Abstract

While artificial pancreas (AP) systems are expected to improve the quality of life among people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the design of convenient systems that optimize the user experience, especially for those with active lifestyles, such as children and adolescents, still remains an open research question. In this work, we introduce an embeddable design and implementation of model predictive control (MPC) of AP systems for people with T1DM that significantly reduces the weight and on-body footprint of the AP system. The embeddable controller is based on a zone MPC that has been evaluated in multiple clinical studies. The proposed embedded zone MPC features a simpler design of the periodic safe zone in the cost function and the utilization of state-of-the-art alternating minimization algorithms for solving the convex programming problems inherent to MPC with linear models subject to convex constraints. Off-line closed-loop data generated by the FDA-accepted UVA/Padova simulator is used to select an optimization algorithm and corresponding tuning parameters. Through hardware-in-the-loop in silico results on a limited-resource Arduino Zero (Feather M0) platform, we demonstrate the potential of the proposed embedded MPC. In spite of resource limitations, our embedded zone MPC manages to achieve comparable performance of that of the full-version zone MPC implemented in a 64-bit desktop for scenarios with/without meal-disturbance compensations. Metrics for performance comparison included median percent time in the euglycemic ([70, 180] mg/dL range) of 84.3% vs. 83.1% for announced meals, with an equivalence test yielding p = 0.0013 and 66.2% vs. 66.0% for unannounced meals with p = 0.0028.

Keywords: Artificial pancreas, model predictive control, safety-critical control, convex optimization, embedded systems, biomedical control, control applications

I. Introduction

People with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) require exogenous insulin to protect against dangerous blood glucose (BG) excursions occurring due to ingested meals or active lifestyles. The artificial pancreas (AP) is a smart medical device that systematically provides appropriate insulin boluses to prevent prolonged times in hypoglycemia (BG<70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemia (BG>180 mg/dL) [1]. Since the AP system is critical to the quality of care, people with T1DM always need the continuous glucose monitor (CGM), insulin pump, and decision-making module comprising the automatic controller to be part of an on-body ecosystem. In order to improve quality of life and abet active lifestyles, such an on-body ecosystem needs to be wearable: miniaturized and light-weight [2]. The development of a fully wearable AP is an active concern for people with diabetes and diabetes researchers [3], [4], [5], [1] and is the main subject of this paper.

A crucial step towards a wearable AP involves modifying the control algorithm. Many AP control algorithms are developed on personal computer-based platforms and are not suitable for wearable implementation in their current form. The wearable AP system requires next-generation controller algorithms to perform on low-power, low-memory hardware. Recent work has shown effective implementations of wearable closed-loop AP systems in outpatient clinical trials. Successful outpatient, closed-loop control trials were demonstrated in [6], [7], [8], [9] using a control algorithm deployed from a dedicated smartphone working in conjunction with an insulin pump and CGM. Other research has recently focused on integrating the control algorithm for the AP on the same devices as the insulin pump to reduce the number of the system components [10]. Medtronic has recently released the first commercially available hybrid closed-loop artificial pancreas system that utilizes a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller deployed on the same device as the insulin pump [11].

The next generation wearable AP system will be small in size to not only accommodate ease of use and improved quality of life of the end-user but also for eventual implantation in the body, as discussed in [12], [13]. One of the main challenges that arises from miniaturizing the AP system is deploying advanced control algorithms from low-memory, low-complexity hardware without compromising precision and safety (via constraint satisfaction). The challenge is more prominent in optimization-based control approaches like MPC, which has been clinically validated as a promising closed-loop control algorithm for treating T1DM [14], [15]. In particular, MPC is promising for T1DM control due to ability to optimize performance given a set of constraints, such as glucose levels and insulin-on-board, over short predictive horizons using insulin-glucose dynamical models. Additionally, MPC is advantageous because it allows for the inclusion of different objectives (set-point tracking and zone) and the inclusion of the effects of events, such as meals and exercise [14]. A limitation of traditional MPC is that it requires high computational overhead which poses implementation challenges when deployed on low-complexity hardware: this has given rise to a common misconception that MPC cannot be implemented at all on embedded systems. This is less of a problem for other control algorithms like PID [16] and fuzzy logic [17].

In fact, the control engineering community has provided many avenues of implementing MPC on embedded platforms by exploiting the structure of the intrinsic optimization problem. An additional feature that can be exploited is the slow variation of insulin-glucose dynamics. This has led to the development of event-based control [18], [19] and estimation [20] algorithms that reduce the on-time of the control module. Another key direction for reducing MPC complexity is by designing optimization solvers that exploit specific nuances of the finite horizon optimal control problem. Careful selection of solvers for specific optimization problems provides significant advantages in embedded control applications [21], [22]. Recent methods for solving constrained quadratic programs (QPs) include: interior-point method with convergence depth control [23], dual gradient methods [24], contractive set constraints [25], alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) [26], and a least distance problem based on nonnegative least squares [27]. An alternative to online MPC that aims to overcome the complexity of solving online the repetitive optimization problem is the explicit/multi-parametric MPC (mp-MPC), as described in [28], [29], [30], [31]. Embedded nonlinear MPC frameworks have also been proposed [32] by exploiting problem structure, and leveraging data-driven methods in [33].

