Abstract

Background:

The period shortly after hospitalization for heart failure (HF) represents a high-risk window for recurrent clinical events, including rehospitalization or death.

Objectives:

To determine whether the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan varies in relation to the proximity to HF hospitalization among patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Methods:

In this post hoc analysis of PARAGON-HF, we assessed risk of clinical events and response to sacubitril/valsartan in relation to time from last HF hospitalization among patients with HFpEF (≥45%). Primary outcome was composite total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death, analyzed using a semiparametric proportional rates method, stratified by geographic region.

Results:

Of 4,796 validly randomized patients in PARAGON-HF, 622 (13%) were screened during hospitalization or within 30 days of prior hospitalization, 555 (12%) within 31–90 days, 435 (9%) within 91–180 days, 694 (14%) after 180 days, and 2,490 (52%) were never previously hospitalized. Over median 35 months follow-up, risk of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death was inversely and non-linearly associated with timing from prior HF hospitalization (P<0.001). There was a gradient in relative risk reduction in primary events with sacubitril/valsartan from patients hospitalized within 30 days (rate ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.53–0.99) to patients never hospitalized (rate ratio 1.00; 95% confidence interval 0.80–1.24); trend in relative risk reduction Pinteraction=0.15. With valsartan alone, rate of total primary events was 26.7 (≤30 days), 24.2 (31–90 days), 20.7 (91–180 days), 15.7 (>180 days), and 7.9 (not previously hospitalized) per 100 patient-years. Compared with valsartan, absolute risk reductions with sacubitril/valsartan were more prominent in patients enrolled early after hospitalization: 6.4% (≤30 days), 4.6% (31–90 days), 3.4% (91–180 days), while no risk reduction was observed in patients screened >180 days or who were never hospitalized; trend in absolute risk reduction Pinteraction=0.050.

Conclusions:

Recent hospitalization for HFpEF identifies patients at high-risk for near-term clinical progression. In the PARAGON-HF trial, relative and absolute benefits of sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan in HFpEF appear to be amplified when initiated in the high-risk window after hospitalization and warrants prospective validation.

Keywords: clinical outcomes, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, hospitalization, sacubitril/valsartan

CONDENSED ABSTRACT:

In this post hoc analysis of 4,796 randomized patients with chronic HFpEF (≥45%) in the PARAGON-HF trial, over median 35 months follow-up, risk of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death was inversely and non-linearly associated with timing from prior HF hospitalization (P<0.001). Sacubitril/valsartan vs. valsartan alone was associated with a numerical gradient of risk reduction ranging from patients hospitalized within 30 days (rate ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.53–0.99) to patients never hospitalized (rate ratio 1.00; 95% confidence interval 0.80–1.24); trend in relative risk reduction Pinteraction=0.15. With sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute risk reductions were 6.4% (≤30 days), 4.6% (31–90 days), 3.4% (91–180 days), respectively, while no risk reduction was observed in patients screened >180 days or who were never hospitalized (trend in absolute risk reduction Pinteraction=0.050). Relative and absolute benefits of sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan in HFpEF appear to be amplified when initiated in the high-risk window after hospitalization and warrants prospective validation.

Introduction

Hospitalization is a perturbational event in the clinical course of patients with heart failure (HF); the period shortly after hospitalization represents a high-risk window for recurrent clinical events, including rehospitalization or death (1,2). Patients with recurrent readmissions for HF disproportionately contribute to healthcare costs and resource utilization (3). Therapies initiated during or soon after hospitalization are associated with higher post-discharge use in follow-up (4–6). The angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor, sacubitril/valsartan, when initiated during hospitalization for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) was safe and led to short-term reductions in natriuretic peptides (4) and clinical events (7) compared with enalapril. Expert consensus statements endorse a strategy of in-hospital initiation of or switching to sacubitril/valsartan among patients with HFrEF (8,9).

In contrast to HFrEF, there has been limited therapeutic progress for patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Recently, however, use of sacubitril/valsartan was associated with modest reductions in the risk of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death compared with valsartan alone in ambulatory patients with HFpEF enrolled in the PARAGON-HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB Global Outcomes in HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction) trial (rate ratio 0.87, 95% confidence interval 0.75 to 1.005; P=0.058) (10).

Key challenges in the design of clinical trials for HFpEF are disease heterogeneity and the confounding of HF diagnosis by comorbid medical illness. Recent hospitalization for HF management may identify patients with objective evidence of congestion who are at higher risk of disease progression and may have a more modifiable HFpEF phenotype. PARAGON-HF permitted screening during hospitalization for HFpEF, and nearly half of enrolled patients were previously hospitalized. In this post hoc analysis of the PARAGON-HF, we determined whether the risk of clinical events and response to sacubitril/valsartan varies in relation to the proximity to HF hospitalization or the burden of HF hospitalizations in the prior year.

