Abstract

Endurance-sport athletes have a high incidence of gastrointestinal disorders, compromising performance and impacting overall health status. An increase in several proinflammatory cytokines and proteins (LPS, I-FABP, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, C-reactive protein) has been observed in ultramarathoners and triathlon athletes. One of the most common effects of this type of physical activity is the increase in intestinal permeability, known as leaky gut. The intestinal mucosa's degradation can be identified and analyzed by a series of molecular biomarkers, including the lactulose/rhamnose ratio, occludin and claudin (tight junctions), lipopolysaccharides, and I-FABP. Identifying the molecular mechanisms involved in the induction of leaky gut by physical exercise can assist in the determination of safe exercise thresholds for the preservation of the gastrointestinal tract. It was recently shown that 60 min of vigorous endurance training at 70% of the maximum work capacity led to the characteristic responses of leaky gut. It is believed that other factors may contribute to this effect, such as altitude, environmental temperature, fluid restriction, age and trainability. On the other hand, moderate physical training and dietary interventions such as probiotics and prebiotics can improve intestinal health and gut microbiota composition. This review seeks to discuss the molecular mechanisms involved in the intestinal mucosa's adaptation and response to exercise and discuss the role of the intestinal microbiota in mitigating these effects.

Keywords: leaky gut, exercise threshold, gastrointestinal disorder, gut microbiota, gut injury

Introduction

Physical exercise is a non-pharmacologic agent in preventing and managing non-communicable chronic diseases, where its beneficial effect is well-documented in the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems. In addition to these systems, physical exercise also promotes positive adaptations in the gastrointestinal tract, such as a decrease in colon cancer risk (1). However, exacerbated exposure to exercise stress and even moderate-intensity training (depending on volume, environment and age) may negatively impact the gastrointestinal environment, contributing to the worsening of other clinical conditions (2–4). In this context, the array of normal physiological responses to exercise that disturb and affect gastrointestinal integrity and function was dubbed “exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome,” estimated to present a 70% of the maximum work capacity prevalence among endurance athletes (3).

Exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome results from two distinct and communicable pathways: The circulatory-gastrointestinal pathway and the neuroendocrine-gastrointestinal pathway. The first pathway redistributes blood flow to working muscles and peripheral circulation, reducing total splanchnic perfusion, while the neuroendocrine-gastrointestinal pathway is related to the increase in sympathetic activation and the consequent reduction in the gastrointestinal functional capacity (5, 6). Thus, it is believed that intestinal ischemia is considered the leading cause of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (and bloody diarrhea), occurring 2-fold more in running athletes compared to other endurance sports (e.g., cycling or swimming), and 1.5–3 times more in elite athletes compared to amateurs (7). Nevertheless, both pathways lead to gastrointestinal symptoms with acute or chronic health complications (8).

Strenuous exercise's negative effects (≥60–70% VO2max) may not be limited to the gastrointestinal system and the intestinal microbiota, affecting its structure and functionality. Deterioration of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier may also occur, increasing its permeability to bacterial endotoxins, and low-grade systemic inflammation may not only affect gastrointestinal homeostasis but also overall health (9, 10). However, not every type of physical exercise negatively affects the gut microbiota; on the contrary, there is compelling evidence that exercise has positive effects on the colon, increasing the microbiota's diversity and increasing butyrate-producing bacteria as well as butyrate concentration (9).

Despite that, exercise varieties and their dynamics of intensity and volume have not yet been widely studied to establish the ideal dose-response ratio of exercise to its protective or restorative effect on the gastrointestinal tract (11). To this end, the present bibliographic review aimed to (1) report the molecular and physiological changes in intestinal permeability caused by exercise (2) describe whether it is currently possible to determine an exercise “threshold” to avoid the leaky gut phenomenon and the factors involved in this process and (3) mention the main factors that contribute to minimizing the occurrence of intestinal injury. For this, a search strategy was used focusing on exercise and intestinal permeability, as well as the factors that influence this process.

Search Strategy

The following search strategy was carried out by searching for full-text articles indexed in Pubmed. The terms used for the search were: “exercise AND intestinal permeability”; “exercise AND intestinal injury”; “exercise AND leaky gut”; “exercise AND gut microbiota.” All individual terms were used to assess related topics on exercise and intestinal permeability and the other factors that boost this relationship.

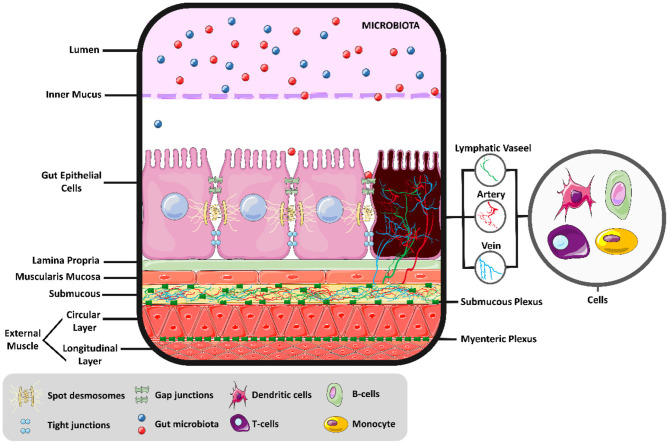

Gastrointestinal Physiological and Molecular Adaptations to Exercise

The intestinal environment is a complex of different cells, acting together to generate motility, digestion, absorption, and secretion, as shown in Figure 1. Above the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and in contact with the intestinal lumen, a mucus layer contains the intestinal microbiota, composed of trillions of microorganisms with metabolic, immunological, and physiological roles in symbiosis with the host. Different IECs exist in the intestine's innermost layer, such as enterocytes, Paneth cells, goblet cells, enterocytes, and microfold cells, each with a distinct function. In general, these cells protect the IECs by creating a barrier with narrow spaces between them and secreting mucus and various antimicrobial agents to defend the epithelial layer. In addition, a covering layer of connective tissue known as the lamina propria is responsible for establishing molecular communication between the microbiota and the immune cells. The last layer comprises smooth muscle, regulated by interstitial cells; this layer is responsible for intestinal motility (12). The myenteric and submucosal plexuses form the enteric nervous system and are responsible for regulating the local bloodstream and intestinal secretions (13). Thus, physiological responses to exercise are changes in a large group of cells (14), in addition to modulations in the intestinal microbiota (15).

Figure 1.

Intestinal molecular environment. Intestinal health and the permeability balance depend on the homeostasis of the intestinal environment.

It is well-known that physical exercise leads to an increase in the skeletal muscle's energy demand and the organism's adaptation to supply this demand. Through this stimulus, the sympathetic nervous system's activity alters hemodynamics, reducing and redistributing the blood flow from vital organs to the exercising muscles. It has been shown that the decrease in splanchnic blood flow occurs at around 70–80% of the maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) during exercise (5, 16). Thus, the type of exercise and its intensity can promote changes in the gastrointestinal system through its hypoxic effect.

