Abstract

Objective:

To examine the associations between body-mass index (BMI) at 2–4 years and 5–7 years and age at peak height velocity (APHV), an objective measure of pubertal timing, among boys and girls from predominantly racial minorities in the US that have been historically underrepresented in this research topic.

Study design:

This study included 1,296 mother-child dyads from the Boston Birth Cohort, a predominantly Black and low-income cohort enrolled at birth and followed prospectively during 1998–2018. The exposure was overweight or obesity, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference standards. The outcome was APHV, derived using a mixed effects growth curve model. Multiple regression was used to estimate overweight or obesity-APHV association and control for confounders.

Results:

Obesity at 2–4 years was associated with earlier APHV in boys (B in years, −0.19; 95%CI, −0.35 to −0.03) and girls (B, −0.22; 95%CI, −0.37 to −0.07). Obesity at 5–7 years was associated with earlier APHV in boys (B, −0.18; 95%CI, −0.32 to −0.03), while overweight and obesity at 5–7 years were both associated with earlier APHV in girls (overweight:B,−0.24; 95%CI, −0.40 to −0.08; obesity: B, −0.27; 95%CI, −0.40 to −0.13). With BMI trajectory, boys persistently overweight or obese and girls who were overweight or obese at 5–7 years, irrespective of overweight or obesity status at 2–4 years, had earlier APHV.

Conclusions:

This prospective birth cohort study found that overweight or obesity during 2–7 years was associated with earlier pubertal onset in both boys and girls. The BMI trajectory analyses further suggest that removal of overweight or obesity may halt the progression towards early puberty.

Keywords: obesity, childhood obesity, puberty, puberty onset, epidemiology, racial disparities, health disparities, endocrinology

Early puberty has implications for a range of cardiometabolic health outcomes [1–3], including obesity, heart disease [4], stroke, diabetes [5], and the metabolic syndrome [6–10]; psychosocial and behavioral outcomes [11–13] including substance use [14–17], depression, anxiety, and eating disorders; breast and possibly endometrial, cervical, and testicular cancer [18,19]; and increased all-cause mortality. These associations are hypothesized to relate to a combination of increased body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular risk factors, adverse metabolic imprinting, and programming effects of birthweight [20–23].

There has been a global secular trend toward earlier pubertal onset [24–29] tracking with the childhood obesity epidemic, leading to the hypothesis that the two may be related [30]. Many studies have investigated this hypothesis in girls, but the evidence has been scarce and conflicting in boys, with mostly cross-sectional or retrospective cohort studies that have shown different results [31–39]. Prospective cohort studies showed an inverse relationship between pubertal onset and prepubertal BMI [40–43] but did not adjust for important potential confounders such as maternal obesity and maternal age at menarche.

Among the challenges involved in studying pubertal onset in boys is the lack of an objective, standardized, and easily obtainable measure. Although girls have age at menarche to mark puberty, boys require more burdensome measures such as testicular volume measurement or longitudinal Tanner staging. Age at peak height velocity (APHV), which reflects the timing of the pubertal growth spurt and correlates with the development of secondary sexual characteristics, has been increasingly used [44,45].

Using a well-established prospective birth cohort, the Boston Birth Cohort (BBC), we sought to examine the relationships between overweight and obesity at 2–4 years and 5–7 years, BMI trajectories between these periods, and APHV in both boys and girls. We used age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles and z-scores, which are widely used surrogates for body fat mass and remain relatively stable throughout the pubertal transition [46–48]. We hypothesized that overweight and obesity during the two age intervals would be associated with earlier APHV.

Methods

The BBC is a cohort of predominantly Black, low-income mother-child dyads receiving care at the Boston Medical Center (BMC). The BBC has been described previously [49–51]. Briefly, mothers delivering singleton live births were approached within 1–3 days postpartum and invited to enroll. Exclusion criteria included in-vitro fertilization, multiple gestation pregnancies, major birth defects, and deliveries induced by maternal trauma. The postnatal follow-up included those enrolled children who continued to receive pediatric care at BMC from birth up to 21 years of age. Written consent was obtained from all mothers and from some children depending on their age. Maternal demographic characteristics and medical histories were obtained during a standardized questionnaire interview, and birth and child health outcomes were obtained by reviewing electronic medical records (EMR). All data were de-identified and accessible only to authorized investigators. The BMC and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health institutional review boards approved the study protocol.

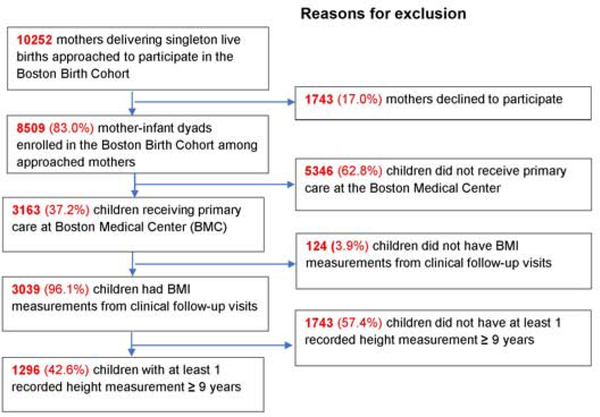

A total of 8,509 mother-child dyads was recruited among 10,252 mothers asked to enroll between 1998 and 2006 (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Of these, 3,163 children continued to receive care at BMC, 3,039 had BMI measurements from well-child visits, and 1,296 had at least 1 recorded height measurement at or greater than 9 years. Compared with the 8,509 dyads originally enrolled, the 1,296 mothers included in this study are more likely to be Black, overweight or obese before pregnancy, and, among mothers of boys only, have pre-existing or gestational diabetes (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 1;

online. Flowchart of study inclusion and exclusion. Percentages are calculated using the number in the immediately previous step as the “total”.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics between total Boston Birth Cohort (BBC) sample and sample included in this study (unimputed data)

| Boys | |||

| Variable | Total BBC sample | Included in this study | P value |

| No. | 4237 | 663 | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (y) | 28.2 ± 6.4 | 28.7 ± 6.7 | 0.072 |

| Race, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 1997 (47.1) | 441 (66.5) | |

| Non-Black | 2240 (52.9) | 222 (33.5) | |

| Education level, No. (%) a | 0.135 | ||

| High school or below | 2680 (64.2) | 441 (67.2) | |

| Some college or above | 1493 (35.8) | 215 (32.8) | |

| Marital Status, No. (%) b | 0.253 | ||

| Married | 1609 (38.8) | 239 (36.4) | |

| Not married | 2541 (61.2) | 417 (63.4) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, mean ± SD (kg/m2) c | 26.0 ± 6.2 | 26.6 ± 6.3 | 0.013 |

| Pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity, No. (%) c | 1876 (47.5) | 337 (53.5) | 0.005 |

| Age at menarche, mean ± SD (y) d | 12.9 ± 1.9 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 0.136 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) e | 456 (10.8) | 89 (13.4) | 0.044 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, No. (%) f | 780 (18.6) | 116(17.6) | 0.568 |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Birthweight, mean ± SD (g) f | 3028 ± 771 | 2992 ± 818 | 0.291 |

| Low birthweight, No. (%) f | 1002 (23.7) | 163 (24.6) | 0.601 |

| Preterm birth, No. (%) | 1173 (27.7) | 180 (27.2) | 0.774 |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD (wk) | 37.9 ± 3.1 | 37.8 ± 3.4 | 0.227 |

