Abstract

Hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis) was linked to dementia long ago, but subsequently, Alzheimer’s plaques and tangles have received more attention. A new proteome-wide association study unveils molecular links between intracranial atherosclerosis and dementia, independent of other pathologies, providing new evidence for one of the oldest suspected causes of dementia.

The world’s aging population is facing the prospect of a dementia epidemic, which is anticipated to bankrupt health care systems worldwide. This has spurred national plans to contain its devastating impact1. A better understanding of disease pathobiology is necessary to combat dementia, and most efforts to date have focused on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its pathological hallmarks, amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles2. In the early 1900s, atherosclerotic hardening of the arteries was widely recognized as the leading cause of cognitive impairment, but with recognition of AD as a distinct nosological entity, less attention was devoted to vascular causes of dementia. Subsequently, a wealth of prospective epidemiological data demonstrated that vascular risk factors present in midlife, including (but not limited to) hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia are associated with a clinical diagnosis of AD later in life3. At the same time, clinical pathological data from community-based cohorts revealed that most individuals diagnosed with AD have a combination of vascular alterations, plaques and tangles, and other pathologies as well (see below). Coexistence of AD and vascular pathology was found to lower the threshold for cognitive impairment, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two4. Imaging studies showed that cerebrovascular function is compromised in patients at genetic risk for AD and that cerebrovascular alterations may be the earliest biomarker of sporadic AD5. Based on this evidence, it has become well-accepted that dementia in the elderly, defined as AD on clinical grounds, includes overlapping pathogenic processes including cerebrovascular factors2. But, the relative contribution of these pathologies to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD (MCI–AD) and their role in initiating the molecular changes driving cognitive impairment remains unclear. Addressing these questions has great relevance to disease mechanisms, prevention, diagnosis and therapy.

In this issue of Nature Neuroscience, Wingo and colleagues6 report on a brain proteomic study in community-based cohorts with MCI and full-blown AD. Atherosclerosis (accumulation of fat and calcium leading to hardening of the vessel wall and luminal narrowing; ATS) in large intracranial arteries was associated with MCI–AD independently of eight other brain pathologies. ATS was independently linked to protein expression changes indicative of reduced synaptic function, excess myelination and accumulation of the neuronal scaffolding proteins neurofilament light (NEFL) and medium chain (NEFM), suggesting a role in axonal injury. Remarkably, the proteomic changes induced by ATS could not be attributed to coexisting small or large ischemic lesions, unveiling a direct molecular link between intracranial ATS and MCI–AD.

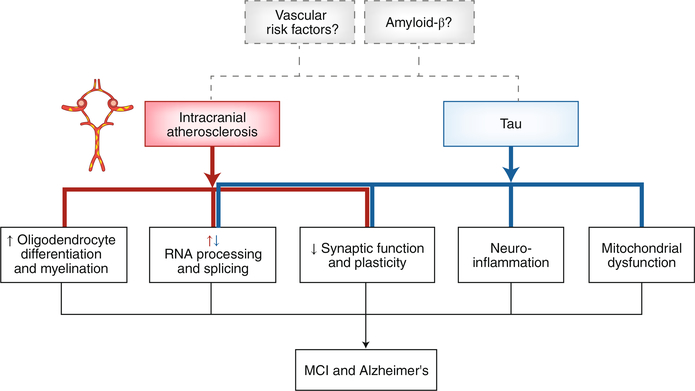

Wingo et al.6 performed a large-scale proteome-wide association study (PWAS) in 438 postmortem brains from discovery and validation cohorts. The discovery cohorts (Religious Order Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project) consisted of individuals with normal cognition at enrollment (age 80), who were followed annually with clinical and cognitive evaluations and underwent brain autopsy after death (average age 89). At death, the cohort included individuals with normal cognition (41%), AD dementia (31%), MCI (26%) and other dementias (2%). The nine pathologies assessed postmortem were Aβ, neurofibrillary tangles, ATS of the circle of Willis and proximal arteries, gross infarcts, microinfarcts, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43), Lewy bodies, and hippocampal sclerosis. Of the 8,356 proteins isolated from the prefrontal cortex, approximately 10% were differentially expressed in brains from those with MCI–AD compared to cognitively normal controls. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis followed by gene set enrichment revealed that MCI–AD was associated with changes in protein modules reflecting decreased synaptic function and plasticity, decreased energy production and protein synthesis in mitochondria, increased inflammation and myelination, and increased neuronal RNA splicing. Tangles were independently associated with some of these protein changes, most notably synaptic dysfunction, inflammation and neuronal RNA splicing, but Aβ had no independent association with any of the protein co-expression modules (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 |. ATS of the circle of Willis and proximal arterial branches is linked to MCI–AD through proteomic changes in the prefrontal cortex independent of tau, TDP43, Aβ, Lewy bodies, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, macro- and microinfarcts, and hippocampal sclerosis.

Tau is also independently linked to AD–MCI, through proteomic changes in part overlapping with ATS. In RNA processing and splicing, ATS and tau have opposite effects. Aβ is not directly linked to proteomic changes associated with MCI–AD, but since these data are from an autopsy study the possibility that vascular risk factors and Aβ are involved early in the disease process, for which there is biological plausibility, cannot be ruled out.