In this paper, we recast the classical periodic zone MPC formulated in [34] for embedded implementation. Concretely, we use alternating minimization algorithms (also known as splitting methods) to solve for appropriate insulin doses in a memory- and time-efficient manner. These algorithms have proven useful in solving strongly convex programming problems and have recently started gaining traction in linear MPC for embeddable implementation [35]. Alternating minimization algorithms (AMAs) are efficient because they split a complex convex optimization problem into simpler subproblems and solve them in a computationally efficacious manner. A very popular splitting method known as the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) has shown rapid and reliable performance in an MPC setting [26], [36]. However, some recent work [37] extols the effectiveness of an alternative splitting method known as fast alternating minimization algorithm (FAMA) for solving MPC problems with polytopic and second-order cone constraints, and complexity certificates are provided. In this paper, we adopt the method in [37] and use an FAMA-based periodic zone MPC [38], [39], [40] for embedded implementation on a wearable AP. We demonstrate that the FAMA algorithm provides practical benefits over other state-of-the-art splitting algorithms. We also test the proposed embedded AP in a severely resource constrained environment: an Arduino Feather M0. We investigate the reliability and rapidity of embedded control using a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulations by connecting the embedded AP to the UVA/Padova metabolic simulator typically used for pre-clinical trial testing. The wearable AP system with the embedded control module is demonstrably safe and behaves similarly to a 64-bit PC implementation of the algorithm from a clinical perspective.

II. Model Predictive Control for Type 1 Diabetes

In the following, we briefly introduce the main components in MPC of AP through a particular embodiment named zone MPC [38], [39], [40], which is also the starting point of our embedded MPC design.

Specifically, zone MPC identifies the optimal control trajectories by solving a constrained optimization problem at each controller update time instant n:

| (1) |

subject to:

Here, we have an objective function

that penalizes zk, the distance of glucose prediction y from a predefined diurnal zone

| (2) |

The predictive model is a third-order linear control-relevant state-space system [41]

that calculates the future glucose trajectories based on a sequence of control inputs within the prediction horizon Np. The parameterization of A, B and C can be found in [39].

A set of safety constraints g(xk, uk) ≤ 0 that describe the limitations of system operation. Two types of constraints are considered in zone MPC. The first constraint directly imposes constant upper and lower bounds on insulin delivery. The control action uk must also respect an upper bound that takes into account the administered insulin history and computes the remaining active insulin in the body based on clearance rates in the human endocrine system. This is commonly referred to as the insulin-on-board (IOB) upper bound [42]. The active insulin content can then be leveraged to formulate a constraint (the IOB constraint) to restrict the allowable magnitude of insulin infused, thereby preventing an overdose. Empirical clinically validated insulin action curves are used to compute the current IOB value. These discretized curves are sampled every τ min and represent the fraction of insulin that remains active after 2, 4, 6 and 8 hours. Detailed design and parameterization of the constraints can be found in [39].

Note that in our description, we denote the starting point of the prediction at all time instants n as k = 0. At each controller update time instant n, MPC solves problem (1) and obtains the optimal control sequence {}. The first element is executed and the rest of sequence is ignored. This procedure is performed in a receding horizon fashion with the increment of time n. Also note that the state predictions are built on the knowledge of x0, which is usually not known as only the sensor measurements {yn} are available. Thus it is necessary to estimate x0 based on {yn} utilizing a state estimator. In zone MPC, a linear observer is used to achieve this task, which is designed as

where Q = I3, and R = 1000.

In current AP systems, MPC is usually implemented on mobile computing platforms with (reasonably) unrestricted computing and power resources, e.g., laptops, tablets and mobile phones. In the next-generation of AP technology, we envision further miniaturization and eventual implantation within the body. To this end, it is imperative to consider the factors involved in allowing miniaturization of the device. In this regard, customized MPC that can reliably run on a chip with comparable performance of an usual full-strength MPC needs to be designed, which motivates the developments in this work. Specifically, we aim to design an embeddable MPC that simultaneously satisfies memory-size specification of the chip and glucose management performance requirement from a patient.

III. Embedded Periodic Zone MPC for AP

The embedded zone MPC controller is developed based on the classical zone MPC used in AP research [39] with two key modifications: 1) the periodic zone changes do not transition smoothly; that is, the zone boundaries jump abruptly depending on the time of day, 2) the optimization solver is rewritten to ensure efficient and low-footprint implementation on-chip. The detailed design is presented in this section.

