Abstract

Background:

Skilled delivery reduces maternal and neonatal mortality. Ghana has put in place measures to reduce geographical and financial access to skilled delivery. Despite this, about 30% of deliveries still occur either at home or are conducted by traditional birth attendants. We, therefore, conducted this study to explore the reasons for the utilization of the services of traditional birth attendants despite the availability of health facilities.

Method:

Using a phenomenology study design, we selected 31 women who delivered at facilities of four traditional birth attendants in the Northern region of Ghana. Purposive sampling was used to recruit only women who were resident at a place with a health facility for an in-depth interview. The interviews were recorded and transcribed into Microsoft word document. The transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 for thematic analyses.

Results:

The study found that quality of care was the main driver for traditional birth attendant delivery services. Poor attitude of midwives, maltreatment, and fear of caesarean section were barriers to skilled delivery. Community norms dictate that womanhood is linked to vaginal delivery and women who deliver through caesarean section do not receive the same level of respect. Traditional birth attendants were believed to be more experienced and understand the psychosocial needs of women during childbirth, unlike younger midwives. Furthermore, the inability of women to procure all items required for delivery at biomedical facilities emerged as push factors for traditional birth attendant delivery services. Preference for squatting position during childbirth and social support provided to mothers by traditional birth attendants are also an essential consideration for the use of their services.

Conclusion:

The study concludes that health managers should go beyond reducing financial and geographical access to improving quality of care and the birth experience of women. These are necessary to complement the efforts at increasing the availability of health facilities and free delivery services.

Keywords: childbirth, Ghana, quality of care, reasons, traditional birth attendants

Background

About 800 women are reported to die every day from pregnancy and childbirth-related causes.1 The majority (>90%) of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 The lifetime risk of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa is 1 in 38 women compared to 1 in 3700 in developed countries.1 A key component of the strategy to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality has been to increase rates of skilled birth attendance and facility-based childbirth.2 While global skilled birth attendance rates rose by 12% in LMICs over the past two decades, almost one-third of women in these regions still deliver without a skilled birth attendant.2

The importance of skilled attendance at birth lies in the fact that access to and use of maternity care facilities and skilled personnel, particularly skilled attendance at birth is often associated with substantial reductions in mortality and morbidity for the mother over home births.3–7 Despite this recognition, not all women seek skilled care during pregnancy or childbirth. Globally, several factors have been identified as barriers to skilled maternal healthcare access. Studies have shown that delivering in a health facility may be hampered by distance to facilities.8–10 Other studies indicate that structural factors, including lack of financial or economic resources, transportation, and delivery supplies, and lack of coordination of referrals between traditional birth attendants (TBAs) at the community level and facilities prevent women from using facility-based services11–15 Some studies also indicate that client’s negative perceptions of healthcare staff, including reports of unfriendliness at delivery serve as barriers to obtaining skilled care.11,15–17

Ghana has expanded its healthcare facilities to reduce geographical access to healthcare and also introduced the Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) strategy in both urban and rural areas to bring healthcare to the doorsteps of communities.18–20 Free maternal and delivery services were also introduced to break financial barriers to antenatal, skilled delivery, and postnatal services in 2008.21,22 Despite this, there is growing concern that many pregnant women still have unskilled delivery. For example, the most recent (2014) demographic and health survey showed that while the percentage of women making the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended four antenatal care visits is 87%, skilled attendance at birth is 74%.23 This implies that 26% of women delivered at home or used the services of traditional birth attendants. Again, a secondary data analysis conducted on the 2017 Ghana Maternal Health Survey showed that approximately 98.7% of maternal deaths completed less than four antenatal visits, and only 38.4% utilized skilled birth attendance during delivery.24 Unskilled delivery rates are higher in Northern Ghana.25 An earlier study showed that in the Northern part of Ghana about 39.1% of births occur at TBA facilities.26 This study was, therefore, conducted to identify the reasons for women’s preference for the service of TBAs when they live in communities with accessible health facilities and free service.

Methods and materials

Study design

This study adopted the phenomenology approach to qualitative enquiry.27 In phenomenological research, it is the participants’ perceptions, feelings, and lived experiences that are paramount and that are the object of study.28 This design was, therefore, deemed appropriate as the study aimed at documenting the lived experiences of women who delivered at TBA facility and the reason for their choice of facility.

