Abstract

Escherichia coli is considered to be the best-known microorganism given the large number of published studies detailing its genes, genome, and biochemical functions of its molecular components. This vast literature has been systematically assembled into a reconstruction of the biochemical reaction networks that underlie E. coli’s functions; a process which is now being applied to an increasing number of microorganisms. Genome-scale reconstructed networks represent organized and systematized knowledge-bases that have multiple uses, including conversion into computational models that interpret and predict phenotypic states and the consequences of environmental and genetic perturbations. These genome-scale models (GEMs) now enable us to develop pan-genome analyses that provide mechanistic insights, detail the selection pressures on proteome allocation, and address stress phenotypes. In this Review, we first discuss the overall development of GEMs and their applications. Next, we review the evolution of the most complete GEM that has been developed to date: the E. coli GEM. Finally, we explore three emerging areas in genome-scale modeling of microbial phenotypes: collections of strain-specific models, metabolic and macromolecular expression models, and simulation of stress responses.

Table of contents blurb

Genome-scale models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of reconstructed networks that facilitate computation and prediction of phenotypes, and are useful tools for predicting the biological capabilities of microorganisms. In this Review, Fang, Lloyd and Palsson discuss the development and the emerging application of GEMs.

Introduction

Genome-scale network reconstructions are built from curated and systematized knowledge1,2 that enables them to quantitatively describe genotype–phenotype relationships. Genome-scale models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of reconstructed networks that facilitate computation and prediction of multi-scale phenotypes through the optimization of an objective function of interest3,4.

The development of a GEM requires curated metabolic knowledge bases, such as kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG)5, and an annotated genome sequence of the organism of interest. By mapping the annotated genome sequence (Fig. 1a) to the knowledge base, one can reconstruct a metabolic network composed of all known metabolic reactions (Fig. 1b). This metabolic network can be converted into a mathematical format — a stoichiometric matrix (S matrix) — where the columns represent reactions, rows represent metabolites, and each entry is the corresponding coefficient of a particular metabolite in a reaction (Fig. 1c). A cellular objective is needed to enable computation of a feasible metabolic flux that optimizes the model objective. A widely used objective function is to optimize for growth rate, represented by a biomass function6, composed of essential metabolites needed for growth. The detailed steps to reconstruct a GEM have been described in a formal protocol1.

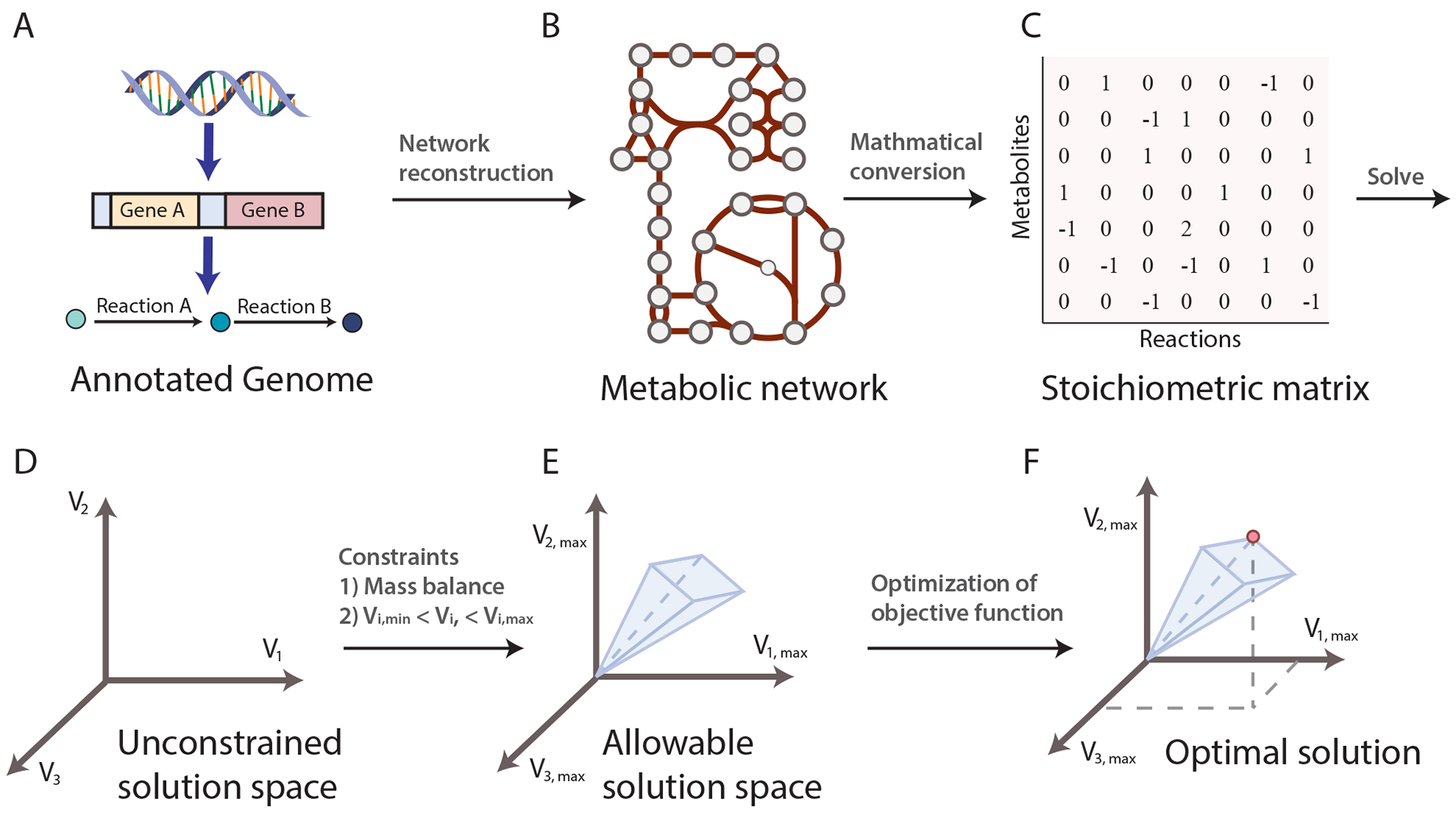

Figure 1:

Basic principles of constraint-based modeling of cellular functions. a| Metabolic genes from annotated genomes of interest and metabolic knowledge lead to metabolic reactions. b| Integration of all the metabolic reactions through shared metabolites results in the construction of a metabolic network for the organism of interest. c| The metabolic network can be converted into a stoichiometric matrix (S matrix) where rows represent metabolites, columns represent reactions, and each entry represents the reaction coefficient of a particular metabolite in a reaction. d| With the S matrix and the objective function of the model, one can solve for the flux distributions. The solution space is where all possible solutions of flux distribution reside, and each axis represents the metabolic flux of a reaction. e| Applying additional constraints will shrink the allowable solution space. Commonly used constraints include the steady state assumption and feasible ranges of metabolic flux. f| One or multiple optimal solutions can be found in the allowable solution space that optimizes the objective function of the model (as represented by the red dot in the figure).

Flux balance analysis (FBA) is the most widely used7 approach to characterize GEMs. GEMs can simulate metabolic flux states of the reconstructed network while incorporating multiple constraints to ensure the solution identified by FBA is physiologically relevant and compliant with governing constraints; such as the metabolic network topology represented by the S matrix, a steady-state assumption (for example, the internal metabolites must be produced and consumed in a flux-balanced manner), and other limits on nutrient uptake rates, enzyme capacities, and protein/gene expression profiles. The S matrix and the objective function define a system of linear equations that can be solved given the imposed constraints, resulting in a solution space (that is, a space where all feasible phenotypic states exist. (Fig. 1d, Fig. 1e). FBA can identify a single or multiple optimal flux distributions that optimize the objective function in the solution space (Fig. 1f). FBA and many other GEM analysis methods are available through COBRApy8 in python or the COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB9.

GEMs have been successfully implemented for a wide range of applications10–17, including understanding microorganisms16–22, metabolic engineering23–28, drug development29, prediction of enzyme functions30, understanding microbial community interactions31–40 and human disease41,42. One metabolic engineering application focuses on suggesting gene deletion strategies to enable overproduction of a metabolite of interest24. An algorithm called OptKnock utilizes GEMs to identify gene deletion combinations that ensure the metabolite of interest becomes an obligatory metabolic byproduct of growth (known as growth-coupled production). This framework was applied to succinate, lactate, and 1,3-propanediol production in Escherichia coli24. OptKnock combined with the E. coli GEM proposed similar gene knockout strategies as those mutant strains published in the literature, highlighting its potential in strain design24. GEMs have also been developed to study cancer metabolism. One study29 used the GEM of cancer metabolism to predict potential drug targets by simulating gene knockdowns, evaluating the damage on ATP production, and assigning cytostatic scores for genes. The model predicted 52 cytostatic drug targets, of which 40% are already targeted by known cancer treatments, leaving the rest as potential new drug targets.

Since the development of the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae43, the field has advanced substantially with a rapid rise in the number of GEMs built14,44. The number of tools and methods involved in network reconstruction and analysis has also bloomed, which accelerated the model-building process45 and enabled numerous uses of GEMs4. As of 2019, GEMs have been generated for more than 6,000 sequenced genomes either manually or through automatic GEM reconstruction tools45, covering bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes.

In addition to the well-developed uses of GEMs, recent explorations of new applications have emerged. In this Review, we describe the ongoing efforts in reconstruction to increase the coverage of the tree of life by GEMs, the expansion in the scope and applications of GEMs as illustrated by the example of E. coli, and elaborate on three emerging areas where great potential exists: multi-strain analysis using strain-specific GEMs; the incorporation of macromolecular expression pathways into existing models of metabolism to form metabolic and macromolecular expression (ME) models; and prediction of complex phenotypes, such as stress responses. We foresee the continual development and implementation of GEMs for many more organisms of interest, and them becoming an essential tool for synthetic genome engineering.

