of RiskProfile and change in smoking-related behavior. Participants were compensated with personalized 23andMe genetic results for Visit 1 and with $25 per visit for Visits 2 and 3. Participants received up to 3 follow-up reminder calls or emails to maximize participant retention while minimizing unnecessary burden.

Assessments

Demographic information on age, sex, race, and education level was collected at Visit 1. All assessments below were modified from existing measures.

Attitudes toward Genetic Risk Results

A 9-item scale on attitudes toward receiving, using, and sharing genetic risk results for smoking and alcohol-related diseases (e.g., “It is a good idea to get genetic testing to find out whether you are at higher risk for developing smoking- related illnesses like lung cancer and emphysema”; 1=Strongly disagree, 5=Strongly agree) [27] was assessed at Visits 1 and 3.

Acceptability of Intervention

The 4-item Acceptability of Intervention Measure (e.g., “RiskProfile is appealing to me”; 1=Completely disagree, 5=Completely agree) [28] was assessed at Visit 2.

Decision Regret

The 5-item Decision Regret Scale regarding participants’ decision to receive their genetically-informed RiskProfile (e.g., “I would make the same choice if I had to do it over again”; 1=Strongly agree, 5=Strongly disagree) [29] was measured at Visit 3.

Comprehension and Recall of Intervention Messages

A 2-item measure assessed self-reported comprehension of RiskProfile (“How well do you understand your RiskProfile”; 1=Not at all, 5=Extremely), and objective recall by correctly identifying three key messages from RiskProfile (“Based on your RiskProfile, quitting smoking: (1) is one of the most important things you can do for your health, (2) can reduce the onset of lung cancer and lung diseases, and (3) is easier with smoking cessation medications”) [30] this was administered at Visits 2 and 3.

A third item assessed perceptions of perceived risk as communicated by RiskProfile (“Based on your RiskProfile, what is your risk for smoking-related illnesses”; 1=Low risk, 2=Medium risk, 3=High risk, 4=Unclear/Don’t Know), although this was not a true recall item as the response options did not align with the levels of risk communicated in RiskProfile (i.e., “at risk”, “at high risk”, “at very high risk”).

Perceived Intervention Utility

A 4-item measure of perceived intervention utility (e.g., “Help me feel more in control of my health”; 1=Not at all useful, 7=Extremely useful) [31] was administered at Visits 2 and 3.

Expectations of Behavior Change

A 7-item measure of behavior change expectations (e.g., “Do you think your RiskProfile will help you use a prescription medication [like bupropion or varenicline] to help you quit?”; 0=No, 1=Yes) [32] was measured at Visits 2 and 3.

Smoking and Other Health-related Behavior Changes

Changes in current smoking behaviors were assessed in two ways. First, a 2-item measure of current smoking (frequency: “About how many days out of the last 30 days did you smoke at least one cigarette?”; heaviness: “On the days you smoked in the past month, about how many cigarettes did you usually smoke per day?”) was assessed at the beginning of all 3 visits [25]. When multiplied together, these two numbers yielded approximate cigarettes smoked in past month; this number was then divided by 30 to yield approximate cigarettes smoked per day.

Second, a 10-item measure of self-reported smoking-related behavior changes as a result of the tool (e.g., “Since you received your RiskProfile, did you cut down on how many cigarettes you smoke?”; 0=No, 1=Yes) [32] was assessed at Visits 2 and 3.

Changes in alcohol use were assessed using a 3-item measure of alcohol use (frequency, heaviness, and binge drinking in past 30 days) across all 3 visits.

