Abstract

Background

“Unmet healthcare needs” refers to the situation in which patients or citizens cannot fulfill their medical needs, likely due to socioeconomic reasons. The purpose of this study was to analyze factors related to unmet healthcare needs among South Korean adults.

Methods

We used a retrospective cross-sectional study design. This nationwide-based study included the data of 26,598 participants aged 19 years and older, which were obtained from the 2013–2017 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Using multiple logistic regression models, we analyzed the associations between factors that influence unmet healthcare needs and participants’ subgroups.

Results

Despite South Korea’s universal health insurance system, in 2017, 9.5% of South Koreans experienced unmet healthcare needs. In both the male and female groups, younger people (age 19–39) had a higher odds ratio (OR) of experiencing unmet healthcare needs compared to older people (reference: age ≥ 60) (men: OR 1.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.35–2.48; women: OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.12–1.81). In particular, unlike men, women’s unmet healthcare needs increased as their incomes decreased (1 quartile OR 1.55, 2 quartiles OR 1.29, 3 quartiles OR 1.26). Men and women showed a tendency to have more unmet healthcare needs with less exercise, worse subjective health state, worse pain, and a higher degree of depression.

Conclusions

The contributing factors of unmet healthcare needs included having a low socioeconomic status, high stress, severe pain, and severe depression. Considering our findings, we suggest improving healthcare access for those with low socioeconomic status.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12955-021-01737-5.

Keywords: Unmet healthcare needs, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Anderson’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, Socioeconomic status

Background

Developing and updating policies related to healthcare access are important objectives for improving healthcare equity in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Though healthcare systems vary in access to services, public health information can help improve the equity of health policies and affect decision-making [1–3]. According to the 2000 World Health Report, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4], a healthcare system is a means of improving health that ensures access to care based on needs, not on ability to pay. In order to examine this, it is important to consider “unmet healthcare needs,” which are indicators used globally to assess healthcare accessibility [5, 6].

The definition of an “unmet need” varies among researchers [7]. However, according to the European parliament, an “unmet healthcare need” is a situation in which no satisfactory method of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment exist [8]. Between 2016 and 2017, the rates of unmet healthcare needs across 27 European countries declined from 2.6% to 1% [9]. Multiple organizations, such as the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), the Community Health Survey (CHS), the Korea Health Panel Survey, and the Korean Welfare Panel Study, have performed secondary data analyses of “unmet healthcare needs” to determine the healthcare status in South Korea. This refers to a situation in which patients or citizens cannot fulfill their medical needs, most likely due to socioeconomic reasons. Notably, KNHANES reported that the rate of unmet healthcare needs in South Korea is steadily declining, falling from 22% in 2007 to 8.8% in 2017 [10].

Most previous studies of unmet healthcare needs are limited in that their data only includes information from one year [11–13] or only targets certain groups of participants (e.g., certain age groups [14–16], women [17], low-income individuals [13, 18, 19], or people with disabilities [20]). However, to integrate different perspectives and opinions of unmet needs, it is crucial to identify and understand the determinants of such needs [21]. According to Chen and Hou [22], there are three main causes of unmet healthcare needs: (a) availability, which is influenced by factors such as long wait times and shortages of services; (b) accessibility, which includes financial and transportation barriers; and (c) acceptability, which relates to patients who are too busy to seek care or who ignore their health problems). Previous studies [11–19] have indicated that most of the reasons for unmet healthcare needs were economic-related; however, a recent study [10] shows that other reasons surpassed the economic reasons.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the socioeconomic factors related to unmet healthcare needs to recommend effective policies that can address this overall issue of healthcare needs. Thus, we applied a multi-dimensional approach (considering how associated factors affect unmet healthcare needs and stratifying the sex and age) to examine the effects of unmet healthcare needs among adults aged 19 years and older.

Methods

Data source

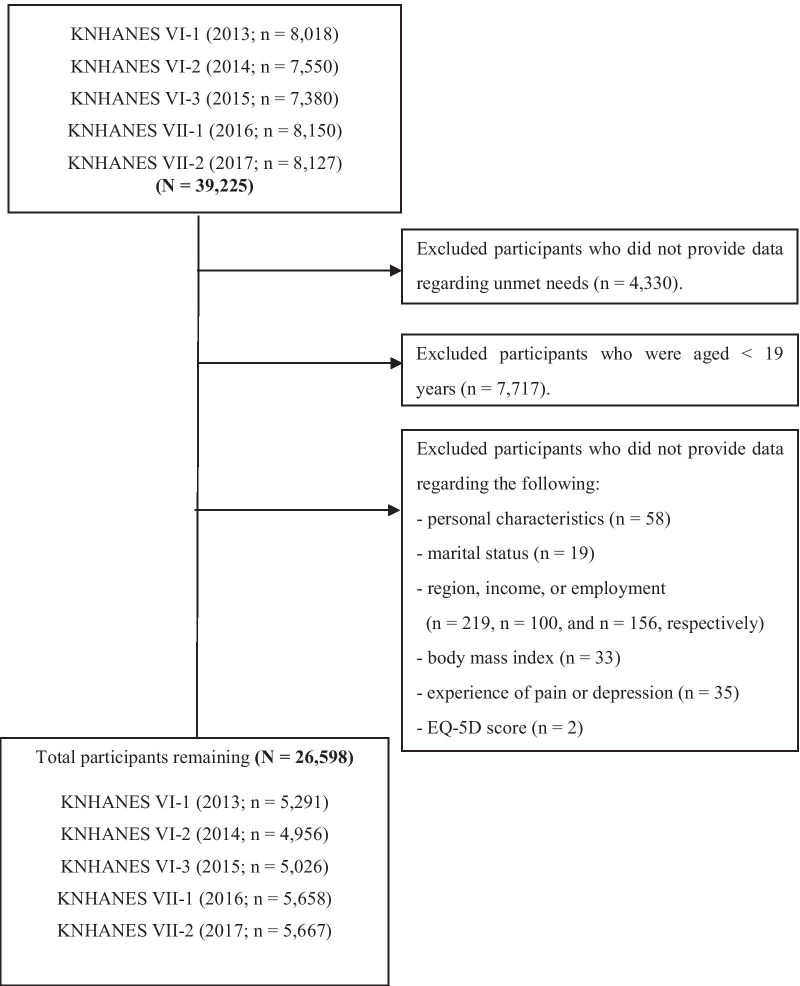

We analyzed data collected by KNHANES, which were originally sourced via three different methods: health-focused interviews, nutrition surveys, and health screenings. Since 1998, KNHANES has collected general population data concerning several indicators, including general health, health behaviors, and socio-demographic characteristics [14]. In the present study, we used data from 2013 to 2017 (waves VI and VII), which provided data for 26,598 adults (11,366 men and 15,232 women) aged ≥ 19 years. Individuals who did not respond to relevant items and those who provided invalid responses were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participant selection

Outcomes and other variables

Dependent variable

For our analysis, we set the dependent variable as whether a respondent had experienced unmet healthcare needs. The reasons for unmet healthcare needs were then divided into three subcategories (“economic,” “time,” and “other”), adopted from Chen and Hou [22]. Overall, the presence of unmet healthcare needs was measured by the question: “Over the past year, have you ever felt that you could not or did not access a medical service at the time when you needed it?” Respondents answered “yes” or “no.” Those who answered “yes” to the question were then asked to provide the reason: “What was the reason for which you did not receive the medical service you needed?” It is crucial to recognize the causes of unmet healthcare needs to achieve a holistic perspective of this matter [22, 23].

Economic reasons meant that the necessary service was not provided for economic reasons. Time reasons meant that the necessary service was not obtained owing to time-related aspects. Others include a variety of reasons, such as “mild symptoms,” “traffic,” “long waiting periods,” “difficulty in scheduling appointments,” “fear of treatment,” “and so on” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of self-reported unmet healthcare needs from the KNHANES 2013–2017

| Year | Stated reasons for unmet healthcare needs | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Time | Other | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 2013 | 205 | 29.50 | 217 | 31.22 | 273 | 39.28 | 695 |

| 2014 | 165 | 27.27 | 206 | 34.05 | 234 | 38.68 | 605 |

| 2015 | 165 | 25.70 | 211 | 32.87 | 266 | 41.43 | 642 |

| 2016 | 116 | 22.35 | 232 | 44.70 | 171 | 32.95 | 519 |

| 2017 | 91 | 17.14 | 251 | 47.27 | 189 | 35.59 | 531 |

| Total | 742 | 24.80 | 1117 | 37.33 | 1133 | 37.87 | 2992 |

Predictor variables

We used Anderson’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use to determine the risk factors that lead to unmet healthcare needs [24, 25]. This model is a framework designed to elucidate determinants associated with the use of health services, and it has been widely utilized in health-service-related research. The factors presented in Anderson’s model are classified into three categories.

