Abstract

Background

Cognitive deficits are present in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR-P). We developed Cognition for Learning and for Understanding Everyday Social Situations (CLUES), an integrated social- and neurocognitive remediation intervention for CHR-P, and examined its feasibility and efficacy compared to an active control intervention in a pilot randomized controlled trial.

Method

Thirty-eight individuals at CHR-P were randomized to CLUES or Enriched Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (EnACT). Participants were assessed at baseline, end of treatment and 3-month follow-up for changes in social/role functioning, neuro- and social cognition, and symptoms.

Results

Social functioning significantly improved for participants in CLUES over EnACT, at end of treatment and 3-month follow-up. CLUES participants also showed greater improvements in social cognition (theory of mind and managing emotions).

Conclusion

The results support feasibility of CLUES and suggest preliminary efficacy. Future randomized controlled trials of CLUES in a larger sample, with additional treatment sites, could help determine efficacy of CLUES, and investigate whether CLUES can be effectively implemented in other settings.

Introduction

Cognitive deficits, while a core feature of schizophrenia (Green et al., 2000), are also present during the clinical high risk (CHR) phase of the illness (Giuliano et al., 2012). Intervention and cognitive remediation during this critical period of illness may prevent further decline. We developed Cognition for Learning and for Understanding Everyday Social Situations (CLUES), a social cognitive and neurocognitive remediation intervention designed for youth at CHR for psychosis. CLUES was inspired and modeled after Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET; (Hogarty et al., 2004)), a comprehensive cognitive rehabilitation program that improves cognition, social cognition, and employment in early course and chronic schizophrenia (Eack et al., 2009; Eack et al., 2011). CLUES is a 6-month intervention that includes several components, including: 1) One hour per week computer-based cognitive enhancement exercises done in pairs with a peer and a coach, 2) a 22-session social cognitive group focused on increasing skills for perspective taking, clear communication, and acting wisely in social situations, 3) weekly individual coaching sessions aimed at developing skills to work towards specific social and role functioning goals, and 4) at least 1 hour per week online cognitive training exercises. Full development and description of the CLUES intervention is discussed elsewhere (Friedman-Yakoobian et al., 2019, including online supplemental materials) and CLUES was found to significantly improve social functioning in an uncontrolled pilot study.

The current study investigated the efficacy of the CLUES intervention in a small, randomized controlled feasibility trial. CLUES was compared to an active control intervention, EnACT (Enriched Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), which was designed to include similar components to CLUES (individual, group, and computer) but without cognitive remediation. EnACT is a multifaceted acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) intervention, including weekly individual sessions for 24 weeks, an 11-session group, 1 hour per week of online, computerized trivia exercises, and family psychoeducation. ACT has a growing evidence base for efficacy in individuals with psychosis (Louise, Fitzpatrick, Strauss, Rossell, and Thomas, 2018) and components of ACT have been included in CLUES in order to enhance motivation and engagement in the various components of this treatment.

Methods

Participants were recruited via social media, online advertisements, clinicians, schools, and universities. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Ages 15–30, 2) At least moderate difficulty with motivation, organization, or flexibility, causing disruption in social and role functioning as measured by an assessment of cognitive styles and social cognition (Styles of Thinking Assessment and Rating Scale, Gnong-Granato et al., Unpublished), 3) Met Criteria of Prodromal States (COPS) on the Structured Interview for Psychosis Risk Symptoms (SIPS, Miller et al., 2003), or met early, broad criteria for CHR (Keshavan et al., 2011). Exclusion criteria were: 1) a full psychotic disorder, 2) significant neurological or medical disorders causing cognitive impairment, 3) DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence in the past 3 months, 4) <6th grade reading level, and 5) current, persistent suicidal or homicidal behavior.