METHODS

PARAGON-HF Design.

The design (11) and principal results (10) of PARAGON-HF have been previously reported. In brief, PARAGON-HF was a randomized, double-blind comparison of sacubitril/valsartan with valsartan in patients ≥50 years of age with chronic HF, left ventricular ejection fraction ≥45% within the 6 months prior to screening, New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms, elevated natriuretic peptides, evidence of structural heart disease (left atrial enlargement or left ventricular hypertrophy), and use of diuretics for at least 30 days. If patients were not recently hospitalized for HF (within 9 months), N-terminal-pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was required to be >300pg/mL (or >900pg/mL if in atrial fibrillation on screening electrocardiogram). If patients had been hospitalized, NT-proBNP>200pg/mL (or >600pg/mL for atrial fibrillation) was required. While patients were allowed to be screened during hospitalization, randomization during an episode of acute decompensated HF was not permitted. Patients meeting all study eligibility criteria entered single-blind run-in periods with valsartan and sacubitril/valsartan (both at half-target doses) to determine tolerability of both study drugs; those successfully completing the run-in period without adverse effects were subsequently randomized 1:1 to receive sacubitril/valsartan (target dose, 97mg/103mg twice daily) or valsartan (target dose, 160mg twice daily). All patients provided written informed consent to participate and study protocols were approved by the ethics committees and local institutional review boards at participating sites.

Clinical Endpoints.

The primary study outcome was the composite of total (first and recurrent) HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death. Time-to-first event of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death was a prespecified secondary endpoint. The key safety endpoint for this analysis was drug discontinuation due to a serious adverse event. Clinical events including all deaths and HF hospitalizations were adjudicated by a Clinical Events Committee blinded to study drug assignment (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA).

Timing of Prior HF Hospitalizations.

As study eligibility was influenced by presence and timing of prior HF hospitalization, it was characterized with limited missingness by site investigators. Timing and number of prior HF hospitalizations were based on patient and caregiver recall, and medical record corroboration, when available. Timing of prior hospitalization for HF to screening was categorized as ≤30 days, 31–90 days, 91–180 days, >180 days, or never previously hospitalized. In cases in which only the month of the prior hospitalization was known, the date was imputed to the 1st of the month. If only the year of hospitalization was known, then the date was imputed as the 1st of January. Three patients with unknown month, date, and year of hospitalization were assigned to the modal category (>180 days). Patients screened during hospitalization or randomized on the day of discharge were included in the 0–30 days category. In sensitivity analysis, given variable time from screening to randomization (Supplemental Figure 1), we separately analyzed total time from prior HF hospitalization to randomization (instead of screening). Number of prior HF hospitalizations within the last year were categorized as 0, 1, or >1.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed in the intention-to-treat cohort. Baseline characteristics and clinical endpoints were assessed across categories defined by timing from prior hospitalization and number of recent HF hospitalizations. We evaluated the association between timing from prior HF hospitalization and number of recent HF hospitalizations and clinical outcomes in 3 models: 1) unadjusted; 2) adjusted for select covariates determined a priori (age, sex, ejection fraction, and natriuretic peptides); and 3) adjusted for all listed baseline covariates different at P<0.10. Treatment effects of sacubitril/valsartan vs. valsartan were assessed within each category for the primary efficacy endpoint (analyzed using both recurrent and time-to-first analyses) and drug discontinuation due to a serious adverse event. As prespecified in the PARAGON-HF protocol (11), for recurrent event analyses, the primary composite endpoint was analyzed using a semiparametric proportional rates method developed by Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (12), stratified according to geographic region. Rate ratios represented total number of events over total exposure time with confidence intervals based on Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators. Interaction testing was performed to determine if the relative or absolute treatment effects of sacubitril/valsartan vs. valsartan varied as a linear trend across ordered groups defined by time since HF hospitalization and number of recent HF hospitalizations. We further evaluated timing of prior HF hospitalization as a continuous measure (log-transformed given skew) using restricted cubic splines with treatment effect rate ratio estimated using a negative binomial model. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate treatment effects for time-to-first events. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to display time-to-first HF hospitalization or cardiovascular death by these groups and compared using log-rank tests. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

From July 2014 to December 2016, 4,822 patients were randomized across 788 centers in 43 countries. Twenty-six patients were excluded due to enrollment from a site with violations of Good Clinical Practice. Of the 4,796 validly randomized patients, 2,306 (48%) were previously hospitalized a mean of 256 ± 573 days and a median of 86 days (25th-75th percentile 27–221) days prior to screening.

Clinical Profile.

