Abstract

The outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2019, have highlighted the concerns about the lack of potential vaccines or antivirals approved for inhibition of CoVs infection. SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is almost preserved across different viral species can be a potential target for development of antiviral drugs, including nucleoside analogues (NA). However, ExoN proofreading activity of CoVs leads to their protection from several NAs. Therefore, potential platforms based on the development of efficient NAs with broad-spectrum efficacy against human CoVs should be explored. This study was then aimed to present an overview on the development of NAs-based drug repurposing for targeting SARS-CoV-2 RdRp by computational analysis. Afterwards, the clinical development of some NAs including Favipiravir, Sofosbuvir, Ribavirin, Tenofovir, and Remdesivir as potential inhibitors of RdRp, were surveyed. Overall, exploring broad-spectrum NAs as promising inhibitors of RdRp may provide useful information about the identification of potential antiviral repurposed drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Nucleoside analogue, Antiviral, Drug

1. Introduction

Recent novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), are continuously killing people worldwide [1,2]. The incubation period for CoV disease-2019 (COVID-19) is between 2 and 14 days and transmission of the disease from one person to another is caused by the respiratory drops of cough and sneezing of people with this disease [[3], [4], [5]].

The most common symptoms of this disease are fever, cough and muscle weakness, and fatigue [[5], [6], [7]]. Uncommon symptoms include headache, runny nose, sore throat, hemoptysis, diarrhea, loss of taste or smell, and acute respiratory failure [8,9]. Some therapeutic approaches such as oxygen therapy, respiratory support, mechanical ventilation, proper nutrition, and prevention of pulmonary embolism can be used as supportive medical treatments for COVID-19 patients [10,11]. In cases of severe infections, supportive therapies such as antiviral drugs and inflammatory cytokines as well as immune system modulator drugs can be used for patients [12,13]. For example, the United States National Institutes of Health list several antiviral drugs which may be used to treat COVID-19 including Remdesivir, Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Ivermectin.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has not yet approved the specific antiviral treatment for COVID-19, but according to past experience, the use of antiviral drugs has attracted a great deal of attention in development of promising therapeutic platforms against this disease [[14], [15], [16]]. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration has approved the antiviral drug Veklury (Remdesivir) for treating COVID-19 patients. The introduction of antiviral drugs can dramatically increase the lifespan of people living with SARS-CoV-2 and reduce its associated mortality [17,18]. However, the treatment process may be failed due to the adverse effects of treatment regimens, and the longevity of the SARS-CoV-2 treatment process [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle consists of several stages, many of which have been successfully used as targets for the development of antiviral drugs [17]. Currently, the focus of the world is on finding a therapeutic approach for treatment of COVID-19.

As the first country to host the virus, China began researching the SARS-CoV-2 from the beginning [24,25]. On the other hand, the most powerful independent computer system in the world (SUMMIT) has been able to identify elements or compounds that can prevent the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak [26]. Researchers have also run thousands of programs on a computer to determine which compounds can effectively prevent the body's cells from becoming infected with the SARS-CoV-2 [27]. In the course of this analysis, SUMMIT evaluated what compounds could interact with the main biological macromolecules of SARS-CoV-2 and thus preventing its interaction with cells [27].

What is certain is that efforts are underway to ensure different strategies to treat and mitigate the damage of COVID-19 including vaccination and antiviral therapy. Advances in development of antiviral drugs will dramatically change the fate of COVID-19 infection from a risky disease to a controllable chronic infection [14,16,28]. In the near future, developed antiviral drugs will show higher potential and greater tolerability than conventional drugs. Some detailed knowledge about the potential of medications and diets, toxicity, drug interactions, and drug resistance will help physicians choose the most appropriate treatment regimen for particular patients with different underlying medical conditions [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33]].

2. Different classes of inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2

Different classes of inhibitors can be developed for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These classes include enzyme inhibitors (including protease, polymerase, methyltransferase (MTase) and exonuclease inhibitors), receptor inhibitors and viral fusion inhibitors [[34], [35], [36]]. The physio-pathological roles of these inhibitors are tabulated in Table 1 .

Table 1.

