Abstract

Arabidopsis thaliana polyamine oxidase 5 gene (AtPAO5) functions as a thermospermine (T-Spm) oxidase. Aerial growth of its knock-out mutant (Atpao5-2) was significantly repressed by low dose(s) of T-Spm but not by other polyamines. To figure out the underlying mechanism, massive analysis of 3′-cDNA ends was performed. Low dose of T-Spm treatment modulates more than two fold expression 1,398 genes in WT compared to 3186 genes in Atpao5-2. Cell wall, lipid and secondary metabolisms were dramatically affected in low dose T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2, in comparison to other pathways such as TCA cycle-, amino acid- metabolisms and photosynthesis. The cell wall pectin metabolism, cell wall proteins and degradation process were highly modulated. Intriguingly Fe-deficiency responsive genes and drought stress-induced genes were also up-regulated, suggesting the importance of thermospermi′ne flux on regulation of gene network. Histological observation showed that the vascular system of the joint part between stem and leaves was structurally dissociated, indicating its involvement in vascular maintenance. Endogenous increase in T-Spm and reduction in H2O2 contents were found in mutant grown in T-Spm containing media. The results indicate that T-Spm homeostasis by a fine tuned balance of its synthesis and catabolism is important for maintaining gene regulation network and the vascular system in plants.

Keywords: Polyamine, Polyamine oxidase, Thermospermine, MACE, Gene expression

Introduction

Polyamines play important roles in growth, development and defence responses to environmental changes in plants. The major polyamines in plants are the diamine putrescine (Put), the triamine spermidine (Spd), and two tetraamines, spermine (Spm) and its isomer thermospermine (T-Spm). Put and Spd are essential for normal plant growth, whereas Spm and T-Spm involvement is not well studied (Tiburcio et al. 2014). However, an Arabidopsis acaulis5 mutant lacking T-Spm synthase activity displays severe defects in stem growth (Hanzawa et al. 2000; Knott et al. 2007; Takahashi 2020). Thus, T-Spm plays important roles in Arabidopsis growth, especially vascular development (Fuell et al. 2010; Takano et al. 2012). Furthermore, an Arabidopsis mutant lacking both Spm and T-Spm synthase activities have been demonstrated to be hypersensitive to drought and high salinity, and this sensitivity is abrogated by exogenously supplied (or pretreatment with) Spm (Yamaguchi et al. 2006, 2007). These results suggest that both Spm and T-Spm play important roles in development and/or defence responses to environmental stresses (Tiburcio et al. 2014).

Polyamine metabolism is governed by a dynamic balance between biosynthesis and catabolism. The latter process has been well studied in animals. Spd/SpmN1-acetyltransferase modifies Spd and Spm. Then, animal PAO catabolizes N1-acetyl Spm and N1-acetyl Spd at the carbon on the exo-side of the N4-nitrogen to produce Spd and Put, respectively (Wang et al. 2001; Cona et al. 2006). Animal cells also contain Spm oxidase (SMO), which catabolizes Spm at the carbon on the exo-side of the N4-nitrogen to produce Spd, 3-aminopropanal and H2O2 without acetyl modification (Vujcic et al. 2002; Cervelli et al. 2003). Both animal PAO and SMO are categorized as back-conversion enzymes.

In plants, thirteen PAOs have been biochemically characterized to date (Bordenave et al. 2019). They differ in polyamine substrate specificity, subcellular localization and mode of reaction (Kusano et al. 2015). Plant PAOs are divided into two groups based on their modes of reaction: those in one group catalyse a terminal catabolic reaction, whereas the other group catalyse a back-conversion reaction (Cona et al. 2006; Kusano et al. 2015; Bordenave et al. 2019). Enzymes of the former group oxidize the carbon on the endo-sides of the N4-nitrogens of Spm and Spd, producing N-(3-aminopropyl)-4-aminobutanal and 4-aminobutanal, respectively, concomitantly generating 1,3-diaminopropane and H2O2. The latter group enzymes oxidize Spm, T-Spm and/or Spd by back conversion, similar to animal PAO (Moschou et al. 2008).

Previously we showed that Arabidopsis thaliana PAO5 (AtPAO5) encodes a protein that functions as a T-Spm oxidase (Kim et al. 2014). The knock-out mutant, Atpao5-2, contained two-fold higher T-Spm compared to that of wild type (WT) Col-0 plant, and aerial growth of the mutant was severely disrupted when the plants grew on low doses (5 or 10 μM) T-Spm-contained Murashige-Skoog (MS) agar media (Kim et al. 2014). T-Spm is also involved in the xylem differentiation through the activation of cytokinin and auxin signalling pathways (Alabdallah et al. 2017) and was shown to have effects on the growth and expression of different polyamine related genes in rice seedlings (Miyamoto et al. 2020). Here we aimed to figure out the underlying mechanism of the above phenomenon. Massive analysis of 3′ cDNA ends (MACE) method revealed that Fe-deficient responsive genes and water-stress responsive genes are markedly induced in T-Spm treated Atpao5-2 plant. Furthermore, in the transition zone from stem to leaves the vascular system is disconnected in low dose T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2. The results indicate that, if the T-Spm content reaches the upper threshold, the vascular system becomes defective not only structurally but also functionally.

Material and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

A. thaliana wild-type (WT) plants [accession Columbia-0 (Col-0)] and the T-DNA insertion line of AtPAO5 (provided by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center, Ohio State University) were used in this work. All seeds were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min, then with a solution of 1% sodium hypochloride and 0.1% Tween-20 for 15 min, followed by extensive washing with sterile distilled water. Sterilized seeds were placed on half-strength Murashige-Skoog (MS)-1.5% agar plates (pH 5.6) containing 1% sucrose. For treatment with T-Spm the agar plates contained 5 μM T-Spm. Growth conditions were 22 °C with a 14 h light/10 h dark photocycle.