Local intestinal ischemia is one of the main characteristics of vigorous endurance (17). This is one of the main physiological factors that cause cell damage and disorders, due to a reduction in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis in mitochondrial respiration (18, 19). Splanchnic hypoperfusion and subsequent ischemia can damage the specialized antimicrobial protein-secreting cells (Paneth cells), the mucus-producing cells (such as goblet cells), and the tight junction proteins (claudin and occludin) that prevent the infiltration of pathogenic organisms into the systemic circulation (8). Thus, endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and proinflammatory cytokines may pass through epithelial cells due to their permeability, an effect known as “leaky gut” (20, 21). This phenomenon may explain, in part, the impaired absorption of intestinal nutrients observed after strenuous exercise (22).

An increase in sympathetic system stimuli can also lead to subsequent alterations in intestinal motility and absorption capacity (8, 23). This malabsorption is observed in endurance running, and it is not yet known whether it is due to local ischemia or down-regulated intestinal transporter activity, or a combination of both (22, 24). Together, the above exercise-related responses are associated with lower-gastrointestinal symptoms such as flatulence, lower-abdominal bloating, urge to defecate, abdominal pain, abnormal defecation, such as diarrhea, and bloody stools (8, 14, 17, 22).

From a molecular perspective, the Caco-2 TJ permeability induced by the increase of IL-1β is regulated by synthesis and increased transcription of MLCK mRNA (25, 26). The IL-1β causes a rapid increase in mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1), and this plays an important role in the regulation of a variety of biological activities in intestinal epithelial cells (27). Further, the MLCK activation pathway appears to be an essential molecular issue in TJ regulation and intestinal permeability (26, 28, 29). Similarly, the increase in permeability occurs with the increase of tumor necrosis-alpha (TNF-α) (30). Thus, physical exercise can increase intestinal permeability due to the increased expression of these molecules caused by physiological changes in exercise.

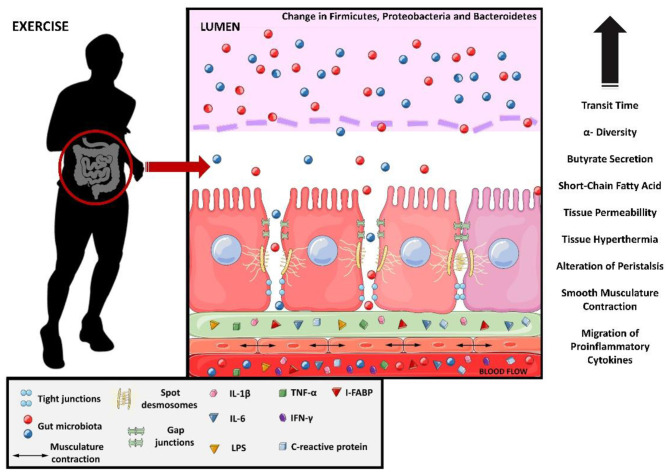

Strenuous exercise may affect the intestinal epithelial cells (31), tight junction (TJs) proteins (32), smooth muscle cells (33), and the composition and function of the gut microbiota (GM) (34), compromising gastrointestinal homeostasis. This phenomenon has been observed in ultramarathon athletes, where the profile of proinflammatory proteins and cytokines such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, TNF-α, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) increased (20). Similarly, LPS, IL-6, and C-reactive protein levels also increase in other types of ultra-endurance exercise (e.g., ~8 h of triathlon) (35). Apparently, the increase in intestinal permeability caused by strenuous exercise seems to coincide with the gut microbiota changes (36). The molecular and tissue changes in the intestine caused by exercise are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Molecular changes from exercise causing leaky gut. Interleukin 1 beta, IL-1B; interleukin 6, IL-6; lipopolysaccharides, LPS; tumor necrosis factor-alpha, TNF-alfa; interferon gamma, IFN-y and intestinal fatty-acid binding protein, I-FABP.

Strenuous exercise is also known to induce the synthesis of enterocyte-derived intestinal fatty-acid binding protein (I-FABP), an intestinal biomarker of enterocyte damage and ischemia (8). The increased release of I-FABP into circulation indicates damage to mature enterocytes, and is observed after prolonged exercises (≥1 h) and after shorter periods of resistance training (30 min) (8). Besides these factors, hyperthermia (>40°) and acute local ischemia are exercise-related factors that are known to disturb the tight junctions, increasing intestinal permeability (31, 32).

The increase in intestinal permeability also allows LPS to pass into the bloodstream. This increase in the concentration of LPS in the blood occurs in exercise with short duration (<20 min) (37), long (>1 h) duration (38, 39), and performed in a hot environment (40, 41). However, there is evidence that moderate exercise can decrease circulating LPS concentrations (42). These data show a similarity between the increases in circulating LPS and I-FABP, as well as the increase in proinflammatory cytokines.

After exploring the main molecular changes caused by exercise, the next topic aims to highlight whether it is possible to determine an exercise “threshold” that leads to the “leaky gut” phenomenon.

A Possible Exercise “Treshold” to Avoid Leaky Gut

While low-to-moderate intensity is associated with positive effects on the gastrointestinal tract, including mucosa preservation and improved intestinal motility, ischemia and hypoperfusion associated with strenuous exercise are commonly associated with reduced gastric motility, epithelial injury, disturbed mucosa integrity, enhanced permeability, impaired nutrient absorption, and endotoxemia with local and systemic low-grade inflammation (8) (Figure 2). It is therefore essential to identify the appropriate exercise dose-response or safe thresholds that do not generate these adverse effects or even act as a recovery agent for the intestinal mucosa.

Naturally, it should be noted that different exercise stimuli may lead to adverse impacts on the intestine, also considering their intensity and duration, and the environmental conditions in which they take place. It is known that high altitudes can have adverse effects on the small intestine (43, 44) and that high temperatures (hyperthermia) induced by intense exercise may lead to gut ischemia (45). Also, variations in physical training such as intensity, volume, continuity (alternation between increasing stresses and the proportional recovery period), training time (46) and fluid restriction during exercise are determinant factors that may contribute to leaky gut (8, 47, 48). Finally, the impact of exercise on the intestinal microbiota (IM) composition must be considered, as the IM is a crucial component for maintaining the gastrointestinal mucosa's integrity.

The increase in intestinal permeability has already been identified in several types of exercise: cycling (49), swimming (50), and running (51, 52). Although there is still no comparison between the types of exercise and the leaky gut, apparently the determining factors for the increase in permeability are the intensity and volume of training. The assessment of mucosal-injury induced by exercise is often done by a dual-sugar test with lactulose and rhamnose (L/R ratio's) or claudin-3 concentrations for analysis of the small intestine and the analysis of I-FABP concentration as an intestinal biomarker of epithelial injury (5), as shown in Table 1. These studies show that ≥70% of maximum working capacity and with a volume >1 h can lead to an increase in intestinal permeability. However, as shown in Table 1, several factors can increase or minimize the permeability: temperature, food during the training process, fluid restriction and training at different times of the day.