The physio-pathological roles of different inhibitors used against SARS-CoV-2.

| Inhibitors | Physio-pathological role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Protease | Inhibit the cleavages of the long polyprotein chains to provide necessary proteins for replication of the virus | [37] |

| Polymerase | Inhibit viral replication | [38] |

| MTase | Inhibit the prevention of recognition by the host innate immune system | [39] |

| Exonuclease | Inhibit resistance to many of the available antivirals | [40] |

| Receptor | Inhibit the binding of virus to the host cells | [41] |

| Viral fusion | Inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 S protein-mediated cell-cell fusion | [42] |

3. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp)

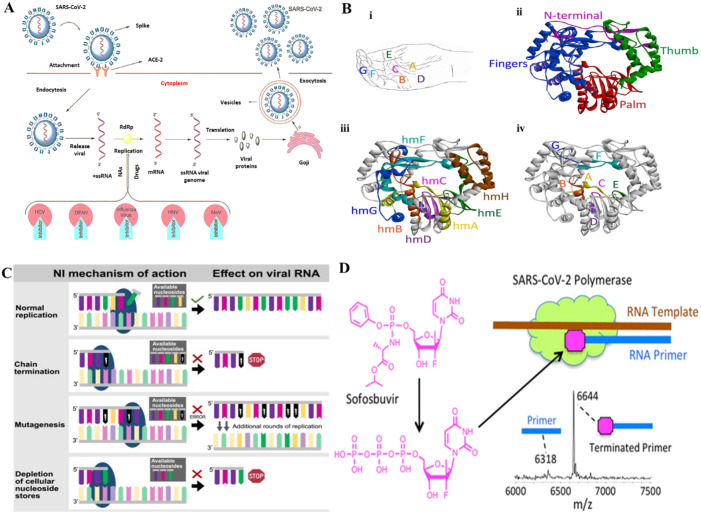

The activity of RdRp is vital for +RNA viral replications. After CoV entry into the host cell, the viral RNA, which consists of 14 open reading frames (ORFs), is released into the cytoplasm for viral replication (Fig. 1 A) [43]. The ORFs 1a and 1b segments assemble two replication polyproteins which are further hydrolyzed in different non-structural proteins (nsps). The RdRp (nsp12) is involved in CoV genomes and protein synthesis [44]. RdRp is known to play a crucial role in the replication of RNA viruses [33]. The deep groove domain as the core segment of RdRp interconnected by fingers [two catalytic domains (F and G)], palm [five catalytic motifs (A–E)], and thumb parts covering the active site of enzyme (Fig. 1B) [45].

Fig. 1.

(A) The life cycle of different RNA viruses via the RdRp (1). (B) Structure of RdRp (PDB ID: 1KHW), (i) motifs, (ii) ribbon structure, (iii) conserved homomorphs, (iv) functional motifs (3). (C) Different inhibition mechanisms by NA (4). (D) Prodrug activation Sofosbuvir and the inhibition of RdRp.

4. Nucleoside analogue (NA) inhibitors

In this review we aimed to present an overview on the application of NAs as potential enzyme inhibitors used to be repurposed as promising candidates in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 polymerase.

In general NAs induce potential preventive effects on viral replication by three well-studied mechanisms (Fig. 1C) [46]. As for different CoVs, amino acid sequence similarity for viral RdRp ranges from 70 to 100%, it is suggested that NAs could promisingly act as wide-ranging inhibitors of CoV infection [47]. However, nsp14-ExoN proofreading activity of CoVs results in their protection from several NAs [48,49]. To potentially inhibit CoVs, well-developed NAs should be designed to either less recognized by ExoN or interact with polymerase at a rate exceeding ExoN excision velocity.

Some NAs are prodrugs, requiring intracellular phosphorylation to induce their antiviral effects [50,51]. In some cases, intracellular phosphorylation is performed by several host enzymes that convert the prodrug into monophosphate, diphosphate, and finally the active trisphosphate forms of these drugs [52].

Ju et al. [53] showed the ability of SARS CoV RdRp, which is almost similar to that of SARS-CoV-2, to incorporate 2′-F, Me-UTP, the active compound of Sofosbuvir prodrug, where it acts as potential agent to terminate the viral RNA replication.