(1) Predisposing factors These are basic personal characteristics that are largely unrelated to medical needs. Of these, this study included the following: sex (man/woman), age (19–39, 40–59, ≥ 60 years) [16], marital status (married and cohabiting; married and not cohabiting, bereaved, or divorced; unmarried), family type (solo, first generation, second generation, third generation or higher), and education level (elementary school or lower, middle school, high school, college or higher).

(2) Enabling factors These factors refer to the resources available to individuals and communities that facilitate access to medical services. Of these, this study included region (Seoul, metropolitan, or rural areas) [26, 27], employment status (“yes” or “no”), occupation type (“white collar,” “pink collar,” “blue collar,” or “unemployed or other”), income (i.e., income quartile; 4Q–1Q), health insurance type (“National Health Insurance [NHI],” “Medicaid,” or “no/do not know;” in South Korea, Medicaid is a type of health insurance funded by the federal and local government that provides health coverage for people with low income) [28], and whether the respondent had private insurance (“yes,” “no,” or “do not know”) [29]. By examining the enabling factors concerning region, employment type, income, and others, the uneven distribution of medical resources, which has been identified as a major challenge in South Korea, could be analyzed [27].

(3) Need factors These are associated with disabilities or behaviors that are directly related to the use of healthcare. We included smoking history (three groups: “current smoker,” “past smoker,” and “non-smoker”), alcohol consumption (“never drink,” “less than once per month,” “1–4 times per month,” and “ ≥ 5 times per month”), body mass index (“underweight,” “normal weight,” and “obese”), exercise level (“none,” “mild,” and “high”), self-rated health status (“very good,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “very poor”), stress level (“high,” “moderate,” “low,” and “none”), pain (“none,” “mild,” and “severe”), and depression (“none,” “mild,” and “severe”).

Statistical analysis

The KNHANES is based on a complex sample design; therefore, all data were analyzed through complex sample analysis, considering weights, stratification variables, and colony variables. A cross-tabulation (chi-square test of independence; χ2 test) of the complex sample analysis results (using various characteristics of the study respondents) was performed to identify generally perceived unmet healthcare needs. Using χ2 tests, categorical variables were presented as proportions (n, %), while continuous variables were expressed as estimate ± standard error (SE), using a linear model. In addition, risk factors related to unmet healthcare needs were analyzed using χ2 tests.

Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed after adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Additionally, all analyses were stratified by sex and age (19–39 years/40–59 years/ ≥ 60 years) to identify differences between sex and age regarding unmet healthcare needs. The equations of the logistic regression analyses are below, where is the probability that each individual i develops dementia:

| Model 1 |

| Model 2 |

| Model 3 |

The discriminatory power of the models was analyzed using a receiver operating characteristic curve; the area under the curve (AUC) was used to determine the model fit (the closer this value is to 1, the better the model fit). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

KNHANES waves VI and VII were conducted by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). All survey protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the KCDC (nos: 2013-07CON-03-4C, 2013-12EXP-03-5C, and 2015-01-02-6C). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to administering the KNHANES, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The original data are publicly available free of charge from the KNHANES website (http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr) for the purposes of academic research. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, which utilized data with encrypted personal information, it was exempted from ethical approval in writing by the Institutional Review Board of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine in Seoul, South Korea (no. 2019-08-001). All authors read and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki in preparing this study.

Results

A total of 26,598 adults participated in this study. After weighting was applied, the results represented an estimated 34,997,059 people. Of the 18,216,345 men represented, 1,530,845 (8.4%) reported having had unmet healthcare needs in the past year. Of the 18,942,760 women, 2,545,026 (13.4%) reported experiencing unmet healthcare needs in the past year.

Table 2 illustrates respondents’ general characteristics. In particular, it shows the prevalence of unmet healthcare needs concerning the three factor types (predisposing, enabling, and need).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population by sex (KNHANES 2013–2017)

| Men | Women | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes | p† | Total | No | Yes | p† | |||||

| N | n | (%)a | n | (%)a | N | n | (%)a | n | (%)a | |||

| Total | 18,216,345 | 16,685,501 | 91.6 | 1,530,845 | 8.4 | 18,942,760 | 16,397,734 | 86.6 | 2,545,026 | 13.4 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 19–39 | 7,134,247 | 6,454,879 | 90.5 | 679,368 | 9.5 | .002 | 6,729,728 | 5,815,876 | 86.4 | 913,851 | 13.6 | < .001 |

| 40–59 | 7,397,520 | 6,797,499 | 91.9 | 600,021 | 8.1 | 7,574,482 | 6,690,238 | 88.3 | 884,244 | 11.7 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 3,684,579 | 3,433,123 | 93.2 | 251,456 | 6.8 | 4,638,551 | 3,891,620 | 83.9 | 746,931 | 16.1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married and cohabiting | 12,153,503 | 11,199,408 | 92.1 | 954,095 | 7.9 | .005 | 12,472,117 | 10,964,171 | 87.9 | 1,507,946 | 12.1 | < .001 |

| Married but not cohabiting, or bereaved or divorced | 952,475 | 834,613 | 87.6 | 117,862 | 12.4 | 3,038,706 | 2,488,206 | 81.9 | 550,500 | 18.1 | ||

| Unmarried | 5,110,367 | 4,651,479 | 91.0 | 458,888 | 9.0 | 3,431,937 | 2,945,357 | 85.8 | 486,580 | 14.2 | ||

| Number of family members | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1,591,858 | 1,403,956 | 88.2 | 187,902 | 11.8 | .001 | 1,733,710 | 1,399,696 | 80.7 | 334,014 | 19.3 | < .001 |

| 2 | 4,332,376 | 4,020,407 | 92.8 | 311,969 | 7.2 | 4,626,732 | 4,034,561 | 87.2 | 592,171 | 12.8 | ||

| 3 | 5,039,486 | 4,572,429 | 90.7 | 467,057 | 9.3 | 5,253,312 | 4,536,896 | 86.4 | 716,416 | 13.6 | ||

| 4 | 5,425,420 | 4,996,671 | 92.1 | 428,749 | 7.9 | 5,208,615 | 4,608,789 | 88.5 | 599,826 | 11.5 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 1,827,206 | 1,692,037 | 92.6 | 135,168 | 7.4 | 2,120,391 | 1,817,791 | 85.7 | 302,600 | 14.3 | ||

| Family type | ||||||||||||

| Solo | 1,591,858 | 1,403,956 | 88.2 | 187,902 | 11.8 | .002 | 1,733,710 | 1,399,696 | 80.7 | 334,014 | 19.3 | < .001 |

| 1st generation | 3,627,903 | 3,370,651 | 92.9 | 257,253 | 7.1 | 3,424,477 | 2,990,585 | 87.3 | 433,891 | 12.7 | ||

| 2nd generation | 11,622,273 | 10,653,148 | 91.7 | 969,125 | 8.3 | 11,934,761 | 10,455,630 | 87.6 | 1,479,130 | 12.4 | ||

| 3rd generation or higher | 1,374,311 | 1,257,746 | 91.5 | 116,565 | 8.5 | 1,849,813 | 1,551,822 | 83.9 | 297,991 | 16.1 | ||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school or lower | 1,919,911 | 1,725,704 | 89.9 | 194,208 | 10.1 | .031 | 4,052,135 | 3,300,280 | 81.4 | 751,855 | 18.6 | < .001 |

| Middle school | 1,614,136 | 1,476,394 | 91.5 | 137,743 | 8.5 | 1,739,105 | 1,498,772 | 86.2 | 240,333 | 13.8 | ||

| High school | 7,092,204 | 6,459,846 | 91.1 | 632,358 | 8.9 | 6,544,948 | 5,762,870 | 88.1 | 782,078 | 11.9 | ||

| College or higher | 7,590,094 | 7,023,558 | 92.5 | 566,536 | 7.5 | 6,606,572 | 5,835,812 | 88.3 | 770,760 | 11.7 | ||