Participants were assessed at baseline, end of treatment (approximately 6 months after baseline), and at 3-month post-treatment follow-up by trained, reliable raters and testers who were blind to treatment assignment. At baseline, participants received a demographics questionnaire and were assessed with the Wide Range Achievement Test 4th Edition Word Reading Subtest (WRAT; Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006). The primary target clinical outcome (social and role functioning) was assessed with the Global Functioning Social and Role Scales (Cornblatt et al., 2007; Niendam et al., 2006). Secondary measures included attenuated psychotic symptoms, assessed with the Structured Interview for Psychosis Risk Symptoms (SIPS; Miller et al., 2003), and cognition. We assessed processing speed (Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia, BACS, symbol coding subtest, Keefe et al., 2004; Nuechterlein et al., 2008), working memory (Letter number span, LNS, Gold et al., 1997), verbal learning (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, HVLT, Brandt and Benedict, 2001), visual learning (Brief Visuospatial Memory Test, BVMT, Benedict, 1997), reaction time (Orientation Remedial Module Reaction Time Test, ORM, Ben-Yishay, 1981), managing emotions (managing emotions subtest of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, MSCEIT, Mayer et al., 2003), emotion recognition (Penn ER40, Kohler et al., 2003), and theory of mind (The Awareness of Social Inference Test, TASIT, McDonald et al., 2006).

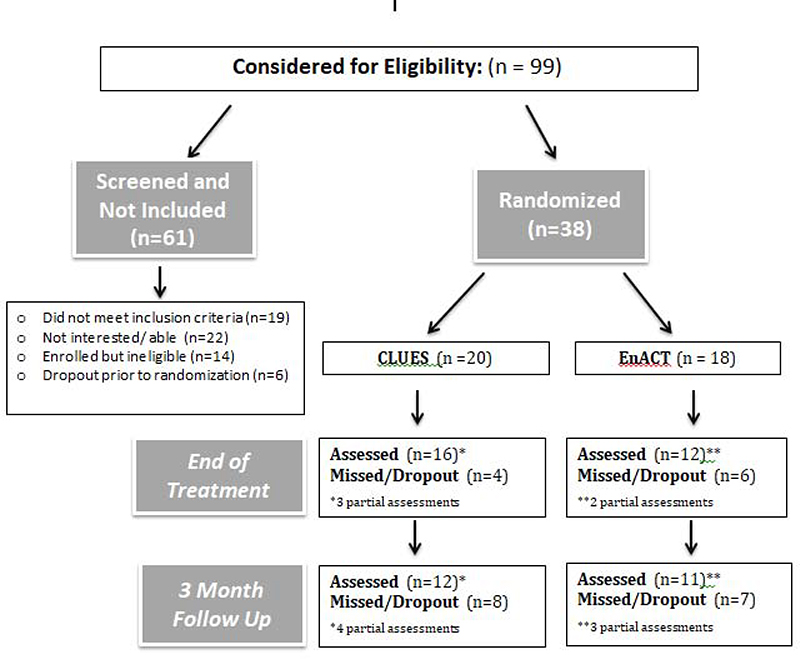

Twenty participants were randomized into CLUES and 18 participants were randomized into EnACT. Nine participants in each group completed all three assessment timepoints. See Figure 1 for full CONSORT diagram with details about attrition and partial assessments completed at each time point for CLUES and EnACT.

Figure 1.

CLUES Randomized Controlled Trial CONSORT Diagram

Efficacy of CLUES relative to EnACT was estimated using intent-to-treat linear mixed effects model with all 38 randomized participants, with missing data estimated at the time of analysis using the expectation-maximization approach (Dempster et al., 1977). We examined treatment (CLUES vs. EnACT) by time (baseline, end of treatment, and follow up) interactions with random intercepts and slopes. The main effect of interest was the treatment by time interaction.