Growth of genome-scale reconstructions

Extensive effort has focused on reconstructing metabolic networks for a broad range of organisms. GEM development was initiated for bacteria and has gradually extended to archaea46–48 and eukaryotes49, including yeast50, plants51–53, and human54–56.

Exponentially growing numbers of genome sequences (Fig. 2a) enable the construction of a knowledge base of reactions and metabolites57, and the generation of increasing strain-specific network reconstructions. As the manual reconstruction of genome-scale networks is laborious and time-consuming, many automated network reconstruction tools have been developed to accelerate the reconstruction process, including ModelSeed58, CarveMe59, RAVEN60,61, and kbase62. According to a summary generated in 2019, around 5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryote metabolic network reconstructions have been reported14. Many of them can be found in GEM databases including BiGG Models63, BioModels64, MetaNetX65, MEMOSys66 and Virtual Metabolic Human67. However, the majority of these reconstructions lacked manual refinement which may result in an inaccurate description of the organism and unreliable predictions of the model14. Therefore, the community developed reconstruction and GEM quality standards MEMOTE68 to provide an overall evaluation of the quality of a reconstruction and limitations on its use.

Figure 2:

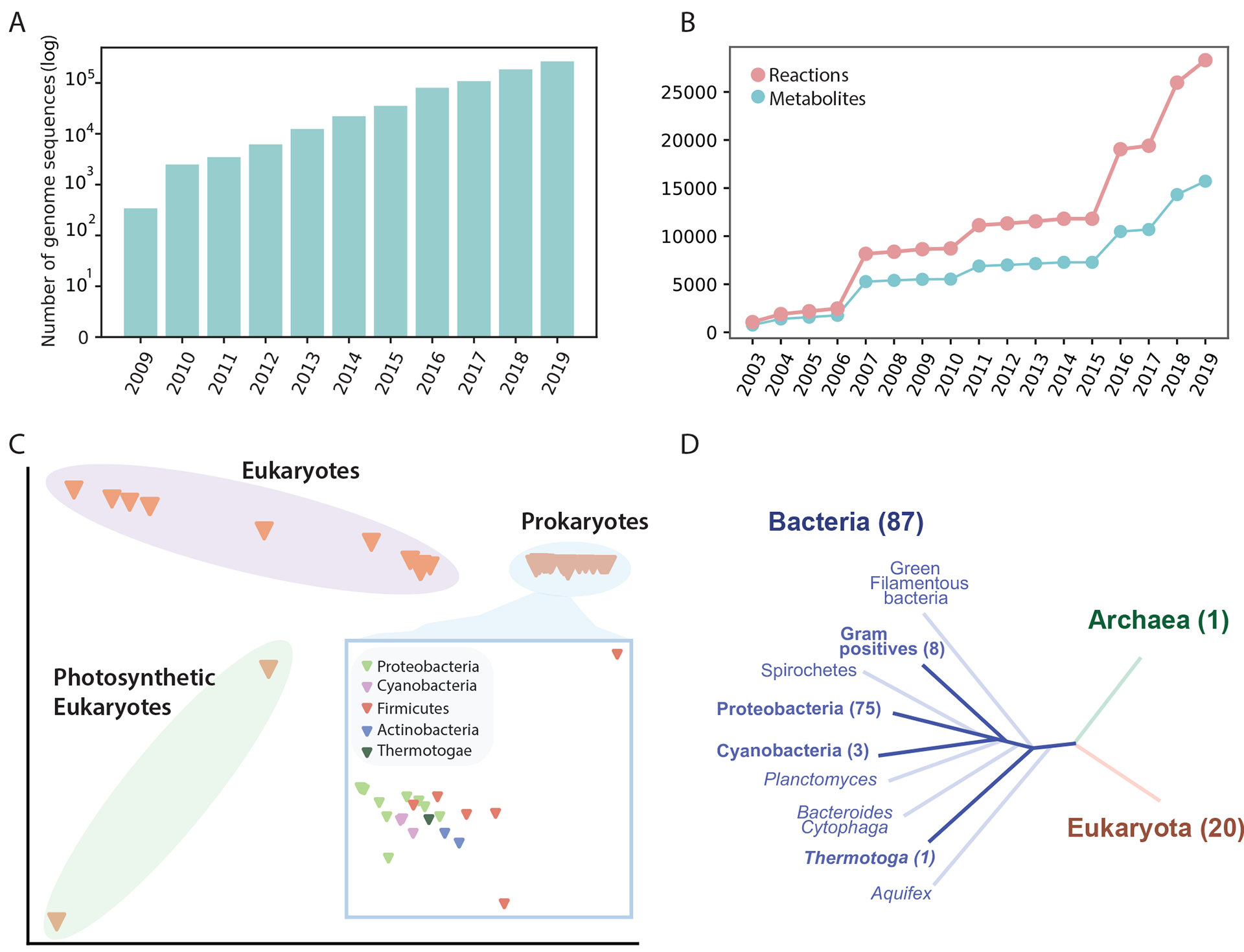

The increasing number of genome sequences and the development of genome-scale models. a| The number of public genome sequences in the PATRIC database132. b| Number of reactions and metabolites represented in 108 manually curated models in the BiGG Models database63. c| Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) of the reactomes of the 108 reconstructions. d| Coverage of the 108 reconstructions in the tree of life. The number in parenthesis represents the number of reconstructions in each branch.

Of the published reconstruction models, we focus on 108 models deposited in BiGG Models63, a widely-used repository for high-quality GEMs, where all models have been benchmarked against MEMOTE68. The content of these curated GEMs is detailed in Fig. 2. As with the availability of genome sequences, the reactions and metabolites accounted for in curated models continues to grow (Fig. 2b). Particularly, we observe a rapid increase in both reactions and metabolites since 2015, due to the development of models for eukaryotes and cyanobacteria, and species belonging to the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria phyla.

Despite the substantial growth in the number of network reconstructions, their coverage of the tree of life is still limited. A multiple correspondence analysis (MCA; the counterpart of principal component analysis for categorical data) of the reactomes [G] of 108 GEMs (Fig. 2c) showed that the clustering of the models by their metabolic functions is strongly related to their phylogeny. MCA also suggested that the differences amongst prokaryotic models are relatively small. By overlaying the 108 models on the tree of life (Fig. 2d) we observed results similar to MCA analysis performed in 2014 (ref.44), namely that network reconstruction efforts have been mainly focused on Proteobacteria, leaving many other phylogenetic branches without any available reconstructions. Although this observation is only based on the 108 models in BiGG, it is clear that the development of GEMs for less-studied organisms may greatly expand the coverage of metabolic pathways and the ‘reactome’ represented by curated GEMs (Fig. 2b). A large-scale effort is needed to establish a global metabolic atlas, with ‘global’ referring to the tree of life.

Evolution of the E. coli GEM

The serial development of E. coli metabolic reconstructions has led to the expansion in the scope and applications of GEMs. Fig. 3 depicts the iterations69–77 of the E. coli GEMs published since 2000 and the changes in the model content. In this section we focus on the development of metabolic models (M models), and ME models shown in Fig. 3 will be discussed in later sections. The first two reconstructions (not shown in Fig. 3) were developed before the E. coli genome was sequenced and were based solely on biochemical knowledge. After the genomic sequence of E. coli K-12 MG1655 was established in 1997 (ref.78), its annotation and new discoveries of metabolic functions led to a series of genome-scale reconstructions of ever increasing scope and content.