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Seoul | 3,712,026 | 3,429,116 | 92.4 | 282,910 | 7.6 | .212 | 3,957,342 | 3,451,044 | 87.2 | 506,298 | 12.8 | .574 |

| Metro | 4,379,973 | 4,029,841 | 92.0 | 350,132 | 8.0 | 4,656,018 | 4,033,340 | 86.6 | 622,678 | 13.4 | ||

| Rural | 10,124,346 | 9,226,543 | 91.1 | 897,803 | 8.9 | 10,329,400 | 8,913,350 | 86.3 | 1,416,050 | 13.7 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 4,465,236 | 4,143,690 | 92.8 | 321,546 | 7.2 | .022 | 9,248,403 | 8,056,557 | 87.1 | 1,191,846 | 12.9 | .111 |

| Employed | 13,751,109 | 12,541,811 | 91.2 | 1,209,299 | 8.8 | 9,694,357 | 8,341,177 | 86.0 | 1,353,180 | 14.0 | ||

| Incomeb | ||||||||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 4,550,538 | 4,115,607 | 90.4 | 434,930 | 9.6 | .017 | 4,701,072 | 3,866,590 | 82.2 | 834,483 | 17.8 | < .001 |

| 2Q | 4,548,682 | 4,153,534 | 91.3 | 395,148 | 8.7 | 4,738,686 | 4,088,322 | 86.3 | 650,364 | 13.7 | ||

| 3Q | 4,512,661 | 4,126,987 | 91.5 | 385,674 | 8.5 | 4,733,493 | 4,127,687 | 87.2 | 605,805 | 12.8 | ||

| 4Q (highest) | 4,604,465 | 4,289,372 | 93.2 | 315,093 | 6.8 | 4,769,509 | 4,315,135 | 90.5 | 454,374 | 9.5 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| White collar | 5,675,473 | 5,225,634 | 92.1 | 449,840 | 7.9 | .026 | 4,210,948 | 3,697,355 | 87.8 | 513,592 | 12.2 | .001 |

| Pink collar | 2,157,717 | 1,986,487 | 92.1 | 171,230 | 7.9 | 2,787,396 | 2,415,371 | 86.7 | 372,024 | 13.3 | ||

| Blue collar | 5,157,143 | 4,647,831 | 90.1 | 509,312 | 9.9 | 2,234,315 | 1,856,211 | 83.1 | 378,104 | 16.9 | ||

| Unemployed or other | 5,226,012 | 4,825,549 | 92.3 | 400,463 | 7.7 | 9,710,102 | 8,428,797 | 86.8 | 1,281,306 | 13.2 | ||

| Medical Insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 17,520,008 | 16,080,991 | 91.8 | 1,439,016 | 8.2 | .025 | 18,075,601 | 15,743,253 | 87.1 | 2,332,347 | 12.9 | < .001 |

| Medicaid | 494,275 | 430,209 | 87.0 | 64,066 | 13.0 | 646,528 | 474,806 | 73.4 | 171,722 | 26.6 | ||

| No/do not know | 202,063 | 174,300 | 86.3 | 27,762 | 13.7 | 220,631 | 179,675 | 81.4 | 40,956 | 18.6 | ||

| Private insurance | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 14,384,239 | 13,223,721 | 91.9 | 1,160,517 | 8.1 | .094 | 15,011,361 | 13,156,749 | 87.6 | 1,854,612 | 12.4 | < .001 |

| No | 3,638,702 | 3,284,231 | 90.3 | 354,471 | 9.7 | 3,771,901 | 3,104,828 | 82.3 | 667,073 | 17.7 | ||

| Do not know | 193,404 | 177,548 | 91.8 | 15,856 | 8.2 | 159,498 | 136,157 | 85.4 | 23,341 | 14.6 | ||

| Smoking history | ||||||||||||

| Non-smoker | 4,504,920 | 4,195,041 | 93.1 | 309,879 | 6.9 | < .001 | 16,636,672 | 14,478,079 | 87.0 | 2,158,593 | 13.0 | < .001 |

| Past smoker | 6,460,273 | 6,014,161 | 93.1 | 446,113 | 6.9 | 1,120,625 | 959,229 | 85.6 | 161,396 | 14.4 | ||

| Current smoker | 7,251,152 | 6,476,300 | 89.3 | 774,853 | 10.7 | 1,185,463 | 960,426 | 81.0 | 225,038 | 19.0 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never drink | 2,633,850 | 2,430,482 | 92.3 | 203,368 | 7.7 | .544 | 6,116,013 | 5,184,505 | 84.8 | 931,508 | 15.2 | < .001 |

| Less than 1 time per month | 2,040,101 | 1,872,840 | 91.8 | 167,261 | 8.2 | 4,465,941 | 3,957,458 | 88.6 | 508,483 | 11.4 | ||

| 1–4 times per month | 7,012,060 | 6,386,257 | 91.1 | 625,803 | 8.9 | 6,068,744 | 5,279,258 | 87.0 | 789,486 | 13.0 | ||

| ≥ 5 times per month | 6,530,334 | 5,995,922 | 91.8 | 534,412 | 8.2 | 2,292,062 | 1,976,513 | 86.2 | 315,549 | 13.8 | ||

| Body mass index | ||||||||||||

| Normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25) | 10,540,097 | 9,671,147 | 91.8 | 868,950 | 8.2 | .168 | 12,549,645 | 10,972,946 | 87.4 | 1,576,699 | 12.6 | .001 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 510,387 | 448,310 | 87.8 | 62,077 | 12.2 | 1,174,258 | 978,254 | 83.3 | 196,005 | 16.7 | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 25) | 7,165,862 | 6,566,044 | 91.6 | 599,817 | 8.4 | 5,218,856 | 4,446,534 | 85.2 | 772,323 | 14.8 | ||

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| None | 16,706,537 | 15,445,099 | 92.4 | 1,261,438 | 7.6 | < .001 | 16,274,205 | 14,414,380 | 88.6 | 1,859,825 | 11.4 | < .001 |

| Mild | 1,456,613 | 1,203,825 | 82.6 | 252,789 | 17.4 | 2,523,305 | 1,899,396 | 75.3 | 623,909 | 24.7 | ||

| High | 53,195 | 36,577 | 68.8 | 16,618 | 31.2 | 145,250 | 83,958 | 57.8 | 61,292 | 42.2 | ||

| Stress level | ||||||||||||

| High | 4,646,371 | 3,975,432 | 85.6 | 670,939 | 14.4 | < .001 | 5,380,940 | 4,288,734 | 79.7 | 1,092,207 | 20.3 | < .001 |

| Moderate | 10,652,409 | 9,903,651 | 93.0 | 748,758 | 7.0 | 10,725,638 | 9,520,775 | 88.8 | 1,204,863 | 11.2 | ||

| Low | 2,822,867 | 2,717,241 | 96.3 | 105,626 | 3.7 | 2,713,771 | 2,483,941 | 91.5 | 229,830 | 8.5 | ||

| None | 94,698 | 89,177 | 94.2 | 5,521 | 5.8 | 122,410 | 104,284 | 85.2 | 18,126 | 14.8 | ||

| Self-rated health status | ||||||||||||

| Very good/good | 6,366,031 | 6,067,433 | 95.3 | 298,597 | 4.7 | < .001 | 5,168,004 | 4,835,422 | 93.6 | 332,582 | 6.4 | < .001 |

| Fair | 9,202,108 | 8,432,601 | 91.6 | 769,507 | 8.4 | 9,947,397 | 8,705,500 | 87.5 | 1,241,897 | 12.5 | ||

| Poor/very poor | 2,648,207 | 2,185,466 | 82.5 | 462,741 | 17.5 | 3,827,359 | 2,856,812 | 74.6 | 970,547 | 25.4 | ||

| Pain | ||||||||||||

| None | 15,243,143 | 14,284,214 | 93.7 | 958,930 | 6.3 | < .001 | 13,975,362 | 12,620,501 | 90.3 | 1,354,861 | 9.7 | < .001 |

| Mild | 2,775,714 | 2,247,400 | 81.0 | 528,313 | 19.0 | 4,494,769 | 3,470,452 | 77.2 | 1,024,317 | 22.8 | ||

| Severe | 197,488 | 153,887 | 77.9 | 43,602 | 22.1 | 472,629 | 306,781 | 64.9 | 165,848 | 35.1 | ||

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| None | 16,948,918 | 15,666,651 | 92.4 | 1,282,267 | 7.6 | < .001 | 16,579,396 | 14,703,608 | 88.7 | 1,875,788 | 11.3 | < .001 |

| Mild | 1,202,449 | 976,826 | 81.2 | 225,623 | 18.8 | 2,184,118 | 1,593,660 | 73.0 | 590,458 | 27.0 | ||

| Severe | 64,978 | 42,023 | 64.7 | 22,955 | 35.3 | 179,245 | 100,466 | 56.0 | 78,779 | 44.0 | ||

A chi-square test was performed to determine the differences between groups with and without unmet needs

NHI National Health Insurance, Q quartile

aWeighted (%)

bIncome divided by quartile

Concerning sex, women were more likely to experience unmet healthcare needs than men. Within that group, participants aged 60 years and older experienced the highest rate of unmet healthcare needs. For men, the younger age group (19–39 years) experienced the highest rate of unmet healthcare needs as compared to their counterparts. Furthermore, marital status influenced both sexes: singles (separated, widowed, or divorced) experienced more unmet healthcare needs than those who were married. Similarly, for both sexes, single-person families had higher rates of unmet healthcare needs (men: 11.8%; women: 19.3%) as compared to their counterparts. Further, among men and women, those who had the lowest education level (elementary school or below) had the highest levels of unmet healthcare needs (men: 10.1%; women: 18.6%) as compared to their counterparts.