| Girls | |||

| Variable | Total BBC sample | Included in this study | P value |

| No. | 4272 | 633 | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (y) | 28.2 ± 6.5 | 28.4 ± 6.9 | 0.376 |

| Race, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 2034 (47.6) | 411 (64.9) | |

| Non-black | 2238 (52.4) | 222(35.1) | |

| Education level, No. (%) h | 0.213 | ||

| High school or below | 2743 (65.7) | 425 (68.2) | |

| Some college or above | 1433 (34.3) | 198 (31.8) | |

| Marital Status, No. (%) i | 0.390 | ||

| Married | 1511 (36.1) | 214 (34.3) | |

| Not married | 2679 (63.9) | 410 (65.7) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, mean ± SD (kg/m2) j | 26.0 ± 6.2 | 26.6 ± 6.3 | 0.013 |

| Overweight or obesity, No. (%) j | 1887 (47.4) | 325 (54.2) | 0.002 |

| Age at menarche, mean ± SD (y) k | 12.9 ± 1.9 | 12.9 ± 2.1 | 0.602 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) l | 427 (10.0) | 62 (9.8) | 0.868 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, No. (%) m | 856(20.2) | 106(17.0) | 0.060 |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Birthweight, mean ± SD (g) | 2887 ± 762 | 2836 ± 795 | 0.120 |

| Low birthweight, No. (%) | 1219 (28.5) | 191 (30.2) | 0.395 |

| Preterm birth, No. (%) | 1143(26.8) | 174(27.5) | 0.698 |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD (wk) | 37.9 ± 3.2 | 37.7 ± 3.5 | 0.101 |

Data on baseline characteristics was complete with the exception of following variables labelled with superscripts:

Maternal education level: N=4173 (missing 64) for total sample, N=656 (missing 7) for included sample

Maternal marital status: N=4150 (missing 87) for total sample, N=656 (missing 7) for included sample

Pre-pregnancy BMI: N=3947 (missing 290) for total sample, N=630 (missing 33) for included sample

Age at menarche: N=3335 (missing 902) for total sample, N=647 (missing 16) for included sample

Maternal diabetes: N=4233 (missing 4) for total sample, N=663 (missing 0) for included sample

Smoked during pregnancy: N=4203 (missing 34) for total sample, N=658 (missing 5) for included sample

Birthweight and low birth weight: N=4236 (missing 1) for total sample, N=663 (missing 0) for included sample

Maternal education level: N=4263 (missing 96) for total sample, N=623 (missing 10) for included sample

Maternal marital status: N=4190 (missing 82) for total sample, N=654 (missing 9) for included sample

Pre-pregnancy BMI: N=3983 (missing 289) for total sample, N=600 (missing 33) for included sample

Age at menarche: N=3412 (missing 860) for total sample, N=617 (missing 16) for included sample

Maternal diabetes: N=4267 (missing 5) for total sample, N=633 (missing 0) for included sample

Smoked during pregnancy: N=4238 (missing 34) for total sample, N=624 (missing 9) for included sample

Child weight and height were measured during pediatric clinic visits. BMI percentiles were calculated using reference standards from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [52]. Overweight was defined as BMI ≥85th and <95th percentile for age and sex, obese as BMI ≥95th percentile, and overweight or obesity as BMI ≥85th percentile. Exposures were BMI category at 2–4 years, at 5–7 years, and BMI trajectories, which were categorized into 4 groups: 1) persistently not overweight or obese: not overweight or obese at 2–4 years and 5–7 years; 2) not overweight or obese to overweight or obese: not overweight or obese at 2–4 years and overweight or obese at 5–7 years; 3) overweight or obese to not overweight or obese: overweight or obese at 2–4 years and not overweight or obese at 5–7 years; 4) persistently overweight or obese: overweight or obese at 2–4 years and 5–7 years.

APHV was calculated using the SuperImposition by Translation And Rotation (SITAR) mixed effects growth curve model, a well-validated, flexible model that uses subject-specific random effects to fit individual growth curves to a mean curve and provides unbiased estimates of APHV (sitar package in R) [53–54].

We identified covariates that have been associated with childhood obesity and/or with earlier puberty. Of these, the BBC included data on maternal race (dichotomized as Black versus non-Black due to higher rates of early puberty and obesity among Black children [55–57]), maternal education (high school or below versus college or above, as an indicator of socioeconomic position [58]), marital status (married versus unmarried, as an indicator of household structure [59,60]), maternal age at menarche [61] (divided into terciles), pre-pregnancy BMI [62,63] (not overweight or obese (BMI<25 kg/m2) versus overweight or obesity (BMI≥25 kg/m2)), pre-existing or gestational diabetes [64], smoking during pregnancy [65], preterm birth, and low birthweight. Household income was not included because of the large amount of missing data (>30%).

Missing maternal characteristics and children’s BMI measurements were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) with predictive mean matching (PMM) via mice package in R (R Foundation) [66], using methods described previously [51]. Missing BMI measurements were imputed for the last year of each developmental window – for example, a child missing a BMI measurement between 5–7 years would have BMI imputed at 7 years. 105 (15.8%) boys and 88 girls (13.9%) were missing a BMI measurement between 2–4 years, and 104 boys (15.7%) and 85 (13.4%) girls were missing a BMI measurement between 5–7 years. Other variables that required imputation were: maternal education (1.1% missing data among boys; 1.6% among girls), pre-pregnancy BMI (5.0% among boys; 5.2% among girls), age at menarche (2.4% among boys and girls), and smoking during pregnancy (0.8% among boys; 1.4% among girls).

Characteristics of the four BMI trajectory groups were compared using X2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Crude and adjusted linear regression were performed to examine the following. Associations between BMI categories at 2–4 years, BMI categories at 5–7 years, and APHV, comparing overweight, obese, and overweight or obese to a reference of normal BMI; linear trends between BMI z-scores at 2–4 years, 5–7 years, and APHV; and associations between BMI trajectories and APHV. Interactions between BMI categories at 2–4 years and 5–7 years were also examined using a cross-product term.

Final adjusted models included the following covariates: maternal race, maternal education level, maternal marital status, maternal age at menarche, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal diabetes, smoking status during pregnancy, and child’s preterm birth and low birthweight status. Stratified analyses were performed by each stratum of the covariates, and sensitivity analyses were performed using the unimputed dataset. R software, version 3.5.3 (R Foundation) and SAS (SAS Institute), version 9.4 were used for all analyses. A significance level of two-sided P<0.05 was used.