Results

At baseline, participants in CLUES and EnACT were similar in demographic characteristics including age, sex, race, highest level of education, and premorbid estimated IQ. There were no significantly different baseline demographic characteristics, all p>.220. See Table 1 for full demographic characteristics. There were significant differences at baseline between the two groups for negative symptoms [t(36)=−3.69, p < .001, with the CLUES group having more negative symptoms at baseline] and the BVMT [t(28.8)=−2.09, p=.045, with the EnACT group having worse visual memory at baseline]. There were no other significant baseline outcome measure differences. See Table 2 for means and standard error for each measure. Of note, raw scores are included in Table 2 and were used for analysis of cognitive and social-cognitive measures as there are no widely established norms for the younger end of the age group (15–18) included in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic and cognitive characteristics

| CLUES (n=20) | EnACT (n=18) | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M (SD) | M (SD) | T or X2 |

| Age (range=15–26) | 19.2 (2.92) | 19.1 (3.02) | 0.10 (p = .923) |

| Sex (M/F/Other) | 11 / 6 / 3 | 12 / 4 / 2 | 0.54 (p = .764) |

| Race (White/AA/Interracial/Asian) | 12 / 2 / 4 / 1 (1 missing) | 9 / 4 / 2 / 3 | 5.73 (p = .220) |

| Highest Level of Education (Primary School/Some high school/High school/College) | 2 / 4 / 11 / 2 (1 missing) | 1 / 7 / 7 / 3 | 3.99 (p = .407) |

| Premorbid Estimated IQ | 106 (9.65) | 102 (12.7) | −0.99 (p = .331) |

| Total SIPS Positive Symptoms | 12.8 (1.2) | 13.6 (1.1) | 0.51 (p = .615) |

| Total SIPS Negative Symptoms | 16.8 (1.1) | 10.9 (1.2) | −3.69* (p < .001) |

| Global functioning social** | 5.5 (0.3) | 6.2 (0.3) | 1.63 (p = .112) |

| Global functioning role** | 5.2 (0.5) | 6.2 (0.5) | 1.66 (p = .106) |

Indicates significant at the p < .05 level

5= Serious Impairment , 6= Moderate Impairment

Table 2.

Outcome measure means and results

| Measure | Treatment | Baseline M(SE) | End of Treatment M(SE) | BL vs ET interaction? | Follow Up M(SE) | BL vs FU interaction? | Timepoint x Treatment Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Functioning Social (GFS) | CLUES | 5.5 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.3) |

t(39)=2.45, *p=.019, d=0.72 |

6.6 (0.4) |

t(39)=2.52, *p=.016, d=1.04 |

F(2,39)=4.16, *p=.023 |

| EnACT | 6.2 (0.3) | 5.8 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.3) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Global Functioning Role (GFR) | CLUES | 5.2 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.5) |

t(39)=0.79, p=432, d=0.29 |

6.8 (0.7) |

t(39)=1.06, p=.433, d=0.51 |

F(2,39)=0.60, p=.555 |

| EnACT | 6.2 (0.5) | 6.5 (0.5) | 6.8 (0.7) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| MSCEIT Managing Emotions | CLUES | 92.4 (1.8) | 95.9 (2.1) |

t(34)=1.91, p=.064, d=0.54 |

100.6 (3.0) |

t(34) = 2.21, *p=.034, d=0.99 |

F(2,34)=2.76, p=.077 |

| EnACT | 90.4 (1.8) | 89.8 (2.3) | 91.1 (2.9) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| TASIT Theory of Mind | CLUES | 54.5 (1.1) | 57.2 (1.3) |

t(33) = 2.57, *p=.015, d = 1.00 |

57.0 (1.8) |

t(33)=0.97, p=.338, d=0.47 |

F(2,33)=3.31, *p=.049 |

| EnACT | 53.6 (1.2) | 51.4 (1.5) | 53.9 (1.6) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| ER40 Emotion Recognition | CLUES | 33.5 (0.6) | 33.6 (0.7) |