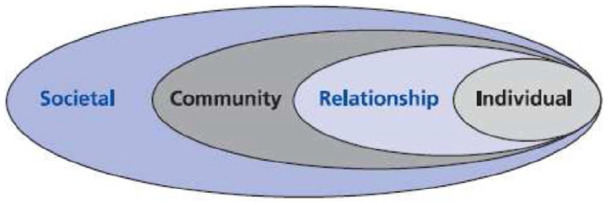

We adopted the social–ecological model. This model considers the complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors in affecting the phenomenon of interest.29 The structures at each of the constructs in the model overlap and illustrate how factors at one level influence factors at another level.

The individual constructs in the content of this study refer to the personal-level factors such as age, education, and income that influence individual health-seeking behaviour.30 The relationship which is the second level examines close relationships that may influence the likelihood of using TBAs for delivery. An individual’s closest social circle peers, partners, and family members influences their behaviour and contribute to their range of experience. The relationship factors also include previous experience with biomedical facilities or TBAs during childbirth. The third level (community) explores the settings, such as health facilities and neighbourhoods, in which social relationships occur and seeks to identify the characteristics of these settings that are associated with health-seeking behaviour31 during labour. The fourth and final level (societal) looks at the broad societal factors that help create a climate that drives people towards using the services of TBAs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Social–ecological model showing reasons for the utilization of the services of TBAs.

Study area

The study was conducted in Tolon District and Yendi Municipality in the Northern region of Ghana. The Tolon district is divided into three sub-districts for the delivery of healthcare. There are health centres in each of the sub-districts and CHPS compounds in communities in the district. Access to health facilities has been reported to be higher than the regional average.32 The Yendi municipality has a government hospital located in Yendi and four health centres located at Yendi, Bunbonayili, Ngani, and Adibo. The municipality also has four7 CHPS compounds at Sunson, Kuni, Kamshegu, Oseido, Montondo, Yimahegu, and Kpasanado. There is also a clinic at Malzeri and a private clinic at the Church of Christ premises in Yendi.33

The selection of the district was based on information gathered from the Regional Health Directorate and available literature. These two districts are noted for a high number of TBA deliveries in the region despite the availability of health facilities. In Tolon, it has been reported that each community has more than two TBAs.34 Yendi was also selected because of the number of TBAs in the district and had served as a district for the training of TBAs in the region in the past. As a result, the district has more than 30 TBAs across various communities.35

Study population and selection of participants

The study population were women who had live birth in the TBA facilities in one selected district and a municipality. Health workers in the selected districts were used to identify the TBAs who have high attendance based on their district report. Their facilities were visited and women who had childbirth with TBA pending their discharge were recruited for the study. An initial screening sheet was used to select eligible women. To be eligible, the person should be residing in a community with a health facility and should be gainfully employed with a monthly income of more than the minimum wage of GHȻ310.00 ($53.13). Financial access and travel distance have been reported as known barriers to skilled delivery. This strategy was, therefore, employed to exclude people who had to use TBA services because of non-availability of a health facility. Higher costs associated with seeking supervised maternity services have been noted as very critical to the uptake of care for many women in Ghana and other developing nations.5,36 Free maternal health service was introduced in Ghana as a pro-poor strategy to reduce the financial barrier to healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth. The free maternal health policy was implemented in Ghana in July 2008 under the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). The policy allows all pregnant women to have free registration with the NHIS after which they would be entitled to free services throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and three months postpartum.

Data collection tool and procedure

An in-depth interview (IDI) topic guide was used for the data collection. The topic guide was designed in English and translated into the local language (Dagbanli). The topic guide was designed according to the four constructs (individual, relationship, community, societal) in the social–ecological framework. For example, we asked questions about the reasons for utilizing the services of the TBA, the various actors in the decision-making process, and their views about the type of services provided by the TBA. For those who indicated they had previous experience with health facility delivery, we asked them to compare the services at the health facility with those rendered by the TBAs (see Supplementary file 1). These topic guides were pretested with five women who utilized the services of TBA in another suburb of Tamale. All the interviews were conducted by trained research assistants with previous experience in conducting qualitative interviews. We collected socio-demographic data such as age, education level, religion, and reproductive history at the end of the interview. The interviews for each day were transcribed before proceeding to conduct more interviews. The daily review and coding were useful in determining the point of saturation.37 Eligible women who refused to participate in the study were replaced. Four women who were eligible and recruited refused to participate for personal reasons. Interviews were conducted between March 2019 and June 2019. Interview sections lasted for 30–40 min.