Genome-wide gene expression profiling by massive analysis of cDNA ends (MACE)

Total RNA was extracted from leaves using Sepasol-RNA I Super (NacalaiTesque, Kyoto, Japan) and further purified by DNase treatment and NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up XS kit (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany). Quantification and quality control was performed on a Bioanalyzer 2100 instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Massive analysis of 3′-cDNA ends (MACE, Zawada et al. 2014) libraries were prepared and sequenced by GenXPro GmbH (Yakovlev et al. 2014). MACE is based on the methods described by Torres et al. (2008) and Eveland et al. (2010), combining Illumina sequencing and providing high-resolution gene expression analysis (http://www.genxpro.info/products_and_services/Transcriptomics/RNAseq_MACE_SuperSAGE_digital_gene_Expression/). In brief, poly-adenylated mRNA was isolated from 1 μg of the total RNA using Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) and cDNA was produced by first and second strand synthesis using the SuperScript III System (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) and barcoded 5´-end biotinylated poly-T adapters. Subsequently the biotinylated cDNA was random-fragmented to reach an average size of 250 bps. The 3´-ends of the fragmented cDNA were captured with streptavidin beads, while PCR-bias-proof technology “TrueQuant” was used by ligation of TrueQuant adapters to distinguish PCR copies from original copies (GenXPro GmbH). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Analysis of MACE read libraries was performed using a pipeline performing a read quality control using FastQC (James et al. 2011), linker sequences trimming via BLAT (Kent 2002), read-mapping onto the Arabidopsis genome (AtGDB) via SSAHA2 (Ning et al. 2001) and transcripts counting considering that each MACE read comes from one transcript. The number of transcripts per gene is normalized by the library size of mapped reads multiplied by one million. The gene counts of the MACE libraries are deposited on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Transcripts clustering using expressional changes

Eight MACE libraries were used to analyze the up- and down—regulation of genes in a knock-out mutant (Atpao5-2) of AtPAO5 under with or without 5 μM T-Spm treatment. The mean of the two replicates per condition and treatment were calculated. We generated data from four different experemental conditions: wild type control (WTCo), wild type treated with T-Spm (WTTS), Atpao5-2 mutant control (pao5Co) and Atpao5-2 mutant treated with T-Spm (pao5TS) for the clustering. The clustering was done with MeV (Saeed et al. 2003) and expression analyses are further visualized by MapMan (Thimm et al. 2004). Clustering all the annotated Arabidopsis genes concerning their expression level of four different conditions via MeV was done using a k-means clustering creating 100 clusters with Euclidean distance and 100 iterations. Furthermore a hierarchical clustering was also performed using Euclidean distance and average linking distance. Besides, MapMan was used to visualize the expression level of metabolic pathway genes of the TIAR9. The genes are categorized in cell wall, lipids, amino acids, second metabolism, light reactions, starch, sucrose, OPP, TCA, tetrapyrrole, NO3, SO4 and minor CHO.

Differential expression analyses

For analyzing differentially expressed genes in the MACE libraries, we used the DESeq2 libraries of the Bioconductor package (Gentleman et al. 2004) in R (http://www.r-project.org/). R scripts including the DESeq2 library were started with the RStudio computing environment (http://www.rstudio.com/). Two biologically different replicates were used to determine the differentially expressed transcripts for each treatments. Differenes of control and T-Spm treated samples of WT and Atpao5-2 mutant (Pao5_Co/WT_Co and Pao5_TS/WT_TS) were compared. All the genes in these comparisons having a p-value lower than 0.1 were categorized to be significant differentially expressed. Furthermore, we used species specific database AraCyc 11.5 (Chae et al. 2012) to identify the genes involved in the polyamine metabolism pathway. As control we also calculated the expression levels of common marker genes like ubiquitin (UBQ11), actin (ACT2) and glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

RT and quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses

Total RNA was extracted from leaves or roots using Sepasol-RNA I Super (NacalaiTesque, Kyoto, Japan) as described by Sagor et al. (2019). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with ReverTra Ace (Toyobo Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) using oligo-dT primers. RT-PCR analysis was performed as described (Sagor et al. 2012) using the primers listed in Table S1. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using Fast-Start Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX) (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), on a StepOne real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system (Life Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Specific primer sets were designed and are listed in Table S2. The amount of target mRNA was normalized using the housekeeping gene encoding the cap binding protein 20 (CBP20), which was amplified with the primer pair listed in Table S2.

Histology and microscopy

To observe vascular system, 6-day-old seedlings were fixed in a mixture solution of ethanol and acetic acid (6:1 v/v) overnight, incubated in 100% ethanol for 30 min twice, in 70% ethanol for 30 min once, and then cleared with a mixture solution of chloral hydrate, glycerol and water (8:1:2, w/v/v) overnight. Then the seedlings were placed in glass slide and observed under a phase contrast microscope (BX61; Olympus).

Ion measurement

Seedlings were collected, rinsed by deionic water three times and dried at 65 °C for 2 d. Dried plant samples were digested with 100% nitric acid at 130 °C for 90 min, filtered and the ion concentrations were analyzed by ICP spectrophotometer (iCAP 6000 series, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA).

