Abstract

Background

While it is understood that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is primarily complicated by respiratory failure, more data are emerging on the cardiovascular complications of this disease. A subset of COVID-19 patients present with ST-elevations on electrocardiogram (ECG) yet normal coronary angiography, a presentation that can fit criteria for myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis (MINOCA). There is little known about non-coronary myocardial injury observed in patients with COVID-19, and we present a case that should encourage further conversation and study of this clinical challenge.

Case summary

An 86-year-old man presented to our institution with acute hypoxic respiratory failure and an ECG showing anteroseptal ST-segment elevation concerning for myocardial infarction. Mechanic ventilation was initiated prior to presentation, and emergent transthoracic echocardiography reported an ejection fraction of 50–55%, with no significant regional wall motion abnormalities. Next, emergent coronary angiography was performed, and no significant coronary artery disease was detected. The patient tested positive for COVID-19. Despite supportive management in the intensive care unit, the patient passed away.

Discussion

We present a case of COVID-19 that is likely associated with MINOCA. It is crucial to understand that in COVID-19 patients with signs of myocardial infarction, not all myocardial injury is due to obstructive coronary artery disease. In the case of COVID-19 pathophysiology, it is important to consider the cardiovascular effects of hypoxic respiratory failure, potential myocarditis, and significant systemic inflammation. Continued surveillance and research on the cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 is essential to further elucidate management and prognosis.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, ST-segment elevation, MINOCA, Case report

Learning points

One of the cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 may include myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis, and it is important to consider hypoxic respiratory failure, myocarditis, and significant systemic inflammation as potential causes for this type of myocardial injury.

COVID-19 and myocardial injury are associated with a higher incidence of ventilator-dependent respiratory failure, and a higher short-term mortality rate compared to those without myocardial injury.

Introduction

As our understanding of COVID-19 evolves, the findings of elevated troponin levels and/or ST-segment elevations raise concern that COVID-19 can induce cardiovascular complications involving the coronary arteries.1–4 We present a unique case of COVID-19 that is most consistent with MINOCA, myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis.

Timeline

Case presentation

An 86-year-old man with a past medical history significant for dementia and hypertension was transferred to our institution from an outside hospital out of concern for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A week prior to presentation, the patient developed a cough and shortness of breath, with no chest pain reported. He presented to an outside institution with acute hypoxic respiratory failure, and mechanical ventilation was initiated prior to transfer to our institution.

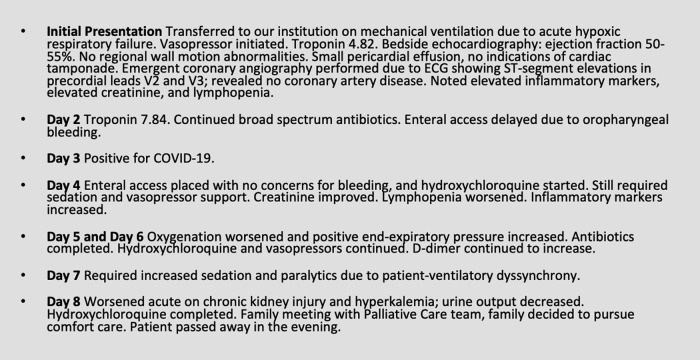

Initial electrocardiography prior to transfer was concerning for anteroseptal ST-segment elevation in precordial leads, and this was confirmed upon presentation to our institution. Physical examination was significant for a blood pressure of 85/57 mmHg, and he was sedated and intubated. A cardiopulmonary exam yielded no abnormalities. Admission labs (as shown in Table 1) were significant for a troponin of 4.82 ng/mL (normal value < 0.10 ng/mL), creatinine of 1.84 mg/dL (normal value < 1.25 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase of 496 U/L (normal value 120–250 U/L), and a C-reactive protein of 173 mg/L (normal value < 5 mg/L). Chest radiography reported bilateral infiltrates at the bases with no other abnormalities. Electrocardiography revealed 3–4 mm ST-segment elevations in leads V2 and V3 as seen in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Trend of biomarkers during hospitalization; HD = Hospital Day

| Lab value (reference range) | HD #1 | HD #2 | HD #3 | HD #4 | HD #5 | HD #6 | HD #7 | HD #8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (4–12 K/µL) | 4.5 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 7.1 | 12.1 | 21 |

| Absolute lymphocytes (1.5–3.2 K/µL) | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.1 | |

| Haemoglobin (14.0–18.0 g/dL) | 12.6 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.3 |