Table 1.

Changes in intestinal permeability caused by exercise and the influencing factors.

| Subjects | Exercise type | Exercise intensity | Exercise volume | Contribution influence factor | Minimization influence factor | Change in permeability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endurance trained M and W (n = 7) | Acute running | 70% of VO2max | 60 min | 30°C Tamb (12 to 20% RH) | At 20 min of exercise: 27 g of Cho | Increase in I-FABP by exercise and decreased hours after exercise in the Cho group | (53) |

| Recreationally trained M (n = 12) | Resistance-type exercise (combined cycling with a leg press) | Load progression of 40–55–70% between sets | 30 min | – | – | Increase in I-FABP by exercise | (54) |

| Competitive cyclists M and W (n = 13) | Acute cycling | 70% Wmax + Time trial | 45 min of 70% Wmax + 15 min of time trial | 7 days of gluten-containing diet | 7 days of gluten-free diet | Increase in I-FABP after 15 min time trial (no difference by diet) | (55) |

| Recreationally trained M (n = 8) | Acute running and cycling | Cycling at 50% HRR + running at 80% HRR + maximal-distance trial) + cycling at 50% HRR, respectively | 15 (cycling)-30 (running)-30 (maximal running)-15 min (cycling), respectively | 30°C Tamb (50% RH) | 1.7 g·kg−1·day−1 of bovine colostrum (COL) supplementation | Increase in I-FABP by exercise (no difference by diet). This increase was greater with 6 training sessions per wk than 3 sessions | (56) |

| Active runners (n = 20) | Running | 70% of VO2max | 60 min | – | – | Increase in I-FABP by exercise | (6) |

| cyclists and triathletes M (n = 9) | Acute cycling | 70% Wmax | 60 min | 400 mg ibuprofen intake before cycling | – | Increase in I-FABP by exercise and ibuprofen | (57) |

| Endurance trained M (n = 8) | 5 consecutive days of Running | 78% of VO2max (4 mMol/L blood lactate) until Tc increases 2.0°C or volitional exhaustion | Volitional exhaustion = 24 min | Tamb 40°C (40% RH) | – | Increase in I-FABP by exercise in the heat. This increase was decreased from the 1° to the 5° day of exercise | (41) |

| Well-trained athletes M (n = 16) | Acute cycling | 70% Wmax | 60 min | – | Acute ingestion of sodium nitrate (NIT; 800 mg NO3), sucrose (SUC; 40 g) or water (Placebo) | Increase in I-FABP by during exercise and post-exercise. I-FABP was attenuated in SUC vs. PLA | (49) |

| Endurance runners M and W (n = 25) | Running | 60% of VO2max | 2 h | – | Gel-disks containing 30 g carbohydrates (2:1 glucose-fructose, 10% w/v) every 20 min | Increase in I-FABP by exercise (no difference by supplementation) | (22) |

| Healthy M (n = 12) | Acute running | 70% of VO2peak | 60 min | – | 14 days of 20 g/day supplementation with bovine colostrum (Col) | Increase in I-FABP by exercise. I-FABP attenuated by Col supplementation post-exercise | (58) |

| Health M (n = 12) | Acute cycling | 70% of VO2max | 45 min | Tamb 30°C (40% RH) | Tamb 20°C (40% RH) | Increase in I-FABP by exercise (no difference by temperatures groups) | (59) |

| Endurance runners (n = 16) | Running | 60% of VO2max | 3 h | Training at night (21:00 h) | Training in the morning (09:00 h) | Increase in I-FABP by exercise (both trials). Night resulted in greater total-gastrointestinal symptoms | (46) |

| Active M and W (n = 15) | Running | 70% of VO2max | 60 min | Tamb 33°C (50% RH) | – | Increase in plasma claudin by exercise | (60) |

| Triathletes (n = 15) | Swimming, cycling, and mountain running | 1,500-m swimming, 36-km cycling, and 10-km mountain running | – | – | 0.7 ± 0.3 L of water and 1.5 ± 0.5 L of isotonic drinks | Increase in plasma zonulin by exercise | (50) |

| Active runners (n = 17) | Acute running | 80% of the speed of their best 10 km race time. | 90 min | Runners with history of experiencing GI symptoms during running (symptomatic group) | – | Increase of L/R ratios, I-FABP and zonulin after exercise. No difference between asymptomatic and symptomatic group | (51) |

| Endurance runners M and W (n = 7) | Running | 60% of VO2max | 3 x of 2 h | Tamb 35°C (50% RH) - Exertional heat stress (EHS) | 15 g glucose (GLUC) or energy-matched whey protein hydrolysate (WPH) | GLUC and WPH minimized I-FABP and L/R ratios | (61) |

| Trained runners M (n = 7) | High-intensity interval running | 120% of VO2max with 18 × 400 m interval efforts | Separated by 3 min of complete rest | – | – | Increase of L/R ratios and I-FABP after exercise | (52) |

| Healthy M (n = 12) | Running | 80% of VO2max | 20 min | – | 20 g/day bovine colostrum (14 days) | Increase of L/R ratios by exercise and attenuated by colostrum supplementation | (62) |

| M and W endurance runners (n = 20) | Running | 70% of VO2max | 60 min | Fluid restriction | 4% glucose solution | Increase of L/R ratios by exercise + fluid restriction | (47) |

| Active M and W (n = 6) | Running | 40–60–80% VO2peak | 60 min | – | – | Increase of L/R ratios by 80% VO2peak compared to other intensities | (48) |

| marathon runners M and W (n = 15) | Acute running | Road marathon competition | 2 h 43 min to 5 h 28 min | – | Vitamin E (1,000 IU daily) | Increase of L/R ratios by exercise (no difference by supplementation) | (63) |

| Soldiers M (n = 73) | 4-day cross-country ski march | 51 km cross-country ski-march while 139 carrying a ~45 kg pack | 50:10 min work-to-rest ratios | – | – | Increase of L/R ratios by exercise | (36) |

| Endurance trained M and W (n = 7) | Acute running | 65–70% of VO2max | 60 min | Tamb 30°C (12–20% RH) | Oral glutamine supplementation (0.9 g/kg) for 7 days | Increase of L/R ratios by exercise and decreased with glutamine supplementation | (64) |

I-FABP, intestinal fatty-acid binding protein; HRR, heart rate reserve; L/R ratios, Men, M; dual-sugar test with lactulose and rhamnose; Post-exercise (or peak) core temperature (Tc), RH, relative humidity; Tamb, ambient temperature; VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption, W, women; Wmax, watt maximum; wk, week.