Different NAs have been assessed to explore their efficiency in interacting with the active site of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. In vitro studies and in silico analysis have revealed that some of the broad-spectrum antiviral drugs can be potential therapeutic platforms against the CoVs. NAs imitate the natural substrates of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and result in fast or slow chain termination based on their geometry and binding affinity. It has been shown that Cidofovir triphosphates serves as a potential candidate in a delayed terminator for SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, however Abacavir, Ganciclovir, and Stavudine triphosphates inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, and 2′-O-methylated UTP significantly terminates the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp reaction [54]. Further studies have been reported that Sofosbuvir, Alovudine, Tenofovir alafenamide, AZT, Abacavir, Lamivudine, and Emtricitabine can serve as potential inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp [55] determined by mass spectrometry (MS) Fig. 1D. Also, it has been revealed that rapid interaction of Favipiravir by viral RdRp leads to SARS-CoV-2 lethal mutagenesis [56]. Didanosine is one of the NAs whose administered dose in adults is based on body weight [57]. Repurposing Didanosine as a promising treatment for COVID-19 has been reported based on single-cell RNA sequencing outcomes [57].

5. Prediction of potential commercially NAs against SARS-CoV-2

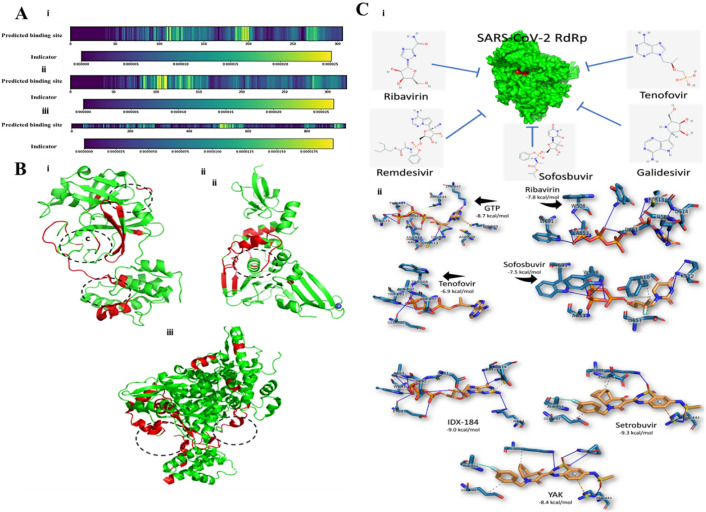

Hu et al. [58] reported that in the computational studies, Abacavir (sulfate) as a NA showed the high binding affinity with several crucial proteins of SARS-CoV-2 such as RdRp, 3C-like protease, papain-like protease, and helicase with different affinities of 3.03 nM, 28.42 nM, 22.90 nM, and 3.06 nM respectively. As depicted in Fig. 2 A, the key domains for binding in protein sequences are screened by heat-map analysis. In the case of 3C-like protease [Fig. 2A(i)], the crucial residues for binding exist at three main parts. It was determined that different kinds of small molecules lead to varying weights of these three segments. For papain-like protease [Fig. 2A(ii)], the preferred binding domains present at the 100-120th residue part. RdRp [Fig. 2A(iii)], shows a key position at 500-584th residues to be a critical binding domain for different small molecules. The ribbon model was also presented to visualize binding domains in 3D structures (Fig. 2B). As displayed in Fig. 2B(i), for 3C-like protease the domain in the middle section (180-200th residues) is the main binding domain because of high weight in most molecular modelling studies. The papain-like protease of SARS-CoV-2 is highly similar to that of SARS. It was shown that the central part of papain-like protease is involved in the interaction with small molecules [Fig. 2B(ii)]. Also, the model predicted for RdRp, showed that two probable sites exist in the protein structure [Fig. 2B(iii)] [58].

Fig. 2.

(A) The binding domain of different protein sequences of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by heat-map analysis. (B) The visualization of 3D structure based on a ribbon model. (i) 3C-like protease, (ii) Papain-like protease, (iii) RdRp [58]. (C) Docking study of different nucleoside analogue and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. (i) Schematic representation, (ii) binding energy calculation and contribution of residues [67].

Ribavirin was reported to show potential antiviral activity against SARS-CoV [59] and MERS-CoV [60]. It was also shown that Acyclovir fleximer as an antiviral agent can inhibit MERS-CoV and HCoV-NL63 infection with IC50 values of 23 μM and 8.3 μM, respectively [61]. Moreover, Remdesivir has been shown to significantly block the replication of human CoV through inhibition of viral polymerase. For example, it was shown that Remdesivir has potential antiviral effects against SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 [47,62,63]. Some other nucleoside analogues such as β-d-N4-hydroxycytidine [64,65] and Gemcitabine [66] show potential antiviral effects against human CoV. Elfiky [67] showed that as SARS-CoV-2 RdRp show 97% homology to SARS, the interaction of different antiviral agents such as Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir with RdRp was docked to explore their binding affinity with SARS-CoV-2 proteins [Fig. 2C(i)]. They found that Setrobuvir, YAK, and IDX-184 show the highest binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 RdRp among other antiviral agents [Fig. 2C(ii)].