| Platelets (140–400 K/µL) | 161 | 142 | 111 | 95 | 93 | 90 | 112 | 166 |

| Creatinine (<1.25 mg/dL) | 1.84 | 1.51 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 1.35 | 2.20 | 3.9 |

| Troponin (<0.10 ng/mL) | 4.82 | 7.84 | ||||||

| Creatine kinase (30–200 U/L) | 993 | 536 | 483 | |||||

| D-dimer (<230 ng/mL) | 248 | 454 | 687 | 1163 | 1699 | 2641 | ||

| C-reactive protein (<5 mg/L) | 173 | 206 | 194 | 195 | 172 | 171 | 199 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (120–250 U/L) | 496 | 354 | 497 | 530 | 637 | 583 | ||

| Ferritin (22–275 ng/mL) | 2237 | 2602 | 3147 | 2304 | ||||

| Aspartate transaminase (5–34 U/L) | 121 | 111 | 141 | 212 | 255 | 358 | 178 | 153 |

| Alanine transaminase (0–55 U/L) | 35 | 30 | 32 | 55 | 69 | 100 | 68 | 62 |

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram on the patient’s presentation to emergency department. Noted sinus rhythm with first degree AV block, left axis deviation, and ST-segment elevations in leads V2 and V3.

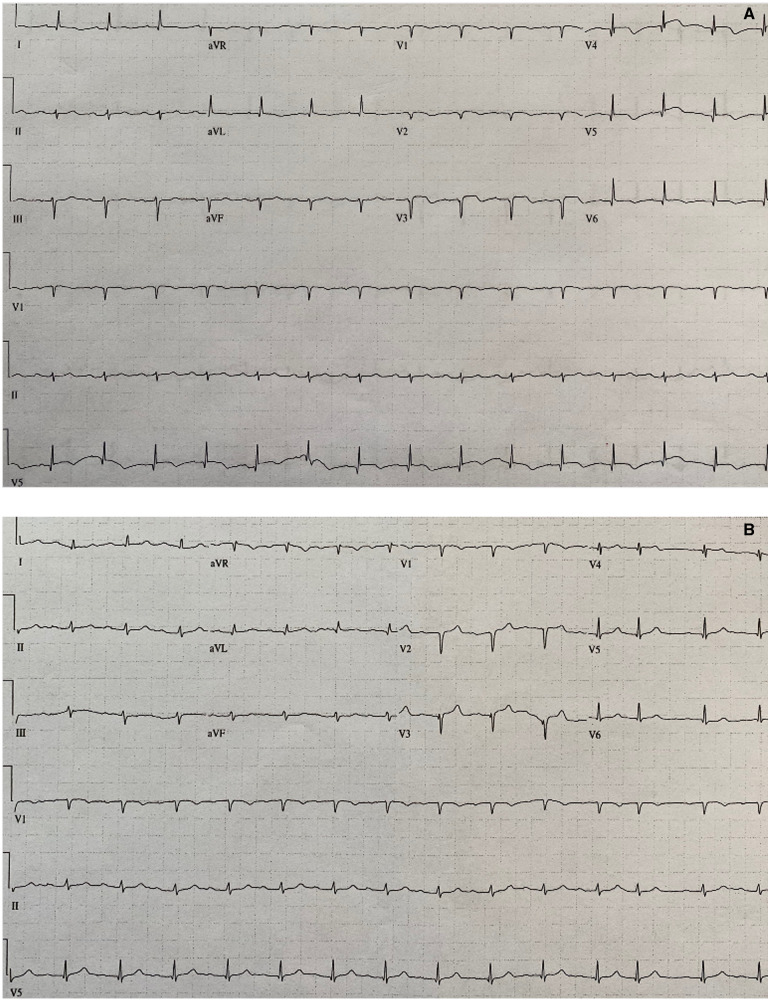

An emergent transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction of 50–55%, no significant regional wall motion abnormalities, and no signs of cardiac tamponade. Emergent coronary angiography immediately followed, and no significant coronary artery disease was detected as seen in Figure 2A,B. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, requiring mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support. The following day, troponin increased to 7.84 ng/mL, likely due to a small amount of myonecrosis.

Figure 2.

(A) Coronary angiography of left coronary artery; no obstruction appreciated. (B) Coronary angiography of right coronary artery; no obstruction appreciated.