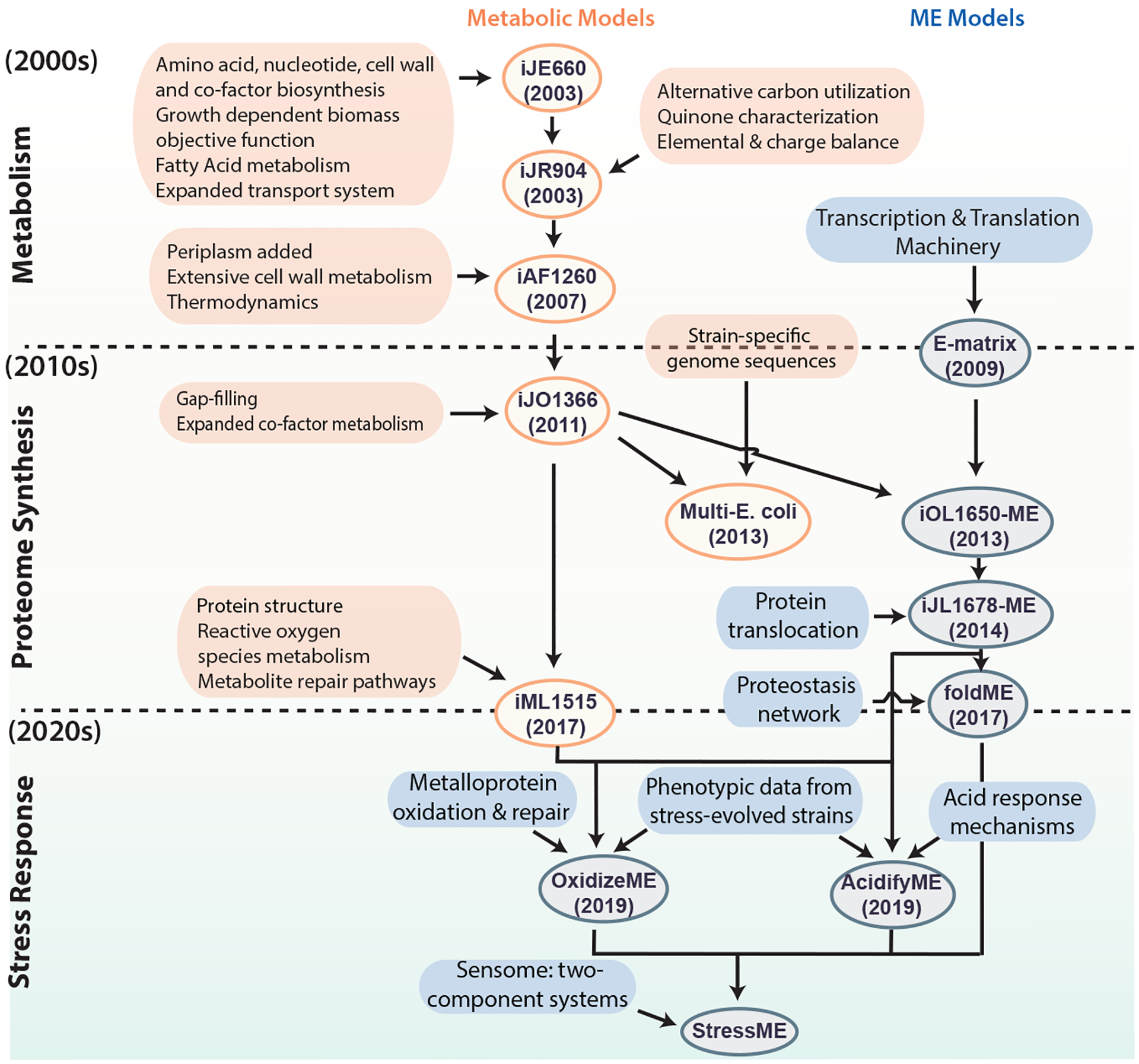

Figure 3:

Historical development of Escherichia coli genome-scale models. Development of existing and potential future genome-scale models (both metabolic, shown in orange, and metabolic and macromolecular expression (ME) models shown in blue) of E. coli. The genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli first appeared in the early 2000s. An increasing scope of biological functions has been incorporated into the model, leading to various generations of the metabolic models as new discoveries were made. In the early 2010s, ME models that incorporate transcription and translation mechanisms emerged. Multiple efforts followed to improve and expand the ME model. Going into the 2020s, extensions of stress response modules have been added to ME models. Future directions involve incorporation of the sensome [G] to form the StressMe model, and the inclusion of toxins, biosynthetic gene clusters and cell cycle. Ovals indicate models, and boxes represent data incorporated to generate the models. According to the naming convention for network reconstructions, model names consist of an ‘i’ for in silico followed by the initials of the person(s) who built the model, and the number of open reading frames accounted for in the reconstruction.

The latest E. coli model, iML1515, now includes 1,515 genes76. iML1515 has comprehensive coverage of metabolic functions integrated with protein structural information, enabling growth simulation on different nutrients for strains of interest as well as an evaluation of mutational impact across strains using structural biology methods76,79,80. iML1515 was used to simulate gene knockouts on 16 different carbon sources and predicted gene essentially across conditions with an accuracy of 93.4% compared with experimental data, highlighting the potential to identify drug targets using GEMs of pathogenic organisms.

In addition, iML1515 was also used to analyze transcriptomics data from 333 experiments with various conditions and provided valuable insight into transcriptional variation across conditions. For example, the three isozymes of aspartate kinase (lysC, metL, and thrA) have variable expression across conditions. iML1515 simulation suggests that when only lysC is expressed, E. coli is unable to synthesis L-threonine, L-methionine, L-isoleucine, biotin, and adenosylmethionine biomass components, which explains why lysC is preferentially expressed in nutrient-rich conditions when these metabolites are available.

We note that of the 4,623 open reading frames annotated on the E. coli K-12 MG 1655 genome sequence, 1,600 are of unknown function (the so-called ‘y-genes’)81, leaving 3,023 genes of known function on which to base a reconstruction. With the 1,515 genes in the latest metabolic network reconstruction, ~50% of the functionally annotated genes are accounted for. The known biochemical functions of the corresponding gene products can now be computationally assessed in the context of the function of all the other gene products. This coverage forms the genetic and biochemical basis for the metabolic systems biology of E. coli.

Thus, the scope of GEM applications has increased with the expansion of metabolic coverage. The early models were used to compute basic phenotypes such as growth rate, by-product secretion, and yield of co-factors. Other applications of E. coli GEMs have been reviewed elsewhere10,11. The most recent GEMs now enable applications such as pan-genome analysis, computation of proteome allocation [G], and the simulation of various stress responses that we will discuss in detail below.

Emerging applications of GEMs

The availability of genome-scale multi-omics data sets is growing rapidly; including whole genome sequences, and transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics data. This calls for the development of tools to interpret and contextualize such data sets. Therefore, to enable direct integration of such data with GEMs, recent model development introduced macromolecular expression into the metabolic models to produce ME models, which allow direct comparison between the simulation and experimental data. Additionally, earlier GEMs were usually developed based on a representative strain from a species, but the availability of multiple genome sequences within a species allows us to develop strain-specific GEMs to explore variation across strains.

In this section, we discuss three new directions in the development of GEMs and their emerging applications; multi-strain analyses that enable investigations into strain-specific variation; ME models that can compute proteome allocation; and simulation of stress responses that facilitate an understanding of complex phenotypes. Other directions in GEM development that have been addressed in other reviews, include, but not limited to the integration of GEMs with structural biology82, modeling of complex communities such as the microbiome83, and tissue or cell-specific models constrained by multi-omics data84.

Multi-strain analysis

With the ever-increasing number of genome sequences, it has become clear that large variations exist in the gene portfolio across strains of a species. In 2005, the concept of the pan-genome — the total list of genes found in all sequenced genomes of strains belonging to a species — was introduced. The pan-genome is composed of a core genome (that is, genes shared by all strains within a species), and an accessory genome (that is, genes present in only a subset of strains)85. Although some species have relatively conserved gene portfolios (known as a closed pan-genome), other species have substantial variability in strain-specific gene portfolios (known as an open pan-genome).

E. coli was shown to have substantial differences in gene portfolios across strains, with as little as ~20% of the total number of genes annotated being shared across the sequenced strains86. The diversity in gene portfolios is thought to be a reflection of adaptation to different microenvironments. Many other microorganisms share this characteristic, including Salmonella spp.87, Staphylococcus aureus88, and Klebsiella pneumoniae89. It has become clear that it is important to understand the broad range of metabolic capabilities encoded by accessory genes, as they could potentially contribute to the pathogenicity and interactions with a human host90.