Analysis of PA by high-performance liquid chromatography

PA extraction, benzoylation and analysis by HPLC were performed using the procedure described in Liu et al. 2014. The benzoylated polyamines were analyzed using a programmable Hewlett Packard series 1200 liquid chromatograph. One cycle consisted of a total 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Measurement of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content

The content of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was measured according to Ferdousy et al. 2020. Briefly, 0.1 g leaf tissues were grounded using liquid nitrogen and 1 ml of 0.1% TCA was added as extraction buffer. After centrifugation, the supernatant was taken, mixed with 10 mM phosphate buffer, 1 M potassium iodide and kept in dark for 1 h, after that the absorbance was recorded at 390 nm wavelength in a spectrophotometer. The titer was calculated using extinction coefficient 0.28 µM−1 cm−1.

Results

Low dose of T-Spm severely disrupts the growth aerial part of Atpao5-2 mutant plant

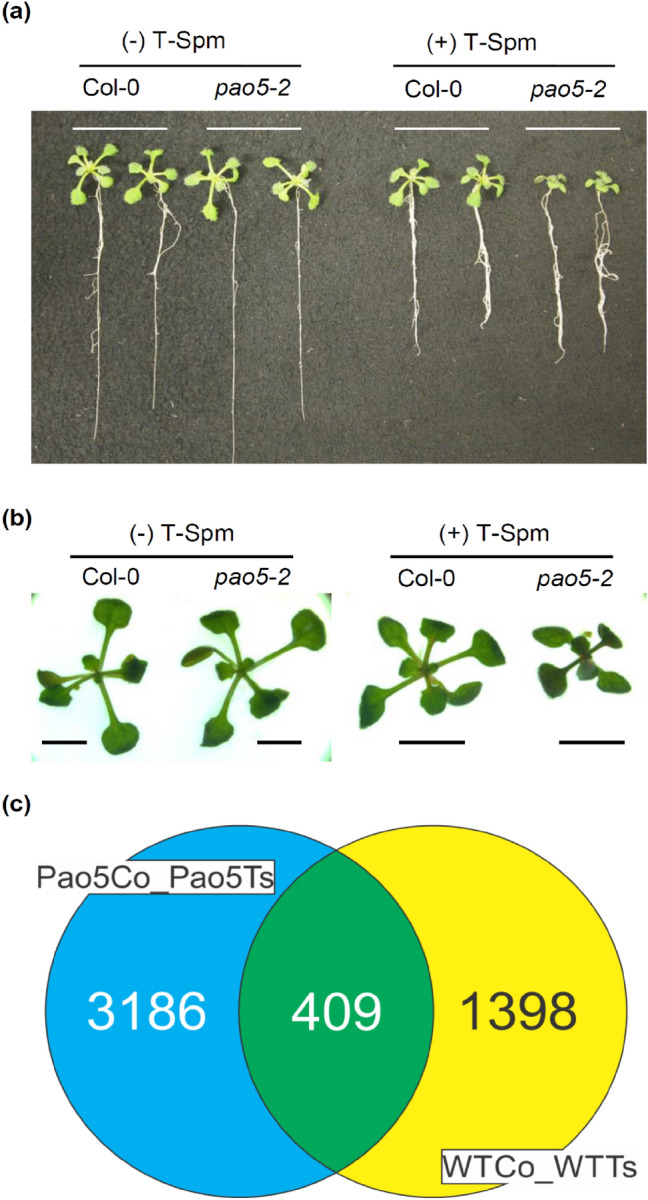

A. thaliana WT (Col-0) and Atpao5-2 mutant were grown vertically on MS agar media or 5 μM T-Spm containing MS agar media for 14 days. Under control condition (MS), WT and Atpao5-2 grew comparably (Fig. 1a, left panel). In presence of 5 μM T-Spm (T-Spm), the root growth was inhibited with similar extent whereas the growth of the aerial part of Atpao5-2 was severely disrupted in comparison to WT plants (Fig. 1a, b). This growth arrest was T-Spm-specific. Other polyamines like Put, Spd and Spm do not have such effects (data not shown). At higher T-Spm concentration (10 μM) a severe arrest in growth was observed (Kim et al. 2014).

Fig. 1.

Growth phenotypes and differentially expressed genes in WT and Atpao5-2 mutant grown in the half MS media with or without 5 μM T-Spm treatments. a Growth of WT (Col-0) and Atpao5-2 mutant under normal- (a, left) and 5 μMT-Spm supplied condition (a, right) at 14 days after placing seeds on the agar media. b Magnified views of the aerial parts of WT and Atpao5-2 grown at normal half MS agar media and 5 μM T-Spm-contained half MS agar media. Bar indicates 1 mm. c Venn diagram displays the twofold differentially expressed genes after 5 μM T-Spm treatment of WT (WTCo_WTTs) and Atpao5-2 mutant (Pao5Co_Pao5Ts) plants. The numbers in each section show the number of twofold differentially expressed genes

