Abstract

Disruption of the global nitrogen cycle by humans results primarily from activities associated with food and energy production. Since the middle of the twentieth century, human activities have more than doubled inputs of nitrogen to the Earth’s ecosystems. This new nitrogen is in chemically and biologically active forms (reactive N) and moves through the environment causing an array of health and environmental problems. Research published in Ambio for the past three decades has been documenting this major global-scale problem and has catalyzed the formation of a science-led initiative, the International Nitrogen Initiative (INI), which has informed policies to manage the global nitrogen cycle. Currently, gaps and opportunities in nitrogen pollution policies still exist and require new interdisciplinary science to help to place the nitrogen management challenge in the context of the other environmental grand challenges of our time including climate change and biodiversity loss because their solutions will be interconnected.

Keywords: Eutrophication, Global nitrogen cycle, International Nitrogen Initiative, Nitrogen management strategies, Nitrogen pollution policies, Reactive nitrogen

Introduction

For the past 50 years, Ambio has been documenting the ways humans are altering the Earth system through a suite of enterprises such as agriculture, industry, fishing, and international commerce. These activities have had many effects, including: reshaping the land surface through cropping; forestry and urbanization; adding or removing species in many of the Earth's ecosystems; and altering the major biogeochemical cycles.

Human disruption of the global nitrogen (N) cycle has been dramatic, especially since the middle of the twentieth century, primarily as the result of activities associated with food and energy production. These activities have more than doubled the natural rate at which “reactive nitrogen” (Nr) enters the Earth’s ecosystems annually. The term reactive nitrogen refers to all biologically, photochemically and radiatively active N compounds in the air and in land and water ecosystems. Reactive nitrogen compounds include ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4), nitrate (NO3), nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O) and a range of organic nitrogen compounds such as urea, but Nr does not include dinitrogen gas (N2), which forms about 78% of Earth’s atmosphere. Reactive nitrogen compounds can move through and among environmental systems in what has become known as the “N cascade” (Galloway 1998; Galloway et al. 2003). The N cascade describes the sequence of transfers of Nr through environmental systems that result in changes in these systems along the way.

Ambio articles

In a set of four highly cited articles that appeared in Ambio between 1989 and 2002, the topic of human disruption of the N cycle was considered with a focus on Nr. Three of the articles deal with Nr in specific ecosystem types; terrestrial (Matson et al. 2002), river (Caraco and Cole 1999), and marine (Elmgren 1989) ecosystems. The fourth article (Galloway and Cowling 2002) documents changes in the sources, magnitudes and consequences of changes in Nr across the world over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Taken together, these four articles do several things: (1) provide a broad overview of the Nr challenge at the global scale; (2) highlight regional hot spots and identify the dominant drivers of new Nr production in each region; (3) review the complex set of biogeochemical processes that control Nr retention in and losses from land ecosystems; and 4) catalog the consequences of disruption of the global N cycle and the Nr cascade for people and the environment, including the restructuring of marine ecosystems resulting from multiple element interactions involving carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus to produce low oxygen conditions or hypoxia.

Nr production

Three major types of human activities that produce Nr across the globe are: the use of N fertilizer to increase crop productivity; the planting of N-fixing crops; and the burning of fossil fuels and biomass to meet society’s energy and transportation needs. The magnitudes and the relative importance of these three activities have changed over the last 100 years (Table 1). In the early 1900s, total annual anthropogenic Nr fluxes were small, less than 5 Tg N year−1, and dominated by fossil fuel and biomass burning. A recent estimate shows that human-caused Nr inputs to the global N cycle has increased dramatically over the twentieth century and is now approaching 200 Tg N year−1, with fertilizer use being the dominant input pathway (Battye et al. 2017).

Table 1.

Anthropogenic activities that create Nr and changes over time.