Statistical Analysis

Data on all variables were first analyzed descriptively through frequencies and means. Repeated-measures ANOVA were used to test changes over time in average CPD and drinks per week. Our primary analysis involved the full analysis set; to handle missing data due to attrition, we made the conservative assumption that participants lost to follow-up were still smoking and had not changed their average CPD from the previous visit [33]. Supplementary Data File 1 includes two alternative analytic approaches: results for the completer analyses (i.e., only participants who completed all visits) and expectation-maximization algorithm (i.e., imputation to determine maximum likelihood estimates). For this proof of concept study, power analyses indicated that a sample size of 100 participants would yield adequate power to detect an effect size of f=0.16, which is a small-to-medium effect.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

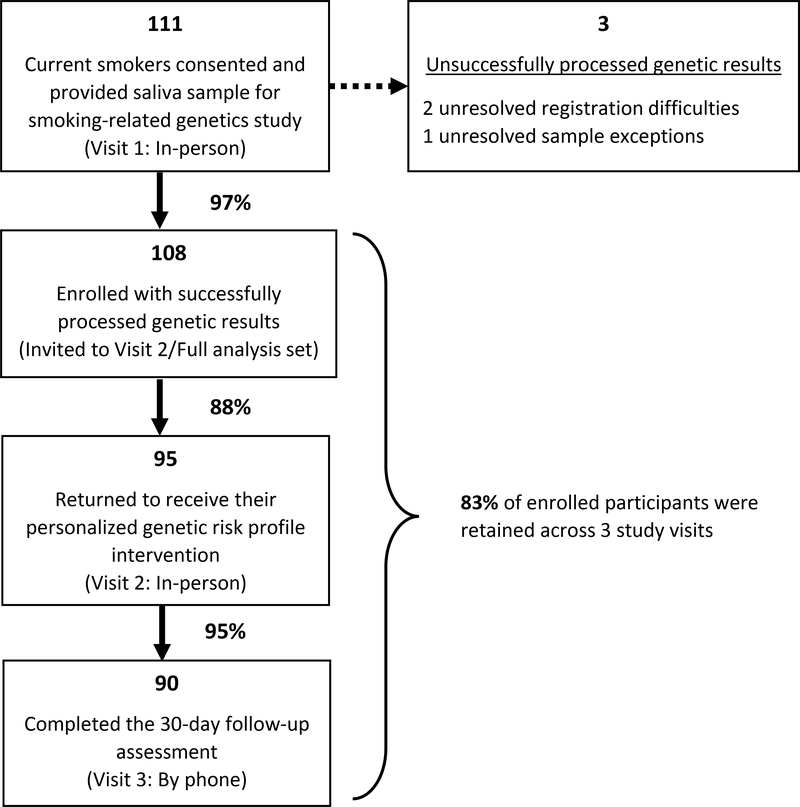

Of all consented participants who provided a saliva sample (n=111) at Visit 1, genetic test results for 108 participants (97%) were successfully processed and made available to the research team; these participants constituted the enrolled sample (i.e., full analysis set) and were invited to receive the intervention at Visit 2 (Figure 1). Of these 108 current smokers, 95 (88%) returned to receive their personalized RiskProfile at Visit 2. Finally, 90 of the 95 who received the RiskProfile (95%) completed the 30-day follow-up assessment at Visit 3. Altogether, 83% of enrolled participants were retained across the three study visits.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participation.

Importantly, participants were broadly diverse across a range of demographic categories. Nearly half of participants self-classified as people from underrepresented racial groups, and more than one-third had a high school diploma or less. The sample of current smokers reported moderate levels of smoking (12.8 CPD) and drinking (5.7 drinks per week) at baseline (Table 1). Of the 108 enrolled participants, 16% were categorized as “at risk”, 34% as “at high risk”, and 50% as “at very high risk”.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled participants.

| Participants (n=108) | |

|---|---|

| Average age (SD) | 47.5 (12.7) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 59% |

| Male | 41% |

| Race | |

| Caucasian/White | 58% |

| African American/Black | 34% |

| Other | 7% |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or less | 35% |

| Some college or technical school | 36% |

| 4-year college degree | 22% |

| Graduate degree | 6% |

| Average cigarettes per day (baseline) | 12.8 |

| Average drinks per week (baseline) | 5.7 |

Acceptability and Usability of RiskProfile

Attitudes toward Genetic Risk Results

Attitudes toward receiving and using genetic risk results were favorable at pre-intervention (M=4.3; SD=0.6; scale=1 to 5) and remained so at post-intervention (M=4.3; SD=0.5). In addition, 60% of participants reported sharing results from their RiskProfile, most commonly with a spouse/partner (56% of those who shared) or a friend (28% of those who shared).