t(33)=1.62, p=.115, d=0.78 |

34.0 (1.1) |

t(33)=0.02, p=.982, d=0.01 |

F(2,33)=1.49, p=.241 |

| EnACT | 33.7 (0.6) | 31.9 (0.8) | 34.2 (0.9) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| SIPS Positive Symptoms | CLUES | 12.8 (1.2) | 8.0 (1.2) |

t(39)=−0.33, p=.741, d=0.12 |

4.9 (1.6) |

t(39)=−0.30, p=.764, d= −0.14 |

F(2,39)=0.07, p=.931 |

| EnACT | 13.6 (1.1) | 9.3 (1.3) | 6.3 (1.6) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| SIPS Negative Symptoms | CLUES | 16.8 (1.1) | 11.8 (1.6) |

t(37)=−1.46, p=.154, d=−0.73 |

9.1 (2.9) |

t(37)=−1.23, p=.228, d =−0.99 |

F(2,37)=1.15, p=.327 |

| EnACT | 10.9 (1.2) | 9.6 (1.9) | 8.1 (2.8) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| ORM (Reaction time) | CLUES | 219 (8.5) | 203 (6.7) |

t(34)=−0.06, p=.955, d=−0.01 |

215 (8.7) |

t(34)=0.41, p=.684, d=0.16 |

F(2,34)=0.16, p=.856 |

| EnACT | 228 (8.7) | 213 (7.4) | 217 (7.9) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| HVLT (Verbal Memory) | CLUES | 28.3 (1.2) | 25.8 (1.5) |

t(34)=−1.28, p=.208, d=−0.57 |

25.9 (2.7) |

t(34)=−0.16, p=.874, d=−0.11 |

F(2,34)=1.00, p=.378 |

| EnACT | 25.7 (1.2) | 26.2 (1.8) | 23.9 (2.5) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| BVMT (Visual Memory) | CLUES | 26.4 (1.6) | 26.0 (1.7) |

t(29)=−1.81, p=.080, d =−0.64 |

26.7 (2.6) |

t(29)=−0.85, p=.400, d=−0.46 |

F(2,29)=1.69, p=.202 |

| EnACT | 20.8 (1.6) | 24.5 (1.9) | 24.1 (2.5) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| BACS Symbol coding | CLUES | 62.0 (3.0) | 66.4 (3.5) |

t(34)=0.25, p=.906, d=0.07 |

69.8 (5.2) |

t(34)=0.54, p=.596, d=0.26 |

F(2,34)=0.15, p=.864 |

| EnACT | 59.3 (3.1) | 62.8 (3.9) | 63.7 (5.1) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| LNS Working Memory | CLUES | 15.6 (0.8) | 15.9 (1.0) |

t(34)=−1.23, p=.226, d=−0.33 |

16.4 (1.4) |

t(34)=−0.04, p=.971, d =−0.01 |

F(2,34)=1.02, p=.371 |

| EnACT | 15.2 (0.9) | 16.7 (1.1) | 16.0 (1.4) | ||||

p<.05

Key: MSCEIT = Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; TASIT = The Awareness of Social Inference Test; ER40 = Emotion Recognition 40; SIPS = Structured Interview for Psychosis Risk Symptoms; ORM = Orientation Remedial Module Reaction Time; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; BVMT = ; BACS = Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; LNS = Letter Number Span.

Raw scores are used for all measures as there are no established norms for the (15–18 year olds) that participated in this study.