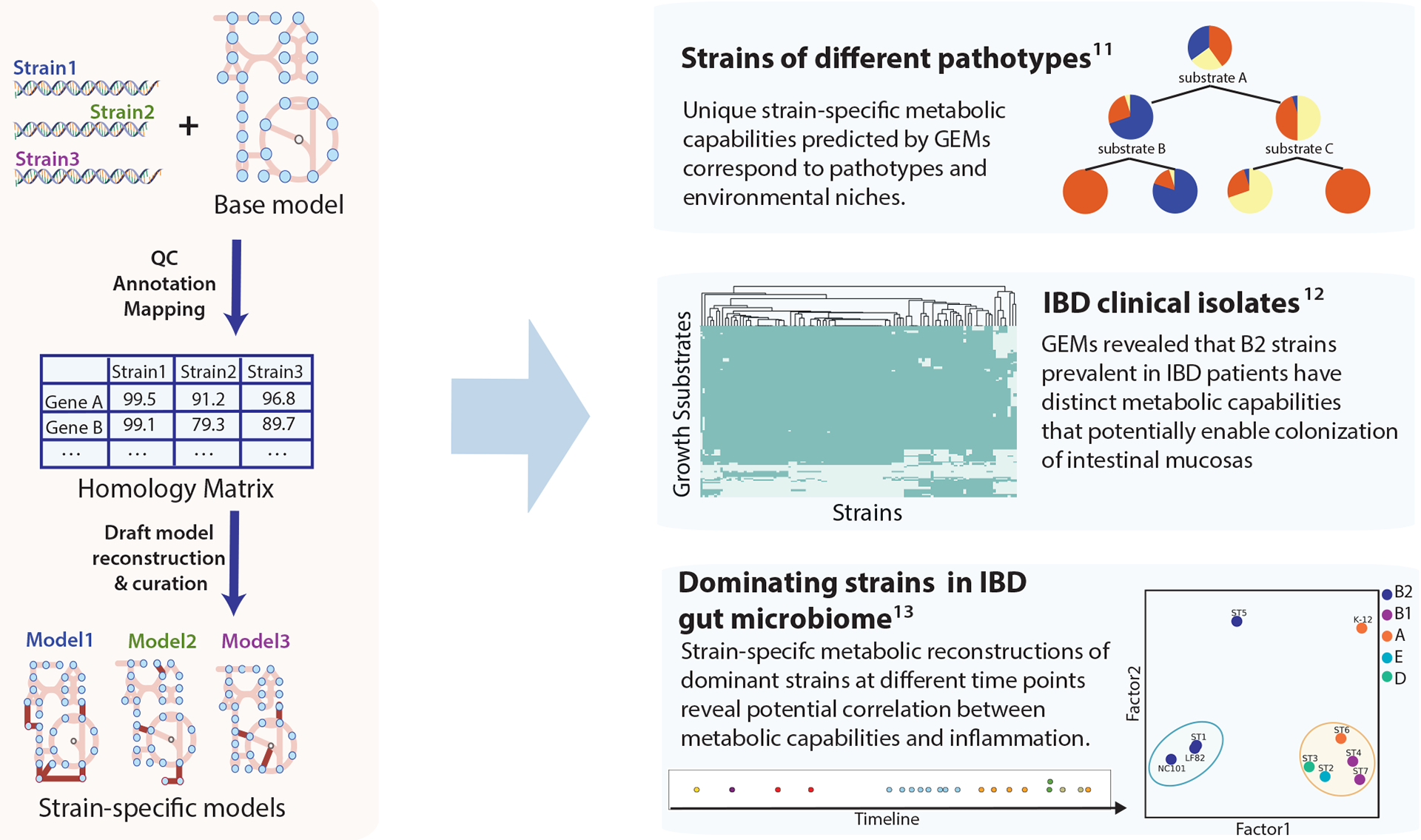

Pan-genome analysis typically refers to comparative analysis of genes across strains. Building GEMs for many strains offers a much deeper analysis based on all the mechanisms that GEMs contain for metabolic processes. The workflow to generate strain-specific models is illustrated in the left panel of Fig. 4. Genomes of strains of interest are mapped to a curated reference reconstruction to generate a homology matrix, which is used to guide the deletion of genes and reactions from the reference model to create draft models. Manual curations are needed to finalize strain-specific GEMs (Fig. 4). The first multi-strain GEM studies from 2013 established GEMs for a set of 55 E. coli and Shigella spp. strains91. By simulating growth capabilities on different nutrient resources, the study predicted strain-specific auxotrophies and unique metabolic capabilities that correspond to their pathotypes and colonization sites. The simulated growth phenotypes separated the strains based on their pathotypes, as most commensal strains were unable to grow on a set of nutrients, such as N-acetyl-D-galatosamine, which supports growth for 100% of extraintestinal pathogenic strains. In addition, 12 of the 55 strains were predicted to be unable to produce at least one essential biomass component, including folate, thiamin, and amino acids from glucose M9 minimal media, some of which are confirmed in the literature.

Figure 4:

Generation of strain-specific Escherichia coli genome-scale models and their application to multi-strain studies. Strain-specific models were generated from genome sequences of strains of interest and a curated reference model. The annotated genome sequences of target strains are mapped to the reference genome sequence to generate the homology matrix that delineates the gene sequence similarity across strains. The homology matrix can be used to create draft models of target strains. These models can then be finalized by manual curation. Strain-specific models were used to reveal variation in metabolic capabilities across different pathotypes, as illustrated in three studies shown on the right. The first multi-strain study of E. coli genome-scale models (GEMs) found metabolic capabilities predicted by GEMs correspond to pathotype and environment. In the second study, comparison of GEMs constructed for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical isolates suggested the possible link between metabolic functions of B2 strains and their prevalence in individuals with IBD. Lastly, GEMs of dominant strains in an individual with IBD revealed the potential correlation between metabolism and inflammation91–93. Panel ‘Strains of different pathotypes’ adapted from ref. 91. Panel ‘IBD clinical isolates’ adapted from ref. 92. Panel ‘Dominating strains in IBD gut microbiome’ adapted from ref. 93.

More recent pan-genome studies of E. coli explored the linkage between metabolism and health outcomes. A study of metabolic capabilities of clinical isolates of E. coli strains from individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Fig. 4)92 compared growth simulation of strain-specific models of clinical isolates and commensal strains, and identified a pathway specific to strains from the B2 phylogroup that are prevalent in individuals with IBD. This pathway is involved in metabolizing the mucus glycan through the action of tagatose bisphosphate aldolase, which potentially aids E. coli strains in the colonization of intestinal mucosa92.

In a separate study utilizing time-series metagenomics data from an individual with IBD (Fig.4)93, we found multiple E. coli strains dominating the microbiome at different time points as inflammation level varied. Strain-specific GEMs were reconstructed for each strain, and the metabolic capabilities delineated by strain-specific GEMs were vastly different across these dominant strains. The models suggest that the strain extracted during the peak inflammation is the most similar to known representative pathogenic strains in IBD, whereas dominant strains extracted from low inflammation time points were more similar to commensal strains. Specifically, the dominant strain present during peak inflammation and known pathogenic strains were predicted to share the capability to grow in a set of substrates, including cellobiose, deoxyribose, and monosaccharides derived from intestinal mucosa, suggesting that strain-specific features are potentially linked to pathogenicity and disease progression.

The application of GEMs for pan-genome analysis is not limited to E. coli. Great potential exists for using GEMs to study pathogens to understand strain-specific features and their association with colonization sites, pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance, and their impact on human health. Several published studies have already utilized strain-specific GEMs to further understand strain-specific characteristics of various microorganisms.

Salmonella spp. were shown to have serovar-specific metabolic traits, including auxotrophies and catabolic pathways that may be associated with adaptations to their colonization sites87. The metabolic capabilities of S. aureus were found to link to pathogenic traits and virulence acquisitions, which can then be used to classify mild versus severe infections94. For example, two S. aureus USA300 isolates were predicted to be the only strains capable of using spermidine as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen94. Spermidine is produced in areas of inflammation and wound healing95, which give these strains the opportunity to cause skin infection. A study of K. pneumoniae strains with antibiotic resistance phenotypes suggested differential utilization of nitrogen sources may help discriminate between antibiotic resistance phenotypes96. Similar studies have also been performed for other species: strain-specific Acinetobacter baumannii97 GEMs revealed the significant variation in lipopolysaccharide across strains; GEMs of Leptospira spp. delineated the differences in lysine metabolism between pathogenic and commensal Leptospira spp.98; and Pseudomonas putida strain-specific models reflected the diverse metabolic capabilities across strains due to variations in environmental niches99.

For a large number of sequenced genomes (over 1,000 strains), it has been shown that the gene portfolio of individual strains cannot only be characterized in terms of the presence or absence of a gene, but also in terms of the particular allele of the gene. Thus, a field of ‘alleleomics’ may have emerged. Alleleomic analysis was shown to be valuable for studying organisms with closed pan-genomes. Using a GEM-based machine learning classifier, one study100 was able to predict antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, while enabling a biochemical interpretation of the genotype–phenotype map. Specifically, through investigation of key flux states discriminating between M. tuberculosis strains that are resistant and susceptible to pyrazinamide, the authors correctly identified pncA and ppsA alleles as major genetic determinants, which had been reported in the literature, and proposed new hypotheses that ansP2 mutants may potentially contribute to resistance through L-aspartate-based modulation of the coenzyme A pool.

A semi-automated protocol for generating strain-specific models from a collection of strain-specific genome sequences has been made available2 to aid researchers in reconstructing and utilizing the strain-specific GEMs. This protocol details the major stages involved in strain-specific model generation and curation, accompanied by easy-to-follow tutorials in python notebooks to ensure strain-specific GEMs are accessible to researchers interested in applying them to different organisms. The protocol does not require advanced coding skills.

The ME model

The demonstrated predictive ability and broad applications of GEMs of metabolism (M models) challenged their boundaries and drove further development. M models can be improved by increasing the number of constraints or by expanding their scope in terms of cellular processes represented. For instance, a framework that incorporates enzyme abundances as constraints in metabolic models substantially reduces the solution space, but requires enzyme turnover numbers (so-called kcat values)101. Researchers have also developed models that integrate multiple layers (metabolism, transcription, and signal transduction) of the bacterial organism using multi-omics data102.

Expanding the scope of GEMs to include proteome allocation.

A major effort focused on expanding M models to include a genome-scale account of translation and transcription, leading to so-called ME models (for metabolism and expression). ME models are more fundamental than proteome or enzyme constrained models, as they explicitly incorporate a full reconstruction of the pathways that constitute transcription and translation in addition to metabolism, enabling the simulation of proteome composition. Thus, the constraints on the proteome are generated by the ME model itself as a part of computing a particular phenotypic state. The general formulation of ME models is depicted in Fig. 5. Like M models, ME models are solved using flux balances. ME models can thus be used to compute the proteome allocation between growth conditions of a strain (proximal causation [G]), or evolutionary adaptation to a new condition (distal causation [G]), which greatly expand the range of biological functions and behaviors over a metabolic model.