Acceptability of Intervention

Participants reported high levels of acceptability (M=4.4; SD=0.6; scale=1 to 5), indicating intervention appeal and participant approval of the tool in its present form. Approximately 83% of participants rated the intervention ≥4.0, suggesting overall acceptability of RiskProfile.

Decision Regret

Participants reported exceedingly low levels of regret regarding their decision to receive their RiskProfile (M=1.4; SD=0.4; scale=1 to 5). Of note, 99% of participants affirmed that they would make the same decision again. No participants reported decision regret scores greater than M=2.4, confirming little or no decision regret nor harms associated with receiving RiskProfile.

Comprehension and Recall of Results

Approximately 97% of participants immediately following intervention receipt and 90% of participants 30 days after intervention reported understanding RiskProfile moderately to extremely well (rated 3–5 on scale of 1 to 5). In addition, 81% and 89% of participants at these time points, respectively, demonstrated accurate recall of key messages by correctly endorsing that RiskProfile stated all of the following: that quitting smoking (1) is one of the most important things you can do for your health, (2) can reduce the onset of lung cancer and lung diseases, and (3) is easier with smoking cessation medications.

Although not an appropriate recall item due to ambiguity in interpreting the response options, it is noteworthy that 69% of participants interpreted their personalized risk for smoking-related illnesses to be “High”, although this was confounded by the actual risk category (by different names) in which they were placed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of smoking-related risk based on risk level communicated (n=95).

| Perceived risk of smoking-related illnesses* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk | Medium Risk | Low Risk | Overall | ||

| Risk level communicated in RiskProfile | At Very High Risk | 83% | 11% | 2% | 49% |

| At High Risk | 70% | 21% | 9% | 35% | |

| At Risk | 27% | 27% | 47% | 16% | |

| Overall | 69% | 17% | 12% | ||

n=2 participants indicated “Unclear/Don’t Know” level of risk, not included in table.

Potential Utility of RiskProfile

Perceived Intervention Utility

Participants reported high levels of potential utility of RiskProfile immediately following intervention receipt (M=5.8; SD=0.8; scale=1 to 7) and 30 days after intervention (M=5.4; SD=1.0). At these respective time points, 91% and 78% of current smokers found the tool useful-to-extremely useful overall and for defined purposes, including helping to better understand their health (96% and 86%), helping to cope with health risks (84% and 73%), and feeling more in control of their health (81% and 63%).

Expectations of Behavior Change

Immediately following intervention receipt, participants endorsed expectations that RiskProfile would help them make a variety of behavior changes, including quit smoking (73%), use a prescription medication like bupropion or varenicline (61%), use an over-the-counter aid like the nicotine patch or gum (53%), and switch to e-cigarettes (19%). Even among those who did not expect to quit smoking, 58% expected to make a quit attempt, and 46% expected that they would reduce cigarette smoking.

Smoking-related Behavior Change

Supplementary Data File 1 provides results for the completer analyses (n=90) and expectation-maximization algorithm (n=108). The smoking-related behavior change results presented below reflect the more conservative full analysis set (n=108), which assumed that the 18 participants with incomplete data did not make any positive smoking-related behavior changes.