A. Zone MPC Formulation for Embedded Implementation

The control objective is to regulate the subject’s glucose level yk to within a time-dependent periodic zone of safe glucose values. As hypothesized in [39], employing a periodic zone as a glucose target rather than a fixed set point offers various clinical advantages such as reduction of nocturnal hypoglycemic events due to conservative infusion of insulin. The smooth upper and lower bounds and in (2) used in [39], however, add to the code size/computation burden of the embedded MPC. If a smooth zone switching was implemented, this would require the storage of matrices pertinent to the optimization problem for multiple convex combinations of the day-time and night-time parameters. Since each convex combination of parameters manifests itself as a different matrix in the optimization problem (and not a convex combination of the matrices themselves), this implementation requires storage of multiple matrices, which in turn, increases the memory budget. To avoid this strain on resources, an abrupt zone change is adopted in this work. To do this, we parameterize the periodic zone using piece-wise constant lower and upper bounds given by , , and ; these are design parameters determined from clinical considerations. In practice, these zones can be adjusted and personalized for different lifestyles. For simplicity, in the embedded implementation these zones are set as daytime and nighttime. The switch between the zones is done abruptly at 11PM and 7AM as shown in Fig. 1 in order to lower computations and save on-chip memory.

Fig. 1:

Periodic zone for embedded zone MPC. The orange shade depicts the glucose zone in the day time (7AM to 11PM) and the blue shade depicts the zone at night (11PM to 7AM).

The rest of the theoretical underpinnings of zone MPC are maintained to avoid deviation of clinically proven performance; instead, hardware-specific optimizations are proposed in the algorithm implementation phase that will be described in subsequent subsections. To summarize, the embedded zone MPC solves the following finite-horizon constrained optimization problem at each controller update instant n:

subject to:

with

Here, k denotes the prediction step and tk denotes the time of day at the i + k step. The time is represented by hours past midnight. We have u, x, and y as the predicted input, the state, and the glucose output. The prediction horizon and control horizon are denoted by Ny and Nu, respectively. is the weighting coefficient for non-negative control inputs and is the weighting coefficient for non-positive control inputs. The basal glucose is denoted by y* and limits of the periodic glucose zone are given by and . Excursions of control actions above and below the basal insulin is given by and , respectively. These insulin excursions are penalized by the matrices and , and the glucose deviation from the zone is penalized by the matrix Q ≻ 0.

B. Solving Periodic Zone MPC on a Chip

The finite-horizon optimal control problem described above can be written as a quadratic program (QP) as discussed in [39], [40], which can be described as

| (3) |

subject to: .

This is particularly advantageous because is positive definite, indicating that the problem (3) is strongly convex. Fast solvers for strongly convex problems like QPs are available in the literature, and can be customized for efficient embedded implementation within the on-body AP ecosystem.

Algorithm 1.

FAMA for QP [43]

| 1: | choose step size , σQ being the strong convexity modulus of Q; |

| 2: | choose total number of iterations to run, N; |

| 3: | initialize vector λ−1, (same dimensions as ) randomly (e.g., as zero); |

| 4: | choose initial dual parameter, α0; |

| 5: | while termination conditions not satisfied do |

| 6: | ; |

| 7: | ; |

| 8: | ; |

| 9: | |

| 10: | ; |

| 11: | end while |

1). Alternating minimization methods:

After comparing with other fast solvers for MPC found in the literature, we focus on alternating minimization methods and consider the fast alternating minimization algorithm (FAMA) and fast alternating direction method of multipliers (FADMM) described in [43], because they offer benefits such as lowered memory requirements for computation, and high-speed of convergence, which implies that the processor does not need to be switched on for long periods of time [19]. We implement these two algorithms and analyze the performance of embedded computation. Description of the algorithms are summarized in Algorithms 1 and 2, which are obtained by applying the algorithms (FAMA/FADMM) to the QP problem in (3).

2). Selection of algorithm parameters:

We employ the FDA-accepted UVA/Padova metabolic simulator to generate data for selecting parameters in the optimization algorithms. The specific parameters we consider tuning are the step-size, τ, and the maximum number of iterations, N. We begin by constructing a regular grid of combinations of τ × N with τ ∈ [0.1, 2] and N ∈ [100, 2000]. Both the FAMA- and FADMM-based embedded ZMPC algorithm are tested on one patient in the metabolic simulator for each grid point and the insulin commands are compared against a 64-bit implementation. Let {U64} denote the sequence of controls computed by solving (3) using MATLAB quadprog in a 64-bit MATLAB implementation and {Uj} denote the corresponding sequence of controls on-chip using the jth grid point (τj, Nj) for each algorithm (FAMA or FADMM). A grid point is marked feasible if the sum-squared error between the two control sequences, namely ε := ‖Uj − U64‖2 is within some tolerance ε0. The set of feasible points are illustrate in Fig. 2, with the chosen tolerance being ε0 = 10−2.