Reflexivity and bracketing

Reflexivity relates to the degree of influence that the researcher brings to bear on the research either intentionally or unintentionally.38 Reflexivity enhances the quality of research and also boosts understanding of how the researcher’s own interest could affect the research process.39 Bracketing, on the contrary, refers to an investigator’s identification of vested interests, personal experience, cultural factors, and assumptions that could influence how he or she views the study’s data.40 In qualitative research adopting phenomenology, it is important for researchers to disclose their personal biases and measures that were put in place to improve rigour, trustworthiness, and credibility of the research findings. Several strategies were adopted in reflexivity and bracketing.

First, the research team did not have preconceived ideas and interest regarding the outcome of the study findings. The study was mainly informed by available literature that clearly shows that some women still have unskilled delivery despite the expansion of health facilities and introduction of free maternal healthcare policy. Furthermore, the research team and the research assistants were very open to study participants during data elicitation. There was no social or biological relationship between study participants and researchers. Although all the researchers have clinical training and practice, at the point of data collection and the research, none of the researchers was involved in clinical care.

In addition, research assistants with experience in conducting qualitative interviews were recruited and trained by the lead investigator. They were informed on the need to have a neutral mind and behaviour towards study participants during interviews or data collection. They were further told that any biased behaviour, preconceived beliefs, or values could affect the data that would be collected and that could further have a negative effect on the outcome of the study findings.

Recorded interviews were replayed to participants to make inputs and corrections. The interviews were transcribed verbatim. After the data collection and analysis, the findings were shared with some of the participants through a dissemination workshop. This enabled the participant to review and agree with the findings of the study as a form of member checking.41

In addition, a codebook was developed, reviewed, and accepted by the research team. Double coding of the data was done and compared. The coding trail was reviewed by an independent person for verification. Using the NVivo software, a coding comparison query showed a high level of agreement with a Kappa score of 0.92.42,43

Data analysis

All IDIs were recorded during the interview. The interviews were played to the interviewee after the interview for them to make the necessary corrections and addition. The recordings were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were reviewed by an independent person who listened to the recordings and compared the content with the transcriptions. Daily interviews were shared with other authors to review and provide feedback on the process. This iterative approach strengthened the data elicitation process. Interviews continued until data saturation was achieved.44 Hybrid inductive and deductive framework45 were used in developing the codebook, coding of the transcripts, and developing the themes. Conceptual dimensions of the interview guides guided the preliminary development of the codebook. This was then revised to include the emerging themes from the data. This codebook was discussed and accepted by all authors. The transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 12 for textual analysis. We used the case classification function in NVivo to identify each respondent and their attributes (socio-demographic and reproductive history). We first read through selected transcripts in NVivo and created nodes from the emerging issues in the data. Both free and free nodes were created during the coding until all the transcripts were coded. During coding, memos were written to key reflection from the data. The memos were linked to both the data sources and the nodes. Coded sections were regrouped into relevant categories and themes for presenting the results. Direct quotations were used, where appropriate, to support the themes. The main themes that depict reasons for patronizing the services of TBAs could basically be divided into biomedical health facility push factors and TBAs pull factors. These factors, which emerged from data, could be put into six sub-themes; good interpersonal relationship and practices by TBAs, post-delivery baby care and provision of special food by TBAs, requirements for labour in biomedical health facilities, preference for vaginal delivery and fear of caesarean section (C/S), perception about poor services in biomedical facilities and inexperienced midwives, and poor attitude of health workers during antenatal care (ANC) and facility delivery.

Ethical approval

The protocol for the study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Ghana Health Service (GHS-ERC 18/02/2019). All participants signed an informed consent form before participation.

Results

Background information of participants

Fourteen (45.2%) of the participants were between 20 and 30 years with majority of them (74.2%) having attended at least one ANC. Ten women (32.2%) have even delivered in a health facility (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and reproductive history of study participants.

| Background information | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <20 years | 8 | 25.8 |

| 20–30 years | 14 | 45.2 |

| >30 years | 9 | 29.0 |

| ANC attendance | ||

| Yes | 23 | 74.2 |

| No | 8 | 25.8 |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 6 | 19.3 |

| 2 | 7 | 22.6 |

| 3 | 8 | 25.8 |

| >3 | 10 | 32.3 |

| Previous hospital delivery | ||

| Yes | 10 | 32.2 |

| No | 21 | 67.8 |

ANC: antenatal care.