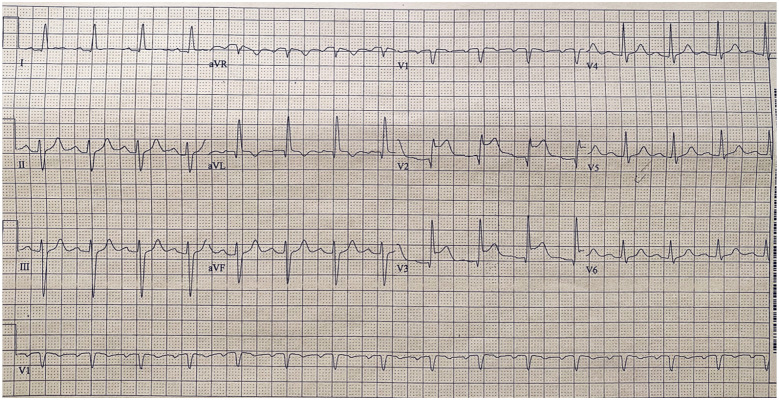

On hospital Day 3, the patient’s COVID-19 test came back positive. By hospital Day 5, his respiratory status worsened and he required increased oxygen and positive end-expiratory pressure. Despite initial improvement with intravenous diuretics, his renal function worsened, as did lymphopenia and inflammatory biomarker abnormalities. On hospital Day 7, he required higher amounts of oxygenation. As seen in Figure 3A,B, his subsequent electrocardiograms showed a loss of R waves, transient T wave inversions, and deepened Q waves. On hospital Day 8, amidst worsening kidney injury and a further rise in the D-dimer level, the patient’s family decided to pursue comfort care measures and, on the same day, the patient died.

Figure 3.

(A) Electrocardiogram on hospital Day 2, about 24 h after admission electrocardiogram. Compared to admission electrocardiogram, leads V2 and V3 show loss of R wave, deepened Q waves, ST-segment flattening, and T wave inversions. (B) Electrocardiogram on hospital Day 7. Overall, QRS voltage has slightly decreased. In leads V2 and V3, T wave inversions are no longer present, but the Q waves have deepened.

Discussion

Historically, coronaviruses have been shown to affect the cardiovascular system, and the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is no exception. SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor for host cell entry,5 and pathology involving the ACE2 receptor can result in cardiac dysfunction and heart failure.6 It is not yet fully understood why some patients with COVID-19 have signs of myocardial infarction in the absence of coronary obstruction.1,6,7

Myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary atherosclerosis is defined by evidence of acute myocardial infarction with no major luminal irregularities seen on coronary angiography (no lesions obstructing coronary artery diameter by more than 50%).8 Our patient’s elevated cardiac troponin values, new ischaemic electrocardiogram changes, and normal coronary angiography are consistent with this clinical syndrome. Pathophysiological mechanisms that can cause MINOCA include plaque rupture, coronary artery spasm, spontaneous coronary dissection, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, coronary thromboembolism, myocarditis, and type-2 acute myocardial infarction. The authors feel that the patient’s presentation is most consistent with MINOCA due to type-2 acute myocardial infarction or focal myocarditis. A type-2 acute myocardial infarction can result from severe coronary oxygen supply–demand mismatch, which may have certainly been the case with our patient given his hypoxic respiratory failure and septic shock. Clinically suspected myocarditis in COVID-19, without evidence of endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) or cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), is debateable.9,10 Most reports of myocarditis due to COVID-19 result in a decrease in left ventricular systolic function,9,11 which is not present in our patient. Further, a recent commentary by Peretto et al.12 states that in the setting of COVID-19 infection, the term ‘myocarditis’ should only refer to a diagnosis proven by EMB or autopsy. On the other hand, cases of COVID-19 myocarditis supported by magnetic resonance imaging have been reported in the setting of normal left ventricular systolic function,13,14 and there is growing evidence of myocardial inflammation seen on EMB.5,15 To what degree this inflammation involves the cardiac interstitium vs the cardiac myocytes is still be elucidated,4,15,16 and further pathological studies are needed to determine if COVID-19 is truly a cardiotropic virus.