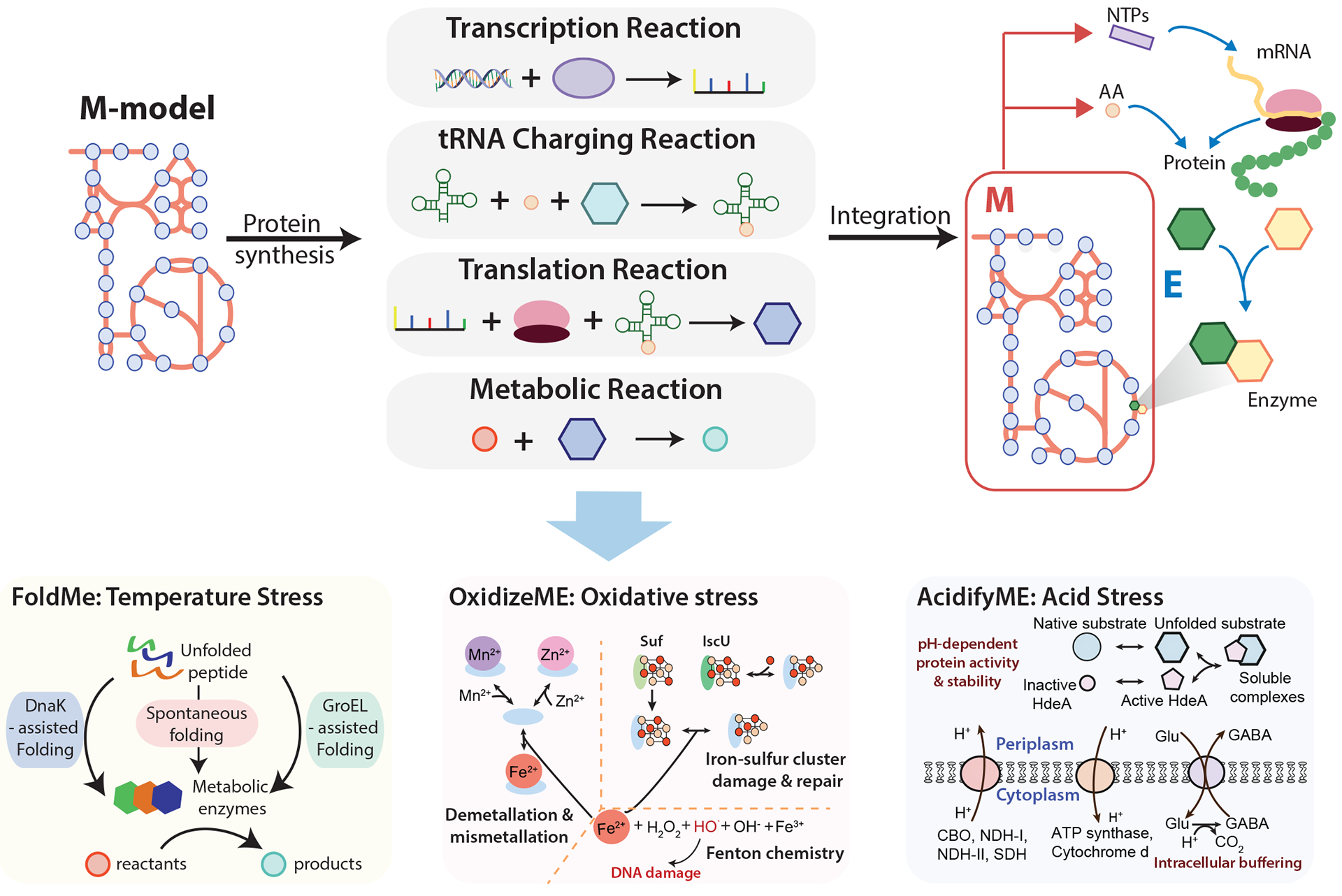

Figure 5:

General formulation of a metabolic and macromolecular expression model and its application to the study of stress response. Metabolic and macromolecular expression (ME) models are generated through the integration of M models and protein synthesis pathways including transcription, tRNA charging, and translation. Therefore, the ME model describes the biosynthesis of proteins and their roles in catalyzing the metabolic reactions. Stress-specific response mechanisms are integrated with the E. coli ME model to produce stress-specific ME models: FoldME, OxidizeME, and AcidifyME. FoldME models respond to temperature stress through the incorporation of chaperone-mediated (GroEL or DnaK) or spontaneous folding pathways. OxidizeME simulates the response to oxidative stress through the inclusion of oxidation and demetallation in metalloproteins, iron-sulfur cluster cofactor damage and repair, and DNA damage. AcidifyME models the mechanisms related to acid stress, including pH-dependent protein activity and stability, membrane composition, and intracellular buffering. CBO, cytochrome bo terminal oxidase; NDH-I, NADH dehydrogenase I; NDH-II, NADH dehydrogenase II; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; Glu, glutamate; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; NTPs, nucleoside triphosphates. FoldME panel adapted from ref. 127. OxidizeME panel adapted from ref. 129.

Building ME models.

The first large-scale network reconstructed to describe the transcriptional and translational machinery in E. coli appeared in 2009(ref.103). The reconstruction was mathematically described by the expression matrix [G] (E matrix) representing 13,694 biochemical reactions that delineate the expression of genes and protein synthesis in E. coli. The E matrix incorporated all the functional components (proteins, nucleotides, etc.) and pathways, known at the time, underlying translation and transcription, including biosynthesis, modification, and degradation of RNA and protein complexes. This reconstruction was also converted to a computational model to enable quantitative integration of omics data and simulation of phenotypic states; for example, the model predicted the ribosome production accurately under different conditions without any parameterization.

A ME model is an integration of the E matrix with a metabolic model (Fig. 5). The M model describes the metabolic function and the E matrix delineates the macromolecular expression pathways. M and E are combined through their shared metabolites and coupling constraints; that is, macromolecules are produced at a rate proportional to the rate of enzyme dilution to daughter cells (growth rate), proportional to the activity of the metabolic reaction, and inversely proportional to the enzyme turnover rate (kcat). By incorporating the E matrix into an M model, ME models enable the calculation of the cellular cost of enzyme synthesis, which is coupled to the reaction they catalyze. The maximum growth rate in ME models is thus solved by iteratively plugging in increasing growth rate values until the maximum value that produces a solvable model is found.

Towards ‘proteometrics’.

The ME model’s formulation essentially produces an econometric model of cellular functions. Each cell has a limited space for protein to perform its metabolic and growth functions (the size of the E. coli proteome is estimated to be about 2.5 million protein molecules per cell104). By assigning a ‘capital expense’ (that is, investment in proteome synthesis — the hardware of the cell) to each metabolic function, the ME model provides a framework to determine the most protein-cost effective way for the cell to carry out its required functions. A consequence of this ME model characteristic is that the substrate uptake rates do not need to be defined a priori, as is the case for M models. Optimal substrate uptake rates are determined by the optimal protein composition. As ME models are econometric in the sense that they compute the best ‘capital expenditures’ (that is, proteome allocation) and ‘operating expenses’ (that is, best metabolic state) to achieve a particular phenotypic state, one might think of them as being ‘proteometric’ models.

Whereas M model solutions fall within a multidimensional solution space (that is, there are alternative solutions for any optimal objective value), ME model solutions at their maximum feasible growth rate are effectively unique. Furthermore, the ME model not only predicts a cell’s maximal growth rate and corresponding metabolic fluxes, but also computes the optimal proteome allocation and gene product expression level. The ME model basically represents molecular biology and biochemistry on a genome-scale, and through its mathematical representation, allows the computation of its fully balanced operation. However, it is worth noting that although the ME model covers both transcription and translation, it does not model the regulatory processes.

ME models are based on optimality principles with the implicit assumption that regulation will produce the computed phenotypic state. This characteristic opens up the ability to address a fundamental question, namely, do the evolved transcriptional regulatory processes reflect optimality principles that can be represented in a ME model? In other words, can evolution and adaptation-produced outcomes be represented by the appropriate statement of an optimal function?

Experience with specific ME models and their applications.

A ME model was first reconstructed for Thermotoga maritima, which has a genome with 1,877 annotated genes. The ME model for T. maritima was developed as a prototype, returned accurate predictions of cellular composition and gene expression, and showed potential for aiding in the discovery of new regulons and genome annotation105. Growth simulation identified a set of genes with strong differential expression when T. maritima grows in minimal medium with L-arabinose or cellobiose as the carbon sources, suggesting the presence of transcriptional regulation. The predicted differentially-expressed genes led the authors to discover potential transcription factor binding motifs that are similar to known motifs in other organisms, highlighting how ME models can guide discovery of new regulons.

A year later, a ME model was built for E. coli through the integration of the E matrix with the most recent M model available75 (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). This ME model was able to better predict some phenotypes than M models due to its expanded scope and additional constraints. For example, unlike previous GEMs, the predicted growth rate by the E. coli ME model has a nonlinear relationship with the substrate uptake rate, which is consistent with the long-standing empirical models of microbial growth. ME model simulation suggests that under nutrient-limited conditions, growth is constrained by substrate availability, whereas under nutrient-excess conditions, growth is limited by internal constraints on protein synthesis and catalysis. ME models can also predict the maximum batch growth rate and optimal substrate uptake rate that closely matches experimental data from laboratory evolved strains.

Subsequent efforts focused on the improvement of several aspects of the E. coli ME models (Fig. 3). One study added the protein translocation pathways across the inner membrane, leading to four cellular compartments and membrane constraints that reflect the cell morphology106. Efforts to refine numerical values for enzyme turnover number (kcat) through machine learning methods107 were undertaken, and a reformulation of the E. coli ME model computations by grouping major cellular processes and implementing explicit coupling constraints drastically reduced the size of the stoichiometric matrix and computational solving time108.

The expanded predictive capability of ME models motivated their construction for other microorganisms of interest. The development of a ME model for Clostridium ljungdahlii enabled the prediction of overflow metabolism [G] that shed light onto media optimization strategies for bioproduction109. The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is the only known CO2-fixing pathway coupled to energy conservation in Clostridium ljungdahlii, and trace metals are crucial in this pathway. The ME model was able to evaluate the impact of trace metals on metabolite secretion as the model incorporated protein modifications accounting for these metals. Specifically, simulation results suggested that removing nickel from the media may reduce acetate production, leading to ethanol production as the main fermentation product, providing valuable insights to bioproduction design strategies. A summary of published ME models and their characteristics can be found in Table 1. Additional species-specific models are under development. It is worth noting that another ME model formulation has been developed110 to model metabolism, gene expression, and thermodynamic constraints, enabling new insights into the diauxic behavior in bacteria111.

Table 1.