Fig. 2:

Feasible combinations of the maximum number of iterations N and the tuning parameter τ for the [A] FAMA algorithm, [B] FADMM algorithm.

Algorithm 2.

FADMM for QP [43]

| 1: | choose step size τ ∈ (0, 1), σQ being the strong convexity modulus of Q; |

| 2: | choose total number of iterations to run, N; |

| 3: | initialize vector λ−1, (same dimensions as ) randomly (e.g., as zero); |

| 4: | choose initial dual parameter, α0; |

| 5: | while termination conditions not satisfied do |

| 6: | ; |

| 7: | ; |

| 8: | ; |

| 9: | ; |

| 10: | |

| 11: | ; |

| 12: | end while |

We choose N = 800 and τ = 1.6 and the FAMA algorithm. Note that this combination of N and τ is feasible for both FAMA and FADMM, and exhibits a suitable trade-off between computational time (which increases with large N) and solution accuracy (related to τ). There are some clear advantages to FAMA over FADMM, as discussed in [37]. While FADMM requires the primal and dual objectives merely to be convex, FAMA requires strong convexity of one and convexity of the other which is a stronger assumption, but in applications where this is satisfied (such as this one) FAMA exhibits faster convergence rates than FADMM [35]. Another major advantage is that complexity bounds on the number of iterations and step size are calculable for the FAMA algorithm, which is not the case for ADMM in general.

IV. Hardware-in-the-loop Experimental Evaluation

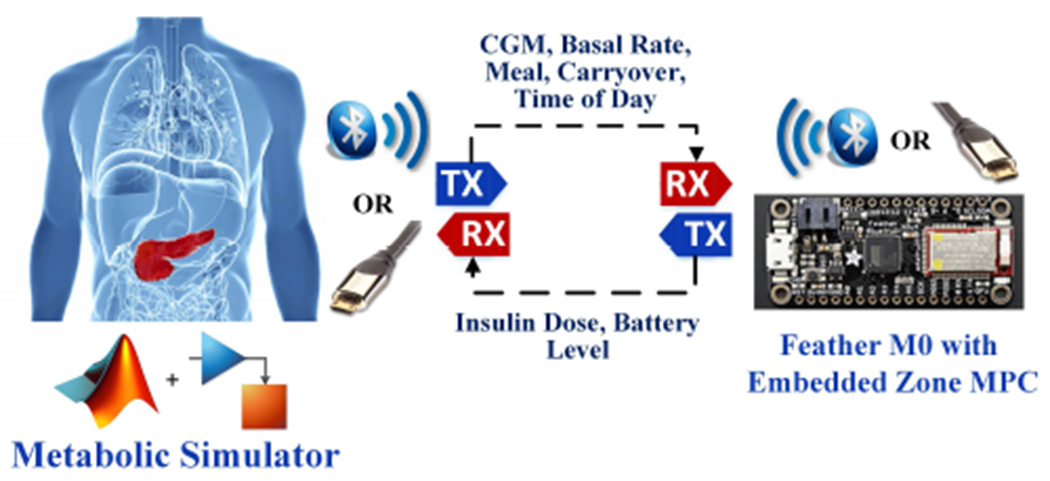

The proposed embedded zone MPC is implemented on Adafruit Feather M0 Bluefruit LE©, an off-the-shelf development board from Adafruit that supports Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) with built in USB and battery charging. The embedded MPC code supports both serial and BLE communication that transmit external input information (e.g., CGM measurements, basal rate, meal information) and output information (e.g., size of insulin dose, battery level) from the Feather M0. The Adafruit Feather M0 is a test tool to demonstrate that a periodic zone MPC can be implemented without significant performance degradation on an embedded platform. While an embedded AP will indeed be customized to the extreme, testing on an M0 serves as a base to allow for potential deployment on higher-end microprocessors and to provide insights into the feasibility of a complex algorithm like MPC on severely resource-constrained environments.

To evaluate the performance of the developed embedded zone MPC, we simulate the human glucose metabolic process using the US FDA-accepted UVA/Padova T1DM simulator [44]. The MPC solver code was written initially in ANSI-C and then adapted to Arduino-C. Specifically, a desktop that runs the UVA/Padova simulator mimics a human wearing a CGM and insulin pump, which sends the input information needed for the embedded zone MPC through serial/BLE communication. The embedded device then runs the MPC algorithm and sends the calculated insulin dose to the desktop through serial/BLE communication. An illustration of the experimental architecture is provided in Fig. 3. To evaluate the glucose regulation performance of the embedded zone MPC, a 41-hour in silico protocol that spread over three days is considered. The protocol starts at 4 PM on Day 1. A 75 g carbohydrate (CHO) dinner is provided at 6 PM, after which a 40 g CHO snack is consumed. Meal challenges of [60, 75, 75] g CHO are provided on Day 2, which take place at 8 AM, 1 PM and 9 PM, and represent breakfast, lunch and dinner, respectively. The protocol finishes at 9 AM on Day 3. A graphical illustration of the protocol is provided in Fig. 4. The protocol is run on the 10-patient adult cohort of the UVA/Padova Simulator for two scenarios, in which the meals are snacks are announced (Scenario I) and unannounced (Scenario II), respectively. The same sequence of CGM noise is applied in the simulations to enable fair comparison.