Both men and women from rural areas were more likely to experience unmet healthcare needs when compared to those from other regions (men: 8.9%; women: 13.7%). Regarding women’s income, those with the lowest income showed the highest rate of unmet healthcare needs (17.8%) as compared to their counterparts. By contrast, for men, the rate of unmet healthcare needs did not vary significantly among the income quartile groups. Concerning occupation for both sexes, the blue-collar worker group had the most unmet healthcare needs (men: 9.9%; women: 16.9%) as compared to their counterparts. Regarding health insurance for both sexes, Medicaid beneficiaries had the highest rate when compared to beneficiaries of other types of health insurance (men: 13.0%; women: 26.6%). Finally, women who did not have private insurance had a higher rate of unmet healthcare needs compared to those who had some form of insurance (women: 17.7%).

Regarding need factors, both male and female smokers were more likely to experience unmet healthcare needs (men: 10.7%; women: 19.0%) as compared to their counterparts. In the drinking category, there was no significant difference among the men; however, non-drinking women experienced more unmet healthcare needs (women: 15.2%, p < 0.001) as compared to their counterparts. Body mass index showed no significance among men; however, underweight and obese women experienced more unmet healthcare needs than women who had normal body weight. For both sexes, those who engaged in high levels of exercise and who had high stress levels showed higher rates of unmet healthcare needs as compared to their counterparts. Finally, those who considered themselves to have a poor health status and those who experienced severe pain and depression were more likely to experience unmet healthcare needs as compared to their counterparts.

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression model. Model 1 was adjusted by sex, age, marital status, family members, and education level. Model 2 was adjusted by Model 1 as well as region, economic activity, income, occupation, medical insurance type, and private insurance. Model 3 was adjusted by Model 2 as well as smoking, drinking, obesity, exercise, self-rated health status, stress level, pain, and depression. The explanatory power demonstrated improvement in the progression from Model 1 to Model 3 (AUCs of Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3 were 0.600, 0.612, and 0.700, respectively).

Table 3.

Overall unmet needs according to the analysis model

| Variables | Unmet needs, based on KNHANES 2013–2017 data | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Female | 1.55 | 1.41 | 1.71 | < .001 | 1.72 | 1.55 | 1.90 | < .001 | 1.64 | 1.43 | 1.87 | < .001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 19–39 | 1.76 | 1.49 | 2.08 | < .001 | 1.59 | 1.33 | 1.90 | < .001 | 1.60 | 1.33 | 1.92 | < .001 |

| 40–59 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.45 | .001 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.31 | .086 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.36 | .040 |

| ≥ 60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married and cohabiting | 1.03 | 0.89 | 1.19 | .716 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.19 | .763 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.16 | .995 |

| Married but not cohabiting, or bereaved or divorced | 1.35 | 1.11 | 1.63 | .002 | 1.24 | 1.03 | 1.50 | .025 | 1.08 | 0.89 | 1.32 | .427 |

| Unmarried | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Number of family members | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.29 | 1.05 | 1.57 | .014 | 1.17 | 0.95 | 1.43 | .144 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.31 | .612 |

| 2 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 1.06 | .204 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 1.03 | .111 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.97 | .020 |

| 3 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.28 | .345 | 1.09 | 0.92 | 1.29 | .322 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 1.24 | .663 |

| 4 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.09 | .336 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.12 | .506 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.10 | .401 |

| ≥ 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school or lower | 2.08 | 1.78 | 2.43 | < .001 | 1.70 | 1.44 | 2.02 | < .001 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.43 | .050 |

| Middle school | 1.44 | 1.21 | 1.72 | < .001 | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.51 | .019 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.21 | .975 |

| High school | 1.16 | 1.03 | 1.30 | .017 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.23 | .214 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.17 | .752 |

| College or higher | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Seoul | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Metro | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.18 | .486 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.21 | .301 | ||||

| Rural | 0.99 | 0.86 | 1.15 | .904 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 1.22 | .541 | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.53 | 1.23 | 1.90 | < .001 | 1.74 | 1.38 | 2.18 | < .001 | ||||

| Income | ||||||||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 1.45 | 1.26 | 1.67 | < .001 | 1.29 | 1.11 | 1.49 | .001 | ||||

| 2Q | 1.26 | 1.10 | 1.45 | .001 | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.36 | .020 | ||||

| 3Q | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.45 | .001 | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.37 | .017 | ||||

| 4Q (highest) | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| White collar | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Pink collar | 1.23 | 0.96 | 1.57 | .106 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.66 | .052 | ||||

| Blue collar | 1.15 | 0.98 | 1.35 | .087 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.43 | .015 | ||||

| Unemployed or other | 0.95 | 0.81 | 1.13 | .573 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.13 | .559 | ||||

| Medical insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Medicaid | 1.64 | 1.31 | 2.06 | < .001 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.80 | .456 | ||||

| No/do not know | 1.30 | 0.85 | 1.97 | .222 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.31 | .803 | ||||

| Private insurance | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| No | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.35 | .004 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.29 | .045 | ||||

| Do not know | 0.91 | 0.57 | 1.44 | .692 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 1.65 | .996 | ||||

| Smoking history | ||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.46 | .003 | ||||||||

| Past smoker | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 | .419 | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never drink | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Less than one time per month | 0.93 | 0.79 | 1.08 | .327 | ||||||||

| 1–4 times per month | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.18 | .462 | ||||||||

| ≥ 5 times per month | 0.88 | 0.76 | 1.01 | .069 | ||||||||

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||||||||||

| Normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25) | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Under weight (BMI < 18.5) | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.06 | .374 | ||||||||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 25) | 1.17 | 0.94 | 1.47 | .162 | ||||||||

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Mild | 1.96 | 1.30 | 2.95 | .001 | ||||||||

| High | 1.31 | 1.13 | 1.52 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Self-rated health status | ||||||||||||

| Very poor | 3.62 | 2.46 | 5.32 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Poor | 3.47 | 2.44 | 4.95 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Fair | 2.25 | 1.61 | 3.14 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Good | 1.44 | 1.02 | 2.04 | .038 | ||||||||

| Very good | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Stress level | ||||||||||||

| High | 2.35 | 1.28 | 4.30 | .006 | ||||||||

| Moderate | 1.56 | 0.85 | 2.87 | .150 | ||||||||

| Low | 1.16 | 0.63 | 2.15 | .636 | ||||||||

| None | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Pain | ||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Mild | 2.09 | 1.61 | 2.72 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Severe | 2.06 | 1.83 | 2.31 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Light | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Moderate | 1.45 | 1.26 | 1.65 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Heavy/extreme | 1.78 | 1.23 | 2.57 | .002 | ||||||||

| AUCa | 0.600 | 0.612 | 0.700 | |||||||||

Logistic regression analysis with a complex sampling design was performed by adjusting for covariates

Model 1 was adjusted for sex, age, marital status, number of family members, and education level

Model 2 was adjusted for Model 1, as well as region, economic activity, income, occupation, medical insurance type, and private insurance

Model 3 was adjusted for Model 1 and Model 2, as well as smoking, drinking, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health status, stress level, pain, and depression

NHI National Health Insurance, Q quartile, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, AUC area under the receiver, OR 95%, CI 95%

aThe AUC operating characteristic curve indicates the discrimination ability of the prediction model

Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression model by sex. In both the male and female groups, younger people (age: 19–39) had a higher odds ratio (OR) of experiencing unmet healthcare needs compared to older people (reference: age ≥ 60) (men: OR 1.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.35–2.48; women: OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.12–1.81). Both groups showed a higher tendency of unmet healthcare needs when the individuals were unemployed (men: OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.38–2.71; women: OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.22–2.25). In particular, unlike men, women’s unmet healthcare needs increased as their incomes decreased (1Q OR 1.55, 2Q OR 1.29, 3Q OR 1.26). Only male smokers showed higher unmet healthcare needs compared to non-smokers (men: OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.02–1.58). Men and women showed a tendency to have more unmet healthcare needs with less exercise, worse subjective health state, worse pain, and a higher degree of depression. The significance of the interaction term was tested with the likelihood test, and if it was significant, each term was analyzed by post-mortem analysis. As a result of the likelihood test, the interaction terms according to all covariates were significant. In particular, the higher the level of education, income, and pain, the higher the odds ratio for unmet medical care for women.