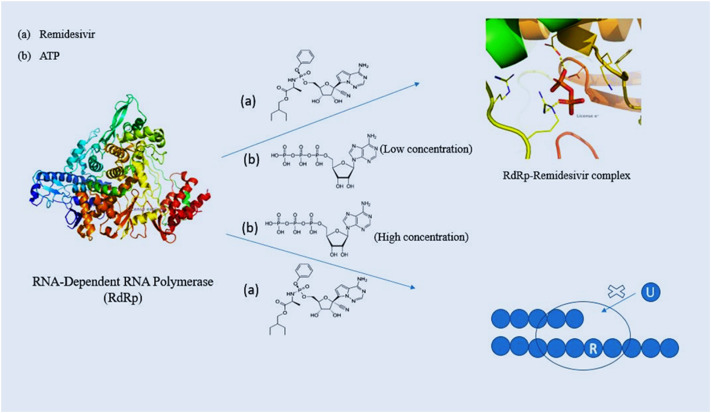

Development of advanced docking algorithms has helped in the molecular recognition of various nucleoside analogue drugs against key inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2, however the stability of the complex formed, viability of molecular interactions and mechanism has been further established by studying their dynamics. In their computational study performed by Zhang and Zhou [68] they have depicted the antiviral property of Remdesivir using molecular dynamics simulations [68]. It has been speculated that Remdesivir acts as a competitive inhibitor of RdRp against its natural inhibitor which is ATP. Free energy perturbation studies have shown that Remdesivir binds to RdRp with a 100-fold K d when compared with ATP. The key residues involved for strong interactions were D618, S549 and R555. The resulting root mean square deviations (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values proved remarkable stability of the protein-drug complex during the course of time [[69], [70], [71], [72]].

The study has been further confirmed under in-vivo conditions performed by Gordon et al. They elaborated the mechanism of Remdesivir antiviral activity and concluded that insertion of the triphosphate form of Remdesivir at a position (i) would terminate the synthesis of RNA at i + 3 position [72]. A second mechanism of inhibition has also been proposed by Tchesnokov et al. [38]. Increased concentrations of NTPs can adversely lower down the RdRp inhibition by Remdesivir. As a result, Remdesivir gets incorporated in the first transcription. It has been observed that upcoming UTP could not get incorporated opposite to Remdesivir residue. This is because of a significant steric clash with A558. This leads to a template dependent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp [38].

Fig. 3 shows the two mechanisms of inhibition by Remdesivir. Although, other nucleoside analogues such as Gemcitabine and Sofosbuvir have shown quite strong interactions when molecular docking has been performed, molecular dynamics studies have revealed a higher RMSD and RMSF values when compared with Remdesivir. In their study, Zhang et al. [73] has shown that the Gemcitabine-RdRp and Sofosbuvir-RdRp complexes when simulated for a timescale of 100 ns have a greater RMSD and RMSF values when compared with Remdesivir [73]. Since molecular dynamics studies require a lot of computational cost therefore not much studies have been performed.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of two different modes of action of Remdesivir. At low concentration of ATP, the RdRp-Remdesivir complex is formed which competitively inhibits the binding of ATP to RdRp. At high concentration, Remdesivir is incorporated in the first transcribe and compromises the uptake of UTP in the second transcribe resulting in chain termination.

6. Clinical development of NAs

The recent advancement of NAs with antiviral efficiency can result in the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapies [74]. The intracellular activation by active phosphorylation and associated metabolism should be considered during development of NAs as antiviral drugs. Several NAs as potential inhibitors of RdRp, such as Favipiravir, Sofosbuvir, Ribavirin, Tenofovir, and Remdesivir, were shown to be potential candidates for the possible treatment of SARS-CoV-2. Table 2 shows the practical considerations of antiviral therapies done against SARS-CoV-2.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes of antiviral therapies reported against SARS-CoV-2.