Fig. 3:

Architecture of hardware-in-the-loop evaluation.

Fig. 4:

In silico protocols for performance evaluation. The protocols start at 4 PM on Day 1 and end at 9 AM on Day 3. A 75 g CHO dinner accompanied with a 40 g CHO is provided on Day 1. Day 2 features a hypoglycemia challenge together with breakfast, lunch and dinner of [60, 75, 75] g CHO, respectively. The meal boluses are carbohydrate contents of the meals in g-CHO, and the percentages indicate what percent of the meal carbohydrate content is announced.

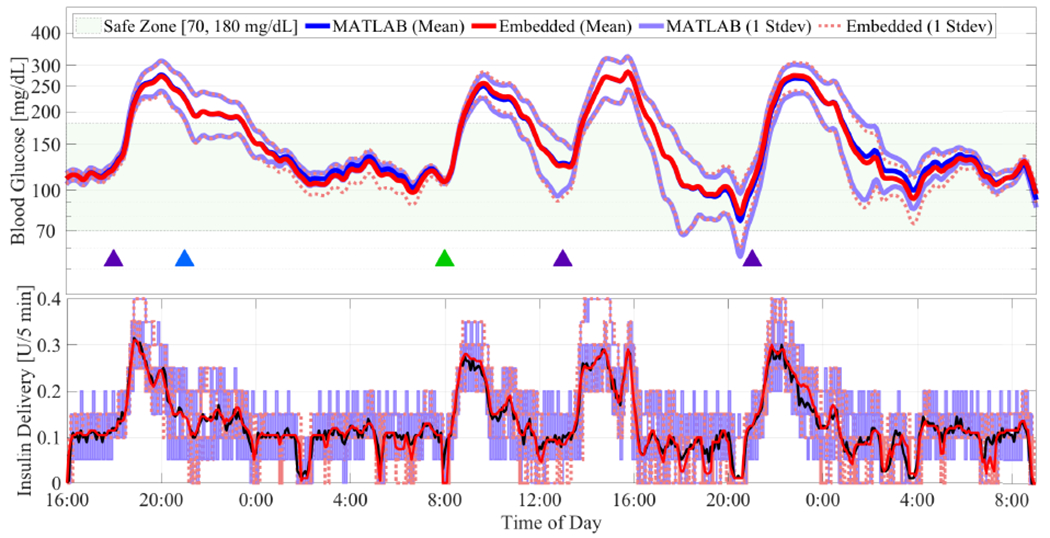

For comparison purposes, we implement the embedded zone MPC using both FAMA and FADMM algorithms. We used one patient from the UVA/Padova patient simulator to tune the solver parameters because this corresponded to 10% data for training using the 10-patient dataset. The FAMA implementation takes up 42 KB flash memory while FADMM implementation needs 56 KB. On average for the subjects, the computation times needed to solve the MPC problem for FAMA and FADMM are 3.93 and 6.64 seconds with standard deviations of 0.28 and 0.69 seconds, respectively; these quantities are relatively agnostic to subject variability. As the code for embedded zone MPC is the same for serial and BLE communication, we only report the results obtained for serial communication. The obtained results are reported in Figs. 5–6 and Table I. The zone-MPC developed in [39] is also evaluated for the same scenarios, the data of which is used as benchmark for performance comparison, and is referred to as “MATLAB”. As identical glucose regulation behavior results are obtained using the FAMA and FADMM algorithms, we refer to these results as “embedded” and do not distinguish them in the remaining analysis.

Fig. 5:

Results for announced meals. Blue, green and purple triangles denote meals of 40 gCHO, 60 gCHO, and 75 gCHO, respectively, and the orange triangle denotes a 2-unit unannounced insulin bolus. The mean values for the 10 patients are plotted using continuous red and blue curves for the embedded zone MPC and the MATLAB-implemented zone MPC proposed in [39], while the corresponding one standard deviations are plotted using dotted red and continuous purple curves.

Fig. 6:

Results for unannounced meals. Keys are the same as Fig. 5.