Good interpersonal relationship and practices by TBAs

Participants in this study revealed that they patronize the services of TBAs because of their good services and interpersonal relationship. This according to respondents in this study makes them feel confortable at their facilities. They are also able to discuss freely with TBAs their personal feelings and challenges. A participant shared her experience as follows:

I came here to deliver because the woman has a very good interpersonal relationship. When you come, she will welcome you and have time to listen to all your problems. So, we feel very comfortable discussing issues with her. (28 years, para 2)

Interviewees also indicated that TBAs allow women to assume any position of their choice during childbirth. So, individuals who opt to squat are allowed as it is believed this helps in pushing the baby out faster. They juxtaposed the squatting position with the lithotomy position at biomedical facilities which in their opinion gives discomfort. One interviewee revealed,

This woman treats us differently. When you come and you feel comfortable squatting to give birth, she will allow you, and her place is designed to suit that and this position helps to push the baby out faster but in the hospital, I was made to lie down and raise my leg and I could not breathe very well. (30 years, para 2)

Post-delivery baby care and provision of special food by TBAs

Participants in this study indicated one of the reasons for the use of the TBA during labour is the care of the baby after birth. In their opinion, the baby receives a special bath and massage, which is believed to make the baby strong. Moreover, some women patronize the services of TBA because they are served with some special food after delivery. This food in their view promotes lactation. The mothers are also fed on these hot meals until they are discharged from the facility. Two participants shared their experiences as follows:

When you deliver here [TBA facility] you are given special food until you are discharged. Unlike the hospital where nobody cares if you have eaten or not. This special soup is prepared for people who also deliver at home by our mother which helps bring breastmilk. (27 years, para 3)

The women (TBAs) are very good. I had my first baby here and she provided us with food and bathed the baby and applied good oil to massage the baby and my boy is very strong. He is the one playing over there. So that is why I have come here again. (29 years, para 2)

Respondents in this study also patronize TBAs because they provide them with some concoctions, which promote lactation and recovery as illustrated:

We can get some herbal preparations which are very good for our health, so it is one of the reasons why we come to her. After delivering you become strong instantly after taking what she gives to you.

Requirements for labour in biomedical health facilities

Furthermore, the inability of some women to acquire items requested for labour in biomedical facilities emerged as one of the reasons for unskilled delivery at TBAs. Participants believed that the list provided to prospective mothers during ANC deter women from going to biomedical health facilities during labour. In their opinion, a pregnant woman in labour who goes to the biomedical health facilities without all the items risk being scolded by midwives. Hence, women prefer to attend ANC at the biomedical health facilities and then go to TBA when labour starts. This concern was mostly raised by women who had previously delivered at a biomedical health facility. The following illustrates this point:

I attended ANC at the health facility where I was given a very long list of items to get for myself and baby and should come to the hospital with those items if I am coming to deliver. I cannot afford those items, so I came here and the woman can manage with what I have. But I am sure if I had gone to the hospital without those items, I will be shouted at. (32 years, para 3)

I delivered my first child at the hospital. When I got there in labour instead of the nurses attending to me they were busy checking the items I brought and started shouting at me why I didn’t bring this and that? But here the woman knows that some people cannot afford so whatever you bring the women will make do with it. (29 years, para 2)

Preference for vaginal delivery and fear of C/S

Respondents in this study also utilized the services of TBAs because of what they perceive as unnecessary operations in the hospital. To some of them, when you go to the hospital and there is any delay in labour, C/S is performed. Unlike the TBAs where you may be given some herbal preparations to facilitate vaginal delivery. This was necessary because in their view, motherhood is linked to vaginal delivery and women take pride in their ability to give birth through the vagina. Interviewees were also of the view that babies delivered through the vagina are stronger and more intelligent than those delivered through C/S. The following quotes illustrate these points:

My friend went to the hospital and experience some delay in the baby coming out [being delivered] and they operate on her. She was unhappy so I was afraid that may happen to me too. The woman gave me something to drink and shortly the baby came out. (25 years, para 1)

All women prefer vaginal delivery because that makes you a woman and a mother. If they operate you to remove the baby people do not respect you. Children born through the vagina are also stronger and intelligent. (31 years, para 2)

Perception about poor services in biomedical facilities and inexperienced midwives

Interviewees were unanimous of the poor quality of service rendered at biomedical health facilities. Quick service and good medical attention were mentioned as key quality indicators in this study. Generally, respondents were of the opinion that there were always delays at biomedical health facilities. Therefore, they prefer to utilize the services of TBAs who provide their clients better and quick service. A participant shared her experience as follows:

Usually these days when you go to the health centre or the hospital, you spend a lot of time waiting and when it is even time for you to see the doctor or nurses, their services do not meet our expectation. So, for me, I prefer to use TBA. They will listen to you very well and provide you with the best of care. (28 years para 2)

Interviewees also indicated that disrespect at biomedical health facilities is one of the reasons for patronizing the TBAs. To them, TBAs were experienced women, and respect the dignity of womanhood and, therefore, treat women with love and compassion. Interviewees also characterized TBAs as mothers who have gone through labour and, therefore, have a better understanding of the process. In their view, some midwives in biomedical health facilities have not experienced pregnancy and childbirth and, therefore, are less responsive to the psychosocial needs of women. The following quotes support these claims by participants:

I often hear that when you go to the hospital the nurse will be rude towards you and shout at you. So, I decided to come to this woman whom I know she has children and will know what it takes to deliver. (26 years, para 1)

TBAs have children and have experienced the process of giving birth better than some of the nurses in the hospital. Some nurses especially the young ones have never given birth and therefore do not appreciate the pain and suffering women go through. (34 years, para 3)

Poor attitude of health workers during ANC and facility delivery

Poor quality of services at the health facilities due to non-availability of midwives, negative experiences with midwives during ANC visits emerged as one of the reasons for women delivering at TBA. Interviews with postnatal women revealed that they were badly treated or had to wait for a longer duration in the hospital before receiving care. Hence, they did not want that to happen to them during labour as that could lead to the death of the baby which they so much desired to have:

. . . If you check my card, you will find that I have attended ANC at [health facility name withheld] but the delays there were just too much. So, I was afraid that may happen to me during childbirth and that can affect my baby or result in the death of my baby. I have been looking for this pregnancy for long. (34 years, para 1)

Also, previous experience of maltreatment during labour was mentioned as a reason for TBA delivery. In the view of such respondents, health workers in labour wards have now become so insensitive to the concerns of women in labour. One shared her experience where she was in distress but was ignored by the midwife on duty. This according to her resulted in stillbirth after an initial ultrasound had shown that the baby was alive:

This is my second delivery. On my first birth, I went to the hospital when I started feeling pain. So, I got to the hospital and was there for some time and was asked to go for a scan which I did and they told me the baby was alive. I spend the whole night in the hospital and when I am in pain and I call the nurse, she will shout at me that it is not time. Until the baby came out and they told me the baby was dead. Since that time, my friend advised me to come to this woman because she is more experienced than the young nurses in the hospital these days. (30 years, para 2)

Another woman narrated how she was neglected during labour while the nurses were busy chatting with people on their phones. She, therefore, called on health managers to ban the use of mobile phones by health workers on duty:

In my case, I went to the hospital and the nurse told me it was too early for me to deliver after examining me. They left me there in very serious pain whilst they were busy chatting and one of them was using WhatsApp. The use of phone should be ban, it has come to increase the neglect that patients receive. The young nurses are always busy chatting with boyfriends whilst on duty. (33 years, para 2)

Discussion

The poor attitude of midwives emerged as a push factor for facility delivery while encouraging the patronage of TBAs. This finding brings to bear that even though the challenges of accessibility are being addressed by providing more health facilities through the scale-up of the CHPS strategy, there are still significant issues relating to the negative attitude of health workers. It is important to note that the attention given to women by TBAs and quality of care is a motivation for many women to access their services. Quality of care has been defined as the difference between how medical care can optimally be delivered and how it is delivered.46 Several studies have demonstrated the role of quality care in producing enhanced maternal health outcomes.46–48 To this end, evidence from diverse settings has suggested that increasing facility delivery may not reduce mortality if the quality of care is poor.49–51 For instance, a 2013 analysis of WHO multi-country survey data suggest that coverage with life-saving interventions may be insufficient to reduce maternal deaths without overall improvements in the quality of maternal healthcare.52 There is, therefore, the need to put in place measures to improve the quality of care and birth experiences of women. Customer care can also be incorporated into the training of health workers.

Participants in this study were of the view that TBAs have an in-depth understanding of labour and have a better sense of urgency to act and willing to support mothers. These attributes led to expectant mothers’ preference for their service. In contrast, services at hospitals were seen as poor with health workers treating the expectant mother with discontent. These negative attitudes prevented women from utilizing skilled delivery. Similarly, a study in Northern Ghana has shown that women refused to patronize facility-based delivery because of poor quality and maltreatment during labour.34 The findings of this study underscore the need for nurses to change their attitude towards clients that seek healthcare.