| Drug | Dosing | Outcome | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|

| Favipiravir | 1600 mg twice daily on day 1, 600 mg twice daily from day 2 to day 5 | Patients had improvement and did not need mechanical ventilation over time, numerical decrease in time to defervescence | [75,76] |

| Sofosbuvir | A single daily oral tablet containing 400 mg for 14 days | Alone or in combination with other antivirals can decrease the median duration of hospital stay | [[77], [78], [79]] |

| Ribavirin | 400 mg every 12 h for ribavirin | In combination with other antivirals shorter median time, improved recovery of 67% | [80,81] |

| Tenofovir | 45 mg daily for 2 years for chronic hepatitis B | Possible clinical protective effect of Tenofovir | [82] |

| Remdesivir | IV over 30 min | Improvement of patients' survival, reduced rate of symptoms, proportion of ICU treatments | [[83], [84], [85], [86]] |

7. Conclusion and remarks

In this paper, some potential NAs were introduced to be repurposed as promising therapeutic candidates for the treatment of COVID-19 based on their interaction with RdRp. Currently, a number of NAs have been studied to inhibit human CoV in vitro and proceed into clinical trials against SARS-CoV-2. However more well-developed NAs are still demanded, considering factors such as therapeutic impacts, adverse effects, feasible synthesis, less labor, and cost effectiveness. It can be suggested that these candidates can be considered for the clinical treatment of COVID-19. Also, researchers should conduct more experiments on these drug candidates to provide guidelines for clinical trials and treatment of the SARS-CoV-2. Since, the rate of global infections is continuously increasing and the COVID-19 outbreak grows into a global concern, this review may pave the way for development of some promising therapeutic platforms.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Key R&D and promotion projects (Science and Technology Project) from Henan Science and Technology Department, NO: 212102310127 and Henan Middle-aged Youth Health Technology Innovation Talent Project, NO: YXKC2020059.