TABLE I:

Comparison of closed-loop glucose controllers’ performance for announced and unannounced meals. Stat. Eq. represents statistical equivalence, determined using statistical equivalence tests [45].

| Announced Meals | Unannounced Meals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metrics | MATLAB | Embedded | Stat. Eq. | MATLAB | Embedded | Stat. Eq. |

| Mean BG | 136.6 (114.3,123.6) | 137.4 (131.2, 143.6) | ** | 158.2 (149.0,164.7) | 155.0 (148.9, 167.5) | * |

| % time in [70, 180] mg/dL | 83.1 (80.1,89.9) | 84.3 (78.7, 87.4) | * | 66.0 (62.7,73.0) | 66.2 (62.3, 72.6) | * |

| % time < 70 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.6) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.4) | ** | 0.6 (0.0,1.8) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.0) | * |

| % time < 54 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | * |

| % time > 250 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** | 8.3 (2.8,17.8) | 9.0 (2.2, 19.1) | * |

| Total Insulin [U] | 67.9 (60.7,78.6) | 66.1 (61.5, 79.8) | 62.2 (54.7,66.7) | 61.5 (56.6, 66.7) | ||

| BG at 7 AM [mg/dL] | 124.8 (121.0,129.5) | 122.5 (121.0, 129.5) | ** | 126.0 (120.5,127.0) | 118.5 (120.5, 127.0) | ** |

| Night time (11 PM – 7 AM) | ||||||

| Mean BG | 121.2 (114.3,123.6) | 119.0 (114.3, 123.6) | ** | 128.4 (126.9,143.3) | 127.1 (124.2, 140.5) | * |

| % time in [70, 180] mg/dL | 100.0 (96.7,100.0) | 100.0 (95.1, 100.0) | ** | 90.2 (86.1,93.4) | 89.3 (86.1, 93.4) | * |

| % time < 70 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** |

| % time < 54 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** |

| % time > 250 mg/dL | 0.0 (0.0,0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | ** | 0.0 (0.0,5.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 6.6) | * |

| Total Insulin [U] | 10.5 (8.3,13.4) | 10.9 (9.1, 13.5) | ** | 11.2 (9.1,12.9) | 11.2 (9.6, 13.3) | |

Note: Data in this table are shown as median (inter quantile range). Statistical significance is evaluated based on two one-sided equivalence tests and paired Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

The ‘*’ notation denotes statistical equivalence with significance level p < 0.05 and ‘**’ denotes a significance level p < 0.001 (the hypothesis being rejected is that means of both samples are different). Equivalence is only reported when a corresponding difference test rejects the hypothesis, that means of both samples are equal, with a significance level > 0.05.

From Figs. 5–6, we observe that the embedded controller with 32-bit precision behaves quite similarly to the 64-bit version MATLAB controller. This is also confirmed by the metrics in Table I. For each metric, we compared the performance of both the embedded and MATLAB controller and tested statistical equivalence in terms of an equivalence test; see, for example, [45]. Unlike the more common statistical difference tests (like the T-test or the ranksum test), the equivalence test checks the hypothesis that means of the two samples are different; rejection of this hypothesis at some significance level (we consider 0.05) implies equivalence of the two samples with high confidence. For announced meals, comparing glucose metrics in terms of mean BG (137.4 mg/dL vs. 136.6 mg/dL, p = 1.0 × 10−7), percent time in [70, 180] mg/dL (84.3% vs. 83.1%, p = 1.3 × 10−3), and percent time below 70 mg/dL (0.0% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.0) confirms our claim that the two controllers behave identically (from a statistical viewpoint) in closed-loop. For unannounced meals, the mean BG (155.0 mg/dL vs. 158.2 mg/dL, p = 1.5 × 10−3), percent time in [70,180] mg/dL (66.2% vs. 66.0%, p = 2.8 × 10−3), and percent time below 70 mg/dL (0.0% vs. 0.6%, p = 3.7 × 10−2). These quantities validate the performance and effectiveness of the embedded MPC despite the modifications and simplifications introduced to implement the zone MPC on an embedded system, as per international consensus on clinical targets [46]. Interestingly, the total insulin delivered in both cases is smaller for the embedded controller (announced: 66.1 U vs. 67.9 U; unannounced: 61.5 U vs. 62.2 U), although this decreased infusion is not significantly similar, nor significantly different. This can be explained by recalling that the modification made in the embedded controller’s zone specifications is small. This small change results in an improved sensitivity to predicted hypoglycemia, and the embedded controller is seen to shut off insulin infusion faster than the MATLAB controller around 4PM–8PM on the second day in Fig. 6, resulting in a decrease of total insulin infused. We observed that although the glucose and insulin trends are similar in the embedded and full MATLAB implementations, the event-triggering algorithm of [19] results in ≈ 30% reduction of the number of times the QP solver is called to solve the underlying periodic zone MPC control problem, which translates roughly to a 30% reduction in energy expenditure.