Summary of published metabolic and macromolecular expression ME models.

| Model | Organism | Coverage | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. maritima- ME105 | Thermotoga maritima | Metabolism, macromolecular synthesis, post-transcriptional modification and dilution to daughter cells | Accurately predicted cellular composition and gene expression; Enabled new regulon discovery and genome annotation |

| iOL1650-ME124 | Escherichia. coli | 1,650 genes, 1,295 protein complexes accounting for metabolism, gene expression and macromolecular synthesis | Accurate prediction of multi-scale phenotypes; Revealed the importance of proteomic constraints on growth, by-product secretion, metabolic flux, uptake rates and optimal |

| iJL1678-ME106 | E. coli | Incorporated four compartments, (cytoplasm, periplasm, inner, and outer membranes) translocation pathways, membrane constraints in previous iOL1650- ME | Enabled prediction of enzyme abundances and their cellular location; Predicted impact of perturbations such as membrane crowding and enzymatic efficiency |

| iJL1678b-ME108 | E. coli | Compared to iJL1678- ME: reformulated coupling constraints; groupedlumped major cellular processes; and iIncluded non-equivalent changes | Significantly reduced free variables and solve time; Increased accuracy in model prediction |

| iJL965-ME109 | Clostridium ljungdahlii | 965 genes, 735 protein complexes accounting for central metabolism, transcription, translation, macromolecule modifications, and translocation | Produced accurate prediction of fermentation profiles, yielding deep interpretation of overflow metabolism products, gene expression, and usage of cofactors and metals |

Thus far, ME models have only been developed for a few microorganisms besides E. coli due to the challenges in computational resources and model development. However, the reconstruction process of ME models has now been made easier with the development of the software framework COBRAme108, a python [G] package that simplifies the process of reconstructing and analyzing ME models. With the use of COBRAme, draft ME models can be constructed from: a high-quality M model; a standard GenBank genome annotation file; curated enzyme subunit stoichiometries; mappings of enzyme complexes to metabolic reaction; and enzyme turnover rates. The ME model can also be made more sophisticated by incorporating enzyme prosthetic group information, post-transcriptional or post-translational modifications, protein translocation information, transcription unit information, and other cellular processes. Once reconstructed, researchers are able to edit and simulate ME models using COBRAme, which uses a software architecture mirrored after popular GEM analysis tools like COBRApy. The streamlined computational and analysis pipelines in COBRAme have enabled a substantially expanded range of computational predictions, as we will discuss in the following section.

It is worth mentioning that assembling two data types mentioned above — enzyme complex stoichiometry and enzymatic turnover rates — can present bottlenecks when constructing ME models. For well-studied microorganisms, assembling enzyme complex compositions can be aided with the use of expertly curated organism knowledge bases such as MetaCyc112. Alternatively, elucidating enzyme turnover rates on a systems level is an area of ongoing research113 that has recently been facilitated by the use of machine learning and omics datasets107,114. Future work is necessary to determine the sensitivity of ME models to these parameters and the degree to which these quantities may be conserved across microorganisms.

Beyond ME-models lies many additional cellular processes. Whole-cell models of the human pathogen Mycoplasma genitalium115, Saccharomyces cerevisiae116 and E. coli117 have been developed. The whole-model is composed of independent modules describing particular cellular processes, such as cell replication, transcriptional regulation, and DNA maintenance. Different from ME models, whole-cell models are computed by simulating each module over a short time increment. Additionally, the enzyme abundances in whole-cell models are variables determined by the previous simulation increment, whereas enzymes in ME models are directly imposed as metabolites in their metabolic reactions, which ensures that protein limitation has a dominant role in defining the metabolic flux state.

From growth to stress responses

The scope and range of prediction continues to grow as the coverage of cellular processes in GEMs expands118–123. Whereas metabolic models enable predictions of growth on different nutrients, metabolite secretion, and auxotrophy, ME models have added capabilities to simulate the proteome allocation and RNA-to-protein mass ratio for a given phenotype124, and differential gene expression levels across environmental shifts105.

Combined with genome-scale multi-omics data, ME models have become useful tools that provide a mechanistic and systems-level understanding of E. coli. The integration of ME models and global proteomics data was used to characterize the unused proteome, that is, protein molecules that are not utilized or underutilized for cellular growth (although they might be synthesized), and protein molecules that are present in excess in E. coli. By comparing the number of protein molecules needed for growth predicted by the ME model with quantitative proteomics data, the authors identified proteins that were not used towards growth. The unused proteins were shown to decrease with increasing growth rate, suggesting that there exists a fitness tradeoff between growth rate and the unused proteins encoding stress- and nutrient- preparedness functions. This tradeoff possibly conveys fitness benefits in changing environments while taking resources away from growth125.

The ME model formulation can demand that translated proteins are folded, equipped with the proper prosthetic groups, and assembled into protein complexes in order to carry out their enzymatic function. Modeling the proteome in this level of detail inherently provides a robust link between metabolism and the biosynthesis of functional enzyme complexes126. ME models therefore enable genome-scale investigations into the cellular response to any dysfunction in protein synthesis or maintenance, such as those that can occur when cells experience stress conditions. Thus, several extensions of ME models have recently been developed to describe stress response and mitigation functions in mechanistic detail127–129. Taking E. coli as an example, reconstructions of known stress response mechanisms have been integrated with ME models to form a new generation of models: FoldME128, OxidizeME129, and AcidifyME127, which simulate the response to thermal, oxidative, and low pH stress, respectively (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). Each of these environmental stresses are relevant to the lifestyle of E. coli, particularly when existing in a host organism.

The FoldME model extension expands the ME model to include peptide folding (chaperone-mediated or spontaneous) while taking into account basic biochemical properties such as protein kinetic folding rates and thermostability. By detailing these proteostatic mechanisms, FoldME is capable of describing protein folding, denaturing, and catalytic activity as a function of temperature on a genome scale. Applying FoldME produced multi-scale predictions for cellular adaptations under high temperature by introducing the unfolded state of the proteins and in vivo protein folding as a competition between spontaneous folding and DnaK or GroEL-assisted folding (Fig. 5). FoldME faithfully recapitulated the temperature dependent growth rate and changes in protein abundances128 — as the optimal growth temperature for E. coli is exceeded, more proteome denatures, forcing more chaperones to be expressed, and therefore less of the total proteome is available for growth functions.

Another universal stress that may hinder cell growth is reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidative damage in a cell can manifest in multiple ways, including oxidation and demetallation of the mononuclear iron cofactors in metalloproteins, iron-sulfur cluster cofactor damage, and DNA damage. The OxidizeME extension was constructed by incorporating pathways involved in these ROS-based damage and repair processes (Fig. 5). Furthermore, structural biology was applied to determine which proteins, based on the position of metallic cofactors in the 3D structure of the enzyme, were most susceptible to ROS damage. As ME models explicitly require the presence of the proper unimpaired cofactors in order for an enzyme to possess any catalytic function, the model could assess the systems-level effects of oxidative damage and repair in E. coli. OxidizeME correctly predicted the phenotypes under oxidative stress, such as aromatic amino acid auxotrophy, carbon-source dependent ROS sensitivity, and stress-specific differential gene expression, and traced the possible mechanisms involved in iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis129.

Such an effort was also extended to pH stress to elucidate the changes in cellular responses under acidic conditions. AcidifyME simulates pH-dependent membrane lipid fatty acid composition, periplasmic protein stability and periplasmic chaperone protection, and membrane protein activity under low pH (Fig. 5). It recapitulated differential gene expression under acid conditions, enabled a systematic and mechanistic understanding of acid stress response, and most importantly suggested potential intervention strategies127. For example, model simulation suggests that knocking out hdeB, the only known periplasmic chaperone in E. coli, would result in no growth under acidic conditions. If such predictions can be verified by experimental studies, HdeB could become a promising antimicrobial target to inhibit E. coli growth under acidic environments such as the human digestive tract.

Conclusions

The first annotated genome sequences appeared in the mid to late 1990s. With metabolism being a well characterized cellular process, a comprehensive list of metabolic genes was identified on these newly sequenced genomes. The recognition that the biochemical functions of enzymes could be defined led to a formulation of a process for network reconstruction at the genome-scale. In other words, one could, in principle, reconstruct the entire metabolic network from an annotated genome sequence. In practice, reconstruction technology has advanced over the past 20 years to include protocols to deal with issues arising from incomplete genome annotation and the development of quality control standards.

Reconstructions are knowledge-bases that have many uses. One use detailed here is the conversion of knowledge into computational models that represent the functions of an ‘in silico’ cell whose properties can be computationally simulated. These models open up the comparison between characterization of what is known about an organism (that is, the GEM) and how the organism actually functions. As we do not have complete knowledge of any organism, the difference between the two (observed and simulated functions) has proved to be a guide to the discovery of missing parts and an understanding of integrated cellular functions.

The computation of biological functions needs to represent proximal and distal causation. GEMs formulated through a constraint-based formalism can represent both, and thus simulate dual causation130. Proximal causation can be comprehensively detailed through the inclusion of increasingly accurate biophysical representations of cellular processes. This approach has led to the formulation of whole-cell models of M. genitalium115, S. cerevisiae116, and E. coli117 to describe in increasing biophysical detail their molecular components and interactions115. These models become increasingly specific to a particular strain functioning in particular environments.

Distal causation can be pursued through adaptive laboratory evolution and through pan-genomics. Here, the differences between strains and species are considered, and the question of interest is how natural selection leads to adaptation and longer-term evolution. Reconstruction and GEMs are used as tools to compare gene portfolios with the corresponding phenotypic potential and matching these to selection pressures. The most comprehensive description of the formulation, underlying philosophy, and use of constraint-based models is found in a recent textbook131.