Overall, 622 (13%) were screened during hospitalization or within 30 days of prior hospitalization, 555 (12%) within 31–90 days, 435 (9%) within 91–180 days, 694 (14%) after 180 days, and 2,490 (52%) were never previously hospitalized. Patients who were randomized shortly after hospital discharge were more likely to be younger, have higher heart rates and prevalence of atrial fibrillation, and were more frequently treated with diuretics and β-blockers (P<0.01 for all; Table 1). Left ventricular ejection fraction significantly varied across groups (P=0.006), but these differences were not clinically meaningful (mean ~57–58% across groups).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Time from Prior of Hospitalization for HF to Screening in PARAGON-HF

| Time from Last Hospitalization for HF to Screening | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 days (n=622) | 31–90 days (n=555) | 91–180 days (n=435) | >180 days (n=694) | No Prior HF Hosp (n=2,490) | P for trend | |

| Randomization to Sacubitril/Valsartan (%) | 308 (49.5%) | 281 (50.6%) | 218 (50.1%) | 328 (47.3%) | 1272 (51.1%) | 0.56 |

| Age (years) | 71.6 ± 9.0 | 71.6 ± 8.8 | 72.2 ± 8.6 | 72.4 ± 8.5 | 73.5 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 333 (53.5%) | 283 (51.0%) | 203 (46.7%) | 294 (42.4%) | 1366 (54.9%) | 0.15 |

| Race | 0.08 | |||||

| Asian | 95(15.3%) | 80(14.4%) | 56(12.9%) | 84(12.1%) | 292 (11.7%) | |

| Black | 12(1.9%) | 19(3.4%) | 9 (2.1%) | 14(2.0%) | 48(1.9%) | |

| Other | 13(2.1%) | 17(3.1%) | 22(5.1%) | 20(2.9%) | 108 (4.3%) | |

| White | 502 (80.7%) | 439 (79.1%) | 348 (80.0%) | 576 (83.0%) | 2042 (82.0%) | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||||

| Asia/Pacific and Other | 119 (19.1%) | 107 (19.3%) | 70(16.1%) | 117 (16.9%) | 349 (14.0%) | |

| Central Europe | 302 (48.6%) | 191 (34.4%) | 149 (34.3%) | 220 (31.7%) | 853 (34.3%) | |

| Latin America | 41(6.6%) | 27(4.9%) | 30(6.9%) | 51(7.3%) | 221 (8.9%) | |

| North America | 43(6.9%) | 92(16.6%) | 50(11.5%) | 90(13.0%) | 284 (11.4%) | |

| Western Europe | 117 (18.8%) | 138 (24.9%) | 136 (31.3%) | 216 (31.1%) | 783 (31.4%) | |

| Baseline NT-proBNP (median IQR) | 891 [425–1784] | 843 [388–1779] | 836 [381–1597] | 948 [478–1717.5] | 930 [489–1529.5] | 0.16 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 4.9 | 30.5 ± 5.1 | 30.1 ± 5.1 | 30.8 ± 5.1 | 30.0 ± 4.9 | 0.06 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 131 ± 15 | 130.5 ± 16 | 132 ± 16 | 130 ± 16 | 130 ± 15 | 0.32 |

| Heart rate (bpm)* | 72 ± 13 | 72 ± 12.5 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Third heart sound | 8 (1.3%) | 17 (3.1%) | 13 (3.0%) | 14 (2.0%) | 59 (2.4%) | 0.54 |

| Rales | 44 (7.1%) | 46 (8.3%) | 34 (7.8%) | 47 (6.8%) | 174 (7.0%) | 0.50 |

| Edema | 195 (31.5%) | 211 (38.0%) | 185 (42.5%) | 269 (38.8%) | 966 (38.8%) | 0.01 |

| Jugular venous distension | 70 (11.4%) | 77 (13.9%) | 68 (15.7%) | 116 (17.0%) | 324 (13.1%) | 0.64 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 57.1 ± 8.0 | 57.5 ± 7.8 | 56.9 ± 7.8 | 56.9 ± 7.7 | 57.9 ± 7.9 | 0.006 |

| New York Heart Association Class (%) | 0.13 | |||||

| 1 | 31 (5.0%) | 25 (4.5%) | 12 (2.8%) | 18 (2.6%) | 51 (2.0%) | |

| 2 | 451 (72.6%) | 406 (73.2%) | 334 (76.8%) | 520 (74.9%) | 1995 (80.2%) | |

| 3 | 134 (21.6%) | 123 (22.2%) | 84(19.3%) | 151 (21.8%) | 440 (17.7%) | |

| 4 | 5 (0.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (1.1%) | 5 (0.7%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| History of stroke (%) | 81(13.0%) | 58(10.5%) | 38(8.8%) | 86(12.4%) | 245 (9.9%) | 0.09 |

| History of myocardial infarction (%) | 134 (21.5%) | 123 (22.2%) | 107 (24.6%) | 175 (25.2%) | 544 (21.8%) | 0.94 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 230 (37.0%) | 189 (34.1%) | 142 (32.8%) | 238 (34.3%) | 753 (30.4%) | <0.001 |