V. Conclusions

In this work, an embeddable zone MPC is proposed and implemented on a resource limited hardware platform that emulates a wearable or on-body AP designed to be lightweight and portable. Hardware-in-the-loop experiments using an Arduino Feather M0 on the FDA-approved T1DM simulator indicate that the controller maintains safety and performance for glucose regulation while gaining compatibility with off-the-shelf embedded systems. The developments enable transplantation of AP from mobile computing devices with ample computation and storage capability (e.g., laptops, tablets, mobile phones) to computation/storage resource limited devices, and indicate the feasibility of incorporating glucose feedback control algorithms in on-body health and medical devices. The miniaturization of decision making platforms for the AP has the potential to improve quality of life and glycemic control for people with T1DM.

Acknowledgements

Access to the full version of the UVA/Padova metabolic simulator was provided by an agreement with Prof. C. Cobelli (University of Padova) and Prof. B. P. Kovatchev (University of Virginia) for research purposes. We also thank Dr. R. Gonhalekar and Dr. S. Deshpande for improving discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under awards DP3DK104057 and DP3DK113511.

Contributor Information

Ankush Chakrabarty, Control and Dynamical Systems Group, Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Elizabeth Healey, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

Dawei Shi, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

Stamatina Zavitsanou, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

Francis J. Doyle, III, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

Eyal Dassau, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA.