It has been evidenced that 60 min of running exercise at an 80% VO2Peak leads to an enhanced lactulose/rhamnose ratio, compared to lower intensities of 40 and 60% of the VO2Peak (48). Furthermore, trained individuals submitted to a fluid restriction protocol (glucose or sweetened water) and 60 min of exercise at 70% of VO2max presented an enhanced lactulose/rhamnose ratio, indicating that dehydration may increase intestinal permeability (47). On the other hand, exercise-induced hyperthermia has been one of the leading hypotheses for increasing intestinal permeability and exercise-induced endotoxemia (65). Healthy people who trained for 60 min at 70% of the VO2max in hot environments [33°C, 50% relative humidity (rH)] and cold (22°C, 62% rH), led to the same alteration in intestinal permeability compared to control (same claudin-3 alterations). The hot environment group had a significant increase in blood LPS, indicating the effect of exercise-induced endotoxemia (60).

Similarly, 60 min of running and cycling at a moderate intensity led to an increased concentration of I-FABP (6, 55, 56), with the highest concentration seen in hot environments (30°C) (56). It was recently identified that 45 min of cycling at an intensity of 70% of VO2max at different temperatures (30° or 20°) raised I-FABP levels in a similar way (59). Thus, the effect of temperature and endurance training on I-FABP is still unclear, due to methodological differences in their analysis (53). Besides, several dietary interventions can influence I-FABP concentrations in the context of physical exercise (58, 62, 66). For example, sucrose supplementation may alleviate the concentration of circulating I-FABP elevated by exercise (49). Thus, great caution is needed when analyzing the relationship between physical exercise and serum levels of I-FABP to presume an intestinal injury.

Although the above studies have shown that 60 min at an intensity at 70% of VO2max are related to an increase in intestinal permeability, the athlete's training level must be considered. It has been previously reported that local ischemia and hyperthermia are the main factors for leaky gut. The progressive increase in catecholamines by vigorous endurance exercise is one of the main signs of this gastrointestinal ischemia (67). In this sense, catecholamine levels tend to rise above the lactate threshold, on average, in a range of 60–80% of VO2max, where lactate is accumulated. Endurance-trained, sprint-trained, and weightlifter-trained athletes tend to have higher catecholamine concentrations at rest than inactive subjects (68). Endurance athletes also tend to have a rise in post-exercise adrenaline concentrations comparable to untrained subjects, even working at the same relative training level (69). This suggests that local intestinal ischemia should still be investigated in groups with different levels of training.

After 30 min of local intestinal ischemia, the circulating concentration of the L/R ratio is increased, but after 120 min of reperfusion, there are no changes (70). I-FABP concentrations are observed to be similar at the same times. There is evidence that only 60 min of reperfusion is capable of resealing the epithelial barrier and that remnants of removed apoptotic epithelial cells have been observed in the lumen (71). An acute bout of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) (eighteen 400-m runs at 120% maximal oxygen uptake) can increase permeability (increase in L/R ratio's and I-FABP) despite not experiencing symptoms (52). However, although acute exercise generates an increase in permeability, it has been hypothesized that chronic training may enhance gut barrier integrity overall through several mechanisms (72). Thus, it is not known how much physical training can damage the intestine, and the comparison between the acute and chronic effects of training on the intestinal injury still needs to be explored.

Low-to-moderate exercise (30–60% of maximum oxygen consumption, VO2max) accelerates gastric emptying and may decrease the risk for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) (73). It was shown that moderate aerobic training improved gastrointestinal motility after 12 weeks of training (74), reducing transient stool time, which benefits the host by decreasing pathogens' contact with the gastrointestinal mucus layer (75). A similar effect on gut transit was observed after 1 week of running or cycling at a moderate intensity (50% of VO2max) (76). Even an acute bout of swimming exercise increased the ileum's contractile reactivity in an animal model (77). These observations demonstrate the intestinal mucosa's sensitivity to physical exercise and its most diverse manifestations; however, exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome has been more associated with strenuous exercise.

The studies revealed that variations in the intensity, volume, and/or training time of exercise training make it difficult to unify the relationship between physical training and leaky gut. There is some evidence that vigorous endurance training (≥60 min and ≥70% of maximum work capacity) may lead to injury and increased intestinal permeability. Depending on variables such as temperature, moderate to prolonged exercise (>60 min) can also lead to intestinal injury, based on elevations in the circulating I-FABP (56). It is still uncertain what the acute and chronic effects of exercise are on intestinal injury. Moreover, high altitude and dehydration also increase intestinal damage and intestinal permeability. It is worth mentioning that exercise performed above 70% of the maximum work capacity can generate benefits in other organs, such as a greater and faster increase in VO2max or a greater decrease in total fat mass (78, 79). Thus, it is difficult to determine a “threshold” of exercise to avoid leaky gut. Although intensities over ≥70% of maximum work capacity and a duration of ≥60 min is an approximate parameter, several variables can act in the intestinal environment, and this possible “threshold” becomes variable. Therefore, the emergence of new studies with a focus on determining the “threshold” is extremely important for active people to have a safe training parameter aimed at intestinal health.

Exercise as a Restorative Agent of the Gastrointestinal Environment

The gut microbiota's responsiveness to external factors has received much attention in recent years due to these changes' clinical potential effects on the host's health. Among these factors, dietary intervention and physical exercise are recurrent elements in studies involving the GM's composition and its systemic impacts across different tissues and physiologic systems (80). Naturally, adequate eating habits and physical activity are two external factors that receive much attention from the scientific community due to their role in preventing diseases and maintaining health (81).

As previously described, prolonged and excessive exercise stimuli may affect the gastrointestinal environment, impacting the mucosa's integrity and increasing its permeability to external agents such as endotoxins. This process is associated with the onset of proinflammatory signaling, affecting gastrointestinal health. Dehydration, bloody diarrhea episodes, and abdominal discomfort are typical responses in endurance athletes (17). These effects are also expected to compromise sports performance and affect overall health (39, 82). As a result, several strategies have been considered to restore the gastrointestinal mucosa by modulating the gut microbiota. To date, the mutual interaction among exercise, dietary supplementation, and gut microbiota is speculated to be a key strategy to reduce the effects of gastrointestinal distress caused by strenuous exercise and even a game-changer concerning sports performance.

Unlike what is observed in response to strenuous exercise stimuli, certain intensities positively modify the GM's quality and function, favoring the host's health. In this way, a body of evidence has shown that exercise is a potent modulator of intestinal microbiota composition and function, leading to enrichment and bacterial proliferation, improvement of intestinal barrier integrity, and the synthesis of immunomodulatory and antimicrobial agents (83). Moderate endurance exercise has been associated with preserving the intestinal mucosa and the upregulation of β-defensin 1, α-defensin 5, regenerating gene Type IIIb (Reg IIIb), and Reg IIIc (84). The defensins and the Reg 3 family are proteins with antimicrobial actions that act as barriers, protecting body surfaces against microorganisms (85, 86). This exercise intensity was also shown to reduce irritable bowel syndrome (80) effectively, which is a condition often observed and underdiagnosed in endurance athletes (87).

