Abstract

The translocation PICALM/AF10 is described in multilineage diseases. We report a patient with PICALM/AF10 T/myeloid mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia who achieved durable complete remission after AML‐like treatment suggesting a myeloid origin.

Keywords: mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia, PICALM‐AF10, translocation (1011)(p13q14)

The translocation PICALM/AF10 is described in multilineage diseases. We report a patient with PICALM/AF10 T/myeloid mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia who achieved durable complete remission after AML‐like treatment suggesting a myeloid origin.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mixed‐phenotype leukemia (MPAL) is a rare and high‐risk subtype of leukemia accounting for less than 1% of all leukemias. No consensus exists regarding appropriate treatment. We report a patient with PICALM/AF10 T/myeloid MPAL who reached durable complete molecular remission after acute myeloid leukemia (AML)‐like treatment.

Mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia is a heterogeneous group of leukemias that is extremely rare, accounting for less than 1% of all acute leukemias. 1 Several hematopoiesis patterns have been proposed to explain this mixed phenotype, but the hematopoiesis is more complex than linear models. We report the case of a young man who developed T/myeloid mixed‐phenotype leukemia with extranodal damage and translocation (10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10. The translocation (10;11)(p13; q14) PICALM/AF10 is described in multilineage blood disease, but the physiopathology of PICALM/AF10‐mediated leukemia remains unresolved. PICALM (phosphatidylinositol‐binding clathrin assembly protein, or CALM) is a ubiquitously expressed protein involved in clathrin‐mediated endocytosis and iron homeostasis. 2 AF10 is a transcriptional factor and one of the fusion partners of MLL. The patient achieved complete and durable remission with an AML regimen (3 + 7), followed by HLA‐matched unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Because of limited available data, no gold standard of care exists. An acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)‐like regimen followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation is currently advised 3 ; however, the overall survival of MPAL is poorer than that of ALL (B or T) or AML.

2. MEDICAL HISTORY

A 33‐year‐old man without a relevant medical history sought medical advice because of the rapid appearance of unilateral palpebral ptosis in February 2019. He described night sweats contrasting with overall good physical condition. No tumor syndrome was found other than tumefaction of the medial canthus of the left eye.

Blood tests showed isolated hyper leukocytosis (at 17G/L), with 80% of blast cells, no cytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). Bone marrow aspiration revealed acute myeloblastic leukemia without maturation, including most cells expressing CD34 (98.5%), CD38 (90.5%), and myeloid (CD33 and CD117 and intracytoplasmic myeloperoxidase) and lymphoid (CD7 and CD3) differentiation antigens. The medullary karyotype was complex and displayed the unbalanced translocation (10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10, confirmed by FISH (Figure 1) and multiplexed targeted sequencing of recurrent fusion genes.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Karyotype of our patient showing translocation (10;11)(p13;q14). (B) FISH with MLL break‐apart probes. An 87‐kb probe, labeled in red, covering a region telomeric to the MLL (KMT2A) gene including the marker D11S3207 and a green probe covering a 170‐kb region centromeric to the MLL gene spanning the CD3G and UBE4A genes. The red and green probes are both translocated on 10p, indicating that MLL is not rearranged

This translocation did not remove the MLL gene. The breakpoint region between PICALM and AF10 is represented in Figure 2. No anomaly was detected using next‐generation sequencing of a restricted panel of frequently mutated genes in myeloid malignancies and, more specifically, epigenetic regulatory genes (DNMT3A, EZH2, IDH1, IDH2). Histology analysis following canthus tumefaction biopsy found undifferentiated blast cells expressing CD34, CD45, TdT, Bcl2, CD99, and C117 antigens (Figure 3). Consistent with detecting the clonal rearrangement of the T‐cell receptor (TCR) gene, the diagnosis of early T‐cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia or granulocytic sarcoma was suspected. Brain MRI showed a unilateral and well‐limited mass derived from the left lacrimal gland, (Figure 4) measuring 31 × 17 mm. FDG positron emission tomography (PET) revealed over and under diaphragmatic multiple adenopathy and numerous tissue involvements (Figure 5).