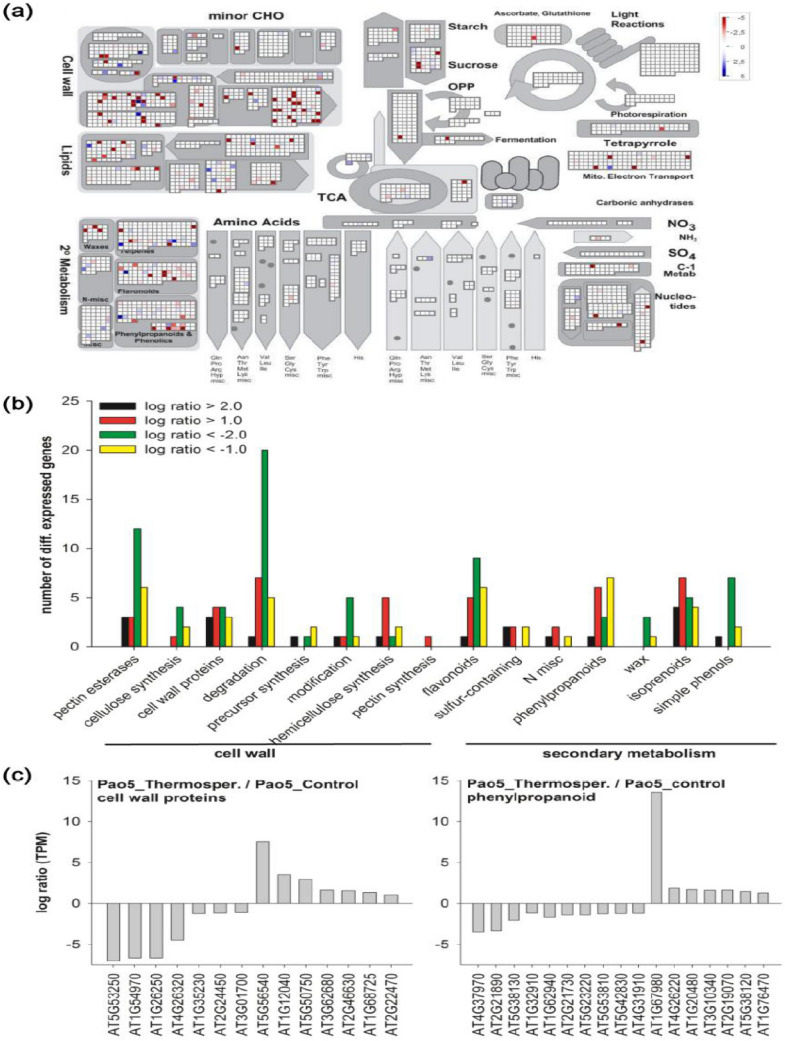

Cell wall, lipid, and secondary metabolism were affected in T-Spm treated Atpao5-2

To uncover the molecular bases of T-Spm effect, gene expression analyses were performed by MACE (Zawada et al. 2014). In low dose (5 μM) T-Spm treated WT (WTTs), 1,398 genes were differentially expressed C twofold compared to untreated WT (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, in Atpao5-2, 3,186 genes were modulated with ≥ twofold difference in 5 μM T-Spm treatment (Fig. 1c). Four hundred nine genes were affected in common by T-Spm in WT and Atpao5-2 (Fig. 1c). Further, to identify the metabolic pathways that are affected by the differential expression of the 3,186 genes, Mapman analysis was performed. Cell wall-, lipid- and secondary- metabolisms were strikingly affected in 5 μM treated Atpao5-2 (Fig. 2a), whereas other pathways such as TCA cycle-, amino acid- metabolisms and photosynthesis were not much affected (Fig. 2a). The cell wall, pectin metabolism, cell wall proteins and degradation processes were highly modulated (Fig. 2b). The genes, encoding arabinogalactan protein (At5g53250, At4g26320, At1g35230, At2g244450, At3g01700), proline-rich protein (At1g54970) and extensin-like family protein (At1g26250), were down-regulated, on the other hand, the genes, encoding arabinogalactan protein (At5g56540, At1g68725, At2g22470), extensin-like family protein (At1g12040), UDP-glucose protein transglucosylase (At5g50750) and proline-rich protein (At3g62680) were upregulated (Fig. 2c). Secondary metabolism, flavonoid-, phenylpropanoid- and isoprenoid- pathways were affected (Fig. 2b). The genes, encoding cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (At4g37970, At2g21890, At2g21730), HXXXD-type acyl transferase (At5g38130, At1g32910, At5g42830, At4g31910), acyl-CoA synthase (At1g62940), nicotinamidase (At5g23220), O-methyltransferase (At5g53810), caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase (At1g67980, At4g26220) and 4-coumarate CoA ligase (At5g38120, At1g20480), were found modulated (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Mapman analysis between Atpao5-2 and Atpao5-2 T-Spm treatments (a), the numbers of the differentially expressed genes in cell wall and secondary metabolism (b) and the major affected genes in cell wall and phenylpropanoid pathway (c)

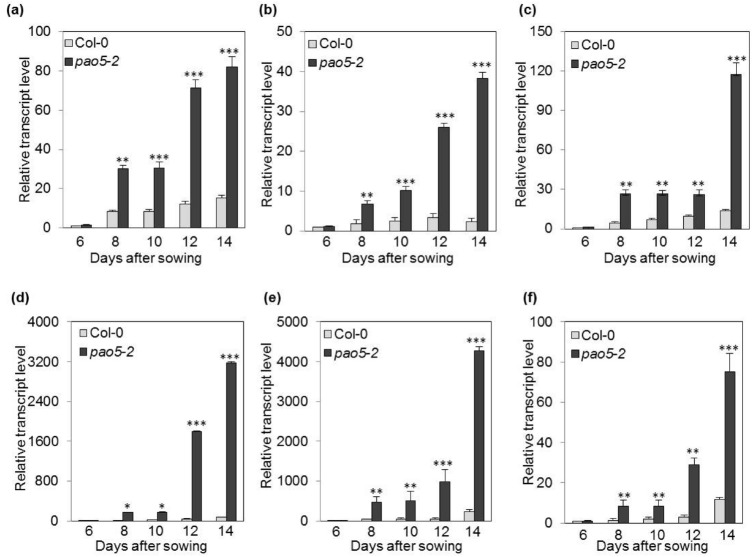

Fe-deficient responsive genes and dehydration responsive genes were upregulated in Atpao5-2