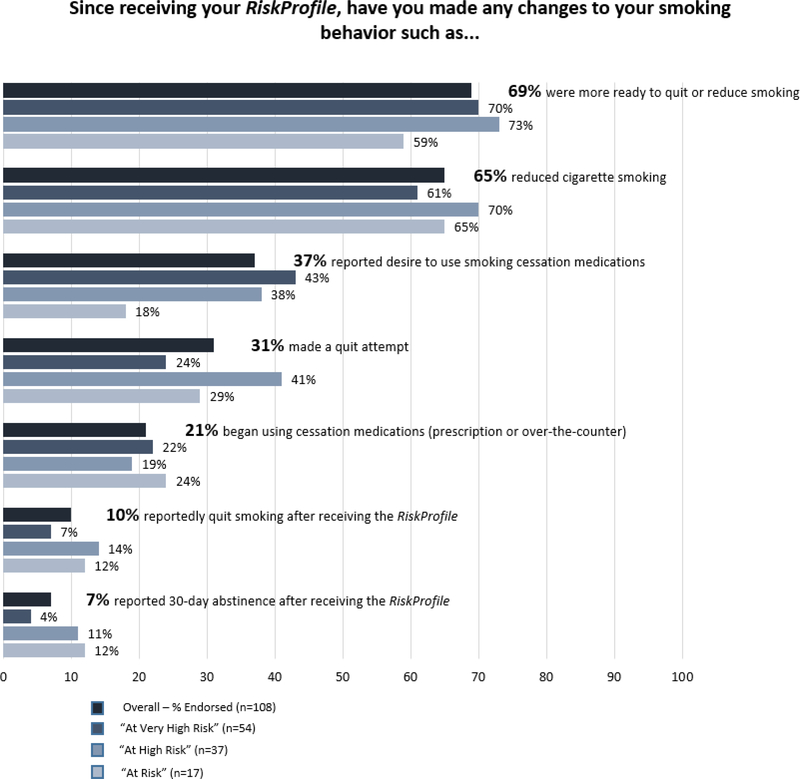

Preparing to Quit

Figure 2 depicts key findings regarding smoking-related behavior change, stratified by risk level, as a function of exposure to RiskProfile. In the full analysis set at the 30-day post-intervention visit, 69% of participants reported increased readiness to quit or reduce smoking, and 31% reported making a quit attempt as a function of receiving RiskProfile. Approximately 37% of current smokers reported desire to use smoking cessation medications, and about one-fifth (21%) reportedly began using cessation pharmacotherapy (i.e., prescription medications or over-the-counter aids such as nicotine patch or gum) following receipt of RiskProfile. Of note, 77% reported at least one behavior change related to their smoking (e.g., made a quit attempt, tried FDA-approved cessation medication).

Figure 2.

RiskProfile led to smoking-related behavior change (n=108).

Quitting Smoking

Among the full analysis set, 11 (10%) reported that RiskProfile enabled them to quit smoking. Of note, only 8 of these 11 (7% overall) reported having smoked 0 cigarettes for the full 30 days between Visits 2 and 3. Some participants may have quit smoking amid the 30-day period, which may reconcile the cases of self-reported smoking cessation without 30-day abstinence. Importantly, only 2 of the 8 reporting 30-day abstinence at Visit 3 also reported 30-day abstinence at Visit 2; therefore, the remaining 6 achieved 30-day reported abstinence after receiving the intervention.

Reducing Smoking

Among the full analysis set, 65% endorsed the item indicating that they had reduced their smoking following receipt of RiskProfile.

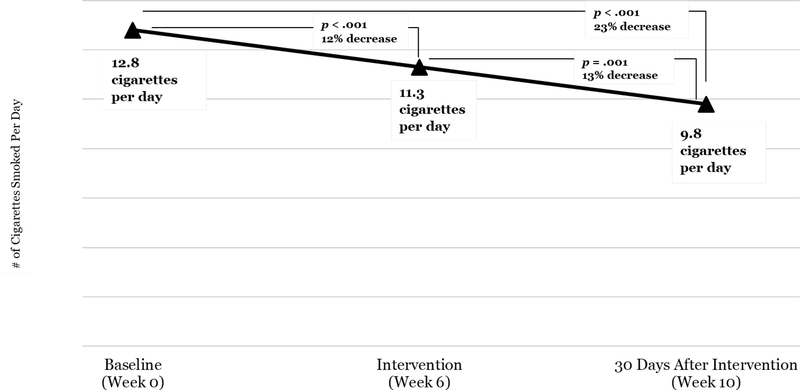

In descriptive analyses of CPD by visit, participants smoked an average of 12.8 (range=0.03–40.00; SE=0.86) vs. 11.3 (range=0.00–40.00; SE=0.81), vs. 9.8 (range=0.00–40.00; SE=0.76) CPD in Visits 1, 2, and 3, respectively (see Figure 3). This downward trend remained even when removing the 8 smokers who reported 30-day abstinence at Visit 3; among these 100 participants, the average cigarettes smoked per day was 13.1 vs 11.7 vs. 10.6 in Visits 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Figure 3.