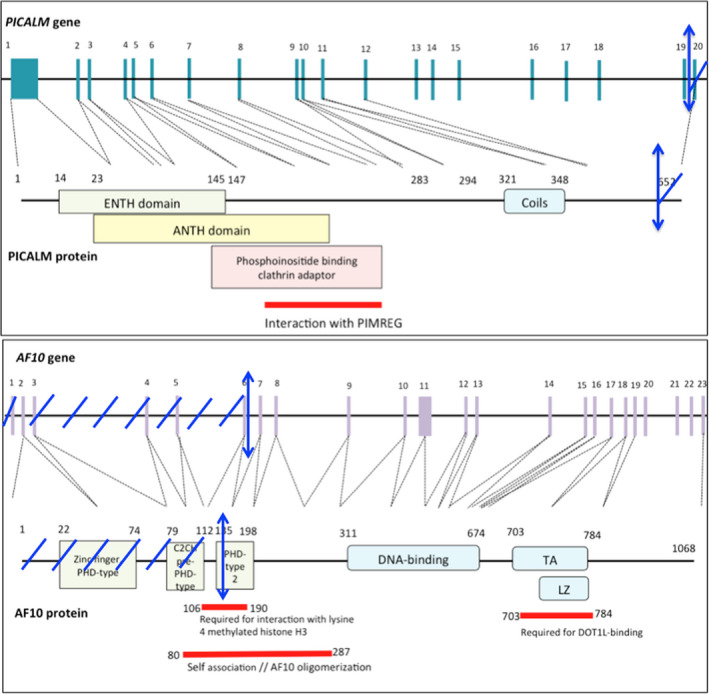

FIGURE 2.

Representation of the PICALM gene with exons corresponding to PICALM functional domains. ENTH domain: epsin N‐terminal homology domain. ANTH domain: AP180 N‐terminal homology domain Representation of the AF10 gene with exons corresponding to AF10 functional domains. The blue arrows represent translocation sites. PHD: plant homeodomain. TA: transactivation domain. LZ: octapeptide motif leucine‐zipper. Reprinted from Uniprot.com and Ensembl.com.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Biopsy of the left lacrimal gland. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×40: Leukemic cells show no morphological features of myeloid or lymphoid differentiation and have several eccentrically placed nucleoli. (B) Lymph node H&E × 10 and (C) lymph node H&E × 40 biopsies show the same morphological aspect as in A. (D) Lymph node: immunohistochemical staining shows strong CD34 expression

FIGURE 4.

Brain MRI. (A) The left lacrimal gland shows hyperintensity on T1‐weighted coronal imaging. (B) The left lacrimal gland shows isointensity on T2‐weighted coronal imaging. (C) The left lacrimal gland shows high restriction on diffusion‐weighted and diffusion‐calculated (ADC) imaging

FIGURE 5.

18F‐Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) at baseline (A) and after induction chemotherapy (B) with a complete response

Because of diagnostic difficulties and uncommon clinical presentation, a second biopsy was performed. The histology of a lymph node concluded T/myeloid mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia (T/M MPAL) with extranodal damage because of the weak positivity of CD4 and high‐intensity clonal rearrangement of the T‐cell receptor gene. The karyotype of this lymph node was the same as that of the bone marrow.

An AML‐like chemotherapy regimen (3 + 7 with cytarabine and daunorubicin) with prophylactic intrathecal injections was started because of MPO positivity and myeloid aspect at cytology. The patient achieved complete molecular remission with negative minimal residual disease using PICALM/AF10 monitoring by dedicated allele‐specific quantitative PCR of bone marrow specimens (Figure 6) and a PET complete metabolic response at D30. The treatment was then completed with one cycle of consolidation chemotherapy comprising high‐dose cytarabine (3 g/m2 D1‐D6) and matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, with myeloablative conditioning (busulfan 3,2 mg/kg/d D‐7 to D‐4 and cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg/d D‐3 to D‐2). The patient is still in complete molecular remission, with a follow‐up of 1 year after transplant.