The study found squatting position as one of the reasons for the use of TBA facilities. Another reason cited for delivery at TBA facilities is the use of herbs, which is believed to be effective and facilitate the labour process. As found in some studies, women’s preference for TBAs during pregnancy and labour, compared to the healthcare facilities, was due to the use of herbal medications, which was preferred to the drugs and vaccines administered at the ANC clinics.53 In light of these, health education offered to women during ANC visits should highlight the necessity for the continuum of care that includes skilled attendance at birth and postnatal care. Again studies have reported that even women who attend ANC still go to deliver at TBA facilities.54 As more than 65% of maternal deaths occur during delivery, the importance of having a skilled attendant in a facility with adequate healthcare services during the time of birth cannot be overemphasized.55 Furthermore, orthodox healthcare providers are guided by procedures that may be at variance with the cultural inclinations of pregnant women.56–58 It is, therefore, critical for health facilities to identify some of the good practices of the TBAs and incorporate them into biomedical healthcare services. Collaboration between TBAs and health workers in biomedical facilities can provide an opportunity for the training of TBAs on danger signs during labour and encouraging them to refer such cases to avert complications.

Another barrier to utilization of skilled delivery was the fear of C/S section and perceived belief of the high incidence of C/S. This fear is related to community beliefs that motherhood was generally related to vagina delivery. Hence women who give birth through C/S did not receive the same recognition as those who deliver through the vagina. However, since the TBAs did not have expertise in performing C/S, respondents were of the view that using their outlet was an assurance that one could avoid C/S outcome. An earlier study showed Ghanaian women’s preference for vaginal delivery,59 but our study highlights the reasons for their preference. An earlier study has shown that women generally prefer vaginal delivery with about 11.6% of C/S deliveries refusing this mode of delivery in developing countries.60 Low preference for C/S has been reported across the world in a systematic and meta-analysis of observational studies.61 Per the WHO standards, C/S rates are generally reported to be higher than the expected 5%–15% of all births.62 C/S rates in Ghana have been reported to vary between 3.3 in rural poor women to 10.8 in urban richer women. A study conducted at the University of Cape Coast Teaching Hospital found a C/S rate of 26.9%.63 Though there is inconsistency in the rate of C/S, it is clear the rates are relatively high. Moving forward there is, therefore, the need to do case reviews of C/S conducted in different hospitals to inform policy.

Limitations of the study

Even though this study provides useful insights and reasons for the continuous patronage of the services of the TBAs, it is important to note a few limitations. One weakness in qualitative studies is the inability to generalize the findings.27 Nonetheless, we employed maximum variation sampling technique involving women from different communities and TBAs operating at different locations to strengthen the findings of the study while increasing the credibility, dependability, and trustworthiness64 of the evidence from the study.

In addition, some of the interviews were conducted in the local languages and translated into English, hence some words could have lost their original meanings as a result of the translation. To minimize the effects of possible distortions due to translations, each translation was done by two people and the research team reviewed the translations from the local languages. Nevertheless, given the limitations of such a procedure, little weight was placed on the specific wording or phrasing of responses but on the overarching themes from the data.

Conclusion

The study concludes that health managers should go beyond reducing financial and geographical access to improving the quality of care and birth experience of women. Financial and geographical access is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee skilled delivery. Quality of care is necessary to complement the efforts at increasing the availability of health facilities and free delivery services. Accepting harmless social practices during labour will improve trust and cater for community’s worldview about childbirth.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211002483 for Reasons for the utilization of the services of traditional birth attendants during childbirth: A qualitative study in Northern Ghana by Philip Teg-Nefaah Tabong, Joseph Maaminu Kyilleh and William Wilberforce Amoah in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants for accepting to be part of the study.