Table 4.

Overall unmet needs by sex

| Variables | Unmet needs, based on KNHANES 2013–2017 data | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | ||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 19–39 | 1.60 | 1.33 | 1.92 | < .001 | 1.83 | 1.35 | 2.48 | < .001 | 1.42 | 1.12 | 1.81 | .004 |

| 40–59 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.36 | .040 | 1.31 | 1.02 | 1.67 | .036 | 1.10 | 0.91 | 1.34 | .334 |

| ≥ 60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married and cohabiting | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.16 | .995 | 1.11 | 0.86 | 1.44 | .414 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 1.11 | .397 |

| Married but not cohabiting, or bereaved or divorced | 1.08 | 0.89 | 1.32 | .427 | 1.30 | 0.89 | 1.90 | .172 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 1.18 | .594 |

| Unmarried | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Number of family members | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.31 | .612 | 1.43 | 0.98 | 2.08 | .065 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 1.13 | .316 |

| 2 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.97 | .020 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.40 | .889 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.89 | .002 |

| 3 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 1.24 | .663 | 1.33 | 0.99 | 1.79 | .059 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.12 | .375 |

| 4 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.10 | .401 | 1.15 | 0.85 | 1.58 | .368 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 1.02 | .080 |

| ≥ 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school or lower | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.43 | .050 | 1.22 | 0.89 | 1.67 | .224 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 1.44 | .246 |

| Middle school | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.21 | .975 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 1.44 | .820 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 1.24 | .807 |

| High school | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.17 | .752 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 1.43 | .195 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.11 | .442 |

| College or higher | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Seoul | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Metro | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.21 | .301 | 1.13 | 0.92 | 1.38 | .252 | 1.02 | 0.87 | 1.19 | .827 |

| Rural | 1.05 | 0.90 | 1.22 | .541 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 1.33 | .718 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 1.23 | .751 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.74 | 1.38 | 2.18 | < .001 | 1.93 | 1.38 | 2.71 | < .001 | 1.65 | 1.22 | 2.25 | .001 |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 1.29 | 1.11 | 1.49 | .001 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.29 | .969 | 1.55 | 1.29 | 1.86 | < .001 |

| 2Q | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.36 | .020 | 1.05 | 0.83 | 1.34 | .667 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 1.53 | .004 |

| 3Q | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.37 | .017 | 1.11 | 0.88 | 1.39 | .391 | 1.26 | 1.06 | 1.50 | .010 |

| 4Q (highest) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| White collar | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Pink collar | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.66 | .052 | 1.31 | 0.91 | 1.88 | .149 | 1.30 | 0.92 | 1.83 | .140 |

| Blue collar | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.43 | .015 | 1.22 | 0.97 | 1.53 | .095 | 1.21 | 0.96 | 1.52 | .106 |

| Unemployed or other | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.13 | .559 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 1.20 | .468 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.25 | .906 |

| Medical insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Medicaid | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.80 | .456 | 1.54 | 0.75 | 3.17 | .235 | 1.16 | 0.89 | 1.50 | .275 |

| No/do not know | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.31 | .803 | 0.90 | 0.56 | 1.46 | .674 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 1.54 | .887 |

| Private insurance | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| No | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.29 | .045 | 1.19 | 0.95 | 1.49 | .134 | 1.13 | 0.97 | 1.32 | .130 |

| Do not know | 1.00 | 0.61 | 1.65 | .996 | 1.07 | 0.47 | 2.45 | .868 | 0.96 | 0.53 | 1.75 | .892 |

| Smoking history | ||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.46 | .003 | 1.27 | 1.02 | 1.58 | .033 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 1.51 | .115 |

| Past smoker | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 | .419 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 1.25 | .878 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 1.14 | .362 |

| Non-smoker | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never drink | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Less than once per month | 0.93 | 0.79 | 1.08 | .327 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 1.28 | .913 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.17 | .682 |

| 1–4 times per month | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.18 | .462 | 1.23 | 0.95 | 1.59 | .119 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 1.14 | .801 |

| ≥ 5 times per month | 0.88 | 0.76 | 1.01 | .069 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 1.44 | .834 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.98 | .025 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||||||||||

| Normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Under weight (BMI < 18.5) | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.06 | .374 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 1.08 | .279 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.10 | .687 |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 25) | 1.17 | 0.94 | 1.47 | .162 | 1.14 | 0.70 | 1.85 | .604 | 1.21 | 0.94 | 1.55 | .147 |

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Mild | 1.31 | 1.13 | 1.52 | < .001 | 1.36 | 1.03 | 1.80 | .029 | 1.30 | 1.09 | 1.55 | .004 |

| High | 1.96 | 1.30 | 2.95 | .001 | 2.95 | 1.16 | 7.51 | .023 | 1.78 | 1.16 | 2.74 | .009 |

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Very poor | 3.62 | 2.46 | 5.32 | < .001 | 3.22 | 1.62 | 6.40 | .001 | 3.84 | 2.37 | 6.23 | < .001 |

| Poor | 3.47 | 2.44 | 4.95 | < .001 | 3.52 | 2.00 | 6.22 | < .001 | 3.52 | 2.24 | 5.52 | < .001 |

| Fair | 2.25 | 1.61 | 3.14 | < .001 | 2.19 | 1.27 | 3.77 | .005 | 2.30 | 1.50 | 3.54 | < .001 |

| Good | 1.44 | 1.02 | 2.04 | .038 | 1.56 | 0.90 | 2.73 | .116 | 1.35 | 0.86 | 2.13 | .188 |

| Very good | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Stress level | ||||||||||||

| High | 2.35 | 1.28 | 4.30 | .006 | 2.97 | 0.78 | 11.34 | .111 | 2.14 | 1.08 | 4.26 | .030 |

| Moderate | 1.56 | 0.85 | 2.87 | .150 | 1.74 | 0.46 | 6.62 | .414 | 1.55 | 0.78 | 3.09 | .213 |

| Low | 1.16 | 0.63 | 2.15 | .636 | 1.15 | 0.30 | 4.51 | .837 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 2.52 | .534 |

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Pain | ||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Mild | 2.06 | 1.83 | 2.31 | < .001 | 1.98 | 1.02 | 3.86 | .044 | 1.81 | 1.57 | 2.09 | < .001 |

| Severe | 2.09 | 1.61 | 2.72 | < .001 | 2.56 | 2.09 | 3.13 | < .001 | 2.04 | 1.56 | 2.66 | < .001 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Light | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Moderate | 1.45 | 1.26 | 1.65 | < .001 | 1.34 | 1.02 | 1.76 | .039 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 1.80 | < .001 |

| Heavy/extreme | 1.78 | 1.23 | 2.57 | .002 | 2.02 | 0.92 | 4.45 | .081 | 1.76 | 1.16 | 2.66 | .008 |

Logistic regression analysis with a complex sampling design was performed by adjusting for covariates

The significance of the interaction term was tested with the likelihood test, and if it was significant, each term was analyzed by post-mortem analysis

Model was adjusted for sex, age, marital status, number of family members, education level, region, economic activity, income, occupation, medical insurance type, private insurance, smoking, drinking, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health status, stress level, pain, and depression

NHI National Health Insurance, Q quartile, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Table 5 shows the results of the logistic regression model according to age group. Women had higher odds of experiencing unmet healthcare needs compared to men, regardless of age. Young and older adult age groups (19–39 years/40–59 years) showed a tendency to have more unmet healthcare needs when they were unemployed (19–39 years: OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.17–2.01; 40–59 years: OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.63–3.36).

Table 5.