References

- 1.Pal M., Berhanu G., Desalegn C., Kandi V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): an update. Cureus. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J., Zeng H., Gu J., Li H., Zheng L., Zou Q. Progress and prospects on vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines. 2020;8(2):153. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020;1:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. 102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peeri N.C., Shrestha N., Rahman M.S., Zaki R., Tan Z., Bibi S., Baghbanzadeh M., Aghamohammadi N., Zhang W., Haque U. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020;49(3):717–726. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M. Sharifi, A. Hasan, A. Taghizadeh, S. Haghighat, F. Attar, S.H. Bloukh, Z. Edis, M. Xue, S. Khan, M. Falahati, Rapid diagnostics of coronavirus disease 2019 in early stages using nanobiosensors: challenges and opportunities, Talanta (2020) 121704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Giwa A., Desai A. Novel coronavirus COVID-19: an overview for emergency clinicians, Emergency Medicine Practice. COVID-19 FEBRUARY. 2020;22(Suppl 2):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y.-H., Dong J.-H., An W.-M., Lv X.-Y., Yin X.-P., Zhang J.-Z., Dong L., Ma X., Zhang H.-J., Gao B.-L. Clinical and computed tomographic imaging features of novel coronavirus pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 2020;80(4):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adhikari S.P., Meng S., Wu Y.-J., Mao Y.-P., Ye R.-X., Wang Q.-Z., Sun C., Sylvia S., Rozelle S., Raat H. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2020;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji W., Bishnu G., Cai Z., Shen X. Analysis clinical features of COVID-19 infection in secondary epidemic area and report potential biomarkers in evaluation. medRxiv. 2020;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLaren G., Fisher D., Brodie D. Preparing for the most critically ill patients with COVID-19: the potential role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Jama. 2020;323(13):1245–1246. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamblyn S., Salvadori M., St-Louis P., Yeung T., Haroon B., Fox-Robichaud A., Evans G., Forgie S., Hota S., Mubareka S. 2020. Clinical Management of Patients With Moderate to Severe COVID-19-Interim Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prompetchara E., Ketloy C., Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020;38(1):1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W., Zhao Y., Zhang F., Wang Q., Li T., Liu Z., Wang J., Qin Y., Zhang X., Yan X. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the experience of clinical immunologists from China. Clin. Immunol. 2020;214 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stebbing J., Phelan A., Griffin I., Tucker C., Oechsle O., Smith D., Richardson P. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(1):400–402. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong L., Hu S., Gao J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 2020;14(1):58–60. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Y.-R., Cao Q.-D., Hong Z.-S., Tan Y.-Y., Chen S.-D., Jin H.-J., Tan K.-S., Wang D.-Y., Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak–an update on the status. Military Medical Research. 2020;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Duan Y. Structure-based drug design, virtual screening and high-throughput screening rapidly identify antiviral leads targeting COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2020;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar Y., Singh H. 2020. In Silico Identification and Docking-based Drug Repurposing against the Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2, Causative Agent of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shafiee S., Davaran S. A mini-review on the current COVID-19 treatments. Chemical Review and Letters. 2020;3(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamshidi M., Lalbakhsh A., Talla J., Peroutka Z., Hadjilooei F., Lalbakhsh P., Jamshidi M., La Spada L., Mirmozafari M., Dehghani M. Artificial intelligence and COVID-19: deep learning approaches for diagnosis and treatment. IEEE Access. 2020;8:109581–109595. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3001973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcolino V.A., Pimentel T.C., Barão C.E. What to expect from different drugs used in the treatment of COVID-19: a study on applications and in vivo and in vitro results. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;887 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai P., Ding Y., Wu X., Long J., Zhong Y., Li Y. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scavone C., Brusco S., Bertini M., Sportiello L., Rafaniello C., Zoccoli A., Berrino L., Racagni G., Rossi F., Capuano A. Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: what’s next? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177(21):4813–4824. doi: 10.1111/bph.15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K., Li C., Ai Q., Lu W., Liang H. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X.-W., Wu X.-X., Jiang X.-G., Xu K.-J., Ying L.-J., Ma C.-L., Li S.-B., Wang H.-Y., Zhang S., Gao H.-N. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. Bmj. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.K. Dick, K.K. Biggar, J.R. Green, Computational prediction of the comprehensive SARS-CoV-2 vs. human interactome to guide the design of therapeutics, BioRxiv (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Smith M., Smith J.C. 2020. Repurposing Therapeutics for Covid-19: Supercomputer-based Docking to the SARS-CoV-2 Viral Spike Protein and Viral Spike Protein-Human ace2 Interface. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devaux C.A., Rolain J.-M., Colson P., Raoult D. New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55(5):105938–105943. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabirotchkin S., Peluffo A.E., Bouaziz J., Cohen D. 2020. Focusing on the Unfolded Protein Response and Autophagy Related Pathways to Reposition Common Approved Drugs Against COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L., Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systemic review. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J., Cha Y., Kolitz S., Funt J., Chong R. Escalante, Barrett S., Zeskind B., Kusko R., Kaufman H. 2020. Advanced Bioinformatics Rapidly Identifies Existing Therapeutics for Patients With Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X., Wang L., Yan S., Yang F., Xiang L., Zhu J., Shen B., Gong Z. Clinical characteristics of 25 death cases infected with COVID-19 pneumonia: a retrospective review of medical records in a single medical center, Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020;1:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo W., Yu H., Gou J., Li X., Sun Y., Li J., Liu L. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) Pathology & Pathobiology. 2020:2020020407. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes A., Barber T., Nelson M. New treatment options for HIV salvage patients: an overview of second generation PIs, NNRTIs, integrase inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists. J. Infect. 2008;57(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arts E.J., Hazuda D.J. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(4) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babadaei M.M. Nejadi, Hasan A., Vahdani Y., Bloukh S. Haj, Sharifi M., Kachooei E., Haghighat S., Falahati M. Development of remdesivir repositioning as a nucleotide analog against COVID-19 RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics (just-accepted) 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1767210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choudhury C. Fragment tailoring strategy to design novel chemical entities as potential binders of novel corona virus main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1771424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tchesnokov E.P., Gordon C.J., Woolner E., Kocinkova D., Perry J.K., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Götte M. Template-dependent inhibition of coronavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase by remdesivir reveals a second mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(47):16156–16165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.015720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Y., Liu L., Manning M., Bonahoom M., Lotvola A., Yang Z., Yang Z.-Q. Structural analysis, virtual screening and molecular simulation to identify potential inhibitors targeting 2’-O-ribose methyltransferase of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1828172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shannon A., Le N.T.