FIGURE 6.

Dynamic detection of the PICALM‐AF10 transcript by dedicated allele‐specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the bone marrow and blood of the patient

3. DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) is relatively difficult to establish. The WHO 2016 classification 4 defines acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage as leukemia showing no clear differentiation along a single lineage. This group includes acute undifferentiated leukemia and MPAL (or biphenotypic leukemia). MPAL is a rare and high‐risk subtype of leukemia, accounting for less than 1% of all leukemias. 1 The diagnosis requires expression of both lymphoid and myeloid differentiation antigens in the same leukemic cell by flow cytometry. 1 The long‐term survival of MPAL is 47%–75% and 20%–40% for children and adults, respectively.

The genetic basis of mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia remains unclarified, except for two distinct subsets: MPAL with t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) BCR‐ABL1 and MPAL with t(v;11q23) MLL‐rearranged (also known as KMT2A). 4 In our case, MLL was not rearranged. Kern et al 5 analyzed the specimens of 18 MPAL cases (T/M and B/M) by next‐generation sequencing. Most of the genetic mutations identified affected predominantly epigenetic genes (DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1/2, ASLX1) or transcription factors (TP53, RUNX1, ETV6). DNMT3A was the most frequently mutated gene (55,6%; 8/16 MPAL cases), which encodes a DNA methyltransferase. It is mutated early in AML development and considered a founder mutation 6 associated with anthracycline resistance. In a pediatric population, Alexander et al 7 demonstrated by exome, transcriptome, or whole‐exome sequencing that 100% of T/M MPAL presented alterations in genes encoding transcriptional regulators and 88% presented alterations in signaling pathways. They found similar genetic profiles between T/M MPAL and early T‐cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP‐ALL), 7 particularly mutations in RAS and the Jak/STAT pathway.

The translocation (10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10 was first identified by Berger in 1989 in T‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The identification of the same translocation in the U937 cell line originated from a diffuse histiocytic lymphoma 8 enabled Dreyling et al to determine the implicated genes: AF10 at 10p13 and a new gene they named CALM (clathrin assembly lymphoid and myeloid leukemia) at 11q14. 9 Several breakpoints exist: three on the CALM gene and four on the AF10 gene. 10 Located at 11q14, the CALM gene has 24 transcripts by alternative splicing. It encodes 11 potential isoforms of a 652‐amino acid ubiquitous protein called PICALM (phosphatidylinositol‐binding clathrin assembly protein, or CALM). It is a clathrin adaptor protein that binds to the lipids in the plasma membrane and clathrin 11 and plays an important role in clathrin‐mediated endocytosis. The AF10 gene (MLLT10) at 10p13 encodes a putative transcription factor that binds DNA through an AT hook motif 12 and contains a nuclear localization signal. The translocation leads to the fusion of the protein PICALM with AF10 (MLLT10).

Several isoforms of PICALM/AF10 have been detected, and all were associated with leukemogenesis. 10 , 13 Indeed, the translocation has been reported in hematologic diseases of distinct and various lineages, such as T‐ or B‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T‐ALL or B‐ALL), 14 acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML), 15 , 16 , 17 MPAL 10 , 18 , 19 and lymphomas. 9 In Kumon et al’s study, 10 three of five patients with t(10;11) leukemia were young individuals, with a frequent mediastinal mass but no initial central nervous system involvement. Four of them did not respond to treatment (the treatment details were not reported). Interestingly, the immunophenotypes showed coexpression of T‐cell and myeloid antigens in 80% of the cases. 13