Results

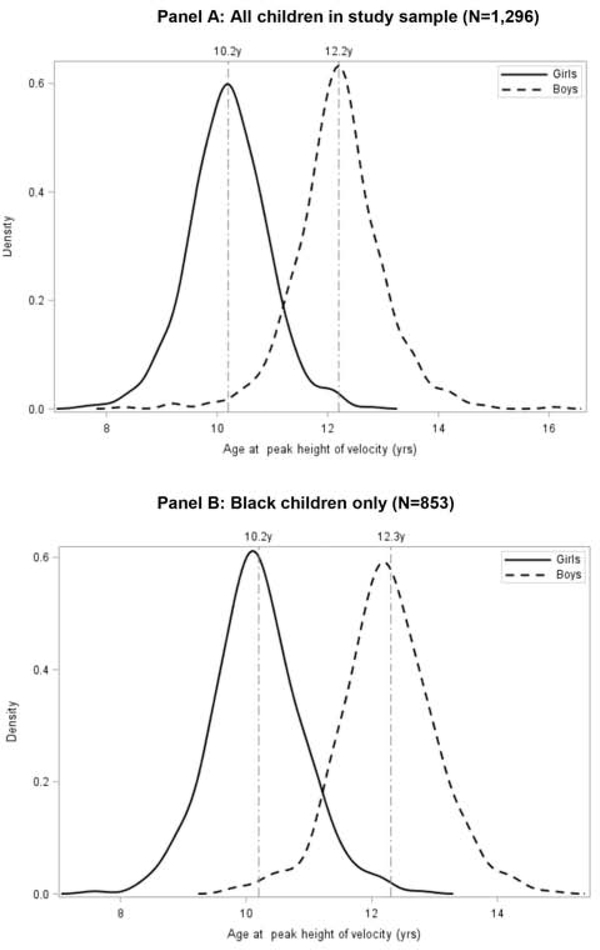

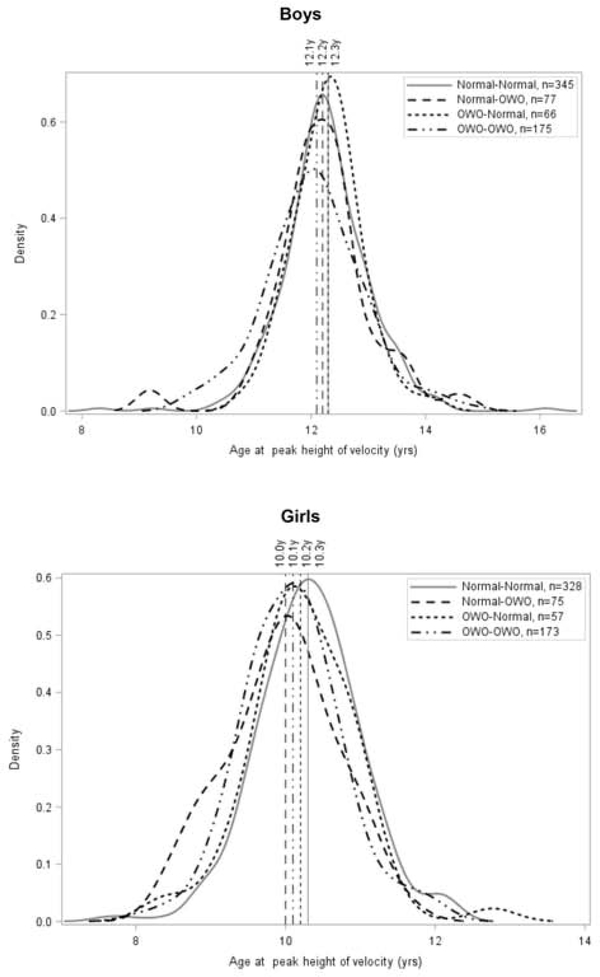

1,296 mother-child dyads (663 boys and 633 girls) were included, of which 853 (63.8%) were Black. Mean APHV was 12.2 years in boys and 10.2 years in girls (P<0.001), and 12.3 years in Black boys and 10.2 years in Black girls (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com). Distributions of BMI trajectory groups were: 345 (50.0%) boys and 328 (51.8%) girls in the persistently not overweight or obese group, 77 (11.6%) boys and 75 (11.9%) girls in the not overweight or obese to the overweight or obese group, 66 (10.0%) boys and 57 (9.0%) girls in the overweight or obese to not overweight or obese group, and 175 (26.4%) boys and 173 (27.3%) girls in the persistently overweight or obese group (Table 2). Obesity prevalence increased from 19.0% at 2–4 years to 25.0% at 5–7 years in boys, and from 18.0% to 24.6% in girls.

Figure 2;

online. Distribution of APHV by sex. Panel A, All children in study sample (N=1,296). Panel B: Black children only (N=853).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 1,296 mother-child pairs by sex and BMI trajectory group (imputed data)

| Boys | ||||||

| Variable / BMI Trajectory Group | Total | Non-OWO to Non-OWO | Non-OWO to OWO | OWO to Non-OWO | OWO to OWO | P value |

| No. (%) | 663 | 345 (50.0) | 77 (11.6) | 66 (10.0) | 175 (26.4) | |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD (y) | 28.7 ± 6.7 | 28.0 ± 6.8 | 31.1 ± 6.5 | 28.5 ± 6.2 | 29.0 ± 6.7 | 0.003 |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.286 | |||||

| Black | 442 (66.5) | 223 (64.6) | 47 (61.0) | 46 (69.7) | 125 (71.4) | |

| Non-black | 223 (33.5) | 122 (35.4) | 30 (39.0) | 20 (30.3) | 50 (28.6) | |

| Education level, No. (%) | 0.627 | |||||

| High school or below | 446 (67.1) | 235 (68.1) | 54 (70.1) | 40 (60.6) | 117 (66.9) | |

| Some college or above | 219 (32.9) | 110 (31.9) | 23 (29.9) | 26 (39.4) | 58 (33.1) | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | 0.375 | |||||

| Married | 226 (34.0) | 117 (33.9) | 30 (39.0) | 22 (33.3) | 72 (41.1) | |

| Not married | 439 (66.0) | 228 (66.1) | 47 (61.0) | 44 (66.7) | 103 (58.9) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI category, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Normal (BMI<25) | 309 (37.5) | 180 (52.2) | 31 (40.3) | 36 (54.6) | 60 (34.3) | |

| Overweight or obese (BMI≥25) | 356 (53.5) | 165 (47.8) | 46 (59.7) | 30 (45.5) | 115 (65.7) | |

| Age at menarche, mean ± SD (y) | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 2.3 | 0.769 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 89 (13.4) | 38 (11.0) | 8 (10.4) | 6 (9.1) | 37 (21.1) | 0.006 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, No.(%) | 118 (17.7) | 58 (16.8) | 19 (24.7) | 11 (16.7) | 30 (17.1) | 0.419 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Low birthweight (<2500g), No. (%) | 163 (24.6) | 93 (27.0) | 23 (29.9) | 16 (24.2) | 31 (17.7) | 0.083 |

| Preterm birth, No. (%) | 180 (27.1) | 91 (26.4) | 32 (41.6) | 24 (36.4) | 33 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| Age at peak height velocity, mean ± SD (y) | 12.2 ± 0.8 | 12.3 ± 0.8 | 12.2 ± 0.9 | 12.3 ± 0.6 | 12.1 ± 0.9 | 0.036 |

| Girls | ||||||

| Variable / BMI Trajectory Group | Total | Non-OWO to Non-OWO | Non-OWO to OWO | OWO to Non-OWO | OWO to OWO | P value |

| No. (%) | 633 | 328 (51.8) | 75 (11.9) | 57 (9.0) | 173 (27.3) | |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD (y) | 28.4 ± 6.9 | 27.8 ± 7.0 | 29.1 ± 6.9 | 28.9 ± 7.1 | 29.1 ± 6.5 | 0.161 |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.208 | |||||

| Black | 411 (64.9) | 204 (62.2) | 54 (72.0) | 34 (59.7) | 119 (68.8) | |

| Non-black | 222 (35.1) | 124 (37.8) | 21 (28.0) | 23 (40.3) | 154 (31.2) | |

| Education level, No. (%) | 0.506 | |||||

| High school or below | 433 (68.4) | 217 (66.2) | 55 (73.3) | 42 (73.) | 118 (68.2) | |