Overall unmet needs according to age group in the KNHANES 2013–2017

| Variables | Unmet needs, KNHANES 2013–2017 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–39 years | 40–59 years | ≥ 60 years | ||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Female | 1.67 | 1.25 | 2.22 | .001 | 1.60 | 1.25 | 2.06 | < .001 | 1.55 | 1.26 | 1.90 | < .001 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married-cohabiting | 0.82 | 0.34 | 1.97 | .651 | 1.63 | 1.07 | 2.50 | .024 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.11 | .426 |

| Married-no cohabiting, bereaved, or divorced | 0.84 | 0.36 | 1.98 | .692 | 1.71 | 1.11 | 2.64 | .016 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 1.28 | .200 |

| Unmarried | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Number of family members | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.10 | 0.75 | 1.62 | .616 | 1.27 | 0.85 | 1.91 | .239 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.28 | .504 |

| 2 | 0.87 | 0.61 | 1.23 | .421 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 1.14 | .280 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.99 | .044 |

| 3 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.34 | .653 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 1.37 | .804 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.37 | .657 |

| 4 | 1.20 | 0.78 | 1.83 | .410 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 1.30 | .854 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.07 | .145 |

| ≥ 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school or less | 1.74 | 1.13 | 2.67 | .012 | 1.09 | 0.82 | 1.46 | .548 | 0.87 | 0.38 | 2.02 | .745 |

| Middle school | 1.52 | 0.95 | 2.42 | .080 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 1.22 | .644 | 0.99 | 0.56 | 1.74 | .977 |

| High school | 1.45 | 0.92 | 2.28 | .107 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.22 | .989 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 1.21 | .918 |

| College or over | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Seoul | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Metro | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.24 | .965 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.29 | .717 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 1.40 | .191 |

| Rural | 0.86 | 0.66 | 1.12 | .256 | 1.17 | 0.91 | 1.50 | .215 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 1.30 | .794 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.53 | 1.17 | 2.01 | .002 | 2.34 | 1.63 | 3.36 | < .001 | 0.75 | 0.21 | 2.70 | .657 |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 1.38 | 1.06 | 1.79 | .018 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.60 | .060 | 1.30 | 1.01 | 1.68 | .040 |

| 2Q | 1.19 | 0.92 | 1.54 | .190 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 1.32 | .646 | 1.31 | 1.03 | 1.68 | .031 |

| 3Q | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.32 | .850 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.31 | .787 | 1.44 | 1.15 | 1.81 | .002 |

| 4Q (highest) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| White collar | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Pink collar | 1.06 | 0.60 | 1.87 | .847 | 1.88 | 1.29 | 2.75 | .001 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 2.04 | .381 |

| Blue collar | 1.27 | 0.73 | 2.19 | .396 | 1.36 | 1.07 | 1.74 | .013 | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.44 | .598 |

| Unemployed or other | 1.16 | 0.64 | 2.09 | .628 | 1.03 | 0.79 | 1.34 | .814 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 1.10 | .216 |

| Medical insurance type | ||||||||||||

| NHI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Medicaid | 1.31 | 0.79 | 2.18 | .291 | 1.05 | 0.40 | 2.75 | .919 | 1.10 | 0.49 | 2.44 | .819 |

| No/do not know | 1.20 | 0.89 | 1.62 | .238 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 1.47 | .813 | 1.15 | 0.59 | 2.25 | .685 |

| Private insurance | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.81 | 0.41 | 1.58 | .530 | 1.47 | 0.39 | 5.52 | .569 | 1.09 | 0.52 | 2.30 | .821 |

| No | 1.16 | 0.97 | 1.38 | .098 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.53 | .200 | 1.16 | 0.90 | 1.50 | .244 |

| Do not know | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Smoking history | ||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 1.22 | 0.89 | 1.66 | .211 | 1.34 | 1.03 | 1.74 | .029 | 1.25 | 0.99 | 1.58 | .061 |

| Past smoker | 0.70 | 0.52 | .93 | .015 | 1.06 | 0.81 | 1.39 | .653 | 1.01 | 0.78 | 1.30 | .962 |

| Non-smoker | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never drink | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Less than 1 time per month | 1.11 | 0.87 | 1.41 | .410 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.93 | .010 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 1.31 | .904 |

| 1–4 times per month | 1.10 | 0.89 | 1.36 | .368 | 1.03 | 0.84 | 1.25 | .802 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 1.22 | .757 |

| ≥ 5 times per month | 1.08 | 0.86 | 1.35 | .498 | 0.89 | 0.70 | 1.12 | .313 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.96 | .024 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||||||||||

| Normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Under weight (BMI < 18.5) | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.13 | .689 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 1.15 | .734 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 1.10 | .300 |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 25) | 0.93 | 0.60 | 1.45 | .750 | 1.11 | 0.73 | 1.71 | .618 | 1.22 | 0.91 | 1.65 | .185 |

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| None | 2.56 | 1.62 | 4.05 | < .001 | 0.66 | 0.21 | 2.06 | .473 | 2.03 | 0.23 | 17.92 | .523 |

| Mild | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.67 | .001 | 1.12 | 0.87 | 1.45 | .385 | 1.79 | 1.23 | 2.59 | .002 |

| High | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||

| Very poor | 3.32 | 1.63 | 6.75 | .001 | 4.40 | 2.29 | 8.48 | < .001 | 4.77 | 2.75 | 8.25 | < .001 |

| Poor | 2.90 | 1.45 | 5.80 | .003 | 2.85 | 1.62 | 5.04 | < .001 | 2.47 | 1.06 | 5.78 | .036 |

| Fair | 2.35 | 1.18 | 4.71 | .016 | 2.06 | 1.20 | 3.54 | .009 | 2.38 | 1.42 | 3.99 | .001 |

| Good | 1.82 | 0.88 | 3.77 | .108 | 1.36 | 0.76 | 2.40 | .297 | 1.44 | 0.86 | 2.41 | .168 |

| Very good | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Stress level | ||||||||||||

| High | 2.75 | 1.36 | 5.56 | .005 | 1.62 | 0.41 | 6.46 | .492 | 2.97 | 0.44 | 19.86 | .261 |

| Moderate | 1.90 | 0.94 | 3.85 | .073 | 1.04 | 0.26 | 4.18 | .954 | 2.07 | 0.31 | 13.90 | .454 |

| Low | 1.53 | 0.74 | 3.15 | .246 | 0.64 | 0.16 | 2.62 | .532 | 1.67 | 0.24 | 11.70 | .604 |

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Pain | ||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Mild | 1.95 | 1.60 | 2.39 | < .001 | 1.94 | 1.09 | 3.46 | .024 | 1.69 | 0.52 | 5.43 | .382 |

| Severe | 2.17 | 1.60 | 2.96 | < .001 | 2.15 | 1.79 | 2.58 | < .001 | 2.04 | 1.65 | 2.51 | < .001 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Light | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Moderate | 1.45 | 0.97 | 2.19 | .072 | 2.99 | 1.33 | 6.74 | .008 | 2.03 | 0.63 | 6.57 | .236 |

| Severe | 1.63 | 1.34 | 1.98 | < .001 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 1.63 | .043 | 1.57 | 1.22 | 2.01 | < .001 |

Logistic regression analysis with complex sampling design was performed by adjusting for covariates

Model 1 was adjusted by sex, age, marital status, family number and education level

Model 2 was adjusted by Model 1 as well as region, economic activity, income, occupation, medical insurance type and private insurance

Model 3 was adjusted by Model 2 as well as smoking, drink, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health status, stress level, pain and depression

NHI National Health Insurance, Q quartile, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, OR 95%, CI 95%

The factors affecting unmet healthcare needs differed by age groups. Education was the only significant factor in the younger age group (19–39 years). Individuals who received less than an elementary school education experienced more unmet healthcare needs compared with individuals who had college or higher education degrees (elementary school or less: OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.13–2.67). Furthermore, the high exercise group experienced more unmet healthcare needs than did their counterparts (none: OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.62–4.05; mild: OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.13–1.67), and there were more unmet healthcare needs with increased stress (high: OR 2.75).

Some factors were only significant in the group aged 40–59 years, who are economic activity ishigh. Compared to the white-collar group, the pink and the blue-collar groups with more physical activity experienced more unmet healthcare needs (pink collar: OR 1.88; blue collar: OR 1.36). Smokers experienced more unmet healthcare needs compared to the non-smokers (current smokers: OR 1.34). Concerning marital status, the married-no cohabitation, divorced, or bereaved group experienced more unmet healthcare needs compared to the unmarried group (married-no cohabitation, bereaved, or divorced: OR 1.71) In particular, individuals with lower income from the older group showed a clear tendency to experience more unmet healthcare needs (1Q (lowest): OR 1.30/ 2Q: OR 1.31/ 3Q: OR 1.44). Regardless of age, all groups showed a tendency to have more unmet healthcare needs with a worse subjective health state, worse pain, and a worse degree of depression.