Reduced smoking after receiving RiskProfile (n=108).

Further, we examined the proportion of participants who reported reductions in CPD from Visit 2 to Visit 3, as compared to reductions in CPD from Visit 1 to Visit 2. Specifically, from Visit 2 to Visit 3, 48 (44%) decreased their cigarette use, 46 (43%) did not change, and 14 (13%) increased their cigarette use, whereas from Visit 1 to Visit 2, 44 (41%) decreased their cigarette use, 43 (40%) did not change, and 21 (19%) increased their cigarette use.

A repeated measures ANOVA indicated that mean CPD differed between time points (F(2, 214)=19.995, p<0.001). Post hoc tests revealed that mean CPD decreased from Visit 2 to Visit 3 [difference=1.5, 95% CI (0.6—2.4), p=.001], indicating a reduction in cigarette smoking from pre- to post-intervention. Post hoc tests also found decreases in cigarettes smoked from Visit 1 to Visit 2 [difference=1.5, 95% CI (0.8—2.3), p<.001] and from Visit 1 to Visit 3 [difference=3.0, 95% CI (1.8—4.1), p<.001]. Of note, although the absolute reduction in cigarettes was the same between T1-T2 and T2-T3, the relative reduction was slightly greater from T2-T3 (13.3%) compared to T1-T2 (11.7%).

In assessing smoking reduction by risk level, it is important to note that one criterion for risk level designation was CPD. Therefore, detecting an absolute reduction (but not necessarily a relative reduction) in CPD was most likely in the highest risk group. Indeed, a risk level by time interaction analysis revealed that the reduction in CPD from Visit 1 to Visit 3 varied by risk level (F(4, 210)=3.559, p=0.008), and the absolute reduction in CPD appeared to be greatest among participants categorized as “at very high risk” (18.0 vs. 16.2 vs. 13.7; difference=4.3), compared to those “at high risk” (9.4 vs. 7.4 vs. 6.9; difference=2.5) and “at risk” (3.7 vs. 4.1 vs. 4.0; difference=−0.3). Of note, however, the relative reduction in the “at very high risk” (highest risk) group (24%) was not greater than the relative reduction in the “at high risk” (second highest risk) group (27%). Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates change in CPD across visits, stratified by 1) RiskProfile status, 2) smoking heaviness, and 3) level of genetic risk.

Importantly, the reduction in CPD from Visit 2 to Visit 3 also varied by risk level (F(2, 105)=3.101, p=0.049), and both absolute and relative reduction in CPD from Visit 2 to Visit 3 appeared to be greatest among participants categorized as “at very high risk” (difference=2.5; 16% reduction), compared to those “at high risk” (difference=0.5; 7% reduction) and “at risk” (difference=0.1; 3% reduction). However, examining the proportions of participants with reductions in CPD from Visit 2 to Visit 3 did not reveal clear differences by risk level among participants “at very high risk” (46%), “at high risk” (41%), and “at risk” (47%).

Of note, 72 of 95 (76%) participants from Visit 2 indicated that they had viewed their standard 23andMe online report of genetic health and ancestry that was sent to them via email between Visits 1 and 2. Participant viewing of 23andMe results was not associated with change in mean cigarettes smoked per day from Visit 2 to Visit 3 (p=.694).

An open-ended question about other smoking-related behavior changes revealed several comments about (1) limiting exposure to smoking cues (e.g., “avoiding second-hand smoke”, “more aware of what triggers desire to smoke”), (2) restricting cigarette use (e.g., “stopped smoking in car”, “not smoking first thing in morning”, (3) replacing with competing alternatives (e.g., “replaced the habit”, “found hobbies that wouldn’t allow me to smoke”, and (4) incorporating mindful awareness into quit attempts (e.g., “being more mindful about smoking”, “more aware of each cigarette and what it’s doing to me”).