| Some college or above | 200 (31.6) | 111 (33.8) | 20 (26.7) | 15 (26.3) | 55 (31.8) | |

| Marital status, No.(%) | 0.254 | |||||

| Married | 203 (32.1) | 103 (31.4) | 25 (33.3) | 22 (38.6) | 69 (39.9) | |

| Not married | 430 (67.9) | 225 (68.6) | 50 (66.7) | 35 (61.4) | 104 (60.1) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI category, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Normal (BMI<25) | 293 (46.3) | 183 (55.8) | 34 (45.3) | 25 (43.9) | 52 (30.1) | |

| Overweight or obese (BMI≥25) | 340 (53.7) | 145 (44.2) | 41 (54.7) | 32 (56.1) | 121 (69.9) | |

| Age at menarche, mean ± SD (y) | 12.9 ± 2.1 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 2.0 | 12.7 ± 2.0 | 0.366 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 62 (9.8) | 24 (7.3) | 5 (6.7) | 6 (10.5) | 27 (15.6) | 0.021 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, No. (%) | 107 (16.9) | 56 (17.1) | 18 (24.0) | 12 (21.1) | 23 (13.3) | 0.181 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Low birthweight (<2500g), No. (%) | 190 (30.0) | 120 (36.6) | 19 (25.3) | 12 (21.1) | 40 (23.1) | 0.004 |

| Preterm birth, No. (%) | 174 (27.5) | 100 (30.5) | 16 (21.3) | 16 (28.1) | 42 (24.3) | 0.283 |

| Age at peak height velocity, mean ± SD (y) | 10.2 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 0.7 | 10.0 ± 0.7 | 10.2 ± 0.7 | 10.1 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

Table 2 presents univariate comparisons of the characteristics of the BMI trajectory groups by sex. Compared with counterparts with normal BMIs, boys who were overweight or obese at 5–7 years were more likely to be born to mothers with pre-pregnancy BMI≥25 (65.7% among persistently overweight or obese and 59.7% among not overweight or obese to overweight or obese, compared with 47.8% among persistently not overweight or obese and 45.5% among overweight or obese to not overweight or obese, P<0.001) and diabetes (21.1% and 11.0% vs. 10.4% and 9.1%, respectively, P=0.006). Boys who were persistently overweight or obese were least likely to be preterm (18.9% compared with 26.4% among persistently not overweight or obese, 41.6% among not overweight or obese to overweight or obese, and 36.4% among overweight or obese to not overweight or obese groups, P<0.001). Girls persistently overweight or obese were more likely to have mothers with pre-pregnancy BMI≥25 (69.9 %, P<0.001) and diabetes (15.6%, P=0.021) compared with girls in other BMI trajectory groups.

As shown in Table 3, obesity at 2–4 years was associated with significantly earlier APHV in boys (adjusted B, −0.19 year; 95% CI, −0.35 to −0.03) and girls (B, −0.22; 95% CI, −0.37 to −0.07) after adjusting for pertinent covariates. Overweight at 2–4 years was also associated with earlier APHV, but this was not statistically significant with either sex. Tests for linear trend showed an inverse relationship between BMI z-score at 2–4 years and APHV that was significant in girls (P<0.001) but not in boys (P=0.161) (Table 3 and Table 4 [available at www.jpeds.com]).

Table 3.

Associations between APHV and BMI category at 2–4 yrs, BMI category at 5–7 yrs, and BMI trajectories from 2–4 yrs to 5–7 yrs (imputed data)

| BMI Category in Ages 2–4 Years | Males (N=663) | Females (N=633) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Crude | Adjusted | N | Crude | Adjusted | ||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||||

| <85th |  |

422 | REF | REF | 403 | REF | REF |

| 85th–94th |  |

115 | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.11) | −0.07 (−0.23, 0.09) | 116 | −0.06 (−0.21, 0.08) | −0.07 (−0.21, 0.08) |

| ≥95th |  |

126 | −0.19 (−0.35, −0.04)* | −0.19 (−0.35, −0.03)* | 114 | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.07)† | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.07)† |

| P for trenda | 0.099 | 0.161 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| <85th |  |

422 | REF | REF | 403 | REF | REF |

| ≥85th |  |

241 | −0.13 (−0.25, 0.00)* | −0.13 (−0.26, −0.01)* | 230 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.02)* | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.01)* |

| BMI Category in Ages 5–7 Years | |||||||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||||

|

<85th | 411 | REF | REF | 385 | REF | REF |

|

85th–94th | 86 | −0.12 (−0.31, 0.06) | −0.15 (−0.33, 0.03) | 92 | −0.24 (−0.40, −0.08)† | −0.24 (−0.40, −0.08)† |

|

≥95th | 166 | −0.19 (−0.33, −0.04)* | −0.18 (−0.32, −0.03)* | 156 | −0.28 (−0.41, −0.15)§ | −0.27 (−0.40, −0.13)§ |

| P for trenda | 0.034 | 0.041 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

|

<85th | 411 | REF | REF | 385 | REF | REF |

|

≥85th | 252 | −0.17 (−0.29, −0.04)† | −0.17 (−0.29, −0.04)† | 248 | −0.26 (−0.37, −0.15)§ | −0.25 (−0.36, −0.14)§ |

| BMI Trajectories | |||||||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||||

| <85th | <85th | 345 | REF | REF | 328 | REF | REF |

| <85th | ≥85th | 77 | −0.07 (−0.26, 0.13) | −0.07 (−0.27, 0.12) | 75 | −0.36(−0.54, −0.19)§ | −0.35(−0.52, −0.18)§ |

| ≥85th | <85th | 66 | 0.02 (−0.18, 0.23) | 0.01 (−0.20, 0.22) | 57 | −0.09 (−0.29, 0.10) | −0.11 (−0.31, 0.08) |

| ≥85th | ≥85th | 175 | −0.20 (−0.35, −0.06)† | −0.21 (−0.36, −0.07)† | 173 | −0.23 (−0.36, −0.10)§ | −0.23 (−0.36, −0.10)§ |

| P for interactionb | 0.286 | 0.338 | 0.109 | 0.091 | |||

Associations presented as β (95%CI). Adjusted βs are adjusted for maternal race, maternal education level, maternal marital status, smoking during pregnancy, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, maternal age at menarche, maternal diabetes, low birthweight status, and preterm birth status.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

P values for trend are based on linear regression models using BMI z-scores as a continuous variable

P values for interaction are based on models including an interaction term between BMI category at 2–4 years and BMI category at 5–7 years.

Table 4.

Associations between BMI z-scores at ages 2–4 years and 5–7 years and age at peak height velocity (APHV) (imputed data)

| Crude | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | se | P value | R2 | β | se | P value | Partial R2 | |

| Boys | ||||||||

| 2–4 y | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.099 | 0.003 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.161 | 0.002 |

| 5–7 y | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.034 | 0.005 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.041 | 0.005 |

| Girls | ||||||||

| 2–4 y | −0.08 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.021 |

| 5–7 y | −0.12 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.04 | −0.12 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.039 |

Adjusted βs are adjusted for maternal race, maternal education level, maternal marital status, smoking during pregnancy, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, maternal age at menarche, maternal diabetes, low birthweight status, and preterm birth status.