Among the 3,186 genes, the top 20 up- and down-regulated genes in 5 μM T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 mutant were identified (Table 1), and their expression was validated by RT-PCR analysis using the primer pairs listed in Table S1 (Fig. S1). Under control condition, the expression of up-regulated genes was not significantly changed in WT and Atpao5 mutant (Fig. S1). Among the up-regulated genes, #1–#4, #6, #8, #9 and #16–#20 transcripts were specifically accumulated in T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 but not in Col-0 either in control or T-Spm treated condition (Fig S1). Rodriguez-Celma et al. (2013) reported that a subset of seven unknown proteins [At1g47400, At2g14247, At1g13609, At1g47395, At3g56360, At2g30766 and At5g67370] were strongly up-regulated in leaves of the Arabidopsis plant grown in Fe-deficient conditions. Out of them, At2g30766, At1g47400 and At2g14247 correspond to #1, #2 (iron-responsive protein 1, IRP1) and #4 (iron-responsive protein 3, IRP3), respectively. To further confirm the expression of #1, IRP1 (#2) and IRP3 (#4), qRT-PCR was performed using the primer pairs listed in Supplemental table S2. Their expression was clearly upregulated at 8-day- and then in later growth stage after placing the seeds on T-Spm contained MS media (Fig. 3a–c). In addition, the three bHLH transcription factor genes, bHLH38, bHLH100 and bHLH101, responsive to Fe deficiency (Wang et al. 2007) were also upregulated at the same time point (Fig. 3d–f). Inferred from the above data, the Fe, Ca, Na and K contents in T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2, were measured to test for Fe deficiency. Ca, Na and K contents in T-Spm-treated- WT and Atpao5-2 did not differ much (Fig. S2b–d). The Fe content of T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 was lower than that of T-Spm-treated WT but it was higher than that both the controls, WT and Atpao5-2 (Fig. S2a). Furthermore, #6 and #9 encoding late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins were also upregulated in T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2. This suggests that Fe ion and water movement in T-Spm-treated plant was somehow disturbed.

Table 1.

Top 20 up- and down-regulated genes in Atpao5-2 plants treated with 5 μM T-Spm

| AGI code | Fold change | Annotation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated genes | |||

| 1 | AT2G30766 | 7.7904 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 2 | AT1G47400 | 7.7462 | Iron-responsive protein 1 |

| 3 | AT3G48520 | 6.0007 | Cytochrome P450, family 94, subfamily B, polypeptide 3 |

| 4 | AT2G14247 | 5.9857 | Iron-responsive protein 3 |

| 5 | AT5G05220 | 5.8196 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 6 | AT2G21490 | 5.747 | dehydrin LEA |

| 7 | AT5G45630 | 5.7207 | Uncharacterized protein, senescence reg superfamily |

| 8 | AT4G34410 | 5.6818 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF 109 |

| 9 | AT1G52690 | 5.4621 | LEA protein |

| 10 | AT1G56060 | 5.4482 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 11 | AT1G19210 | 5.4371 | AP2 domain-containing DNA binding factor |

| 12 | AT1G63030 | 5.3786 | ERF/AP2 transcription factor DDF2 |

| 13 | AT1G12610 | 5.2885 | dehydration-responsive element-binding protein IF |

| 14 | AT5G62520 | 5.1301 | Inactive poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase SR05 |

| 15 | AT3G01830 | 5.1075 | Putative calcium-binding protein CML40 |

| 16 | AT5G59310 | 5.01 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein type I, (nsLTPl) |

| 17 | AT1G28480 | 4.9518 | Glutaredoxin-GRX480 |

| 18 | AT5G50360 | 4.9279 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 19 | AT1G73510 | 4.9249 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 20 | AT1G09950 | 4.9242 | Response to ABA and salt 1 |

| Downregulated genes | |||

| 1 | AT5G44440 | − 3.2649 | Berberine bridge enzyme-like protein |

| 2 | AT1G29490 | − 3.1555 | SMALL AUXIN UPREGULATED 68 |

| 3 | AT1G64220 | − 2.9932 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM7-2 |

| 4 | AT2G20980 | − 2.7723 | Minichromosome maintenance protein 10 |

| 5 | AT3G53250 | − 2.7493 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein |

| 6 | AT3G51400 | − 2.7195 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 7 | AT1G22690 | − 2.685 | Gibberellin-regulated protein 9 |

| 8 | AT3G48490 | − 2.4305 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 9 | AT5G03545 | − 2.398 | Uncharacterized protein |

| 10 | AT5G61000 | − 2.3606 | Replication protein A 70 kDa DNA-binding subunit D |

| 11 | AT4G34790 | − 2.3598 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein |

| 12 | AT1G24260 | − 2.2972 | MADs box transcription factor SEPALLATA3 |

| 13 | AT5G51720 | − 2.2775 | Iron-binding zinc finger CDGSH type, Fe-S domain-containing protein |

| 14 | AT3G09922 | − 2.2614 | Protein ED BY PHOSPHATE STARVATION 1 |

| 15 | AT5G18030 | − 2.2339 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein |

| 16 | AT4G28720 | − 2.1544 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase YUCCA8 |

| 17 | AT3G16660 | − 2.0976 | Pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein |

| 18 | AT2G29680 | − 2.0116 | Cell division control 6 |

| 19 | AT1G26540 | − 2.0101 | Agenet domain-containing protein |

| 20 | AT4G30860 | − 2.0042 | Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase ASHR3 |

Fig. 3.