Modified from Battye et al. (2017)

| Sources Tg N year−1 |

1910 | 1960 | Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer | 1 | 12 | 110 |

| N-fixing crops | 0.4 | 12 | 43 |

| NOx from combustion | 2.5 | 15 | 38 |

| Total | 3.9 | 39 | 191 |

Nr in the earth system

Thresholds for human and ecosystem health have been exceeded as Nr pollution increases across the globe (Rockström et al. 2009). Much of this new Nr ends up in the environment, accumulating in land systems, polluting waterways and the coastal zone, and adding a number of gases to the atmosphere. Air quality has been lowered by increases in atmospheric levels of Nr compounds, such as NH3 and NOx. The result is more smog, more fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), and higher ground-level ozone that compromise peoples’ health (Lelieveld et al. 2017). Surface water eutrophication and nitrate accumulation in shallow groundwater compromise the safety of drinking water (UNEP 2007; Tomich et al. 2016). Heavy and persistent application of N fertilizer causes soil acidification, restricting the sustainable development of agriculture (Gu et al. 2015). Reactive nitrogen can cascade through terrestrial, river and marine ecosystems and cause changes in species composition (Elmgren 1989; Caraco and Cole 1998). These changes can reduce the capacity of affected ecosystems to provide society with essential ecosystem services (Daily 1997). A portion of the Nr processed by soil and aquatic microbes is also converted to N2O, which reenters the atmosphere (Matson et al. 2002). Nitrous oxide is a long‐lived absorber of infrared radiation, with a climate change potential approximately 300 times that of CO2 (IPCC 2013). Nitrous oxide is also associated with the depletion of stratospheric ozone (Ravishankara et al. 2009).

Call for a “Total Nr Approach”

The March 2002 issue of Ambio, the same issue in which the Matson et al. and the Galloway and Cowling articles appeared, contained a total of nine articles devoted to various aspects of the global nitrogen cycle and the challenges for society with projected increases in the amount of Nr cascading through the Earth system. Near the end of their article, Galloway and Cowling (2002) called for the scientific community to implement “a Total Nr Approach” rather than dealing with individual Nr compounds in isolation from each other and from other aspects of air, land and water management. This call to action initiated an enduring global effort.

International Nitrogen Initiative

In 2003, a new effort to pursue this holistic approach to Nr management, the International Nitrogen Initiative (INI), was set up under the duel sponsorship of the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) and the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program (IGBP). Since it was established, the INI has been a major force in providing society with the scientific knowledge to optimize nitrogen’s beneficial role in sustainable food production and to minimize nitrogen’s negative effects on human health and the environment that result from food and energy production.

The INI has been particularly effective in catalyzing nitrogen assessments at various spatial scales. Scientists active in the INI have led a number of regional nitrogen assessment efforts for global hotspots of Nr production and consumption and the effects of Nr on human health and the environment including the EU (Sutton et al. 2011), the United States (Davidson et al. 2012), China (Gu et al. 2015) and India (Abrol et al. 2017).

International Nitrogen Management System

In pursuit of a coordinated international program to mitigate the global Nr problem, a new project was launched in December of 2016. This project, “Towards the International Nitrogen Management System” (INMS—www.inms.international), is a joint effort of the INI and the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP). A major goal of the INMS is to develop the evidence base to showcase the need for effective practices for global nitrogen management and highlight options to maximize the multiple benefits of better nitrogen use. The project presents a key opportunity to pull together a global and critical mass of science evidence on the nitrogen cycle, and develops a sustained process that gets science, governments, businesses and civil society working together to build common understanding and deliver real change. A vital part of the task for INMS in the near term is to show how management of the global nitrogen cycle can deliver measurable benefits for the atmosphere, land ecosystems, fresh-water systems, marine ecosystems, the climate system and global society. A core ongoing effort of INMS is the production of the first International Nitrogen Assessment scheduled to be published in 2022.

Research challenges for the coming decades

Meeting food demands in the twenty-first century

China, India and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), each with more than a billion people in 2020, present major Nr management challenges as they work to feed their people while minimizing environment degradation. There is special urgency in the case of SSA because its population is expected to double over the next 30 years, adding an additional 1 billion people (UN Population Prospects 2019). Increasing food production in SSA will depend in part on improved management of low fertility soils including upping fertilizer use to improve crop yields (Denning et al. 2009; Sanchez et al. 2009; Reis et al. 2016).