Recent research on the GM's response to exercise, especially endurance, has shed light on the cross-talk between skeletal muscle and the GM, and its influence on muscle bioenergetics. In the gastrointestinal tract, some of these effects include the proliferation and stimuli of intestinal microbes and the synthesis of microbe-metabolites (88). Among these metabolites, the short-chain fatty acids (formate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate) significantly impact human metabolism and protect the gut mucosa (89). In this matter, an injection of gastric and intestinal SCFAs can lead to increased mRNA abundance of Occludin and Claudin-1 (TJs), decreasing the mRNA and protein abundances of IL-1β in the colon, and diminishing infiltration of neutrophils to the gut lamina propria (90, 91). Thus, the hypothesis arises that exercise changes may increase SCFAs, similarly to the direct injection of these metabolites.

Studies with humans have shown that cardiovascular capacity is positively correlated with increased bacterial diversity and SCFAs producing bacteria (92). However, some of these effects might depend on body composition (93). In this study, endurance exercise altered the gut microbiota in lean and obese subjects; however, the production of microbe-SCFAs (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) was enhanced only in the lean group. Together, these studies establish new clinical perspectives for manipulating the GM and novel insights on the cross-talk between gut microbes and their metabolites and the skeletal muscle, especially concerning the host metabolism and exercise capacity regulation.

The GM interacts with the intestinal immune function by activating G protein-coupled receptor (GPR41 and GPR43) and histone activation deacetylases (HDAC) in leucocyte endothelial cells. SCFAs can bind to Gpr43 (SCFA-Gpr43 signaling) and reduce inflammatory responses of neutrophils and eosinophils and be capable of inhibiting HDAC, preventing colorectal cancer (94, 95). In this context, moderate-to-vigorous physical training for only 6 weeks can increase fecal SCFAs and possibly activate the molecular pathways mentioned above, although these pathways have not yet been clinically explored in the context of exercise (93). This is one explanation for why exercise can prevent and treat colorectal cancer (1, 96).

The transplantation of fecal microbiota containing Veillonella atypica isolated from a marathon runner was shown to increase the submaximal running time to exhaustion on mice. Considering that Veillonella atypica metabolizes lactate into propionate and acetate through the methyl malonyl-CoA pathway, it is speculated that the lactate produced during exercise is converted into SCFAs, improving exercise capacity (88). Moreover, several probiotic supplements can decrease intestinal damage caused by strenuous training (97–99), as shown in Table 1. The probiotics Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (100), UCC118 (99) and bovine colostrum (98), in addition to different dietary applications (61, 101, 102) seem to exert this softening effect on the permeability caused by strenuous exercise.

Intestinal epithelial barrier properties are also maintained by cellular junctions called desmosomes, shown in Figure 1. The only desmosome expressed in enterocytes (Desmoglein 2, Dsg2) is activated under the same conditions as p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38 MAPK) (103, 104). Although there is still no study showing the effects of exercise on Dsg2 of enterocytes, it is known that physical training can activate p38 MAPK in different muscles (105, 106).

If, on the one hand, intestinal dysbiosis is associated with a quantitative and qualitative reduction of the intestinal microbes, on the other hand, exercise at specific doses may be a key strategy to restore the composition and function of the gut microbiota, improving gastrointestinal mucosa and reducing inflammatory signaling. It may also operate an intricate process of bidirectional communication with the skeletal muscle metabolism (83).

Conclusion

Physical exercise acts as a modulator of the intestinal environment due to the demands of skeletal muscle. Strenuous exercise leads to higher gastrointestinal ischemia and hyperthermia. So far, it is believed that vigorous endurance training with ≥60 min at ≥70% of the maximum work capacity increases the intestinal permeability, with an enhanced effect observed in hot environments, at high altitude, and under dehydration. In response to strenuous exercise, leaky gut is associated with increased I-FABP and infiltration of bacterial endotoxins within the blood circulation. On the other hand, non-prolonged moderate exercise may preserve the intestinal mucosa by accelerating gastric emptying, improving intestinal motility, increasing the abundance and diversity of the gut microbiota, also increasing butyrate-producing bacteria and the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids. However, to date, an exercise “threshold” that may lead to increased gut permeability is still uncertain.

The determination of a “threshold” is essential for the intestinal health of individuals who are athletes or who seek to be active. It is necessary to standardize the analyses that indicate the leaky gut. After that, it is advisable to carry out research that analyzes these factors (I-FABP, sugar test, LPS, among others) with a progression of intensities and volumes of exercise. Obviously, confounding factors such as temperature, altitude, dehydration and degree of trainability need to be controlled for. Thus, more studies are needed in order to emphasize the role of exercise in intestinal permeability and to pinpoint other variables that may influence this phenomenon at the time of activity.

Author Contributions

FR, BP, and GM: writing of the manuscript and elaboration of the figures. LHK: writing of the manuscript. OF: writing of the manuscript and general review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by CNPq (437308/2018-9), CAPES, FUNDECT e FAPDF.