Footnotes

Author contributions: P.T.-N.T. was involved in the conceptualization, methodology, data collection, formal analysis, and writing – original draft of the article. J.M.K. also was involved in the conceptualization of the article. J.M.K. and W.W.A. were involved in the methodology, data collection, writing – review and editing of the article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Philip Teg-Nefaah Tabong  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9445-1643

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9445-1643

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, et al. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNIFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations population Division. World Health Organization, 2014, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112682/2/9789241507226_eng.pdf?ua=1

- 2. World Health Organization. Factsheet Proportion of births attended by a skilled health worker 2008 updates Factsheet. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cham M, Sundby J, Vangen S. Maternal mortality in the rural Gambia, a qualitative study on access to emergency obstetric care. Reprod Health 2005; 2: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith KV, Sulzbach S. Community-based health insurance and access to maternal health services: evidence from three West African countries. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66(12): 2460–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria—looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009; 9: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abor PA, Abekah-Nkrumah G, Sakyi K, et al. The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in Ghana. Int J Soc Econ 2011; 38: 628–648, http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-79959199017&partnerID=40&md5=1661fa3d20926b82c8afcc19ab47dd3e [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsawe M, Susuman A. Determinants of access to and use of maternal health care services in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a quantitative and qualitative investigation. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7(1): 723, http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/7/723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moyer CA, McLaren ZM, Adanu RM, et al. Understanding the relationship between access to care and facility-based delivery through analysis of the 2008 Ghana Demographic Health Survey. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2013; 122(3): 224–229, 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yanagisawa S, Oum S, Wakai S, et al. Determinants of antenatal care, institutional delivery and skilled birth attendant utilization in Samre Saharti District, Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Preg Childbirth 2013; 7(1): 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ganle JK, Parker M, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Inequities in accessibility to and utilisation of maternal health services in Ghana after user-fee exemption: a descriptive study. Int J Equity Health 2014; 13(1): 89, http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/13/1/89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mills S, Bertrand JT. Use of health professionals for obstetric care in northern Ghana. Stud Fam Plann 2005; 36(1): 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seljeskog L, Sundby J, Chimango J. Factors influencing women’s choice of place of delivery in rural Malawi—an explorative study. Afr J Reprod Health 2006; 10(3): 66–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. ten Hoope-Bender P, Liljestrand J, MacDonagh S. Human resources and access to maternal health care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006; 94(3): 226–233, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16904675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mills S, Williams JE, Adjuik M, et al. Use of health professionals for delivery following the availability of free obstetric care in Northern Ghana. Matern Child Health J 2008; 12(4): 509–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okafor CB, Rizzuto RR. Women’s and health-care providers’ views of maternal practices and services in rural Nigeria. Stud Fam Plann 2015; 25(6 Pt. 1): 353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Griffiths P, Stephenson R. Understanding users’ perspectives of barriers to maternal health care use in Maharashtra, India. J Biosoc Sci 2001; 33(3): 339–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seljeskog L, Sundby J, Chimango J. Factors influencing women’s choice of place of delivery in rural Malawi: an explorative study. Afr J Reprod Health 2006; 10(3): 66–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nyonator F, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, et al. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy Plan 2005; 20(1): 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA, Nyonator FK, et al. The Ghana essential health interventions program: a plausibility trial of the impact of health systems strengthening on maternal & child survival. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13(Suppl 2): S3, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3668206&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract%5Cnhttp://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/13/S2/S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adongo PB, Phillips JF, Aikins M, et al. Does the design and implementation of proven innovations for delivering basic primary health care services in rural communities fit the urban setting: the case of Ghana’s Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS). Heal Res policy Syst 2014; 12: 16, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3994228&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ministry of Health. Ghana MDG acceleration framework (MAF): 2015 strategic and operational plan. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anafi P, Mprah WK, Jackson AM, et al. Implementation of fee-free maternal health-care policy in Ghana: perspectives of users of antenatal and delivery care services from public health-care facilities in Accra. Int Q Community Health Educ 2018; 38: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. GSS/GHS/Macro International. Ghana demographic and health survey 2014, Accra, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR224/SR224.pdf

- 24. Sumankuuro J, Wulifan JK, Angko W, et al. Predictors of maternal mortality in Ghana: evidence from the 2017 GMHS verbal autopsy data. Int J Health Plann Manage 2020; 35: 1512–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. GSS/GHS/ICF. Ghana 2017 maternal health survey: key findings. Rockville, MD, 2018, https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR251/SR251.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. GSS. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Accra, 2011, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2046#:~:text=The%20Multiple%20Indicator%20Cluster%20Survey,situation%20of%20children%20and%20women