Validation of the upregulation of Fe-deficient responsive genes in 5 μM T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 plants through qRT-PCR. a At2g30766, b IRP1, c IRP3, d bHLH38, e bHLH100, f bHLH101. The values indicate means ± SE (n = 5). Asterisk indicates significant difference between WT (Col-0) and Atpao5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

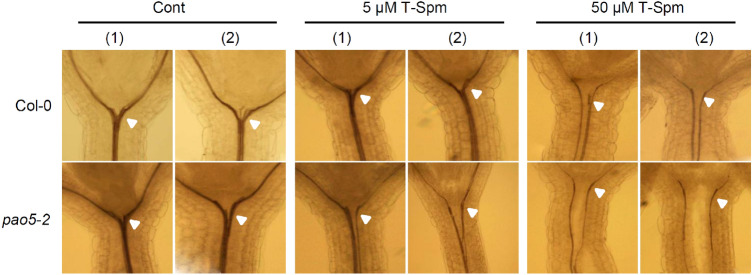

Vascular system of Atpao5-2 was dissociated by low dose T-Spm treatment

Six-day-old WT and Atpao5-2 seedlings grown at normal MS agar media, 5 μM- and 50 μM- T-Spm contained MS agar media were fixed and cleared, then observed under light microscope. As seen in Fig. 4, the vascular system at the joint between stem and leaf in 5 μM T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 was dissociated, whereas the similar portions of 5 μM T-Spm-treated WT seemed to be intact. It should be noted that the structural distortion in vascular system is preceded to the expressional change of the Fe deficient responsive and water stress responsive genes. The higher dose (50 μM) of T-Spm caused the vascular dissociation even in WT whereas the same dose of T-Spm caused the more serious dissociation at the wider region of Atpao5-2 stem (Fig. 4, right).

Fig. 4.

Histological sections of the vascular systems of WT (Col-0) and Atpao5-2 mutant grown at control agar media, 5 μM T-Spm- and 50 μM T-Spm-contained agar media. Six-day-old seedlings grown on MS agar media with or without 5 or 50 μM T-Spm were used in this experiment. Two each views [(1), (2)] of the representative seedlings were displayed. White arrow head indicates the junction of stem and leaves

Endogenous T-Spm and H2O2 contents were changed in Atpao5-2 mutant

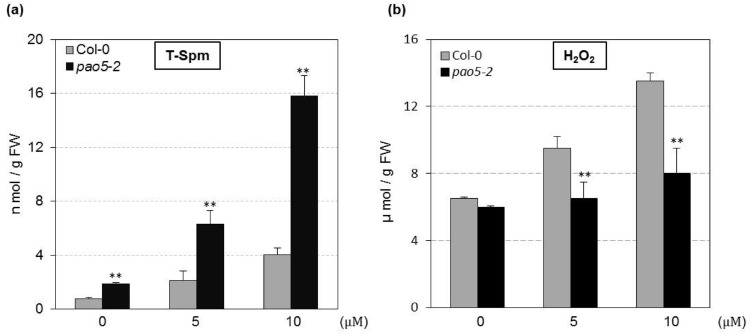

Arabidopsis wild type and Atpao5-2 were grown on MS agar plate containing 0, 5 and 10 μM T-Spm for 14 days and endogenous polyamines and H2O2 contents were measured using aerial parts. The endogenous T-Spm content was 2–4fold higher in Atpao5-2 mutant compared to wild type reaching 6 nmol/g FW and 16 nmol/g FW in 5 μM and 10 μM T-Spm treated mutant plants respectively (Fig. 5a). The concentration of other endogenous polyamines were also changed (Fig S3). The content of H2O2 and signaling molecules for secondary wall deposition were gradually increased in wild type plants grown in T-Spm containing media, but not changed comparably in Atpao5-2 mutant (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Estimation of endogenous thermospermine (T-Spm) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). WT (Col-0) and Atpao5-2 mutant grown on control agar media (0 µM), 5 μM T-Spm- and 10 μM T-Spm-contained agar media for 14 days; Endogenous content of T-spm (a) and H2O2 (b) were measured in aerial parts. The values indicate means ± SE (n = 5). Asterisk indicates significant difference between WT (Col-0) and Atpao5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

Accounting that AtPAO5 catalyzes the inter-conversion of T-Spm to Spd and application of low dose T-Spm to the Atpao5-2 mutant causes distinct damage to the stem vascular system, it can be concluded that a fine tuning of the T-Spm concentration by the activity of T-Spm oxidase may be required to maintain a well-organized vascular system.

Discussion

The Arabidopsis acaulis5 mutant and thick vein mutants, have defects in the T-Spm synthase gene, resulted in dwarf and stem-less phenotypes with thickened veins and increased vascularization (Hanzawa et al. 2000; Clay and Nelson 2005). It was thought that T-Spm has a crucial role for proper vascular development and xylem cell specification (Hanzawa et al. 2000; Clay and Nelson 2005; Takano et al. 2012; Alabadallah et al., 2017; Miyamoto et al. 2020. We previously showed that Arabidopsis AtPAO5 functions as a T-Spm oxidase (Kim et al. 2014). Furthermore, the growth of aerial parts but not of roots of the loss-of-function mutant (Atpao5-2) of the AtPAO5 gene was severely arrested compared to that of WT when the plants were grown on MS media containing low doses of T-Spm (5–10 μM) (Fig. 1a; Kim et al. 2014). Endogenous polyamine contents were changed, especially T-Spm titers increased 2–fourfold in Atpao5-2 plants grown on T-Spm containing media (Fig. 5a). We interpreted that excess T-Spm, due to lack of the back-conversion activity from T-Spm to Spd, again disrupts stem growth. Increased Put and decreased Spd does not have any effects on Atpao5-2 mutant plants (Fig. S3) as exogenously applied Put and Spd could not retard the growth phenotype (Kim et al. 2014). The H2O2 produced through polyamine catabolism acts as signalling molecule for secondary cell wall deposition and xylem development (Tisi et al. 2011). The lower accumulation of H2O2 in Atpao5-2 mutant compared to wild type T-Spm treated plants (Fig. 5b) might also be responsible for the underdevelopment of vascular system. H2O2 content in Atpao5-2 was found also low compared to wild type in response to salinity stress (Ferdousy et al. 2020). Arabidopsis thaliana PAO5 (AtPAO5) protein acts as a T-Spm oxidase/dehydrogenase (Ahou et al. 2014), by contrast Liu et al. 2014 showed AtPAO5 as T-Spm oxidase using loss of function mutants which contained two fold higher T-Spm than wild type plants.