References

- 1.Oruc Z, Kaplan MA. Effect of exercise on colorectal cancer prevention and treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. (2019) 11:348–66. 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i5.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ter Steege RW, Van der Palen J, Kolkman JJ. Prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints in runners competing in a long-distance run: an internet-based observational study in 1281 subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2008) 43:1477–82. 10.1080/00365520802321170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ter Steege RW, Kolkman JJ. Review article: the pathophysiology and management of gastrointestinal symptoms during physical exercise, and the role of splanchnic blood flow. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2012) 35:516–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenney WL, Ho CW. Age alters regional distribution of blood flow during moderate-intensity exercise. J Appl Physiol. (1985) 79:1112–9. 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Wijck K, Lenaerts K, Grootjans J, Wijnands KA, Poeze M, Van Loon LJ, et al. Physiology A and pathophysiology of splanchnic hypoperfusion and intestinal injury during exercise: strategies for evaluation and prevention. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2012) 303:G155–68. 10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Wijck K, Lenaerts K, Van Loon LJ, Peters WH, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e22366. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Oliveira EP, Burini RC, Jeukendrup A. Gastrointestinal complaints during exercise: prevalence, etiology, nutritional recommendations. Sports Med. (2014) 44(Suppl. 1):S79–85. 10.1007/s40279-014-0153-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa RJS, Snipe RMJ, Kitic CM, Gibson PR. Systematic review: exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome-implications for health and intestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 46:246–65. 10.1111/apt.14157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gubert C, Kong G, Renoir T, Hannan AJ. Exercise, diet and stress as modulators of gut microbiota: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. (2020) 134:104621. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Iglesias P, Estruel-Amades S, Camps-Bossacoma M, Massot-Cladera M, Castell M, Perez-Cano FJ. Alterations in the mucosal immune system by a chronic exhausting exercise in Wistar rats. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:17950. 10.1038/s41598-020-74837-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohr AE, Jager R, Carpenter KC, Kerksick CM, Purpura M, Townsend JR, et al. The athletic gut microbiota. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2020) 17:24. 10.1186/s12970-020-00353-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders KM, Kito Y, Hwang SJ, Ward SM. Regulation of gastrointestinal smooth muscle function by interstitial cells. Physiology. (2016) 31:316–26. 10.1152/physiol.00006.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavin JB, Cuddihey H, MacNaughton WK, Sharkey KA. Acute regulation of intestinal ion transport and permeability in response to luminal nutrients: the role of the enteric nervous system. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2020) 318:G254–64. 10.1152/ajpgi.00186.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Nieuwenhoven MA, Brouns F, Brummer RJ. The effect of physical exercise on parameters of gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (1999) 11:431–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1999.00169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mailing LJ, Allen JM, Buford TW, Fields CJ, Woods JA. Exercise and the gut microbiome: a review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications for human health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. (2019) 47:75–85. 10.1249/JES.0000000000000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey E, Mistry DJ, MacKnight JM. Training room management of medical conditions: sports gastroenterology. Clin Sports Med. (2005) 24:525–40, viii. 10.1016/j.csm.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira EP, Burini RC. The impact of physical exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. (2009) 12:533–8. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832e6776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King DR, Padget RL, Perry J, Hoeker G, Smyth JW, Brown DA, et al. Elevated perfusate [Na(+)] increases contractile dysfunction during ischemia and reperfusion. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:17289. 10.1038/s41598-020-74069-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu F, Lu J, Manaenko A, Tang J, Hu Q. Mitochondria in ischemic stroke: new insight and implications. Aging Dis. (2018) 9:924–37. 10.14336/AD.2017.1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill SK, Teixeira A, Rama L, Prestes J, Rosado F, Hankey J, et al. Circulatory endotoxin concentration and cytokine profile in response to exertional-heat stress during a multi-stage ultra-marathon competition. Exerc Immunol Rev. (2015) 21:114–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart AS, Pratt-Phillips S, Gonzalez LM. Alterations in intestinal permeability: the role of the “leaky gut” in health and disease. J Equine Vet Sci. (2017) 52:10–22. 10.1016/j.jevs.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa RJS, Miall A, Khoo A, Rauch C, Snipe R, Camoes-Costa V, et al. Gut-training: the impact of two weeks repetitive gut-challenge during exercise on gastrointestinal status, glucose availability, fuel kinetics, running performance. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2017) 42:547–57. 10.1139/apnm-2016-0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill SK, Hankey J, Wright A, Marczak S, Hemming K, Allerton DM, et al. The impact of a 24-h ultra-marathon on circulatory endotoxin and cytokine profile. Int J Sports Med. (2015) 36:688–95. 10.1055/s-0034-1398535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa RJ, Snipe R, Camoes-Costa V, Scheer V, Murray A. The impact of gastrointestinal symptoms and dermatological injuries on nutritional intake and hydration status during ultramarathon events. Sports Med Open. (2016) 2:16. 10.1186/s40798-015-0041-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Dokladny K, Ma TY. Mechanism of IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J Immunol. (2008) 180:5653–61. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin Y, Blikslager AT. The regulation of intestinal mucosal barrier by myosin light chain kinase/rho kinases. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:3550. 10.3390/ijms21103550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Said HM, Ma TY. IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability is mediated by MEKK-1 activation of canonical NF-kappaB pathway. Am J Pathol. (2010) 177:2310–22. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D, Kerner R, Mrsny RJ, et al. Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. (1997) 273:C1378–85. 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham KE, Turner JR. Myosin light chain kinase: pulling the strings of epithelial tight junction function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2012) 1258:34–42. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06526.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Sadi R, Guo S, Ye D, Ma TY. TNF-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier is regulated by ERK1/2 activation of Elk-1. Am J Pathol. (2013) 183:1871–84. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dokladny K, Zuhl MN, Moseley PL. Intestinal epithelial barrier function and tight junction proteins with heat and exercise. J Appl Physiol 1985. (2016) 120:692–701. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00536.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuhl M, Schneider S, Lanphere K, Conn C, Dokladny K, Moseley P. Exercise regulation of intestinal tight junction proteins. Br J Sports Med. (2014) 48:980–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Lira CA, Vancini RL, Ihara SS, da Silva AC, Aboulafia J, Nouailhetas VL. Aerobic exercise affects C57BL/6 murine intestinal contractile function. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2008) 103:215–23. 10.1007/s00421-008-0689-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell CM, Davy BM, Hulver MW, Neilson AP, Bennett BJ, Davy KP. Does exercise alter gut microbial composition? A systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2019) 51:160–7. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeukendrup AE, Vet-Joop K, Sturk A, Stegen JH, Senden J, Saris WH, et al. Relationship between gastro-intestinal complaints and endotoxaemia, cytokine release and the acute-phase reaction during and after a long-distance triathlon in highly trained men. Clin Sci. (2000) 98:47–55. 10.1042/cs0980047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karl JP, Margolis LM, Madslien EH, Murphy NE, Castellani JW, Gundersen Y, et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota composition and metabolism coincide with increased intestinal permeability in young adults under prolonged physiological stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2017) 312:G559–71. 