As reviewed in this article, GEMs have developed over 20 years, starting with metabolism then expanding in scope to include transcription and translation and stress functions. They will continue to grow in their scope and accuracy in the representation of known cellular functions. Comprehensive representations of two-component systems and the structural proteome76,79 are now possible, as are cell division mechanisms, whose inclusion will refine the models from representations of populations to individual cells. This process will continually improve our understanding of how microbial cells function and evolve and will likely one day assist with the design of synthetic genomes.

BOX 1 |. Why build computational models?

Computational models describe a system through a mathematical formalism enabling the study of its behavior through simulation. Models are prevalent in the physical sciences, but are less common in biology. The motivation for building models can be broken down into five categories133.

Organize disparate information into a coherent whole

Network reconstructions represent a formal organization of knowledge that can subsequently be converted into computational models. Genome-scale models (GEMs) enable systems-level understanding and analysis, and produce predictions based on the scope, coverage, and quality of the underlying reconstruction44,68.

Identify important components and interactions in a complex system

An early use of GEMs was to compute gene essentiality72,134. For a poorly characterized organism, Geobacter sulfurreducens, GEMs produced a deep understanding of acetate uptake, acetate activation, and altered amino acid metabolism135.

Make new discoveries

GEMs can be used to simulate perturbation to a metabolic system to identify essential metabolites and to find its structural analogues as candidate drugs that inhibit the enzymes that degrade the metabolite136. GEMs have enabled designs of growth-coupled methylation systems137.

Fill in knowledge gaps

GEM prediction of ‘no growth’ under a condition where the organism experimentally grows is called a ‘false negative’ prediction, which usually is a result of a missing component in the GEM. Gap-filling procedures138–140 and other methods141 were developed to address this issue, driving discoveries and making important corrections in conventional wisdom.

Understand the essential and qualitative features

Qualitative features are important for complex systems. For example, global proteomics data and GEMs helped identify the fear-greed trade-off in E. coli growth125. E. coli was shown to have nearly half of the proteome mass unused in certain environments. This ‘unused’ proteome is involved in nutrient- and stress-preparedness functions that may convey fitness benefits in changing environments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM057089 and Novo Nordisk Foundation Grant NNF10CC1016517. Some figures were adapted from previously published figures, here we acknowledge the original authors of these figures and thank them for their contributions: J. M. Monk (Fig. 3), L. Yang (Fig. 5), K. Chen (Fig. 5), B. Du (Fig. 5) and A. Bordbar (Fig. 1).

Glossary

- Reactome

All the reactions involved in genome-scale models (or a certain model of interest). Each base unit is a reaction, and the entities are metabolites involved in the reactions, such as proteins, nucleic acids and small molecules.

- Proteome allocation

Proteome is the entire set of proteins expressed by an organism at a certain time. Proteome allocation is the partition of proteomics resources into different functions to fulfil the organism’s need at the given condition.

- Proximal causation

Proximal causation explains traits/events (such as change in proteome allocation) in terms of immediate physiological or environmental factors

- Distal causation

Distal causation explains traits/events (such as change in proteome allocation) in terms of evolutionary forces acting on them.

- Expression matrix

Expression matrix (E matrix) is a matrix that describes all components (including DNA, mRNA, proteins, and metabolites) and reactions that are involved in the transcriptional and translational machinery in the organism of interest.

- Overflow metabolism

Overflow metabolism refers to when cells incompletely oxidize their substrate (which yields less energy), instead of using the more energetically-efficient respiratory pathways to completely oxidize their substrates, even when oxygen is available

- Python

Python is an interpreted, general-purpose programming language that is widely used in computational biology

- Sensome

Sensome refers to the components (such as genes and proteins) in an organism or cell that are involved in sensing the changes in the environment.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Microbiology thanks María Suárez Diez, Sara Moreno Paz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Thiele I & Palsson BØ A protocol for generating a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. Nat. Protoc 5, 93–121 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A detailed protocol to reconstruct a GEM from a genome sequence.

- 2.Norsigian CJ, Fang X, Seif Y, Monk JM & Palsson BO A workflow for generating multi-strain genome-scale metabolic models of prokaryotes. Nat. Protoc (2019) doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0254-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A semi-automated workflow to generate strain-specific GEMs from a curated reference model.

- 3.Price ND, Reed JL & Palsson BØ Genome-scale models of microbial cells: evaluating the consequences of constraints. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2, 886–897 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis NE, Nagarajan H & Palsson BO Constraining the metabolic genotype–phenotype relationship using a phylogeny of in silico methods. Nat. Rev. Microbiol (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanehisa M & Goto S KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feist AM & Palsson BO The biomass objective function. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 13, 344–349 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orth JD, Thiele I & Palsson BØ What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol 28, 245 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A primer that thoroughly explains flux balance analysis and its applications.

- 8.Ebrahim A, Lerman JA, Palsson BO & Hyduke DR COBRApy: COnstraints-Based Reconstruction and Analysis for Python. BMC Syst. Biol 7, 74 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heirendt L et al. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA Toolbox v.3.0. Nat. Protoc 14, 639–702 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feist AM & Palsson BØ The growing scope of applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions using Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 659–667 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCloskey D, Palsson BØ & Feist AM Basic and applied uses of genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol 9, 661 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bordbar A, Monk JM, King ZA & Palsson BO Constraint-based models predict metabolic and associated cellular functions. Nat. Rev. Genet 15, 107–120 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien EJ, Monk JM & Palsson BO Using Genome-scale Models to Predict Biological Capabilities. Cell 161, 971–987 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu C, Kim GB, Kim WJ, Kim HU & Lee SY Current status and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Genome Biol 20, 121 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oberhardt MA, Palsson BØ & Papin JA Applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. Molecular Systems Biology vol. 5 320 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazumdar V, Snitkin ES, Amar S & Segrè D Metabolic network model of a human oral pathogen. J. Bacteriol 191, 74–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry CS, Jankowski MD, Broadbelt LJ & Hatzimanikatis V Genome-scale thermodynamic analysis of Escherichia coli metabolism. Biophys. J 90, 1453–1461 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navid A & Almaas E Genome-level transcription data of Yersinia pestis analyzed with a new metabolic constraint-based approach. BMC Syst. Biol 6, 150 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motter AE, Gulbahce N, Almaas E & Barabási A-L Predicting synthetic rescues in metabolic networks. Mol. Syst. Biol 4, 168 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montagud A, Navarro E, Fernández de Córdoba P, Urchueguía JF & Patil KR Reconstruction and analysis of genome-scale metabolic model of a photosynthetic bacterium. BMC Syst. Biol 4, 156 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahadevan R, Edwards JS & Doyle FJ 3rd. Dynamic flux balance analysis of diauxic growth in Escherichia coli. Biophys. J 83, 1331–1340 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastings J et al. Multi-Omics and Genome-Scale Modeling Reveal a Metabolic Shift During C. elegans Aging. Front Mol Biosci 6, 2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan N et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics analysis-guided metabolic engineering of Propionibacterium acidipropionici for improved propionic acid production. Biotechnol. Bioeng 115, 483–494 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgard AP, Pharkya P & Maranas CD Optknock: a bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng 84, 647–657 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hefzi H et al. A Consensus Genome-scale Reconstruction of Chinese Hamster Ovary Cell Metabolism. Cell Syst 3, 434–443.e8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cautha SC et al. Model-driven design of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae platform strain with improved tyrosine production capabilities. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 46, 221–226 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAnulty MJ, Yen JY, Freedman BG & Senger RS Genome-scale modeling using flux ratio constraints to enable metabolic engineering of clostridial metabolism in silico. BMC Syst. Biol 6, 42 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardoso JGR, Andersen MR, Herrgård MJ & Sonnenschein N Analysis of genetic variation and potential applications in genome-scale metabolic modeling. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 3, 13 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folger O et al. Predicting selective drug targets in cancer through metabolic networks. Mol. Syst. Biol 7, 501 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guzmán GI et al. Model-driven discovery of underground metabolic functions in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 929–934 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar M, Ji B, Zengler K & Nielsen J Modelling approaches for studying the microbiome. Nat Microbiol 4, 1253–1267 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuñiga C et al. Environmental stimuli drive a transition from cooperation to competition in synthetic phototrophic communities. Nat Microbiol 4, 2184–2191 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zomorrodi AR & Maranas CD OptCom: a multi-level optimization framework for the metabolic modeling and analysis of microbial communities. PLoS Comput. Biol 8, e1002363 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stolyar S et al. Metabolic modeling of a mutualistic microbial community. Mol. Syst. Biol 3, 92 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang K et al. Genome-scale dynamic modeling of the competition between Rhodoferax and Geobacter in anoxic subsurface environments. ISME J 5, 305–316 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harcombe WR et al. Metabolic resource allocation in individual microbes determines ecosystem interactions and spatial dynamics. Cell Rep 7, 1104–1115 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zomorrodi AR & Segrè D Genome-driven evolutionary game theory helps understand the rise of metabolic interdependencies in microbial communities. Nat. Commun 8, 1563 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelezniak A et al. Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 6449–6454 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhury S & Fong SS Computational Modeling of the Human Microbiome. Microorganisms 8, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy R & Borenstein E Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 12804–12809 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mardinoglu A et al. Genome-scale metabolic modelling of hepatocytes reveals serine deficiency in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Commun 5, 3083 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mardinoglu A & Nielsen J Systems medicine and metabolic modelling. J. Intern. Med 271, 142–154 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards JS & Palsson BO Systems properties of the Haemophilus influenzaeRd metabolic genotype. J. Biol. Chem (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monk J, Nogales J & Palsson BO Optimizing genome-scale network reconstructions. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 447–452 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendoza SN, Olivier BG, Molenaar D & Teusink B A systematic assessment of current genome-scale metabolic reconstruction tools. Genome Biol 20, 158 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satish Kumar V, Ferry JG & Maranas CD Metabolic reconstruction of the archaeon methanogen Methanosarcina Acetivorans. BMC Syst. Biol 5, 28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benedict MN, Gonnerman MC, Metcalf WW & Price ND Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and hypothesis testing in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A. J. Bacteriol 194, 855–865 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson JR et al. Genome-wide gene expression and RNA half-life measurements allow predictions of regulation and metabolic behavior in Methanosarcina acetivorans. BMC Genomics 17, 924 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheikh K, Förster J & Nielsen LK Modeling Hybridoma Cell Metabolism Using a Generic Genome~Scale Metabolic Model of Mus musculus. Biotechnol. Prog (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu H et al. A consensus S. cerevisiae metabolic model Yeast8 and its ecosystem for comprehensively probing cellular metabolism. Nat. Commun 10, 3586 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Oliveira Dal’Molin CG & Nielsen LK Plant genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and modelling. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 24, 271–277 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mintz-Oron S et al. Reconstruction of Arabidopsis metabolic network models accounting for subcellular compartmentalization and tissue-specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 339–344 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung CYM et al. A method for accounting for maintenance costs in flux balance analysis improves the prediction of plant cell metabolic phenotypes under stress conditions. Plant J 75, 1050–1061 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thiele I et al. A community-driven global reconstruction of human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swainston N et al. Recon 2.2: from reconstruction to model of human metabolism. Metabolomics 12, 109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunk E et al. Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 272–281 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar A, Suthers PF & Maranas CD MetRxn: a knowledgebase of metabolites and reactions spanning metabolic models and databases. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henry CS et al. High-throughput generation, optimization and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models. Nat. Biotechnol 28, 977–982 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machado D, Andrejev S, Tramontano M & Patil KR Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 7542–7553 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agren R et al. The RAVEN toolbox and its use for generating a genome-scale metabolic model for Penicillium chrysogenum. PLoS Comput. Biol 9, e1002980 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang H et al. RAVEN 2.0: a versatile toolbox for metabolic network reconstruction and a case study on Streptomyces coelicolor doi: 10.1101/321067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arkin AP et al. KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 566–569 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Norsigian CJ et al. BiGG Models 2020: multi-strain genome-scale models and expansion across the phylogenetic tree. Nucleic Acids Res (2019) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glont M et al. BioModels: expanding horizons to include more modelling approaches and formats. Nucleic Acids Res 46, D1248–D1253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moretti S et al. MetaNetX/MNXref--reconciliation of metabolites and biochemical reactions to bring together genome-scale metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D523–D526 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pabinger S et al. MEMOSys 2.0: an update of the bioinformatics database for genome-scale models and genomic data. Database 2014, bau004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noronha A et al. The Virtual Metabolic Human database: integrating human and gut microbiome metabolism with nutrition and disease. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D614–D624 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lieven C et al. MEMOTE for standardized genome-scale metabolic model testing. Nat. Biotechnol (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0446-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Varma A & Palsson BO Metabolic Capabilities of Escherichia coli II. Optimal Growth Patterns. J. Theor. Biol 165, 503–522 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pramanik J & Keasling JD Stoichiometric model of Escherichia coli metabolism: incorporation of growth-rate dependent biomass composition and mechanistic energy requirements. Biotechnol. Bioeng 56, 398–421 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pramanik J & Keasling JD Effect of Escherichia coli biomass composition on central metabolic fluxes predicted by a stoichiometric model. Biotechnol. Bioeng 60, 230–238 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Edwards JS & Palsson BO The Escherichia coli MG1655 in silico metabolic genotype: its definition, characteristics, and capabilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 5528–5533 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reed JL, Vo TD, Schilling CH & Palsson BO An expanded genome-scale model of Escherichia coli K-12 (iJR904 GSM/GPR). Genome Biol 4, R54 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feist AM et al. A genome-scale metabolic reconstruction for Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 that accounts for 1260 ORFs and thermodynamic information. Mol. Syst. Biol 3, (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Orth JD et al. A comprehensive genome~scale reconstruction of Escherichia coli metabolism—2011. Mol. Syst. Biol 7, 535 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Monk JM et al. iML1515, a knowledgebase that computes Escherichia coli traits. Nat. Biotechnol 35, 904–908 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The most up-to-date genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli.