The fate of the increase in N fertilizer to croplands in SSA and other tropical regions is not well studied and is a high priority research area for the next decade. Recently, a meta-analysis of the risk for increasing N losses from intensifying tropical agriculture, including in SSA, concluded that inputs from 50 to 150 kg N ha−1 year−1 would have substantial environmental consequences and lead to large increases in NO3 leaching and gaseous nitrogen fluxes to the atmosphere from many, but not all tropical soils (Huddell et al. 2020). Soil orders such as Oxisols and some Ultisols, which cover about 20% of SSA (Eswaran et al. 1998), have net anion exchange capacity that decreases NO3 leaching into the environment (Russo et al. 2017). Knowledge of the distribution of these soils throughout this region is being improved with a new integrated digital mapping effort by the African Soil Information Service (AfSIS 2016). Intensification and extensification of crop agriculture on these soils in SSA could be an important part of the future Nr management strategy for this region and elsewhere in the tropics (Sanchez 2019).

Hypoxia

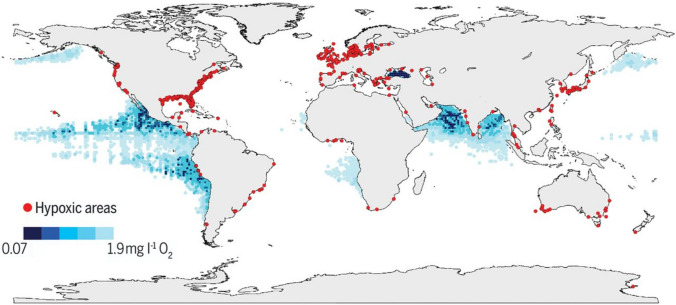

In coastal ecosystems that are strongly influenced by their watersheds (Caraco and Cole 1998), oxygen declines (hypoxia) have been caused by increased loading of N, P and organic matter from agriculture and sewage and N from the burning of fossil fuels (Elmgren 1989; Conley et al. 2011). Increases in the amount Nr fluxing into coastal waters have been growing since the middle of the twentieth century and there are now more than 500 known sites world-wide (Fig. 1, Breitburg et al. 2018). High priority research on the hypoxia problem includes finding new ways to reduce Nr inputs to coastal marine waters and the continued tracking of hypoxia across the globe through collaborative efforts such as the Global Oceans Oxygen Network (GO2NE), a UNESCO network committed to providing a global and multidisciplinary view of deoxygenation, with a focus on understanding its multiple aspects and impacts (https://en.unesco.org/go2ne).

Fig. 1.

Low and declining oxygen levels in coastal and ocean waters. Map indicates location of 500 + coastal sites where anthropogenic nutrients (especially N) have exacerbated or caused O2 dexclines to < 2 mg liter−1 (red dots). After Breitburg et al. (2018), sourced from the World Ocean Atlas (2009)

While the eutrophication of coastal marine waters is a daunting global problem, there is evidence that with appropriate interventions, trends in increasing eutrophication can be reversed. For example, the Baltic Sea countries have been working for several decades to reduce nutrient inputs and improve its eutrophication status. A recent report indicates that portions of the Baltic Sea have entered a recovery phase (Andersen et al. 2017) and a modeling study (Murray et al. 2019) shows that continued recovery is projected if countries surrounding the Baltic Sea meet the nutrient reduction targets of the Baltic Sea Action Plan (HELCOM 2013).

Scenario-based modeling

Exploring alternative futures for the nitrogen cycle over the twenty-first century is key to developing management strategies and policies from local to global scales and is a research priority. To be most useful, the nitrogen-scenarios approach should be placed in a broad framework that includes other major environmental issues such as changes in climate and land use and their associated consequences including impacts on biodiversity. This integrated framework requires an interdisciplinary approach that spans several areas in the natural and social sciences. Kanter et al. (2020b) have urged the integration of nitrogen-focused scenarios with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways used in climate research to evaluate the impact of different nitrogen production, consumption and loss trajectories in a holistic context.

Policy

Scientists have been successful in communicating the magnitude and the consequences (both positive and negative) of disruptions to the global nitrogen cycle. In response, there are now thousands of policies designed to promote the benefits and minimize problems resulting from human disruption of the global nitrogen cycle. Recently, Kanter et al. (2020a) analyzed a collection of just over 2700 policies developed by national and regional legislatures and government agencies from 186 countries. The policies consider a range of issues including: the air, land and water components of the Earth system; the economic sectors of agriculture, wastewater and industry; and policy instruments such as market mechanisms and regulatory standards. A large share of the 2700 + policies are focused on air and water and the reduction of the negative consequences of Nr pollution to protect human health and the environment. With respect to Nr and agricultural policies, Kanter et al. (2020a) found that a majority of these policies “incentivize nitrogen use and managing its commerce, demonstrating the primacy of food production over environmental concerns.”