References

- [1].Zavitsanou S, Chakrabarty A, Dassau E, and Doyle FJ III, “Embedded control in wearable medical devices: application to the artificial pancreas,” Processes, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 35, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnard K, Crabtree V, Adolfsson P, Davies M, Kerr D, Kraus A, Gianferante D, Bevilacqua E, and Serbedzija G, “Impact of type 1 diabetes technology on family members/significant others of people with diabetes,” Journal of diabetes science and technology, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 824–830, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Forlenza GP, Buckingham B, and Maahs DM, “Progress in diabetes technology: developments in insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitors, and progress towards the artificial pancreas,” The Journal of pediatrics, vol. 169, pp. 13–20, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liberman A et al. , “Diabetes technology and the human factor,” Diabetes technology & therapeutics, vol. 18, no. S1, pp. S–101, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kovatchev BP, “Metrics for glycaemic control—from hba 1c to continuous glucose monitoring,” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 425, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Del Favero S et al. , “First use of model predictive control in outpatient wearable artificial pancreas,” Diabetes care, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1212–1215, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Del Favero S, Boscari F, Messori M, Rabbone I, Bonfanti R, Sabbion A, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Visentin R, Calore R et al. , “Randomized summer camp crossover trial in 5-to 9-year-old children: outpatient wearable artificial pancreas is feasible and safe,” Diabetes Care, p. dc152815, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anderson SM et al. , “Multinational home use of closed-loop control is safe and effective,” Diab. Care, vol. 39, no. 7, pp. 1143–1150, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Forlenza GP et al. , “Application of zone model predictive control artificial pancreas during extended use of infusion set and sensor,” Diabetes Care, p. dc170500, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Blauw H, Van Bon A, Koops R, DeVries J, and consortium P, “Performance and safety of an integrated bihormonal artificial pancreas for fully automated glucose control at home,” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 671–677, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].de Bock M et al. , “Exploration of the performance of a hybrid closed loop insulin delivery algorithm that includes insulin delivery limits designed to protect against hypoglycemia,” Journal of diabetes science and technology, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 68–73, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huyett LM, Dassau E, Zisser HC, and Doyle FJ III, “Design and evaluation of a robust PID controller for a fully implantable artificial pancreas,” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, vol. 54, no. 42, pp. 10 311–10 321, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dassau E, Renard E, Place J, Farret A, Pelletier M, Lee J, Huyett LM, Chakrabarty A, Doyle FJ III, and Zisser HC, “Intraperitoneal insulin delivery provides superior glycaemic regulation to subcutaneous insulin delivery in MPC based fully automated artificial pancreas in patients with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study,” Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 1698–1705, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bequette BW, “Algorithms for a closed-loop artificial pancreas: The case for model predictive control,” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1632–1643, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pinsker JE, Lee JB, Dassau E, Seborg DE, Bradley PK, Gondhalekar R, Bevier WC, Huyett L, Zisser HC, and Doyle III FJ, “Randomized crossover comparison of personalized MPC and PID control algorithms for the artificial pancreas,” Diabetes care, vol. 39, no. 7, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Steil GM, “Algorithms for a closed-loop artificial pancreas: the case for proportional-integral-derivative control,” Journal of diabetes science and technology, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1621–1631, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mauseth R, Hirsch IB, Bollyky J, Kircher R, Matheson D, Sanda S, and Greenbaum C, “Use of a “fuzzy logic” controller in a closed-loop artificial pancreas,” Diabetes technology & therapeutics, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 628–633, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chakrabarty A, Zavitsanou S, Doyle III FJ, and Dassau E, “Reducing controller updates via event-triggered model predictive control in an embedded artificial pancreas,” in American Control Conference (ACC), 2017. IEEE, 2017, pp. 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- [19].—, “Event-triggered model predictive control for embedded artificial pancreas systems,” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 575–586, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].—, “Model predictive control with event-triggered communication for an embedded artificial pancreas,” in Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), 2017 IEEE Conference on. IEEE, 2017, pp. 536–541. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Johansen TA, “Toward dependable embedded model predictive control,” IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1208–1219, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Huyck B, Ferreau HJ, Diehl M, De Brabanter J, Van Impe JF, De Moor B, and Logist F, “Towards online model predictive control on a programmable logic controller: Practical considerations,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ding Y, Xu Z, Zhao J, Wang K, and Shao Z, “Embedded MPC Controller Based on Interior-Point Method with Convergence Depth Control,” Asian Journal of Control, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 2064–2077, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Giselsson P, Doan MD, Keviczky T, De Schutter B, and Rantzer A, “Accelerated gradient methods and dual decomposition in distributed model predictive control,” Automatica, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 829–833, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Grancharova A and Olaru S, “Low complexity distributed model predictive control by using contractive sets,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 13164–13169, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dang TV, Ling KV, and Maciejowski JM, “Embedded admm-based qp solver for mpc with polytopic constraints,” in Control Conference (ECC), 2015 European. IEEE, 2015, pp. 3446–3451. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bemporad A, “A quadratic programming algorithm based on nonnegative least squares with applications to embedded model predictive control,” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 1111–1116, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dua P, Kouramas K, Dua V, and Pistikopoulos EN, “MPC on a chip—recent advances on the application of multi-parametric modelbased control,” Computers & Chemical Engineering, vol. 32, no. 4–5, pp. 754–765, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zeilinger MN, Jones CN, and Morari M, “Real-time suboptimal model predictive control using a combination of explicit mpc and online optimization,” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 56, no. 7, pp. 1524–1534, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chakrabarty A, Buzzard GT, Corless MJ, Zak SH, and Rundell AE, “Correcting hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction using observer-based explicit nonlinear model predictive control,” in Proc. of the Int. Conf. on Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE, 2014, pp. 3426–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tøndel P, Johansen TA, and Bemporad A, “An algorithm for multi-parametric quadratic programming and explicit MPC solutions,” Automatica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 489–497, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Quirynen R, Vukov M, Zanon M, and Diehl M, “Autogenerating microsecond solvers for nonlinear MPC: a tutorial using ACADO integrators,” Optimal Control Applications and Methods, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 685–704, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Raha A, Chakrabarty A, Raghunathan V, and Buzzard G, “Ultrafast embedded explicit model predictive control for nonlinear systems,” in Proc. of the American Control Conference, 2017, pp. 4398–4403. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gondhalekar R, Dassau E, Zisser HC, and Doyle III FJ, “Periodiczone MPC for diurnal closed-loop operation of an artificial pancreas,” J. Diab. Sci. Technol, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 1446–1460, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pu Y, Zeilinger MN, and Jones CN, “Fast alternating minimization algorithm for model predictive control,” 19th IFAC World Congress, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 11980–11986, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [36].O’Donoghue B, Stathopoulos G, and Boyd S, “A splitting method for optimal control,” IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 2432–2442, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pu Y, Zeilinger MN, and Jones CN, “Complexity certification of the fast alternating minimization algorithm for linear MPC,” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 888–893, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Grosman B, Dassau E, Zisser HC, Jovanovič L, and Doyle III FJ, “Zone model predictive control: A strategy to minimize hyper- and hypoglycemic events,” J. Diab. Sci. Technol, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 961–975, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gondhalekar R, Dassau E, and Doyle III FJ, “Periodic zone-MPC with asymmetric costs for outpatient-ready safety of an artificial pancreas to treat type 1 diabetes,” Automatica, vol. 71, pp. 237–246, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gondhalekar R, Dassau E, and Doyle III FJ, “Velocity-weighting & velocity-penalty mpc of an artificial pancreas: Improved safety & performance,” Automatica, vol. 91, pp. 105–117, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].van Heusden K, Dassau E, Zisser HC, Seborg DE, and Doyle III FJ, “Control-relevant models for glucose control using a priori patient characteristics,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 1839–1849, July 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ellingsen C, Dassau E, Zisser H, Grosman B, Percival MW, Jovanovič L, and Doyle III FJ, “Safety constraints in an artificial pancreatic β cell,” J. Diab. Sci. Tech, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 536–544, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Goldstein T, O’Donoghue B, Setzer S, and Baraniuk R, “Fast alternating direction optimization methods,” SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 1588–1623, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dalla Man C et al. , “The uva/padova type 1 diabetes simulator: new features,” J. Diab. Sci. Technol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 26–34, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mecklin CJ, “A Comparison Of Equivalence Testing In Combination With Hypothesis Testing And Effect Sizes,” Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 329–340, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Battelino T et al. , “Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range,” Diabetes care, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1593–1603, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]