Discussion

This study analyzed the determinants of unmet healthcare needs among South Korean adults using KNHANES data for 2013–2017. In 2017, 9.5% of the sample experienced unmet healthcare needs. This percentage was 12.5% in 2013, which indicates that there has been an overall decline in unmet healthcare needs (see Additional files 1 and 2). This decline indicates the efficiency of the policies (such as reinforcement NHI coverage and an out-of-pocket limit) that have been implemented in South Korea in an attempt to reduce medical expenses [30, 31]. Previous studies have indicated that most of the reasons for unmet healthcare needs were economic-related; however, the recent data from 2017 showed that other reasons surpassed the economic reasons. One such determinant can be found based on the results of a recent domestic study, which reported that “time constraints” are the primary reason for unmet healthcare needs [10]. In our study, we showed that unsatisfactory medical care has significantly increased since 2013 because of time reasons rather than economic reasons (Table 1). This suggests that determinants besides economic factors should be considered to resolve unmet healthcare needs. However, it is important to focus not only on financial barriers, as the traditional policies have done, but also on other barriers. Based on our findings, we make the following three policy proposals.

Improvement of policies concerning predisposing factors, particularly for women and younger age groups

We found that, compared to men, women experienced more unmet healthcare needs. Many women, especially mothers, feel that there are multiple barriers to their personal healthcare because they play a dual role, comprising responsibilities at work and at home, which impairs their ability to care for themselves [32]. Other studies have reported that women have traditionally been unable to obtain timely medical care because of their role as family “caretakers” [33]. Women in South Korean culture in particular, which is influenced by Confucian patriarchal values, tend to prioritize the medical needs of other family members over their own [34], and older women have been reported to have higher unmet healthcare needs as compared to younger women [14]. Moreover, compared to men, women may be more likely to experience a financial burden as a result of their lower social status, which causes restrictions on their social participation [35] and low health-related literacy [36, 37]. Due to this, women earn less and are financially dependent on their spouses.

Our results also showed that the younger group had greater odds of experiencing unmet healthcare needs than their older counterparts. There was a significant increase in use and access reasons as age increased. Previous studies reported that younger adults experienced less use- and access-related unmet healthcare needs than older adults, who experience relatively more health problems, regardless of sex [38, 39]. This can be interpreted as indicating that younger individuals more actively search for the medical services they require [40], have higher expectations regarding the quality of their healthcare, and have a greater likelihood of complaining when they are not satisfied with their health services [26, 41, 42].

Policies that focus on the enabling factors, specifically low socioeconomic status, should be improved

Our results demonstrated that unemployment, low income, and blue-collar jobs (which involve heavy labor) are more likely to result in unmet healthcare needs (Table 4). According to an OECD report, people with low socioeconomic status are less likely to seek medical services they require [43]; this tendency is not specific to South Korea [11, 18, 44]. Economic status in particular is a major factor determining the use of medical services [45], and several countries have proposed multiple policies to address financial barriers in an effort to ensure the use of essential medical services [46–49]. In South Korea, financial barriers to healthcare remain despite the country’s universal health insurance system [50, 51]. Notably, however, prior findings have led to the implementation of improved policies that focus on access, which resulted in an expansion of the coverage of the NHI in South Korea, consequently reducing the costs of medical services for people with low socioeconomic status [52–55].

Addressing need factors, pain, poor subjective health status, and depression because they are key determinants of unmet healthcare needs

Our findings show that the lowest subjective health status and high levels of stress, pain, and depression are significantly associated with unmet healthcare needs. These results are consistent with those of the previous studies; that is, poor subjective health status [56], increases pain [57], and high stress and depression [58, 59] cause more unmet healthcare needs. In particular, participants with poor subjective health status were in serious need of medical services. Therefore, acceptability-related reasons for unmet healthcare needs may have a strong influence on such individuals’ access to medical services [21]. Moreover, severe depression may have a significant impact on access-related reasons for unmet healthcare needs, as depression can lead to poor health behavior [60] and financial burdens [61, 62]. Further, the associations between obesity and low accessibility were discovered: they were found to be related to the physical restrictions owing to obesity-associated pain and physical discomfort. A previous study on the association between obesity and unmet healthcare needs reported that obese older adults are more likely to experience unmet physical activity [63].

Based on these results and those of previous studies, women who are young, have no or a low level of education, are unemployed or employed in blue-collar jobs, and who are severely depressed are more vulnerable and more likely to have unmet healthcare needs as compared to their counterparts. Thus, less-privileged populations with low socioeconomic status require more medical attention and experience diverse health problems [64].

This study had some limitations. First, self-report data were used to measure unmet healthcare needs; therefore, the overall reliability of the data may be questionable [65]. Additionally, the association between various factors and unmet healthcare needs may have been under- or over-reported. However, this would not restrict the generalization of the results; previous studies have suggested that self-reported evaluation of unmet healthcare needs is an appropriate method of analyzing population-level national surveys [5]. Second, the KNHANES provides secondary data, which limited our ability to conduct a detailed analysis of the risk factors. The types of medical institutes (e.g., hospitals and clinics), the specific diseases, the regions, and types of services for which patients encountered unmet healthcare needs should be further analyzed [23]. Finally, we analyzed five-year data, from 2013 to 2017. A cross-sectional study design was used instead of a longitudinal study design, as each individual participated only once in the survey over the five-year period. Therefore, our results, which reflect individual trends, should be supplemented by accumulated longitudinal data [50].

Despite these limitations, our research is significant because it provides up-to-date information concerning unmet healthcare needs, utilizing the KNHANES 2017—the latest reliable data for South Korea. One particular strength of this study lies in the classification of the causes of unmet healthcare needs. Unmet healthcare needs are widely used indicators for evaluating a country’s healthcare system. Therefore, our findings may be a good reference for countries that have similar healthcare systems to that of South Korea, such as France, Germany, Japan, and Ireland, where public and private insurance systems share the burden of medical expenses [66].

Conclusions

Although South Korea has witnessed a steady decrease in unmet healthcare needs, we found that 9.5% of the participants continue to experience these barriers to adequate healthcare. Women with low socioeconomic status experienced the highest level of unmet healthcare needs. Therefore, we recommend the implementation of policies that reduce unmet healthcare needs by enhancing the healthcare system at the national-level and targeting specific groups.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Percentage of population reporting unmet healthcare needs by year.

Additional file 2: Trend of population reporting unmet healthcare needs by year.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dongsu Kim, a professor from the Dongshin University, who reviewed the overall content of this paper. He is a traditional Korean medical doctor and a specialist in the field of traditional Korean medicine policy.

Abbreviations

- CHS

Community Health Survey

- CI

Confidence interval

- KCDC

Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- KNHANES

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- OR

Odds ratio

- SE

Standard error

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.; methodology, B.J.; software, B.J.; validation, I.H.H; formal analysis, B.J.; investigation, I.H.H.; resources, I.H.H.; data curation, B.J. and I.H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.; writing—review and editing, B.J. and I.H.H; supervision, I.H.H. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Availability of data and materials

All original data are publicly available free of charge from the KNHANES website (http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr) for the purposes of academic research.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine in Seoul, South Korea (no. 2019-08-001).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rice N, Smith PC. Ethics and geographical equity in healthcare. J Med Ethics. 2001;27(4):256–261. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.4.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulliford M. Equity and access to healthcare. Access healthcare. 2003;36–60.

- 3.Liu GG, Zhao Z, Cai R, Yamada T, Yamada T. Equity in healthcare access to: assessing the urban health insurance reform in China. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(10):1779–1794. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhardt U, Cheng T. The world health report 2000-Health systems: improving performance. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(8):1064. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allin S, Grignon M, Le Grand J. Subjective unmet need and utilization of healthcare services in Canada: what are the equity implications? Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang J, Guilcher SJ, McIsaac KE, Matheson FI, Glazier R, O’Campo P. An examination of perceived health care availability and unmet healthcare need in the City of Toronto, Ontario. Canada C J Public Health. 2017;108(1):e7–e13. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith S, Connolly S. Re-thinking unmet need for healthcare: introducing a dynamic perspective. Health Econ Policy Law. 2019;1–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sandman L, Hofmann B. Why we don’t need “Unmet Needs”! on the concepts of unmet need and severity in health-care priority setting. Healthc Anal. 2019;27(1):26–44. doi: 10.1007/s10728-018-0361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Communities SOotE. Self-reported unmet needs for medical examination by sex, age, main reason declared and income quintile Statistical Office of the European Communities; 2019 [updated July 16 2019. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=hlth_silc_08. Accessed 16 Aug 2019.