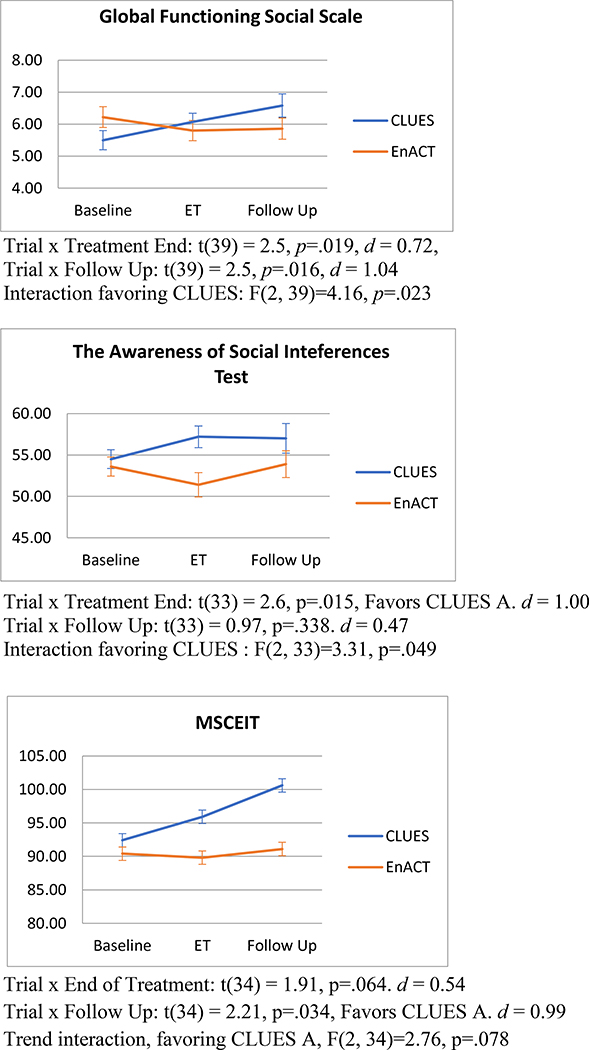

There was a significant treatment group by time interaction for the Global Functioning Social Scale (GFS) at end of treatment [t(39) = 2.5, p=.019, Cohen’s d = 0.72] and at 3 month follow up [t(39) = 2.5, p=.016, Cohen’s d = 1.04] both favoring CLUES. Analysis of the linear trend across all time points (including 3 month follow-up) revealed a significant overall time by treatment group interaction for social functioning [F(2,39)=4.16, p=.023] favoring CLUES. There were also significant differential effects over time between the treatment groups for two of the social cognition measures. For theory of mind measured by the TASIT, there was a significant interaction at end of treatment [t(33) = 2.57, p=.015, Cohen’s d = 1.00] also favoring CLUES, but not at follow-up [t(33)=0.97, p=.338, Cohen’s d=0.47]. However, the overall time point by treatment group interaction for the TASIT was significant [F(2,33)=3.31, p=.049]. For the MSCEIT managing emotions subtest, there was a significant treatment by time interaction at 3-month follow up, [t(34) = 2.21, p=.034, Cohen’s d = 0.99] favoring CLUES. An ANOVA revealed a trending overall time point by treatment group interaction for the MSCEIT [F(2,34)=2.76, p=.077].

In regard to attenuated psychotic symptoms, total positive symptoms measured by the SIPS improved for both groups over time at end of treatment [t(39)= −3.5, p=.001] and follow up [t(39)= −5.1, p<.001]. Although both groups improved overall in positive symptoms, one participant in EnACT developed full psychotic symptoms during the course of the trial, whereas no participants in CLUES experienced a transition to full psychosis. No significant differences were observed in positive symptoms over time between treatment groups [F(2, 39)=0.07, p=0.93].

For neurocognitive measures, there were no significant differences between CLUES and EnACT. Both groups showed significant improvements in visual memory [t(29)=2.2, p<.001] and reaction time at the end of treatment [t(34)= −2.3, p=.030]. All other results were not statistically significant. See Table 2 for details.