Obesity at 5–7 years was associated with significantly earlier APHV in boys (adjusted B, −0.18 year; 95% CI, −0.32 to −0.03), and both overweight (B, −0.24 year; 95% CI, −0.40 to −0.08) and obesity (B, −0.27 year; 95% CI, −0.40 to −0.13) at 5–7 years were associated with significantly earlier APHV in girls. Tests for linear trend found an inverse relationship between APHV and BMI z-scores at 5–7 years in both boys (P=0.041) and girls (P<0.001).

Figure 3 depicts how APHV varied with BMI trajectory, which was confirmed in regression models. Compared with boys who were persistently not overweight or obese from 2–4 years to 5–7 years, boys who were persistently overweight or obese had significantly earlier APHV (B, −0.21 year; 95% CI, −0.36 to −0.07). Girls, on the other hand, had earlier APHV regardless of whether they were persistently overweight or obese (B, −0.23 year; 95% CI, −0.36 to −0.10), or had normal BMIs at 2–4 years and became overweight or obese at 5–7 years (B, −0.35 year; 95% CI, −0.52 to −0.18) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of APHV by BMI trajectory among boys and girls

Sensitivity analysis of the associations between BMI categories and APHV, and between BMI trajectories and APHV, found similar results using the unimputed dataset (Table 6; available at www.jpeds.com). Overweight or obesity at 2–4 years and at 5–7 years were both associated with earlier APHV in boys and girls, and persistent overweight or obesity was associated with earlier APHV in boys, and girls who were overweight or obese at 5–7 years had earlier APHV regardless of BMI at 2–4 years.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of associations between BMI categories and APHV and BMI trajectories and APHV (unimputed data)

| BMI Percentiles | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | Males (N=558) | Females (N=545) | ||

| <85th |  |

REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 85th–94th |  |

−0.06 (−0.24, 0.12) | −0.07 (−0.27, 0.12) | −0.06 (−0.22, 0.10) | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.13) |

| ≥95th |  |

−0.22 (−0.39, −0.05)* | −0.22 (−0.39, −0.04)* | −0.22(−0.37, −0.06)† | −0.21(−0.38, −0.04)* |

| P for trend a | 0.075 | 0.114 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| <85th |  |

REF | REF | REF | REF |

| ≥85th |  |

−0.15 (−0.29, −0.01)* | −0.15 (−0.30, −0.01)* | −0.14(−0.27, −0.02)* | −0.12(−0.26, 0.01) |

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | Males (N=559) | Females (N=548) | ||

|

<85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

|

85th–94th | −0.17 (−0.36, 0.02) | −0.23 (−0.43, −0.03)* | −0.28(−0.45, −0.12) † | −0.30(−0.48, −0.12) † |

|

≥95th | −0.23 (−0.38, −0.08)† | −0.22 (−0.38, −0.06) † | −0.32(−0.46, −0.18)§ | −0.32(−0.47, −0.17)§ |

| P for trend a | 0.018 | 0.046 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

<85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

|

≥85th | −0.21 (−0.34, −0.07) † | −0.22 (−0.36, −0.08)† | −0.31(−0.43, −0.19)§ | −0.31(−0.44, −0.18)§ |

| BMI Trajectories | Males (N=520) | Females (N=514) | |||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||

| <85th | <85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| <85th | ≥85th | −0.09 (−0.34, 0.15) | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.10) | −0.41(−0.61, −0.22)§ | −0.45(−0.66, −0.24)§ |

| ≥85th | <85th | 0.05 (−0.23, 0.34) | 0.03 (−0.26, 0.32) | −0.12 (−0.37, 0.12) | −0.17 (−0.42, 0.08) |

| ≥85th | ≥85th | −0.23 (−0.39, −0.07)† | −0.23 (−0.40, −0.07)† | −0.29(−0.43, −0.16)§ | −0.29(−0.45, −0.14)§ |

| P for interaction b | 0.329 | 0.571 | 0.134 | 0.056 | |

Associations presented as β (95%CI). Adjusted βs are adjusted for maternal race, maternal education level, maternal marital status, smoking during pregnancy, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, maternal age at menarche, maternal diabetes, low birthweight status, and preterm birth status.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

P values for trend are based on linear regression models using BMI z-scores as a continuous variable

P values for interaction are based on models including an interaction term between BMI category at 2–4 years and BMI category at 5–7 years.

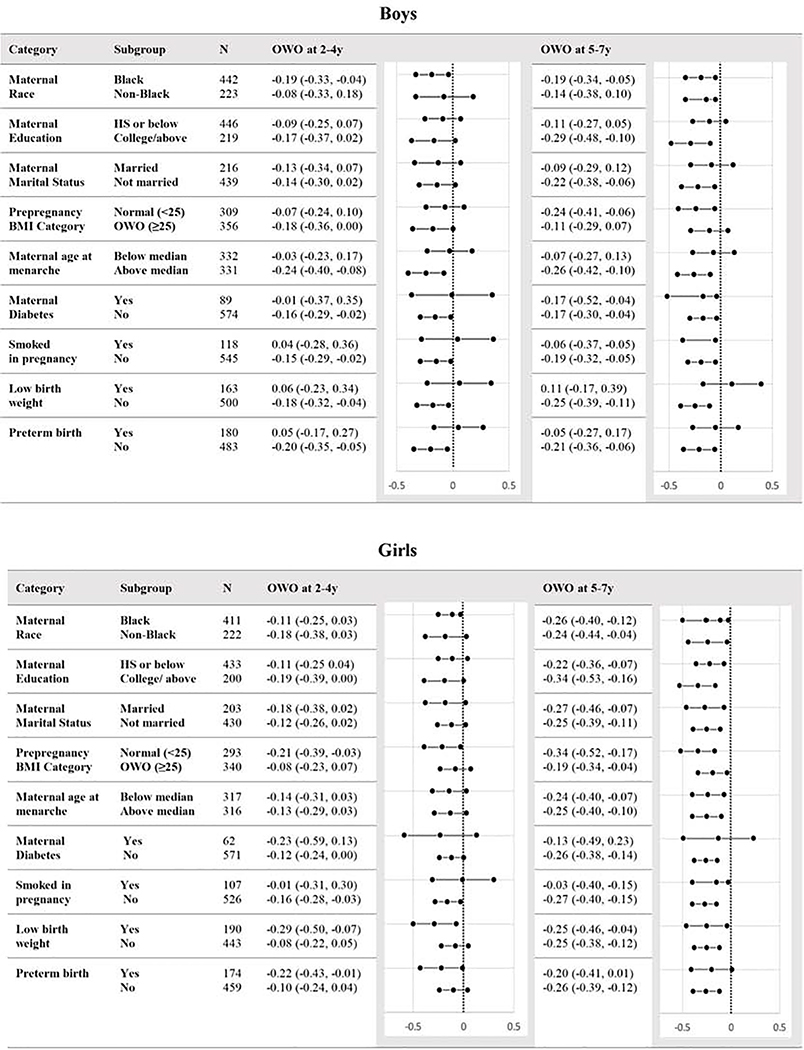

Subgroup analyses revealed negative point estimates across most strata, indicating an inverse relationship between overweight or obese during the two periods and APHV (Figure 4). The only positive point estimates were for boys born with low birthweight, born preterm, or born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy, and none of these relationships were statistically significant. Interestingly, the associations between overweight or obesity and APHV were more often statistically significant among children with non-diabetic mothers (compared with children with diabetic mothers), Black children (compared with non-Black children), children whose mothers were not overweight or obese (compared with children whose mothers were overweight or obese), and non-preterm children (compared with preterm children).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of associations between APHV and overweight or obesityat 2–4y and 5–7y. Associations are presented as βs (95%CI) and adjusted for all other covariates except for the stratified variable.