-T., Selisko B., Eydoux C., Alvarez K., Guillemot J.-C., Decroly E., Peersen O., Ferron F., Canard B. Remdesivir and SARS-CoV-2: structural requirements at both nsp12 RdRp and nsp14 exonuclease active-sites. Antivir. Res. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tai W., He L., Zhang X., Pu J., Voronin D., Jiang S., Zhou Y., Du L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2020;17(6):613–620. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y., Yu D., Yan H., Chong H., He Y. Design of potent membrane fusion inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2, an emerging coronavirus with high fusogenic activity. J. Virol. 2020;94(14) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar R., Mishra S., Maurya S.K. Recent advances in the discovery of potent RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors targeting viruses. RSC Medicinal Chemistry. 2021;1:1–5. doi: 10.1039/d0md00318b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y., Anirudhan V., Du R., Cui Q., Rong L. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of SARS-CoV-2 as a therapeutic target. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(1):300–310. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smertina E., Urakova N., Strive T., Frese M. Calicivirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerases: evolution, structure, protein dynamics, and function. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pruijssers A.J., Denison M.R. Nucleoside analogues for the treatment of coronavirus infections. Current Opinion in Virology. 2019;35:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Menachery V.D., Gralinski L.E., Case J.B., Leist S.R., Pyrc K., Feng J.Y., Trantcheva I. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9(396) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith E.C., Blanc H., Vignuzzi M., Denison M.R. Coronaviruses lacking exoribonuclease activity are susceptible to lethal mutagenesis: evidence for proofreading and potential therapeutics. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saijo M., Morikawa S., Fukushi S., Mizutani T., Hasegawa H., Nagata N., Iwata N., Kurane I. Inhibitory effect of mizoribine and ribavirin on the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005;66(2–3):159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein D.S., Moore K.H. Phosphorylation of nucleoside analog antiretrovirals: a review for clinicians. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2001;21(1):11–34. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.1.11.34439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jadav T., Jain S., Kalia K., Sengupta P. Current standing and technical guidance on intracellular drug quantification: a new site specific bioavailability prediction approach. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2020;50(1):50–61. doi: 10.1080/10408347.2019.1570462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho A. vol. I. 2019. Evolution of HCV NS5B Nucleoside and Nucleotide Inhibitors, HCV: The Journey From Discovery to a Cure; pp. 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ju J., Li X, Kumar S., Jockusch S., Chien M., Tao C., Morozova I., Kalachikov S., Kirchdoerfer R., Russo J.J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV polymerase. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020;8(6):e00674. doi: 10.1002/prp2.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jockusch S., Tao C., Li X., Anderson T.K., Chien M., Kumar S., Russo J.J., Kirchdoerfer R.N., Ju J. A library of nucleotide analogues terminate RNA synthesis catalyzed by polymerases of coronaviruses that cause SARS and COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020;180 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chien M., Anderson T.K., Jockusch S., Tao C., Li X., Kumar S., Russo J.J., Kirchdoerfer R.N., Ju J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase, a key drug target for COVID-19. J. Proteome Res. 2020;19(11):4690–4697. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon A., Selisko B., Huchting J., Touret F., Piorkowski G., Fattorini V., Ferron F., Decroly E., Meier C., Coutard B. Rapid incorporation of Favipiravir by the fast and permissive viral RNA polymerase complex results in SARS-CoV-2 lethal mutagenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18463-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alakwaa F.M. Repurposing didanosine as a potential treatment for COVID-19 using single-cell RNA sequencing data. Msystems. 2020;5(2) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00297-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.F. Hu, J. Jiang, P. Yin, Prediction of potential commercially inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 by multi-task deep model, arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.00728 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Chen F., Chan K., Jiang Y., Kao R., Lu H., Fan K., Cheng V., Tsui W., Hung I., Lee T. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan J.F., Chan K.-H., Kao R.Y., To K.K., Zheng B.-J., Li C.P., Li P.T., Dai J., Mok F.K., Chen H. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. 2013;67(6):606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peters H.L., Jochmans D., de Wilde A.H., Posthuma C.C., Snijder E.J., Neyts J., Seley-Radtke K.L. Design, synthesis and evaluation of a series of acyclic fleximer nucleoside analogues with anti-coronavirus activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25(15):2923–2926. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X., Smith E.C., Case J.B., Feng J.Y., Jordan R. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. MBio. 2018;9(2) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R., Schäfer A., Won J., Brown A.J., Montgomery S.A., Hogg A., Babusis D., Clarke M.O. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnard D.L., Day C.W., Bailey K., Heiner M., Montgomery R., Lauridsen L., Chan P.K., Sidwell R.W. Evaluation of immunomodulators, interferons and known in vitro SARS-coV inhibitors for inhibition of SARS-coV replication in BALB/c mice. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2006;17(5):275–284. doi: 10.1177/095632020601700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pyrc K., Bosch B.J., Berkhout B., Jebbink M.F., Dijkman R., Rottier P., van der Hoek L. Inhibition of human coronavirus NL63 infection at early stages of the replication cycle. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50(6):2000–2008. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01598-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dyall J., Coleman C.M., Hart B.J., Venkataraman T., Holbrook M.R., Kindrachuk J., Johnson R.F., Olinger G.G., Jahrling P.B., Laidlaw M. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58(8):4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03036-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elfiky A.A. Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020;253:117592–117597. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang L., Zhou R. Structural basis of potential binding mechanism of remdesivir to SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124(32):6955–6962. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c04198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.M. Arba, S.T. Wahyudi, D.J. Brunt, N. Paradis, C. Wu, Mechanistic insight on the remdesivir binding to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of SARS-cov-2, Comput. Biol. Med. (2020) 104156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Koulgi S., Jani V., Uppuladinne M.V., Sonavane U., Joshi R. Remdesivir-bound and ligand-free simulations reveal the probable mechanism of inhibiting the RNA dependent RNA polymerase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. RSC Adv. 2020;10(45):26792–26803. doi: 10.1039/d0ra04743k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wakchaure P.D., Ghosh S., Ganguly B. Revealing the inhibition mechanism of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of SARS-CoV-2 by Remdesivir and nucleotide analogues: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124(47):10641–10652. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Woolner E., Perry J.K., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Götte M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(20):6785–6797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang H., Yang Y., Li J., Wang M., Saravanan K.M., Wei J., Ng J.T.-Y., Hossain M.T., Liu M., Zhang H. 2020. FDA-approved Pralatrexate Identified by Virtual Drug Screening Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication In Vitro. [Google Scholar]