The detection of PICALM/AF10 in multilineage hemopathologies favors stem cell or precursor damage. The transduction of mutant CALM‐AF10 cDNA in C57BL/6 mice bone marrow cells led to increased expression of lineage‐uncommitted progenitors in vitro. 20 These cells did not express myeloid‐specific or lymphoid‐specific markers and displayed high levels of c‐kit. Moreover, the translocation was often described as a simple karyotype, suggesting a driving role in the oncogenic process. 9

At the molecular level, PICALM/AF10 induces the overexpression of HOXA cluster genes (particularly Hoxa5) through aberrant methylation of Lys79 of Histone 3 via DOT1L recruitment. 20 Hoxa5 overexpression is critical but not essential for CALM‐AF10‐mediated leukemogenesis. 21 In the Caudell et al study, 21 CALM‐AF10 transgenic mice showed Hoxa5 overexpression, although they did not develop acute leukemia. The penetrance was incomplete, suggesting the need for additional events to trigger leukemic transformation. Other studies demonstrated the upregulation of BMI1 in MPAL with t(10;11). 9 , 22 Bmi1 is a member of the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) family implicated in epigenetic control. This protein is constantly overexpressed in PICALM/AF10 leukemia. The genetic BMI1 depletion prevents and stops the CALM‐AF10‐mediated transformation of hematopoietic stem cells. 23

Despite these molecular characterizations, no consensus exists regarding appropriate treatment for patients with T/M MPAL. The dilemma persists between the choice of AML and ALL‐directed regimens, 7 , 24 although ALL therapy in the first line is currently often proposed. 3 The current hematopoiesis template does not explain the original cell of MPAL. The hypothesis of a myeloid template for hematopoiesis has been proposed in 2008 and 2009. 25 , 26 It postulates that one hematopoietic stem cell initially differentiates into erythroblastic/myeloid precursors and lymphoid/myeloid precursors. However, several authors 27 have demonstrated that the earliest thymic progenitors (ETP) have lymphoid and myeloid potential, arguing in favor of the persistence of transcriptional promiscuity even after lineage commitment. In our report, the AML‐like regimen induced complete remission of T/M MPAL with t(10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10, supporting the case for a myeloid template and the hypothesis of a multipotent precursor.

4. CONCLUSION

MPAL is a very heterogeneous group, comprising T/M, B/T MPAL and subtypes within each group. The T/M MPAL physiopathology remains unclear, and further research is ongoing to unravel new effective treatments. Several therapeutic targets have been disclosed, such as H3K79 methylation alterations, BMI1, and HOXA. Several hypotheses may be required to lead to an apparent identical result. T/M MPAL could originate from a multipotent precursor in some cases or ETP with myeloid potential in other cases. The detection of PICALM/AF10 in multilineage hematological malignancies favors precursor damage. Our report supports the myeloid template and hypothesis of a multipotent precursor for T/M MPAL with t(10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

DK and VC: wrote the manuscript. FJ: reviewed the manuscript. All authors were involved in the care of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Patient's written informed consent to publication was obtained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Published with written consent of the patient.

Krzisch D, Zduniak A, Veresezan L, et al. Successful treatment of t/myeloid mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia with the translocation (10;11)(p13;q14) PICALM/AF10 with 3 + 7 myeloid standard of treatment: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:1507–1513. 10.1002/ccr3.3815

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, VC. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of the patient.