Discussion

This prospective birth cohort study of predominantly Black mothers and children found significant associations between overweight and obesity at 2–4 years and 5–7 years with earlier APHV in both boys and girls. These associations persisted after controlling for a variety of potential confounders and across strata of pertinent covariates. A dose-response relationship was observed, with higher BMI z-scores associated with earlier APHV. Importantly, associations between APHV and BMI trajectories from 2–4 years to 5–7 years revealed that children with a normal BMI at 5–7 years, regardless of their BMI at 2–4 years, did not experience earlier APHV. The inverse was also true among girls who were overweight or obese at 5–7 years, who experienced earlier APHV regardless of their BMI at 2–4 years. This suggests that the period of time immediately prior to puberty may be most important in triggering early puberty, and that “removing” this obesity exposure period has potential to halt the trend towards earlier puberty. This points to the possibility that interventions promoting a normal weight early in and across the childhood may alter a child’s pubertal development and subsequent health outcomes.

Although previous studies have investigated these relationships, this study is unique in that we controlled for multiple confounders and due to the prospective, longitudinal study design of the cohort, we were able to establish temporality. This study revealed a dose-response relationship by demonstrating the specificity of the exposure-effect relationship. For example, children in the overweight or obese to not overweight or obese group, who had the obesity exposure “removed”, did not experience early APHV unlike their peers who became or remained overweight or obese.

In addition, this study focuses on a predominantly Black, low-income, and urban prospective cohort in the US that includes both boys and girls. Studying the factors that contribute to earlier APHV in this population – which can inform interventions – is important from an equity and policy perspective because children who are racialized as Black, on average, experience more accelerated pubertal development compared with children who are racialized as White. Further, children racialized as Black bear a disproportionate burden of obesity- and cardiometabolic-related health risks and adverse outcomes, which may have lifelong and multigenerational impacts. Although the mechanisms underlying these observed racial differences are not fully understood, research suggests various impacts of structural racism including early life adversity such as stress and material hardship, compromise in the intrauterine environment manifesting as a smaller birth size, rapid growth during infancy, and a lack of access to nutritious foods and spaces for physical activity [55–57].

Moving away from the social construct of race and the repercussions of this construct, the biological mechanisms linking childhood obesity to early APHV implicate multiple factors that work together to activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Notably, leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue, may play a permissive role in pubertal development due to its ability to activate gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility, trigger LH and FSH release from the anterior pituitary, and stimulate enzymes needed to synthesize adrenal androgens [67,68]. Adipose tissue also produces aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogen and promotes puberty in girls (its role in boys remains uncertain). In addition, early weight gain is associated with insulin resistance, which is in turn associated with increased adrenal androgen secretion and compensatory increase in insulin, which results in reduced levels of sex hormone binding globulin, increasing free-sex steroid levels to exert biological effects [69,70].

Another mechanism linking childhood obesity to early APHV is found in the early life origins of disease hypothesis, which postulates that common exposures in utero and during early childhood influence development and health outcomes. As such, the same exposures can promote both childhood obesity and early puberty. One example is smoking during pregnancy, which is associated with increased risk of childhood obesity [71] as well as with early puberty. The early life origins hypothesis suggests that an interaction between maternal metabolic genes and smoking occurs to contribute to childhood obesity, and that in utero exposure to this endocrine disrupter may alter hormone functioning to trigger earlier pubertal development [72]. Another possibility is that epigenetic mechanisms may act to simultaneously increase the risks of childhood obesity and of early APHV.

The prospective and longitudinal nature of this study facilitated the study of specific developmental windows and BMI trajectories. The availability of demographic, clinical, and behavioral data allowed us to draw on more comprehensive models such as the life course model to explain how health disparities may originate from compounding and cumulative effects of exposures during critical stages of development. Because of the richness of the dataset, we were able to control for many confounders and move closer to conditional exchangeability between the exposure groups. Finally, we used a measure of puberty that is standardized, objective, and well-supported by previous studies.

One limitation of this study is that BMI does not differentiate between lean mass and fat mass and may have lower sensitivity than specificity in detecting excess adiposity [73]. Another limitation is that many other confounders were not included, such as nutrition, endocrine disrupting chemicals, genetic variants and epigenetic changes. The influences of these factors on the obesity-puberty associations remain to be examined.

Our results have potential implications for preventative health efforts targeting critical developmental stages, for recognizing impacts of structural disadvantage on pubertal development, and for addressing health inequities by focusing resources on racial minority populations that are often underrepresented in policy and research.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Associations between APHV and BMI category at 2–4 yrs, BMI category at 5–7 yrs, and BMI trajectories from 2–4 yrs to 5–7 yrs after removing children with only one BMI measurement (n=1258) (imputed data)

| BMI Percentile | Males (N=637) | Females (N=621) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | ||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||

| <85th |  |

REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 85th–94th |  |

−0.06 (−0.23, 0.11) | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.09) | −0.06 (−0.21, 0.09) | −0.07 (−0.21, 0.08) |

| ≥95th |  |

−0.20 (−0.36, −0.04)* | −0.20 (−0.36, −0.03)* | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.07)† | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.07)† |

| P for trend a | 0.077 | 0.134 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| <85th |  |

REF | REF | REF | REF |

| ≥85th |  |

−0.13 (−0.26, 0.00)* | −0.14 (−0.27, −0.01)* | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.01)* | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.01)* |

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||

|

<85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

|

85th–94th | −0.13 (−0.32, 0.05) | −0.16 (−0.34, 0.03) | −0.25 (−0.41, −0.08)† | −0.24 (−0.40, −0.08)† |

|

≥95th | −0.20 (−0.34, −0.05)† | −0.19 (−0.34, −0.04)* | −0.28 (−0.41, −0.15)§ | −0.27 (−0.40, −0.14)§ |

| P for trend a | 0.028 | 0.034 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

<85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

|

≥85th | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.05)† | −0.18 (−0.31, −0.05)† | −0.26 (−0.38, −0.15)§ | −0.25 (−0.37, −0.14)§ |

| BMI Trajectories | |||||

| Ages 2–4 | Ages 5–7 | ||||

| <85th | <85th | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| <85th | ≥85th | −0.07 (−0.27, 0.13) | −0.08 (−0.28, 0.12) | −0.37(−0.54, −0.19)§ | −0.35(−0.53, −0.18)§ |

| ≥85th | <85th | 0.04 (−0.18, 0.25) | 0.02 (−0.19, 0.24) | −0.08 (−0.28, 0.12) | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.10) |

| ≥85th | ≥85th | −0.21 (−0.36, −0.07)† | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.07)† | −0.24(−0.37, −0.11)§ | −0.23(−0.36, −0.10)§ |

| P for interaction b | 0.286 | 0.338 | 0.109 | 0.091 | |

Associations presented as β (95%CI). Adjusted βs are adjusted for maternal race, maternal education level, maternal marital status, smoking during pregnancy, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI category, maternal age at menarche, maternal diabetes, low birthweight status, and preterm birth status.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

P values for trend are based on linear regression models using BMI z-scores as a continuous variable

P values for interaction are based on models including an interaction term between BMI category at 2–4 years and BMI category at 5–7 years.