We additionally examined adherence to the components of CLUES and EnACT treatment conditions and found that adherence was variable and relatively poor in both groups (See Table 3 for details). Adherence to the home computer training was highest, with 40% of participants completing at least 70% of the recommended training sessions. However, more than half the participants completed less than 30% of the recommended training. Adherence to individual coaching sessions was a bit more consistent, with 35% completing 70% of the offered sessions and only 15% completing less than 30% of recommended sessions. Group and paired computer training was more variable, with few participants completing 70% of the recommended sessions and a larger proportion completing between 30–69% of sessions. Similarly in the EnACT condition, participation was variable, with highest adherence to the individual sessions (28.9% completing at least 70% of sessions), with lower adherence in the group and at-home computer components.

Table 3.

Adherence to CLUES and EnACT Treatment Components

| Group | Paired Computer | Individual Coaching | Home computer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLUES | 22 sessions | 24 sessions | 24 sessions | 440 exercises | |

| Most | 15% | 15% | 35% | 40% | |

| Some | 55% | 45% | 50% | 5% | |

| A bit | 15% | 25% | 10% | 50% | |

| None | 15% | 15% | 5% | 5% | |

| EnACT | 11 sessions | n/a | 24 sessions | 44 sessions | |

| Most | 22.2% | n/a | 38.9% | 27.8% | |

| Some | 22.2% | n/a | 22.2% | 16.7% | |

| A bit | 22.2% | n/a | 16.7% | 16.7% | |

| None | 33.3% | n/a | 16.7% | 38.9% |

Most= 70–100%, Some=30–69%, A bit= 1–29%, None=0

Discussion

The results of this pilot randomized controlled trial indicate preliminary efficacy of the CLUES treatment for improving social functioning and social cognition when compared to another robust treatment condition that included individual, group and family components. These results confirm the findings of the open trial of the CLUES treatment, in which CLUES participants improved in social functioning (Friedman-Yakoobian et al., 2019). To our knowledge, no other published treatments for youth at CHR have reported improvements in social functioning (Devoe et al., 2018).

Of note, a lack of widely established clinical norms across the age group studied in CLUES limits the interpretation of clinical significance of these findings. However, we observed medium to large effect sizes (d = .72 to d = 1.04) for all improvements observed in CLUES relative to EnACT. Future work to establish clinical norms and examine clinical significance for observed effects is warranted.

Although social cognitive measures improved for CLUES participants, neurocognitive improvements were not observed. Neurocognition also did not improve for participants in the open trial of CLUES. As previously noted (Friedman-Yakoobian et al., 2019), some possible reasons for this may be that CLUES (especially the group and individual sessions) focuses more on social cognition training than neurocognitive training and participants were not selected for neurocognitive impairments. Further improvements of CLUES could involve selecting participants with specific cognitive difficulties and augmenting cognitive training to match specific cognitive deficits of participants.

Regarding the question of feasibility, the current study is limited by a small sample size and attrition in both groups prior to the final assessment. Rates of attrition in this study were higher than that observed in the open trial of CLUES (Friedman-Yakoobian et al., 2019). Some observations of what may have caused this included: 1) recruiting for two group cohorts simultaneously slowed increased the time from first assessment to start of group, with some participants needing to wait several weeks to months to start a group, and dropping out of the study in the meantime, 2) several active participants were college students who left the program early at the end of the semester for summer and/ or winter breaks, 3) some participants left the group because they were much younger or older than other group participants and did not feel they fit in, 4) some participants had increasing work or school commitments during the course of the study and were encouraged to embrace these opportunities even if it meant reduced adherence to the treatment.

Of note, improvements were seen for participants in CLUES, relative to EnACT, despite relatively poor adherence rates in both conditions. This raises the question of whether an abbreviated version of CLUES could have efficacy. A future study, dismantling and examining the components of CLUES, could be useful in figuring out which may be the most impactful and efficient elements of this treatment. Additionally, future studies investigating CLUES vs another treatment condition in a larger sample including additional treatment sites could be helpful in determining efficacy of this treatment as well to determine whether CLUES can be effectively implemented in other treatment programs.