Other Health-related Behavior Changes

Alcohol Use

To assess discriminant validity of the intervention—that it does not change, or changes to a lesser extent, behaviors that it theoretically should not change—we examined whether RiskProfile was associated with changes to a comparable high-risk health behavior (i.e., alcohol use) that was not addressed in RiskProfile. Participants in the completed sample consumed an average of 5.9 drinks per week at baseline (Visit 1), 6.4 drinks per week immediately prior to the intervention (Visit 2), and 5.1 drinks per week 30 days after the intervention (Visit 3). A repeated measures ANOVA determined that mean drinks per week did not differ between time points (F(2, 178)=0.809, p=0.447).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we engaged current smokers in a motivational intervention conveying health risk from individuals’ genetic data. The study included populations that suffer disparate harm from tobacco and who are less likely to be advised to quit or have access to treatment, including communities of color and those of low socioeconomic status [34]. Moreover, the data suggest that the motivational intervention was well accepted, the communicated information was understood, and that it activated participants to try to quit or reduce their smoking.

Over a span of 3 months, we consented over 100 current smokers with varying interest in quitting smoking. We generated a personalized RiskProfile intervention for the 97% of participants with successfully processed genetic test results, and 83% of enrolled participants were retained across the three study visits. This level of recruitment and retention suggests the feasibility of conducting similar genetics-based intervention research in the future. In addition, attitudes toward receiving, using, and sharing smoking-related genetic results were consistently high across the duration of the study. This accords with other evidence that the public has favorable attitudes toward obtaining and acting on personalized genetic health information [25, 35–39].

Participants found the personalized genetic risk tool to be acceptable, comprehensible, and potentially useful for a variety of purposes including understanding and coping with health risks, informing steps to mitigate risks, and motivating smoking-related behavior changes. RiskProfile therefore demonstrated potential utility and proof of concept as a strategy to enhance interest in and potentially improve the reach of smoking cessation treatment.

In addition, as concerns may persist about the potential for genetic fatalism [9], it is important to highlight that (1) the benefits observed in this study followed an intervention in which all participants were given the message that they were at relatively high risk for smoking-related diseases, and (2) the benefits appeared to be greatest when the communicated risk information was at the highest level (i.e., “at very high risk”). Furthermore, participants did not report significant regrets associated with receiving RiskProfile, which aligns with a lack of adverse psychological reactions to receiving genetic risk information as observed in prior research [8, 9, 35–37]. This study thus adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting little risk of negative behavioral or psychological effects from the return of genetic results (e.g., fatalism, risk compensation, and adverse effects leading to decision regret).

Finally, among the full analysis set (n=108), we observed that current smokers reported reductions in their cigarette smoking following the receipt of a personalized genetically-informed risk tool (RiskProfile). In this single-arm trial, CPD decreased by 13% (11.3 vs 9.8 CPD) from immediately before the intervention to 30-days post-intervention, with a plurality (44%) of participants reporting a reduction in CPD smoked during this time period.

Limitations

Although these findings demonstrate the promise of RiskProfile, this study has limitations. First, the study lacked a control group, which precludes strong inferences about the effects of the intervention. Thus, it is unknown the extent to which a control group would have reported similar attitudes and behaviors before and after a control intervention. Self-reported outcomes may have been influenced by perceived demand characteristics, social desirability, or acquiescence. It is also possible that the general experimental context heightened participants’ awareness of smoking risks and the need to take action and that the changes observed over time reflected this nonspecific influence rather than the RiskProfile per se. Second, participants may have self-selected into this study due to a prior interest in receiving genetic risk information; in turn, this sampling bias may have inflated the acceptability and comprehension findings. This study also relied upon retrospective verbal reports of behavior change. Perhaps ecological momentary assessment of smoking behavior would have provided greater accuracy of smoking rates over time [40].