REFERENCES

- 1. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375‐2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ishikawa Y, Maeda M, Pasham M, et al. Role of the clathrin adaptor PICALM in normal hematopoiesis and polycythemia vera pathophysiology. Haematologica. 2015;100:439‐451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolach O, Stone RM. How I treat mixed‐phenotype acute leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:2477‐2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391‐2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kern W, Grossmann V, Roller A, et al. Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia, T/Myeloid, NOS (MPAL‐TM) Has a High DNMT3A Mutation Frequency and Carries Further Genetic Features of Both AML and T‐ALL: Results of a Comprehensive Next‐Generation Sequencing Study Analyzing 32 Genes. Blood. 2012;120:403. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murphy T, Yee KWL. Cytarabine and daunorubicin for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:1765‐1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alexander TB, Gu Z, Iacobucci I, et al. The genetic basis and cell of origin of mixed phenotype acute leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562:373‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris P, Ralph P. Human Leukemic Models of Myelomonocytic Development: A Review of the HL‐60 and U937 Cell Lines. J Leukocyte Biol. 1985;37:407‐422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dreyling MH, Martinez‐Climent JA, Zheng M, et al. The t(1O;11)(p13;q14). in the U937 cell line results in the fusion of the AFJO gene and CALM, encoding a new member of the AP‐3 clathrin assembly protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:4804‐4809. 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumon K, Kobayashi H, Maseki N, et al. Mixed‐lineage leukemia with t(10;11)(p13;q21): An analysis ofAF10‐CALM andCALM‐AF10 fusion mRNAs and clinical features. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:33‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaksonen M, Roux A. Mechanisms of clathrin‐mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:313‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stoddart A, Tennant TR, Fernald AA, et al. The clathrin‐binding domain of CALM‐AF10 alters the phenotype of myeloid neoplasms in mice. Oncogene. 2012;31:494‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Narita M, Shimizu K, Hayashi Y, et al. Consistent detection of CALM‐AF10 chimaeric transcripts in haematological malignancies with t(10;11)(p13;q14) and identification of novel transcripts. Br Journal of Haematology. 1999;105:928‐937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kobayashi H, Hosoda F, Maseki N, et al. Hematologic malignancies with the t(10;11) (p13;q21) have the same molecular event and a variety of morphologic or immunologic phenotypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;20:253‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Genomic and Epigenomic Landscapes of Adult De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059‐2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chaplin T, Ayton P, Bernard OA et al. A Novel Class of Zinc Finger/Leucine Zipper Genes Identified From the Molecular Cloning of the t(10; 11) Translocation in Acute Leukemia. 1995;85:1435‐1441 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abdelhaleem M, Beimnet K, Kirby‐Allen M, et al. High incidence of CALM‐AF10 fusion and the identification of a novel fusion transcript in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia in children without Down’s syndrome. Leukemia. 2007;21:352‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaneko Y, Maseki N, Takasaki N, et al. Clinical and hematologic characteristics in acute leukemia with 11q23 translocations. Blood. 1986;67:484‐491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Savage NM, Kota V, Manaloor EJ, et al. Acute leukemia with PICALM–MLLT10 fusion gene: diagnostic and treatment struggle. Cancer Genet Cytogenetics. 2010;202:129‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okada Y, Jiang QI, Lemieux M, Jeannotte L, Su L, Zhang YI. Leukaemic transformation by CALM–AF10 involves upregulation of Hoxa5 by hDOT1L. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:1017‐1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caudell D, Zhang Z, Chung YJ, Aplan PD. Expression of a CALM‐AF10 Fusion Gene Leads to Hoxa Cluster Overexpression and Acute Leukemia in Transgenic Mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8022‐8031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mulaw MA, Krause AJ, Deshpande AJ, et al. CALM/AF10‐positive leukemias show upregulation of genes involved in chromatin assembly and DNA repair processes and of genes adjacent to the breakpoint at 10p12. Leukemia. 2012;26:1012‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barbosa K, Deshpande A, Chen B‐R, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia driven by the CALM‐AF10 fusion gene is dependent on BMI1. Exp Hematol. 2019;74:42‐51.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borel C, Dastugue N, Cances‐Lauwers V, et al. PICALM–MLLT10 acute myeloid leukemia: A French cohort of 18 patients. Leukemia Res. 2012;36:1365‐1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477‐5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawamoto H, Katsura Y. A new paradigm for hematopoietic cell lineages: revision of the classical concept of the myeloid–lymphoid dichotomy. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:193‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bell JJ, Bhandoola A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature. 2008;452:764‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, VC. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of the patient.