| Diuretic (%) | 606 (97.4%) | 533 (96.0%) | 420 (96.6%) | 680 (98.0%) | 2346 (94.2%) | <0.001 |

| ACEi or ARB (%) | 547 (87.9%) | 473 (85.2%) | 358 (82.3%) | 596 (85.9%) | 2165 (86.9%) | 0.67 |

| β-blocker | 519 (83.4%) | 459 (82.7%) | 325 (74.7%) | 561 (80.8%) | 1957 (78.6%) | 0.008 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (%) | 186 (29.9%) | 163 (29.4%) | 140 (32.2%) | 241 (34.7%) | 509 (20.4%) | <0.001 |

| Digoxin (%) | 57 (9.2%) | 59 (10.6%) | 54 (12.4%) | 69 (9.9%) | 211 (8.5%) | 0.13 |

Baseline heart rate irrespective of presenting rhythm

Abbreviations: ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; HF = heart failure; NT-proBNP = N-terminal prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide

Three patients with a history of prior HF hospitalization had missing dates of prior hospitalization, and were imputed to the modal category (>180 days)

Clinical Outcomes.

Over median 35 months (interquartile range 30–41) follow-up, there were 1,083 first primary endpoints, 1,903 total primary endpoints, and 658 drug discontinuations due to a serious adverse event. Risk of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death was inversely and non-linearly associated with timing from prior HF hospitalization (P<0.001 for overall trend; P=0.03 for non-linearity). Shorter times from prior HF hospitalization were associated with higher risk of recurrent primary events, independent of key covariates (Table 2) and after more extensive covariate adjustment (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes & Treatment Response to Sacubitril/Valsartan vs. Valsartan by Timing from Prior Hospitalization

| Recurrent Primary Events | ||||||

| Time from Prior Hospitalization to Screening | N | Total Events | Rate (per 100 p-y) | Unadjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Rate Ratio (95% CI)* | Treatment Effect (Sac/Val vs. Val) |

| ≤ 30 days | 622 | 414 | 23.5 (20.0–27.6) | 3.28 (2.69–4.00) | 3.21 (2.63–3.92) | 0.73 (0.53–0.99) |

| 31–90 days | 555 | 358 | 21.9 (17.9–26.8) | 2.59 (2.05–3.26) | 2.61 (2.08–3.27) | 0.82 (0.56–1.19) |

| 91–180 days | 435 | 244 | 19.0 (15.5–23.3) | 2.39 (1.91–2.99) | 2.41 (1.92–3.02) | 0.87 (0.59–1.27) |

| >180 days | 694 | 316 | 15.8 (13.4–18.8) | 1.93 (1.58–2.36) | 1.88 (1.53–2.32) | 0.93 (0.66–1.30) |

| Never Hospitalized | 2490 | 571 | 7.9 (7.1–8.9) | Ref | Ref | 1.00 (0.80–1.24) |

| Pinteraction =0.15 | ||||||

| All PARAGON-HF Participants | 4796 | 1903 | 13.7 (12.7–14.7) | -- | -- | 0.87 (0.75–1.005) |

| Time-to-First Primary Events | ||||||

| Time from Prior Hospitalization to Screening | N | First Events | Incident Rate (per 100 p-y) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | Treatment Effect (Sac/Val vs. Val) |

| ≤ 30 days | 622 | 214 | 14.3 (12.5–16.4) | 2.64 (2.23–3.13) | 2.66 (2.24–3.16) | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) |

| 31–90 days | 555 | 168 | 11.9 (10.3–13.9) | 1.96 (1.63–2.36) | 2.04 (1.69–2.46) | 0.97 (0.72–1.32) |

| 91–180 days | 435 | 127 | 11.4 (9.5–13.5) | 1.98 (1.63–2.41) | 2.06 (1.69–2.52) | 0.97 (0.69–1.37) |

| >180 days | 694 | 176 | 9.9 (8.5–11.4) | 1.66 (1.39–1.98) | 1.61 (1.35–1.93) | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) |

| Never Hospitalized | 2490 | 398 | 5.8 (5.3–6.4) | Ref | Ref | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) |

| Pinteraction =0.22 | ||||||

| All PARAGON-HF Participants | 4796 | 1083 | 8.6 (8.1–9.1) | -- | -- | 0.92 (0.81–1.03) |

| Study Drug Discontinuation Due to Serious AE | ||||||

| Time from Prior Hospitalization to Screening | N | Total Events | Incident Rate (per 100 p-y) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | Treatment Effect (Sac/Val vs. Val) |

| ≤ 30 days | 622 | 89 | 5.7 (4.6–7.0) | 1.19 (0.94–1.50) | 1.22 (0.96–1.54) | 0.73 (0.48–1.12) |

| 31–90 days | 555 | 86 | 6.0 (4.9–7.5) | 1.20 (0.95–1.53) | 1.26 (0.99–1.60) | 0.79 (0.52–1.20) |

| 91–180 days | 435 | 65 | 5.7 (4.4–7.2) | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) | 1.17 (0.90–1.53) | 1.06 (0.66–1.70) |

| >180 days | 694 | 93 | 5.2 (4.3–6.4) | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 1.07 (0.71–1.60) |

| Never Hospitalized | 2490 | 325 | 5.1 (4.6–5.7) | Ref | Ref | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) |

| Pinteraction =0.17 | ||||||

| All PARAGON-HF Participants | 4796 | 658 | 5.3 (5.0–5.8) | -- | -- | 0.94 (0.81–1.09) |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse events; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio

Adjusted for age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, and log-transformed N-terminal prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide, and stratified by geographic region

The primary composite endpoint was analyzed using a semiparametric proportional rates method developed by Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying. All models were stratified by geographic region.

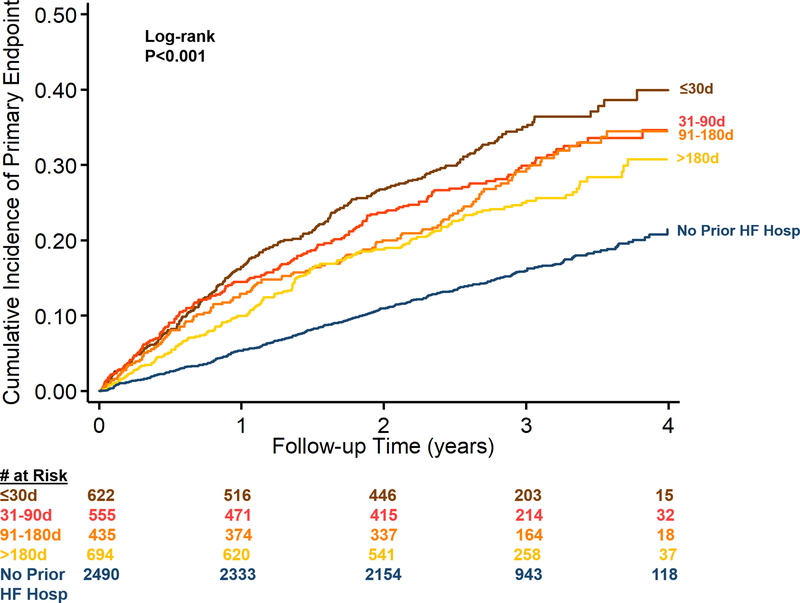

Rates of the first primary endpoints similarly were highest among patients screened within 30 days of hospitalization (14.3[12.5–16.4] per 100 patient-years) and decreased with longer time from last hospitalization. The lowest rates of first primary endpoints were observed among patients without prior HF hospitalization (5.8 [5.3–6.4] per 100 patient-years); Figure 1. In contrast, rates of study drug discontinuation did not vary by timing of prior HF hospitalization with an overall incidence rate of 5.3 (5.0–5.8) per 100 patient-years (Table 2).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis for time-to-first primary endpoints relative to timing from prior HF hospitalization.

Survival curves were compared by log-rank testing. Abbreviations: HF = heart failure

Treatment Response to Sacubitril/Valsartan vs. Valsartan.