Global gene expression analysis by MACE indicates that cell wall-, lipid- and secondary- metabolisms were remarkably modulated in low dose T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 in relative to untreated Atpao5-2 (Fig. 2). The modulation of the expression of the components of cell wall degradation, pectin metabolism and cell wall proteins such as arabinogalactan proteins (Ellis et al. 2010) may explain why low dose T-Spm negatively affects Atpao5-2 stem growth (Fig. 2). More intriguingly, some, such as #1, #2 and #4, of top 20 upregulated genes in low dose T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 are known to be Fe-deficiency responsive genes (Table 1, Fig. 3a–c). In addition the expression of 3 bHLH-type transcription factor genes which are also involved in Fe-deficient response (Wang et al. 2007; Andriankaja et al. 2014) was upregulated in 8-days of treatment with low dose T-Spm (Fig. 3d–f). The results obtained from MACE and gene expression analysis indicate that low dose T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 plants suffered with Fe deficiency while the Fe content in that plant was sufficient (Fig. S2). The lower content of Fe in T-Spm-treated Atpao5-2 compare to T-Spm-treated WT is may due to some vascular obstruction that caused the induction of Fe deficiency responsive gene in mutant plants. Transcriptional profiling also reveals the induction of different genes involved in Fe deficiency (Thomas et al. 2010). Expression of drought-responsive LEA protein genes was also upregulated (Table 1, Fig S1). LEA genes were found to be involved in drought tolerance and vascular maintenance in cotton (Magwanga et al. 2018). Moreover, histological observation shows that in 6-day-old Atpao5-2 the vascular system at the joint of stem and leaf is apparently dissociated when the plant was treated with low dose of T-Spm (Fig. 4). Collectively, application of low dose of T-Spm to the Atpao5-2 mutant plant but not to WT induces an impairment of the vascular system structurally and functionally. Not only T-Spm synthesis but also its catabolism, through AtPAO5 in A. thaliana, is important for maintaining a vascular system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Simit Patel is acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT) to TK (26·04081, 15K14705) and Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System (BAURES) to GHMS (2017/262/BAU).

Authors’ contribution

GHMS, SS, KDW, Performing lab experiment, collection and analysis of data. MN synthesized uncommon chemicals, GHMS, TK, TB: Design, formulation, supervision of experiment and writing of manuscript.

Declaration

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

G.H.M. Sagor and Stefan Simm these authors contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-021-00967-7.

References

- Ahou A, Martignago D, Alabdallah O, Tavazza R, Stano P, Macone A, et al. A plant spermine oxidase/dehydrogenase regulated by the proteasome and polyamines. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:1585–1603. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alabdallah O, Ahou A, Mancuso N, Pompili V, Macone A, Pashkoulov D, Stano P, Cona A, Angelini R, Tavladoraki P. The Arabidopsis polyamine oxidase/dehydrogenase 5 interferes with cytokinin and auxin signalling pathways to control xylem differentiation. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(5):997–1012. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriankaja ME, Danisman S, Mignolet-Spruyt LF, Claeys H, Kochanke I, Vermeersch M, et al. Transcriptional coordination between leaf cell differentiation and chloroplast development established by TCP20 and the subgroup Ib bHLH transcription factors. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85:233–245. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenave CD, Mendoza CG, Bremont JFJ, Garriz A, Rodriguez A. Defining novel plant polyamine oxidase subfamilies through molecular modelling and sequence analysis. BMC Evolt Biol. 2019;19:28. doi: 10.1186/s12862-019-1361-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervelli M, Polticelli F, Federico R, Mariottini P. Heterologous expression and characterization of mouse spermine oxidase. J BiolChem. 2003;278:5271–5276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae L, Lee I, Shin J, Rhee SY. Towards understanding how molecular networks evolve in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay NK, Nelson T. Arabidopsis thickvein mutation affects vein thickness and organ vascularization, and resides in a provascular cell-specific spermine synthase involved in vein definition and in polar auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:767–777. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cona A, Rea G, Angelini R, et al. Functions of amine oxidases in plant development and defence. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis EC, Goldewijk KK, Siebert S, Lightman D, Ramankutty N. Anthropogenic transformation of the biomes, 1700 to 2000. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;19(5):589–606. [Google Scholar]