Researchers should use caution in interpreting these results, given the small sample size and multiple statistical comparisons made without correction for Type 1 error. These outcomes were not corrected for multiple inference testing because of the feasibility nature of the study. However, future studies of CLUES investigating larger samples of participants will be important for determining the potential impact of this treatment on outcomes and the utility of CLUES as a treatment for youth at clinical high risk for psychosis.

Figure 2.

Treatment by Time Interactions

Acknowledgement

All authors of this manuscript, “Neurocognitive and social cognitive training for youth at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis: A randomized controlled feasibility trial” have reviewed and approved this version being submitted. This is the authors’ original work and it has not been published or submitted for consideration of publication elsewhere.

Role of the Funding Source

Financial support for this work came from NIMH 1R34MH105596, the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Additionally, Lumos Labs provided a 50% discount ($749.38) for participant subscriptions used for web-based cognitive training and provided weekly usage reports to the study coordinators.

None of the funding sources played any role in the writing of this manuscript or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest Statement

There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Financial support for this work came from NIMH 1R34MH105596, the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Additionally, Lumos Labs provided a 50% discount ($749.38) for participant subscriptions used for web-based cognitive training and provided weekly usage reports to the study coordinators.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ben-Yishay Y, 1981. Working approaches to remediation of cognitive deficits in brain damaged persons. New York University Medical Center, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, 1997. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB, 2001. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, Smith CW, Zinberg J, Bearden CE, Cannon TD, 2007. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 33 (3), 688–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB, 1977. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data using the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological). 39 (1), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Devoe DJ, Farris MS, Townes P, Addington J, 2018. Interventions and social functioning in youth at risk of psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley S, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS, 2009. Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia:effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 60 (11), 1468–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS, 2011. Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy on Employment Outcomes in Early Schizophrenia: Results From a Two-Year Randomized Trial. Res Soc Work Pract 21 (1), 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Yakoobian M, Parrish EM, Thomas A, Lesser R, Gnong-Granato A, Eack S, Keshavan MS, 2019. An integrated neurocognitive and social-cognitive treatment for youth at clinical high risk for psychosis: Cognition for Learning and for Understanding Everyday Social Situations (CLUES). Schizophrenia Research. 208:55–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AJ, Li H, Mesholam-Gately RI, Sorenson SM, Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ, 2012. Neurocognition in the psychosis risk syndrome: a quantitative and qualitative review. Curr Pharm Des 18 (4), 399–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnong-Granato A, Friedman Yakoobian M, Keshavan MS, Thomas A, Seidman LJ, Unpublished. Styles of Thinking Assessment and Rating Scales (STARS) Interview.

- Gold JM, Carpernter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, 1997. Auditory working memory and Wisconsin card sorting test performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J, 2000. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull 26 (1), 119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, Kechavan M, Cooley S, DiBarry AL, Garrett A, Parepally H, Zoretich R, 2004. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61 (9), 866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L, 2004. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res 68 (2–3), 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, DeLisi LE, Seidman LJ, 2011. Early and broadly defined psychosis risk mental states. Schizophr Res 126 (1–3), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, Gur RE, Gur RC, 2003. Facial Emotion Recognition in Schizophrenia: Intensity Effects and Error Pattern. American Journal of Psychiatry 160 (10), 1768–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G, 2003. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion 3 (1), 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Bornhofen C, Shum D, Long E, Saunders C, Neulinger K, 2006. Reliability and validity of The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT): a clinical test of social perception. Disability and Rehabilitation 28, 1529–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, 2003. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull 29, 703–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, McKinley M, Loewy R, O’Brien M, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Cannon TD, 2006. Neurocognitive performance and functional disability in the psychosis prodrome. Schizophrenia Research 84 (1), 100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese F.J.r., Gold JM, Goldberg T, Heaton RK, Keefe RS, Kraemer H, Mesholam-Gately RI, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Weinberger DR, Young AS, Zalcman S, Marder SR, 2008. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry 165 (2), 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ, 2006. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, FL. [Google Scholar]