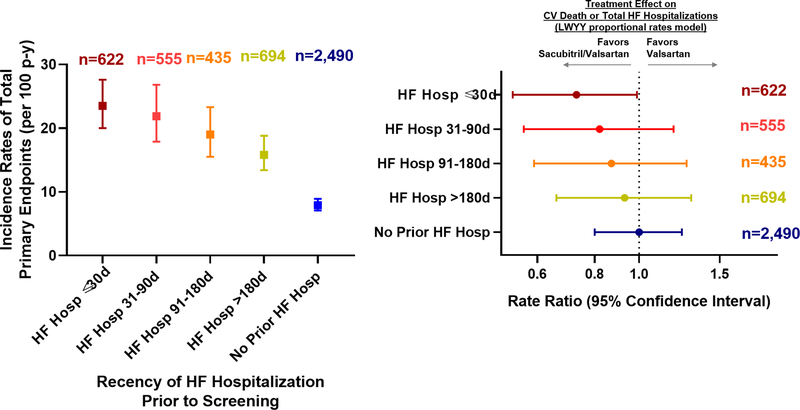

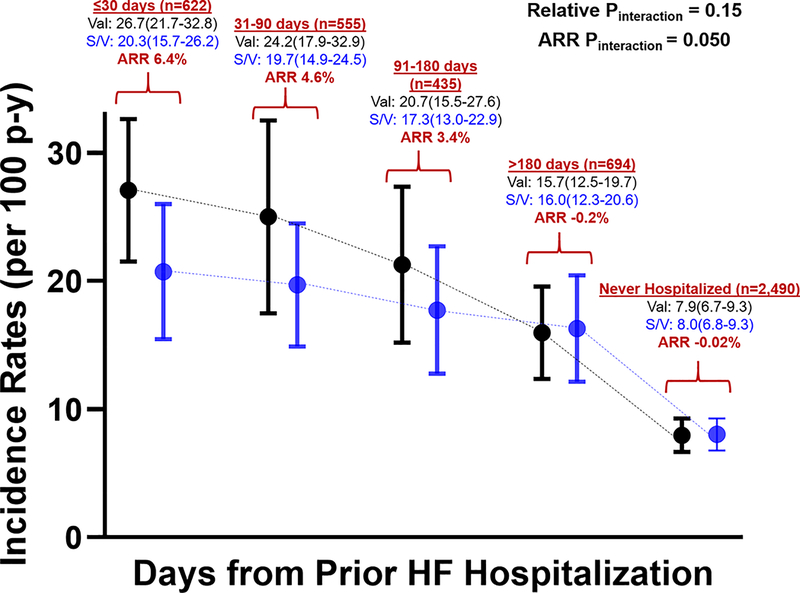

The effect of sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan on total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death was greatest among patients screened during or shortly after hospitalization. There was a numerical gradient of risk reduction ranging from patients hospitalized within 30 days (rate ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.53–0.99) to patients never hospitalized (rate ratio 1.00; 95% confidence interval 0.80–1.24); Pinteraction=0.15 for trend in relative treatment effects (Figure 2). With valsartan alone, rate of total primary events was 26.7 (≤30 days), 24.2 (31–90 days), 20.7 (91–180 days), 15.7 (>180 days), and 7.9 (not previously hospitalized) per 100 patient-years. With sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute risk reductions were 6.4% (≤30 days), 4.6% (31–90 days), 3.4% (91–180 days), −0.2% (>180 days), and −0.02% (never hospitalized); Pinteraction=0.050 for trend in absolute risk reduction (Figure 3, Central Illustration). Sensitivity analyses confirmed similar findings when time from prior HF hospitalization to randomization (instead of screening) was analyzed (Supplemental Table 2). Similar results were also observed when time from prior hospitalization was analyzed as a continuous measure (Supplemental Figure 2) and in the evaluation of time-to-first primary endpoints (Supplemental Figure 3). Sacubitril/valsartan had similar risk of drug discontinuation due to a serious adverse event as valsartan, irrespective of timing of initiation relative to prior history of HF; Table 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of treatment effects of sacubitril/valsartan versus valsartan on the primary endpoint (total HF hospitalizations and CV death) by timing from prior HF.

Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals are displayed. The primary composite endpoint was analyzed using a semiparametric proportional rates method developed by Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (LWYY), stratified by geographic region. Abbreviations: CV = cardiovascular; HF = heart failure; p-y = patient-years

Figure 3 (Central Illustration). Incidence rates of total primary endpoints in sacubitril/valsartan and valsartan alone treatment arms by groups categorized by time from prior HF hospitalization.

All incidence rates are expressed per 100 patient-years. Abbreviations: ARR = absolute risk reduction; HF = heart failure; p-y = patient-years; S/V = sacubitril/valsartan; V = valsartan

Prior HF Hospitalization Burden.

Overall, 284 (6%) patients had 2 or more hospitalizations in the prior 12 months, 1,746 (36%) had 1 HF hospitalization in the prior 12 months, and 276 (6%) were hospitalized >12 months prior to screening (Supplemental Table 3). Compared to those with fewer hospitalizations within the prior 12 months, patients with 2 or more HF hospitalizations in the last 12 months faced the highest rates of either first or total primary composite endpoints (Supplemental Table 4). There was a gradient of response to sacubitril/valsartan in reducing total primary events from patients who had 2 or more HF hospitalizations in the last 12 months (rate ratio: 0.63; 95% confidence interval 0.41–0.97) to patients with 1 recent HF hospitalization (rate ratio: 0.89; 95% confidence interval 0.72–1.09) to patients with remote HF hospitalization (rate ratio: 0.89; 95% confidence interval 0.51–1.54) to patients who had not been previously hospitalized (rate ratio 1.00; 95% confidence interval 0.80–1.24); Pinteraction=0.12 for trend in relative treatment effects (Supplemental Table 4). With sacubitril/valsartan, the absolute risk reductions were 14.8% (≥2 hospitalizations in last 12 months), 2.2% (1 hospitalization in last 12 months), 1.1% (hospitalization remotely >12 months prior to screening), while no risk reduction was observed in patients who were never hospitalized (Pinteraction=0.050 for trend in absolute risk reduction).