- Eveland AL, Satoh Nagasawa N, Goldshmidt A, Meyer S, Beatty M, Sakai H, Ware D, Jackson D. Digital gene expression signatures for maize development. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1024–1039. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.159673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdousy NE, Arif MTU, Sagor GHM. Polyamine oxidase (PAO5) mediated antioxidant response to promote salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J of Bangladesh Agric Univ. 2020;18(2):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Fuell C, Elliot KA, Hanfrey CC, Franceschetti M, Michael AJ. Polyamine biosynthetic diversity in plants and algae. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Takahashi T, Michael AJ, Burtin D, Long D, Pineiro M, Coupland G, Komeda Y. ACAULIS5, an Arabidopsis gene required for stem elongation, encodes a spermine synthase. EMBO J. 2000;19:4248–4256. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Andrews S, Walker S, de Sousa PR, Ray A, Russell NA, Bellamy TC. High-throughput analysis of calcium signalling kinetics in astrocytes stimulated with different neurotransmitters. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT-the blast like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DW, Watanabe K, Murayama C, Izawa S, Niitsu M, Michael AJ, Berberich T, Kusano T. Polyamine oxidase5 regulates Arabidopsis thaliana growth through a thermospermine oxidase activity. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1575–1590. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.242610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott JM, Romer P, Sumper M. Putative spermine synthases from Thalassiosira pseudonana and Arabidopsis thaliana synthesize thermospermine rather than spermine. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3081–3086. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano T, Kim DW, Liu T, Berberich T. Polyamine catabolism in plants. In: Kusano T, Suzuki H, editors. Polyamine: a universal molecular nexus for growth, survival and specialised metabolism. NewYork: Springer; 2015. pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Dobashi H, Kim DW, Sagor GHM, Niitsu M, Berberich T, Kusano T. Arabidopsis mutant plants with diverse defects in polyamine metabolism show unequal sensitivity to exogenous cadaverine probably based on their spermine content. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2014;20(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s12298-014-0227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwanga RO, Lu P, Kirungu JN, et al. Characterization of the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins family and their role in drought stress tolerance in upland cotton. BMC Genet. 2018;19:6. doi: 10.1186/s12863-017-0596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto M, Shimao S, Tong W, Motose H, Takahashi T. Effect of thermospemine on the growth and expression of polyamine related genes in rice seedlings. Plants. 2020;8:269. doi: 10.3390/plants8080269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschou PN, Sanmartin M, Andriopoulou AH, Rojo E, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Roubelakis-Angelakis KA. Bridging the gap between plant and mammalian polyamine catabolism: a novel peroxisomal polyamine oxidase responsible for a full back- conversion pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:1845–1857. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, Cox AJ, Mullikin JC. SSAHA: a fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 2001;11(10):1725–1729. doi: 10.1101/gr.194201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Celma J, Lin WD, Fu GM, Abadia J, López-Millán AF, Schmidt W. Mutually exclusive alterations in secondary metabolism are critical for the uptake of insoluble iron compounds by Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1473–1485. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagor GHM, Takahashi H, Niitsu M, Takahashi Y, Berberich T, Kusano T. Exogenous thermospermine has an activity to induce a subset of the defense genes and restrict cucumber mosaic virus multiplication in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:1227–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagor GHM, Kusano T, Berberich T. A polyamine oxidase from Selaginella lepidophylla (SelPAO5) can replace AtPAO5 in Arabidopsis through converting thermospermine to norspermidine instead to spermidine. Plants. 2019;8(4):99. doi: 10.3390/plants8040099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. Plant polyamines. Plants. 2020;9:511. doi: 10.3390/plants9040511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano A, Kakehi JI, Takahashi T. Thermospermine is not a minor polyamine in the plant kingdom. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:606–616. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O, Blaesing OE, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Krueger P, Selbig J, Mueller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M. Mapman: a user-driven tool to display genomics datasets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiburcio AF, Altabella T, Bitrian M, Alcazar R. The roles of polyamines during the lifespan of plants: from development to stress. Planta. 2014;240:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisi A, Federico R, Moreno S, Lucretti S, Moschou PN, Roubelakis-Angelakis KA, Angelini R, Cona A. Perturbation of polyamine catabolism can strongly affect root development and xylem differentiation. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:200–215. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.173153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres TT, Metta M, Ottenwälder B, Schlötterer C. Gene expression profiling by massively parallel sequencing. Genome Res. 2008;18(1):172–177. doi: 10.1101/gr.6984908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JW, Yang Wen-Dar Lin, Wolfgang S (2010) Transcriptional profiling of the Arabidopsis iron deficiency response reveals conserved transition metal homeostasis networks. Plant Physiol 152(4):2130–2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vujcic S, Diegelman P, Bacchi CJ, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel flavin-containing spermine oxidase of mammalian cell origin. Biochem J. 2002;367:665–675. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Devereux W, Woster PM, et al. Cloning and characterization of a human polyamine oxidase that is inducible by polyamine analogue exposure. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5370–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Klatte M, Jakoby M, Baumlein H, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. Iron deficiency mediated stress regulation of four subgroup IRBHLH gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;226(4):897–908. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev I, Lee Y, Rotter B, Olsen J, Skrøppa T, Johnsen Ø, Fossdal C. Temperature-dependent differential transcriptomes during formation of an epigenetic memory in Norway spruce embryogenesis. Tree Genet Genomes. 2014;10:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Takahashi Y, Berberich T, Imai A, Miyazaki A, Takahashi T, Michael A, Kusano T. The polyamine spermine protects against high salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6783–6788. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Takahashi Y, Berberich T, Imai A, Takahashi T, Michael A, Kusano T. A protective role for the polyamine spermine against drought stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, Müller S, Rotter B, Winter P, Fliser D, Heine GH. Massive analysis of cDNA Ends (MACE) and miRNA expression profiling identifies proatherogenic pathways in chronic kidney disease. Epigenetics. 2014;9:161–172. doi: 10.4161/epi.26931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.