Further, the need to minimize participant burden of assessments in this proof of concept study precluded the assessment of intermediate outcomes such as readiness to quit, desire to use pharmacotherapy, and quit attempts prior to the intervention; unfortunately, this limits the interpretability of findings about possible effects of the intervention on these variables. It is also difficult to interpret the recall data given the mismatch between categories of risk as communicated to participants and the way in which recall of risk was assessed. The sample size is small, but given that nearly half of participants (8 of 17; 47%) in the “at risk” group perceived a “low” level of risk following the intervention, it is reasonable to speculate that the intervention likely did not increase perceived risk in this group. It is plausible, however, that increasing perceived risk is only one of the possible mechanisms by which this type of tool could influence behavior change. Interestingly, Figure 2 suggests that participants in the “at risk” group were not far less likely—and in several cases, equally or more likely—to report smoking-related behavior changes than those in the “at high risk” and “at very high risk” groups. As lighter, less dependent smokers, these “at risk” individuals may have been more able to make behavioral changes with regard to smoking, even in the potential absence of increased perceived risk. Finally, the current study also lacked a longer-term follow-up (e.g., 6 months), which was beyond the current scope of establishing proof of concept; nevertheless, this would have yielded stronger evidence of efficacy.

Future Directions

Although our sample included current smokers recruited from the broader community, additional studies could extend beyond more traditional research settings to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of genetically-informed smoking interventions, as delivered routinely by healthcare professionals within real-world clinical and community health organizations. Additionally, expanding the delivery of RiskProfile through use of technology (e.g., web, mobile, QR codes) would enhance the reach of this intervention. Research could also examine mechanisms of change by which RiskProfile operates, including how it affects smokers who do not receive particularly high risk feedback (e.g., why do these smokers appear to benefit from the intervention?). Understanding the mechanisms by which RiskProfile affects smokers may provide insight into how to enhance its effectiveness (e.g., via different framing of the feedback). Perhaps the greatest need, however, is to conduct well-controlled randomized trials using more objective measures of assessment, including biochemical verification of smoking, that permit stronger inferences regarding RiskProfile effects.

Conclusion

In this study, we conducted genetic testing among current smokers, created and delivered personalized genetic risk profiles to these participants, and assessed the acceptability of the tool and its potential for promoting smoking cessation and reduction. While this study does not permit strong causal inference because it lacks a control condition, the results suggest that RiskProfile was acceptable to participants, delivered feedback on genetic risk that participants could understand, and activated participants to try to quit or reduce their smoking. Thus, this study demonstrated proof of concept for translating key basic science findings into a genetically-informed risk tool that can be used to promote progress toward smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Dr. Erika Waters of the Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine for her feedback on this paper. We also thank the study participants for providing and sharing their genetic data with the study team to inform the personalized intervention.