DISCUSSION

In this post hoc analysis of the PARAGON-HF trial, we found that patients with HFpEF who were recently hospitalized, and particularly those with multiple recent hospitalizations, face 2–3-fold higher risks of rehospitalization and cardiovascular death. In contrast, patients who have never required hospitalization experience more modest rates of clinical events. There was a gradient in observed relative treatment effects with sacubitril/valsartan ranging from patients who were recently hospitalized within 30 days (~25–30% risk reduction) to patients never hospitalized (with point estimates centered around unity), and the same pattern was seen with respect to absolute risk reductions. Patients with recent HF hospitalizations experienced comparable rates of drug discontinuation due to serious adverse events. Taken together, these data suggest that recent HF hospitalization identifies HFpEF patients at enriched risk for adverse outcomes that may be modifiable with sacubitril/valsartan.

The diagnosis of HFpEF is challenging to affirm in the ambulatory setting. Misattribution of non-specific symptoms (such as dyspnea) (13), challenges with the physical examination (due to adiposity, venous stasis, and chronic lung diseases) (14), and variable, comorbidity-dependent markers of disease (natriuretic peptide levels) (15) all add to diagnostic complexity. Requirement for HF hospitalization has traditionally been employed as one of several key eligibility criteria in clinical trials to enrich patient risk and to add certainty to a HFpEF diagnosis.

In PARAGON-HF, approximately half of patients carried a history of prior HF hospitalization. Consistent with prior trial experiences of HFpEF (16–18), more recent HF hospitalization events are associated with subsequent event rates that approach or exceed those observed in ambulatory patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction. Indeed, event rates after HF hospitalization are nearly identical regardless of ejection fraction (16,19). While appealing as a key eligibility criteria in HF trials, thresholds for inpatient hospitalization vary globally, especially across different resource settings (20,21). However, even after stratifying all models by region of enrollment (as specified by the trial protocol), HF hospitalization remained a globally relevant and prognostically important event which should continue to be considered in contemporary clinical trials.

Our data suggest that timing of prior HF hospitalization may influence treatment effects of sacubitril/valsartan. Mechanistically, excess neurohormonal and neprilysin pathway activation, targeted by sacubitril/valsartan, may be pronounced in the vulnerable phase after hospital discharge (22). Indeed, in a small experience of patients with acute decompensated HF, soluble neprilysin levels appear to remain stably elevated even after decongestion and clinical compensation (23). Beyond the direct renin-angiotensin-system and neprilysin effects, sacubitril/valsartan may also further attenuate residual congestion in patients during or soon after hospitalization. In patients hospitalized with HFrEF, sacubitril/valsartan rapidly lowered natriuretic peptide levels and improved HF-related clinical events, suggesting potential early hemodynamic and decongestive effects (4). Overall, patients with HFpEF identified early after hospitalization have pathophysiological mechanisms of disease progression that may be more modifiable with inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-system and neprilysin pathways.

Clinical Implications.

Initiation or switching to sacubitril/valsartan during hospitalization for HFrEF is now endorsed by expert consensus documents (8,9). Introduction of therapies surrounding a HF event is appealing in that the inpatient period allows for engagement in patient counseling, rapid uptitration, and close hemodynamic, laboratory, and symptom monitoring (24). Inpatient initiatives target high-risk patients for recurrent readmission and clinical progression. Fluctuations in hemodynamics, renal function, and electrolytes commonly occur during the transition phase to the ambulatory setting raising potential for safety concerns with new therapeutics. Despite these potential hazards, sacubitril/valsartan was not associated with excess drug discontinuation compared with valsartan among high-risk patients with HFpEF early after hospitalization.

Study Limitations

This analysis examining differential response to sacubitril/valsartan by prior HF hospitalization status was post hoc and non-prespecified, thus should be considered hypothesis-generating. PARAGON-HF was not designed to assess effect modification by history of HF hospitalization; these analyses and interaction terms may be underpowered. The eligibility criteria and run-in periods employed in the PARAGON-HF trial limit the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusions

Nearly half of patients with HFpEF enrolled in PARAGON-HF had a history of prior HF hospitalization, of whom a quarter were screened during or within 30 days of hospitalization. Recent HF hospitalization represents a risk predictor of recurrent clinical events and potentially identifies a group of patients with HFpEF who might be particularly responsive to sacubitril/valsartan. These data suggest that sacubitril/valsartan may blunt excess risk conferred in the high-risk post-discharge period and provide a rationale for further trials that assess sacubitril/valsartan in recently hospitalized HFpEF patients. If these findings are replicated, then sacubitril/valsartan may represent an important strategy to disrupt high disease burden and resource utilization among patients recently hospitalized for HF.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

Competency in Medical Knowledge:

Recent hospitalization for HFpEF identifies patients at high-risk for near-term clinical progression who may have amplified benefit from sacubitril/valsartan to decrease risk of rehospitalization or cardiovascular death.