10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashton T, Young IS, Davison GW, Rowlands CC, McEneny J, Van Blerk C. Exercise-induced endotoxemia: the effect of ascorbic acid supplementation. Free Radic Biol Med. (2003) 35:284–91. 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00309-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosenberg AT, Brock-Utne JG, Gaffin SL, Wells MT, Blake GT. Strenuous exercise causes systemic endotoxemia. J Appl Physiol. (1988) 65:106–8. 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brock-Utne JG, Gaffin SL, Wells MT, Gathiram P, Sohar E, James MF, et al. Endotoxaemia in exhausted runners after a long-distance race. S Afr Med J. (1988) 73:533–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selkirk GA, McLellan TM, Wright HE, Rhind SG. Mild endotoxemia, NF-kappaB translocation, and cytokine increase during exertional heat stress in trained and untrained individuals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2008) 295:R611–23. 10.1152/ajpregu.00917.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barberio MD, Elmer DJ, Laird RH, Lee KA, Gladden B, Pascoe DD. Systemic LPS and inflammatory response during consecutive days of exercise in heat. Int J Sports Med. (2015) 36:262–70. 10.1055/s-0034-1389904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasawara KT, Cotechini T, Macdonald-Goodfellow SK, Surita FGE, Pinto SJL, Tayade C, et al. Moderate exercise attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and associated maternal and fetal morbidities in pregnant rats. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0154405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, Han T, Zhang W, Li W, Hu Y, Lee SK. Simulated altitude exercise training damages small intestinal mucosa barrier in the rats. J Exerc Rehabil. (2018) 14:341–8. 10.12965/jer.1835128.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Machado P, Caris A, Santos S, Silva E, Oyama L, Tufik S, et al. Moderate exercise increases endotoxin concentration in hypoxia but not in normoxia: a controlled clinical trial. Medicine. (2017) 96:e5504. 10.1097/MD.0000000000005504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joyner MJ, Casey DP. Regulation of increased blood flow (hyperemia) to muscles during exercise: a hierarchy of competing physiological needs. Physiol Rev. (2015) 95:549–601. 10.1152/physrev.00035.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaskell SK, Rauch CE, Parr A, Costa RJS. Diurnal versus nocturnal exercise-impact on the gastrointestinal tract. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2020). 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambert GP, Lang J, Bull A, Pfeifer PC, Eckerson J, Moore G, et al. Fluid restriction during running increases GI permeability. Int J Sports Med. (2008) 29:194–8. 10.1055/s-2007-965163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pals KL, Chang RT, Ryan AJ, Gisolfi CV. Effect of running intensity on intestinal permeability. J Appl Physiol 1985. (1997) 82:571–6. 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.2.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonvik KL, Lenaerts K, Smeets JSJ, Kolkman JJ, Van Loon LJ, Verdijk LB. Sucrose but not nitrate ingestion reduces strenuous cycling-induced intestinal injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2019) 51:436–44. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tota L, Piotrowska A, Palka T, Morawska M, Mikulakova W, Mucha D, et al. Muscle and intestinal damage in triathletes. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0210651. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karhu E, Forsgard RA, Alanko L, Alfthan H, Pussinen P, Hamalainen E, et al. Exercise and gastrointestinal symptoms: running-induced changes in intestinal permeability and markers of gastrointestinal function in asymptomatic and symptomatic runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2017) 117:2519–26. 10.1007/s00421-017-3739-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pugh JN, Impey SG, Doran DA, Fleming SC, Morton JP, Close GL. Acute high-intensity interval running increases markers of gastrointestinal damage and permeability but not gastrointestinal symptoms. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2017) 42:941–7. 10.1139/apnm-2016-0646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sessions J, Bourbeau K, Rosinski M, Szczygiel T, Nelson R, Sharma N, et al. Carbohydrate gel ingestion during running in the heat on markers of gastrointestinal distress. Eur J Sport Sci. (2016) 16:1064–72. 10.1080/17461391.2016.1140231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Wijck K, Pennings B, van Bijnen AA, Senden JM, Buurman WA, Dejong CH, et al. Dietary protein digestion and absorption are impaired during acute postexercise recovery in young men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2013) 304:R356–61. 10.1152/ajpregu.00294.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lis D, Stellingwerff T, Kitic CM, Ahuja KD, Fell J. No effects of a short-term gluten-free diet on performance in nonceliac athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2015) 47:2563–70. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morrison SA, Cheung SS, Cotter JD. Bovine colostrum, training status, and gastrointestinal permeability during exercise in the heat: a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2014) 39:1070–82. 10.1139/apnm-2013-0583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Wijck K, Lenaerts K, Van Bijnen AA, Boonen B, Van Loon LJ, Dejong CH, et al. Aggravation of exercise-induced intestinal injury by ibuprofen in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2012) 44:2257–62. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318265dd3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.March DS, Jones AW, Thatcher R, Davison G. The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on intestinal injury and circulating intestinal bacterial DNA following exercise in the heat. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:1441–51. 10.1007/s00394-018-1670-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheahen BL, Fell JW, Zadow EK, Hartley TF, Kitic CM. Intestinal damage following short-duration exercise at the same relative intensity is similar in temperate and hot environments. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2018) 43:1314–20. 10.1139/apnm-2018-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeh YJ, Law LY, Lim CL. Gastrointestinal response and endotoxemia during intense exercise in hot and cool environments. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2013) 113:1575–83. 10.1007/s00421-013-2587-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snipe RMJ, Khoo A, Kitic CM, Gibson PR, Costa RJS. Carbohydrate and protein intake during exertional heat stress ameliorates intestinal epithelial injury and small intestine permeability. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2017) 42:1283–92. 10.1139/apnm-2017-0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marchbank T, Davison G, Oakes JR, Ghatei MA, Patterson M, Moyer MP, et al. The nutriceutical bovine colostrum truncates the increase in gut permeability caused by heavy exercise in athletes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2011) 300:G477–84. 10.1152/ajpgi.00281.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchman AL, Killip D, Ou CN, Rognerud CL, Pownall H, Dennis K, et al. Short-term vitamin E supplementation before marathon running: a placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. (1999) 15:278–83. 10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuhl MN, Lanphere KR, Kravitz L, Mermier CM, Schneider S, Dokladny K, et al. Effects of oral glutamine supplementation on exercise-induced gastrointestinal permeability and tight junction protein expression. J Appl Physiol 1985. (2014) 116:183–91. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00646.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swancoff AJ, Costa RJ, Gill S, Hankey J, Scheer V, Murray A, et al. Compromised energy and macronutrient intake of ultra-endurance runners during a multi-stage ultra-marathon conducted in a hot ambient environment. Int J Sports Sci. (2012)3:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma S, Tominaga T, Kanda K, Sugama K, Omae C, Hashimoto S, et al. Effects of an 8-week protein supplementation regimen with hyperimmunized cow milk on exercise-induced organ damage and inflammation in male runners: a randomized, placebo controlled, cross-over study. Biomedicines. (2020) 8:51. 10.3390/biomedicines8030051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kruk J, Kotarska K, Aboul-Enein BH. Physical exercise and catecholamines response: benefits and health risk: possible mechanisms. Free Radic Res. (2020) 54:105–25. 10.1080/10715762.2020.1726343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zouhal H, Jacob C, Delamarche P, Gratas-Delamarche A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med. (2008) 38:401–23. 10.2165/00007256-200838050-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kjaer M, Farrell PA, Christensen NJ, Galbo H. Increased epinephrine response and inaccurate glucoregulation in exercising athletes. J Appl Physiol 1985. (1986) 61:1693–700. 