- 74.M. Chien, T.K. Anderson, S. Jockusch, C. Tao, S. Kumar, X. Li, J.J. Russo, R. Kirchdoerfer, J. Ju, Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase, bioRxiv (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Irie K., Nakagawa A., Fujita H., Tamura R., Eto M., Ikesue H., Muroi N., Tomii K., Hashida T. Pharmacokinetics of Favipiravir in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Clinical and Translational Science. 2020;13(5):880–885. doi: 10.1111/cts.12827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dauby N., Van Praet S., Vanhomwegen C., Veliziotis I., Konopnicki D., Roman A. Tolerability of favipiravir therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a report of four cases. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(2):689–691. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sadeghi A., Ali Asgari A., Norouzi A., Kheiri Z., Anushirvani A., Montazeri M., Hosamirudsai H., Afhami S., Akbarpour E., Aliannejad R. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir compared with standard of care in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with moderate or severe coronavirus infection (COVID-19): a randomized controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75(11):3379–3385. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abbaspour Kasgari H., Moradi S., Shabani A.M., Babamahmoodi F., Davoudi Badabi A.R., Davoudi L., Alikhani A., Hedayatizadeh Omran A., Saeedi M., Merat S. Evaluation of the efficacy of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir in combination with ribavirin for hospitalized COVID-19 patients with moderate disease compared with standard care: a single-centre, randomized controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75(11):3373–3378. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roozbeh F., Saeedi M., Alizadeh-Navaei R., Hedayatizadeh-Omran A., Merat S., Wentzel H., Levi J., Hill A., Shamshirian A. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for the treatment of COVID-19 outpatients: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;76(3):753–757. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hung I.F.-N., Lung K.-C., Tso E.Y.-K., Liu R., Chung T.W.-H., Chu M.-Y., Ng Y.-Y., Lo J., Chan J., Tam A.R. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eslami G., Mousaviasl S., Radmanesh E., Jelvay S., Bitaraf S., Simmons B., Wentzel H., Hill A., Sadeghi A., Freeman J. The impact of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir or ribavirin in patients with severe COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75(11):3366–3372. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kutlu O. Can Tenofovir diphosphate be a candidate drug for Sars-Cov2? First clinical perspective. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021:e13792. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Potì F., Pozzoli C., Adami M., Poli E., Costa L.G. Treatments for COVID-19: emerging drugs against the coronavirus. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(2):118. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barlow A., Landolf K.M., Barlow B., Yeung S.Y.A., Heavner J.J., Claassen C.W., Heavner M.S. Review of emerging pharmacotherapy for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2020;40(5):416–437. doi: 10.1002/phar.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spinner C.D., Gottlieb R.L., Criner G.J., López J.R.A., Cattelan A.M., Viladomiu A.S., Ogbuagu O., Malhotra P., Mullane K.M., Castagna A. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2020;324(11):1048–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]