Acknowledgments

TBoston Birth Cohort (the parent study) is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2R01HD041702, R01HD086013, R01HD098232, and R01ES031272); the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (R40MC27443, UJ2MC31074). L-K.C. was also supported in part by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (TL1 TR003100), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. G.W. was also supported in part by the NIH/National Institute of Environmental Health Science (R03ES029594). The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting agencies. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- APHV

Age at peak height velocity

- BMC

Boston Medical Center

- BMI

Body-mass index

- FSH

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

Footnotes

Data Statement: The data is not publicly available but is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and after institutional review board review and approval.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Jacobsen B, Oda K, Knutsen S, Fraser G. Age at menarche, total mortality and mortality from ischaemic heart disease and stroke: the Adventist Health Study, 1976–88. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:245–52. 10.1093/ije/dyn251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Prentice P, Viner RM. Pubertal timing and adult obesity and cardiometabolic risk in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2013;37:1036–43. 10.1038/ijo.2012.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Qiu C, Chen H, Wen J, Zhu P, Lin F, Huang B, et al. Associations between age at menarche and menopause with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis in Chinese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:1612–21. 10.1210/jc.2012-2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cooper GS, Ephross SA, Weinberg CR, Baird DD, Whelan EA, Sandler DP. Menstrual and reproductive risk factors for ischemic heart disease. Epidemiol Camb Mass 1999;10:255–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Elks CE, Ong KK, Scott RA, van der Schouw YT, Brand JS, Wark PA, et al. Age at Menarche and Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3526–34. 10.2337/dc13-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Heys M, Schooling CM, Jiang C, Cowling BJ, Lao X, Zhang W, et al. Age of Menarche and the Metabolic Syndrome in China. Epidemiology 2007;18:740–746. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181567faf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Frontini MG, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Longitudinal changes in risk variables underlying metabolic Syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood in female subjects with a history of early menarche: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord J Int Assoc Study Obes 2003;27:1398–404. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lakshman R, Forouhi NG, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Bingham SA, Khaw K-T, et al. Early Age at Menarche Associated with Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:4953–60. 10.1210/jc.2009-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hardy R, Kuh D, Whincup PH, Wadsworth ME. Age at puberty and adult blood pressure and body size in a British birth cohort study. J Hypertens 2006;24:59–66. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000198033.14848.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Remsberg KE, Demerath EW, Schubert CM, Chumlea WC, Sun SS, Siervogel RM. Early menarche and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescent girls: the Fels Longitudinal Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:2718–24. 10.1210/jc.2004-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee Y, Styne D. Influences on the onset and tempo of puberty in human beings and implications for adolescent psychological development. Horm Behav 2013;64:250–61. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mrug S, Elliott MN, Davies S, Tortolero SR, Cuccaro P, Schuster MA. Early Puberty, Negative Peer Influence, and Problem Behaviors in Adolescent Girls. Pediatrics 2014;133:7–14. 10.1542/peds.2013-0628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mendle J, Ryan RM, McKone KMP. Age at Menarche, Depression, and Antisocial Behavior in Adulthood. Pediatrics 2018;141. 10.1542/peds.2017-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Patton GC, McMorris BJ, Toumbourou JW, Hemphill SA, Donath S, Catalano RF. Puberty and the Onset of Substance Use and Abuse. Pediatrics 2004;114:e300–6. 10.1542/peds.2003-0626-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stice E, Presnell K, Bearman SK. Relation of early menarche to depression, eating disorders, substance abuse, and comorbid psychopathology among adolescent girls. Dev Psychol 2001;37:608–19. 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Graber JA. Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Horm Behav 2013;64:262–9. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M, Rantanen P, Rimpelä M. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1055–64. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00480-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Velie EM, Nechuta S, Osuch JR. Lifetime reproductive and anthropometric risk factors for breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Breast Dis 2005;24:17–35. 10.3233/bd-2006-24103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Day FR, Elks CE, Murray A, Ong KK, Perry JRB. Puberty timing associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and also diverse health outcomes in men and women: the UK Biobank study. Sci Rep 2015;5. 10.1038/srep11208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Charalampopoulos D, McLoughlin A, Elks CE, Ong KK. Age at Menarche and Risks of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180:29–40. 10.1093/aje/kwu113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi A, For the JACC Study Group. Early age at menarche associated with increased all-cause mortality. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:771–8. 10.1007/s10654-011-9623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Giles LC, Glonek GF, Moore VM, Davies MJ, Luszcz MA. Lower age at menarche affects survival in older Australian women: results from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health 2010;10:341. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jacobsen BK, Heuch I, Kvåle G. Association of Low Age at Menarche with Increased All-Cause Mortality: A 37-Year Follow-up of 61,319 Norwegian Women. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1431–7. 10.1093/aje/kwm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sørensen K, Mouritsen A, Aksglaede L, Hagen CP, Mogensen SS, Juul A. Recent secular trends in pubertal timing: implications for evaluation and diagnosis of precocious puberty. Horm Res Paediatr 2012;77:137–45. 10.1159/000336325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Aksglaede L, Olsen LW, Sørensen TIA, Juul A. Forty Years Trends in Timing of Pubertal Growth Spurt in 157,000 Danish School Children . PLoS ONE 2008;3. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Anderson SE, Must A. Interpreting the continued decline in the average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of U.S. girls studied 10 years apart. J Pediatr 2005;147:753–60. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Demerath EW, Towne B, Chumlea WC, Sun SS, Czerwinski SA, Remsberg KE, et al. Recent decline in age at menarche: The Fels Longitudinal Study. Am J Hum Biol 2004;16:453–7. 10.1002/ajhb.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ohlsson C, Bygdell M, Celind J, Sondén A, Tidblad A, Sävendahl L, et al. Secular Trends in Pubertal Growth Acceleration in Swedish Boys Born From 1947 to 1996. JAMA Pediatr 2019. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Eckert-Lind C, Busch AS, Petersen JH, Biro FM, Butler G, Bräuner EV, et al. Worldwide Secular Trends in Age at Pubertal Onset Assessed by Breast Development Among Girls: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:e195881–e195881. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sørensen K, Aksglaede L, Petersen JH, Juul A. Recent changes in pubertal timing in healthy Danish boys: associations with body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:263–70. 10.1210/jc.2009-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Li W, Liu Q, Deng X, Chen Y, Liu S, Story M. Association between Obesity and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14. 10.3390/ijerph14101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sandhu J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Cole TJ, Holly J, Davey Smith G. The impact of childhood body mass index on timing of puberty, adult stature and obesity: a follow-up study based on adolescent anthropometry recorded at Christ’s Hospital (1936–1964). Int J Obes 2005 2006;30:14–22. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Juul A, Magnusdottir S, Scheike T, Prytz S, Skakkebæk NE. Age at voice break in Danish boys: effects of pre-pubertal body mass index and secular trend. Int J Androl 2007;30:537–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Aksglaede L, Juul A, Olsen LW, Sørensen TIA. Age at Puberty and the Emerging Obesity Epidemic. PLoS ONE 2009;4. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Crocker MK, Stern EA, Sedaka NM, Shomaker LB, Brady SM, Ali AH, et al. Sexual Dimorphisms in the Associations of BMI and Body Fat with Indices of Pubertal Development in Girls and Boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:E1519–29. 10.1210/jc.2014-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee JM, Kaciroti N, Appugliese D, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Lumeng JC. Body Mass Index and Timing of Pubertal Initiation in Boys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:139–44. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kleber M, Schwarz A, Reinehr T. Obesity in children and adolescents: relationship to growth, pubarche, menarche, and voice break. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2011;24:125–30. 10.1515/jpem.2011.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang Y Is obesity associated with early sexual maturation? A comparison of the association in American boys versus girls. Pediatrics 2002;110:903–10. 10.1542/peds.110.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bygdell M, Kindblom JM, Celind J, Nethander M, Ohlsson C. Childhood BMI is inversely associated with pubertal timing in normal-weight but not overweight boys. Am J Clin Nutr 2018. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lundeen EA, Norris SA, Martorell R, Suchdev PS, Mehta NK, Richter LM, et al. Early Life Growth Predicts Pubertal Development in South African Adolescents123. J Nutr 2016;146:622–9. 10.3945/jn.115.222000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Busch AS, Hollis B, Day FR, Sørensen K, Aksglaede L, Perry JRB, et al. Voice break in boys—temporal relations with other pubertal milestones and likely causal effects of BMI. Hum Reprod 2019;34:1514–22. 10.1093/humrep/dez118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Busch AS, Højgaard B, Hagen CP, Teilmann G. Obesity Is Associated with Earlier Pubertal Onset in Boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e1667–72. 10.1210/clinem/dgz222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Boyne MS, Thame M, Osmond C, Fraser RA, Gabay L, Reid M, et al. Growth, Body Composition, and the Onset of Puberty: Longitudinal Observations in Afro-Caribbean Children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:3194–200. 10.1210/jc.2010-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bundak R, Darendeliler F, Gunoz H, Bas F, Saka N, Neyzi O. Analysis of puberty and pubertal growth in healthy boys. Eur J Pediatr 2007;166:595–600. 10.1007/s00431-006-0293-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Baird J, Walker I, Smith C, Inskip H. Review of methods for determining pubertal status and age of onset of puberty in cohort and longitudinal studies. London, UK: CLOSER; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Roche AF, Sievogel RM, Chumlea WC, Webb P. Grading body fatness from limited anthropometric data. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:2831–8. 10.1093/ajcn/34.12.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Use of the body mass index (BMI) as a measure of overweight in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 1998;132:191–3. 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity Evaluation and Treatment: Expert Committee Recommendations. Pediatrics 1998;102:e29–e29. 10.1542/peds.102.3.e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang G, Divall S, Radovick S, Paige D, Ning Y, Chen Z, et al. Preterm Birth and Random Plasma Insulin Levels at Birth and in Early Childhood. JAMA 2014;311:587–96. 10.1001/jama.2014.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li M, Fallin MD, Riley A, Landa R, Walker SO, Silverstein M, et al. The Association of Maternal Obesity and Diabetes With Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Pediatrics 2016;137. 10.1542/peds.2015-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Azuine RE, Ji Y, Chang H-Y, Kim Y, Ji H, DiBari J, et al. Prenatal Risk Factors and Perinatal and Postnatal Outcomes Associated With Maternal Opioid Exposure in an Urban, Low-Income, Multiethnic US Population. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Defining Childhood Obesity | Overweight & Obesity | CDC; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html (accessed October 15, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cole TJ. Optimal design for longitudinal studies to estimate pubertal height growth in individuals. Ann Hum Biol 2018;45:314–20. 10.1080/03014460.2018.1453948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cole TJ, Pan H, Butler GE. A mixed effects model to estimate timing and intensity of pubertal growth from height and secondary sexual characteristics. Ann Hum Biol 2014;41:76–83. 10.3109/03014460.2013.856472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bleil ME, Booth-LaForce C, Benner AD. Race disparities in pubertal timing: Implications for cardiovascular disease risk among African American women. Popul Res Policy Rev 2017;36:717–38. 10.1007/s11113-017-9441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ, Fang MZ, Gardner WP, Pajer K. African-American/White Differences in the Age of Menarche: Accounting for the Difference. Soc Sci Med 1982 2012;75:1263–70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ramnitz MS, Lodish MB. Racial Disparities in Pubertal Development. Semin Reprod Med 2013;31:333–9. 10.1055/s-0033-1348891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hiatt RA, Stewart SL, Hoeft KS, Kushi LH, Windham GC, Biro FM, et al. Childhood Socioeconomic Position and Pubertal Onset in a Cohort of Multiethnic Girls: Implications for Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark 2017;26:1714–21. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Webster GD, Graber JA, Gesselman AN, Crosier BS, Schember TO. A Life History Theory of Father Absence and Menarche: A Meta-Analysis. Evol Psychol 2014;12:147470491401200200. 10.1177/147470491401200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mendle J, Turkheimer E, D’Onofrio BM, Lynch SK, Emery RE, Slutske WS, et al. Family structure and age at menarche: a children-of-twins approach. Dev Psychol 2006;42:533–42. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Sørensen S, Brix N, Ernst A, Lauridsen LLB, Ramlau-Hansen CH. Maternal age at menarche and pubertal development in sons and daughters: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 2018;33:2043–50. 10.1093/humrep/dey287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kubo A, Ferrara A, Laurent CA, Windham GC, Greenspan LC, Deardorff J, et al. Associations Between Maternal Pregravid Obesity and Gestational Diabetes and the Timing of Pubarche in Daughters. Am J Epidemiol 2016;184:7–14. 10.1093/aje/kww006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kubo A, Deardorff J, Laurent CA, Ferrara A, Greenspan LC, Quesenberry CP, et al. Associations Between Maternal Obesity and Pregnancy Hyperglycemia and Timing of Puberty Onset in Adolescent Girls: A Population-Based Study. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:1362–9. 10.1093/aje/kwy040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lauridsen LLB, Arendt LH, Ernst A, Brix N, Parner ET, Olsen J, et al. Maternal diabetes mellitus and timing of pubertal development in daughters and sons: a nationwide cohort study. Fertil Steril 2018;110:35–44. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Brix N, Ernst A, Lauridsen LLB, Parner ET, Olsen J, Henriksen TB, et al. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Timing of Puberty in Sons and Daughters: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2019;188:47–56. 10.1093/aje/kwy206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C. MICE: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shalitin S, Phillip M. Role of obesity and leptin in the pubertal process and pubertal growth--a review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord J Int Assoc Study Obes 2003;27:869–74. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Martos-Moreno GÁ, Chowen JA, Argente J. Metabolic signals in human puberty: Effects of over and undernutrition. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010;324:70–81. 10.1016/j.mce.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Casazza K, Goran MI, Gower BA. Associations among Insulin, Estrogen, and Fat Mass Gain over the Pubertal Transition in African-American and European-American Girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2610–5. 10.1210/jc.2007-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Dunger DB, Ahmed ML, Ong KK. Early and late weight gain and the timing of puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2006;254–255: 140–5. 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Widerøe M, Vik T, Jacobsen G, Bakketeig LS. Does maternal smoking during pregnancy cause childhood overweight? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2003;17:171–9. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wang G, Walker SO, Hong X, Bartell TR, Wang X. Epigenetics and Early Life Origins of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:S14–21. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Okorodudu DO, Jumean MF, Montori VM, Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Erwin PJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2005. 2010;34:791–9. 10.1038/ijo.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.