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.5.1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schellekens DH, Hundscheid IH, Leenarts CA, Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Buurman WA, et al. Human small intestine is capable of restoring barrier function after short ischemic periods. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:8452–64. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruine AP, van Bijnen AA, Heineman E, van Dam RM, et al. Rapid reversal of human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion induced damage by shedding of injured enterocytes and reepithelialisation. PLoS ONE. (2008) 3:e3428. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keirns BH, Koemel NA, Sciarrillo CM, Anderson KL, Emerson SR. Exercise and intestinal permeability: another form of exercise-induced hormesis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2020) 319:G512–8. 10.1152/ajpgi.00232.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neufer PD, Young AJ, Sawka MN. Gastric emptying during walking and running: effects of varied exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. (1989) 58:440–5. 10.1007/BF00643522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim YS, Song BK, Oh JS, Woo SS. Aerobic exercise improves gastrointestinal motility in psychiatric inpatients. World J Gastroenterol. (2014) 20:10577–84. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song BK, Kim YS, Kim HS, Oh JW, Lee O, Kim JS. Combined exercise improves gastrointestinal motility in psychiatric in patients. World J Clin Cases. (2018) 6:207–13. 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oettle GJ. Effect of moderate exercise on bowel habit. Gut. (1991) 32:941–4. 10.1136/gut.32.8.941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Araujo LC, de Souza IL, Vasconcelos LH, Brito Ade F, Queiroga FR, Silva AS, et al. Acute aerobic swimming exercise induces distinct effects in the contractile reactivity of rat ileum to KCl and carbachol. Front Physiol. (2016) 7:103. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sultana RN, Sabag A, Keating SE, Johnson NA. The effect of low-volume high-intensity interval training on body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2019) 49:1687–721. 10.1007/s40279-019-01167-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith-Ryan AE, Trexler ET, Wingfield HL, Blue MN. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight/obese women. J Sports Sci. (2016) 34:2038–46. 10.1080/02640414.2016.1149609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Donati Zeppa S, Agostini D, Gervasi M, Annibalini G, Amatori S, Ferrini F, et al. Mutual interactions among exercise, sport supplements and microbiota. Nutrients. (2019) 12:17. 10.3390/nu12010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fiuza-Luces C, Garatachea N, Berger NA, Lucia A. Exercise is the real polypill. Physiology. (2013) 28:330–58. 10.1152/physiol.00019.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oktedalen O, Lunde OC, Opstad PK, Aabakken L, Kvernebo K. Changes in the gastrointestinal mucosa after long-distance running. Scand J Gastroenterol. (1992) 27:270–4. 10.3109/00365529209000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hawley JA. Microbiota and muscle highway - two way traffic. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2020) 16:71–72. 10.1038/s41574-019-0291-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luo B, Xiang D, Nieman DC, Chen P. The effects of moderate exercise on chronic stress-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and antimicrobial defense. Brain Behav Immun. (2014) 39:99–106. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cobo ER, Chadee K. Antimicrobial human beta-defensins in the colon and their role in infectious and non-infectious diseases. Pathogens. (2013) 2:177–92. 10.3390/pathogens2010177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shin JH, Seeley RJ. Reg3 proteins as gut hormones? Endocrinology. (2019) 160:1506–14. 10.1210/en.2019-00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Killian LA, Lee SY. Irritable bowel syndrome is underdiagnosed and ineffectively managed among endurance athletes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2019) 44:1329–38. 10.1139/apnm-2019-0261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scheiman J, Luber JM, Chavkin TA, MacDonald T, Tung A, Pham LD, et al. Meta-omics analysis of elite athletes identifies a performance-enhancing microbe that functions via lactate metabolism. Nat Med. (2019) 25:1104–9. 10.1038/s41591-019-0485-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. (2016) 7:189–200. 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Diao H, Jiao AR, Yu B, Mao XB, Chen DW. Gastric infusion of short-chain fatty acids can improve intestinal barrier function in weaned piglets. Genes Nutr. (2019) 14:4. 10.1186/s12263-019-0626-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Salomão AB, Nochi RJ, Jr, Nascimento M, Neves JD, et al. Intraluminal injection of short chain fatty acids diminishes intestinal mucosa injury in experimental ischemia-reperfusion. Acta Cir Bras. (2006) 21:21–5. 10.1590/S0102-86502006000100006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moraes AC, Silva IT, Almeida-Pititto B, Ferreira SR. Intestinal microbiota and cardiometabolic risk: mechanisms and diet modulation. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. (2014) 58:317–27. 10.1590/0004-2730000002940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Allen JM, Mailing LJ, Niemiro GM, Moore R, Cook MD, White BA, et al. Exercise alters gut microbiota composition and function in lean and obese humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2018) 50:747–57. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Waldecker M, Kautenburger T, Daumann H, Busch C, Schrenk D. Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity by short-chain fatty acids and some polyphenol metabolites formed in the colon. J Nutr Biochem. (2008) 19:587–93. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bermon S, Petriz B, Kajeniene A, Prestes J, Castell L, Franco OL. The microbiota: an exercise immunology perspective. Exerc Immunol Rev. (2015) 21:70–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wong JN, McAuley E, Trinh L. Physical activity programming and counseling preferences among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2018) 15:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.March DS, Marchbank T, Playford RJ, Jones AW, Thatcher R, Davison G. Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein and gut permeability responses to exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2017) 117:931–41. 10.1007/s00421-017-3582-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davison G, Marchbank T, March DS, Thatcher R, Playford RJ. Zinc carnosine works with bovine colostrum in truncating heavy exercise-induced increase in gut permeability in healthy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. (2016) 104:526–36. 10.3945/ajcn.116.134403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Axelrod CL, Brennan CJ, Cresci G, Paul D, Hull M, Fealy CE, et al. UCC118 supplementation reduces exercise-induced gastrointestinal permeability and remodels the gut microbiome in healthy humans. Physiol Rep. (2019) 7:e14276. 10.14814/phy2.14276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mooren FC, Maleki BH, Pilat C, Ringseis R, Eder K, Teschler M, et al. Effects of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 on exercise-induced disruption of gastrointestinal integrity. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2020) 120:1591–599. 10.1007/s00421-020-04382-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gaskell SK, Taylor B, Muir J, Costa RJS. Impact of 24-h high and low fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharide, and polyol diets on markers of exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome in response to exertional heat stress. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2020) 45:569–80. 10.1139/apnm-2019-0187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marsh, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. (2016) 55:897–906. 10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ungewiss H, Vielmuth F, Suzuki ST, Maiser A, Harz H, Leonhardt H, et al. Desmoglein 2 regulates the intestinal epithelial barrier via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:6329. 10.1038/s41598-017-06713-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schlegel N, Meir M, Heupel WM, Holthofer B, Leube RE, Waschke J. Desmoglein 2-mediated adhesion is required for intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2010) 298:G774–83. 10.1152/ajpgi.00239.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Combes, Dekerle J, Webborn N, Watt P, Bougault V, Daussin FN. Exercise-induced metabolic fluctuations influence AMPK, p38-MAPK and CaMKII phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep. (2015) 3:e12462. 10.14814/phy2.12462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ludlow AT, Gratidao L, Ludlow LW, Spangenburg EE, Roth SM. Acute exercise activates p38 MAPK and increases the expression of telomere-protective genes in cardiac muscle. Exp Physiol. (2017) 102:397–410. 10.1113/EP086189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]