While it is clear that there have been advances across the globe with development of policies to guide the management of anthropogenic Nr, several challenges remain. For example, there are issues of efficacy of various policies including those related to environmental and economic issues. In addition, many of the extant policies have a narrow focus (e.g., controlling the emissions of a single Nr compound from industry, promoting N fertilizer use to increase crop production) rather than the holistic approach needed to address the Nr cascade. Piece-meal solutions might solve one problem but create or exacerbate another. The INMS and UNEP’s new Interconvention Nitrogen Coordination Mechanism promises to promote important efforts that foster the holistic approach by encouraging countries to build sustainable N management road maps (UNEP 2019). In the final analysis, it will take political will to follow these science-informed roadmaps to meet the grand challenge of managing the global nitrogen cycle to ensure a sustainable future for our world.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge support from The Ecosystems Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, my academic home for more than four decades.

Jerry M. Melillo

is a Distinguished Scientist and Director Emeritus at The Ecosystems Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA. He specializes in understanding the impacts of human activities on the biogeochemistry of ecological systems from local to global scales, using a combination of field studies and simulation modeling.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abrol YP, Adhya TK, Aneja VP, Raghuram N, Pathak H, Kulshrestha U, Sharma C, Singh B, editors. The Indian nitrogen assessment: Sources of reactive nitrogen, environmental and climate effects, management options, and policies. Duxford: Woodhead Publishing (Elsevier); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- AfSIS. 2016. https://www.isric.org/projects/africa-soil-information-service-afsis.

- Andersen JH, Carstensen J, Conley DJ, Dromph K, Fleming-Lehtinen V, Gustafsson BG. Long-term temporal and spatial trends in eutrophication status of the Baltic Sea. Biol. Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2017;92(1):135–149. doi: 10.1111/brv.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battye W, Aneja VP, Schlesinger WH. Is nitrogen the next carbon? Earth’s Future. 2017 doi: 10.1002/2017EF000592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breitburg D, Levin LA, Oschlies A, Grégoire M, Chavez FP, Conley DJ, Garcon V, Golbert D, Gutierrez D, Isensee K, Jacinto GS, Limburg KE, Montes I, Naqvi SWA, Pitcher GC, Rabalais NN, Roman MR, Rose KA, Seibel BA, Telszewski M, Yasuhara M, Zhang J. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aam7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraco N, Cole J. Human impact on nitrate export: An analysis using major world rivers. Ambio. 1999;28:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Conley DJ, Carstensen J, Aigars J, Axe P, Bonsdorff E, Eremina T, Haahti B-M, Humborg C, Jonsson P, Kotta J, Lannegren C, Larsson U, Maximov A, Medina MR, Lysiak-Pastuszak E, Remeikaite-Nikine N, Walve J, Wilhelms S, Zillen L. Hypoxia is increasing in the coastal zone of the Baltic Sea. Environmental Science and Technology. 2011;45:6777–6783. doi: 10.1021/es201212r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daily G, editor. Nature’s services: Societal dependence on natural ecosystems. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1997. p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, E.A., M.B. David, J.N. Galloway, C.L. Goodale, R. Haeuber, J.A. Harrison, R.W. Howarth, D.B. Jaynes, et al. 2012. Excess nitrogen in the U.S. environment: Trends, risks, and solutions. Issues in Ecology, Report Number 15, Ecological Society of America.