Next, the authors examined the specific contribution of ATS to the proteomic changes in MCI–AD. PWAS identified 114 differentially expressed proteins, 82 with lower abundance and 32 with higher abundance. Protein co-expression analysis revealed an association of ATS with modules linked to (i) enhanced oligodendrocyte differentiation, development and remyelination; (ii) reduced neuronal and astrocytic RNA splicing and processing; and (iii) decreased synaptic signaling, regulation and plasticity. Not only were these proteomic changes independent of plaques, tangles, TDP-43, hippocampal sclerosis and Lewy bodies, but also of vascular pathologies potentially caused by ATS (gross infarcts and microinfarcts), CAA and vascular risk factors, as verified in three independent sensitivity analyses and validated in a replication cohort. Furthermore, to confirm the changes in oligodendrocytes, the authors used a published single-nucleus RNA-sequencing dataset from a sample that overlapped with the discovery cohort and, in agreement with the proteomic changes, found an increase in oligodendrocytes, independent of the other pathologies. These findings link circle of Willis ATS to major proteomic alterations in neurons, astrocytes and oligodendroglia, not related to coexisting neurodegenerative or ischemic pathology.

To gain insight into the potential molecular mechanisms by which ATS exerts its harmful effects on cognitive health, the authors took a closer look at the proteins uniquely associated with ATS and MCI–AD. Co-expression modules with increased abundance were related to myelination and oligodendrocytes, whereas modules with decreased abundance were linked to synaptic signaling and plasticity. Of the increased proteins, NEFL and NEFM were of particular interest since they are markers of axonal injury and their level in the cerebrospinal fluid tracks with AD progression7. Additional analyses revealed that NEFL and NEFM, the levels of which correlated with the severity of cognitive dysfunction, were associated only with ATS and not with the other eight pathologies. These findings, collectively, suggest that intracranial ATS is an independent driver of cognitive impairment in MCI–AD through proteomic changes reflecting axonal injury and synaptic dysfunction (Fig. 1).

The idea that hardening of the arteries may play a role in AD has recently re-emerged, but the evidence has been contradictory, largely due to differences in the vascular segments studied (intra-or extracranial), how AD pathology was assessed (clinical imaging or autopsy), presence or absence of cognitive impairment, among other measures (see for example refs. 8–10). The present findings, from community-based cohorts with MCI–AD in which brain and intracranial vessels were assessed pathologically, the gold standard, lend strong support to the view that ATS is directly linked to MCI–AD.

But how does ATS lead to cognitive impairment independently of ischemic brain lesions or neurodegenerative pathology? Perhaps ATS is the end result of longstanding neurovascular dysfunction, which could contribute to brain dysfunction and axonal damage by a subtle reduction in microvascular perfusion without causing overt ischemic lesions. Blood-flow-independent aspects of neurovascular function, such as blood–brain barrier permeability, neurotrophic support by endothelial cells or neuroimmune modulation, could also be involved11. Recent evidence linking cerebral endothelial dysfunction to cognitive impairment without compromising cerebral blood flow supports this hypothesis12,13.

It is also unclear why tau pathology, also independently associated with MCI–AD and proteomic changes suggesting brain damage, was not linked to increases in NEFL and NEFM, markers of axonal injury. Another surprise is that Aβ, a major pathogenic factor in AD, was not independently associated with proteomic changes or other pathologies, except by a weak negative association with ATS. Perhaps Aβ could play a prominent role early in the disease process by inducing neurovascular dysfunction and promoting the other pathologies, but its molecular impact is no longer appreciated when the pathology is fully developed, as in the present autopsy study. This is a shortcoming of autopsy studies in which the factors initiating the disease process and contributing to its temporal evolution cannot be assessed. In vivo investigations of the evolution of the impact of the different pathologies on brain damage and cognition would be desirable, but reliable biomarkers for the diverse pathologies observed in MCI–AD brains would be needed.

Finally, would preventing ATS reduce dementia risk? Control of vascular risk factors is well documented to reduce ATS, which, in turn, could prevent cognitive impairment, at least in part. Hints that this may be the case come from multimodal lifestyle interventions trials and hypertension trials suggesting that control of vascular risk factors has beneficial effects on cognition14,15. Regardless of these outstanding questions, Wingo et al. provide an illuminating look at the molecular impact that intracranial ATS exerts on the brain and on cognitive function. While the associations reported in the paper do not demonstrate causation, the molecular clues provided by the proteomic network analysis, if validated, set the stage for further investigations that may lead to new biomarkers and therapeutic targets. In the meantime, preserving cerebrovascular health by controlling vascular risk factors, eating a healthy diet and engaging in physical and mental exercise might be the most sensible approaches to forestall cognitive impairment.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia. WHO; http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. (Accessed 18 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hachinski V et al. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 961–984 (2019).31327392 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iadecola C & Gottesman RF Circ. Res 123, 406–408 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iadecola C et al. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 73, 3326–3344 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Pérez JM & Evans AC Nat. Commun 7, 11934 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingo AP Nat. Neurosci 10.1038/s41593-020-0635-5 (2020). [DOI]

- 7.Preische O et al. Nat. Med 25, 277–283 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roher AE et al. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 23, 2055–2062 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottesman RF et al. JAMA Neurol. 77, 350–357 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustavsson A-M et al. Ann. Neurol 87, 52–62 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iadecola C Neuron 96, 17–42 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan C et al. Neuron 101, 920–937.e13 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraco G et al. Nature 574, 686–690 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iadecola C & Gottesman RF Circ. Res 124, 1025–1044 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F & Ngandu T Nat. Rev. Neurol 14, 653–666 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]