Coronary angiography revealed no sign of potentially obstructive stenosis, and the patient’s clinical presentation did not match the typical clinical picture of plaque rupture, coronary artery spasm, or dissection. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is less likely since there were no echocardiographic signs of apical ballooning. The possibility of underlying thromboembolism in our patient is unlikely, as he had no thrombophilia disorder and did not have the risk factors typically associated with coronary artery embolism.8

It is important to discuss the theme of cytokine storm seen in critically ill patients with COVID-19, as cytokines and systemic inflammation may cause plaque rupture or myocardial inflammation.2,3 Our patient’s elevated biomarkers support underlying systemic inflammation. One particular biomarker, D-dimer, can signify a pro-thrombotic state, cytokine secretion, and systemic inflammation.17 Our patient initially presented with a D-dimer level of 248 ng/mL (normal <230 ng/mL), but it did eventually rise as high as 2641 ng/mL. Our patient’s biomarker levels on presentation do not necessarily support the mechanisms of microthrombi or a high inflammatory burden alone causing ST-segment elevation. Overall, more research is needed to learn if and how type-2 acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and cytokine storm play a role in COVID-19 infection presenting as MINOCA.

With regards to the management of the patient, our patient presented very early in our institution’s COVID-19 surge, and there was not yet any process in place limiting procedures such as coronary angiography. It is understood that his functional status was less than ideal. However, his presentation prompted coronary angiography as the next step, and this was based on our institution’s standard of care at that time. The monitoring leads during angiography did not include the precordial leads, so it was not possible to determine if ST-segment elevation was present during the procedure. A cardiac B type natriuretic peptide level and tests for common cardiotropic infectious agents were not checked, which would help with confirming the diagnosis. There were no findings on angiography or echocardiography that prompted intracoronary imaging. CMR can be useful in MINOCA, as Dastidar et al.18 revealed that CMR was able to identify a final diagnosis in 74% of a large cohort of patients with MINOCA. Unfortunately, the patient’s haemodynamic instability prevented further imaging such as CMR.

Conclusion

Overall, our patient’s presentation is most consistent with MINOCA due to type-2 acute myocardial infarction or focal myocarditis. As we learn more about the underlying pathophysiology of COVID-19 and myocardial injury, bridging this gap is crucial. Patients with coronavirus-associated myocardial involvement have clinical evidence of a higher incidence of ventilator-dependent respiratory failure and higher short-term mortality compared to those without myocardial injury.19

Lead author biography

Casey Meizinger is a third year Internal Medicine resident physician at Abington Jefferson Health in Abington, PA. She was a Division I Student-Athlete at the University of Louisville, where she graduated Summa Cum Laude in Exercise Science. She went on to complete her MD degree with AOA honors at Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia, PA. She is also an American College of Sports Medicine certified personal trainer. She is excited to pursue the next stage of her career, a Cardiovascular Disease fellowship.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing these cases and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The patient reported in this case is deceased. Despite the best efforts of the authors, they have been unable to contact the patient's next-of-kin to obtain consent for publication. Every effort has been made to anonymize the case. This situation has been discussed with the editors.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, Yatskar L, Harari R, Shah B. et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19 – a case series. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2478–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon S, Vardeny O.. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system, a review. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonow R, Fonarow G, O’Gara P, Yancy C.. Association of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A. et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:911–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F.. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J Virol 2020;94:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Gill D, Walker J, Rasekhi R, Bozorgnia B, Amanullah A.. Myocardial injury and COVID-19: possible mechanisms. Life Sci 2020;253:117723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stefanini G, Montorfano M, Trabattoni D, Andreini D, Ferrante G, Ancona M. et al. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19. Circulation 2020;141:2113–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agewall S, Beltrame JF, Reynolds HR, Niessner A, Rosano G, Caforio ALP. et al. ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J 2017;38:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y.. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis treated with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ozieranski K, Tyminska A, Caforio A.. Clinically suspected myocarditis in the course of coronavirus infection. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2118–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D. et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peretto G, Sala S, Caforio A.. Acute myocardial injury, MINOCA, or myocarditis? Improving characterization of coronavirus-associated myocardial involvement. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2124–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Besler M, Arslan H.. Acute myocarditis associated with COVID-19 infection. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doyen D, Moceri P, Ducreux D, Dellamonica J.. Myocarditis in a patient with COVID-19: a cause of raised troponin and ECG changes. The Lancet 2020;395:1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sala S, Peretto G, Gramegna M, Palmisano A, Villatore A, Vignale D. et al. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1861–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou R. Does SARS-CoV-2 cause viral myocarditis in COVID-19 patients? Eur Heart J 2020;41:2123–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDermott M, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Green D, Liu K. et al. Inflammatory markers, D-dimer, pro-thrombotic factors and physical activity levels in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 2004;9:103– 115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dastidar A, Baritussio A, De Garate E, Drobni Z, Biglino G, Signhal P. et al. Prognostic role of CMR and conventional risk factors in myocardial infarction with nonobstructed coronary arteries. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:1973–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F. et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.