- 77.Archer CT et al. The genome sequence of E. coli W (ATCC 9637): comparative genome analysis and an improved genome-scale reconstruction of E. coli. BMC Genomics 12, 9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blattner FR et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277, 1453–1462 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brunk E et al. Systems biology of the structural proteome. BMC Syst. Biol 10, 26 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mih N et al. ssbio: a Python framework for structural systems biology. Bioinformatics 34, 2155–2157 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ghatak S, King ZA, Sastry A & Palsson BO The y-ome defines the 35% of Escherichia coli genes that lack experimental evidence of function. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 2446–2454 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mih N & Palsson BO Expanding the uses of genome-scale models with protein structures. Mol. Syst. Biol 15, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Magnúsdóttir S & Thiele I Modeling metabolism of the human gut microbiome. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 51, 90–96 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Opdam S et al. A Systematic Evaluation of Methods for Tailoring Genome-Scale Metabolic Models. Cell Syst 4, 318–329.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rouli L, Merhej V, Fournier P-E & Raoult D The bacterial pangenome as a new tool for analysing pathogenic bacteria. New Microbes New Infect 7, 72–85 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lukjancenko O, Wassenaar TM & Ussery DW Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes. Microb. Ecol 60, 708–720 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seif Y et al. Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions of multiple Salmonella strains reveal serovar-specific metabolic traits. Nat. Commun 9, 3771 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.John J, George S, Nori SRC & Nelson-Sathi S Phylogenomic Analysis Reveals the Evolutionary Route of Resistant Genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Genome Biol. Evol 11, 2917–2926 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holt KE et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, E3574–81 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang Z-K, Luo H, Zhang Y, Wang B & Gao F Pan-genomic analysis provides novel insights into the association of E.coli with human host and its minimal genome. Bioinformatics 35, 1987–1991 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Monk JM et al. Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions of multiple Escherichia coli strains highlight strain-specific adaptations to nutritional environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 20338–20343 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first study that focused on strain-level study of E. coli using GEMs.

- 92.Fang X et al. Escherichia coli B2 strains prevalent in inflammatory bowel disease patients have distinct metabolic capabilities that enable colonization of intefstinal mucosa. BMC Syst. Biol 12, 66 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fang X et al. Metagenomics-Based, Strain-Level Analysis of Escherichia coli From a Time-Series of Microbiome Samples From a Crohn’s Disease Patient. Front. Microbiol 9, 2559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bosi E et al. Comparative genome-scale modelling of Staphylococcus aureus strains identifies strain-specific metabolic capabilities linked to pathogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, E3801–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seiler N & Atanassov CL The natural polyamines and the immune system. Prog. Drug Res 43, 87–141 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Norsigian CJ et al. Comparative Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling of Metallo-Beta-Lactamase–Producing Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology vol. 9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Norsigian CJ, Kavvas E, Seif Y, Palsson BO & Monk JM iCN718, an Updated and Improved Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Reconstruction of Acinetobacter baumannii AYE. Front. Genet 9, 121 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fouts DE et al. What Makes a Bacterial Species Pathogenic?:Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Genus Leptospira. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases vol. 10 e0004403 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nogales J et al. High~quality genome~scale metabolic modelling of Pseudomonas putida highlights its broad metabolic capabilities. Environ. Microbiol 22, 255–269 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kavvas ES, Yang L, Monk JM, Heckmann D & Palsson BO A biochemically-interpretable machine learning classifier for microbial GWAS. Nat. Commun 11, 2580 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sánchez BJ et al. Improving the phenotype predictions of a yeast genome-scale metabolic model by incorporating enzymatic constraints. Mol. Syst. Biol 13, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carrera J et al. An integrative, multi-scale, genome-wide model reveals the phenotypic landscape of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol 10, 735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thiele I, Jamshidi N, Fleming RMT & Palsson BØ Genome-Scale Reconstruction of Escherichia coli’s Transcriptional and Translational Machinery: A Knowledge Base, Its Mathematical Formulation, and Its Functional Characterization. PLoS Computational Biology vol. 5 e1000312 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Milo R & Phillips R Cell Biology by the Numbers (Garland Science, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lerman JA et al. In silico method for modelling metabolism and gene product expression at genome scale. Nat. Commun 3, 929 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu JK, O’Brien EJ & Lerman JA Reconstruction and modeling protein translocation and compartmentalization in Escherichia coli at the genome-scale. BMC Syst. Biol (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Heckmann D et al. Machine learning applied to enzyme turnover numbers reveals protein structural correlates and improves metabolic models. Nat. Commun 9, 5252 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lloyd CJ et al. COBRAme: A computational framework for genome-scale models of metabolism and gene expression. PLoS Comput. Biol 14, e1006302 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A framework that streamlines ME model reconstruction and analysis.

- 109.Liu JK et al. Predicting proteome allocation, overflow metabolism, and metal requirements in a model acetogen. PLoS Comput. Biol 15, e1006848 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salvy P & Hatzimanikatis V The ETFL formulation allows multi-omics integration in thermodynamics-compliant metabolism and expression models. Nat. Commun 11, 30 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An implementation of the ME-models called ETFL, for expression and thermodynamics flux models.

- 111.Salvy P & Hatzimanikatis V Emergence of diauxie as an optimal growth strategy under resource allocation constraints in cellular metabolism. bioRxiv 2020.07.15.204420 (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.07.15.204420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Caspi R et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D471–80 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]