Financial Support: A.T. Ramsey was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant K12DA041449 and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P50CA244431. J.L. Bourdon was supported by NIDA grant T32DA015035. L-S. Chen was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA091842–16S2 and NIDA grant R01DA038076. L.J. Bierut was supported by NIDA grant R01DA036583, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345, and NCI grant P30CA091842.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: L.J. Bierut is listed as an inventor on Issued U.S. Patent 8,080,371 “Markers for Addiction” covering the use of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction, and served as a consultant for the pharmaceutical company Pfizer Inc. (New York City, New York, USA) in 2008. The remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson SJ, Rehm HL. Building the foundation for genomics in precision medicine. Nature. 2015;526:336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerman CE, Schnoll RA, Munafò MR. Genetics and smoking cessation: improving outcomes in smokers at risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007;33:S398–S405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley WT, Nilsen WJ, Manolio TA, Masys DR, Lauer M. News from the NIH: potential contributions of the behavioral and social sciences to the precision medicine initiative. Transl. Behav. Med. 2015;5:243–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LS, Horton A, Bierut L. Pathways to precision medicine in smoking cessation treatments. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;669:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein WMP, McBride CM, Allen CG, et al. Optimal integration of behavioral medicine into clinical genetics and genomics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:193–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet. 2014;384:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marteau TM, French DP, Griffin SJ, et al. Effects of communicating DNA-based disease risk estimates on risk-reducing behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007275.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollands GJ, French DP, Griffin SJ, et al. The impact of communicating genetic risks of disease on risk-reducing health behaviour: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;352:i1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frieser MJ, Wilson S, Vrieze S. Behavioral impact of return of genetic test results for complex disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2018;37:1134–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey AT, Chen LS, Hartz SM, et al. Toward the implementation of genomic applications for smoking cessation and smoking-related diseases. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018;8:7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bierut LJ. 2018 Langley Award for Basic Research on Nicotine and Tobacco: bringing precision medicine to smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22;147–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bierut LJ, Madden PA, Breslau N, et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furberg H, Kim Y, Dackor J, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature. 2008;452:638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:616–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saccone NL, Culverhouse RC, Schwantes-An TH, et al. Multiple independent loci at chromosome 15q25.1 affect smoking quantity: a meta-analysis and comparison with lung cancer and COPD. PLOS Genet 2010;6:e1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen LS, Hung RJ, Baker T, et al. CHRNA5 risk variant predicts delayed smoking cessation and earlier lung cancer diagnosis—a meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LS, Baker T, Hung RJ, et al. Genetic risk can be decreased: quitting smoking decreases and delays lung cancer for smokers with high and low CHRNA5 risk genotypes - a meta-analysis. EBioMedicine 2016;11:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, et al. α−5/α−3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol. Psychiatry 2008;13:368–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LS, Baker TB, Jorenby D, et al. Genetic variation (CHRNA5), medication (combination nicotine replacement therapy vs. varenicline), and smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bloss CS, Madlensky L, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Genomic information as a behavioral health intervention: can it work? Pers. Med. 2011;8:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waters EA, Ball L, Carter K, Gehlert S. Smokers’ beliefs about the tobacco control potential of ‘a gene for smoking’: a focus group study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor GM, Dalili MN, Semwal M, et al. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strecher VJ, McClure JB, Alexander GL, et al. Web-based smoking-cessation programs: results of a randomized trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;34:373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsey AT, Bray M, Laker PA, et al. Participatory design of a personalized genetic risk tool to promote behavioral health. Cancer Prev. Res. 2020;doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gigerenzer G & Edwards A. Simple tools for understanding risks: from innumeracy to insight. BMJ 2003;327:741–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlando LA, Sperber NR, Voils C, et al. Developing a common framework for evaluating the implementation of genomic medicine interventions in clinical care: the IGNITE Network’s Common Measures Working Group. Genet. Med. 2018;20:655–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement. Sci. 2017;12:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a Decision Regret Scale. Med. Decis. Making 2003;23:281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amendola LM, Berg JS, Horowitz CR, et al. The clinical sequencing evidence-generating research consortium: integrating genomic sequencing in diverse and medically underserved populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohler JN, Turbitt E, Lewis KL, et al. Defining personal utility in genomics: A Delphi study. Clin. Genet. 2017;92:290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Green RC. Genetic risk assessment for adult children of people with Alzheimer’s Disease: The Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s Disease (REVEAL) Study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evins AE, Culhane MA, Alpert JE, et al. A controlled trial of bupropion added to nicotine patch and behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in adults with unipolar depressive disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levinson AH. Where the U.S. tobacco epidemic still rages: Most remaining smokers have lower socioeconomic status. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartz SM, Olfson E, Culverhouse R, et al. Return of individual genetic results in a high-risk sample: enthusiasm and positive behavioral change. Genet. Med. 2015;17:374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olfson E, Hartz S, Carere DA, et al. Implications of personal genomic testing for health behaviors: the case of smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipkus IM, Schwartz-Bloom R, Kelley MJ, Pan WA. Preliminary exploration of college smokers’ reactions to nicotine dependence genetic susceptibility feedback. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015;17:337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu A, Hartz S, Smock N, et al. Most current smokers desire genetic susceptibility testing and genetically-efficacious medication. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018;13:430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senft N, Sanderson M, Selove R, et al. Attitudes towards precision treatment of smoking in the Southern Community Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2019;doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiffman S Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol. Assess. 2009;21:486–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.