- 10.Kim HJ, Jang J, Park EC, Jang SI. Unmet healthcare needs status and trend of Korea in 2017. Health Policy Manag. 2019;29(1):82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Kim TH, Park EC, Cho WH. Factors influencing unmet need for healthcare services in Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP2555–NP2569. doi: 10.1177/1010539513490789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeon CH, Kwak JW, Kwak MH, Kim JH, Park YS. Factors associated with unmet healthcare needs of the older Korean population: the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017. Korean J Health Promot. 2019;19(2):84–90. doi: 10.15384/kjhp.2019.19.2.84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha R, Jung-Choi K, Kim CY. Employment status and self-reported unmet healthcare needs among South Korean employees. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2019;16(1):9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn Y, Kim N, Kim CB, Ham OK. Factors affecting unmet healthcare needs of older people in Korea. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):510–519. doi: 10.1111/inr.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YS, Lee J, Moon Y, Kim KJ, Lee K, Choi J, et al. Unmet healthcare needs of elderly people in Korea. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0786-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huh S, Kim S. Unmet needs for healthcare among Korean adults: differences across age groups. Korean J Health Econ Policy. 2007;13(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim C, Park MS, Kim EM. Married immigrant women's utilization of healthcare and needs of health services. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2011;22(3):333–341. doi: 10.12799/jkachn.2011.22.3.333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SY, Kim CW, Kang JH, Seo NK. Unmet healthcare needs depending on employment status. Health Policy. 2015;119(7):899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han KT, Park EC, Kim SJ. Unmet healthcare needs and community health center utilization among the low-income population based on a nationwide community health survey. Health Policy. 2016;120(6):630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang B, Chun SM, Park JH, Shin HI. Unmet healthcare needs in people with disabilities: comparison with the general population in Korea. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35(5):627. doi: 10.5535/arm.2011.35.5.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahendran M, Speechley KN, Widjaja E. Systematic review of unmet healthcare needs in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;75:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Hou F. Unmet needs for healthcare. Health Rep. 2002;13(2):23–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibley LM, Glazier RH. Reasons for self-reported unmet healthcare needs in Canada: a population-based provincial comparison. Health Policy. 2009;5(1):87–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Lengerke T, Gohl D, Babitsch B. Re-revisiting the behavioral model of healthcare utilization by andersen: a review on theoretical advances and perspectives. Healthcare utilization in Germany. Springer 2014:11–28.

- 25.Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavalieri M. Geographical variation of unmet medical needs in Italy: a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong E, Ahn BC. Income-related health inequalities across regions in Korea. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JY, Yun J. What else is needed in the Korean government’s master plan for people with developmental disabilities? J Prev Med Public Health. 2019;52(3):200. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.18.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heo J, Oh J, Kim J, Lee M, Lee JS, Kwon S, et al. Poverty in the midst of plenty: unmet needs and distribution of healthcare resources in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e51004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon HJ, Jang SI. Unmet healthcare needs status and trend of Korea in 2015. Health Policy Manag. 2017;27(1):80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin SS. Election pledge and policy tasks of president Moon Jae-in in healthcare sector. Health Policy Manag. 2017;27(2):97. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Papadopoulos A, Tountas Y, Niakas D. Investigating unmet health needs in primary healthcare services in a representative sample of the Greek population. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2013;10(5):2017–2027. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10052017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen SM. Gender differences in spousal caregiving and unmet need for care. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):S187–S195. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.S187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi SH, Cho YT. Sex differentials in the utilization of medical services by marital status. Korea J Popul Stud. 2006;29(2):143–166. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojeda VD, Bergstresser SM. Gender, race-ethnicity, and psychosocial barriers to mental healthcare: an examination of perceptions and attitudes among adults reporting unmet need. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(3):317–334. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derose KP, Varda DM. Social capital and healthcare access: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(3):272–306. doi: 10.1177/1077558708330428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, Yano EM. Access to care for women veterans: delayed healthcare and unmet need. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(Suppl 2):655–661. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson CH, Park J. The nature and correlates of unmet healthcare needs in Ontario, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(9):2291–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall EG. Do young adults have unmet healthcare needs? J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(5):490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hargreaves DS, Elliott MN, Viner RM, Richmond TK, Schuster MA. Unmet healthcare need in US adolescents and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):513–520. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moret L, Nguyen JM, Volteau C, Falissard B, Lombrail P, Gasquet I. Evidence of a non-linear influence of patient age on satisfaction with hospital care. Int J Qual Healthcare. 2007;19(6):382–389. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baiden P, Den Dunnen W, Arku G, Mkandawire P. The role of sense of community belonging on unmet healthcare needs in Ontario, Canada: findings from the 2012 Canadian community health survey. J Public Health. 2014;22(5):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10389-014-0635-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Looper M, Lafortune G. Measuring disparities in health status and in access and use of healthcare in OECD countries. 2009

- 44.Hwang J. Understanding reasons for unmet healthcare needs in Korea: what are health policy implications? BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):557. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3369-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu JF, Leung GM, Kwon S, Tin KY, Van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O. Horizontal equity in healthcare utilization evidence from three high-income Asian economies. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(1):199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D. The attack on universal health coverage in Europe: recession, austerity and unmet needs. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(3):364–365. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elstad JI. Income inequality and foregone medical care in Europe during the great recession: multilevel analyses of EU-SILC surveys 2008–2013. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0389-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1300–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baert K, De Norre B. Perception of Health and Access to Healthcare in the EU-25 in. Eurostat Stat Focus. 2007;2009:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko H. Unmet healthcare needs and health status: panel evidence from Korea. Health Policy. 2016;120(6):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim S, Huh S. Financial burden of healthcare expenditures and unmet needs by socioeconomic status. Korean J Health Econ Policy. 2011;17(1):47–70. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong HS. Korea’s National Health Insurance—lessons from the past three decades. Health Aff. 2011;30(1):136–144. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S, Kwon S. Has the National Health Insurance improved the inequality in the use of tertiary-care hospitals in Korea? Health Policy. 2014;118(3):377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park JM. Equity in the utilization of physician and inpatient hospital services: evidence from Korean health panel survey. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0452-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim S, Kwon S. The effect of extension of benefit coverage for cancer patients on healthcare utilization across different income groups in South Korea. Int J Healthcare Fi. 2014;14(2):161–177. doi: 10.1007/s10754-014-9144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J. The impact of health care coverage on changes in self-rated health: comparison between the near poor and the upper middle class. Health Policy Manag. 2016;26(4):390–398. doi: 10.4332/KJHPA.2016.26.4.390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kress HG. Unmet needs in drug treatment of chronic severe pain–clinical evidence on current and future concepts. Eur J Pain Supp. 2009;3(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/S1754-3207(09)70004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eun H, Park EC, Oh DH, Cho E. The effect of stress and depression on unmet medical needs. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2017;27(1):44–54. doi: 10.24304/kjcp.2017.27.1.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Starkes JM, Poulin CC, Kisely SR. Unmet need for the treatment of depression in Atlantic Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(10):580–590. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rafael B, Konkolÿ BT, Kovács P. Anxiety, depression, health-related control beliefs, and their association with health behavior in patients with ischemic heart disease. Orv Hetil. 2015;156(20):813–822. doi: 10.1556/650.2015.30158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leone T, Coast E, Narayanan S, de Graft Aikins A. Diabetes and depression comorbidity and socio-economic status in low and middle income countries (LMICs): a mapping of the evidence. Global Health. 2012;8(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Angstman KB, Doganer YC, DeJesus RS, Rohrer JE. Increased medical cost metrics for patients 50 years of age and older in the collaborate care model of treatment for depression. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16(2):102–106. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eronen J, von Bonsdorff MB, Törmäkangas T, Rantakokko M, Portegijs E, Viljanen A, et al. Barriers to outdoor physical activity and unmet physical activity need in older adults. Prev Med. 2014;67:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryant T, Leaver C, Dunn J. Unmet healthcare need, gender, and health inequalities in Canada. Health Policy. 2009;91(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sherbourne CD, Dwight-Johnson M, Klap R. Psychological distress, unmet need, and barriers to mental healthcare for women. Womens Health Issues. 2001;11(3):231–243. doi: 10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tapay N, Colombo F. Private health insurance in OECD countries: the benefits and costs for individuals and health systems. Towards high-performing health systems: policy studies. 2004:265–319.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Percentage of population reporting unmet healthcare needs by year.

Additional file 2: Trend of population reporting unmet healthcare needs by year.

Data Availability Statement

All original data are publicly available free of charge from the KNHANES website (http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr) for the purposes of academic research.