- Denning G, Kabambe P, Sanchez P, Malik A, Flor R, Harawa R, Nkhoma P, Zamba C, Banda C, Magomb C, Keating M, Wangila J, Sachs J. Input subsidies to improve smallholder maize productivity in Malawi: Toward an African green revolution. PLOS Biology. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmgren R. Man’s impact on the ecosystem of the Baltic Sea: Energy flows today and at the turn of the century. Ambio. 1989;18:26–332. [Google Scholar]

- Eswaran H, Almaraz R, van den Berg E, Reich P. An assessment of the soil resources of Africa in relation to productivity. Geoderma. 1997;77:1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(97)00007-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JN. The global nitrogen cycle: Changes and consequences. Environmental Pollution. 1998;102:15–24. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)80010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JN, Aber JD, Erisman JW, Seitzinger SP, Howarth RW, Cowling EB, Cosby BJ. The nitrogen cascade. BioScience. 2003;53(4):341–356. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0341:TNC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JN, Cowling EB. Reactive nitrogen and the world: 200 years of change. Ambio. 2002;31:64–71. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B, Ju X, Chang J, Ge Y, Vitousek PM. Integrated reactive nitrogen budgets and future trends in China. PNAS. 2016;112:8792–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510211112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELCOM. 2013. Approaches and methods for eutrophication target setting in the Baltic Sea region. Baltic Sea environment proceedings 133: 147. https://www.helcom.fi/Lists/Publications/BSEP133.pdf

- Huddell L, Galford G, Tully KL, Crowley C, Palm CA, Neill C, Hickman JE, Menge DNL. Meta-analysis on the potential for increasing nitrogen losses from intensifying tropical agriculture. Global Change Biology. 2020;26:1668–1680. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2013. Climate Change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Eds. T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, and P.M. Midgley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kanter DR, Chodos O, Nordland O, Rutigliano M, Winiwarter W. Gaps and opportunities in nitrogen pollution policies around the world. Nature Sustainability. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0577-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter DR, Winiwarter W, Bodirsky BL, Bouwman L, Boyer E, Buckle S, Compton JE, Dalgaard T, de Vries W, Leclère D, Leip A, Müller C, Popp A, Raghuram N, Rao S, Sutton A, Tian H, Westhoek H, Zhang X, Zurek M. A framework for nitrogen futures in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Global Environmental Change. 2020;61:102029. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature. 2017;525:367–384. doi: 10.1038/nature15371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson P, Lohse KA, Hall SJ. The globalization of nitrogen deposition: Consequences for terrestrial ecosystems. Ambio. 2002;32:113–119. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Muller-Karulis B, Carstenen J, Conley DJ, Conley DJ, Gustafsson BG, Andersen JH. Past, present and future eutrophication status of the Baltic Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankara AR, Daniel JS, Portmann RW. Nitrous oxide (N2O): The dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21 century. Science. 2009;326:123–125. doi: 10.1126/science.1176985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis S, Bekunda M, Howard CM, Karanja N, Winiwarter W, Yan X, Bleeker A, Sutton MA. Synthesis and review: Tackling the nitrogen management challenge: From global to local scales. Environmental Research Letters. 2016 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/120205EDITORIA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, Chapin FS, III, Lambin E, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, Nykvist B, de Wit CA, Hughes T, van der Leeuw S, Rodhe H, Snyder PK, Costanza R, Svedin U, Falkenmark M, Corell RW, Fabry VJ, Hansen J, Walker B, Liverman D, Richardson K, Crutzen P, Foley JA. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 2009;461:472–475. doi: 10.1038/461472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo TA, Tully K, Palm C, Neill C. Leaching losses from Kenyan maize cropland receiving different rates of nitrogen fertilizer. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 2017;108:195–209. doi: 10.1007/s10705-017-9852-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez PA. Properties and management of soils in the tropics. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez PA, Denning GL, Nziguheba G. The African green revolution moves forward. Food Security. 2009;1:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s12571-009-0011-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Howard CM, Erisman JW, Billen G, Bleeker A, Grennfelt P, Grinsven H, Grizzetti B, editors. The European nitrogen assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tomich TP, Brodt SB, Dahlgren RA, Snow KM, editors. The California nitrogen assessment: Challenges and solutions for people, agriculture, and the environment. Oakland, CA: Univ of Calif Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN Population Prospects. 2019. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=UN+Population+Prospects+2019.

- UNEP . Global environmental outlook 4 (GEO-4) Nairobi: United Nations Environ Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. 2019. Sustainable nitrogen management resolution. UNEP/EA.4/Res.14. United Nations Environ. Program, Nairobi.