- 27. Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health service. 4th ed. London: Open University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wertz FJ. Phenomenological research methods for counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol 2005; 52(2): 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dahlberg L, Krug E. Violence-a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. (eds) World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002, pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol 1986; 22: 723–742. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bronfenbrenner V. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tolon District Assembly. 2016 Composite Budget for Tolon District. Tolon, Ghana: Tolon District Assembly, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yendi Municipal Assemble. 2019 composite budget for Yendi municipality. Yendi, Ghana: Yendi Municipal Assemble, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Allou LA. Factors influencing the utilization of TBA services by women in the Tolon district of the northern region of Ghana. Sci African 2018; 1: e00010. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shamsu-Deen Z. Assessment of the contribution of traditional birth attendants in maternal and child health care delivery in the Yendi district of Ghana. Dev Ctry Stud 2013; 3: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moyer CA, Adongo PB, Aborigo RA, et al. ‘They treat you like you are not a human being’: Maltreatment during labour and delivery in rural northern Ghana. Midwifery 2014; 30(2): 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Creswell WJ, Creswell JD. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-publication Data Names, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res 2015; 15: 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dodgson JE. Reflexivity in qualitative research. J Hum Lact 2019; 35: 220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fischer CT. Bracketing in qualitative research: conceptual and practical matters. Psychother Res 2009; 19: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, et al. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation. Qual Health Res 2016; 26(13): 1802–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tabong PT-N, Maya ET, Adda-Balinia T, Kusi-Appouh D, et al. Acceptability and stakeholders perspectives on feasibility of using trained psychologists and health workers to deliver school-based sexual and reproductive health services to adolescents in urban Accra, Ghana. Reprod Health 2018; 15(1): 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tabong PT-N, Bawontuo V, Dumah DN, Kyilleh JM, et al. Premorbid risk perception, lifestyle, adherence and coping strategies of people with diabetes mellitus: a phenomenological study in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE 2018; 13(6): e0198915, 10.1371/journal.pone.0198915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elo S, Kaariainen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014; 4(1): 1–10, http://sgo.sagepub.com/lookup/doi/10.1177/2158244014522633 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006; 5(1): 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salinas AM, Coria I, Reyes H, et al. Effect of quality of care on preventable perinatal mortality. Int J Qual Health Care 1997; 9(2): 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kendall T, Langer A. Critical maternal health knowledge gaps in low-and middle-income countries for the post-2015 era. Reprod Health 2015; 12(1): 55, http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content/12/1/55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tripathi V, Stanton C, Strobino D, et al. Development and validation of an index to measure the quality of facility-based labor and delivery care processes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(6): e0129491, http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barber SL, Gertler PJ. Empowering women to obtain high quality care: evidence from an evaluation of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme. Health Policy Plan 2009; 24(1): 18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, et al. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet 2010; 375(9730): 2009–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India’s conditional cash transfer programme (the JSY) to promote institutional birth: is there an association between institutional birth proportion and maternal mortality. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(6): e67452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Vogel J, et al. Moving beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the {WHO} Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2013; 381(9879): 1747–1755, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673613606868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2014; 128: 110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ribeiro Sarmento D. Traditional Birth Attendance (TBA) in a health system: what are the roles, benefits and challenges: a case study of incorporated TBA in Timor-Leste. Asia Pac Fam Med 2014; 13(1): 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adegoke AA, van den Broek N. Skilled birth attendance-lessons learnt. BJOG 2009; 116(Suppl. 1): 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rööst M, Johnsdotter S, Liljestrand J, et al. A qualitative study of conceptions and attitudes regarding maternal mortality among traditional birth attendants in rural Guatemala. BJOG 2004; 111(12): 1372–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Berry NS. Kaqchikel midwives, home births, and emergency obstetric referrals in Guatemala: contextualizing the choice to stay at home. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62(8): 1958–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deshpande NA, Oxford CM. Management of pregnant patients who refuse medically indicated cesarean delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2012; 5(3–4): e144–e150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Danso K, Schwandt H, Turpin C, et al. Preference of Ghanaian women for vaginal or caesarean delivery postpartum. Ghana Med J 2009; 43(1): 29–33, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19652752%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC2709173 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chigbu CO, Iloabachie GC. The burden of caesarean section refusal in a developing country setting. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 114(10): 1261–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mazzoni A, Althabe F, Liu NH, et al. Women’s preference for caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BJOG 2011; 118(4): 391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. WHO. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Prah J, Kudom A, Afrifa A, et al. Caesarean section in a primary health facility in Ghana: clinical indications and feto-maternal outcomes. J Public Health Africa 2017; 8(2): 155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 2017; 16: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455065211002483 for Reasons for the utilization of the services of traditional birth attendants during childbirth: A qualitative study in Northern Ghana by Philip Teg-Nefaah Tabong, Joseph Maaminu Kyilleh and William Wilberforce Amoah in Women’s Health