Translational Outlook:

These hypothesis-generating data suggest that sacubitril/valsartan may blunt excess risk conferred in the high-risk post-discharge period and provide a rationale for further trials that assess sacubitril/valsartan in recently hospitalized HFpEF patients.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The PARAGON-HF trial is funded by Novartis.

Disclosures

Dr. Vaduganathan is supported by the KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst (NIH/NCATS Award UL 1TR002541) and serves on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Relypsa.

Dr. Claggett has received consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, AOBiome, and Corvia.

Dr. Desai has received research grant support from AstraZeneca, Alnylam, and Novartis and consulting fees and/or honoraria from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Alnylam, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Biofourmis, Corvidia, DalCor Pharma, Novartis, Relypsa, and Regeneron.

Dr. Anker reports grants from Vifor International and Abbott Vascular. He also personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brahms GmbH, Impulse Dynamics, Novartis, Servier, St. Jude Medical, and Vifor International.

Dr. Perrone has received fees from Novartis for conferences, clinical research programs, and to integrate an advisory group.

Dr. Janssens has received research grants from Novartis and has a consultancy agreement with Novartis through the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Dr. Milicic has lectured and consulted for Novartis.

Dr. Arango has received funds for clinical studies and has consulted for Novartis.

Dr. Packer has received personal fees from Akcea, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Actavis, Abbvie, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardiorentis, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Synthetic Biologics, and Theravance.

Drs. Shi & Lefkowitz are employees of Novartis.

Dr. McMurray has served as an executive committee member and coprincipal investigator of ATMOSPHERE and coprincipal investigator of the PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF trials; and his employer, Glasgow University, has been paid by Novartis for his time spent in these roles.

Dr. Solomon has received research grants from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Celladon, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis Pharmaceutics, Lone Star Heart, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and has consulted for Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvia, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ironwood, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and Theracos.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ARNI

Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal-pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- PARAGON-HF

Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB Global Outcomes in HFpEF

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: PARAGON-HF: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01920711

Tweet: New #PARAGONHF data at #AHA19: HFpEF pts early after hospitalization face ↑ HF events & may respond favorably to sacubitril/valsartan

References

- 1.Vaduganathan M, Bonow RO, Gheorghiade M. Thirty-day readmissions: the clock is ticking. JAMA 2013;309:345–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai AS, Claggett BL, Packer M et al. Influence of Sacubitril/Valsartan (LCZ696) on 30-Day Readmission After Heart Failure Hospitalization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David G, Smith-McLallen A, Ukert B. The effect of predictive analytics-driven interventions on healthcare utilization. J Health Econ 2019;64:68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD et al. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2019;380:539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattis WA, O’Connor CM, Gallup DS et al. Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT-HF) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mentz RJ, et al. Poster No. 252. Presented at: AHA Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Scientific Sessions; April 5-6, 2019; Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow DA, Velazquez EJ, DeVore AD et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Randomly Assigned to Sacubitril/Valsartan or Enalapril in the PIONEER-HF Trial. Circulation 2019;139:2285–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollenberg SM, Warner Stevenson L et al. 2019 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Risk Assessment, Management, and Clinical Trajectory of Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD et al. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS et al. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon SD, Rizkala AR, Gong J et al. Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Rationale and Design of the PARAGON-HF Trial. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin DW, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J R Stat Soc B 2000; 62: 711–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramalho SHR, Santos M, Claggett B et al. Association of Undifferentiated Dyspnea in Late Life With Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Dysfunction: A Cross-sectional Analysis From the ARIC Study. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e195321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvaraj S, Claggett B, Shah SJ et al. Utility of the Cardiovascular Physical Examination and Impact of Spironolactone in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2019;12:e006125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myhre PL, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL et al. Association of Natriuretic Peptides With Cardiovascular Prognosis in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Secondary Analysis of the TOPCAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:1000–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bello NA, Claggett B, Desai AS et al. Influence of previous heart failure hospitalization on cardiovascular events in patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desai AS, Claggett B, Pfeffer MA et al. Influence of hospitalization for cardiovascular versus noncardiovascular reasons on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure across the spectrum of ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S et al. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2007;116:1482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA et al. Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2476–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewan P, Rorth R, Jhund PS et al. Income Inequality and Outcomes in Heart Failure: A Global Between-Country Analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene SJ, Hernandez AF, Sun JL et al. Relationship Between Enrolling Country Income Level and Patient Profile, Protocol Completion, and Trial End Points. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Vaduganathan M, Khan SS, Butler J, Gheorghiade M. The vulnerable phase after hospitalization for heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahama H, Minamino N, Izumi C. Plasma soluble neprilysin levels are unchanged during recovery after decompensation of heart failure: a matter of the magnitude of the changes in systemic haemodynamics? Eur Heart J 2018;39:3472–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhagat AA, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Butler J. Initiation, Continuation, Switching, and Withdrawal of Heart Failure Medical Therapies During Hospitalization. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.